Evaluation of the Anti-crime Capacity Building Program and Counter-terrorism Capacity Building Program – FINAL REPORT

Global Affairs Canada Inspector General Office Evaluation Division

May 2016

Table of Contents

- Abbreviations, Acronyms and Symbols

- Acknowledgements

- Executive Summary

- 1.0 Introduction

- 2.0 Evaluation Objectives and Scope

- 3.0 Evaluation Approach & Methodology

- 4.0 Evaluation Findings

- 4.1 Relevance Issue 1: Continued Need for the Programs

- 4.2 Relevance Issue 2: Alignment with Government Priorities and Other Gac Programs

- 4.3 Relevance Issue 3: Consistency with Federal Roles & Responsibilities

- 4.4 Performance Issue 4: Achievement of Expected Outcomes

- 4.5 Performance Issue 5: Demonstration of Efficiency & Economy

- 4.5.1 Program Focus

- 4.5.2 Resource Utilization

- 4.5.3 Project Approval Process

- 4.5.4 Governance Structure

- 4.5.5 Program Efficiency

- 4.5.6 Cost-effectiveness of Project Delivery

- 4.5.7 Equipment Supply

- 4.5.8 Performance Measurement

- 4.5.9 Information and Knowledge Management Systems

- 4.5.10 Integration of Gender-related Issues

- 4.5.11 Project Management

- 4.5.12 Program Delivery Mechanisms

- 4.5.13 Coordination with Other Donors

- 4.5.14 Lessons and Good Practices

- 5.0 Conclusions of the Evaluation

- 6.0 Recommendations

- 7.0 Management Response and Action Plan

- Appendix 1: List of Findings

- Appendix 2: Suggested Steps to Implement Recommendations

- Appendix 3: Ctcbp and Accbp Budget Estimates

- Appendix 4: Evaluation Matrix

Abbreviations, Acronyms and Symbols

- ACCBP

- Anti-Crime Capacity Building Program

- ADM

- Assistant Deputy Minister

- AVC

- Annual Voluntary Contribution

- CBSA

- Canada Border Services Agency

- CBP

- Capacity Building Program (ACCBP, HSE, CTCBP)

- CBRNE

- Chemical, Biological, Radiological, Nuclear, Explosives

- CCC

- Canadian Commercial Corporation

- CFT

- Combating the Financing of Terrorism

- CICAD

- Inter-American Drug Abuse Control Commission

- CIDA

- Canadian International Development Agency

- C-IED

- Countering Improvised Explosive Devices

- CSIS

- Canada Security Intelligence Service

- CTCBP

- Counter-Terrorism Capacity Building Program

- CVE

- Countering Violent Extremism

- DEC

- Department Evaluation Committee

- DG

- Director General

- DND

- National Defence

- EAC

- Evaluation Advisory Committee

- EU

- European Union

- FATF

- Financial Action Task Force

- FINTRAC

- Financial Transactions and Reports Analysis Centre of Canada

- FTF

- Foreign Terrorist Fighter

- GAC

- Global Affairs Canada

- GoC

- Government of Canada

- GPP

- Global Partnership Program

- GPSF

- Global Peace and Security Fund

- HSE

- Human Smuggling Envelope

- IAE

- International Assistance Envelope

- ICT

- International Crime and Terrorism Division

- IFM

- International Security and Crisis Response Branch

- IGC

- Capacity Building Programs Division

- IGD

- Security Threat Reduction Bureau

- IO

- International Organization

- IOM

- International Organization for Migration

- ISC

- Interdepartmental Steering Committee

- LEMI

- Law Enforcement, Security, Military and Intelligence

- MoU

- Memorandum of Understanding

- NAM

- Needs Assessment Mission

- NGO

- Non-Governmental Organization

- OAS

- Organization of American States

- OECD

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development

- OGD

- Other Government Department

- PAD

- Project Approval Document

- PIA

- Project Initiation Authorization

- PM

- Performance Measurement

- PRC

- Project Review Committee

- PS

- Public Safety

- RCMP

- Royal Canadian Mounted Police

- SC

- Steering Committee

- SOPs

- Standard Operating Procedures

- TBS

- Treasury Board Secretariat

- UNODC

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime

- UNSCR

- United Nations Security Council Resolution

- ZID

- Office of the Inspector General

- ZIE

- Evaluation Division

Acknowledgements

The Evaluation Division (ZIE), Office of the Inspector General (ZID) of the Department of Global Affairs Canada (GAC), would like to thank the staff and management of the Anti-Crime Capacity Building Program (ACCBP) and the Counter-Terrorism Capacity Building Program (CTCBP) for their cooperation, and the members of the Evaluation Advisory Committee (EAC) for their guidance and advice. Special thanks to all of the representatives of ACCBP and CTCBP partner organizations who agreed to be interviewed for the evaluation.

Executive Summary

This summative evaluation of the Anti-Crime Capacity Building Program (ACCBP) and the Counter-Terrorism Capacity Building Program (CTCBP) was conducted by the Evaluation Division (ZIE), Office of the Inspector General (ZID), of the Department of Global Affairs Canada (GAC) as part of the departmental Five-Year Evaluation Plan. The evaluation was conducted according to the Treasury Board Policy on Evaluation. The target audiences for this evaluation report are GAC’s senior management, program managers, other government departments (OGDs) who partner in the delivery of the programs, as well as the Canadian public.

Background

CTCBP was created in 2005 with a mandate to provide assistance to foreign states in the form of training, provision of equipment, technical and legal assistance to enhance their capacity to prevent and respond to terrorist activities. Assistance provided by CTCBP is global in coverage and targeted to countries and regions with identified needs. A separate Sahel Program envelope was created in late 2010 for that specific geographic region. This special envelope is managed by CTCBP.

ACCBP was established in December 2009 to enhance the capacity of beneficiary states, government entities and international organizations to prevent and respond to threats posed by transnational criminal activity in the Americas. As of 2015 the ACCBP has a global scope with a focus on the Americas. In 2011, a separate Human Smuggling Envelope (HSE) was introduced to address those operations destined for Canada. HSE had a global scope, with a particular focus on Southeast Asia and more recently West Africa. This special envelope is managed by ACCBP.

Evaluation Scope and Objectives

The evaluation focused on programming over the last five years, i.e. from FY 2010-2011 to FY 2014-2015. The evaluation also followed up on the recommendations from the 2009 formative evaluation of CTCBP, and the 2012 formative evaluation of ACCBP.

The evaluation’s key objectives were to evaluate the relevance of ACCBP and CTCBP; evaluate their performance in achieving expected outcomes; examine synergies between the two programs and other GAC programming in security and development; gather lessons and make recommendations for improved management and delivery of ACCBP and CTCBP.

Evaluation Approach and Methodology

The evaluation utilized a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods and multiple lines of inquiry. Qualitative methods including interviews with 175 stakeholders, observation through site visits to 11 countries, document review and project file review were used to respond to all of the evaluation issues. These methods were complemented by quantitative methods to assess administrative data and other program information.

Key Findings

The evaluation found that for the 2011-15 period, there was a continuing need for the Capacity Building Programs: CTCBP to combat significant ongoing threats from international terrorism networks, particularly in the Middle East, North Africa and Asia; ACCBP to address organized crime and drug trafficking in Latin America and the Caribbean; and HSE to prevent human smuggling operations in Southeast Asia and West Africa. The Capacity Building Programs aligned with GoC policies and priorities. There was good consultation among the Capacity Building Programs, however coordination could be improved with other GAC security and development programs.

There was evidence that ACCBP, HSE and CTCBP made progress towards expected results at the immediate level, but there was little data available to assess achievement of intermediate outcomes. Beneficiaries interviewed during site visits expressed a high level of satisfaction with the capacity building programs and implemented projects were deemed successful in meeting their needs. The evaluation found that longer-term capacity building projects tended to be more sustainable than one-time training. CTCBP, ACCBP and HSE increased Canadian expertise, leadership and visibility in international security programming.

In assessing efficiency and economy, the evaluation found that programming focused on fewer countries and projects was more effective than spreading funding too thinly. ACCBP and CTCBP spent the Vote 1 portion of their allocated budgets, but were unable to fully disburse the Vote 10 allocation during the last few years of the evaluation period. The Project Initiation Authorization process (PIA) introduced at GAC in 2011 adversely impacted the delivery of the Gs&Cs programs in the department, including the Capacity Building programs. The PIA process not only reduced the overall efficiency and effectiveness of the programs, but also rendered some planning functions and the role of the governance committees less meaningful. A number of other factors, specifically related to the delivery of the CPBs have additionally limited their effectiveness. For example, delays in the delivery of equipment limited the effectiveness and impact of some training in the field.

The overall project management by IGC staff was good; however the performance measurement systems and practices put in place were deemed not adequate. The CPBs did not have a project database, which impacted the overall information management. ACCBP, CTCBP, Sahel and HSE did not integrate a gender perspective in their programming. The Capacity Building Programs used an appropriate mix of delivery channels by working through OGDs, multilateral agencies, trilateral mechanisms and partnerships with Canada’s allies. ACCBP, CTCBP and HSE generally coordinated their security programming well with other donor countries through bilateral consultation and regional organizations.

Recommendations

It is recommended that ACCBP and CTCBP:

- Focus on long-term capacity building by continuing to support multi-year projects (or a series of shorter-term projects with mutually reinforcing outcomes) within target regions/themes to ensure sustainability of results, while earmarking some funding for quick response to emerging needs.

- Increase coordination and synergy with other security programs, and with development programming at GAC.

- Assess efficiency at the program and project levels more systematically.

- Continue improving performance measurement systems and practices at the program and project levels.

- Integrate a gender perspective into program planning, monitoring and reporting.

1.0 Introduction

The Evaluation Division (ZIE) at the Department of Global Affairs Canada (GAC) is housed within the Office of the Inspector General (ZID) and is mandated by Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (TBS) through its 2009 Policy on Evaluation to conduct evaluations of all departmental direct program spending (including grants and contributions) every five years. The Evaluation Division reports to the Departmental Evaluation Committee (DEC) on a quarterly basis, which is chaired by three GAC deputy ministers.

The evaluation of the Anti-Crime Capacity Building Program (ACCBP) and the Counter-Terrorism Capacity Building Program (CTCBP) was conducted according to the requirements of the Transfer Payment Policy (2009) and as part of GAC’s Five Year Evaluation Plan. The target audiences for this evaluation report are GAC’s senior management, program managers, other government departments (OGDs) who partner in the delivery of the programs, as well as the Canadian public.

1.1 Background and Context

The Government of Canada (GoC) plays a fundamental role in protecting the safety and security of Canadians. While strengthening Canada’s domestic response to crime and terrorism remains a priority, Canada’s security is inextricably linked to that of other states, which may lack the resources or expertise to prevent and respond to criminal and terrorist activities. When source and transit states for various criminal and terrorist activities are vulnerable, the security of Canadians and Canadian interests, at home and abroad, is threatened.

The 2008 Speech from the Throne reiterated the fact that Canada’s national security depends on global security, which ultimately depends upon the respect for freedom, democracy, human rights and the rule of law. The achievement of these values across countries is often imperilled by international organized crime and terrorist activities. Such activities place the security, safety and prosperity of Canadians and all global citizens at risk.

The Counter-Terrorism and the Anti-Crime Capacity Building Programs were established to enhance the capacity of states to fight terrorism and transnational organized crime. The beneficiaries of these programs are mainly countries and regions where criminal and terrorist activities originate and/or pass through but do not possess the resources to prevent such activities on their territory; such countries are also referred to as “source” and “transit” countries for criminal or terrorist activities.

CTCBP was created in 2005 with a mandate to provide assistance to foreign states in the form of training, provision of equipment, technical and legal assistance to enhance their capacity to prevent and respond to terrorist activities. Assistance provided by CTCBP is global in coverage and targeted to countries and regions with identified needs. A separate Sahel Program envelope was created in late 2010 for that specific geographic region. This special envelope is managed by CTCBP.

ACCBP was established in December 2009 to enhance the capacity of beneficiary states, government entities and international organizations to prevent and respond to threats posed by transnational criminal activity in the Americas. As of 2015 the ACCBP has a global scope with a focus on the Americas. In 2012, a separate Human Smuggling Envelope (HSE) was announced to address those operations destined for Canada. HSE has a global scope, with a particular focus on Southeast Asia and more recently West Africa. This special envelope is managed by ACCBP.

Both programs represent a whole-of-government approach, drawing on the expertise of other Government of Canada departments (OGDs) and agencies to effectively deliver security capacity building to beneficiary states and ensure that these states are better able to manage and respond to security threats. These programs also aim to contribute to Canada’s national security and other Canadian interests, such as the safety of Canadians abroad, the provision of a more stable environment for Canadian commerce and trade to operate internationally, as well as to Canada’s international reputation and influence.

In 2008-2009, GAC reviewed its approach to programming aimed at preventing criminal and terrorist activities as a result of a number of factors, such as the expiration of the CTCBP’s Terms and Conditions in March 2010; the approval of an allotment from the International Assistance Envelope (IAE) for a program to build anti-crime capacity; and recommendations of a formative evaluation of CTCBP, etc. GAC opted for an approach that harmonized the management and delivery mechanisms for the two capacity-building programs, including the Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs), the Priority Review, the mandate of the Interdepartmental Steering Committee, as well as the existing Annual Voluntary Contributions to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) and the Organization of the American States (OAS) Inter-American Drug Abuse Control Commission (CICAD).

ACCBP and CTCBP are managed by GAC’s Capacity Building Programs Division (IGC) in the Non-Proliferation and Security Threat Reduction Bureau (IGD) of the International Security and Crisis Response Branch (IFM). Although ACCBP and CTCBP have different geographic scopes and activities, they share governance and administration structures and have similar objectives. They will therefore be reviewed and evaluated in parallel in order to identify each program’s respective strengths and weaknesses.

1.2 CTCBP and ACCBP Overview

1.2.1 Program Objectives, Expected Results and Key Activities

The overarching mandate of ACCBP and CTCBP is to enhance the capacity of key beneficiary states, government entities and international organizations to prevent and respond to threats posed by international criminal and terrorist activity. The programs achieve this by providing transfer payment assistance through projects and initiatives, such as: needs assessments, training, legislative drafting and advice, placements of technical experts, equipment and associated material, outreach and advocacy, and operational activities. All programming activities are implemented in line with international obligations, standards and norms. The programs are also expected to contribute to an increased Canadian expertise, influence and leadership in supporting and enabling security capacity building assistance on an international scale.

ACCBP and CTCBP aim to achieve the following immediate outcomes:

- Personnel in beneficiary states and organizations are more knowledgeable and skilled in anti-crime and counter-terrorism policies, procedures and enforcement;

- New or improved anti-crime and counter-terrorism legal instruments, controls and frameworks; and

- Additional or improved anti-crime and counter-terrorism tools, equipment, networks and physical infrastructure are available and in use.

ACCBP’s and CTCBP’s expected intermediate outcomes are:

- Strengthened incident prevention, mitigation and operational readiness and responsiveness;

- Increased compliance with international anti-crime and counter-terrorism commitments; and

- Strengthened infrastructure to support anti-crime and counter-terrorism coordination and response systems.

The expected long-term (ultimate) outcomes are:

- Improved global prevention and response to threats of terrorism and transnational organized crime impacting Canada and Canadian interests.

ACCBP and CTCBP are grants and contributions (Gs&Cs) programs. The G&Cs disbursed by ACCBP and CTCBP are used for a number of activities, such as:

- Needs assessments, data collection and analysis

- Training workshops, seminars and other forms of technical instruction;

- Placement or deployment of experts (in recipient/beneficiary states);

- Legal support;

- Provision of tools, technology and equipment; and

- Physical infrastructure support

- Outreach, advocacy, prevention and awareness raising.

ACCBP and CTCBP achieve their objectives by implementing projects through four delivery mechanisms: bilateral, multilateral, trilateral and partnership programming (see section 4.5.12).

1.2.2 CTCBP

Since CTCBP was created in 2005, the threats posed by international terrorism networks have become increasingly complex, partly in response to international efforts toward their elimination. As a result, the scope and demand for resources and international assistance to build capacity to counter terrorism have increased, along with the pressures to explore the linkages between criminal activities that fund or advance acts of terrorism.

The Counter-Terrorism Capacity Building Program was established in 2005 as an international security assistance mechanism and a key part of Canada’s international terrorism prevention efforts. CTCBP’s mandate is to provide assistance to foreign states that lack the resources and expertise to prevent and respond to terrorist activity in a manner consistent with international norms, standards and obligations. The Program fulfills this mandate through the provision of training, equipment, technical and legal assistance. CTCBP is focused on six key thematic areas, as summarized below.

| Thematic Areas | Activities |

|---|---|

| Border and Transportation Security | Technical assistance to secure points of entry and transportation systems. |

| Legislative Assistance | Assistance to strengthen the legal frameworks against terrorism in States lacking the capacity to do so on their own. |

| Law Enforcement, Security, Military &Intelligence (LEMI) | Technical assistance to police, armed forces and intelligence agencies. |

| Combating the Financing of Terrorism (CFT) | Assistance to enhance the capacity of States to collect, analyse and action financial intelligence related to terrorist activity. |

| Critical Infrastructure Protection | Support to enhance the capacity of States to protect energy, communications, cyber and other critical infrastructure. |

| Countering Improvised Explosive Devices (C-IED) | Policy, training, and equipment interventions to enhance C-IED prevention, mitigation, preparedness, response and recovery. |

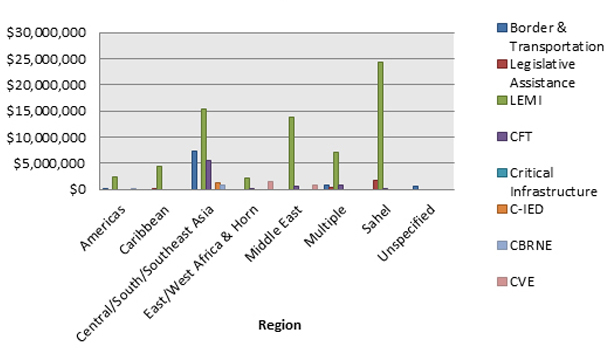

Since CTCBP was established, it has funded more than 229 projects with a total value of over $90 M. During the evaluation period, the majority of CTCBP funding went to LEMI (76%), followed by border and transportation security (10%), as summarized below.

CTCBP Sahel Envelope

In response to the deteriorating security situation in the Sahel region of Africa and increasing threats from Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), the international security donor community (including Canada, the US, France and the EU) set out to strengthen and coordinate international efforts to build regional civilian capacity to combat terrorism. As part of this international effort, and to mitigate the threats to the security of Canadians and Canadian businesses in the region, the Government of Canada provided the CTCBP with an additional $42.5 million for a period of five years (2010-2015) to address terrorist threats in the Sahel. Footnote 1

The relevance and performance of the CTCBP Sahel Envelope were assessed in a separate evaluation and are not covered in this report.

Figure 1: CTCBP Theme Funding by Geographic Area, 2011-2015

Americas Caribbean Central/South/Southeast Asia East/West Africa & Horn Middle East Multiple Sahel UnspecifiedText version

1.2.3 ACCBP

Drug trafficking, organized crime, and related violence and corruption present challenges for governments around the world and threaten Canada’s security and interests. Underlying social conditions and the lack of governance capacity in some countries inhibit efforts to improve security. Persistent poverty, inequality, and unemployment leave large proportions of the population susceptible to crime. At the same time, underfunded security/police forces and failure to fully implement post-conflict institutional reforms render the security sector weak and susceptible to corruption.

Preventing and countering crime, drug trafficking, corruption and money laundering protects Canadian communities and businesses, and reinforces the rule of law on a global scale.

In December 2009, the Government of Canada established ACCBP with the purpose of enhancing the capacity of states, government entities and international organizations to prevent and respond to threats posed by transnational criminal activity. The program was created specifically to address national, regional and international security threats posed by criminal activities such as drug and firearms trafficking, money laundering, corruption, human smuggling and urban gang violence in the Americas.

Program activities and initiatives are implemented under six thematic areas:

| Thematic Areas | Activities |

|---|---|

| Illicit Drugs | Support for initiatives designed to address the supply of, and demand for, illicit drugs. |

| Corruption | Support for anti-corruption and transparency measures and assistance for the implementation of legislative frameworks such as the UN Convention against Corruption and the Inter-American Convention against Corruption. |

| Human Trafficking and Migrant Smuggling | Support for the prevention of trafficking in persons, the protection of victims, prosecution of offenders and promotion of partnerships. |

| Money laundering and Proceeds of Crime | Support for anti-money laundering measures and assisting in the effective implementation of regional and international instruments and other accepted standards. |

| Security System Reform | Support for initiatives aimed at increasing the efficiency and effectiveness of defence, police, judicial, intelligence and prison sectors to combat and prevent criminal activity. |

| Crime Prevention | Support for initiatives aimed at promoting community safety and crime prevention at the national or transnational level. |

Human Smuggling Envelope

In November 2012, the Prime Minister of Canada announced an additional funding envelope of $12M over 2 years (FY2011/12-FY 2012/13) aimed at preventing human smuggling operations abroad. The mandate of the ACCBP-HSE is to provide capacity-building assistance, mainly in the form of training and equipment, to assist beneficiary States in Southeast Asia with the detection and prevention of human smuggling operations destined for Canada. Some HSE funding was also allocated to West Africa, where some specific marine human smuggling threats to Canada were identified.

In response to the continued threat posed by human smuggling ventures to Canada, the program authorities were renewed in 2013 for another two years (FY 2013/14 - FY 2014-2015).

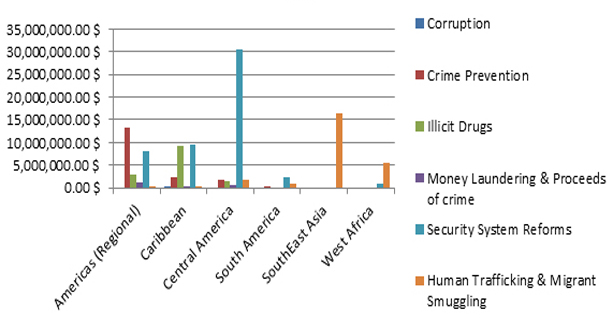

Funding for ACCBP is allocated to individual projects. As of 2009, 191 projects with a total value of $76M have been implemented by the Program in the Americas and the Caribbean.Footnote 2 Under the ACCBP-HSE, 55 projects were implemented during the evaluation reference period with a total value of $22M, the majority of which have been in Southeast Asia. The table below summarizes ACCBP funding by theme, including the HSE projects.Footnote 3

Figure : ACCBP Funding by theme and Geographic Area

Americas (Regional) Caribbean Central America South America South East Asia West AfricaText version

1.3 Governance

ACCBP and CTCBP share a common governance structure, which consists of the following entities:

Interdepartmental Steering Committee

The Interdepartmental Steering Committee (ISC) ensures that both programs are aligned with government-wide priorities for effective global security (anti-crime and counter-terrorism) capacity building. Other federal departments and agencies with a direct mandate to address international crime and terrorism can designate one Director General-level (or equivalent) representative as a member of the Steering Committee.

ISC members contribute to discussions and exchanges on GoC priorities based on their departmental mandates and emerging international trends. Committee members also contribute to setting strategic policy directions for the two programs (both geographic and thematic). They also review and make recommendations to the Annual Strategic Plans and Annual Reports.

The ISC contributes to the strategic direction for CTCBP, and ACCBP funding envelopes. It does not, however, have a mandate to address the ACCBP Human Smuggling Envelope, nor does it provide strategic direction for the Annual Voluntary Contributions (AVCs) to the UNODC and OAS, which are managed by the ACCBP and the CTCBP Secretariats.

ACCBP and CTCBP Project Review Committees

The Steering Committee is supported by the Project Review Committees (PRC) for each program, which in turn are responsible for reviewingFootnote 4project proposals and providing input on projects within their respective subject matter areas of expertise. Other government departments with a direct or indirect mandate to address international crime can designate one representative at the deputy-director level (or equivalent) to the ACCBP Review Committee. Departments with direct or indirect mandate to address international terrorism can respectively designate one representative at the deputy-director level (or equivalent) to the CTCBP Review Committee, which also reviews the proposals for the Sahel envelope. The review committees do not, however, include the ACCBP Human Smuggling Envelope or the AVCs, both being managed by the ACCBP and the CTCBP Secretariats and having distinct governance structures.

The ACCBP and CTCBP review committees are chaired by the Director for the Capacity Building Programs Division (IGC), and is supported by the Chief of each Program.

Capacity Building Programs Division

The Capacity Building Programs Division (IGC) is responsible for the day-to-day program management and reporting. The Capacity Building Programs Division is led by a director and includes a staff complement of 19 FTEs. The Chiefs of Program (equivalent to a Deputy Director) report to the Director of the Capacity Building Programs Division and are responsible for the day-to-day financial and human resources management of the programs. The Division also supports the Project Review Committee for each program and the Chair of the Steering Committee to deliver the Steering Committee’s strategic mandate.

1.4 Program Resources

CTCBP Resources

CTCBP has an approved budget of $13 million per year (ongoing). Of that total, $2.5M is allocated for Vote 1 (Operations and OGD) and $10.4M for Vote 10 (Grants and Contributions).Footnote 5In addition, CTCBP includes $42.5 million for the Sahel Envelope (2010-2015).

ACCBP Resources

ACCBP has an approved budget of $15 million per year (ongoing). Of that total, $2.3M is allocated for Vote 1 and $12.6M for Vote 10. ACCBP also includes the Human Smuggling Envelope (HSE) that had a four-year (2011-2015) budget of $24 million, of which $3.8M is allocated to Vote 1 and $20.2 M to Vote 10.

2.0 Evaluation Objectives and Scope

2.1 Evaluation Objectives

In accordance with the TB Policy on Evaluation, the Summative Evaluation of the Anti-Crime and Counter-Terrorism Capacity Building Programs aimed to assess results achieved to date by both ACCBP and CTCBP and provide GAC’s Senior management with a neutral evidence-based assessment of the relevance and performance of these programs.

The two programs were evaluated in parallel, with a special focus on the results achieved by each program and the extent to which the specific design and delivery approaches of each program supported their efficient and effective implementation. The parallel evaluation assessed synergies between the two programs with respect to their strengths and areas for improvement. Through a systematic data collection process, the evaluation reviewed the achievements of each program, as well as any outstanding gaps and/or areas for improvement. Based on the analysis of the collected data and information and the main evaluation findings, specific conclusions and recommendations were derived pertaining to the relevance and performance of ACCBP and CTCBP. Lessons and opportunities for improvement were also identified to guide future projects and activities under each program.

The specific objectives of the evaluation were:

- To evaluate the relevance of ACCBP and CTCBP by assessing the extent to which they address the needs of the department and its clients, and are aligned with federal government priorities and GAC’s strategic outcomes;

- To evaluate the performance of ACCBP and CTCBP in achieving their expected outcomes efficiently and economically;

- To examine synergies between ACCBP and CTCBP, as well as with other security-related programs, such as GPP and GPSF, and identify complementarities and potential duplications;

- To reflect on the lessons learned from the management and implementation of each program and make recommendations for improved management and delivery of the capacity building projects and initiatives; and

- To review the link between policy and programming in the IFM Branch and the extent to which policy priorities have been reflected in the design of the capacity building programs, as well as how programming results inform policy considerations.

2.2 Evaluation Scope

The evaluation focused on programming developed over the last five years, i.e. from FY 2010-2011 to FY 2014-2015. The evaluation also followed up on the recommendations from the 2009 formative evaluation of CTCBP, and the 2012 formative evaluation of ACCBP.

3.0 Evaluation Approach & Methodology

3.1 Evaluation Design

The evaluation was designed to assess five key evaluation questions:

- Continued need for the program

- Alignment with government priorities

- Consistency with Federal roles and responsibilities

- Achievement of expected outcomes

- Demonstration of efficiency and economy.

The evaluation was guided by an Evaluation Advisory Committee comprised of ACCBP Footnote 6and CTCBP program staff, staff from other related GAC divisions and representatives of other government departments. The Evaluation Advisory Committee reviewed the Evaluation Work Plan, participated in a presentation to validate the evaluation preliminary findings and reviewed the draft evaluation report.

3.2 Approach and Methodology

To ensure a systematic evidence-based process for data collection and analysis, the evaluation employed a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods and multiple lines of inquiry. Qualitative methods including stakeholder interviews, document and project file review, and observation through site visits were used to respond to all of the evaluation issues. These methods were complemented by quantitative methods to assess administrative data and other program information. The available data from various sources was triangulated to identify trends, similarities and points of convergence in order to develop the evaluation findings.

3.3 Evaluation Matrix

An evaluation matrix was developed as part of the Evaluation Work Plan to act as a framework for the evaluation process. It was used to guide data collection and facilitate analysis and the development of findings and recommendations. The matrix outlined the key questions to be answered by the evaluation as well as the related performance indicators, data sources and data collection techniques. (See Appendix [7])

3.4 Data Collection Methods

3.4.1 Primary Data Collection

Key Informant Interviews

A total of 175 key informants were interviewed for the evaluation in Ottawa and during field visits. In Ottawa, evaluators interviewed 38 key informants including current or past staff of ACCBP or CTCBP (n=13), other GAC staff at headquarters (n=12), representatives of other government departments (n=13). The interviews assisted evaluators in analysing performance of ACCBP and CTCBP and identifying key issues and areas for improvement.

Site Visits

The evaluators conducted site visits to observe project implementation and meet with implementing organizations, project partners and beneficiaries in eleven countries (Colombia, France, Guatemala, Indonesia, Jamaica, Jordan, Malaysia, Mauritania, Singapore, Thailand, and Trinidad). During those field visits, 137 key informants were interviewed including Mission staff working for GAC (n=18), other Canadian government departments (n=9), and representatives of recipients, implementing partners, allied countries and other local experts (n=110). Evaluators also attended a Steering Committee meeting for the regional UNODC Container Control Program in Thailand. The field visits focused mainly on relevance and program effectiveness.

3.4.2 Secondary Data Collection

Document Review

Evaluators reviewed pertinent documents and literature to assess the relevance and performance of ACCBP and CTCBP. These included GAC corporate documents, descriptive and analytical reports, previous program evaluations, progress reports, and relevant planning, policy and priority review documents. Evaluators also reviewed international studies pertaining to global and regional crime and terrorism to assess the effectiveness of capacity building programming, and the relevance and continued need for ACCBP and CTCBP.

Project File Review

Evaluators conducted a file review of 40 projects Footnote 7to assess the extent to which ACCBP and CTCBP were achieving their expected outcomes in a cost-effective manner. The project sample selection was based on the following criteria:

- distribution among program areas and across geographic regions

- materiality (dollar value)

- implementing methods and partners

- status (completed or in progress)

- duration (one or multi-year).

The project sample was prepared in consultation with the ACCBP and CTCBP Secretariats. (See the project sample list in Appendix [3].)

3.5 Limitations to Methodology

The evaluation team used mitigating strategies to address methodological challenges or limitations, as summarized below.

| Evaluation Challenges | Mitigating Strategies |

|---|---|

| The lack of a project database made it harder to gather information for the project sample. | The evaluation team collected project reports and documents from different electronic sources and IGC managers. |

| Limited results reporting at the project and program levels made it difficult to assess overall impacts. | Evaluators gathered information on project results through interviews and observation during field visits, but only for a limited number of projects. |

| The attribution of results to ACCBP or CTCBP was challenging given that other donors, and/or factors, could have contributed to outcomes. | The evaluation team used a contribution analysis approach to assess the relative/relevant contribution from ACCBP and CTCBP. |

| ACCBP, HSE and CTCBP covered a wide geographic area (all regions). | The evaluators conducted field missions to 11 countries in four regions to gather representative data. |

| ACCBP, HSE and CTCBP addressed a wide range of issues. | Each program was assessed separately, and then findings were compiled into the overall evaluation report. |

4.0 Evaluation Findings

The following findings are based on the triangulation of evidence from relevant literature, project documents, project file reviews, key informant interviews and observation during site visits.

4.1 Relevance Issue 1: Continued Need for the Programs

Finding #1: The evolving nature of the threats posed by international terrorist networks and their increasing frequency and severity require governments to develop respective programs, initiatives and strategies to counter these threats. CTCBP, ACCBP and HSE continue to be a relevant GoC response to these threats and to effectively adapt to the changing needs related to the fight against international crime and terrorism.

Based on evidence from interviews, site visits and document review, CTCBP and ACCBP (including HSE) continue to be relevant and adapt well to changing needs or threats related to international crime and terrorism. The relevance and evolution of each Capacity Building ProgramFootnote8(CBP) is assessed separately below.

4.1.1 Counter-Terrorism Capacity Building Program

During the evaluation period, half of CTCBP’s programming (excluding the Sahel Program) was in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), and Asia.Footnote 9Given that geographic focus, the section below highlights the main security needs or threats that CTCBP aimed to address in those regions.

Middle East and North Africa

The threats posed by international terrorism networks increased in frequency and severity over the last few years. Recent attacks in North America and Europe revealed the danger that violent extremists pose to any country. The rise of ISIS in the Middle East demonstrated the continued ability of terrorist groups to expand rapidly and recruit globally. The conflict in Iraq and Syria attracted Foreign Terrorist Fighters (FTFs), particularly from the MENA region, into the ranks of ISIS and other armed terrorist groups. Many countries lacked the laws, immigration system or border security necessary to control the flow of FTFs. Thus controlling FTFs was among the highest global security concerns for Western governments and destination countries. A related global priority was Countering Violent Extremism (CVE) through policies to discourage recruitment and improve outreach in communities at risk.

CTCBP programming focused on blocking the transnational transit routes of FTFs, and countering financing of terrorism (CFT). The Program started CVE projects in 2014-2015, in response to the increased need to prevent recruitment, and rehabilitate returned fighters.

Asia

Some countries in South Asia, e.g. Afghanistan and Pakistan, have faced an ongoing Taliban insurgency that has threatened the region’s stability. Central Asia was a source and transit region for violent extremists who went to join ISIS and other groups. CTCBP had significant programming in Afghanistan that focused on bilateral security training, although that decreased following the military and political drawdown in 2012.

Southeast Asia has been threatened by violent extremism from separatist insurgencies, particularly in the Philippines, Malaysia and Indonesia. CTCBP programming there contributed to building the skills of law enforcement officers, Countering Improvised Explosive Devices (C-IED), supporting INTERPOL’s counter-terrorism activities, and combating the financing of terrorism

Assessment of Continued Relevance of CTCBP

All 15 CTCBP projects reviewed during the evaluation showed evidence that they responded to the needs of beneficiary states. Twelve projects provided data on how they identified and responded to potential security threats to Canada, while the other three did not explain that explicitly.

Evidence from interviews and project documents showed that CTCBP analyzed and responded to emerging security needs well. For example, CTCBP partners identified Middle Eastern financial institutions as a potential source of terrorist funding in 2010, a few years before that issue became prominent within the anti-ISIS coalition. Responding to the increased threat posed by ISIS at the regional and global levels, CTCBP introduced FTF and CVE programming in 2014, and increased programming in Iraq and Jordan.

4.1.2 Anti-Crime Capacity Building Program

During the evaluation period, more than 70% of ACCBP’s programming was in Central America and the Caribbean, with the remainder being spent in South America and Mexico. Given that geographic focus, the section below highlights the main security needs or threats that ACCBP aimed to address in Central America and the Caribbean.

Central America

The impact of illicit drug trafficking increased in Central America over the last several years as transnational criminal organizations transferred production operations there from South America and Mexico. The security situation was worst in the Northern Triangle (Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador), which had the highest violence and homicide rates in the world, along with the lowest levels of criminal prosecution and conviction. The illicit drug trade drove related issues such as increasing levels of corruption and money laundering. Illegal trafficking in persons became an area of expanding operations and profit for transnational criminal organizations. Unaccompanied child migration was another emerging concern.

ACCBP programming in Central America focused on security sector reform (including reduced impunity and corruption), and combating illicit drug trafficking. The Program also started to fund projects related to unaccompanied child migration.

The Caribbean

The Caribbean faced several security-related problems during the evaluation period. As a transit region for illicit drug trafficking from the Andean region to Europe, the Caribbean had high rates of criminality and violence. Its financial institutions faced the risk of being used for money laundering and terrorist financing. National and regional security institutions had relatively low capacity and little coordination.

ACCBP programming in the Caribbean covered security and justice reform, combating illicit drugs, anti-corruption and anti-money laundering. ACCBP focused on building the capacity of counterparts in Jamaica and Trinidad & Tobago, which could serve as regional hubs for expertise.

Assessment of Continued Relevance of ACCBP

All of the 12 ACCBP projects reviewed during the evaluation showed evidence that they responded to the needs of beneficiary states. Eight of the projects documented evidence that they identified and responded to potential security threats to Canada.

Evidence from interviews and project documents showed that ACCBP adapted well to changing security needs. Two examples of this were:

- ACCBP shifted its resources from Mexico and South America in 2011-2012. The Program focused on Central America as it went from being primarily a transit region to a production source, with increased rates of violence and corruption. Within Central America, ACCBP concentrated on the Northern Triangle where transnational criminal activity was worst.

- Since ACCBP was established in 2009, transnational organized crime (e.g. money laundering, trafficking of persons) has become even more globalized. In response to globalized threats, the ACCBP’s Terms and Conditions were changed in April 2015 to allow programming outside the Americas. The first new projects approved were for border security in Ukraine and police reform in the Philippines.

A few interviewees questioned whether ACCBP projects were always based on real needs identified by recipient partners. In a few cases where an OGD wanted to deliver a standard course, training seemed to be more driven by supply (OGD interest in delivering the course) rather than demand.

4.1.3 Human Smuggling Envelope

Every year, hundreds of thousands of migrants are moved illegally by highly organized international smuggling and trafficking groups. This growing global threat is often linked to other criminal activities such as money laundering, corruption, drug and arms trafficking. Canada was targeted as a destination country, with hundreds of illegal migrants arriving by boat in 2009-2010.

HSE programming contributed to curbing the flow of illegal migrants by providing different levels of training and specialized equipment to over 6,000 immigration and law enforcement officers. HSE projects focused on countries that were, or were likely to become, transit points for boat smuggling operations to Canada, notably Southeast Asia and West Africa.

Assessment of Continued Relevance of HSE

Of the 13 HSE projects reviewed during the evaluation, 12 had evidence on file of the need in beneficiary states. Only one project did not have adequate documentation to demonstrate beneficiary need. However all 13 projects provided evidence that they identified and responded to threats to Canada.

Evidence from interviews and project documents showed that HSE adapted well to changing needs and priorities. For example, HSE provided support to partners in West Africa when human smuggling operations spread there from Southeast Asia.

4.2 Relevance Issue 2: Alignment with Government Priorities and Other GAC Programs

Finding #2: CTCBP, ACCBP and HSE align with GoC foreign policy priorities, Canada’s Counter-Terrorism Strategy, as well as other whole-of-government and GAC policies and strategies.

4.2.1 Counter-Terrorism Capacity Building Program

Canada’s Counter-Terrorism StrategyFootnote 10outlined the roles and responsibilities of each Department. One of GAC’s responsibilities was to “use its broad international network to enable counter-terrorism co-operation with other states and its role within multilateral organizations to enhance the security of Canadians and Canadian interests”. CTCBP contributed to implementing that Strategy by building national and regional capacity to counter financing of terrorism, foreign terrorist fighters, and violent extremism in the most vulnerable regions in the world (Middle East and Asia).

4.2.2 Anti-Crime Capacity Building Program

One of the objectives of Canada’s Strategy for Engagement in the AmericasFootnote11is “supporting efforts to improve security, especially in Central America, Mexico and the Caribbean”. ACCBP was a key element of that security pillar. The Program aimed to promote justice, security, peace and human rights; prevent violence, crime and corruption; and combat transnational organized crime, including drug trafficking.

4.2.3 ACCBP Human Smuggling Envelope

Canada’s Migrant Smuggling Prevention Strategy was put in place in 2010 as a response to the arrival of two human smuggling vessels on the West Coast. HSE contributed to implementing the Strategy by helping to prevent irregular migration through training and the delivery of specialized equipment for immigration and law enforcement officers in countries that were likely to be transit points for human smuggling operations destined for Canada.

Finding #3: While there is evidence of increased consultations and information sharing among GAC’s security and development programs, the coordination and collaboration with regard to planning and program implementation can be further increased.

Consultation between ACCBP and CTCBP

The evaluation found good coordination between ACCBP and CTCBP because they had:

- joint governance bodies (ISC, PRC).

- regular exchanges between program staff that helped reduce duplication, which were easier because ACCBP and CTCBP were housed in the same Division (IGC)

- some flow of project officers between the two Programs.

- the same Standard Operating Procedures and project management tools.

ACCBP and CTCBP programming is under one Director General (DG) (IGD), while crime and terrorism policy work is handled by a division (IDT) reporting to a different DG (IDD). That split required staff to make concerted efforts to align programming and policy. According to GAC staff, IDT and IGC staff consulted regularly at the working level and prepared joint briefing notes. Regular IDT-IGC management meetings are held but there was less coordination at the DG-level.. In some cases, coordination in the field was reported to be better than at HQ.

GAC staff noted a few cases of thematic or geographic overlap between ACCBP, HSE and CTCBP projects. For example, the financing of terrorism (CTCBP) and money laundering (ACCBP) were overlapping issues. There was some fluidity of projects between the two programs. For example, an OAS critical infrastructure project was first funded under CTCBP, and then transferred to ACCBP. ACCBP had a sub-theme of human smuggling, although its projects were limited to the Americas, while HSE focused on Southeast Asia. Some implementing partners reported uncertainty about whether to submit proposals to CTCBP or ACCBP because the criteria or boundaries for each were not clear.

Coherence with other Security Programs and Other Divisions

The evaluation found that there was less coherence between ACCBP-CTCBP and other GAC security programs. GAC’s International Security Branch (IFM) funds security-related initiatives through seven programming channels (programs and envelopes), as outlined below.

| Program | Focus | Annual Budget $ M * |

|---|---|---|

| * This column shows the annual average budget during the evaluation period. | ||

| Anti-Crime Capacity Building Program (ACCBP) |

| 15.0 |

| Human Smuggling Envelope (HSE) |

| 6.0 |

| Counter-Terrorism Capacity Building Program (CTCBP) |

| 13.0 |

| Sahel Envelope |

| 8.5 |

| Global Partnership Program (GPP) |

| 73.4 |

| Global Peace & Security Fund (GPSF) |

| 108.0 |

| Annual Voluntary Contributions (AVCs) |

| 3.45 |

The security programs (CTCBP, ACCBP, GPSF and GPP) were designed at different times to support GoC policy initiatives that emerged independently. The programs were not planned as a cohesive or integrated package, which created challenges for communication and coordination. Stakeholders interviewed during the evaluation noted that GAC took steps to improve coherence among its security programs, however there were still limitations, as summarized in the table below.

| Steps Taken to Improve | Remaining Limitations |

|---|---|

Structural

| Structural

|

Procedural

| Procedural

|

The steps taken helped increase communication among security programs, however some GAC staff told evaluators that there was still some confusion of roles between different corporate units. According to staff, policy and programming shops were in separate “silos”; and each security program was in its own silo. Coherence among security programs needs to be solidified and systematized.

Based on evidence from interviews and document review, the greatest potential overlap (and opportunity for coordination) of security programming was between ACCBP/CTCBP and GPSF because of their similar thematic coverage and focus on capacity building. For example, all three programs provided support for capacity building in Colombia. Those programs overlap with some areas of GAC’s development cooperation in Colombia as well (see Table 6 below).

According to interviews at HQ and in the field, ACCBP and CTCBP staff regularly consult the geographic branches; however the capacity building programs, geographic branches and OGD HQs in Ottawa had a mixed record in engaging Missions. GAC staff at some Missions reported that they were actively involved in the selection of ACCBP/CTCBP projects, while OGD representatives at some missions indicated that they were not always consulted on security programming by their HQs, even when they might have had relevant expertise and better knowledge of the situation and partners in the field.

Coordination with Development Programming

With the amalgamation of DFAIT and CIDA in 2013, coordination between ACCBP/CTCBP and development programming became a higher priority and created a challenge for the security programs. There were several possible areas of overlap (and/or complementarity) between GAC’s security and development programming. For example, ACCBP, GPSF and development programs all supported capacity building projects to combat corruption. Anti-crime activities in Ukraine were funded through GPSFFootnote12, ACCBP (starting in 2015) and development cooperation. Projects dealing with human smuggling or trafficking were funded by HSE (criminal justice and law enforcement in Asia); ACCBP (criminal justice, law enforcement, border control in the Americas); GPSF (justice, security, reintegration of victims); and development programs (law enforcement, trafficking prevention).

That potential overlap (and/or synergy) was seen in countries or regions visited by the evaluation team, as illustrated in Colombia example below.

| Program | Issues Funded by Projects |

|---|---|

| ACCBP |

|

| CTCBP |

|

| GPSF |

|

| GPP |

|

| Development |

|

In the case of Colombia, stakeholders noted that coordination was quite good between ACCBP/HSE/CTCBP and development cooperation. GAC developed an integrated Country Strategy (2015) that included development and security programming and policy engagement in Colombia. Security and development programs worked well together in several African countries as well, according to CTCBP staff.

The evaluation mission to Guatemala found evidence of the complexities of coordination between ACCBP and other security programming there:

- development funding instead of ACCBP: ACCBP (or GPSF) planned to support the International Commission against Impunity (CICIG), however it could not provide the level of funding ($5M) over the longer-term period (three years) that was required. CICIG was passed to the development program for funding, even though it did not fit in the sectors outlined in GAC’s Development Country Strategy for Guatemala.

- complementary funding from both ACCBP and development: The development side had supported the Justice Education Society (JES) since 1999 to build the anti-crime capacity of police and public prosecutors in Guatemala. ACCBP provided complementary funding to JES starting in 2011, and then became the main GAC partner

- overlapping, uncoordinated funding from ACCBP and development: Through CICIG, GAC-DEV supported capacity building of the Public Prosecutor’s Office, which also received funding from an ACCBP project. Having two separate projects with different GAC managers created confusion for Guatemalan partners, who wondered why Canada had “two cooperation sections” at the Embassy.

GAC staff interviewed during the evaluation suggested that security and development programming each have comparative advantages that could be combined in a coherent and complementary package, as illustrated in Table 7 below.

| Issue | ACCBP/CTCBP (Security) | Development |

|---|---|---|

| Thematic Focus | “Hard” security issues (e.g. training and equipping security and police forces; transnational organized crime). | “Soft” security issues (e.g. improved governance, elections, anti-corruption) (currently covered by GPSF as well). |

| Duration | Shorter-term initiatives (1-3 years) that require quicker funding. | Longer-term projects (5-10 years)with expected intermediate outcomes. |

| Size | Smaller projects (as determined by funding limits of ACCBP/CTCBP). | Larger projects, particularly in countries of focus. |

| Location | Priority countries based on identified needs and threat to Canada. | 25 “countries of focus”, which receive 90% of ODA funding. |

| Implement-ing Agency | Participation of OGDs (Vote 1 funding), as well as international agencies. | Best Canadian or international implementing partner, usually an NGO. |

During the evaluation period, GAC took some steps to improve coordination between ACCBP/CTCBP and development programming; however challenges remained as summarized below.

| Steps Taken to Improve | Remaining Limitations or Challenges |

|---|---|

Institutional

| Institutional

|

Procedural

| Procedural

|

Several GAC staff at HQ and Missions stressed the importance of improving coordination between ACCBP/CTCBP (security programs) and development because:

- Capacity development is a long-term process. Many countries lack the necessary expertise in counter-terrorism and anti-crime to be able to readily assimilate and implement training provided by CTCBP or ACCBP.

- Amalgamation created the opportunity, and necessity, for coherent and coordinated departmental programming.

- Several Canadian and international implementing partners such as INTERPOL or UNODC work with different GAC divisions, and find it hard to manage different sets of departmental management requirements.

- Canada’s development programming is increasingly expected to apply a “security lens” when possible (similar to the USAID model), thus needs to coordinate better with ACCBP/CTCBP and other security programs.

- GAC-DEV programs have significantly larger budgets than ACCBP/CTCBP in some “countries of focus”Footnote13. For example, GAC has 25 people on the ground in Mali, so that Mission (or PSU) could provide valuable support to CTCBP projects. ACCBP/CTCBP should seek ways to leverage and complement those larger development investments.

Within the amalgamated department, there was growing interest in reinforcing “security value chains” in specific regions and countries through coordinated programming in areas such as conflict prevention, rule of law, corruption and human trafficking. GAC staff suggested some steps that could be taken towards the goal of having a “seamlessly coherent Canadian cooperation program,”Footnote14 which are presented in section 6.

4.3 Relevance Issue 3: Consistency with Federal Roles & Responsibilities

Finding #4: GAC is the appropriate department to lead ACCBP and CTCBP, although it could promote better communication among OGDs.

ACCBP and CTCBP are closely aligned with GAC’s international mandate that includes supporting international security and the safety of Canadians abroad. GAC is the appropriate department to manage ACCBP and CTCBP because the programs require negotiation and coordination with governments of recipient and donor states, and multilateral organizations. GAC’s network of international Missions with contacts on the ground provides support to ACCBP and CTCBP projects abroad.

ACCBP and CTCBP projects funded through Vote 1 are delivered by other government departments (OGDs) including the RCMP, DND, CBSA, FINTRAC and CCC. The OGDs are involved in project design and selection through the annual Priority Review, the Inter-departmental Steering Committee ISC), and the Project Review Committee (PRC). Before presenting its project proposals, an OGD often undertakes a Needs Assessment Mission (NAM) to meet partners in the target country or region.

According to staff interviewed at several OGDs (RCMP, FINTRAC, Justice Canada, CBSA), their departmental priorities in international security aligned well with those of ACCBP and CTCBP.

OGD staff in Ottawa and liaison officers in the field who were interviewed indicated that they were not familiar with projects implemented by other departments in the same country or region. Each OGD tended to work with different national partners so they could not cooperate at the operational level. For example, the RCMP worked with national police forces or INTERPOL, while DND trained counterpart armed forces. Some OGDs did not inform GAC field staff of security-related missions or projects in their country.

According to some interviewees, not only was there little connection across departments, some OGDs did not even not coordinate capacity building activities within their own department. There was no whole-of-government or whole-of-department approach to security cooperation.

It would have been useful for OGDs to share information, lessons and good practices from their projects with Canadian government departments working in the same country. As a step towards establishing better communication, CTCBP organized a joint NAM on the issue of Foreign Terrorist Fighters (FTFs) in the Middle East. However CTCBP and ACCBP could do more to build connections among OGDs on security-related programming. Some OGD interviewees suggested that GAC and other OGDs should collaborate to develop a security strategy for each region (e.g. Caribbean) to “synchronize and synergize” activities, work more effectively, and have greater impact.

4.4 Performance Issue 4: Achievement of Expected Outcomes

Finding #5: There is some evidence that ACCBP, HSE and CTCBP are making progress towards expected outcomes. However the programs lacked systems or data to measure intermediate outcomes.

While the evaluation did find some evidence of progress towards expected results, ACCBP and CTCBP lacked a systematic focus on outcomes in both their programming and performance measurement (monitoring, reporting) (see 4.5.8). Evidence from interviews, site visits and project files showed that ACCBP, CTCBP and HSE concentrated on the short-term delivery of outputs such as equipment and training, with more than half (56%) of projects completed in a year or less.

The sections below provide illustrative examples of some key results achieved by projects in each Capacity Building Program. The examples were prepared based on information gathered through the evaluation site visits and the project sample document review. The examples highlight intermediate outcomes where possible, and go beyond the results of an individual project to present aggregate results over time related to a particular issue, implementing partner and/or country.

In order to demonstrate various ways to present project and program outcomes, each example has a different focus. The CTCBP example shows the combined impact that various capacity building projects had in Malaysia. The ACCBP example covers the longer-term results achieved through various projects implemented by the same Canadian and Guatemalan partners. The HSE example illustrates the outcomes of two regional projects to combat human smuggling.

4.4.1 Counter-Terrorism Capacity Building Program

CTCBP contributed to building national and regional capacities to counter terrorism. For example, the results of CTCBP projects in Malaysia are presented in the textbox below.Footnote15

CTCBP funded several projects in Malaysia over the past five years. The RCMP provided training for potential chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, and explosive (CBRN-E) incidents to more than 1,000 Malaysian first responders since 2006. Through train-the-trainer courses, the Southeast Asia Regional Centre for Counter Terrorism (SEARCCT) developed the capacity to deliver CBRN courses to other countries in the region and world. (The second round of training was funded by GPP.) In 2012, CTCBP shifted focus to building investigative, criminal, maritime and aviation capacity for the Royal Malaysia Police (RMP) and Malaysian Maritime Enforcement Agency (MMEA). A CTCBP project with INTERPOL provided training and two boats for the MMEA to conduct maritime interdiction, ensure compliance with maritime regulations, and collect intelligence on criminal and terrorist networks. MMEA contributed funds to further equip the two boats (that took three years to arrive due to problems with CCC). According to MMEA officials interviewed, the boats strengthened its operability in patrolling Malaysia’s waters against drug trafficking, human smuggling, piracy and environmental damage; increased the number of inspections (although the arrest rate was still low); and improved coordination with other maritime agencies such as search and rescue. Malaysia also benefited from three regional CTCBP projects with INTERPOL that covered ten ASEAN countries. The projects trained police officers on intelligence gathering and criminal analysis using INTERPOL tools and services along with their domestic intelligence. Project results included increased investigative resources, specialized forensic capabilities, and improved information sharing among law enforcement agencies of ASEAN member states. The projects also gave Canadian law enforcement agencies an opportunity to utilize INTERPOL’s extensive network to increase their capacity and partnerships in counter terrorism. Canada received high-level recognition from the Government of Malaysia for its contribution to security cooperation through CTCBP, ACCBP and other programs. An indicator of that good relationship was the Memorandum of Understanding that Canada and Malaysia signed in 2013 to expand their cooperation on countering international crime and terrorism through CTCBP, ACCBP and other programs. SEARCCT, which is part of Malaysia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, recognized Canada as its “top partner”. That recognition opened the door to other Ministries, and helped Canada engage with other countries like the UK, US and Australia in the delivery of training. Canada’s good relations with Malaysian counterparts also helped the US get buy-in from local authorities because it coordinated with training provided through the Capacity Building Programs.Footnote16Malaysia: Counter-Terrorism Projects

4.4.2 Anti-Crime Capacity Building Program

ACCBP achieved notable results in combating criminal activity such as drug trafficking, gang-related violence and corruption in Latin America and the Caribbean. Illustrative aggregate results of a series of projects implemented by the same Canadian and Guatemalan partners are highlighted in the textbox below.

The Canadian-based Justice Education Society (JES) began working in Guatemala in 1999 with support from former CIDA (until 2013). Starting in 2011, JES implemented four ACCBP projects in Guatemala. Two training projects ($1.2M) increased the efficiency of criminal investigations, reduced impunity, and improved collaboration between police and prosecutors at the Public Ministry. Two other regional projects ($5M) strengthened the capacity of law enforcement agencies in Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras by providing equipment and training on the use of special investigative techniques such as surveillance, wiretaps and forensic video analysis. Based on interviews in Guatemala and written reportsFootnote17, ACCBP (and former CIDA) projects with JES contributed to the achievement of the following quantitative results between 2009 and 2013: One ACCBP project was implemented in Quetzaltenango, the second largest city in Guatemala. According to the Quetzaltenango District Attorney, Canadian support led to “a significant reduction in the levels of criminality and impunity in Guatemala”. The JES project contributed to the following results in Quetzaltenango: JES worked with the Supreme Court of Justice in Guatemala since 2006. During the evaluation site visit to Guatemala, Court officials reported that the training and equipment provided through JES projects increased the efficiency (reduced backlogs), effectiveness, and security (using videoconferences rather than transporting inmates to court) of the criminal courts. Videoconferencing also increased justice and protection for indigenous groups because witnesses could testify in their regions without having to be moved to Guatemala City. The Court established videoconference facilities across the country, including in remote areas. JES regional projects provided training to more than 2,300 judges, prosecutors, police officers and investigators, with women comprising one-third of participants. The regional projects strengthened relations and cooperation between Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras in law enforcement. El Salvador and Honduras also received some technical assistance from Guatemala, which had more developed legal and justice systems, partly attributable to previous projects funded by ACCBP and GAC-Development. According to GAC staff, “JES gained high-level access within the Attorney General’s office and strong credibility. The JES projects changed how criminal cases were prosecuted in Guatemala, increased public confidence in the justice system, and gave Canada high visibility and strong credibility.” In a 2014 letter to support a proposed ACCBP project, the Guatemalan Attorney General wrote that “JES has worked with us for more than 14 years to strengthen and reform our justice system. The Government of Canada has been a strategic ally [...] in our efforts to combat crime and disarticulate criminal gangs in Guatemala.”Guatemala: Justice Education Society Projects

4.4.3 Human Smuggling Envelope

Over the past four years, programming under the HSE has evolved concurrently with the evolving nature of the threats, and has led to the establishment of reliable partnerships with key beneficiaries, which in turn has helped the Program to better target and address the specific threats to Canada. Close collaboration and coordination with trusted allies such as the U.S., Australia and New Zealand, as well as with international organizations such as the International Organization for Migration (IOM) and the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) have increased Canada’s image in the region as a trusted and reliable partner in preventing human smuggling, in-person trafficking, and illegal migration. Interviews with representatives from like-minded donor countries reiterated the importance of Canada’s efforts in enhancing the capacity of the maritime police and the border and immigration services in the countries of SEA.

Funding through the HSE has, for example, enabled IOM to support the governments in the region to strengthen their document examination capacity to more effectively prevent human smuggling and human trafficking by combatting the use of fraudulent documents as a means through which human smuggling flourishes.

The International Organization for Migration (IOM) is one of the main international partners for CTCBP, ACCBP and particularly HSE. During the evaluation period, the IOM implemented 16 HSE projects in Southeast Asia worth about $5M, of which 13 projects worked in one country only and two regional projects covered six to twelve countries.Footnote18 The two regional projects aimed to combat human smuggling and transnational crime by improving the capacity of frontline immigration and border control officers to detect illegal travel documents and detain the users. The projects provided training to immigration and border agencies to increase their technical capacity and knowledge about potential threats related to identity and document fraud. A “training of trainers” approach was used to build local capacity and sustainability, and promote national and regional cooperation. At the national level, trained trainers in Indonesia and Vietnam delivered the roll-out trainings at local sites. At the regional level, Malaysian trainers delivered the IOM courses in Cambodia and Myanmar. Seven countries received specialized equipment that uses biometric data to detect fraudulent travel documents. As a result, participating countries reported an increase in the number of intercepted documents. Over the last few years (until February 2015), national immigration services intercepted 520 documents that were counterfeit or used by imposters. With support from HSE, IOM established in 2012 a Document Examination Support Center (DESC) based in Thailand. DESC is a “one-stop shop” for immigration and border control officials to get remote assistance and make decisions related to document verification. DESC created the Asian Network for Document Examination, an information-sharing network comprising airport forgery units in ten Southeast Asian and two South Asian countries. According to beneficiaries interviewed during site visits, the IOM projects built national capacity to combat human smuggling and other transnational crime, and strengthened regional cooperation among immigration and border agencies.Southeast Asia: IOM Regional Projects to Combat Human Smuggling

4.4.4 Sustainability of Results

Finding #6: Longer-term capacity building projects tended to have greater potential for sustainability than one-time training.

The evaluators assessed whether the design of capacity building projects contained elements that would support or hinder the sustainability of results after GAC funding ended. Several projects assessed through the site visits or evaluation sample showed signs that results would likely be sustainable. Projects that built capacity and relations with partners over a longer-term were more likely to have sustainable results. That relationship could have been developed through one longer-term project, or a series of short projects designed to develop capacity in an incremental way over time. However it was harder to maintain continuity and momentum with shorter projects, mostly because of the potential time-gap in getting subsequent projects approved (see 4.5.3).

Some ACCBP and CTCBP projects were able to leverage funding, or to use their funding to complement larger initiatives, thus multiplying the impact and increasing the likelihood of results sustainability of the GAC investment. For example, ACCBP anti-corruption projects in Jamaica were coordinated with larger programs supported by the US and the UK. Through ACCBP, the RCMP provided polygraph training and equipment to the Jamaica Constabulary Force (JCF). The projects helped reduce police corruption by firing (but not prosecuting) 500 officers who failed the polygraph test, improve forensic investigation techniques, and build public confidence in the JCF. The projects funded by ACCBP and other donors enabled Jamaica to become a Polygraph Center for Excellence in the Caribbean.

The main factor limiting sustainability was the complex, evolving security situation in some states where ACCBP and CTCBP operated. Changes and challenges on the ground made it hard or impossible to implement (or sustain) a few projects.

Results achieved by some projects would be difficult to sustain without continued funding from GAC. For example, ACCBP was a major funder of the UNODC’s Container Control Program (CCP) in Latin America and the Caribbean. The program aimed to build the capacity of port control units to identify and inspect high-risk freight containers that could contain illicit drugs or other black market goods. The CCP contributed to a large (twenty-fold) increase in the volume of drugs, weapons and other contraband seized by port control in several countries.Footnote19According to a 2013 evaluation,Footnote20the CCP made a significant contribution to “greatly improved security in the supply chain of containerised goods” in the countries where the program operated. However based on interviews done during evaluation site visits, it was difficult to sustain that level of successful results after ACBBP funding stopped because beneficiaries did not have money or inputs to continue applying and improving the training they received.

Several GAC staff and implementing partners also questioned the sustainability of one-time training courses that were not tied into longer-term project activities. According to interviewees, several training workshops and support from senior decision-makers would be required to institutionalize and sustain capacities related to anti-crime and counter-terrorism. That view was supported by evidence from international literature that indicates that short-term activities should contribute to long-term learning and change strategies.Footnote21