Evaluation of the Office of Religious Freedom

Final Report

May 2016

Table of Contents

- Abbreviations, Acronyms and Symbols

- Acknowledgements

- 1.0 Introduction

- 2.0 Evaluation Scope & Objectives

- 3.0 Operational Considerations/Key Considerations

- 4.0 Evaluation Complexity and Strategic Linkages

- 5.0 Evaluation Approach & MEthodology

- 6.0 Limitations of the Evaluation

- 7.0 Management of the Evaluation

- 8.0 Evaluation Findings

- 8.1 Relevance Issue 1: Continued Need for the Program

- 8.2 Relevance Issue 2: Alignment with Government Priorities

- 8.3 Relevance Issue 3: Consistency with Federal Roles & Responsibilities

- 8.4 Performance Issue 4: Achievement of Expected Outcomes

- 8.5 Performance Issue 5: Demonstration of Efficiency & Economy

- 9.0 Conclusions of the Evaluation

- 10.0 Recommendations

- 11.0 Management REsponse and Action Plan

Figures

Abbreviations, Acronyms and Symbols

- ADM

- Assistant Deputy Minister

- APP

- Approved Programming Process

- CFLI

- Canada Fund for Local Initiatives

- CFP

- Call for Proposals

- CFSI

- Canadian Foreign Service Institute

- CIC

- Citizenship and Immigration Canada

- CIDA

- Canadian International Development Agency (former)

- DEC

- Departmental Evaluation Committee

- DFAIT

- Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade (former)

- DFATD

- Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development

- DG

- Director General

- EAC

- Evaluation Advisory Committee

- FPDS

- Foreign Policy and Diplomacy Service

- FTE

- Full Time Employees

- FY

- Fiscal Year

- GAC

- Global Affairs Canada

- GoC

- Government of Canada

- GPSF

- Global Peace and Security Fund

- HoM

- Head of Mission

- ICBP

- Integrated Corporate Business Plan

- ICC

- Interdepartmental Consultative Committee

- IFM

- Assistant Deputy Minister of International Security and Political Affairs (Political Director)

- IRCC

- Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada

- IRF

- International Religious Freedom

- LM

- Logic Model

- MAAT

- Mission Advocacy Activity Tracker

- MFA

- Ministries of Foreign Affairs

- MRAP

- Management Response Action Plan

- NGOs

- Non-governmental organizations

- ODA

- Official Development Assistance

- OGDs

- Other government departments

- OIRF

- Office of International Religious Freedom (United States)

- O/MINA

- Office of the Minister of Foreign Affairs

- OPI

- Office of Primary Interest

- ORF

- Office of Religious Freedom

- PAA

- Program Alignment Architecture

- PIF

- Post Initiative Fund

- PMF

- Performance Management Framework

- PMO

- Prime Minister’s Office

- PMS

- Performance Measurement Strategy

- PS

- Public Safety Canada

- PSC

- Project Selection Committee

- RBM

- Results-Based Management

- RFF

- Religious Freedom Fund

- START

- Stabilization and Reconstruction Task Force

- TBS

- Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat

- USS

- Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs

- ZIE

- Evaluation Division

Acknowledgements

The evaluation team would like to extend its appreciation to the many individuals and organisations who agreed to participate in the interviews both in-person and by telephone, as well as those who provided written comments when an interview was not possible or to augment their input. A number of organisations made particular effort to bring in the expertise that was most pertinent for questions of this evaluation, demonstrating interest in the evaluation and in the Office. The participants included: the Heads of Canadian Diplomatic Missions, FPDS staff at missions, religious leaders in Canadian communities, partner organisations, non-governmental stakeholders domestic and international. Also, we would like to thank public servants from likeminded countries working under the broad theme of freedom of religion or belief, in particular the United States State Department and American experts based in Washington D.C for their time and access to information. The team would also like to acknowledge the advice given by key stakeholders and the efforts of the staff at the Office of Religious Freedom who made themselves readily available for the evaluation.

Executive Summary

In June 2011, the Government of Canada (GoC) made a commitment to create an Office of Religious Freedom to help protect religious minorities and to promote pluralism. The Office of Religious Freedom (ORF), housed within the Department of Global Affairs Canada (GAC) (formerly Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada (DFATD)) opened in February 2013 with the appointment of a Canada-based Ambassador. The Office was uniquely dedicated to freedom of religion or belief as a Canadian foreign policy priority. The mandate of the Office supported the Strategic Outcome of Shaping the International Agenda to Canada’s Benefit and Advantage. To achieve this mandate, a Religious Freedom Fund (RFF) was established within ORF. The RFF financed international projects that assisted religious communities facing intolerance or persecution in a particular country of strategic interest to Canada. The ORF and the $17M Fund had a 4-year mandate from 2012-2013 to 2015-2016. The ORF did not become a fully operational unit until the appointment of the Ambassador for Religious Freedom in February 2013.

This evaluation was conducted between October 2014 and April 2015. In order to capture the most recent 21-month period of ORF’s full operation, the evaluation reference period was from June 2012 to the end of October 2014. The evaluation approach addressed all five core evaluation issues; covered all activities outlined for ORF in governing documents; reached out to a broad spectrum of key stakeholders; employed a mixed methods approach of qualitative and quantitative methods; and, triangulation of multiple data sources. The purpose of the evaluation was to assess whether the Office was on-track in its design, program and policy development, alignment, delivery and activity to achieve expected results.

Key Findings

The evaluation found that ORF was actively engaged and leading on the thematic priority of freedom of religion or belief. The areas of most significant impact and notable success were among the international diplomatic community as well as selected GAC Geographic desks and selected missions of strategic interest. ORF was seen as a focal point that facilitated the ability to advocate on freedom of religion or belief and to raise awareness and the relevance of a subject that is less familiar to traditional topics of diplomacy.

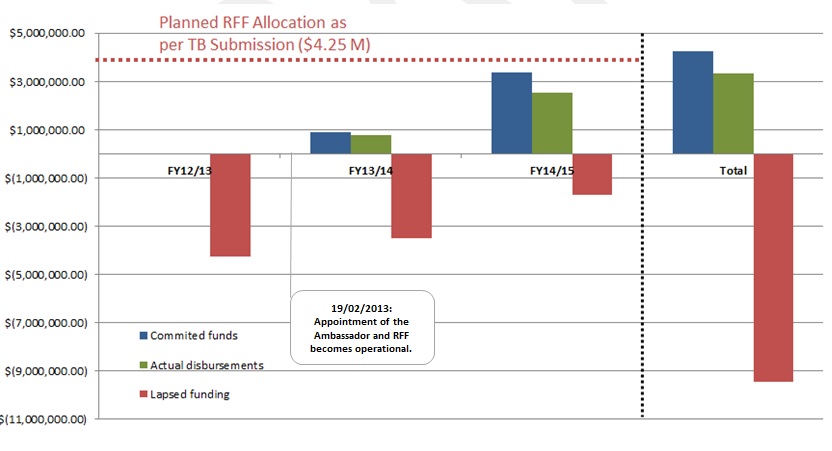

The Office, through RFF, was meeting a need to improve freedom of religion or belief by funding relevant projects on this theme. In doing so, ORF and RFF were aligned to meet GoC priorities and addressed a gap within a specific theme in human rights. The evaluation found that the disbursement of RFF funds was delayed, with a significant amount lapsed due in large part to delays in fully operationalizing the Office. Findings identified a time lag of 8 months from when the ORF’s governing documents were approved to the time that an Ambassador was named on February 19, 2013.

Common to several findings is that the overall awareness of ORF was not uniform. Information-sharing with other key GAC officers, as well as with domestic stakeholders, varied and was sometimes weak for differing reasons. Some relevant GAC officers were not accessing the content necessary to leverage the thematic priority or the Office in their networks. They were not familiar with how ORF was operationalizing its mandate or the RFF. The lack of communication on the RFF made it unclear for external stakeholders and potential recipients to consider applying for the RFF. Meanwhile, domestic outreach was extensive, in particular with bilateral meetings at the launch phase. However, the lack of broader and more consistent sharing of information to the public caused inefficiencies and hindered ORF’s own efforts to ensure the Office was not perceived as favouring any specific group or religion.

Transparent, regular and substantive information to stakeholders in GoC and externally would have strengthened ORF’s leadership as well as allowed for a more accurate appreciation of the Office. Furthermore, consistent efforts in this area could have improved efficiencies and the effectiveness of achieving ORF’s mandate and Canada’s leadership of this priority. The Office was in operation for more than two years. ORF needed to improve its documentation and information-sharing beyond a bilateral approach.

Recommendations

Recommendation #1: It is recommended that the focal point for freedom of religion or belief develops an annual plan/focus with priorities and operational direction. Further, that this plan and the subsequent activities, travel reports and results are consistently and transparently shared in a manner that:

- Global Affairs and OGDs in management and working-level are informed and in better position to advocate in their relevant contexts. In particular, Heads of mission are equipped with the knowledge to lead on this issue abroad.

- Domestic stakeholders are equally informed and consulted.

Likeminded countries, current and potential partners can approach Global Affairs to work on synergistic and complementary priorities.

1.0 Introduction

The Evaluation Division (ZIE) is mandated by the Treasury Board Secretariat (TBS), through its Policy on Evaluation (2009), to conduct evaluations of all direct program spending of the Department of Global Affairs Canada (GAC) (formerly Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada (DFATD)), including grants and contributions.

The Evaluation Division tables its reports to the Departmental Evaluation Committee (DEC) which is chaired by three Deputy Ministers of the Department. The formative evaluation of the Office of Religious Freedom (ORF) was conducted as part of the approved regular and systematic cycle of program evaluationsFootnote i. The results meet the requirements of the 2009 TBS Policy on Evaluation and the 2008 TBS Policy on Transfer Payments as well as the related TBS Directive on Transfer Payments that addresses funds to foreign recipients which is relevant to the RFF.Footnote ii Funding for the ORF, including the RFF, sunset at the end of Fiscal Year (FY) 2015-2016.

1.1 Background and Context

The Government of Canada (GoC) believed Canada was uniquely positioned to protect and promote religious freedom worldwide as it is a pluralistic country with a diversity of cultures and religions.

In June 2011, the GoC made a commitment in the Speech From The Throne to create an Office of Religious Freedom (ORF) to help protect religious minorities and to promote pluralism. ORF was housed within GAC and came into operation in February 2013. The Office was unique in its role with an appointed Ambassador to focus on the theme of freedom of religion or belief. It had a four-year mandate from 2012-2013 to 2015-2016. Based on foundation documents, ORF’s mandate on freedom of religion or belief supported GAC’s Strategic Outcomes to Influence and Shape the International Agenda to Canada’s Advantage in accordance with Canadian interests and values.Footnote iii Under the responsibility of ORF, the Religious Freedom Fund (RFF) was a grant and contributions program of $4.25M each year that financed projects outside of Canada to assist religious communities facing intolerance or persecution in a particular country or region of the world.

This evaluation’s 28 month reference period was from June 2012 to the end of October 2014. The reference period captured the approval of ORF’s governing documents and included the 21 month period that ORF had been in full operation (February 2013 to the end of reference period of October 31st, 2014). Within the reference period, the evaluation also considered the time lag of 8 months from when the ORF’s governing documents were approved to when an Ambassador was named to the Office on February 19, 2013.

The purpose of the evaluation was to assess the relevance and performance of ORF, as well as the effectiveness of its governance structure and main activities. Since the ORF was not in full operation long enough for a summative evaluation, this formative evaluation considered whether the activities were producing the outputs and immediate outcomes and if these outcomes were on track to generate the intermediate and ultimate outcomes. This evaluation was conducted between October 2014 and April 2015.

1.2 Program Objectives

ORF built on Canada’s past and current diplomatic efforts to promote and protect human rights around the world, including defending freedom of religion. Specifically, the Office focused on advocacy, analysis, policy development and programming related to protecting and advocating on behalf of religious communities under threat. ORF opposed religious hatred and intolerance and promoted the value of pluralism and inclusive democratic development abroad. Activities were centred on countries or situations where there was evidence of violations of the right to freedom of religion or belief, which may have included violence, hatred, and systemic discrimination.

ORF had the following three-pronged mandateFootnote iv:

- Defending religious minorities; monitoring religious freedom; and, calling attention to the religiously persecuted and condemning their persecutors.

- Promoting religious freedom as a key objective of Canadian foreign policy and encouraging greater attention to freedom of religion along the rights enunciated in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights as well as other human rights instruments.

- Advancing policies and programs that support the right to freedom of religion and promoting the pluralism that is essential to the development of free and democratic societies.

Flowing from the mandate, the program objectives were:

- To compel action internationally against violations to religious freedom by contributing to greater awareness of threats to religious freedom and by promoting pluralism.

- To strengthen GoC response to specific violations of religious freedom.

The five main activities of ORF were:

- advocacy on behalf of religious freedom,

- analysis and reporting,

- training of Canadian diplomats,

- consultations with Stakeholders; and,

- programming that will entail the management of grants and contributions (RFF).

The Office was mandated to undertake outreach and speak publically both domestically and abroad. Activities in advocacy and consultations consisted of meetings between the Office and with religious leaders and representatives of likeminded countries. The Office was expected to oversee the enhancement of reporting on freedom of religion or belief in order to improve the information available. Analysis and reporting included the development of country profiles that would assist in the identification of target or critical regions or issues. Working with the Canadian Foreign Service Institute (CFSI), the Office was expected to develop training on religious freedom or belief for Canadian diplomats.

1.2.1 RFF objectives

The RFF was the principle program through which ORF was programming for results that benefit local communities. Specifically, RFF’s overall mandate was:

- To compel action internationally against violations to religious freedom by contributing to greater awareness of threats to religious freedom and by promoting pluralism.

- To strengthen GoC response to specific violations of religious freedom.

- To promote education on issues of tolerance and freedom of religion.

The Fund aimed to support projects that focussed on:

- building tolerance and dialogue among religious groups;

- awareness to integrate issues on tolerance and education on freedom of religion;

- research and the development of tools to support government engagement in religious freedom, tolerance and pluralism; and,

- legal support or specialized services to support freedom of religion and respect for pluralism on behalf of persecuted groups and individuals.

RFF only funded projects that took place outside of Canada and targeted civil society recipients abroad, including:

- Non-governmental organizations, communities, religious organizations, academics/research institutes or not-for profit organisations;

- International, intergovernmental, multilateral and regional organisations; and

- Canadian non-governmental organizations, communities, religious organizations, academic research institutes operating abroad.

The ultimate outcome of RFF was that human rights protection and physical safety of religious communities were addressed and secured.

1.3 Governance

ORF reported to the Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs (USS) through the Security and Political Affairs Assistant Deputy Minister (IFM). Over the course of the evaluation reference period, the ORF’s results shifted from alignment to Strategic Outcome 3: International Development and Humanitarian Assistance to Strategic Outcome 1 on Canada’s International Agenda. ORF supported the Program 1.2 on Diplomacy, Advocacy and International Agreements and aligned to sub-programs 1.2.1 and 1.2.2 on bilateral and multilateral diplomacy and advocacy, respectively.

An Interdepartmental Consultative Committee (ICC) was responsible for coordination of policy, priority-setting, and programming between OGDs. According to the foundational documents, the ICC was expected to include Director General (DG)-level engagement from IRCC and other departments as required. The ICC also included the GAC DG responsible for human rights and a DG with geographic responsibilities to ensure coherence on related programs and geographic operations.

Guided by the foundational documents, ORF was expected to work in close collaboration with missions and geographic divisions to develop strategies on specific countries.

The significant milestones of the Office’s start-up and corporate administration were:

2011 June - Speech From The Throne announced the creation of the ORF

2012 July - Treasury Board approved governing documents

2013 February - The Ambassador was appointed

2013 May - The first ICC was held

2013 July - RFF became operational

2013 November - Following amalgamation, the ORF moved branches under a new ADM (MFM) for Global Issues and Development

2014 January - The RFF became a pilot program for the new Authorized Programming Process (APP)

2014 March - The ORF was moved under a new ADM (IFM) for International Security and Political Affairs

2014 November - The second ICC was held

1.3.1 RFF management

The funds for RFF were guided by the Treasury Board of Canada’s Policy on Transfer Payments and the program’s foundational documents. The following were some of the basic elements which RFF was expected to follow:

- Information about RFF is made available to missions and on corporate websites.

- A standardized template for applicants.

- Use of ICC reviewed criteria to assess the proposed projects.

- Project Selection Committee (PSC) to recommend projects to the Office of the Minister of Foreign Affairs (O/MINA).

- Progress reports and/or performance reports by recipients. Contribution recipients to report against performance indicators and grant recipients to report on outcomes in relation to performance indicators specified in the agreement.

- Active monitoring of projects by the Office in conjunction with missions.

- Reporting of RFF’s spending towards Official Development Assistance.

The Project Selection Committee (PSC) was comprised of the Ambassador for Religious Freedom, the DG with responsibilities for human rights policy, and Directors with the geographic responsibilities for the area where projects were being submitted.

ORF was responsible for assessing applications of RFF, making recommendations and negotiating the agreements. However, the monitoring of the implementation of the projects was shared with missions.

1.4 Program Resources

The foundational documents approved ORF for five Full Time Employees (FTE)s.

- Ambassador (Governor-in-Council appointment ) – EX-2

- Deputy Director – FS-04

- Senior Policy Officer – FS-03

- Senior Programming Officer – EC-06

- Administrative Assistant – AS-02

In addition, the following temporary positions increased the staff complement:

- 2 PM-4 Policy and program officers (Jan/Feb 2014 to current)

- 1 FS-3 Special Advisor (September 2014-June 2015)

- 1 PG-4 to support the programming of the RFF (8 month assignment)

- 1 Senior Communication Advisor from the Media Relations Office assigned to support ORF’s external communication as part of his files.

The two PM staff and the FS special advisor positions were temporary. The planned total cost of the ORF initiative over four years was $21,587,019. Of this, $20,000,000 was sourced from the International Assistance Envelope (IAE) and the remaining $1,587,019 came from existing reference levels. A total of $4,293,787 was charged to Vote 1, (Operating expenditures), $17,000,000 was charged to Vote 10, (Grants and Contributions), and $293,232 was set aside for PWGSC accommodation.

1.4.1 The Religious Freedom Fund

RFF received $4.25M per year over a four year period (2012-13 to 2015-16), of which $2M is devoted to grants and $15M to contributions. The overall amount for the RFF over 4 years is $17M. The maximum allowable grant towards a project is $500,000 and the maximum amount for a single contribution agreement or project is $1.25M.

2.0 Evaluation Scope & Objectives

The goal of this first and formative evaluation was to provide senior managers at the Department with a neutral and evidence-based assessment of the ongoing relevance of ORF, its structure, policies, procedures, and resources. It also assessed whether or not its activities to-date were on track to produce the expected results.

The specific objectives of the evaluation were as follows:

- To examine the relevance of ORF by assessing the extent to which the program was on target to address the needs of Canadians and its clients, as well as its alignment with federal government priorities and GAC strategic outcomes.

- To examine whether ORF activities were on target to progress towards expected outcomes.

- To examine whether ORF activities, processes and programming were demonstrating efficiency and economy.

- To examine the effectiveness of ORF in meeting its mandate, including whether the program was complementary, overlapping or duplicating work in other areas of GAC.

3.0 Operational Considerations/Key Considerations

The process of operationalizing ORF took almost two years starting from the June 2011 Speech From The Throne to the February 2013 appointment of the Ambassador. The delay in establishing the ORF meant that there was also a delay in carrying out its mandated activities. At the time of the evaluation (October 2014), there had been one round of training on freedom of religion or belief diplomacy to roughly 30 participants and 12 approved projects at the end of the evaluation reference period—of which some were at the beginning stages. The Office was still at the front end of longer term advocacy work. A subsequent second round of training occurred in June 2015 after the reference period of this evaluation.

Immediate outcomes were examined as they were timely. It was too early to identify some of the longer term results and outcomes. Whether it was project outcomes or direct diplomacy, the results and substantive change in freedom of religion or belief was viewed as requiring long-term engagement. Thus, the evaluation’s assessment of return on investments was not as fulsome as a summative evaluation.

The evaluation took into consideration the international work and literature in this discipline while balancing this with the capacity and mandate of ORF. This was a relatively new formalized topic on the global diplomacy agenda and, as a result, there was limited measurable benchmarks and baseline data of the Office’s expected activities, achievements in the field, or knowledge in this subject matter—in particular as it related to Canada. ORF was working on the intent that results were to be created abroad where Canada’s results are measured by degree of influence. Assessing diplomatic influence abroad is a common challenge in evaluating the effectiveness of diplomacy.

3.1 Religious Freedom Fund

The evaluation set out to examine the extent to which the current model of obtaining and delivering projects was the most appropriate and efficient. The following detailed background information was required.

The first set of 10 RFF projects were inspired by the Stabilization and Reconstruction Task Force (START) project funding mechanism—the Global Peace and Security Fund (GPSF)— by adopting their templates and Terms and Conditions. In addition, ORF contacted missions to gather options on possible projects. Project options were refined and narrowed down with consultations of the relevant missions and Geogroups. The PSC reviewed a two-page proposal from the applicant that had been vetted with missions and Geogroups. Once O/MINA had approved, ORF proceeded to request detailed documentation (e.g. budgets, logic framework) from the applicant and these were reviewed before signing a grant or contribution agreement.

In 2014, following amalgamation of the Department, the ORF’s RFF became a pilot for the Authorized Programming Process (APP) as there was direction to consider a single and standardized process to the Department’s management of grants and contributions. In order to manage the transition of the RFF into the APP, RFF program administration took a step-by-step approach into an APP-hybrid model. The APP took effect in January 2013 in GAC’s Development programming and it is the former Agency’s systematic process for complying with the Policy on Transfer Payments. The APP offers five mechanisms for project identification and selection which are: unsolicited proposals; Department-initiated proposals; institutional support; request for proposals; and, call for proposals.

Later RFF projects following the APP-hybrid model were required to develop a lengthier and more robust application process which included provision of a financial report, a performance measurement framework, logic models, a review of project against thematic issues, an assessment of project against selected criteria as well as vetting with missions and Geo divisions in advance of decisions taken at the PSC. The RFF’s Call for Proposals (CFP) which followed the APP-hybrid model was initiated in 2014 with a deadline for submission of August 4, 2014. Thus, the following RFF activities falls under the evaluation reference period and will be reflected in the findings:

- 10 projects under the START/GPSF-inspired model

- 2 projects under the Department-Initiated APP-hybrid

- 1 Call For Proposals under the APP-hybrid

Across the above mechanisms and processes, the evaluation also considered potential synergies of the RFF alongside existing GAC programming.

4.0 Evaluation Complexity and Strategic Linkages

The responsibilities of ORF included not only a new fund but also a mix of training, policy development, and advocacy. Thus, data gathering and analysis reflected all of these areas of activities. ORF was expected to lead and support GAC’s knowledge and fund programming in an unfamiliar and specialized policy priority.

While ORF was expected to plan and program to operationalize its mandate, ORF also responded to unexpected demands of crises or hot spots. These requests may have placed pressures on a small and new Office to balance reactive versus planned work in both its policy and programming activities.

The majority of knowledge required on freedom of religion or belief is nuanced to specific regions, governments, and civil society. This included the relevance of freedom of religion or belief to a broad range of themes from education and rule of law to trade. Often these connections and opportunities materialized at a mission. It was also difficult to demonstrate the value of building relationships on freedom of religion or belief for ORF and the GoC until they were needed—potentially in a crisis. Further complexities included the differing levels of interest and effort among Canadian diaspora to the issues of freedom of religion or belief in their home countries.

While the evaluation was focussed on addressing the evidence to support the core issues, the ORF started with a multitude of perceptions. The announcement of the Office created broad expectations as well as skepticism concerning its role. It automatically placed the work and communications of the Office closer to media and public scrutiny. There was also anticipation and interest about the Office, including the role and function of the Ambassador, both inside the Department and amongst relevant stakeholders. When pertinent, the evaluation questions and findings reflect some of this context.

5.0 Evaluation Approach & MEthodology

The formative evaluation followed the 2009 Treasury Board Policy on Evaluation and the related Directive and Standard. The reference period for the evaluation was from June 2012 to the end of October 2014. The evaluation questions assessed the relevance and performance of the program using the five core evaluation issues. They were aligned to data sources and analytical approaches that are defined in the Evaluation Matrix.

5.1 Evaluation Design

The evaluation was conducted in-house by ZIE evaluators. Given the absence of empirical data in this policy domain, a mixed method approach was employed using a variety of techniques to collect both qualitative and quantitative data.

In-person and telephone interviews were conducted with stakeholders that included GAC staff (at HQ, and missions as well as with heads of mission), other government departments, domestic religious stakeholders, key stakeholders of likeminded countries and organisations, partners of the RFF, and academics. One field visit to Washington, DC was conducted to assess both relevance and performance. The field visit supported observational data, including best practices and lessons learned of governments working to promote freedom of religion or belief. Document analysis was used to demonstrate evidence of activities, planning and reporting, governance oversights and outputs. The information collected was triangulated to delineate a performance story, identify possible trends, similarities, and points of divergence.

A decision to cancel the survey directed at participants of the ORF 2014 training was taken for the following reasons. From the 2014 CFSI training course on religious freedom, the evaluation team had received comprehensive details of each participant’s course evaluations, making some of the lines of inquiry redundant. Secondly, the participants of the course were not all staff going on post, a significant number were HQ-based as well as employees from several OGDs, thus it would have been difficult to tailor common questions suitable for such a diverse group and there would have been a risk of a low response rate. To mitigate this methodology change, training and knowledge questions on freedom of religion were raised as part of introductory questioning where possible, especially within GAC. Comparative analysis of the US and the UK Ministries of Foreign Affairs training on freedom of religion or belief also complemented this line of inquiry.

Other aspects of comparison included GAC funding programs, likeminded countries’ approaches to funding on religious freedom, as well as relevant organisation’s raison d’être, and other organizations’ challenges and scope of work in overlapping and similar fields.

5.2 Data Sources

5.2.1 Interviews

In collaboration with ORF, an internal and external contact list was developed for HQ and abroad. A purposeful sampling strategy was used to select interviewees. Criteria included: consultation from ORF; ZIE’s own literature review; and, sampling interviews that reflect the composition of each group. Seventy-five interviews were conducted, 23 were completed by phone. As some of these interviews had multiple interviewees, a total of 88 people were interviewed. This is roughly 25+ more than originally scoped. More interviews supported the cancellation of a survey for the participants of the CFSI course on Freedom of Religion. Additional breakdown is provided below in the following tables:

As the roles and positions of the interviewees vary, stakeholder groups received customized questions from the Master Interview Protocol in order to gain a meaningful understanding of their specific expertise and roles and the specific activities (e.g. Heads of Mission, Geographics, Religious Leaders). In addition, three of the interviewees responded to the interview questions in writing. Two of them were partners in the RFF and were able to provide more fulsome answers in this manner and one expert was traveling too often to find a suitable time to answer the questions by phone. Additionally, 8 interviews provided additional supporting documents or elaborated on the interview questions by email subsequently. Findings from interviews were relevant across all evaluation questions and some of the written information provided afterwards made the interview data collection more robust.

5.2.2 Field visit

On-site interviews provided valuable insight into implementation of religious freedom as a foreign policy objective. Observational data contributed to assessing the similarities and differences in the US Office of International Religious Freedom’s (IRF) mandate, best practices and lessons learned. It also allowed the evaluation team to gather views on Canada and ORF’s leadership from another view point. The State Department is one of the few opportunities to appreciate the scope and reach of this subject area for Canada over a longer time horizon.

In-person interviews took place with:

- WSHDC staff

- United States Office of International Religious Freedom (State Department)

- United States Special Representative for Religion and Global Affairs (State Department)

- Office of Global Programming, Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor (State Department)

- United States Commission on International Religious Freedom

- Academia on Freedom of Religion

- Religious and non-governmental stakeholders of the IRF

5.2.3 Document review

A literature review was conducted to contextualise the ORF within the Canadian and global context. The 250 and more documents included publications from relevant non-governmental stakeholders, research organisations and GAC’s own Religion and Human Rights Initiative found in the GCpedia. External sources included media articles, and academic writings that gaged the issues of religious freedom as well as the reach of the work of the ORF. Pertinent GoC statements were used to gauge direction and coherence of this policy priority.

GAC and ORF documents were reviewed to assess appropriate departmental roles and responsibilities from a policy alignment and coherence perspective. Departmental and branch performance reports and Reports on Plans and Priorities were also reviewed. Documents were provided based on evidence available to answer the evaluation questions. These included foundational documents, committee records, funding decisions, meeting agendas, mission and travel activity reports, contribution agreements, financial and narrative reports,

5.3 Data Analysis

All sources of data were used to address the evaluation questions. Data gathered from interviews and documents met multiple lines of inquiry. Information and findings were triangulated to discriminate trends, similarities and points of divergence or convergence. Comparative analysis was also done to capture the context of ORFs operation, its relevance and how the performance story is being carried out. The evaluation observations and findings were used to answer the evaluation questions delineated in the evaluation matrix. Conclusions and recommendations were based on the evidence and analysis organized in this manner.

Evaluation results including the conclusions and findings were validated during the second Evaluation Advisory Committee (EAC) meeting when the preliminary findings were presented. EAC members provided feedback on the early findings.

6.0 Limitations of the Evaluation

The most significant constraint which placed limitations on the evaluation was the absence of information on performance. This was a factor for several reasons:

- there was minimal information on the performance of programming in religious freedom globally;

- there were gaps of performance indicators and monitoring measures in the RFF; and,

- due to the nascent stage of the Office, including the execution of programming funds, coupled with project delays, reporting on project activities and immediate results were limited.

Consequently, this limited performance information was mitigated in the language and approach to the findings and recommendations. For instance, recommendations address shortcomings in activities and inputs (improve communication and coordination, monitoring of projects) rather than adjusting programming approach to address intermediate and ultimate outcomes that had logically not yet been realised.

Interviews did not cover a census of key stakeholders. Of the six OGD members of the ICC that were approached for interviews, only Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) and Public Safety (PS) representatives expressed an interest. The evaluation team conducted several interviews in each of these departments in order to engage with the relevant sections of IRCC and PS to obtain full coverage of the evaluation issues. ORF was peripheral or complementary to IRCC’s work. PS expressed a strong interest in ORF. However, the interest in PS was forward-looking and not closely involved over the reference period. Further, a representative of the IRCC was a member of the evaluation’s EAC.

Mission interviews focussed on those that were actively engaged in programming and policy. Interviews did not cover all the missions that were contributing reports and activities on freedom of religion or belief for the department. The ORF Ambassador’s relevant contact list was extensive. The evaluation team was not able to interview all likeminded countries in the contact group or all of the domestic and international stakeholders of ORF. Using purposeful sampling and interview questions, interviews continued until there was confidence that observation of interviewees had reached a level of saturation.

7.0 Management of the Evaluation

The Evaluation conducted two in-house EAC meetings. The EAC was comprised of representatives from GAC’s START/GPSF programming, human rights, relevant Geographic Directorates and a IRCC representative.

The EAC, chaired by the Director of Evaluation, met to approve the Evaluation Work Plan and to discuss the preliminary findings. The draft final evaluation report was sent to all EAC members for feedback which was integrated into the final version. The Office of Primary Interest (OPI) was required to provide an official Management Response and Action Plan (MRAP) in response to the recommendations laid out in the Final Evaluation report and to present the MRAP at the DEC following the presentation of the Evaluation Recommendations by ZIE. Once the final report has obtained final approval by the DEC, it will be translated and posted, along with the MRAP, on the Department’s external website.

8.0 Evaluation Findings

8.1 Relevance Issue 1: Continued Need for the Program

Finding 1: ORF worked in countries that demonstrate some of the highest levels of restrictions on freedom of religion or belief and at the same time engaged on issues of freedom of religion or belief where it was thematically relevant. ORF’s mandate selectively covered specific Geographics and missions.

Overall, restrictions on freedom of religion exist in a large number of countries (39 percent) with 5.5 billion people or 77 percent of the world’s population living in countries with a high or very high overall level of restrictions on religion.Footnote v The highest overall levels of restrictions were found in Burma (Myanmar), Egypt, Indonesia, Pakistan and China which were all ORF countries of focus.

ORF was able to enrich the GoC approach to human rights as one of ORF’s key public messages was to highlight the promotion of freedom of religion or belief vis-à-vis other human rights. Some of the factors considered included the ability of ORF to engage diplomatically in a country and the capacity of RFF programming to produce results. Interviews at GAC noted that ORF occupied a presence that would have otherwise been between the Geographics and the human rights division. Having a clear position and policy priority in freedom of religion or belief allowed Canada to focus its efforts in the human rights umbrella of issues. This was noted in existing UN fora as well as with specific Geographics.

Some missions and geographic areas noted that ORF strengthened the work of the mission, and subsequently, Canada’s ability to position itself in the country on issues related to freedom of religion or belief and human rights. At the same time, there were also gaps in the development of policy and statements specific to religious restrictions, such as Sharia law in a given country. Most missions where freedom of religion or belief was a priority would have liked to see even more engagement with ORF.

The evaluation found that the RFF scope allowed for meaningful GoC engagement and programming of freedom of religion or belief in selected missions that it was actively engaged. RFF funded interreligious dialogue and mediation, education and monitoring of information on religious minorities, built capacity of civil society and law-makers on religious tolerance and documented religious persecution of religious minorities.

While ORF operated in some countries and missions, it did not have sufficient capacity to work with all countries in which restrictions on freedom of religion were high. Canadian domestic stakeholders and GAC officers recognized that ORF took decisions on where to prioritize engagement. However some of them expressed a lack of clarity of ORF’s rationale to engage in a particular country or area of work.

There is documented evidence that ORF developed and consulted on some of its countries of engagement and activities, including two ICC meetings and selected GAC geographic operations. However, there was a lack of consistency on how missions and the rest of the Department were consulted or informed on the priorities of ORF. In addition, some interviewees noted a need for regional analysis and further efforts with missions that were not actively engaged with ORF. Understandably ORF’s global coverage would also have needed to be flexible to address crises related to freedom of religion or belief as they arose.

Finding 2: ORF’s advocacy activities were generally viewed as a positive contribution to Canada’s foreign policy among key Canadian stakeholders, but gaps remained in understanding ORF’s function.

The evaluation was not positioned to collect data on whether the right for freedom of religion or belief was relevant to the broader Canadian public.

ORF had extensive outreach efforts to domestic religious and non-religious stakeholders. The diversity of contacts was consistent with Canadian pluralism. Topics addressed with religious leaders included: issues of religious persecution in their homelands, relevance of their organization to ORF, and what the substantial contribution or connection of ORF could be. While the spectrum of interest was wide and the creation of ORF was generally agreed upon as an important decision, the perceptions of ORF were mixed and marked by diverging opinions, observations and lingering misconceptions.

For instance, some organizations with established working relationships with GoC viewed ORF as strengthening their presence and as another avenue to raise the issue of religious persecution. It was also suggested amongst several respondents that ORF should have had a domestic component to its mandate to enhance its credibility and legitimacy so Canada could have led by example. Conversely, one religious organization with an established working relationship within GoC viewed the ORF advocacy and mandate as redundant. The interviewee expressed the view that there was already significant existing leadership to reach out beyond its own religion, including on matters of foreign affairs within the Department.

There was also confusion regarding the mandate and activities of ORF. Despite a dedicated website that laid out the ORF mandate and a social media presence, some organizations were not clear on the ORF’s mandate nor were they aware of the RFF. Some interviewees expressed a concern over the proportion of negative statements by ORF which denounced others publically. Others noted that there was little effort observed to ensure gender parity in its outreach activities. There was also confusion of whether ORF had a consular role or if ORF was placing particular emphasis on particular religions or regions.

Perceptions of ORF were important. For example, Christians are one of the most persecuted minorities in the world, thus ORF’s efforts to support this persecuted minority seemed rational. However if this information is not communicated consistently and accurately in the politically sensitive arena, ORF may be viewed as favoring Christians over all other religious groups. Hence, some stakeholders may interpret actions of ORF as politically motivated. Not surprisingly, the misperception that ORF was a political office was one of the challenges that the Office continued to face.

While the one-on-one meetings with key Canadian religious leaders were a valued approach to initiate dialogue and relationships with Canadian religious leaders, a subsequent lack of a consistent and transparent approach resulted in the mix of opinions expressed above. Religious leaders were not clear on the Office’s priorities or its impartiality when one religious event was chosen over another. Domestic religious leaders and key stakeholders who wanted to further their relationship with ORF and GAC expressed a lack of knowledge of what the next concrete steps in this process would be or how to build a genuinely useful connection. Domestic stakeholders were looking for transparency, including more information about what ORF was doing, what it had achieved, and where it was actively engaged and why. They also sought guidance on how to be a substantive contributor to the achievement of the ORF mandate and wanted to know if they all had equal access to the Office. Both stakeholders and ORF had efficiencies to gain when both parties knew when to include each other, suggest an invitation or work towards dialogue on a specific issue at times when it was most appropriate to do so.

The option of forming an External Advisory Committee to advise ORF on the exercise of its mandate was included in ORF foundational documents. This Committee was expected to take place at the end of June 2015. ORF’s External Advisory Committee could have been a forum for more transparent exchange of information amongst multiple domestic religion organizations.

Finding 3: RFF projects addressed a demand for programming on freedom of religion or belief.

Several lines of departmental evidence as well as input from external organizations demonstrated that there was a demand for funding on freedom of religion.

ORF initiated a Call for Proposals (CFP) over a two-month period in 2014 to disburse $2M. The CFP received more than 200 applications for a very small fund of which RFF projects averaged just above $500,000. Two other GAC funds distributed at mission-level helped demonstrate the relevance of this priority by funding projects under the thematic area of freedom of religion or belief. Since 2011-2012, the Post Initiative Fund (PIF) funded 89 projects in the thematic area of freedom of religion or belief, with projects averaging $2,998. Between 2012 and 2014, the Canada Fund for Local Initiatives (CFLI) funded 15 projects in the thematic area of freedom of religion or belief, with an average project size of $40,256. The latter fund was only open to countries that qualify for Official Development Assistance (ODA).

While RFF does not replace bilateral development funding, GAC interviewees appreciated the availability of the RFF for countries where they would like to continue to engage with relevant civil society once bilateral development funding was no longer available from Canada or for countries that were not traditional aid recipients. Missions and ORF staff appreciated potential partners who had successfully engaged via PIF or CFLI—demonstrating its project capabilities. A few domestic stakeholders familiar with RFF saw some opportunities to connect with their charitable arm or with needs of their communities in their homeland.

There were mixed views within GAC on whether RFF was able to address specific priorities. Some projects under RFF reflected critical priorities and decisions to address them. Others viewed RFF as potential seed funding to develop policy linkages to activities that support freedom of religion. However officers at some Canadian missions lacked adequate knowledge and direction on how to best respond to interest in the RFF. Consequently, RFF may have addressed a portion of the demand to program on freedom of religion or belief.

There were other concerns that RFF (valued at $17M over 4 years) was not enough to significantly influence the mandate, nor were the resources or staffing sufficient to reflect the issue as a Canadian priority. As well, there were concerns expressed that the scope of RFF was too narrow, and the name of the Fund, “Religious Freedom,” was too sensitive or too risky politically for some relevant potential partners to apply. An international human rights organization viewed RFF as very relevant for emerging religious issues in Africa. A number of stakeholders viewed the RFF component at ORF as an essential tool: there were enough western leaders condemning actions of other countries, but there was a lack of “carrots” required to support advocacy and policy work on freedom of religion or belief to produce positive results – something RFF was positioned to do.

8.2 Relevance Issue 2: Alignment with Government Priorities

Finding 4: ORF and RFF were aligned to produce results defined in the Strategic Outcomes of the Department to meet Government of Canada priorities.

Over the course of the amalgamation of former Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) and former Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade (DFAIT), ORF also transitioned between three branches of the Department, presenting its own unique challenges to the management of ORF. The Office mandate over this period of change was consistent and continued to align to GAC’s first Strategic Outcome on Canada’s International Agenda which was defined as “The international agenda is shaped to Canada’s benefit and advantage in accordance with Canadian interests and values” in the GAC – Transitional Program Alignment Architecture (PAA) for 2013-2014 and 2014-2015. This Outcome was redefined as “The International Agenda is shaped to advance Canadian security, prosperity, interests and values” in the 2015-16 PAA.

During the evaluation reference period, working documents demonstrated that ORF contributed to commitments of the International Security and Political Affairs Branch. ORF’s work aligned to “The fundamental right of freedom of religion internationally is advanced by the Office of Religious Freedom through pragmatic and effective programming and outreach in countries and regions where freedom of religion or belief is under threat, as well as through evidence-based strategic policy development.”Footnote vi

Overall, there appeared to be strong alignment of ORF with the relevant sections of the Integrated Corporate Business Plan (ICBP). ORF fully or partially met all of the performance indicators under the ICBP 2013-2014 and 2014-2015.

ORF, through its ability to reach a wide variety of stakeholders to discuss issues on freedom of religion or belief, supported advancement of IFDFootnote vii 1 “Canada’s leadership in advancing the fundamental right of freedom of religion is supported by evidence-based strategic policy and effective programming and outreach in countries and regions where freedom of religion or belief is under threat.”

The evaluation was able to capture specific information that aligned to the Department’s Strategic Outcomes. To support the Branch commitment that “The fundamental right of freedom of religion is advanced by the Office of Religious Freedom through pragmatic, effective programming and outreach in countries and regions where freedom of religion or belief is under threat”Footnote viii

- Performance Indicator: Foreign representatives, religious communities and decision makers were reached through consultations, events and visits.

ORF contributed to the above indicator as it reached out to a wide variety of stakeholders to discuss issues around freedom of religion and belief.

- Performance Indicator: ORF’s information and analysis products on religious freedom met the Government of Canada decision-makers' expectations for content and relevance to Canada's international interests and values.

There was some evidence to suggest that some stakeholders within the GoC received and used work produced by ORF. However, it is noted in subsequent findings that ORF’s reach was not comprehensive and there were a variety of stakeholders that needed to be better informed.

- Performance Indicator: Number of activities (statements, tweets, demarches, speeches, publications, etc.) carried out by the Ambassador to advocate on behalf of persecuted religious communities or individuals persecuted on the basis of the religion or belief.

The Office was very active on social media, there were a high number of activities (e.g. statements, tweets, demarches and speeches) carried out. ORF (including RFF) statements and announcements were also published on the ORF website.

While ORF did not have a domestic mandate, it is worth noting that the GoC’s policy on multiculturalism shifted from ethnic diversity towards greater interfaith dialogue during the evaluation period. This occurred in a context of growing religious diversity. Under IRCC’s multiculturalism policy and programs, IRCC supported interfaith programming in Canada.

Where ORF had direct interaction on freedom of religion or belief, it enriched the GoC’s human rights agenda by providing clearer direction to raising awareness on the protection of ethnic and religious minorities. However, it was noted that the level of information sharing and leadership was uneven between relevant missions that were involved in advancing Canada’s international human rights agenda.

Finding 5: ORF took action so that Canada influenced and led on freedom of religion or belief with likeminded countries’ Ministries of Foreign Affairs and with leaders and HOMs in countries of active engagement.

The creation of the Office allowed for advocacy to be approached through multiple avenues, included but not limited to a positive impact on several specific cases of religious persecution. Canada was able to pursue opportunities to work with some organizations in common positions including specific aspects of the UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Religion or Belief.

Amongst likeminded countries and relevant international organizations, Canada was relevant not only as part of a group of likeminded countries, but also as a global leader addressing a gap. The absence of a US Ambassador for their Office of International Religious Freedom for a period of one year left a void in the international arena. Furthermore, interviewees in the US expressed openness to having another country take leadership on the right for freedom of religion or belief. The US did not see itself as needing to lead all initiatives on religious freedom. Rather the possibility of playing a supportive role at times was viewed as a positive change that increased their diplomacy options on the same thematic issue. Other likeminded countries received some positive benefits from working with Canada’s leadership on freedom of religion or belief. Specific examples included the coordination of a contact group and a specific advocacy project to jointly démarche a country with high-levels of religious persecution. While leadership of ORF allowed for such advocacy to be pursued, likeminded countries also appreciated a common message penned by ORF that was able to be adjusted to suit the diplomatic specificities of each country’s interest.

As one head of mission noted, the topic of freedom of religion or belief was relevant, including, for example, to the countries of the Commonwealth. Canada is a small country but an important player, so having ORF and the clear Canadian policy priority allowed for Canada to stay engaged and maintain a strong, international voice. Overall, international interviewees noted that as there were only a limited number of actors and leaders on freedom of religion or belief, Canada‘s work in this area was appreciated since it addressed a gap.

8.3 Relevance Issue 3: Consistency with Federal Roles & Responsibilities

Finding 6: Location of ORF under the security umbrella was logical as it was near human rights work, but not directly under it.

Overall, there was no strong objection or consistent view that the location of ORF needed to be elsewhere.

In regards to location of ORF within GAC structure, most interviewees with relevant knowledge of the department appreciated that as a policy priority, freedom of religion or belief was relevant beyond human rights. Some saw mainstreaming of freedom of religion or belief into the work of GAC as a later logical step. The location of ORF under the umbrella of International Security and Political Affairs Branch (IFM) was viewed as having the potential to reach out more broadly to the relevant areas of GAC policy and programming. ORF was co-located with the human rights bureau in the “I” Branch so that they could work closely on relevant files while maintaining distinct activities and leadership.

In terms of delivering on grants and contributions, CFLI and GPSF were two programs that at times delivered grants and contributions related to freedom of religion or belief. There was some discussion at the outset of placing RFF under GPSF or CFLI. Interviewees at mission and at HQ expressed an interest in the CFLI and other smaller and decentralized models that were better able to align the RFF projects with local country needs and approach relevant civil society in the most diplomatic and sensitive manner. ORF did have some limited exploration with GPSF, however their Terms and Conditions and accountabilities were different, limiting the capacity to proceed with a transfer to GPSF.

Within GAC, some geographic desks were able to strengthen their approach on the protection of religious minorities following the emergence of religious persecution. There was significant interest in potential synergies of freedom of religion or belief to other policy and programming areas.

Among OGDs, there was a generally neutral response to role and location of ORF as it did not significantly affect their work. As the mandate of ORF was to work abroad, there were only a few comments that it was logically placed in GAC.

Externally, among relevant stakeholders that were familiar with the organization of the GoC, such as religious leaders and non-governmental organizations, their perceptions were more disconnected, but included mixed views on the objectivity of the Office, resources necessary for the Office and level of engagement with domestic leaders. Factors that may have contributed to these inconsistent views included the lack of information-sharing by ORF or a lack of understanding of the detailed structure of GAC.

Finding 7: ORF’s mandate was clear for GAC officers who were directly involved, but there was room to clarify and increase communication on the ORF’s mandate and operations to the rest of the Department.

ORF’s roles and operationalization of its mandate were clear to key sections and key contacts that worked closely with ORF. They found the collaboration and ability of ORF to nuance its mandate into specific regional and local issues invaluable, including but not limited to regions such as Ukraine and the Middle East. It was clear that, for those sections, ORF brought a wealth of knowledge and expertise, and the roles and approaches to collaborate were streamlined and well-identified. GAC sections that were closely engaged with ORF would have liked the Office to be more involved in a longer term approach of strategic planning and including potential projects.

Where pertinent sections of GAC and OGDs did not understand how ORF’s mandate was actioned, the negative impacts of this included raised expectations regarding ORF, excessive number of queries, and irrelevant requests for ORF staff to field. A common theme that was echoed among stakeholders both inside and outside GAC was that ORF’s mandate was clear. However, beyond those that are working closely with ORF, it was not clear how ORF was operationalizing this mandate. From GAC interviewees, the disconnect seemed most apparent at the working-level in identifying practicalities. What was ORF doing? Who was leading which aspect of the main activities? Who was the best person to contact and engage? What parts of the mandate were active and how were they reaching out on this? In several specific cases, a request for ORF’s input was last minute—as an afterthought. This placed extra pressure on ORF’s small staff to catch up within the GAC internal processes. ORF staff were not able to plan or streamline their work as they were copied on every visit of a religious leader when it was not relevant to the Office’s operation or mandate. ORF staff often had to field any requests containing the word “religion” as others in the Department lacked an appreciation of the work that ORF undertook. Without a further appreciation of the details of the work of the Office, a limited number of interviewees internally and externally expressed a concern that the ORF mandate was limited to focusing on only one issue of human rights.

Within Canada, other government departments saw the leadership of ORF as timely, including creating possible connections between diasporas and communities in their homeland, and possible links to other relevant issues, such as countering violent extremism. OGDs viewed ORF as adding credibility to this foreign policy priority. They noted that the ICC met once a year, as per its mandate in the ORF’s foundational documents, and that the information was high-level. Missions where ORF had visited saw its presence as relevant to expand the mission’s network of civil society and stakeholders. ORF led round tables with civil society, religious leaders and other heads of mission and created networks that were appreciated by the head of mission and for the political section.

While ORF could not address the entirety of its mandate at once, more information on ORF’s approach may have provided clarity to the above considerations. ORF’s ability to enrich the work of one human right was partially due to the well-coordinated approach of the human rights bureau. OGDs interviews at the working-level and management would have liked to have gained a better understanding of the operationalization of the mandate in order to see where there was parallel messaging, policy alignment and potential synergies and lessons learned. Thereafter, ORF staff would have been better able to focus on addressing the misaligned perceptions from some stakeholders including the examples identified above.

To ensure that it was a meaningful exercise, external and internal stakeholders required different information. There was still room for ORF to remain flexible to respond to the unexpected demands. A number of interviewees expressed an interest to better understand the timeframes of how ORF was operationalizing its mandate.

8.4 Performance Issue 4: Achievement of Expected Outcomes

Finding 8: The evaluation found evidence of increased awareness of freedom of religion or belief with some stakeholders, but not all relevant actors.

Overall, ORF made Canada credible in leading on the issue of freedom of religion. Internally and externally, there was an appetite for more knowledge, including on ORF’s positive results. However, Canada’s ability to sustain a convincing line of communication with different stakeholders was mixed. The discussion below breaks down the finding among different stakeholder groups.

Among targeted missions and Geographics, there was clear knowledge about Canada’s leadership and the thematic of freedom of religion with relevant GAC officers. Some religious leaders and likeminded missions of foreign countries were also becoming more aware of Canada’s interest and leadership on freedom of religion or belief. It was yet to be seen the extent a mission’s other areas of programming (e.g. security, development) were able to support Canada’s leadership on this theme. In several missions, it was clear there was a learning curve in regards to ORF’s approach to the mission and the Geographics. ORF reached out to HOMs on several occasions regarding ORF’s mandate and the purpose of the RFF. Missions and Geographics identified areas of weakness, often at the working-level, on mission-specific policy information or knowledge of the RFF. Given that ORF was in operation for just over two years, the initial results were expected. A longer term review would expect to see Canada’s relevance on this issue reach beyond the mission and the diplomatic community.

Canada was viewed as a leader in the diplomatic community and thus was most successful in raising freedom of religion or belief as an issue among this broad group of likeminded stakeholders. This group included heads of missions, ministries of foreign affairs of likeminded countries, international stakeholders and non-profit organizations. Some of ORF’s international stakeholders would have liked to see an improved coordination among the Parliamentarian groups on religious freedom and the diplomatic community. Canada and ORF was recognized as supporting and bridging both these areas of activity. A few stakeholders were even aware of the structure of ORF (relative to the legislatively established US counterpart) and considered it an option for its own ministries.

Among domestic stakeholders, ORF was not significant to all the relevant actors. The observations of the evaluation are mixed. While some domestic religious organizations were satisfied with their relationship with ORF, GAC and GoC at large, other organizations found that there was little information aside from the initial meetings, news releases and social media announcements. They essentially would have liked to have taken stock of what the ORF worked on, and where there were expected results. As previously mentioned, there was a desire for greater information on the work of the Office.

The following were some of the potential areas of ORF activity that stakeholders believed would continue to raise awareness of freedom of religion or belief;, some of the ideas were outside of ORF’s mandate but were included in the list to capture the diversity of views:

- Promoting domestic faith-based stories

- Bringing members of parliament and diplomatic community together

- Creating a cross-country speaking tour

- Communicating positive examples of religious freedom from ORF advocacy and RFF projects

- Documenting a statistical collection of racism and religious discrimination in CanadaFootnote ix

- Having a better understanding of ORF’s approach to policy, projects and priorities.

- Having a better understanding of which organizations ORF is most frequently in collaboration with and why?

- Does ORF response to domestic issues? Does ORF know if Canada is walking the talk?

The list above demonstrated detailed interest in ORF and a request for more equal and accessible information.

Finding 9: Some Foreign Service officers increased their knowledge of freedom of religion or belief as a result of several approaches by ORF to train and inform.

ORF delivered a one-day training in 2014 that demonstrated significant interest by a full class of 30 participants. The feedback was mixed, but consistent with a first-time offering of a course. The majority of criticisms included a lack of Canadian-based knowledge; a narrow focus on sentiment versus policy and academic rationale; a narrow focus on one region; a lack of broader issue contexts such as poverty and conflicts; and, a panel that lacked coherence among the ideas expressed. Also, participants wanted to hear more from the Office. Based on participant feedback, changes in June 2015 included a more situational and Canadian lenses in an expanded two-day course.

In 2015, the Office also presented the foreign policy priority and ORF in the Advanced Human Rights course. CFSI posted a webpage in wiki@international for officers after the course, with relevant position papers, case studies, and broader thematic intersects of specific issues addressed in the course. There were sections for LGBT persons, Child, Early and Forced Marriage and Business and Human rights, but information on freedom of religion or belief, or ORF was absent.

In addition to the course, ORF initiated four Religious Freedom Forums and several brown bag lunches as an effective way of informing on freedom of religion. These included:

- Rising Restrictions on Freedom of Religion and Foreign Policy Responses

- Christians in the Middle-East

- Religion in China Today

- Islam and Religious Freedom

ORF also presented at the out-going head of mission training sessions organized by CFSI. At least one head of mission would have liked to have regular interaction (monthly calls) on matters of freedom of religion or belief.

Among those that were interviewed in headquarters and at mission in the relevant positions, only one person had taken the CFSI course, while a number of people attended either the brownbag lunch or the Religious Freedom Forums. A number of GAC officers viewed the Religious Freedom Forums as a successful method of bringing religious leaders together to learn about specific religions and issues. The brown bag lunches and the quarterly forums reached out to 50 plus officers and external contacts a few times each year.

While the work of training foreign service officers was underway, and the CFSI course addressed a specific activity as outlined in the foundational documents, it was clear that ORF could not rely on the course as the only method of increasing Departmental and foreign service officer knowledge of freedom of religion or belief. The course required a 1-2 day commitment. It was limited to 30 officers and was only available once a year. The course required improvement to match the information needs of the diplomatic service. Users of ORF’s information went beyond foreign service officers and the Forum was a successful complement. While ORF had some success in providing professional development on the subject matter, there were still gaps in knowledge identified across the Department that ORF needed to continually address.

Another source of exposure for foreign service officers on freedom of religion or belief was the drafting of an annual human rights report at missions. Since at least 2012, annual human rights reports required missions to report on freedom of religion or belief as a policy priority, consideration of Canadian intervention and recommendation for future action.

Similar to GAC, both the UK and US Ministries of Foreign Affairs offered a course as well as complementary training activities.

Religious freedom as a foreign policy has been active for over a decade in the United States. The US Department of State operates the Office of International Religious Freedom (IRF) in accordance with their country’s International Religious Freedom Act of 1998 (IFRA). To promote religious freedom and the IRF, the US Foreign Service Institute delivers an optional one-week course on religious freedom with the IRF providing updates.

American diplomats also learn about religious freedom in the field. As part of their IRFA obligations, IRF provides annual reports to Congress on International Religious Freedom which describes the status of religious freedom in every country. The report covers government policies, violating religious belief and practices of groups, religious denominations and individuals, and U.S. policies to promote religious freedom around the world. The report requires junior human rights officers in each post/mission to gather and submit information to this publically available report. Over the course of more than ten years, there is now a solid cohort of diplomats that have knowledge of religious freedom issues in localized foreign settings. Additionally, the IRF provides their mission staff with tasks every year. They recognize that IRF staff who travel to the missions can increase the relevance of an issue as well as energize the human rights officer in the field. All human rights officers going to post routinely meets with IRF before departing. Missions at post reach out to local country religious leaders to gather intelligence. As this work was and continues to be tasked to junior diplomats, their knowledge on issues of religious freedom has now moved up the ranks after 10 years of reporting and intelligence gathering.

Critical of their own approach, key stakeholders in the US mentioned avenues through which the integration of freedom of religion in diplomacy could still be improved. Formal foreign service training in this area could be improved by avoiding a traditional seminar approach and elaborating on areas of relevant study and knowledge for a deputy or chief of mission/section. Training in religious freedom requires very relevant case studies, specific to regional issues, and knowledge of the region (Middle-East and North Africa versus ASEAN or Europe). It is also important to better utilize local people and to include thematic approaches, such as countering terrorism. They also recognize that the annual training course has limits. Currently, there are 20-40 participants each year. If instead the course was offered twice a year, that could increase the potential to 80 people.

The UK recently developed a one-day course on freedom of religion or belief for its diplomats. The training is tied to specific situations, including framing freedom of religion under human rights and security. Their training and information sharing sessions address areas of higher attention such as the Middle-East, as some geographically regions attract and promote greater knowledge on religious freedom overall. Their training course was designed by a team of academics who spent time consulting with diplomats, the latter of whom had been working in relevant regions and issues. They also interviewed officers with experience on a case-by-case basis, including at post, to build the training material.

To conclude the UK training, a panel of relevant ambassadors (including to the Holy See) discuss freedom of religion or belief. Their training, like that of Canada and the US, is not mandatory. They have also brought in relevant journalists (BBC) to share their stories from the field as part of information sessions. UK’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs have noted that their quality and volume of reporting on freedom of religion has improved since the training program was implemented three years ago.

Finding 10: Better information-sharing between the ORF and other areas of the Department was needed to communicate information on the ORF mandate, priorities, activities and results.

ORF had a small staff of 4 plus 2-3 or more on a temporary basis. There was one Ambassador to address freedom of religion or belief to domestic stakeholders, at missions and in international fora. During the evaluation’s 28 month reference period, the Ambassador travelled for 61 days domestically and 86 days internationally. The Ambassador role had to balance outreach with advocacy to include meeting the communication and decision-making requirements at HQ. The Office relied on its direct engagement to achieve success in its activities and results. Consequently, there were some successful engagements with key sections of GAC, but the rest of the Department still lacked clarity.

Examples of gaps in understanding included questions by GAC officers on what was meant by “country of focus/engagement”. While there was evidence that country strategies were developed by ORF in consultation with Geographics and missions, this question remained in the Department. Little information was shared regarding how ORF was working to achieve its mandate vis-à-vis priority setting (activities, countries, thematic) or results achieved.

More specifically, several interviewees noted there was a gap on ORF’s work with GENEV. This mission worked almost entirely on human rights in a multilateral and bilateral context at the working-level and above. Geneva hosts the UN Human Rights Council as well as the UN Special Rapporteur on freedom of religion or belief. GENEV’s network was directly relevant to forging GoC leadership with international institutions, foreign countries, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) that were advocating or programming on areas of freedom of religion or belief.