Synthesis of Evaluations of Grants and Contributions Programming funded by the International Assistance Envelope, 2011-2016

February 2017

Table of Contents

Acknowledgments

The Development Evaluation Division would like to acknowledge the contributions of the many individuals whose knowledge, expertise and efforts were central to completing this review. The Evaluation Division of the Office of the Inspector General jointly undertook this review, and staff from Global Affairs Canada’s Development Policy, Development Research, Program Coherence and Effectiveness provided valuable contributions to the planning and review processes. Specialists in the areas of results-based management, cross-cutting themes and financial resource planning offered technical advice and important contextual information to situate the findings of the synthesis.

A special thank-you is extended to the members of Global Affairs Canada’s Programs Committee and Directors’ General Program Committee for sharing their views on the preliminary findings and identifying opportunities for further analysis.

We would like to acknowledge the work of the team of consultants from Universalia who carried out the assignment: Mariane Arsenault, Anne-Marie Dawson and Katrina Rojas. The project was supervised by Andres Velez-Guerra and managed by Eugenia Didenko who prepared the final report for distribution.

David Heath

Head of Development Evaluation

Acronyms and Abbreviations

- AfDB

- African Development Bank

- APP

- Authorized Programming Process

- CFLI

- Canada Fund for Local Initiative

- CIDA

- Canadian International Development Agency

- COP

- Conference of the Parties

- CSO

- Civil Society Organization

- DAC

- Development Assistance Committee (of OECD)

- DFAIT

- Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade

- DFATD

- Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development

- GAC

- Global Affairs Canada

- Gs&Cs

- Grants and Contributions

- IaDB

- Inter-American Development Bank

- IAE

- International Assistance Envelope

- MDG

- Millennium Development Goals

- NGO

- Non-Governmental Organization

- OECD

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

- PCE

- Development Evaluation Division

- RBM

- Results-Based Management

- UNDP

- United Nations Development Programme

- UNFPA

- United Nations Population Fund

- UNICEF

- United Nations Children’s Fund

- WFP

- World Food Programme

- ZIE

- Office of the Inspector General

Glossary

The following terms are used in this report.

Term | Operational Definition |

|---|---|

Aid Modality | A way of delivering official development assistance, for example through bilateral, multilateral or Canadian partnership channels. |

Civil Society Organization (CSO) | Non-governmental, non-profit and voluntary driven organizations, as well as social movements, through which people organize themselves to pursue shared interests or values in public life. |

Contribution | A conditional transfer payment from the Government of Canada to a recipient in which there are specific terms and conditions that must be met by the recipient. Contributions, unlike grants, are subject to performance conditions that are specified in a contribution agreement. |

Country Program Evaluation | An assessment of the relevance, effectiveness, efficiency, sustainability and cross-cutting themes of development programming in a specific country over a given period. Country program evaluations contain findings, conclusions and formulate recommendations to improve development programming. |

Delivery Mechanism | A contractual arrangement or mechanism used to enter into agreements with entities delivering aid programs. |

Development Effectiveness Review | A review that focuses on assessing the development effectiveness of multilateral organizations using common criteria of relevance, effectiveness, efficiency, sustainability and cross-cutting themes, and draws on evidence provided in evaluation reports from multilateral organizations being assessed. |

Fragile state | A state that faces particularly severe development challenges and is characterized by complex national and regional contexts, weak institutional capacity, poor governance, political instability, ongoing violence or a legacy of past conflict. Programming in fragile states involves humanitarian assistance and emergency services, and seeks to enhance long-term development by improving the effectiveness of public institutions, fostering stability and security, and supporting the delivery of basic services. Fragile states where Canada provided development assistance include Afghanistan, Haiti and South Sudan. |

Good Practice | A successful approach highlighted in evaluation reports that can provide directions to future development policies and programming. |

Grant | An unconditional transfer payment where the eligibility criteria applied before payment assure that the payment objectives will be met. An individual or organization that meets grant eligibility criteria can usually receive the payment without having to meet further conditions. |

Inter-Program Cooperation | Inter-Program cooperation is understood as cooperation between the development, humanitarian aid, trade and diplomacy programs of Global Affairs Canada, between different development programs (e.g., multi-bi; bilateral- partnership) or between different foreign affairs programming areas. |

Lesson Learned | A lesson or good practice from previous programs or projects that could be integrated into future programming. |

Non-Traditional Partner | A partner that differs from the Government of Canada’s traditional partners, such as multilateral institutions, Civil Society Organizations, or private sector as executing agency. |

Programming Mechanism | A mechanism identified by the Authorized Programming Process, which refers to programming types as selection mechanisms. There are two groups of selection mechanisms: open track with request for proposals and call for proposals; and targeted track which includes Department-initiated, unsolicited proposals, and institutional support. |

Synthesis | A review for analyzing and synthesising qualitative information from various sources to address specific research questions. |

Executive Summary

This report presents the results of a structured review of departmental evaluation reports of Grants and Contributions (Gs&Cs) programming funded by the International Assistance Envelope. This was a first exercise undertaken by Global Affairs Canada (GAC) aimed at providing a whole-of-Department perspective on its Gs&Cs programming by including evaluations completed by PCE (Development Evaluation, 29 reports) and ZIE (Office of the Inspector General, 11 evaluation reports).

The objective of the review was to identify lessons and recurring challenges to inform future departmental programming and foster horizontal learning. Findings and conclusions presented in this report need to be situated and interpreted within the review’s historical lens. Most of the Gs&Cs programming examined was implemented prior to amalgamation of the former Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) and Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade (DFAIT). The programming responded to the international priorities of the past rather than present priorities. Also, the review crossed all programming areas funded by the International Assistance Envelope. As a result, nuances specific to each programming area were not captured due to a small number of evaluation reports addressing those.

Conclusions

The review revealed that GAC has generated a strong body of evaluation evidence to conclude on the relevance and effectiveness of Gs&Cs programming. However, the evidence to conclude on the efficiency and sustainability of its programming and the advancement of the cross-cutting themes (gender equality, environmental sustainability and governance) was less robust. The review also identified various factors contributing to, or limiting, the achievement of the desired outcomes of departmental programming.

Canada’s comparative advantage was reported to be strong in the areas of policy dialogue and promotion of gender equality and results-based management. Additional evidence was available to highlight successes in establishing partnership with multiple partners, engaging civil society organizations and applying a mix of programming mechanisms.

Relevance: The review found the Department’s Gs&Cs programming was highly relevant and strongly aligned with Canada’s stated international priorities. The programming largely met the needs of its targeted beneficiaries in developing countries, as well as the needs and priorities of Canadians. The programs evaluated were considered relevant to the Department’s mandate to support poverty reduction efforts, but did not reflect the recent emphasis on the poorest and most vulnerable. The review suggested that the Department did not have a common definition of these target groups and that different programs defined and reached them in different ways. Of note, the degree of relevance was shown to relate to a number of factors, such as conducting appropriate needs assessment, engaging partners, building ownership and leveraging their respective strengths, especially at the design and implementation stages.

Effectiveness: The review concluded that Gs&Cs programming was generally effective, although gaps existed in the Department’s ability to demonstrate the achievement of longer-term outcomes. The body of evidence largely came from assessing program success at the output and immediate outcome levels. Programming effectiveness was supported by utilizing strong development knowledge, expertise and skills within the Department and by partners. GAC’s programming showed strong capacity for establishing partnerships, applying a mix of programming mechanism and aligning programming to the needs of beneficiaries.

While Canada was recognized as a strong advocate for the management and measurement of results, the Department showed weaknesses in applying the results-based management approach to its own programming. Limitations were noted in the Department’s ability to generate and aggregate program and project-level data, to develop quality performance measurement tools (logic models, Performance Measurement Frameworks), and to share its performance measurement expectations with implementing agencies. Difficulties in applying results-based management in development cooperation by donors, particularly aggregating data and attributing results to aid funded programming, have been well documented in the literature.

Efficiency: The review pointed to limited evaluation evidence available to conclude on the efficiency of Gs&Cs programming. Most of the evidence was qualitative in nature and recommendations on ways to improve efficiency were not frequently provided in evaluation reports. In part, this was due to limited data available at the program level, lack of comparable data for comparative purposes and also lack of common tools or guidance available to develop and monitor efficiency indicators at the program and project levels.

Sustainability: The review found mixed results overall. In addition the evaluation reports had notable constraints in their scope, which affected the ability to draw firm conclusions in this area (e.g., the timeframe being reviewed that did not allow for the materialization of longer-term results and longitudinal performance data was limited).

Cross-Cutting Themes: The review determined that GAC’s programming was partially effective in integrating cross-cutting themes. Challenges in advancing these areas included lack of understanding of the Department’s expectations for cross-cutting themes by implementing agencies, difficulties integrating the themes operationally and from the performance measurement perspective (e.g., logic models, appropriate performance indicators) and a diminished focus and resources within the Department. Some evidence suggested that combining mainstreaming with targeted interventions in cross-cutting themes might be more effective. This was notable in the area of governance, with some examples in gender equality.

Considerations for Future Programming

The review identified several opportunities for GAC with the aim to advance its Gs&Cs programming. These considerations included:

- Capitalizing and further expanding Canada’s recognized international strengths in the areas of policy dialogue, the promotion of results-based management and gender equality as well as the use of innovative programming approaches.

- Establishing common definitions of beneficiaries, including the poorest and most vulnerable, and objectives.

- Exploring opportunities to engage new and emerging partners.

- Advancing the application of results-based management and providing guidance on how to measure and improve efficiency and sustainability.

- Developing targeted programming in cross-cutting themes, in addition to mainstreaming.

- Strengthening technical support and providing guidance in implementing and measuring cross-cutting themes.

1. Background

This report presents the results of an analysis of corporate evaluation reports that examined grants and contributions (Gs&Cs) programming funded by Global Affairs Canada (GAC) and its predecessor departments through the International Assistance Envelope (IAE).

The main objectives of this synthesis were to:

- Provide an aggregated evidence base to inform the Government of Canada’s International Assistance Review;

- Identify lessons that can help foster innovation, effectiveness and coherence; and

- Contribute to horizontal learning across the Department.

The report is structured as follows:

- Section 1 presents a brief overview of the methodology for the review.

- Section 2 presents the findings of the review in relation to the five main review criteria: relevance, effectiveness, efficiency, sustainability and cross-cutting themes.

- Section 3 presents the conclusions of the review and implications for future policy work.

- Section 4 provides considerations for GAC’s future programming.

2. Methodology

Forty evaluation reports were considered for this review. Of the 40 evaluation reports, 29 were managed by GAC’s Development Evaluation Division (PCE) and 11 were from the Evaluation Division of the Office of the Inspector General (ZIE).

The evaluations were completed between 2011 and 2016 and covered past programming efforts, including some undertaken as early as 2002. The retrospective nature of the review presents its major limitation. Another limitation was a small number of evaluation reports addressing some areas of the programming continuum funded by the International Assistance Envelope (e.g., development, humanitarian aid, security and stabilization). As a result, specifics of such programming may not have been well captured by the review’s criteria, such as, for example, nuances of assessing sustainability in humanitarian action or integration of cross-cutting themes in security programming.

The evaluations provided coverage at the country, regional and thematic level and also covered the work of multilateral organizations:

- 18 were country program evaluations or evaluations that covered two or more countries (PCE);

- 8 were development effectiveness reviews of multilateral organizations (PCE);

- 14 were thematic evaluations or evaluations that focused on specific areas such as security and stability (PCE and ZIE).

In addition to the evaluation reports, the review team examined relevant documents on the evolution of the Department, lessons learned and previous studies conducted by the Department. The review team also carried out interviews with departmental stakeholders during the planning and data analysis phases.

The methodology was based on a structured review of the findings of evaluation reports. To guide the review, a framework was developed based on: the questions outlined in the Terms of Reference; the OECD-DAC criteria Footnote 1 of relevance, effectiveness, efficiency, sustainability; and questions on GAC’s cross-cutting themes (gender equality, environmental sustainability, governance). The framework was fine-tuned to reflect the perspectives gathered during inception phase interviews. To facilitate the review of evaluation reports and coding of information, the evaluation questions were deconstructed into criteria and sub-criteria and put into a review instrument, completed for each report.

Each review element was assessed under three dimensions:

- Coverage: Was the criterion addressed in the evaluation report? (two-point scale: yes/no)

- Rating: The review team provided a rating of each criterion based on information provided in the original evaluations on how the program performed (three-point scale: weak, acceptable and strong). In some cases, reports “addressed” a criterion but did not provide sufficient evidence to rate that criterion. Footnote 2 If a reviewer did not have sufficient information to make a rating judgement, the “no rating” option was selected.

- Narrative justification: Why was this rating provided and what were the contributing factors (positive and/or negative)?

The review team employed several data analysis methods to inform the findings and conclusions of the review. These included qualitative descriptive analysis, quantitative analysis, comparative analysis, and cluster analysis based on type of evaluation (e.g., country program evaluation, thematic, foreign affairs or development effectiveness review).

3. Findings

3.1 Overview

This section presents the results of the review as they relate to the criteria on relevance, effectiveness, efficiency, sustainability and cross-cutting themes. Each section includes:

- Coverage of Criteria: An analysis of the number of evaluation reports that addressed the criteria and associated sub-criteria of interest.

- Key Findings: The distribution of ratings (ranging from strong to weak) on each criterion and sub-criterion as reported in the evaluations reviewed.

- Contributing and Limiting Factors: A qualitative analysis of factors that affected results achievement and the frequency with which these were reported across evaluation reports. While these present an indication of the relative importance of these factors, they should not be considered an exhaustive list for successful programming.

3.2 Relevance of Gs&Cs Programming

3.2.1 Coverage of Relevance Criteria

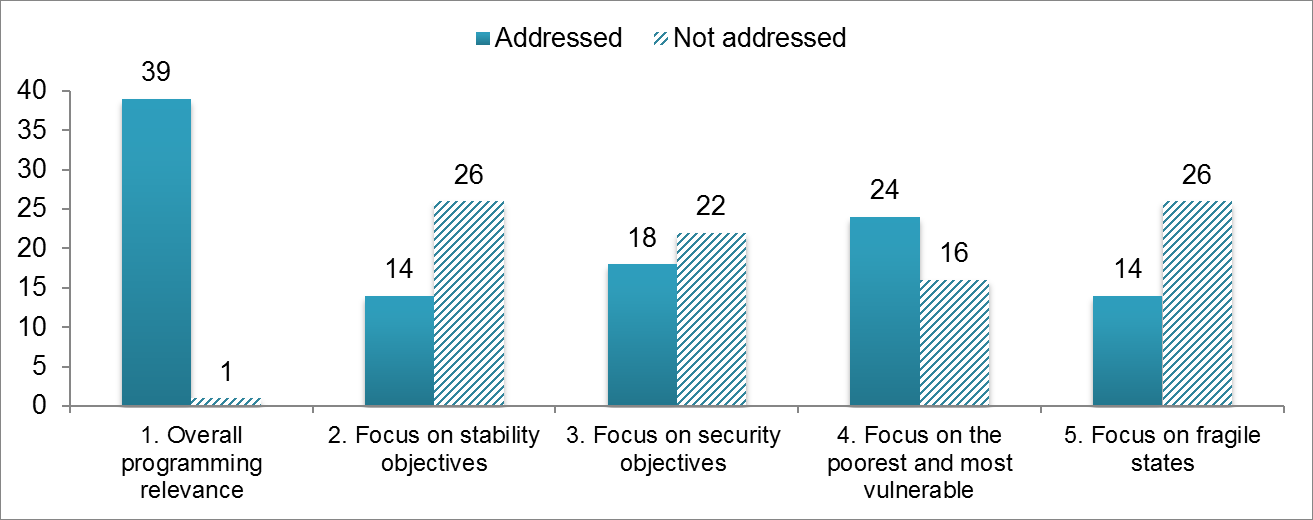

As shown in the chart below, the evaluation reports reviewed consistently addressed relevance Footnote 3 and many of the topics of interest for future programming. Security and stability objectives as well as programming supporting fragile states were covered in less than half of the reports; coverage on these was found mainly in country program evaluations and evaluations from foreign affairs. In addition, while there appeared to be an implicit focus on reaching the poor in many evaluations, the question of whether Gs&Cs programming reached the “poorest and most vulnerable” was not always addressed explicitly in evaluation reports. Most evaluation reports did not discuss whether the programming strategy was appropriate given the country’s development status or income levels, i.e. lower income or middle income country.

Figure 3.1 Number of Evaluations that Addressed Relevance Criteria

Figure 3.1 - Text version

| Rating | 1. Overall programming relevance | 2. Focus on stability objectives | 3. Focus on security objectives | 4. Focus on the poorest and most vulnerable | 5. Focus on fragile states |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Addressed | 39 | 14 | 18 | 24 | 14 |

| Not addressed | 1 | 26 | 22 | 16 | 26 |

3.2.2 Key Findings

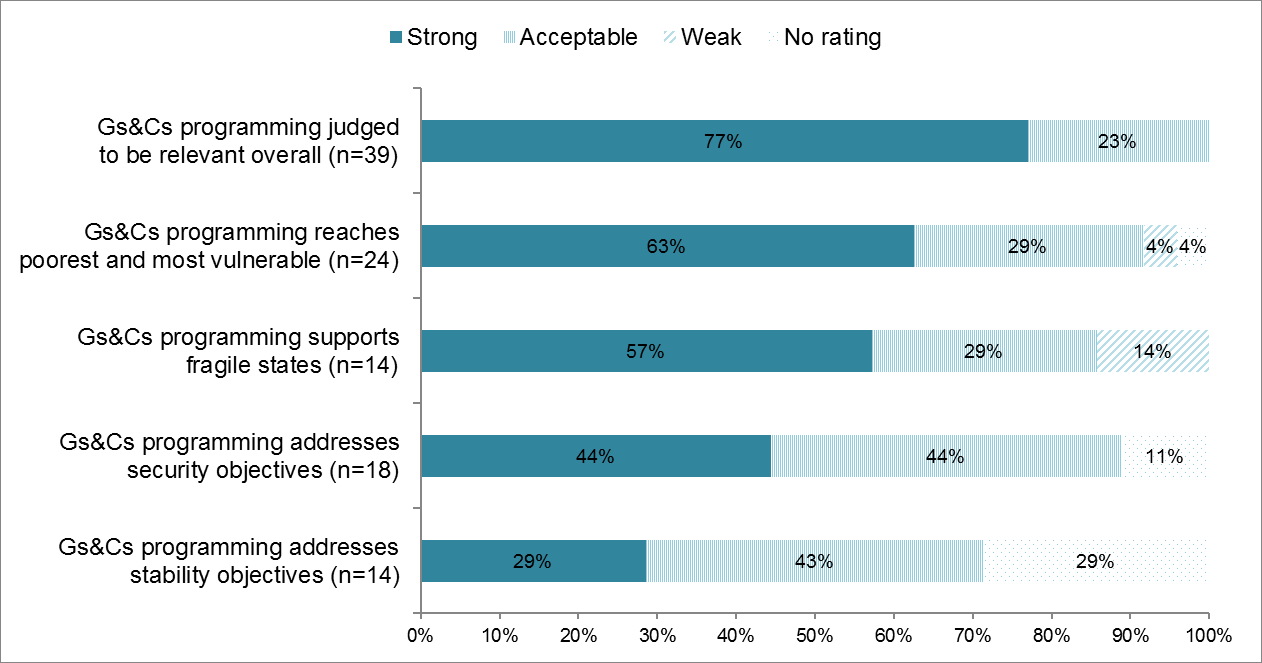

This section presents the assessment of how well Gs&Cs programming performed on relevance criteria and Figure 3.2 on the next page shows the ratings.

Overall Relevance

The overall relevance of Gs&Cs programming was assessed as strong in 77% of evaluation reports, with the rest (23%) reporting acceptable ratings. All reports described a clear rationale for the programming or initiative. Gs&Cs programming was relevant over the period under review, largely due to meeting the needs of beneficiaries and aligning programming to national plans and priorities, including the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). Alignment with Canada’s priorities was also strong. Footnote 4

Figure 3.2 Distribution of Ratings by Relevance Criteria

Figure 3.2 - Text version

| Rating | Gs&Cs programming judged to be relevant overall (n=39) | Gs&Cs programming reaches poorest and most vulnerable (n=24) | Gs&Cs programming supports fragile states (n=14) | Gs&Cs programming addresses security objectives (n=18) | Gs&Cs programming addresses stability objectives (n=14) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strong | 77% | 63% | 57% | 44% | 29% |

| Acceptable | 23% | 29% | 29% | 44% | 43% |

| Weak | 4% | 14% | |||

| Not applicable | 4% | 11% | 29% |

Seven of the eight development effectiveness reviews examined provided positive assessments of the relevance of programming of the multilateral organizations assessed. These reviews included specific criteria that assessed relevance to target groups, which included beneficiaries, and thus the reports provided some analysis of this dimension of relevance. Many country program evaluations reviewed did not identify the exact needs of targeted beneficiaries, but overall, evaluators deemed the development interventions to be well aligned with targeted country priorities. Fifteen of the 18 country program evaluations described the overall relevance of country programs as strong.

The definition of relevance used by the Development Evaluation Division (PCE) differed from the definition used to assess the relevance of foreign affairs programming. In the latter, the Department included an emphasis on how programming was responsive to the needs of Canadians.. In the thematic and foreign affairs evaluation reports, 10 out of 14 focused on the needs and priorities of Canadians.

GAC’s programming targeted countries that were low income, middle income, as well as fragile states. However, programming evaluated in most country program, foreign affairs and thematic evaluations reviewed were not designed based on a country’s income and development status, with the exception of interventions in fragile states.

Relevance to reaching the poorest and most vulnerable

The evidence of Gs&Cs programming reaching the poorest and most vulnerable was mostly found in country program evaluations. Evaluation reports reviewed did not provide substantial insights on whether this happened consistently or whether this goal was being addressed appropriately; 16 of the evaluations reviewed made no mention of reaching beneficiaries considered to be vulnerable. Country program evaluations mentioned reaching the most vulnerable beneficiaries, but more often described reaching the poor, which was in line with Canada’s emphasis on poverty reduction. There was no consistent definition of how the poorest and most vulnerable were defined across the different types of departmental programming and, as a result, across the evaluation reports reviewed. Some reports described reaching “the poor and the marginalized”, while others described reaching “people underserved by the central government,” “underprivileged populations” or the “ultra-poor”. The development effectiveness reviews assessed whether programming met target group needs, not whether they reached the poorest and most vulnerable. Some of the reviews, such as for UNFPA and WFP, implied that the organization focused on the poorest and most vulnerable due to the nature of the mandate, particularly with regard to humanitarian, conflict and post-conflict settings.

However, for the 24 evaluation reports where programming addressed the poorest and most vulnerable, 63% had a strong rating for relevance and another 29% were acceptable.

Relevance to supporting fragile states

The relevance of programming to supporting fragile states was not often described in evaluation reports reviewed and was expected given that only a handful of countries were considered fragile states under the GAC definition. Relevance to fragile contexts was not explicitly discussed in foreign affairs or thematic evaluations as most of those reports did not carry out an assessment of relevance from the point of view of beneficiaries in the development context.

Of the 14 evaluation reports where programming supported fragile states, 57% had a strong rating for relevance and another 29% were acceptable.

Relevance to security and stability objectives

The review team also examined whether security and stability objectives Footnote 5 were addressed and found that 18 reports put some emphasis on security and 14 reports contained elements related to stability. Footnote 6 In most cases, these were not explicitly stated as objectives of the intervention, but could be implied from the nature of the program reviewed. Interestingly, both country program evaluation reports and foreign affairs evaluation reports contained information on stability and security. However, despite GAC’s current interest in security and stability objectives, neither programming, nor evaluations consistently addressed or described how they tackled these objectives. As a result, the Department does not have a conclusive body of evidence from evaluation reports on what works well to inform its future programming. Issues such as democratic transition, good governance, and protection of human rights were often associated with stability in evaluation reports (e.g., Canadian Fund for Local Initiatives evaluation). Specifically, 11% of evaluations that addressed security objectives and 29% of evaluations that addressed stability objectives could not be rated.

With these caveats, 44% of the evaluations that addressed security objectives had a strong rating and 44% had an acceptable rating. Similarly, 29% of the evaluations that addressed stability objectives also had a strong rating and 43% had an acceptable rating.

3.2.3 Contributing Factors

This review highlighted that the relevance of Gs&Cs programming was highly dependent on conducting appropriate needs assessment and situation analyses, engaging partners, and leveraging their respective strengths. These were the main contributing factors identified:

- Conducting appropriate needs assessment and consulting with potential beneficiaries and partners to align programs with target group members and national priorities, build consensus and leverage respective partner strengths (10/39 reports). For example, the Partnerships with Canadians Governance Program Evaluation emphasized that programs were most relevant when they involved local partners in needs assessment, strategy and proposal writing from the outset. This was considered essential to identifying risks and corresponding mitigation strategies.

- Building ownership and alignment through stakeholder engagement, more specifically with the involvement of stakeholders at design and implementation stages (5/39 reports). For example, the Caribbean regional program evaluation found that the program benefited from strong relationships and input from regional partners, in the areas of gender equality and governance.

- Establishing strategic partnerships with diverse groups of stakeholders (4/39 reports). For example, the Ukraine country program evaluation noted the involvement of an active and informed diaspora in country programming.

3.2.4 Limiting Factors

Although most evaluation reports provided a positive assessment of the relevance of programming, a few noted factors that limited the relevance of some interventions:

- Difficulties in conducting needs assessments due to reliance on poor or incomplete data (e.g., not stratified by sub-populations, such as gender, outdated data) or weak situation analyses (5/39 reports). This was noted in three country program evaluations, one development effectiveness review and one foreign affairs evaluation.

- Limited involvement of partners in the design and implementation phases that did not allow leveraging their knowledge, expertise and networks (4/39 reports).

3.3 Effectiveness of Gs&Cs Programming

3.3.1 Coverage of Effectiveness Criteria

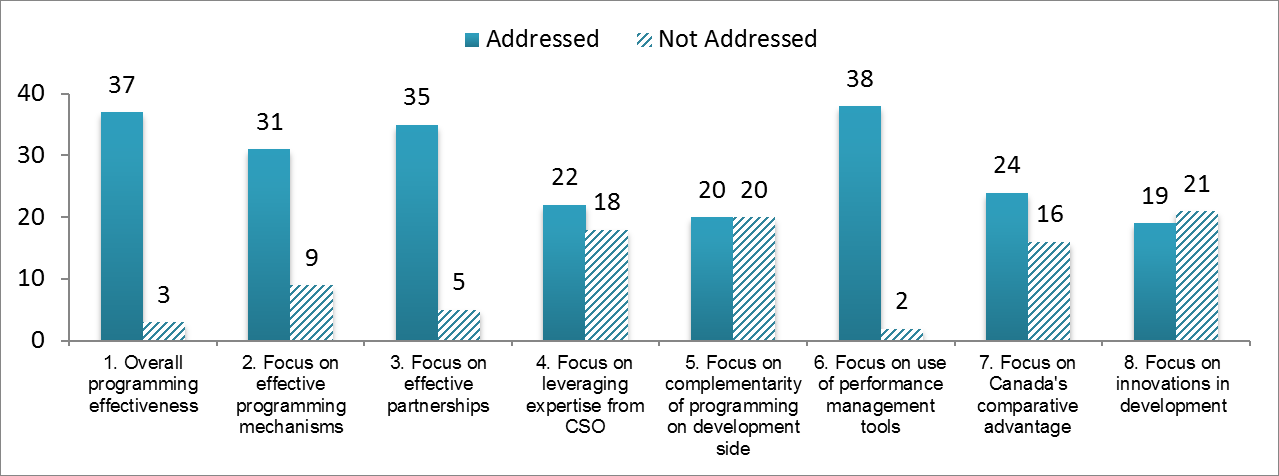

As shown in Figure 3.3 on the next page, coverage was high for the criteria that assessed overall program effectiveness, effectiveness of programming mechanisms, effectiveness of partnerships with traditional partners and use of performance management tools. Coverage of other criteria was significantly lower. Effectiveness of partnerships with non-traditional partners received little attention (2 reports).

Figure 3.3 Number of Evaluations that Addressed Effectiveness Criteria

Figure 3.3 - Text version

| Rating | 1. Overall programming effectiveness | 2. Focus on effective programming mechanisms | 3. Focus on effective partnerships | 4. Focus on leveraging expertise from CSO | 5. Focus on complementarity of programming on development side | 6. Focus on use of performance management tools | 7. Focus on Canada's comparative advantage | 8. Focus on innovations in development |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Addressed | 37 | 31 | 35 | 22 | 20 | 38 | 24 | 19 |

| Not Addressed | 3 | 9 | 5 | 18 | 20 | 2 | 16 | 21 |

3.3.2 Key Findings

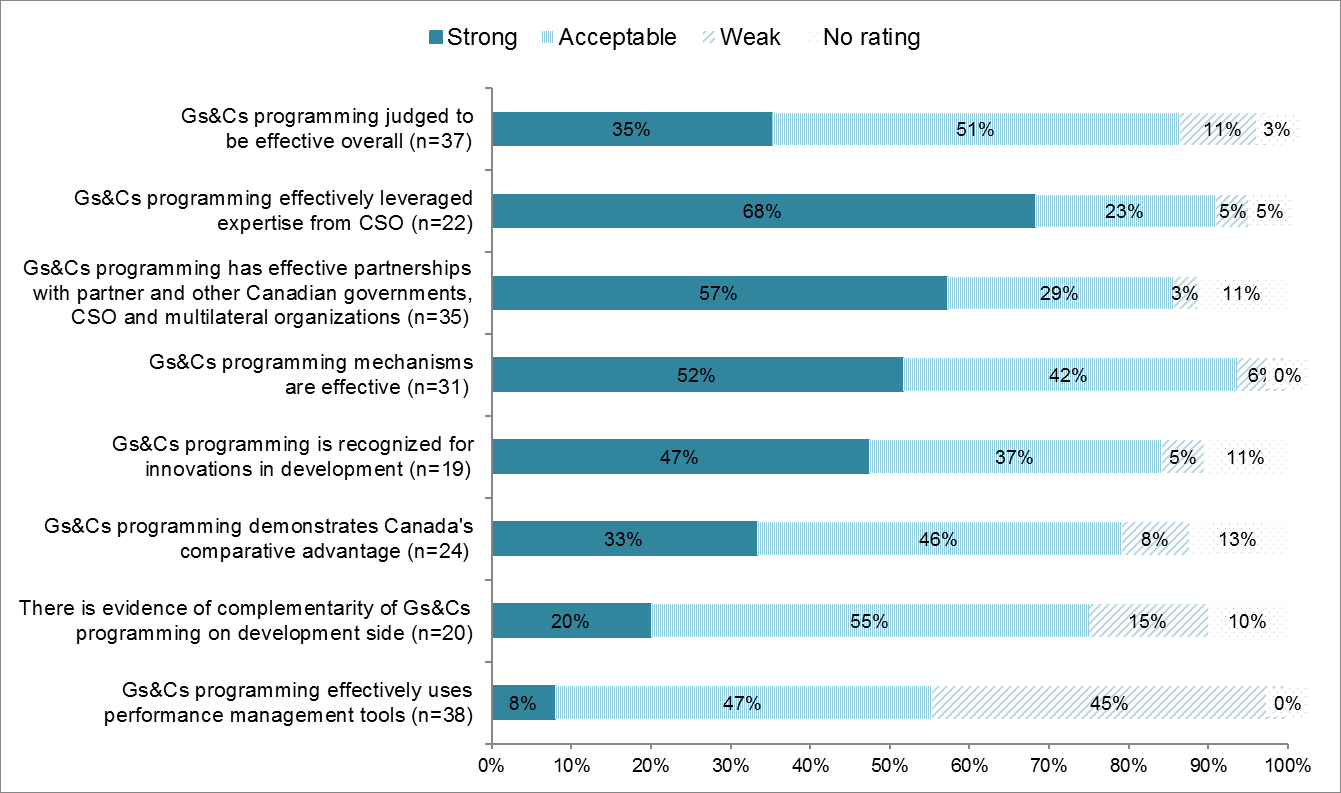

This section presents the assessment of how well Gs&Cs programming performed on effectiveness criteria and Figure 3.4 on the next page shows the ratings.

Overall Effectiveness

In terms of average ratings for each effectiveness-related question covered by the evaluation reports reviewed, most ratings were either strong or acceptable for overall effectiveness and for progress towards expected development outputs and outcomes. Only a few reports noted insufficient evidence to confirm program effectiveness. Most country program evaluations reported positive results at the project level in various sectors, although these tended to be focused on the achievement of outputs and immediate outcomes (i.e., short-term results).

Figure 3.4 Distribution of Ratings by Effectiveness Criteria

Figure 3.4 - Text version

| Rating | Gs&Cs programming judged to be effective overall (n=37) | Gs&Cs programming effectively leveraged expertise from CSO (n=22) | Gs&Cs programming has effective partnerships with partner and other Canadian governments, CSO and multilateral organizations (n=35) | Gs&Cs programming mechanisms are effective (n=31) | Gs&Cs programming is recognized for innovations in development (n=19) | Gs&Cs programming demonstrates Canada's comparative advantage (n=24) | There is evidence of complementarity of Gs&Cs programming on development side (n=20) | Gs&Cs programming effectively uses performance management tools (n=38) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strong | 35% | 68% | 67% | 52% | 47% | 33% | 20% | 8% |

| Acceptable | 51% | 23% | 29% | 42% | 37% | 46% | 55% | 47% |

| Weak | 11% | 5% | 3% | 6% | 5% | 8% | 15% | 45% |

| Not applicable | 3% | 5% | 11% | 0% | 11% | 13% | 10% | 0% |

Effective Leveraging of CSO Expertise

Most reports that addressed partnerships with CSOs provided a positive assessment of the program’s relationship with CSOs and received a strong rating with respect to the effective leveraging of CSO expertise (68%). In the context of fragile states, such as Afghanistan, using CSOs enabled access to certain populations but a disproportionate reliance on these organizations meant that linkages to national policies, strategies and implementation were often not sufficiently taken into account.

Effectiveness of Partnerships

In the reports reviewed, there was substantial evidence of diverse and strategic partnerships that added value to Gs&Cs programming. Partnerships with traditional partners, such as other Canadian government departments, national or sub-national governments in partner countries, CSOs and multilateral organizations, received strong or acceptable ratings (57% and 29%, respectively). The evaluation reports reviewed noted the existence of strong multi-stakeholder partnerships, with the evaluation reports on Afghanistan, Pakistan and Countries of Modest Presence providing particularly strong examples. Some evaluation reports mentioned that partnerships at different levels could be strengthened through enhanced coordination and communication (e.g., notably the foreign affairs evaluations of the Global Partnership Program, UNFPA and UNDP development effectiveness reviews and the Honduras country program evaluation).

Effectiveness of partnerships with non-traditional partners received little coverage. The two reports that provided information on non-traditional partners did not explicitly refer to these partners as non-traditional. The evaluation of the Canadian Police Arrangement mentioned work with policy services from three levels of government as bringing a new dimension to the whole-of-government approach. The evaluation of the Global Peace and Security Fund (2011) described a partnership with African Centers of Excellence to develop Africa’s peacekeeping training capacity.

Effectiveness of Programming Mechanisms

When assessed, the effectiveness of programming mechanisms was rated as either strong (52%) or acceptable (42%). Programming mechanisms were not always assessed individually in the evaluation reports; however, reviewer observations indicated it was the mix of programming mechanisms used to implement various projects in each program portfolio that contributed to overall program effectiveness. In the context of country program evaluations, the complementarity and flexible aid delivery resulting from combined mechanisms were identified in various evaluation reports as a factor contributing to success.

Innovation

Recognition of Canadian innovations in development was, on average, rated as strong (47%) or acceptable (37%). The majority of innovations identified in country program evaluations were in governance sector programming, followed by the agriculture and environment sectors. Some innovations were also reported in the gender equality, education and health sectors. Innovations covered a broad range of initiatives in each of the sectors identified. Of note, most of the innovations in the governance sector were reported from countries of modest presence that had lower middle income status.

Canada’s Comparative Advantage

Canada’s comparative advantage was examined in 60% of evaluations reports. Of those, 33% assessed this area as strong and another 46% as acceptable. Most examples provided in reviewed evaluations concerned areas of gender equality and policy dialogue. Despite the limitations associated with RBM noted below, several reports (e.g., Peru country program evaluation, UNFPA and UNICEF development effectiveness reports) indicated that Canada’s promotion of RBM represented a distinct advantage among other donors and partners.

Complementarity of Programming

Only 20% of evaluation reports assessed complementarity of Gs&Cs programming as strong. A number of country program evaluations highlighted weaknesses in inter-program complementarity and synergies (e.g., the Inter-American Program, Colombia, Caribbean, Honduras, Haiti, Bolivia, Senegal, Mozambique-Tanzania). This appeared to be related to weak information dissemination or knowledge sharing among programs, including sharing regional trends, sectoral opportunities, results, lessons and good practices from different initiatives. This information was not readily available to other programs and projects that could benefit from it.

In the development effectiveness reviews, among the recurring challenges for the Department with regard to institutional support through the multilateral channel, were developing a strategy for engagement with the multilateral organizations that was known throughout the Department; and creating linkages between Canada's work at the Executive Board and in other parts of the Department. The objectives for institutional engagement were not always followed up with specific funding, yet in some cases (e.g., UNFPA) there was an expectation that it would be. This suggests a need to strengthen program coherence for development programming among the Multilateral, Geographic Programs, and Partnerships for Development Innovation Branches. To this effect, the Peru country program evaluation report suggested developing a liaison mechanism. In fragile states such as Haiti and Afghanistan, reports noted challenges in the integration of humanitarian assistance and development programming.

Complementarity between development and foreign affairs programming was discussed in a small number of evaluation reports, but appears to be more evident since the amalgamation of CIDA and DFAIT. Consultations with the Department suggested that complementarity between initiatives focused on security and on development was not always feasible given the distinct objectives and contexts of each. However, some of the evaluations suggested that there was room for improvement. Specifically, the evaluation of the Global Partnership Program (2015) noted a lack of coordination among the Department’s security and development programming in several Canadian missions abroad. The evaluation of the Global Peace and Security Fund referred to committees established to ensure that activities between foreign affairs and development did not overlap. However, these committees did not meet regularly and did not transfer information back to their respective agencies to help ensure that overlap did not occur.

Finally, evaluations spoke favourably of efforts to seek complementarity with other development partners. Canada participated actively in multi-donor working groups and discussion fora in several countries. These donor coordination mechanisms were used to strengthen coordination and aid effectiveness and to avoid duplication of efforts among stakeholders.

Use of Results-based Management Tools

Various results-based management (RBM) tools were used in evaluated Gs&Cs programming to monitor and report on results and manage risks. Results-based management was somewhat inconsistent at the project level and was generally scant and in some cases non-existent at the program level. The ratings for results-based management are almost evenly split between acceptable (47%) and weak (45%). Footnote 7

Several country program evaluation reports noted weaknesses in program-level reporting on the results achieved, largely due to performance measurement limitations, such as lack of Performance Measurement Frameworks, targets, baseline data, or ineffective monitoring and evaluation, which made reporting on higher-level program results difficult. The following observations were based on an analysis of the evaluations of Bangladesh, Bolivia, Pakistan, Indonesia, Senegal, Caribbean Regional Program, and Countries of Modest Presence:

- At the project level: RBM tools were commonly used but the quality of results measurement and reporting was uneven, especially at the higher levels of expected results (e.g., intermediate outcomes). Reports noted a lack of baseline data, weak or inappropriate indicators in particular. Assessment of project effectiveness was further complicated by the limited number of evaluations undertaken at the project level.

- At the program level: While Performance Measurement Frameworks for country programs were not a corporate requirement until 2009, several programs developed and implemented frameworks before this became a requirement. These frameworks, as well as those produced after 2009, however, showed weaknesses such as lack of baseline data and weak or inappropriate indicators. Weaknesses at the program level were also affected by changing corporate reporting tools and lack of coherence or harmonization between project- and program-level expected results. Some reports also noted that current frameworks did not adequately capture unexpected/unplanned results (e.g., policy dialogue, donor coordination). Performance measurement at the program level depended in large part on data aggregated from various projects, and in many cases, the collection of project-level data was not planned for or budgeted or was limited to project activities and outputs.

- Multilateral implementation: Some lack of harmonization between GAC’s RBM requirements and those of other donors (other governments, international organizations) presented a challenge to implementing agencies and resulted in difficulties in reporting on results at both project and program level.

As with bilateral programming, assessment of the effectiveness of Gs&Cs programming through the multilateral channels was affected by limitations in results-oriented planning, monitoring and reporting in multilateral organizations. Development effectiveness reviews noted that the programming of multilateral organizations was often ambitious, with objectives that lacked causal linkages, had poorly framed indicators and lacked baseline information. The reviews, notably of the UNFPA, UNICEF and IaDB that contained a section on Canada’s Management Practices, also reported that institutional engagement strategies were rarely accompanied by a Performance Measurement Framework to monitor and report on the Department's strategic engagement with the multilateral organizations. The Department was aware of this limitation and was piloting a Performance Measurement Framework with one of its new institutional engagement strategies.

While the practice of RBM was reflected in development programming and evaluations, the same practice was not evident in the foreign affairs evaluations. This could be attributed to the nature of the foreign affairs programming, which was often reactive and addressed immediate concerns in fragile circumstances where humanitarian assistance or military interventions were necessary. Ex-ante RBM designs were not feasible under such circumstances, nor were ex-post measurements. It may be useful to develop a generic Performance Measurement Framework that could be applied to measure contributions in this area of GAC’s mandate.

Consultations with stakeholders in the Department confirmed that the application of RBM remains a challenge. A small team of RBM experts within the RBM Centre of Excellence, together with RBM advisors (known as Program Management Advisors) located within operational branches provide technical assistance to more than 1,000 international assistance projects implemented by the Department this year. These projects are implemented by more than 800 different partners who all need to understand GAC’s expectations in relation to RBM. A guide on how to integrate RBM in international assistance programming is currently being developed.

During the consultations for this review, other factors that affected the use of RBM emerged. These included: the lack of an enabling environment in the Department (e.g., insufficient time to apply RBM during the planning, design and approval stages and insufficient time or resources to manage for results, lack of experience in formulating outcomes); different levels of RBM maturity within former CIDA and DFAIT; the lack of planning and budgeting to collect performance data; and high staff turnover within the Department. Footnote 8

3.3.3 Contributing Factors

The evaluation reports reviewed pointed to the following factors influencing the success of Gs&Cs programming:

- Utilizing strong knowledge, expertise, and skills of GAC and partner human resources (other Canadian government department personnel, Canadian and local staff and volunteers, staff from implementing agencies, external experts) (16/37 reports). Notable areas mentioned in the evaluation reports were expertise in gender equality, expertise in international trade issues, new technology, and agriculture that contributed to the effectiveness of programming (Senegal and Ukraine country program evaluations).

- Partnering with multiple sector representatives (public, private, community, CSO) (13/37 reports). For example, the evaluation of Development Programming in former Countries of Modest Presence noted that building on successful previous initiatives with trusted government, NGOs or multilateral partners, strategic policy dialogue and appropriate coordination with other donors contributed to program effectiveness in these countries. The Pakistan country program evaluation also highlighted innovative partnerships with public, private and community-based entities.

- Building capacity in RBM and monitoring and evaluation for stakeholders as well as using appropriate RBM tools and conducting systematic monitoring and evaluation (11/37 reports). The Caribbean Regional Program evaluation commented positively, for example, on the clarity of logic models and the precision and suitability of performance indicators and processes put in place in implementing agencies and within CIDA to measure and monitor progress on results.

- Effectively leveraging CSO expertise, both Canadian and local (9/37 reports). With respect to local CSOs, the Partnerships with Canadians Governance Program evaluation noted that local partners had valuable contextual knowledge of culture and governance realities that helped identify interventions which were most likely to work in that specific context. Local partners understood the needs in their community and facilitated reaching across different societal layers to increase the participation of community members.

- Ensuring that type, size and scale of programs was appropriate in relation to country and beneficiary needs (6/37 reports). This was emphasized in the UNICEF development effectiveness review.

- Decentralizing program management from headquarters to field offices (6/37 reports). This was mentioned notably in the context of Central and South American countries.

- Managing funds locally to pilot new initiatives and foster innovation (6/37 reports).

- Using a mix of program mechanisms and flexible implementation at project level that allowed to adjust to changing circumstances and emerging opportunities (5/37 reports). The Afghanistan country program evaluation highlighted the flexibility of implementation at project level in particular.

Limiting Factors

The following factors contributed to some of the unsatisfactory evaluation findings in the area of programming effectiveness:

- Limited engagement of national partners and their weak institutional capacity (17/37 reports). For instance, the development effectiveness review of the Inter-American Development Bank noted a lack of political interest and country ownership of some Bank-supported development projects and programs. Weak institutional capacity was noted in the three fragile state program evaluations reviewed.

- Weak communication and knowledge sharing among key stakeholders, such as donors, Canadian and other country government departments (13/37 reports). The evaluations that reported weaknesses in program design also tended to report weaknesses in communication and knowledge sharing.

- Weaknesses in the development of RBM tools (logic models, Performance Measurement Frameworks) at the program and project levels (13/37 reports). The Bolivia country program evaluation was representative of some of the common issues documented by evaluators: the existing Performance Measurement Framework did not provide a clear overview of planned results and measurable indicators; baseline data were not established and risk management was somewhat weak; at the project level, some outcome statements were too ambitious and lacked realistic indicators; there were inconsistent monitoring requirements from one project to another with some project reports focusing more on activities and outputs than on results achieved.

- Lack of aggregated performance measurement data at the program level, which were fed from projects, with inadequate baseline data collection, risk management and monitoring of activities and outputs (8/37 reports).

- Some lack of guidance and limited technical support and resources available to program staff in the application of RBM and use of corporate reporting tools (5/37 reports).

- External factors, such as political turmoil, natural disasters and humanitarian crises, particularly in fragile states, were frequently highlighted (13/37 reports). In addition to the volatile situation in fragile states, examples from the countries of modest presence included a drought in Nicaragua, hurricanes in Cuba, the influx of Syrian refugees in Jordan and the revolution in Egypt.

3.4 Efficiency of Gs&Cs Programming

Coverage of Efficiency Criteria

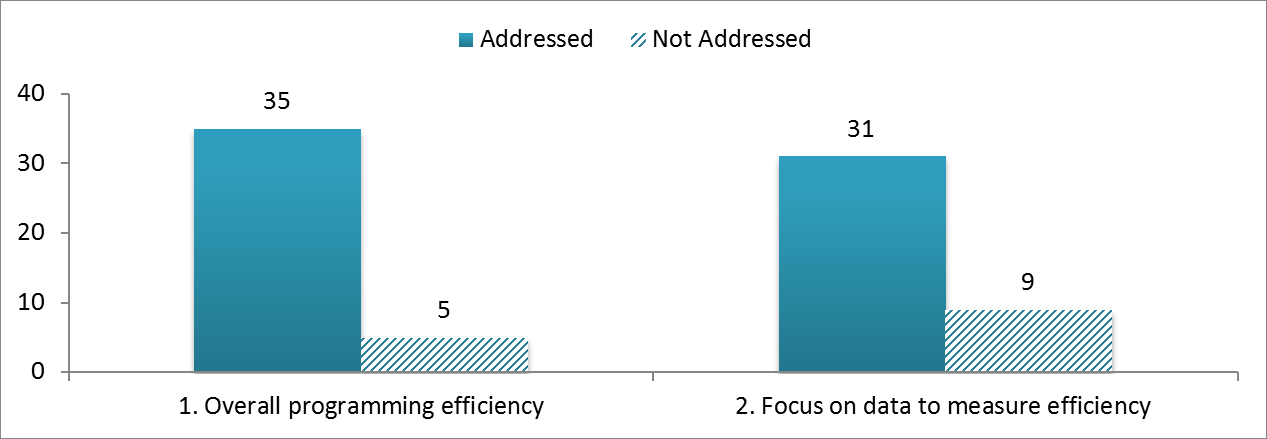

The evaluation reports reviewed generally addressed efficiency criteria (Figure 3.5). Most (88%) drew conclusions on programming efficiency and 76% generated information, qualitative mostly, to measure efficiency.

Figure 3.5 Number of Evaluations that Addressed Efficiency Criteria

Figure 3.5 - Text version

| Rating | 1. Overall programming efficiency | 2. Focus on data to measure efficiency |

|---|---|---|

| Addressed | 35 | 31 |

| Not Addressed | 5 | 9 |

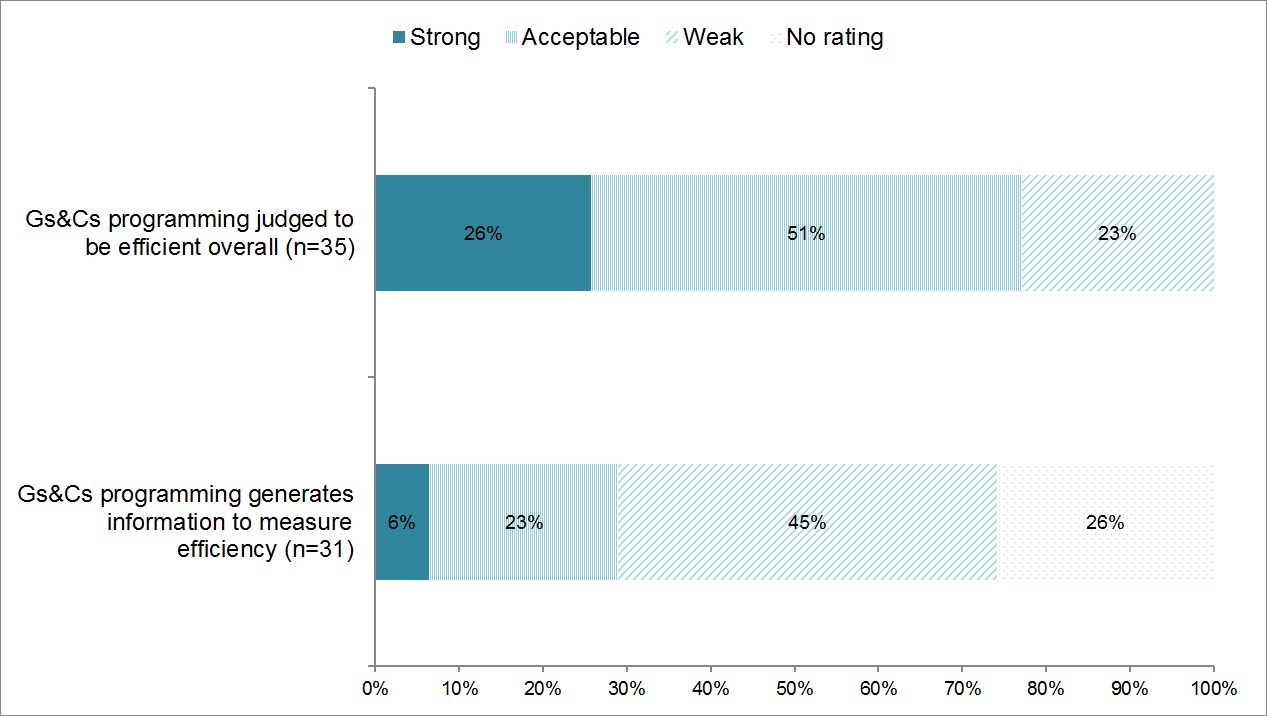

3.4.2 Key Findings

Overall Efficiency

The number of evaluation reports that rated the overall efficiency of Gs&Cs programming as strong and as weak was split fairly evenly. Specifically, 26% of the evaluations reported strong ratings for efficiency and 23% had a weak rating. Of concern, only 6% of the evaluation reports had a strong rating for the generation of information to measure efficiency. These numbers suggested that the Department faced challenges in clearly demonstrating the efficiency of its Gs&Cs programming.

Figure 3.6 Distribution of Ratings by Efficiency Criteria

Figure 3.6 - Text version

| Rating | Gs&Cs programming judged to be efficient overall (n=35) | Gs&Cs programming generates data to measure efficiency (n=31) |

|---|---|---|

| Strong | 26% | 6% |

| Acceptable | 51% | 23% |

| Weak | 23% | 45% |

| Not applicable | 0% | 26% |

One of the main observations of this review was that the Department did not have a common set of criteria or approaches to assess efficiency across programs, which made it difficult to draw comparisons across types of programming or to trace good practices. Footnote 9 While it might not be feasible to have common efficiency criteria across all types of programming, it may be helpful to identify standard criteria by groupings (e.g., specific standards for assessing the efficiency of country programs, for example). Country program evaluations and development effectiveness reviews could use similar determinants to assess efficiency related to timeliness, allocation of resources relative to results achieved, or whether and how monitoring information is used to inform program implementation.

In the case of country program evaluations and foreign affairs programming, a number of factors that limited efficiency were under the direct control of the Department. These factors concerned the need to maintain stable workforce and avoid high staff turnover within the Department and streamlining approval authority. Further, the review highlighted that development programming and foreign affairs programming continued to operate distinctly after amalgamation, which was described as a limitation to programming efficiency. The number of processes for program design, implementation, monitoring and reporting that existed for programs and projects was high and was not yet consolidated following the amalgamation of CIDA and DFAIT. Finally, Performance Measurement Frameworks did not typically capture information to assess and monitor efficiency. Systems to collect data on costs per beneficiary were not designed upfront and no guidance was available in the Department on how to address measuring efficiency.

Multilateral organizations assessed in development effectiveness reviews received mixed ratings on efficiency; fewer than half of those reviews (3 out of 8) provided satisfactory ratings on efficiency. Multilateral organizations faced some of the same challenges faced by the Department. Many multilateral organizations lacked consistent data on efficiency indicators, such as costs of outputs, or were affected by the lack of timeliness of program delivery (often due to cumbersome administrative procedures). The UNICEF report stated that the most frequently cited factor impeding the cost and resource efficiency of UNICEF-supported programs was the lack of appropriate cost data reported regularly and on time to allow for a reasonably accurate calculation of services costs. Footnote 10 The fragmentation of programming in many multilateral organizations also seemed to undermine efficiency. In terms of Canada's engagement with the multilateral organizations, Canada was usually described as being responsive to the organizations, but on some occasions, especially during the period of the amalgamation of the departments (2013-2014), there was some lack of clarity about who took decisions on funding, and therefore a lack of timely response on funding requests (e.g., UNFPA, IaDB). The development effectiveness reviews also pointed to the need to ensure more regular and systematic communication between multilateral and bilateral programs (e.g., UNFPA, UNICEF).

In terms of departmental administrative processes, the evaluation of the Office of Religious Freedom/ Religious Freedom Fund explicitly referred to the Authorized Programming Process (APP). Footnote 11 It found that APP selection mechanisms were equal to or faster than non-APP mechanisms for approval and that the level of effort was only slightly higher for program staff.

Information to Measure Efficiency

The review highlighted a significant lack of quality data available to assess this criterion. Specifically, 26% of evaluation reports did not present any information with respect to this criterion and 45% were assessed as weak. Where efficiency was addressed it was commonly informed by qualitative evidence, such as interviews with various stakeholders.

Twenty reports identified the lack of financial data as an impediment to providing a complete assessment of efficiency. Although Gs&Cs programming generated some data to measure efficiency, data were often incomplete or insufficient to provide a full picture of how resources were spent. Assessing costs by unit value were not commonly planned for at the design stage and were not collected. Consulted stakeholders also noted that providing a cost per unit value was more feasible for some type of programming than others (e.g., a program providing inoculation than programming focused on humanitarian action or political change).

3.4.3 Contributing Factors

Reports commented on factors that contributed positively to efficiency of Gs&Cs programming:

- Relying on appropriate human resources to ensure successful program and project implementation. Leadership, dedication and flexibility demonstrated by field teams and knowledge and expertise of human resources and consultants (local and international) were identified as examples (14/35 reports). The Pakistan country program evaluation, for example, noted good use of local resources in education and women’s economic empowerment sector programming. The Tanzania program benefited from hiring of specialized staff with health expertise and public finance management expertise who provided technical support to the program, the government of Tanzania and other donors. The UNICEF development effectiveness review highlighted the strong management and programming capacities of UNICEF Country and Regional Offices.

- Using sound management practices, such as decentralized management and flexible design to facilitate timely action and adjustments, when necessary (6/35 reports). For example, evaluators noted that the decentralized management of the Maternal, Newborn and Child Health Initiative contributed to its efficiency, and the Peru country program evaluation noted that flexible design and management allowed for timely action and budgetary adjustments to be made during implementation.

- Engaging local or specialized institutional partners (4/35 reports). The Honduras country program evaluation reported more efficient programming among projects managed by executing agencies or by local or specialized institutions, compared to those managed by central institutions in countries.

Although previous studies and analyses conducted by the Department did not focus heavily on efficiency, flexibility was sometimes highlighted as one of the factors leading to improved efficiency of programming (e.g., CIDA Learns: Lessons from Evaluations 2012). This was most apparent when programming was decentralized as it offered additional opportunities to transfer responsibilities to partners in the field allowing greater flexibility in terms of adaptation to specific local circumstances.

3.4.4 Limiting Factors

Many reports reviewed commented on the challenges in collecting quantitative financial information required to assess efficiency. Other obstacles to efficiency included:

- Lengthy decision-making and approval processes, coupled with a lack of devolution of authority or predictability in the allocation of funds (17/35 reports).

- High management or administrative costs for some programming, particularly when implementation was scaled down from the initial plan (5/35 reports). The overhead ratio was generally higher for small and/or geographically dispersed initiatives. For example, the Canada Fund for Local Initiative (CFLI) evaluation reported high administrative fees of 20% in relation to program disbursements. Footnote 12 Only one country program evaluation (Indonesia) mentioned concerns about high proportionate costs for management and international technical expertise.

3.5 Sustainability of Gs&Cs Programming

3.5.1 Coverage of Sustainability Criteria

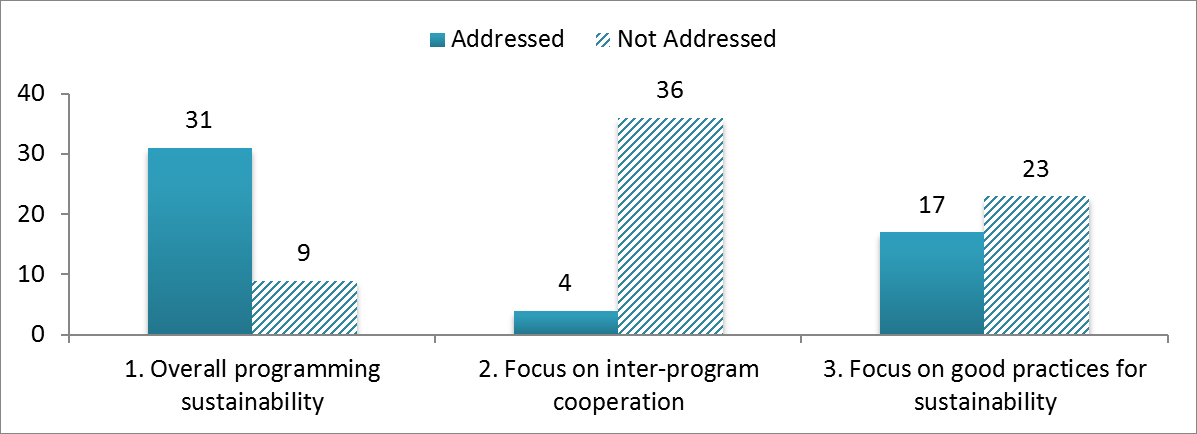

While coverage of program sustainability was high overall (78%), many reports assessed the area qualitatively, commenting on the prospects for sustainability and not on the level of sustainable results achieved. Less than one-half (43%) addressed good practices for sustainability and a small number of reports (10%) examined the impact of inter-program cooperation on sustainability (Figure 3.7).

Figure 3.7 Number of Evaluations that Addressed Sustainability Criteria

Figure 3.7 - Text version

| Rating | 1. Overall programming sustainability | 2. Focus on inter-program cooperation | 3. Focus on good practices for sustainability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Addressed | 31 | 4 | 17 |

| Not Addressed | 9 | 36 | 23 |

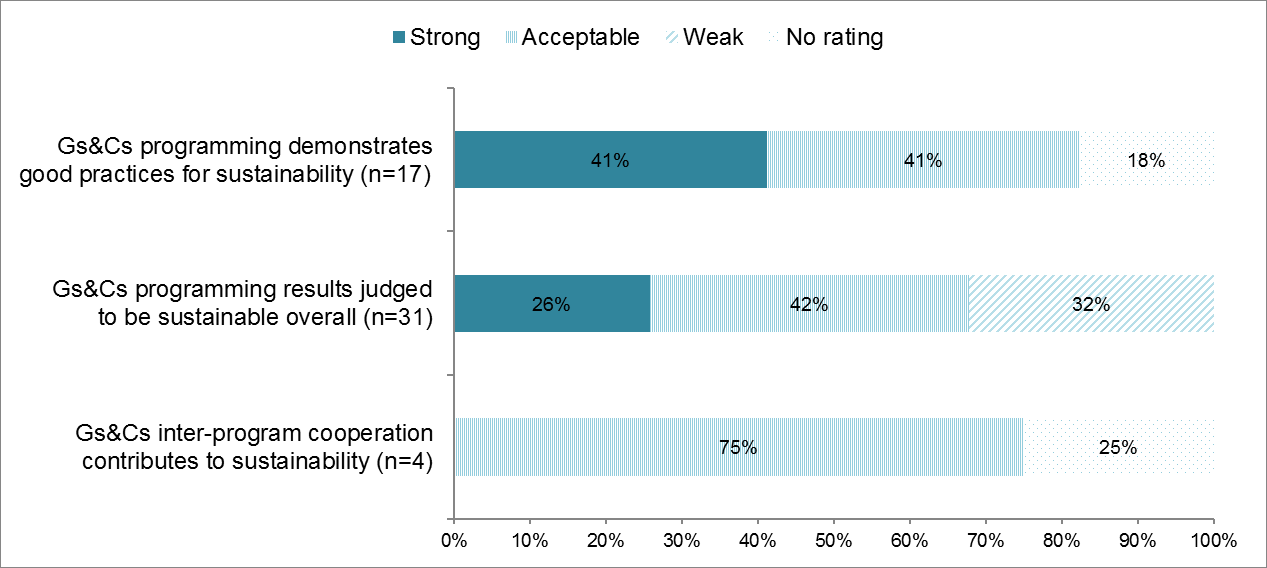

3.5.2 Key Findings

In terms of overall sustainability, the most common rating was acceptable (42%). However, there were significant variations in individual report ratings for sustainability and a significant proportion was assessed as weak (32%). Of note, given that the time passed after completion of many of the programs and initiatives was too limited to allow for the full assessment of sustainability of results, evaluations generally drew conclusions on the prospects for sustainability rather than concluding on the level of sustainability actually achieved.

Figure 3.8 Distribution of Ratings by Sustainability Criteria

Figure 3.8 - Text version

| Rating | Gs&Cs programming demonstrates good practices for sustainability (n=17) | Gs&Cs programming results judged to be sustainable overall (n=31) | Gs&Cs inter-program cooperation contributes to sustainability (n=4) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strong | 41% | 26% | 0% |

| Acceptable | 41% | 42% | 75% |

| Weak | 0% | 32% | 0% |

| Not applicable | 18% | 0% | 25% |

In the 31 reports that addresses sustainability, approximately half of the programming evaluated showed good prospects for sustainability. The majority of the evaluated programs contributed to strengthening the enabling environment for development. Evaluations of country programs often illustrated ownership of results at the country level, which boded well for sustainability, but there was limited concrete evidence of sustained results in the reports reviewed.

While there was limited evidence of good practices for sustainability, a few elements that emerged from the review team’s analysis in addition to the contributing factors outlined below were: skills transfer and training sessions on best practices adapted to country situations in various sectors (e.g., agricultural production and environmental protection in Haiti and West Bank and Gaza); building strong ownership at the local level; and planning for sustainability early in project/program implementation, for example by ensuring early buy-in from local governments and key stakeholders.

3.5.3 Contributing Factors

Evidence from the reports indicates the following factors enabled the sustainability of results:

- Engaging and building ownership with country partners, including government and local organizations (15/31 reports). This was highlighted in almost all development effectiveness reviews and in a number of country program evaluations, with a particular focus on the early engagement from the program’s or initiative’s onset.

- Building relationships and networks among key stakeholders at all levels (8/31 reports). For example, the Mali country program evaluation noted that CIDA's participation through the program-based approach in all sectoral consultation frameworks, promotion of information sharing and complementarity of effort were conducive to results sustainability. The Inter-American Program country program evaluation stated that overall prospects for sustainability of program results were strong by virtue of the program’s choice of regional partners, i.e., all partners were well established within the region, most showed strong connections to their key constituency groups, and many demonstrated high or improving levels of management competency.'' Footnote 13

- Embedding change in institutions, namely through capacity building activities (6/31 reports). The Honduras country program evaluation positively acknowledged local and regional-level capacity building which lead to significant human capital gains over the medium and long terms. The Meta-Synthesis of Evaluations on Selected Policy Themes (2015) suggested that building capacity and changing attitudes required a long-term commitment and multiple interventions.

- Ensuring strong alignment with country needs and priorities (5/31 reports). Some country program evaluations drew a parallel between the sustainability of results achieved and relevant programming that was in tune with country and beneficiary needs and priorities.

There was limited evidence of the contribution of inter-program cooperation to sustainability, but some noteworthy examples emerged from the Egypt and Nicaragua country programs evaluated in the context of the countries of modest presence:

- In Egypt, the report noted: “A key value added from Global Affairs Canada programming was its longstanding dedication to establish strong, diverse and strategic partnerships between donors, governmental bodies, and civil society. The country program held meetings for Canadian-funded projects between beneficiary micro, small, and medium enterprises and donors that allowed for donor mapping exercises, gap identification and tangible collaboration. Convening development stakeholders was an approach also adopted by government representatives as a successful model for bilateral and multilateral coordination.” Footnote 14

- In Nicaragua, the Department’s program targeted initiatives in the Northern region of the country that “created synergies between integrated watershed management, improved agricultural practices for young farmers and the electrification of more than 500 communities, to increase sustainable economic growth primarily through agriculture.'' Footnote 15

3.5.4 Limiting Factors

The reports also pointed to the following factors limiting the sustainability of results:

- Lack of institutional capacity and/or commitment from partner countries’ governments to maintain results (17/31 reports). While the Peru country program evaluation noted the lack of managerial capacities and frequent staff turnover in public institutions, the evaluation of the Caribbean Regional Program stressed that institutional weaknesses were more acute with small states which had a limited absorptive capacity. This was also highlighted in the Analysis of Common Themes Emerging from Corporate Development Evaluations (2015) that pointed to limited capacities of partner and beneficiary countries and short timelines for implementation of projects hindering the sustainability of many projects.

- Insufficient planning for sustainability, e.g., through exit strategies, adequate resourcing for a phasing-out period (6/31 reports) and placing a disproportionate emphasis on generating short-term results at the expense of a longer-term strategic focus (7/31 reports). This factor was noted primarily in the context of four development effectiveness reviews and also country program evaluations. For example, in fragile states, like Afghanistan and Haiti, evaluators noted that short-term implementation strategies sped up project delivery considerably but failed to ensure sustainable, long-term development results in several areas. The evaluation of the Global Partnership Program stated the program was largely focused on the delivery of short-term results, such as equipment and training, with more than half of projects completed in a year or less.

- Lack of recurrent funding mechanisms for infrastructure and serviced delivery projects (14/31 reports). For example, the development effectiveness reviews noted that infrastructure projects, such as road projects, suffered from insufficient funding and institutional capacity to ensure periodic and routine maintenance. This was also related to paying insufficient attention to scaling up or replicating successful projects.

- External factors, such as natural disasters, political turmoil, violence and conflict, as well as corruption, were acknowledge in a number of reports (6/31 reports). The sustainability of field operations was jeopardized, for example, by violence and conflict in countries, such as Colombia, specifically the Department of Nariño where much of the programming was focused, and Mali that experienced unrest in the northern region.

3.6 Integration of Cross-Cutting Themes in Gs&Cs Programming

3.6.1 Coverage of Cross-Cutting Theme Criteria

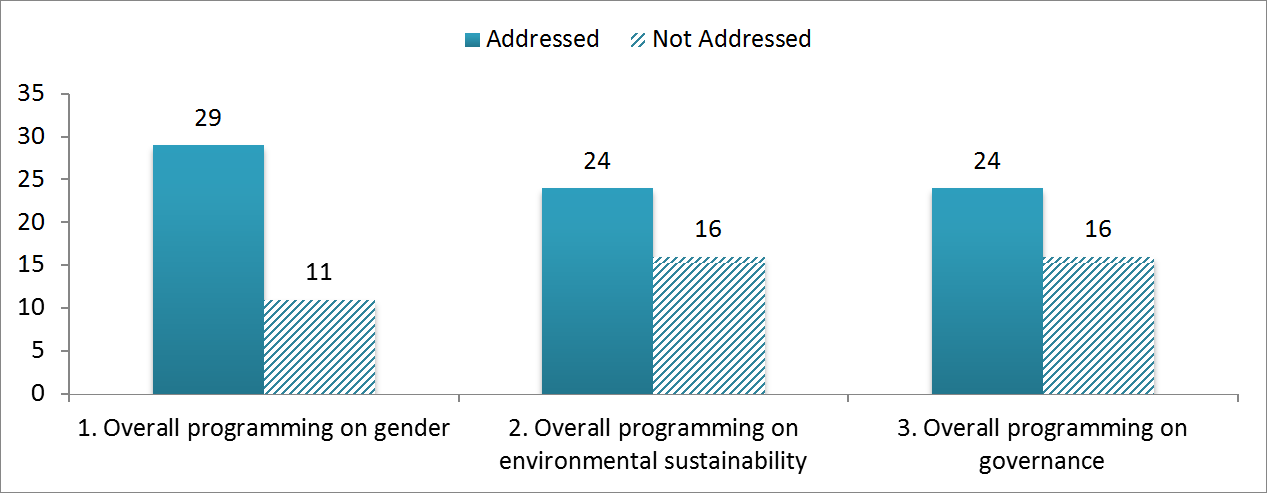

GAC has three cross-cutting themes that must be addressed and integrated in all development programming (gender equality, environmental sustainability and governance). Figure 3.9 shows the number of evaluation reports that addressed each cross-cutting criterion.

Figure 3.9 Number of Evaluations that Addressed Cross-Cutting Themes Criteria

Figure 3.9 - Text version

| Rating | 1. Overall programming on gender | 2. Overall programming on environmental sustainability | 3. Overall programming on governance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Addressed | 29 | 24 | 24 |

| Not Addressed | 11 | 16 | 16 |

Gender Equality: The theme of gender equality was addressed in 73% of the evaluation reports reviewed. A few country program evaluations identified gender equality both as a cross-cutting theme and as a program priority. Development effectiveness reviews of multilateral organizations indicated poor coverage of gender equality in several multilateral organizations (e.g. UNICEF, IDB, and WFP), though some recently began implementing new gender policies. The UN-System Wide Action Plan on gender equality and empowerment of women was only introduced in 2012.

Environmental Sustainability: While 60% of reports reviewed addressed environmental sustainability, only half of the reports that addressed this theme also explicitly incorporated information on the impacts of climate change. Environmental sustainability and climate change were often not covered by the development effectiveness reviews.

Governance: This theme was addressed in 57% of reports reviewed. Eight reports addressed governance solely as a program sector with no cross-cutting integration as these evaluations likely covered initiatives that preceded the departmental policy requirement that governance be considered a cross-cutting dimension of programming. Coverage of governance was particularly strong in 8 of the 18 country program evaluations reviewed, where governance was identified as both a program priority sector, e.g., in education or health, and a cross-cutting theme.

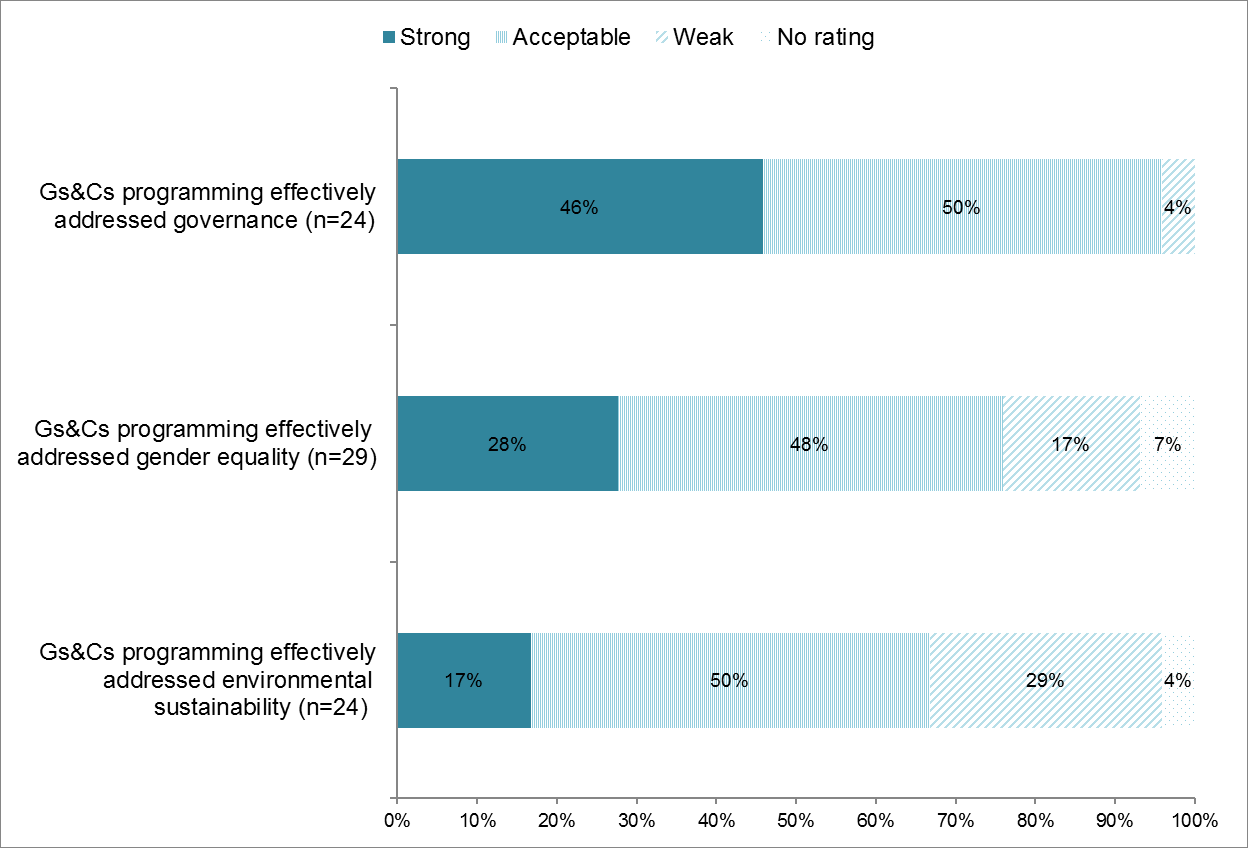

3.62 Key Findings

Evaluations of Gs&Cs programming did not consistently address cross-cutting themes, but where addressed, the majority of programs were rated as acceptable or strong (Figure 3.10).

Figure 3.10 Distribution of Ratings by Cross-Cutting Theme Criteria

Figure 3.10 - Text version

| Rating | Gs&Cs programming effectively addresses governance (n=24) | Gs&Cs programming effectively addresses gender (n=29) | Gs&Cs programming effectively addresses environmental sustainability (n=24) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strong | 46% | 28% | 17% |

| Acceptable | 50% | 48% | 50% |

| Weak | 4% | 17% | 29% |

| Not applicable | 0% | 7% | 4% |

Six country program reports Footnote 16indicated that the cross-cutting themes were not fully captured in programming. In part, this appeared to be linked to limitations of applying a results-based management framework to identifying, measuring and monitoring the results associated with cross-cutting themes. Reports highlighted difficulties experienced by implementing agencies on how to integrate the themes operationally in logic models and Performance Measurement Frameworks, as well as challenges in understanding the Department’s expectations. Additional corporate guidance and technical support for the integration of gender equality, environmental sustainability, and governance, at project and program levels may help address these issues.

Gender Equality

Ratings for gender equality were generally acceptable, with 28% of evaluation reports showing a strong rating and 48% showing acceptable. Of note, 17% were assessed as weak and another 7% could not be rated due to the lack of evidence presented in evaluation reports.

While Canada has been recognized for its leadership in promoting gender quality dialogue and policy, the review observed a diminishing focus in programming in this area over time. Several country program evaluations reviewed (e.g., Indonesia, Mali, Countries of Modest Presence) noted a diminishing focus on gender equality over evaluation periods, while others (e.g., Caribbean, Ukraine) mentioned the elimination of Gender Equality Funds and limited availability of gender equality specialists to provide support with the integration of this theme in programming. Footnote 17 It was not clear whether these factors were a consequence of less corporate investment in gender equality over time, decentralization of programs and technical support from headquarters to the field, or whether it was a reflection of the maturity of the country in terms of progress towards an enabling environment for gender equality.

Among the eight multilateral organizations assessed through the development effectiveness reviews, UNFPA and UNDP received a positive assessment in terms of their implementation of gender equality principles. The other organizations either had insufficient information on, or coverage of, gender equality in their own evaluations, with only UNICEF rated as weak on gender equality integration. The latter was noted in the report as “surprising given that addressing gender equality represents a “foundation strategy” for UNICEF programming.” Footnote 18

A previous meta-synthesis of GAC evaluations on selected policy themes Footnote 19 also highlighted the challenge of having sustained capacity to address gender equality in programming. It indicated a need to develop capacity for gender equality integration and analysis within the Department, to ensure that projects had professional gender equality specialists available and to budget for these resources. The report further stressed that gender equality was often identified as a policy dialogue priority and was not always assigned a commensurate level of funding for programming.

Environmental Sustainability

Although environmental sustainability was addressed in 24 evaluation reports, evidence of its integration in programming was not sufficiently robust to draw conclusions on effectiveness in most instances. Only 17% of evaluations reviewed received a strong rating in this area, while 29% received a weak rating.

The development effectiveness reviews provided little information on how multilateral organizations addressed environmental sustainability (including climate change) and the extent to which Canada advocated for emphasis in these areas was not clear. The one exception was the UNDP review which reported that UNDP was effective in supporting environmentally sustainable development in several areas, such as enhancing national energy policies, improving rural and urban water resource management; strengthened conservation programs and improved promotion of bio-diversity and improved natural resource management capacity.

In foreign affairs programming, the evaluation of the Global Partnership Program found that environmentally sound nuclear disposal methods were implemented by Canada and its partners. For instance, the successful dismantlement of nuclear submarines by Canada, in cooperation with the United States and Russia, meant that a serious proliferation threat was contained and the environmental threat to the shores of Canada and other Arctic neighbours was reduced.

The country program evaluations generally indicated that environmental sustainability was not a major programming theme and tended to be integrated primarily in programs that included agriculture or environment-focused interventions. In several reports, including those concerning the fragile states of Afghanistan, Haiti, West Bank and Gaza, while projects were in conformity with the requirements of the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act at the design phase, environmental issues were not strongly addressed during implementation and, in the case of Haiti, environmental guidelines were reportedly not followed in some major electrical power and road construction projects, such as the Les Cayes-Jérémie Road project. On the other hand, the reports on Senegal, Ethiopia, Ghana and Indonesia country programs noted good integration of environmental considerations with results achieved in effective natural resources management, and the evaluation of the Bangladesh Program indicated that environmental requirements were met in all infrastructure-related initiatives.

Governance

Evidence of the effectiveness of governance integration in Gs&Cs programming was strongest in country program evaluations; development effectiveness reviews and foreign affairs evaluation reports made little explicit reference to governance issues. Overall, 46% of evaluation reports received a strong rating for governance and 50% were acceptable. The overall strong ratings in this area were likely due to the fact that governance was often identified as both a program priority sector and a cross-cutting theme and was evaluated accordingly.

Ten of the 18 country program evaluations reviewed Footnote 20 reported significant contributions to strengthening governance at national and sub-national levels and across various program sectors. The Mali and Indonesia country programs were particularly lauded for their effective role in strengthening governance at the local level.

Development effectiveness reviews had little information on how multilateral organizations are addressing governance. Only the UNDP review provided an assessment of the organization’s performance in this area. The report explained that UNDP achieved effective results in promoting democratic governance in recipient countries by promoting increased transparency, strengthening parliamentary systems, improving judicial and policing systems and enhancing peace-building.

Among the 11 evaluation reports on foreign affairs programming, the evaluation of the Canada Fund for Local Initiatives (CFLI) reported that the CFLI was effective in promoting democracy and human rights and that approximately 40% of CFLI funding was dedicated to initiatives supporting democratic transition and advancing democracy. The evaluation of the Americas Strategy noted important progress in the area of democratic governance in the Americas which received one-third of GAC’s democratic governance funding at the time of the evaluation (2011). The evaluation outlined several specific results achieved, including in the areas of conflict prevention and peace building efforts (Colombia) and in favour of civil society, open media outlets, and research networks focused on democracy.

3.6.4 Contributing Factors

This review identified that the following success factors in integrating cross-cutting themes:

- Global Affairs’ demonstrated leadership and promotion of cross-cutting considerations, particularly of gender equality in policy dialogue, consultations and advocacy (8/29 reports). This factor was noted mainly in country program evaluations: Mali, Senegal, Indonesia, the Caribbean, Bolivia and Peru.

- Advancing efforts for consistent and systematic integration of cross-cutting themes throughout the project cycle, including incorporating and measuring specific objectives and targets related to these themes (8/29 reports).

3.6.4 Limiting Factors

The review pointed to the following factors limiting the integration of cross-cutting themes: