Archived information

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

Archived

Synthesis Report – Ethiopia and Ghana Country Program Cluster Evaluation

Fiscal year 2008/09 to 2013/14

May 2015

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the independent evaluation team from Goss Gilroy Inc. for their work in conducting this evaluation – namely, Hubert Paulmer, Louise Mailloux, Steve Mendelsohn, Tasha Truant, Lindsay Renaud, Bruce Goodman and Neal McMillan – and thank them all for their hard work, diligence and professionalism in undertaking this challenging assignment. We are also very grateful for the contributions made by colleagues based in Ethiopia, Amdissa Teshome and Melete Gebregiorgis, and those based in Ghana, Vida Ofori and Frédéric Kouwoaya.

The evaluation team particularly appreciated the time afforded to the evaluators by the various stakeholders interviewed or consulted over the course of the evaluation. This includes the individuals from government, international organizations, civil society organizations, the private sector, and other development partners, who graciously made themselves available for interviews in Canada, Ethiopia and Ghana.

From the Development Evaluation Division, Vivek Prakash managed the first half of the evaluation process, succeeded by Deborah McWhinney. Michelle Guertin and then Tara Carney, Evaluation Team Leaders, were responsible for overall supervision.

James Melanson

Head of Development Evaluation

Table of Contents

List of Acronyms and Abbreviations

- ADLI

- Agricultural Development-led Industrialization

- AFD

- Agence Française de Développement (French Development Agency)

- AGP

- Agricultural Growth Program

- ATA

- Agricultural Transformation Agency

- BSG FSEG

- Benishangul-Gumuz Food Security and Economic Growth Project

- CDPF

- Country Development Program Framework

- CFTC

- Canadian Feed the Children

- CHANGE

- Climate Change Adaptation in Northern Ghana Enhanced

- CHF

- Canadian Hunger Foundation

- CIDA

- Canadian International Development Agency

- CDPF

- Country Development Program Framework

- CIFS

- Community-driven Initiatives for Food Security

- CIFSRF

- Canadian International Food Security Research Fund

- CMAM

- Centres for the Management of Acute Malnutrition

- CSB

- Corn-soya blend

- CORE

- Core funding, DFATD

- CSIR

- Council for Scientific and Industrial Research

- CSO

- Civil Society Organizations

- DAC

- Development Assistance Committee (of the OECD)

- DDF

- District Development Facility

- DFATD

- Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development

- DIRE

- Directive funding, DFATD

- DWAP

- District-wide Assistance Transition Project

- ECCRING

- Expanding Climate Change Resilience in Northern Ghana

- ECCO

- Ethiopia Canada Co-operation Office

- EPA

- Environmental Protection Agency

- ESSP

- Ethiopia Strategy Support Program

- FASDEP

- Food and Agriculture Sector Development Policy

- FBO

- Farmer-based Organization

- FOAT

- Functional Organizational Assessment Tool

- FSAG

- Food Security and Agricultural Growth

- FSAS

- Food Security Advisory Services

- FSEF

- Food Security and Environment Facility

- FSP

- Food Security Program

- GAFSP

- Global Agriculture and Food Security Program

- GAM

- Global Acute Malnutrition

- GDI

- Gender Development Index

- GEMP

- Ghana Environmental Management Project

- GGPRSP

- Ghana Growth and Poverty Reduction Support Program

- GHS

- Ghana Health Services

- GoE

- Government of Ethiopia

- GoG

- Government of Ghana

- GNI

- Gross National Income

- GPB

- Geographic Program Branch

- GPRS

- Growth and Poverty Reduction Strategy

- GSGDA

- Ghana Shared Growth and Development Agenda

- GTP

- Growth and Transformation Plan

- HDI

- Human Development Index

- IDRC

- International Development Research Centre

- IFPRI

- International Food Policy Research Institute

- IMRT

- Investment Monitoring and Reporting Tool

- INGO

- International Non-governmental Organization

- IPMS

- Improving Productivity and Market Success

- KFM

- Partnerships for Development Innovation Branch

- KfW

- Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau (Reconstruction Credit Institute)

- LAP II

- Land Administration Project, Phase II

- LIVES

- Livestock and Irrigation Value Chains for Ethiopian Smallholders

- MBSIL

- Market-based Solutions for Improved Livelihoods.

- MDG

- Millennium Development Goal

- MERET

- Managing Environmental Resources to Enable Transition to more Sustainable Livelihoods

- MESTI

- Ministry of Environment Science and Technology and Innovation, Ethiopia

- METASIP

- Medium-term Agriculture Sector Investment Plan

- MFM

- Global Issues and Development Branch

- MGP

- Multilateral and Global Program Branch

- MLGRD

- Ministry of Local Government and Rural Development, Ghana

- MMDA

- Metropolitan, Municipal and District Assemblies, Ghana

- MoA

- Ministry of Agriculture, Ethiopia

- MoFA

- Ministry of Food and Agriculture, Ghana

- MoGCSP

- Ministry of Gender, Children and Social Protection, Ghana

- MoWAC

- Ministry of Women and Children Affairs, Ghana

- MSR

- Management Summary Report

- MTA

- Mid-term Assessment

- NCCPF

- National Climate Change Policy Framework, Ghana

- NDAP

- National Decentralization Action Plan, Ghana

- NDPC

- National Development Planning Commission

- NGO

- Non-governmental Organization

- OECD

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

- P4P

- Purchase for Progress

- PASDEP

- Plan for Accelerated and Sustained Development to End Poverty

- PBA

- Program-based Approach

- PHMIL

- Post-Harvest Management to Improve Livelihoods

- PIF

- Policy and Investment Framework

- PMF

- Performance Measurement Framework

- PRRO

- Protracted Relief and Recovery Operations

- PSNP

- Productive Safety Net Program

- PSU

- Program Support Unit

- PTL

- Project Team Leader

- PWCB

- Partnerships with Canadians Branch

- RBM

- Results Based Management

- RCBP

- Rural Capacity Building Project

- REACH

- Renewed Efforts against Child Hunger

- RELC

- Research-Extension Linkage Committees

- RESP

- Responsive funding, DFATD

- SADA

- Savannah Accelerated Development Authority

- SBS

- Sector budget support

- SEG

- Sustainable Economic Growth

- SFASDEP

- Support to FASDEP

- SIGEP

- Strategic Initiatives for Gender Equality Project

- SLMP

- Sustainable Land Management Program

- SNSF

- Safety Net Support Facility

- SUN

- Scaling Up Nutrition

- SWHISA

- Sustainable Water Harvesting and Institutional Strengthening in Amhara

- UN

- United Nations

- UNDP

- United Nations Development Program

- UNICEF

- United Nations Children’s Fund

- USAID

- United States Agency for International Development

- WIAD

- Women in Agriculture Development Directorate

- WASH

- Water, Sanitation and Hygiene

- WFP

- World Food Program

- WGM

- Sub-Saharan Africa Branch

Executive Summary

Introduction

The Ethiopia and Ghana Country Program Cluster Evaluation was conducted between December 2013 and December 2014. It assessed the performance of the Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development (DFATD) in providing development assistance to Ethiopia and Ghana during fiscal years 2008/09 - 2013/2014, with a particular focus on food security.

The objective of the evaluation was to assess the performance of the Ethiopia and Ghana Country Programs against the standard evaluation criteria of relevance, effectiveness, efficiency, and sustainability, as well as cross-cutting themes of gender equality, environmental sustainability and governance. The implementation of DFATD’s food security strategy in the two countries was also examined.

Approach and Methodology

The evaluation assessed the extent to which the Country Programs (including initiatives from the three DFATD Branches) attained planned results as specified in the goals and objectives and/or stated outcomes in the respective program and project logic models and performance measurement frameworks (PMFs).

Mixed methods were used, including document and literature review (245), key informant interviews (212), focus groups and case studies or site visits (9 districts in Ethiopia and 6 districts in Ghana). This approach allowed the team to gather and triangulate multiple lines of evidence. The evaluation sampled 40 projects: 20 in the Ethiopia Program ($344.32 million representing 54.3% of total disbursements, and 82.3% of those for food security); and 20 in the Ghana Program ($223.87 million representing 44.8% of total disbursements and 92.5% of those for food security).

Ethiopia - Findings and Conclusions

Relevance

Overall, the Ethiopia Program was relevant and well aligned to Government of Ethiopia (GoE) and DFATD priorities and commitments. The DFATD Country Program supported GoE flagship programs directly targeted at reducing hunger and extreme poverty, while others focused on improved agricultural productivity and practices.

Canada has met G8 commitments in Ethiopia through the L’Aquila Food Security Initiative, New Alliance for Food Security and Nutrition, Scaling-Up Nutrition, Food Assistance Convention and the Muskoka Initiative, and more recent projects have been consistent with DFATD’s Food Security Strategy.

Effectiveness

Approximately half of the funding ($176 million) during the evaluation period supported one of the GoE’s flagship programs, the Productive Safety Net Program (PSNP). Independent studies have confirmed a consistent and significant decrease in the food gap in the targeted PSNP districts and that approximately 2.5 million people were able to graduate out of PNSP since 2005. Canada made a significant contribution to these results.

Canada supported the GoE’s focus on improving nutrition that led to improved nutritional status in 100 food insecure districts, and increased school enrolment, with the provision of meals and take-home rations for girl students.

The Program also supported initiatives that contributed to increased productivity and incomes in sustainable agricultural development, including the rehabilitation of over one million hectares of degraded land, training of 58,000 farmers in new methods (43,000 focused on improved crop production, 12,000 on livestock and 3,000 on conservation), the creation of 1,500 farmer innovation groups and 263 primary cooperatives, and initiation of 125 irrigation schemes.

Funding intended to strengthen Ethiopia’s agricultural research capacity was provided, but outcomes were difficult to discern at the time of the evaluation.

The Ethiopia Program has been active and effective in policy dialogue through the Development Action Group (high level), donor coordination groups and project level working groups. Canada currently chairs the Rural Economic Development and Food Security Working Group and is active in the PSNP donor coordination committee and the Agricultural Growth Program (AGP) working group among others.

Sustainability

Donors have been committed to supporting the national flagship programs in Ethiopia that feature multi-donor pooled funding with strong national government leadership. The GoE, in turn, has committed to donor-supported projects that are consistent with its national planning priorities.

In addition to alignment with government priorities, sustainability of the initiatives supported by the Ethiopia Program has also been enhanced by extensive support for capacity building targeting not only service delivery agents, but also end users, including farmers, Development Officers of the Ministry of Agriculture (MoA), and local government officials. Success was, however, diminished to some extent by the high turnover rate of government staff (a common phenomenon in many developing countries).

Cross-cutting Themes

Canada is seen as a strong advocate for gender equality among donors, particularly evident in the coordination/working groups of donor-supported GoE programs. Projects sampled from the Ethiopia Program showed proactive integration of gender equality in planning, however in some cases, the results achieved were mixed.

Environmental sustainability was well integrated into design and implementation in many of the sampled projects, including the integration of improved land and water management. A significant component of the large Productive Safety Net Program incorporated environmental sustainability – for example, rehabilitation of degraded lands, increased vegetative cover, embankments, reduced soil erosion and improved water management.

Governance was not an explicit aspect of the projects that were sampled in Ethiopia. There was little evidence that the Ethiopia Program had either assessed its projects against governance indicators or planned specific interventions to improve governance, with the exception of capacity building support. It should be recognised however that governance was not established as a cross-cutting theme until later in the evaluation period.

The two GoE flagship programs – PSNP and AGP – have extensive components that deal with improved program governance, including improved systems and structures for assessing community needs and responding to these needs, budgetary management, audit structures, and the extensive use of working groups at the national, regional and woreda levels.

Efficiency

The evaluation found the efficiency of the Ethiopia Program to be satisfactory. On average, it cost $2.65 million (including salary, program support unit (PSU) and Operating and Management funds) to disburse and manage $81 million annually. This was equivalent to 3.3% of the yearly disbursement of bilateral funds to the country. In should be kept in mind, however, that many of the bilateral projects are implemented by multilateral organizations, such as UNICEF, World Food Programme and the World Bank. These organizations also have administrative charges that are incorporated into project costs, which were not explicitly included in the calculation above.

Management Factors

The evaluation found satisfactory use of performance management frameworks, monitoring and reporting, and risk management in the Ethiopia Program. However, the program logic model and performance measurement frameworks for the Country Development Program Framework (CDPF) had not been updated since the current Country Program cycle began, although the Program has changed significantly.

There was a lack of consistency in reporting among DFATD-funded projects. Among the three branches, only certain bilateral projects had Management Summary Reports (MSRs) and they were not always completed consistently. While this is not specific to the Ethiopia Program, the current MSR format focuses to a great extent on cross cutting themes with limited attention paid to a review of progress towards expected outcomes in comparison with baselines or targets identified in the original or amended approval documents. This impedes the Programs’ ability to monitor and report effectively on progress.

Adherence to Paris declaration principles is reflected in the approach that DFATD has taken to complement the GoE’s strong sense of ownership over its policies, strategies and national flagship programs, and individual projects. Projects were well aligned with both national and local priorities and supportive of the use of local systems.

The evaluation team found evidence that coordination and coherence among the three DFATD Branches engaged in development in Ethiopia was informal but relatively good.

Conclusions

- The Ethiopia Program was relevant to and aligned with the GoE’s priorities and policies, as well as with international commitments and Canadian priorities.

- The Program was highly satisfactory in terms of results achieved. It supported key GoE flagship programs, one of which has been cited by the World Bank as a model for a social safety net program. The Program contributed to improved production practices, better soil and water conservation practices, sustainable land and water management, increased income for farmers, increased food security, decreased food gap, decreases in asset sales, improved nutrition and increased resilience. There is evidence that Ethiopia was not affected as much as other countries in the region during the 2011 Horn of Africa drought.

- The Ethiopia Program strengthened capacities at various levels of government (including MoA personnel) and communities. It has been effective in policy dialogue through donor working groups of the national flagship programs. An appropriate enabling environment, including community and government structures, has been put in place for the implementation of the two national flagship programs reviewed in this evaluation.

- Several projects have progressed or taken appropriate steps to ensure sustainability. Capacity building is intrinsic to almost all projects, and local systems were often used, especially for the national flagship programs (PSNP and AGP). One of the key challenges to sustainability has been to get the government to make budget provisions for operational costs. Government commitments to national Programs represented a positive step, although given Ethiopia’s economic status, several cycles of donor support may be required, especially for the multi-donor flagship programs.

- Good progress was made in gender equality, and environmental sustainability was strongly integrated into a number of projects. Governance was a more recent addition as a cross-cutting theme and, hence, several projects have not addressed it explicitly.

- In general, projects were efficient. They started on time and stayed within budget. However, the efficiency of projects was affected by delays in approval and start-up, and consequently shortened timeframes for implementation.

- At the level of individual projects, performance management frameworks exist and were monitored and reported on regularly. At the Program level, although the CDPF was prepared for five years, the logic model and PMF underwent several rounds of revisions and were not always aligned. Overall monitoring and reporting at the Program level was weak, and corrective action is recommended.

- The GoE had a strong sense of ownership of its policies and strategies and developed national flagship programs. The Ethiopia Program used local systems, not only in flagship programs, but also for other smaller and focused projects.

- Interaction among the three DFATD branches programming in Ethiopia increased over time. However, no formal coordination mechanism existed, even in a large and decentralized Program such as Ethiopia’s.

- There was a balanced approach to agricultural development through three main flagship programs, which included food security and nutrition, agricultural growth and development, research, and sustainable land and water management. By supporting flagship programs, Canada supported all aspects of the agriculture sector in addition to creating value at different levels of government and in the community.

Lessons Learned

- Working through large government flagship programs in a program-based approach works best when technical assistance is provided to support program implementation. In Ethiopia, having a strong local team of advisors in agriculture, food security, gender and capacity building was a crucial factor for successful program delivery and management, as well as capacity building.

- Programming through multi-donor pooled funds helped expand the reach of the Program to a larger number of beneficiaries. It also leveraged Canadian policy dialogue through donor coordination and donor working groups.

- The PSNP is a well-designed and strongly performing social safety net system that could be a model for other countries, as is the system of donor coordination that it employs. The PSNP operationalizes the Paris Declaration principles effectively — government ownership, donor harmonization and use of local systems.

- The experience in Ethiopia indicates that individual projects that are not fully supported by the GoE and which are not well integrated into the government budgeting and planning systems have a reduced chance of sustainability and are less likely to be scaled up.

- The flagship programs in Ethiopia underline the importance of community involvement and bottom-up planning of major national programs as a way of ensuring that implementation leads to results.

Ghana - Findings and Conclusions

Relevance

Canadian programming has been highly relevant and congruent with the development priorities of the Government of Ghana as described in their Growth and Poverty Reduction Strategy and the Ghana Shared Growth and Development Agenda, of which agriculture is a key driver. The Ghana Program’s initiatives were also designed to support the National Decentralization Action Plan/National Decentralization Policy Framework.

The Ghana Program contributed to budget support at three levels of government (national, regional, district), thereby allowing DFATD to gain an overall perspective of the strengths and weaknesses in key national policies, plans and systems down to the district level.

Canada’s focus on Ghana’s three northern regions has addressed the higher levels of poverty (63% in the north compared to 20% in the south), food insecurity and malnutrition that exist there.

Investments in food security were already a part of Canadian development programming in Ghana prior to the launch of the Food Security Strategy in 2009 and helped Canada to meet its global commitments (L’Aquila Food Security Initiative and the New Alliance) on food security and agricultural spending in developing countries. Canadian support for sustainable agriculture development and nutrition in Ghana has also been very relevant to the Millennium Development Goal (MDG) objective of reducing by half the proportion of people suffering from hunger by 2105.

Effectiveness

Budget support provided to the Ministry of Food and Agriculture (MoFA) enabled the implementation of several policies, strategies and plans, as well as four key Programs, leading to increases in staple food and livestock production. However, the increase in crop production was due to an increase in cultivation area rather than increases in productivity. The expected increase in the number of agriculture extension agents did not materialize nor did the strengthening of farmer-based organizations.

Post-harvest losses are a serious issue in Ghana. The Government of Ghana (GoG) did not implement a comprehensive post-harvest loss action plan as planned. Linkages to markets and the value chain, in addition to improving infrastructure, are key factors to reduce harvest losses and improve farmers’ revenues. In addition, coordination among government ministries and departments was inconsistent across various agriculture related initiatives. This has implications for the future as decision-making and budgets shift to the regions and district level with greater decentralization. All this highlights the extent of the work that remains in achieving better returns for farmers.

As a leading donor to the agriculture sector, Canada influenced the development of the Ghanaian Country Cooperation Framework for the New Alliance for Food Security and Nutrition and successfully engaged with the Ministry of Food and Agriculture and the Ministry of Health in the development of the National Nutrition Policy, thereby making this a multi-sectoral effort.

Some key outcomes for improved nutrition in the northern regions included a drop in rates of acute malnutrition by 50-58% from 2008 to 2011 compared to a 36% reduction at the national level. This is attributable to improved coverage and capacity in community management of acute malnutrition (CMAM). In 2014, there were 41 districts, representing 50% of districts in the focus regions, providing CMAM services and in many of these the cure rate is above 60% and the death rate is below 5%. All districts also have the capacity to monitor nutrition indicators using internationally recommended methodologies.

The World Food Programme’s (WFP) School feeding program led to nearly doubling enrolment from 2006, with attendance improving from 89% in 2007 to 96% in 2009. The take-home ration component made a significant contribution to the improvement of girls’ education, including in districts with the highest gender disparity in Ghana. Two of the project regions, Upper West and Upper East, recorded a Junior High School Gender parity of 1.0, compared to 0.92 for the national level.

It was too early at the time of the evaluation to see tangible results from the research activities conducted under the research and development pillar. Reference was made to the completion of 12 of 17 funded projects in the 2013 Report on Agriculture, and fact sheets to support the dissemination of knowledge were produced. However, no further evidence on the results of these activities was found.

Sustainability

Overall, the Ghana Program made satisfactory progress towards assuring the sustainability of results. Two key contributing factors were the use of government systems to channel funds, which contributed to greater government buy-in, and capacity building. Enhancing management and monitoring systems and the capacity of personnel at the MoFA and Ministry of Local Government and Rural Development (MLGRD) were a particular contribution.

The evaluation also confirmed that the GoG was allocating budgets, including transferring funds to the district level, for current DFATD-supported initiatives. The District Development Facility (DDF), a multi-donor initiative with direct budget support to the districts, also saw the GoG devolving a significant proportion of development partner funds to the districts. The GoG is gradually taking over initiatives implemented through multilateral agencies such as school feeding and malnutrition care and management in the northern regions, as well as monitoring nutrition indicators using internationally accepted methods.

Remaining challenges to sustainability include uncertainty as to the level of government commitment to certain initiatives in the absence of donor funding, the challenge of integrating new processes into an existing system, and a whether or not there is long-term commitment for research and development activities.

Cross-cutting Themes

Gender Equality: The integration of gender equality into the design of programs and projects was consistent across all DFATD-funded initiatives. That said, actual implementation of gender strategies was found to be uneven; relatively strong in some smaller initiatives implemented in Ghana, but weaker within larger initiatives led by the GoG.

There was a notable contribution to the integration of gender equality issues and gender mainstreaming strategies into the MoFA’s policy processes, although there remains scope to scale up implementation. Likewise the MLGRD will need support as it further decentralizes through initiatives such as the District Development Facility.

The implementation of the Gender in Agricultural Development Strategy has been slower than expected and some key stakeholders within the Ministry have not been able to play their role fully. For instance, the Women in Agriculture Development Directorate (WIAD), which is one of seven directorates in MoFA, has been working to improve nutritional outcomes. While this is a crucial mandate and Canada has provided sector support to the MoFA, WIAD’s program funding from MoFA has been only about $200,000 per year - an amount deemed insufficient to play a significant role on gender and food security issues across Ghana.

Environmental Sustainability:The Ghana Program made satisfactory progress towards environmental sustainability. All actors (governmental, international or non-governmental, partners and agencies) implementing programs supported by Canada established processes for integrating environmental sustainability.

DFATD engaged management at the MoFA to integrate environmental sustainability into its plans and projects, leading to improvements in its performance on environmental sustainability. With technical assistance from DFATD, MoFA developed and officially adopted the Agricultural Land Management Strategy and Action Plan (2009-2015) in 2009. However, implementation of the action plan was slow due to lack of committed MoFA resources to support planned activities.

In the northern region, the Assistance to Ghanaian Food Insecure project contributed to slowing land degradation and soil erosion in intervention communities, while the Climate Change Resilience in Northern Ghana project (CHANGE) encouraged climate-friendly food production. The Food Security and Environment Facility also contributed to increased food production and alternative livelihood activities in an environmentally sustainable fashion.

Governance: Canada made a notable contribution to the processes of decentralization in Ghana through budget support to MoFA and the establishment of a District-Development Fund, which was a scaled-up version of the Canadian supported project District-wide Assistance Project (DWAP) implemented in the northern regions of Ghana. The institutionalization of the functional organizational assessment tool provides an incentive to metropolitan, municipal and district assemblies (MMDAs) to improve performance by tying annual funding levels to scores on performance measurement exercises.

Canada also played a significant role in helping to track the budgetary allocations from the MoFA to the regions and provide comparative data on all the MMDAs in Ghana. Initiatives to assist targeted communities in developing community action plans have also contributed to strengthening governance at the district level. These initiatives also provide an enabling environment for future initiatives related to food security.

Efficiency

The cost to manage the Ghana bilateral Program, including salaries and other overhead expenditures was 2.6% of total yearly disbursements.

The trigger system established by donors to ensure that certain targets were met by the government prior to receiving planned financial disbursements provides an incentive for MoFA to be efficient, but the sheer volume of triggers and disbursement tranches raises questions about the transaction costs for DFATD and the Ministry. The mid-term assessment of the budget support to MoFA suggested that the large number of triggers (12 in 2011; 11 in 2013) may distract from daily activities of the Ministry and lead to sub-optimal use of scarce qualified staff. A more focused approach may be required, with a smaller and more focused number of triggers.

Management Factors

The Ghana Program had appropriate instruments to manage and monitor their initiatives, such as performance measurement frameworks and sector working groups and steering committees. Risk management was also satisfactory.

The preparation of country strategy documents, including logic models and performance measurement frameworks, was completed in 2009 but only finalised in 2012 following corporate instructions. Overall, the multiple revisions and inconsistencies presented a challenge in tracking and reporting on results. While the evaluation ascertained that corrective actions were being undertaken, these were not always documented. Hence, it was difficult to assess how monitoring information had been used for project and program management decision-making.

In terms of ownership, alignment and harmonization, key principles of the Paris Declaration, modalities such as budget support to the GoG and initiatives implemented by it helped contribute to ownership, as did multilateral agency initiatives that worked closely with the government and used the latter’s systems.

The Ghana Program showed leadership in promoting donor harmonization in the agriculture sector through the Agriculture Working Group. It took tangible steps to promote greater harmonization – for example, undertaking a scoping study on the readiness of MoFA and donors to undertake a sector-wide approach and organizing the inaugural visit of key donors to the northern regions of Ghana.

Conclusions

- The Ghana Program is highly relevant and well aligned to the priorities of Ghana, particularly efforts to achieve the MDG 1 target of halving hunger by 2015. Canada’s focus on the three northern regions was highly relevant to the needs of the population given the disproportionately high levels of poverty, lack of access to basic services and level of malnutrition compared to other regions. The additional focus on water and sanitation there was an appropriate complement in achieving improved nutritional outcomes.

- The Program was also aligned with Canada’s G8 commitments most relevant to the Ghana context, and engagement in policy dialogue made a significant contribution to enabling conditions for food security, public sector reform, and decentralization.

- The level of results achieved was satisfactory, working mainly through budget support, which accounted for two-thirds of the disbursements in Ghana. Canada contributed to the development of key strategies and plans for agriculture development and to their implementation, which led to improved crop and livestock production.

- Government capacity was bolstered in the areas of public sector reform, financial management and in agriculture. More specifically, the Program contributed to an improved food and agricultural policy, improved financial management, a new performance management framework, and the integration of environmental sustainability and gender equality into these documents and tools.

- Given the emphasis of the Ghana Program on sustainable agricultural development, the lack of a clear long-term Program strategy or initiatives to promote value chain development or the development of farmer-based organisations should be addressed.

- A notable Canadian contribution has been support to the processes of decentralization. Targeted interventions at the district and the community level have served as a model for decentralization for Ghana in the years to come.

- There was satisfactory progress toward achieving sustainability. Institutional strengthening of MoFA and efforts to use local systems effectively and channel funds through the government were contributing factors. Ownership by the GoG was most evident in general budget support, sector budget support and the District Development Facility. Nutrition initiatives implemented through the WFP and UNICEF in the northern regions also used local systems. However, GoG operational budgets need to be secured for these programs to ensure long term sustainability.

- DFATD programming made a notable contribution to the integration of gender equality issues and gender mainstreaming strategies into policy and processes of MoFA, including M&E frameworks.

- Donor agencies, including DFATD, established processes for integrating environmental sustainability. There was ongoing support provided to Ghana’s Environmental Protection Agency to implement a National Action Plan on desertification. Some projects in the northern regions contributed on a small scale to slowing land degradation in the intervention communities and improving environmentally sustainable food production practices.

- While delays in the DFATD approval process put additional pressure on partners to achieve results in a shorter timeframe than planned, the efficiency of the Ghana Program was satisfactory overall, both in terms of cost to manage program activities and the level of results achieved. Still, the broad focus of DFATD budget support to MoFA with the number of triggers and disbursement tranches likely increased transactions costs for both partners, and may have unduly taxed human resources within the Ministry.

- Overall, the Program has exerted adequate efforts in managing for results and mitigating risks. Logic models and performance measurement frameworks existed and were generally used to monitor and report results on a regular basis.

Lessons Learned

- Initiatives implemented by the government, or in close concert with it, lead to increased ownership, capacity and sustainability.

- Implementing innovative pilot projects that demonstrate results at the community and district levels and have a good potential for scaling up can effectively complement program-based approaches. The District-wide Assistance Project is a good example: after demonstrating its effectiveness in the northern regions, it became the model for multi-donor support to the implementation of the District Development Facility nationwide by the MLGRD.

- In the context of a decentralized governance system, it is important for different ministries to coordinate their activities at all levels to provide better outcomes for the population. The experience linking nutrition and agriculture activities at various levels of government in the northern regions was a good example of this. Another example was the support provided by MOFA’s agricultural extension agents working at the district and community levels to the Food Security and Environment initiatives. Other Canadian-funded initiatives, such as the Investment Fund for Food Security, could have benefited from this approach to achieve greater results for the targeted communities.

- Supporting communities to develop local action plans, which include food security, gender and environmental sustainability, can lead to more appropriate applied research projects and more inclusive and responsive decision-making to meet community needs in the context of decentralized governance.

- Addressing such issues as productivity, post-harvest loss, the development of farmer-based organisations and strengthening extension services are essential to having a real impact on sustainable agricultural development.

- The use of a trigger system proved to be an effective mechanism to encourage governments to prioritise issues and for the Ghana Program to monitor progress alongside other donors. However, too many triggers and disbursement tranches can increase transaction costs; fewer well-designed triggers may be more effective.

Considerations for Food Security Programming, and Policy Framework

The findings and lessons from this evaluation of DFATD’s food security programming in Ghana and Ethiopia, which constitutes a significant proportion of its bilateral programming on this theme, suggest a number of considerations for the Department’s future programming and policy framework. These include:

- increasing support to smallholder farmers to move beyond crop and livestock production and improving their access to markets and to services that can add value to their products;

- creating or strengthening farmer-based organizations/cooperatives/common interest groups so as to build a critical mass of viable groups, to strengthen farmers’ bargaining power and ability to add value to their products;

- enhancing the linkages between the Food Security and Sustainable Economic Growth strategies to promote overall economic growth in agriculture, including support for the development of small (village/community level) and medium-size (district level) enterprises and facilitation of private sector investment in agri-businesses;

- mainstreaming nutrition in food security and agricultural development strategies, including a recognition of the multi-sectoral determinants of good nutrition status, particularly water and sanitation; and,

- planning and implementing applied research so that it can be affordably taken up by farmers to improve yields, food security, and income.

Recommendations – Overall

Recommendation 1: DFATD should review its performance management tools for country development programs to ensure that there is appropriate integration of project and program level reporting, as well as an adequate degree of consistency for investments from different delivery channels.

The practice of performance management of country level development results at DFATD has evolved in recent years. Country Strategies, Country Development Program Frameworks, and performance measurement frameworks have been used to articulate, track and report on sector and country-level outcomes. Project level reporting tools, such as the Investment Monitoring and Reporting Tool (IMRT), are also used. In IMRT, the Management Summary Report and Investment Performance Report serve, in part, to inform higher-level reporting. However, this and other country program evaluations undertaken recently have noted imperfect integration of these tools to higher levels (Program and Corporate), and inconsistencies in their application. Statements of immediate, intermediate, and ultimate outcomes across Country Program and project logic models are not always complete or consistent. Baselines, indicators and data sources are not always complete. Lower levels do not necessarily sum to higher levels in ways that are useful to managers. As well, for investments from multilateral and partnership channels that can be tracked to a specific country or region, there is a question of whether sufficient tools and reporting exist to allow an appreciation of the overall results of Canadian sponsored programming at the sector or country level. Efforts to address these questions deserve renewed emphasis.

Recommendations – Ethiopia and Ghana Country Programs

Recommendation 2: The Ethiopia and Ghana Programs should ensure that Performance Measurement Frameworks for their next generation CDPFs allow for effective monitoring of program level results.

Among others, attention should be paid to collecting sufficient baseline information and regularly tracking chosen indicators.

Recommendation 3: The Ethiopia and Ghana Programs should ensure that food security-related research initiatives are user-focused and serve to improve poverty reduction and economic growth outcomes.

Recommendation 4: DFATD should improve coordination of Canadian-funded research initiatives from different Branches throughout the planning cycle.

DFATD funds food security research projects through different modalities and Branches. In order for research results to be taken up by national counterparts and targeted beneficiaries, DFATD should ensure that planned projects have credible end-use strategies from the outset, which are aligned with the national poverty reduction and economic growth agendas in both countries. Increased coordination and communication between Branches, as calls for proposals are designed and as projects are implemented in the field, is also necessary for research results to be complementary and applied to best effect.

Recommendations – Ethiopia Country Program

Recommendation 5: The Ethiopia Program should continue to complement proven existing programming, like support for the Productive Safety Net Programme, with activities to increase the self-sufficiency of beneficiaries.

The provision of additional funding and technical assistance to initiatives that emphasize the safety net aspects of food security programming in the districts where food insecurity is most pronounced should move more households out of a chronic dependency on food assistance and provide them with increased income, thereby improving their self-sufficiency. While the focus of PSNP is to increase basic food security by providing cash or food in exchange for labour on public works, increasing the funding in these food insecure districts for value-added or alternative income generation activities would help to ensure that PSNP graduates do not revert to a dependency on PSNP assistance. This would also support the Government of Ethiopia’s efforts to shift funds to higher value economic growth activities.

Recommendation 6: In its future programming, DFATD-development should ensure that Canadian-funded projects implemented by Canadian implementing agencies are adequately aligned with Government of Ethiopia systems and processes in order to promote ownership and sustainability.

The Ethiopian Government has a policy of maintaining tight control over development interventions in the country by outside agencies. It has also been very good at designing its own programs and initiatives with a view to systematizing processes and practices to ensure sustainability. The corollary of this practice is that initiatives that are not well coordinated with the Ethiopian planning and budgeting systems may not be taken seriously by the government and have a reduced chance of being sustained or supported once external development partner funding ceases. While understanding that sustainability is usually included in project design, DFATD should nonetheless ensure that any Canadian projects are coordinated with the government to the extent possible.

Recommendations - Ghana Country Program

Recommendation 7: The Ghana Program should consider supporting innovative pilot projects , such as those in food security, that have a potential to be scaled up nationally.

The Ghana Program should leverage its experience in demonstrating effective programming at the district and community levels by increasing funding to initiatives that have the greatest potential to enhance the economic benefits to and the resilience of farmers in the face of climate change. The Ghana Program should continue to focus on such initiatives in the northern regions as they can help to reduce poverty in a targeted manner while also strengthening national systems from the bottom-up.

Recommendation 8: The Ghana Program should continue assisting the GoG to strengthen multi-sectoral linkages at the community and district levels.

DFATD should build upon what is has learned using multi-sector approaches to foster greater coordination among all stakeholders at local levels – for example, extension services, farmer-based organizations and the research establishment – to ensure that the priorities of communities are integrated in district plans, that the transfer of technologies to farmers is accelerated and that resources are leveraged more effectively to address the food security needs of the population in a more comprehensive fashion.

Recommendation 9: The Ghana Program should strengthen its approach to addressing gender issues at various levels of government, including assistance to the MoFA to strengthen and leverage existing gender resources at the national and district level, so that these more effectively support food security-related initiatives to the benefit of communities.

In future programming, the Ghana Program should build on work done to strengthen MoFA policies and strategies, and in particular, to strengthen WIAD gender resources to play a more effective role as policy advisors on food security issues and to become focal points for programming at the district and community levels.

Recommendation 10: If the Ghana Program continues to provide sector budget support, it should ensure that the trigger and disbursement system is appropriately calibrated to national capacities to efficiently initiate, monitor, and measure desired changes.

Emerging evaluation evidence, and feedback from national authorities, suggests that strong national ownership and capacity to implement well-focussed reforms is more effective than numerous donor-driven ones.

1.0 Introduction

The Ethiopia and Ghana Country Program Cluster Evaluation was conducted between December 2013 and December 2014. It assessed Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development’s (DFATD)Footnote 1 performance in providing development assistance to Ethiopia and Ghana between 2008/9 and 2013/14, with particular focus on food security. This evaluation is intended to provide key lessons and recommendations to support evidence-based decision making on policy, expenditure management and program improvement.

The first two sections of the report cover the rationale, purpose, approach and methodology and DFATD’s context by country. Findings, conclusions and lessons learned for Ethiopia and Ghana are then presented in Sections 3 and 4, respectively. Section 5 presents considerations for food security programming and policy framework and Section 6 presents recommendations.

1.1 Rationale and Purpose

In accordance with the Federal Accountability Act (2006), and the Treasury Board Policy on Evaluation (2009), the purpose of the Ethiopia and Ghana Country Program Cluster Evaluation is accountability and program improvement. This evaluation is one of the first Country Program evaluations to be conducted as a cluster of two country programs with a focus on one thematic area. It samples projects from three former CIDA Branches as part of the Country Program – Geographic Programs Branch, Multilateral and Global Programs Branch and Partnership with Canadians Branch.

In addition to DFATD’s senior management and Program managers, the audience for this evaluation includes the Governments of Ethiopia and Ghana, partner civil society and multilateral organizations, and other development agencies working with DFATD in Ethiopia and Ghana. The evaluation is expected to enhance stakeholder understanding of achievements and lessons from DFATD’s development interventions in both countries.

1.2 Objectives and Scope

1.2.1 Objectives

The objectives of the evaluation were:

- To assess the overall performance of the Ethiopia and the Ghana Country Programs (fiscal year 2008/09 to fiscal year 2012/13) in achieving development results, with a particular focus on food security; and,

- To provide Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada with relevant information for future international development programming in the two countries especially with respect to food security.

1.2.2 Scope

The scope of this evaluation, as envisaged in the Terms of Reference, included an assessment of:

- The overall performance of the Country Programs with respect to relevance and aid best practices (alignment, harmonization, ownership), effectiveness (including in the use of policy dialogue) and efficiency (based on a sample of projects with a thematic focus in food security);

- Cross-cutting themes (gender equity, environmental sustainability, and governance), adequacy of coordination, linkages and synergy across DFATD’s Programming, as well as how DFATD Programming complemented national food security investments in each country;

- DFATD’s ability to meet commitments with regard to the effectiveness of its international development assistance, including alignment with the Paris Declaration (2005) and the Accra Agenda for Action (2008). The evaluation also took into account the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and the main measures taken by DFATD to implement the action plan for increasing the effectiveness of aid.

2.0 Approach and Methodology

The assessment of performance of the Country Programs in Ethiopia and Ghana was carried out primarily by reviewing a representative sample of projects, as well as policy dialogue activities, in each country. The extent to which interventions attained the outcomes described in their logic models and performance measurement frameworks (PMF), as well as unanticipated positive and negative impacts, was assessed using the Evaluation Design Matrix which appears as Appendix A. sol

2.1 Methods

The evaluation used mixed-methods—document and literature review, key informant interviews, focus groups and case studies/site visits, and an analysis of program and national statistics, where available, to gather multiple lines of evidence. There were focus groups with beneficiaries at different levels, including women and youth. The team interviewed 212 key informants in Canada, Ethiopia and Ghana (Appendix G, Table 1) and reviewed more than 245 Program and project documents, in addition to relevant literature (Appendix F).

| Informant | HQ | Ethiopiah | Ghanah |

|---|---|---|---|

| DFATD HQ | 46 | ||

| DFATD in Embassy | 11 | 10 | |

| ECCO/PSU | 10 | 6 | |

| Development Partners | 18 | 19 | |

| Government / Government Agency | 24 | 33 | |

| NGO / Other Non-Profit and Research Institutions (Ethiopia, Ghana and Canada) | 22 | 13 |

There were project site visits in Ethiopia and Ghana (Appendix H). During field missions to Ethiopia, there were visits to project sites in nine woredas (districts) in two regions (Tigray and Amhara); and in Ghana to sites in six districts spread across three regions (Upper West, Upper East and Northern).

Project Sample

A sample of 40 projects was selected for in-depth review (Appendices B and C). The breakdown was as follows: 20 projects in the Ethiopia Program ($344.32 million—54.3% of total disbursements and 82.3% of food security disbursements) and 20 projects in the Ghana Program, ($223.87 million—44.8% of total disbursements and 92.5% of food security disbursements).Footnote 2

The criteria used to select the sample of projects included initiatives that: a) met DFATD’s food security priorities, as well as contributed to improved food security in each country; b) represented the various delivery channels (bilateral, multilateral and global partnerships with Canadians); c) reflected the main delivery modalities used by each Country Program; and d) were at least 50% of the total of the DFATD expenditures in each country’s for its aid program. In addition to these criteria, the sample included a mix of status (closed/operational), investment type (e.g. Program-based approach, projects), and delivery mode - core support, responsive funding and directive funding.Footnote 3

Data Collection and Analysis

Data collection for this evaluation largely relied on: a comprehensive document review; semi-structured interviews with stakeholders at various levels; and discussions with project beneficiaries during site visits. Data collection began with an initial review of documents and interviews in Canada followed by field missions to Ethiopia (February 24 – March 7, 2014) and Ghana (March 10 – 21, 2014). The in-country evaluation team included a mix of Canadian and local consultants.

The data collected was tabulated and aggregated for analysis. A content analysis of documents and interview notes helped to draw out emerging themes and issues. The sampled projects were assessed on a DFATD rating scale (see Table 2.2 below) following the document review and ratings from key informants and aggregated at the Program level in combination with the other sources of data.

| Nominal Scale | Definition |

|---|---|

| Highly Satisfactory | The Program meets all the evaluation indicators for the given criterion |

| Satisfactory | The Program meets most evaluation indicators for the given criterion |

| Neither Satisfactory or Unsatisfactory | Rating not applicable or mixed results observed |

| Unsatisfactory | The Program does not meet most of the evaluation indicators for the given criterion |

| Highly Unsatisfactory | The Program does not meet any of the evaluation indicators for the given criterion |

The evaluation team triangulated by comparing information collected through various lines of evidence in the data collection and analysis stages. This included a comparison of findings and observations made by Canadian and local evaluation team members following key informant interviews, focus groups and field visits in Canada and in Ethiopia with formal program/project reports and analyses that were available. A summary of ratings by project can be found in Appendix L and M.

Limitations and Challenges

As with many evaluations of similar scope and scale, there were challenges that had to be addressed, including:

- Shortcomings in project documentation, including:

- A limited number of independent project evaluation reports;

- Different performance measurement frameworks and reports for bilateral, multilateral and partnership projects;

- Differences in the templates for field/monitoring reports; and,

- Limited detail in project budgets, which limited the analysis of efficiency and economy.

- Inconsistencies between the Country Program logic models and performance measurement frameworks in both the Country Programs. For example, some of the specified logic models results in the Ethiopia Program were not reflected in the PMF, and hence no indicators were identified. In these instances, the evaluation team had to rely on progress reports and key informants’ interpretation of progress;

- The nature of donor-harmonized and government-led initiatives where investment is generally pooled in multi-donor accounts or channelled through government financial systems made it difficult to attribute achievement of results to DFATD directly. In these instances, since DFATD was often a significant contributor, our comments pertain to the overall evaluation results of the project/or program compared to what was envisioned in the DFATD approval documentation;

- This evaluation covers the respective Country Development Program Frameworks from 2008/09–2012/13. Programming was designed and initiated in 2008 but CDPFs were revised during the evaluation period. The Food Security Strategy was approved in 2009, thereby rendering it somewhat challenging to assess the extent to which programming was aligned to and consistent with the Strategy; and,

- Data constraints rendered a thorough assessment of the efficiency of each Program challenging.

2.2 DFATD Context

In 2007, the Government of Canada established its Aid Effectiveness Agenda, committed to making Canada’s international co-operation more efficient, focused and accountable. Since then, Canada has taken important steps to reform its aid program in accordance with this agenda and in line with international agreements and recognized best practices. For example, Canada untied all food aid in 2008 and all non-food aid in 2012.

Within the framework of this Agenda, the Government of Canada also established three priority themes to guide its international development work: increasing food security; securing the future of children and youth; and stimulating sustainable economic growth. These three priority themes – in addition to Canada’s global commitment to the Muskoka Initiative (2010) to improve maternal, newborn and child health – guide DFATD’s international assistance. Additionally, three cross-cutting themes: increasing environmental sustainability; advancing equality between women and men; and helping to strengthen governance are meant to be integrated into all of DFATD’s international development programs and policies.

3.0 Ethiopia Country Program

3.1 Country Context

Ethiopia is one of the world’s poorest countries despite recent development progress (Table 3.1). In 2012, Ethiopia had a Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of $43.62 billion, with an annual growth rate high of 8.5%.Footnote 4 However, while GDP growth has remained high, per capita income is among the lowest in the world (gross national income (GNI) per capita at $410 in 2012).Footnote 5 The second most populous country in Africa, Ethiopia’s population was estimated at 91.73 million in 2012. Of this, 29.6% lived below the national poverty line and 80% lived on less than US$2 per dayFootnote 6. Ethiopia is ranked 173 of 187 countries on the Human Development Index (HDI).Footnote 7 According to the latest reports, Ethiopia is on track to meet most of the MDGs by 2015 if current progress continues. The Government of Ethiopia and the United Nations are now accelerating efforts to meet the MDGs that are slightly off-track (Gender Equality and Women‚ Women's Empowerment, Maternal Health and Environmental Sustainability) through the Growth and Transformation Plan and the United Nations Development Assistance Framework.Footnote 8

| Gross National Income (World Bank) | Poverty (World Bank) | Global Hunger Index (IFPRI) | Human Development Index (UNDP) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source: Compiled from World Bank (2013); UNDP (2014); IFPRI (2014) | ||||

| Most Recent | USD 380 (2012) | 29.6% (2011) | 25.7 (2013) | 2013 – 0.435 (173/187) |

| Past | USD 270 (2008) | 38.9% (2004) 44.2% (1999) | 31.0 (2005) 42.7 (1995) | 2007 – 0.411 (171/182) 2005 – 0.406 (169/177) |

Ethiopians suffer from low life expectancy, high rates of infant mortality (52 deaths per 1000 live births), under-five child mortality (198 per 1000 live births) and maternal mortality (680 per 100,000 live births), with an HIV infection rate of 1.4%.Footnote 9 The main development challenge has been food security, with 80% of Ethiopia’s population engaged in low-productivity, rain-fed, subsistence agriculture that is highly vulnerable to short-term shocks caused by drought and economic crises. Other threats include the long-term impacts brought on by climate change, land degradation, and population density. Ethiopia’s economy is largely agriculture-based, yet the agricultural sector suffers from poor cultivation practices and frequent drought.Footnote 10

Key issues pertaining to DFATD cross-cutting themes include the following:

- Ethiopia ranks 126th of 155 countries in the Gender Development Index (GDI, 2013).Footnote 11 In 2010, 50.2% of the female population lived in rural Ethiopia and 73.5% of economically active women worked in the agricultural sector.Footnote 12 The National Action Plan on Gender Equality (2006–2010) provides the framework for mainstreaming gender issues.

- Ethiopia’s ecological system is highly fragile and vulnerable to climate change, leading to a greater frequency of drought years, unpredictable rainfall patterns and shorter rainy seasons. This is compounded by population pressure and stresses on natural resources, especially land. Soil erosion, land degradation, deforestation, overgrazing, and poor water management are all critical environmental issues undermining Ethiopia’s potential for achieving food security. To help deal with these issues, the Government of Ethiopia (GoE) established policy frameworks, including an Environmental Policy (1997) and a National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (2005); however, there is a need for more clarity on operational/implementation frameworks to integrate climate change adaptation and mitigation measures into sector plans and investments. It is also necessary to strengthen water resource management and to ensure sustainable development.Footnote 13

- Ethiopia’s public administration capacity and its public financial management system are generally sound compared to its HDI cohort countries, which have similar HDI characteristics. Historically, Ethiopia has had a reputation for not tolerating corruption.Footnote 14 However, Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index score for Ethiopia in 2013 was 33, and Ethiopia was ranked 111 of 177 countries.Footnote 15 Some of the issues in public administration that affect development partner support for Ethiopia’s programming and service delivery, include high staff turnover, political appointments, unattractive salaries, unfilled posts, and lack of technical competence. Vacancies and staff turnover are also problematic in the districts, particularly the poorest areasFootnote 16, where isolation makes assignments unattractive, and budgets are insufficient to fill staff complements.

Since Ethiopia’s 2005 post-election crisis, DFATD, along with other major donors, stopped using general budget support as a delivery modality. However, a few donors have since provided funding to the GoE directly, although not as direct budget support.

Government regulations have sometimes led to restricted civil society growth and made it difficult to implement foreign-funded development initiatives. Regulations were introduced in 2009Footnote 17 that restricted local civil society organisations (CSOs)/charities that received more than 10% of their funds from overseas for human rights initiatives.Footnote 18 Likewise, another set of new laws stipulating that only 30% of non-governmental organization (NGO) budgets could be used for administrative expenses was interpreted in 2011 to include most travel and training costs. This has proved challenging for many NGOs and has caused them to limit training, capacity building, and monitoring and evaluation activities, all of which are important to knowledge and capacity transfer and sustainability of interventions.Footnote 19 In 2010, the World Rule of Law Index report ranked Ethiopia 88 out of 99 countries.Footnote 20

The GoE adopted a five-year Growth and Transformation Plan (GTP) 2010/11–2014/15, which places special emphasis on the role of agriculture as a major source of economic development in Ethiopia. The GoE’s budget allocation to benefit the poor is the highest in Africa.Footnote 21 In particular, the government is addressing food insecurity through its long-term strategy of Agricultural Development-led Industrialization (ADLI).Footnote 22

Following the ADLI strategy and building on achievements from its Plan for Accelerated and Sustained Development to End Poverty (PASDEP), the GTP has set priorities that will intensify productivity by smallholders and support market-oriented agriculture. In 2010, the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development launched the Food Security Program with a focus on rural areas. Additionally, the GoE created the Agricultural Transformation Agency in 2010, which reports to an Agricultural Transformation Council chaired by the Prime Minister of Ethiopia and vice-chaired by the Minister of Agriculture. The Agricultural Transformation Agency has been tasked with supporting all key stakeholders (including the Ministry of Agriculture) to transform Ethiopia’s agriculture sector so the country can reach middle- income status by 2025. Canada supported the Food Security Program but not the Agricultural Transformation Agency.

Overall Development Portfolio

Canada ranked between the seventh and fourth largest donor to Ethiopia from 2009 – 2013. Other major donors included the World Bank’s International Development Assistance fund (IDA), the United States, the African Development Fund, the United Kingdom and Japan.

| Donor | Rank | 2009 | Rank | 2010 | Rank | 2011 | Rank | 2012 | Rank | 2013 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source: Compiled from World Bank (2013); UNDP (2014); IFPRI (2014) | |||||||||||

| Bilateral | Canada | 7 | 87.73 | 4 | 287.64 | 7 | 103.76 | 5 | 204.88 | 7 | 113.2 |

| Japan | 6 | 104.93 | 7 | 82.53 | 6 | 114.36 | 6 | 111.73 | 6 | 155.63 | |

| UK | 3 | 340.46 | 3 | 409.06 | 3 | 548.66 | 3 | 420.92 | 3 | 518.18 | |

| US | 2 | 726.03 | 1 | 879.33 | 1 | 708.64 | 2 | 736.45 | 2 | 619.4 | |

| EU Institutions | 5 | 218.77 | 5 | 229.05 | 4 | 239.17 | 4 | 220.39 | 5 | 116.18 | |

| Multilateral | AFDF | 4 | 307.14 | 6 | 149.46 | 5 | 233.34 | 7 | 97.43 | 4 | 346.91 |

| IDA | 1 | 1037.53 | 2 | 664.93 | 2 | 708.53 | 1 | 741 | 1 | 955.13 | |

DFATD disbursed $633.72 million to the Ethiopia Program from 2008/09 to 2012/13, of which about 65.8% ($416.67 million) went to initiatives related to food security.

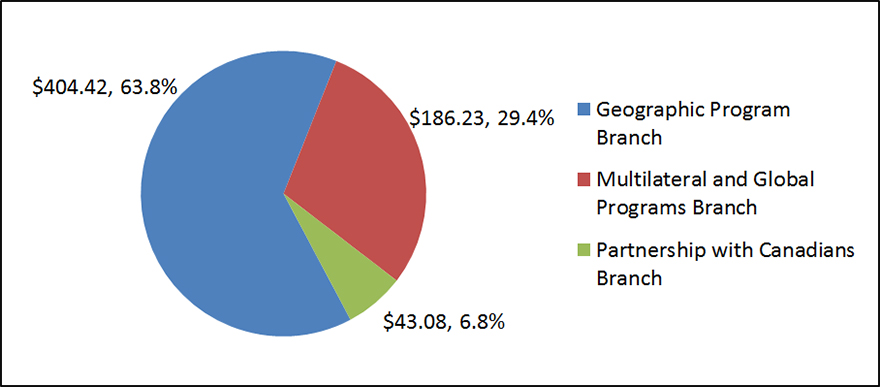

Figure 3.1: Disbursements in Ethiopia by DFATD Delivery Channels (2008/09 to 2012/13), millions

Figure 3.1 Text Alternative

Geographic Program Branch: $404.42 (63.8%)

Multilateral and Global Programs Branch: $186.23 (29.4%)

Partnership with Canadians Branch: $43.08 (6.8%)

Note: This data relates to the period before amalgamation and, as such, uses the former CIDA Branch titles.

The main delivery channel was the Geographic Programs Branch, which accounted for 63.8% of disbursements. The other two delivery channels were Multilateral and Global Programs Branch, which accounted for 29.4% of disbursements and the Partnership with Canadians Branch for 6.8% of disbursements (Appendix D, Figure 1).

Disbursements were made either through Program-Based Approaches (PBAs) (49.1%) or through projects (50.9%). PBAs in Ethiopia included multi-donor pooled funds and other PBA support activities, including technical assistance (see Appendix D). In terms of Program delivery models, while 57% of the disbursements were responsive, 38.5% were core funding and only 4.4% were directive. Disbursements were made to a number of partners/implementing organizationsFootnote 23, 61% to CSOs, 37% to multilaterals and 2% to governments and others. However in terms of dollar value, 77.9% of DFATD investments went through multilaterals (57.2% through multi-donor trust funds/other PBAs, which is 44.6% of total disbursements), 19.4% through CSOs and the rest (2.7%) through governmental and other organizations.

DFATD’s Food Security Portfolio in Ethiopia

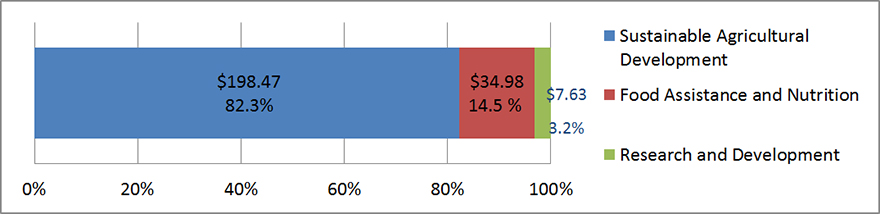

From 2008/09–2012/13, Canada disbursed $416.54 million in Ethiopia for initiatives related to food security. A majority (55.1%) of these disbursements were attributed to the Food Assistance and Nutrition pillar of the Food Security Strategy. The Sustainable Agricultural Development pillar accounted for 41.4% of the food security portfolio, while the Research and Development pillar accounted for 3.5% (Figure 3.2).

Figure 3.2: Food Security Disbursements in Ethiopia by Pillar (2008/09–2012/13), millions

Figure 3.2 Text Alternative

Sustainable Agricultural Development: $172.53 (41.4%)

Food Assistance and Nutrition: $229.48 (55.1%)

Research and Development: $14.53 (3.5%)

Source: Compiled from DFATD database

Disbursements in Ethiopia by sub-sector and related to the Food Security Strategy, were as follows: development food assistance (29.1%), agronomic and post-harvest activities (26.1%), enabling activities and support services (15.4%), emergency food assistance (12.7%), nutrition (12.5%) and agricultural research for development (3.5%).

3.2 Findings - Development Results

Relevance

Main Findings

- Overall, the Ethiopia Program was found to be relevant and well aligned to the GoE priorities as well as to DFATD priorities and commitments. The DFATD Country Program supports the GoE flagship programs that directly targeted reducing hunger and extreme poverty. Other projects supported by Canada, which were focused on improved agricultural productivity and practices, are also directly relevant to the GoE priority of reducing hunger and extreme poverty.

- The evaluation found that Canada had met its various global G8 commitments in Ethiopia through the L’Aquila Food Security Initiative, New Alliance for Food Security and Nutrition, Scaling-Up Nutrition, Food Assistance Convention and the Muskoka Initiative.

- The evaluation also found that projects approved and additional funding provided by Canada for the Ethiopia Country Program have been consistent with the Food Security Strategy, and Canadian national and global priorities.

The criteria used to assess relevance were based on whether the Country Program was aligned with: a) Ethiopian priorities as expressed in the Plan for Accelerated and Sustained Development to End Poverty 2005/06–2009/10 and the Growth and Transformation Plan (2010/11–2014/15); b) the MDGs; c) international commitments made by Canada (G8 L’Aquila Food Security Initiative, New Alliance for Food Security in Africa, Scaling-up Nutrition, the Food Assistance Convention); and d) the DFATD Food Security Strategy.

The GoE has placed agricultural development at the centre of its poverty reduction strategy. A central strategy of the recently completed PASDEP, market-based agricultural development focusing on Ethiopia’s 13 million smallholder farm households, was given high priority by the GoE.Footnote 24 This strategy has been further emphasized in the new five-year Growth and Transformation Plan 2010/11–2014/15, as well as Ethiopia’s Agricultural Sector Policy Investment Framework 2010–2020. The evaluation found that given that the DFATD Country Program directly supported Ethiopian government programming that supports the Growth and Transformation Plan either directly or indirectly, it was well aligned with the GoE’s poverty reduction strategies during the evaluation timeframe.

The need for increased investments that promote food security, such as watershed rehabilitation, also feature prominently in the Growth and Transformation Plan and in Ethiopia’s Agricultural Policy and Investment Framework 2010–2020, which was completed in September 2010 under the Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Program process. A total of 10.2 million hectares of degraded land is targeted for rehabilitation in order to improve agriculture production and reduce food insecurity. The direct relevance of the DFATD Ethiopia Country Program to these priorities was evident in Canada’s investment in the important GoE flagship programs: the Productive Safety Net Program (PSNP), the Agricultural Growth Program (AGP), and the more recent Sustainable Land Management Project. The PSNP is a cornerstone of Ethiopia’s National Food Security Strategy.

By supporting the GoE flagship programs described above, which are directly targeted at reducing hunger and extreme poverty, as well as many of the other projects supported by Canada that are also targeting improved agricultural productivity and practices, DFATD Programming is also directly relevant to MDG 1. Canada has also supported various global initiatives in Ethiopia through its G8 Commitments, namely the L’Aquila Food Security Initiative, the New Alliance for Food Security and Nutrition, Scaling-up Nutrition, the Food Assistance Convention and the Muskoka Initiative.

The evaluation also found that projects approved and additional funding provided by Canada for the Ethiopia Country Program have been consistent with the DFATD Food Security Strategy, as well as other DFATD priorities. For example, the additional $35 million provided to the PSNP was highly consistent with the Nairobi Strategy issued on September 9, 2011 at the Summit on the Horn of Africa Crisis.

The Growth and Transformation Plan has identified private sector led growth in agriculture as an important element of the Ethiopian Growth strategy. The GoE would like to focus on building up micro and small scale industry in order to advance its objective of agriculture led growth. The country is starting to experience some investment in agribusiness, a trend that is likely to increase in the future. The Canadian program could support this trend by linking Canadian and Ethiopian businesses through trade and investment. This would be consistent with the bilateral Program’s efforts to focus on sustainable economic growth.

Effectiveness

Main Findings

- The Ethiopia Program focused close to half of its programming ($176 million) during the evaluation period on support for one of the Government of Ethiopia’s flagship programs, the Productive Safety Net Program. Independent studies have confirmed a consistent and significant decrease in the food gap in the targeted PSNP districts and that approximately 2.5 million people were able to graduate out of PNSP since 2005. Canada made a significant contribution to these results.

- Support for the PSNP and other complementary initiatives have increased resilience to drought and other shocks. Ethiopia was not as badly affected as other countries in the region during the 2011 Horn of Africa drought in large part due to the effectiveness of PSNP.

- Canada supported the GoE’s focus on improving nutrition that led to improved nutritional status in 100 food insecure districts and increased school enrolment with the provision of meals and take-home rations for girl students.

- The Program contributed to increased productivity and incomes in the area of sustainable agricultural development, including the rehabilitation of over one million hectares of degraded land, training of 58,000 farmers in new methods (43,000 focused on improved crop production, 12,000 on livestock and 3,000 on conservation), the creation of 1,500 farmer innovation groups and 263 primary cooperatives, and initiation of 125 irrigation schemes.

- A number of projects and activities contributed to strengthening Ethiopia’s research capacity.

- The Program has been active and effective in policy dialogue through the Development Action Group (high level), donor coordination groups and project level working groups. Canada currently chairs the Rural Economic Development and Food Security Working Group and is active in the PSNP donor coordination committee and the AGP working group among others.

A sample of 20 projects was assessed, from which the largest proportion of disbursement was to two of the Government of Ethiopia’s flagship programs – the Productive Safety Net Program and the Agricultural Growth Program. The narrative of this report is organized around the three pillars of DFATD’s Food Security Strategy: food assistance and nutrition; sustainable agriculture and development; and research and development.

Food Assistance and Nutrition

The projects that formed the backbone of the Food Assistance and Nutrition pillar included the Productive Safety Net Program, the Safety Net Support Facility and support to the World Food Programme (WFP). There was also a major initiative to improve nutritional outcomes implemented by UNICEF.