Evaluation of the Stabilization and Reconstruction Task Force (START) and Global Peace and Security Fund (GPSF)

Final Report

Department of Global Affairs Canada

Office of the Inspector General

Evaluation Division

September 2016

Table of Contents

- Acronyms

- Acknowledgements

- Executive summary

- 1.0 Introduction

- 2.0 Evaluation scope & objectives

- 3.0 Key considerations

- 4.0 Evaluation approach & methodology

- 5.0 Limitations to methodology

- 6.0 Evaluation findings: relevance

- 7.0 Evaluation findings: Performance

- 8.0 Conclusions

- 9.0 Recommendations

- 10.0 Management response and action plan

Acronyms

- ADM

- Assistant Deputy Minister

- ACCBP

- Anti-Crime Capacity Building Program

- AICMA

- Comprehensive Action Against Anti-Personnel Mines

- AS

- Administrative Services

- CAD

- Canadian Dollar

- CAR

- Central African Republic

- CBSA

- Canadian Border Services Agency

- CCC

- Canadian Commercial Corporation

- CEFM

- Child, early and forced marriage

- CIC

- Centre on International Cooperation

- CIDA

- Canadian International Development Agency

- CF

- Canadian Forces

- CFLI

- Canada Fund for Local Initiatives

- C-NAP

- Canada’s National Action Plan on Women, Peace & Security

- CPA

- Canadian Police Arrangement

- CSC

- Correctional Services Canada

- CTCBP

- Counter Terrorism Capacity Building Program

- DART

- Disaster Assistance response Team

- DDR

- Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration

- DEC

- Departmental Evaluation Committee

- DFAIT

- Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade

- DG

- Director General

- DND

- Department of National Defence

- DoJ

- Department of Justice

- DPAT

- Deputy Project Accountability Team

- DRC

- Democratic Republic of Congo

- EAC

- Evaluation Advisory Committee

- EC

- Economic/social sciences

- ECOSOC

- UN Economic and Social Committee

- ERW

- Explosive Remnants of War

- EUC

- Eastern Europe and Eurasia Relations

- FOF

- Forum of Federations

- FS

- Foreign Service

- FTE

- Full Time Equivalent

- FY

- Fiscal Year

- GAC

- Global Affairs Canada

- GBP

- Glyn Berry Program

- GC

- Government of Canada

- GDP

- Gross Domestic Product

- GMAP

- Global Markets Action Plan

- GPOP

- Global Peace and Operations Program

- GPP

- Global Partnership Program

- GPSP

- Global Peace and Security Program

- GSRP

- Global Security Reporting Program

- HQ

- Headquarters

- HSP

- Human Security Program

- IAE

- International Assistance Envelope

- JRR

- Justice Rapid response

- ICC

- International Criminal Court

- ICITAP

- International Criminal Investigative Training Program

- ICM

- Independent Commission on Multilateralism

- ICTR

- International Criminal Tribunals for Rwanda

- ICTY

- International Criminal Tribunals for Former Yugoslavia

- ICTR

- International Criminal Tribunals for Rwanda

- IFM

- ADM International Security

- IICI

- Institute for International Criminal Investigations

- IOL

- Democracy Division

- INGO

- International non-governmental organization

- INL

- Bureau of International narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs

- IPP

- International Police Peacekeeping and Peace Operations

- IRC

- Deployment and Coordination Division

- IRD

- Stabilization and Reconstruction Task Force Bureau

- IRG

- Stabilization and Reconstruction Programs Division

- IRH

- Humanitarian Affairs and Disaster Response Division

- IRP

- Peace Operations and Fragile States Policy Division

- JRR

- Justice Rapid Response

- LES

- Locally Engaged Staff

- MAPP

- Mission to Support the Peace Process

- MHD

- International Humanitarian Assistance Division

- MHI

- International Humanitarian Assistance Operations Division

- MINUSMA

- UN Stabilization Mission in Mali

- MoD

- Ministry of Defence

- MOU

- Memorandum of Understanding

- MRM

- UN Monitoring and Reporting Mechanism

- NATO

- North Atlantic Treaty Organization

- NGO

- Non-governmental organization

- NRC

- Norwegian Refugee Council

- OAS

- Organization of American States

- ODA

- Official Development Assistance

- OECD

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development

- OECD-DAC

- OECD-Development Assistance Committee

- OGD

- Other government department

- ORF

- Office of Religious Freedom

- OSCE

- Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe

- PAT

- Project Accountability Team

- PCD

- International Assistance Envelope Management

- PCO

- Privy Council Office

- PHAC

- Public Health Agency of Canada

- PIA

- Project Initiation Authorization

- PIC

- Project Information Coordinator

- PM

- Programme Administration

- PMS

- Performance Measurement Strategy

- POL

- Foreign Policy Planning Division

- PS

- Public Safety Canada

- PSU

- Project Support Units

- PT

- GPSF Project Review Team

- RBM

- Results-based Management

- RCMP

- Royal Canadian Mounted Police

- RPP

- Report on Plans and Priorities

- SAB

- START Advisory Board

- SEA

- South East Asia

- SCSL

- Special Court for Sierra Leone

- SGBV

- Sexual and gender-based violence

- SME

- Subject Matter Experts

- SMM

- Special Monitoring Mission

- SOP

- Standard Operating Procedure

- SSPMT

- Security and Stability Project Management Tool

- SSR

- Security system reform

- START

- Stabilization and Reconstruction Task Force

- STL

- Special Tribunal for Lebanon

- TB

- Treasury Board

- UNSCR

- UN Security Council Resolution

- USDP

- Union Solidarity and Development Party

- UXO

- Unexploded Ordinance

- Ts&Cs

- Terms and Conditions

- TBS

- Treasury Board Secretariat

- WPS

- Women, Peace and Security

- ZID

- Office of the Inspector General

- ZIE

- Evaluation Division

Acknowledgements

The evaluation team would like to express its appreciation to the many individuals and organizations who agreed to contribute to this evaluation by offering honest feedback on the relevance and performance of START and GPSF, as well as by sharing their experience and good practices with similar programs. Special gratitude is extended to the Heads of Canadian Diplomatic Missions and mission staff in countries where START has implemented major projects for agreeing to be interviewed and for their support in organizing meetings for the evaluators with program beneficiaries and like-minded partners. The evaluation team would also like to thank START program managers and project officers for their support with relevant information and documents, as well as for their patience during the evaluation process. We would also like to acknowledge the contribution of Catherine Gander to the development of the cases studies on Colombia and SGBV. Lastly, the team would like to extend its appreciation to the members of the Evaluation Advisory Committee (EAC) for their participation and feedback during this evaluation.

Executive summary

In 2005, recognizing the need for an appropriate mechanism to fill the programming gap between immediate humanitarian assistance and longer-term development and security sector assistance, the Government of Canada (GC) created the Stabilization and Reconstruction Task Force (START) with a mandate to advance Canada’s foreign policy priorities of addressing international security challenges and promoting the Canadian values of freedom, democracy, human rights, and rule of law in fragile and conflict-affected states. Subsequently, in April 2005, the Global Peace and Security Fund (GPSF) was launched with a notional budget of $100 million per year and a five-year mandate. Managed by START, GPSF was created to fill a funding and operational gap within what was at the time the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade (DFAIT), now Global Affairs Canada (GAC) for programming that ensures a rapid and efficient whole-of government response to crisis situations, both natural and human inflicted.

The purpose of this summative evaluation is to provide the Department’s senior management with a neutral and evidence-based assessment of the relevance and performance (value for money) of START and GPSF. The evaluation covered START and GPSF initiatives and programming activities implemented between April 2010 and September 2015. A mixed method approach was used to collect quantitative and qualitative data from a variety of sources. In-person and telephone interviews were conducted with over 190 key international and domestic stakeholders. ZIE evaluators conducted field visits to nine countries in South East Asia, Europe, the Middle East and North America which allowed for direct observation of achieved outcomes and interviews with program staff and beneficiaries.

An extensive document review was also used to complement the interviews and field visits. A comprehensive desk review of a sample of 84 projects, selected from the 390 START/GPSF projects implemented over the evaluation reference period, allowed for an in-depth analysis of the degree to which projects have achieved their expected outcomes and the way these have been tracked and reported. A comparative analysis of like-minded countries’ stabilization programming was also researched and their best practices were used to complement analysis and provide benchmarks for comparing START and GPSF achievements. Finally, thematic case studies on mine action and sexual and gender based violence (SGBV) programming and country case studies on programming in Colombia, Jordan and Ukraine provided additional insight for the evaluation.

Key Findings

1.0 Relevance

Crises, both natural and human inflicted, contribute to regional and international instability that threaten Canadians and Canadian interest both directly and indirectly. Global security and conflict trends suggest that instability will continue to pose a threat in the near future as exemplified by a number of new and ongoing crises in the Middle East, Africa, Asia and the Americas, and the increase in the reach and scope of radical Islamist groups. With many of these threats originating in fragile and conflict-affected states, Canada, along with its allies, has a compelling reason to combat these threats at the source.

The international community has united in recent years in the search for concerted and coordinated ways to address the drivers of instability and conflict. Recognizing the fact that addressing the challenges of fragile and conflict-affected states requires a more holistic approach, a number of Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries, such as Denmark, France, Germany, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom (U.K.) and the United States (U.S.) have either established or further strengthened their stabilization capacities and related organizational and programming structures to address the specific challenges and threats arising from such states.

Prior to the creation of START, policy and programming in fragile and conflict-affected states were fragmented between different GC departments and agencies. This deficit called for the development of a standing capacity to monitor crisis situations, plan for and rapidly deliver integrated policy and programming responses, drawing upon the collective and coordinated contributions of government departments. With the increase in the number of fragile states around the world in conflict or at risk of conflict, the rationale for START and GPSF has never been more compelling. In addition, GAC is uniquely positioned within the GC to provide whole of government operational support and coordination to Canadian interventions in response to international crises making it the logical home for START and GPSF.

START and GPSF have been highly responsive to both the geographic and thematic priorities of the government of the day; however, aligning programming with these priorities may have occasionally led START and GPSF to deviate from their core areas of focus and competence. For instance, START implemented projects in some countries that have not been in conflict or at risk of conflict, nor even fragile by international standards (e.g., Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Moldova, Paraguay, etc.), while at the same time reducing programming in other countries and regions (i.e. East and West Africa) seriously affected by instability and conflict. During the same period, START also programmed in domains such as counter-terrorism, anti-crime, humanitarian mine action, social/welfare services, reproductive health care, medical services, and human rights, which, though tangentially related to its mandate, fall within the purview of other departmental programs.

2.0 Performance

Direct observations and evidence collected during the field visits indicated that most projects have achieved their immediate and intermediate outcomes, however, there was little or no reporting on how these project results have contributed or are contributing to the overall program-level outcomes. The evaluation assessed and summarized aggregated results under each of the four “Results Stories”, defined by the intermediate outcomes in the START logic model.

Projects aimed at achieving Intermediate Outcome #1: Strengthened Institutions and Civil Society in Affected States accounted for the largest share of GPSF disbursements over the evaluation period. The evaluation found that START projects contributed to increased capacity of state institutions and civil society organizations to address instability, manage conflict, and deliver services that helped restore stability and security in a number of fragile and conflict-affected states. In terms of performance under Intermediate Outcome #2: Strengthened Government of Canada Crisis Response, the evaluation found that START has developed strategic and operations tools and procedures to support timely responses to natural disasters and complex emergencies. However, the evaluation noted that the GC’s response to emerging and protracted crises has been uneven over the past five years which has impacted the ability of START to deliver upon its full mandate. The evaluation found that START’s support to international institutions continues to constitute the largest share of program disbursements but that the overall level of support declined over the past five years which impacted the program’s performance under Intermediate Outcome #3: Strengthened International Responses to Specific Crisis Situations.

START’s fourth intermediate outcome, Strengthened International Frameworks for Addressing Crisis Situations, focusses on START’s contribution to the broader GC policy dialogue and advocacy to strengthen international frameworks. With the exception of its work on Women, Peace, and Security, START has, over the evaluation reference period, achieved little by way of contributing to the development of new frameworks to address crises. Interlocutors and interviewees attributed this to a number of factors, including but not limited to the uncertainties related to the renewal of START’s funding authorities, the Project Initiation Authorization (PIA) process, according to which every single project proposal had to be approved by the Minister of Foreign Affairs, as well as the directed programming instituted by the Office of the Minister. The governance structure of START has evolved since the 2009 official re-organization of the Program. The evaluation found that the introduction of the PIA process in 2011 and the emergence of parallel centres of policy expertise have caused some ambiguities around roles, responsibilities and accountabilities with regard to policy and programming.

In addition, strategic planning within START has been affected by the PIA process and uncertainties related to renewals of GPSF funding authorities. The lack of an overall, multi–year strategy for a whole-of-government approach to crisis response and stabilization initiatives in priority countries has reportedly hindered START’s ability to monitor and measure progress and report on the achievement of results against clear goals and expected outcomes. In particular, the absence of country and thematic/sector strategies in the context of stabilization has led to dispersed and uneven programming, informed by opportunities rather than strategic planning.

START has instituted a robust project review process with challenge functions performed by the Project Accountability Team (PAT) and the Deputy Project Accountability Team (DPAT). The institution of the PIA process, however, affected the ability of PAT and DPAT to perform genuine challenge functions and allowed for projects of marginal relevance to START’s mandate to be approved.

The evaluation found that operational coordination in response to natural disasters, such as the Haiti earthquake, Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines, and the Nepal earthquake, has been robust and effective, backed by strong standard operating procedures (SOPs), and the routine conduct of post-response assessments and evaluations of each major intervention. However, the level of operational and whole-of-government coordination and planning for GPSF programming in fragile and conflict affected states, except for Ukraine and Syria, was found to be not as strong as that for natural disasters.

START demonstrated some improved coordination with GAC’s security programs over the past two years, but coordination and leveraging of synergies with development programming in the field was found to be inconsistent. Coordination with international partners in stability and security projects has been stronger where START made significant investments and where START had a field presence. Although, this does not compensate for the prolonged interruptions in engagement and funding of projects in Haiti, Colombia and South Sudan, as well as the withdrawal of START’s field representatives, which have led to reduced participation of Canada in donor coordination fora, and have been viewed by international partners and implementing organizations as negatively impacting Canada’s image as a reliable partner and contributor to the peace process in these countries.

START’s performance in leveraging the expertise of other government departments (OGDs) to contribute to stabilization efforts diminished over the evaluation reference period. For instance, START contributions to the Canadian Police Arrangement (CPA) in partnership with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) and Public Safety (PS) declined, as did START’s civilian deployments. START and GPSF have demonstrated some success in leveraging the resources of other partner governments, such as the U.S. and U.K., to deliver its programming and enhance program/project efficiency and effectiveness.

START’s capacity to disburse funds rapidly, compared to other funding instruments, is one of its strengths; however, the PIA process impacted adversely the efficiency of START’s programming.. The three short-term renewals of GPSF’s funding authorities over the evaluation reference period also led to reduced windows for programming and project approval delays led to necessitated changes to the originally proposed activities by partners and implementers.

START has developed a risk management framework (currently under review); however, adherence to this framework was found to be inconsistent. The reduced ability of PAT and DPAT to perform a challenge function has been attenuated by the directed programming and the limited technical capacity within START to identify risks (financial, fiduciary and implementation risks). The lack of START officer field presence also reduced the ability of the Program to develop timely risk management strategies in response to changing security levels. In 2015, IRP developed a special “Risk Map” and “Risk Monitor” tool which provides a general overview of emerging trends in fragile states but, except for a “Burma Conflict and Fragility Assessment” paper, no other evidence was found of detailed country-level conflict analysis. Monitoring at the project and program level was also found to be incommensurate with the level of project funding and related programming risk.

START has instituted a good project management tool that includes both project and financial information; however, there has been insufficient oversight of the quality of information entered. The evaluation found that the quality of the data entered varied depending on the level of training and expertise of the project officers. The frequent turnover of START staff with different project managers starting and closing a project was also referenced as a contributing factor to the inconsistent reporting.

START has developed a performance measurement framework and logic model identifying its expected outcomes; however the lack of alignment with the Program’s Security and Stability Project Management Tool (SSMPT) has reduced their use for planning and reporting purposes. The fact that the SSMPT does not allow for input of outcomes as defined in START’s logic model makes the demonstration of results at the program level particularly difficult. Additionally, in the absence of relevant outcome-level data, program managers cannot easily aggregate project results to check if the program is on course for achieving its intended outcomes.

START had developed a human resource strategy and training programs to support continuous learning; however, their irregular implementation and uncertainties relating to funding authorities have created staff and corporate memory retention challenges. For instance, when training did occur over the evaluation period, it was reported to be largely confined to the Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) and more process rather than substance-oriented. The high turnover rates also resulted in frequent changes of the project officers/contact points for international partners and for other GAC divisions and missions, leading to loss of corporate memory, continuity and knowledge-sharing.

START’s spending has been uneven over the past five years with significantly lower spending in 2012 and 2013, resulting in inefficiencies, such as higher administrative costs, reduced opportunities for program managers to maintain relationships with other donors and increased risks for the sustainability of project results.

The experience of like-minded countries and major international organization has unequivocally demonstrated that preventing crisis situations is cheaper than dealing with conflict, and provides much higher value-for-money spent on security programs, especially when they are helping to prevent costly military interventions. The evaluation found that during the past five years, START had increasingly focussed its programming on the symptoms of conflict rather than on the root causes of instability.

Recommendations

Recommendation #1: While the assumptions that have informed the creation of START and GPSF remain largely valid, the evolving nature of security threats and state conflict require that START reassess its strategic objectives, policy and programming priorities.

Recommendation #2: START should re-introduce longer-term strategic planning for major programming themes and promote sustainable results, while retaining its ability to respond quickly to emerging and evolving needs.

Recommendation #3: START should continue improving its coordination with other GAC policy and programming streams, particularly with development, both at headquarters (HQ) and in the field.

Recommendation #4: START should strengthen its performance measurement systems and practices at the overall program, country, thematic and project levels.

Recommendation #5: START should increase gender-focused planning and programming, and improve the integration of gender considerations in all projects across thematic areas and priority countries.

1.0 Introduction

The summative evaluation of the Stabilization and Reconstruction Task Force (START) and the Global Peace and Security Fund (GPSF) was undertaken as part of the Five-Year Evaluation Plan of the Evaluation Division (ZIE) in the Office of the Inspector General (ZID) and in response to a Treasury Board (TB) requirement for the potential renewal of GPSF beyond March 31, 2016.

This evaluation started in June 2015 and covers a reference period of five years from April 2010 to October 2015, which represents the time elapsed since the last START/GPSF summative evaluation. The target audience for this evaluation is Global Affairs Canada (GAC) senior management, program directors and project officers; central agencies; and the Canadian public.

1.1 Background and Context

International peace and security are increasingly threatened by the growing number of crises triggered by armed conflicts, terrorist activities, state fragility, and natural disasters. Addressing violence and the consequences of humanitarian crises and complex emergencies represents a major challenge for the international community, which has become increasingly cognizant of the fact that without timely and coherent support, fragile and conflict-affected states will continue to present a threat to global security.

The Government of Canada’s (GC) response to the need to mitigate crises, prevent conflicts and state failures, and contain potential spillovers of violence materialized in a set of discrete programs for countries of concern. The Human Security Program (HSP), established in 2000, was one of the first programs with a five-year mandate (2000 – 2005) and an annual budget of $10 million designed to support diplomatic leadership, policy advocacy, country-specific initiatives and domestic and multilateral capacity building initiatives, predominantly in Africa.

In 2005, recognizing the need for an appropriate mechanism to fill the funding and operational gap between immediate humanitarian assistance and longer-term development and security sector assistance the GC created START. Its mandate was to advance Canada’s foreign policy priorities of addressing international security challenges and promoting the Canadian values of freedom, democracy, human rights, and rule of law abroad. GPSF was launched in April 2005, with a notional budget of $100 million per year and a five-year mandate. Managed by START, GPSF was created to ensure a rapid and efficient whole-of-government response to crises that are natural or human-inflicted disasters.

Evolution of GPSF Funding Authorities

In September 2006, the TB approved spending authorities for programming under GPSF in Sudan, Haiti, and Afghanistan, along with funding for the International Police Peacekeeping and Peace Operations Program (IPP) through FY 2009/10. Policy and spending authorities after March 31, 2007 for other GPSF programs, such as the Global Peace and Operations Program (GPOP), HSP (renamed the Glyn Berry Program), and the Fragile States Initiative, required Cabinet and separate TB approvals. After these authorities were granted in June 2007 and funding in the amount of $224.4 million was approved for the three programs, START became GAC’s and Canada’s integrated platform for policy, programming and quick operational response to conflicts, crises and natural disasters. In 2008, the policy and funding authorities for START and GPSF were extended for five years until 2012/13 at CAD $164.7 million per year. At the same time, GPSF was given multi-year authority for project-based programming and endorsement to engage in fragile states other than Afghanistan, Sudan and Haiti. GAC’s continued management of the International Assistance Envelope (IAE) Crisis Pool through the START Secretariat was also endorsed that year.

In April 2013, a Program extension for up to one year was approved, followed by another six-month extension until September 30, 2014. On September 29, 2014, the TB approved an 18-month extension of GPSF policy and funding authorities until March 31, 2016.

1.2 Program Mandate, Objectives and Activities

The underpinning rationale for START was the recognition that in order to effectively deal with the complexities of fragile states and international crises, the GC needed a whole-of-government approach combining the policy, programming and coordination capacities of the Foreign Service, the development agencies, as well as the justice, policing, correctional and military services. START enabled the creation of such synergies through the use of expertise from all relevant departments and agencies. With a mandate focused on policy development, coherence and advocacy in the areas of conflict prevention, crisis response, civilian protection and stabilization in fragile states, START also became a platform for operational support and coordination of international crises – both natural and human-inflicted. Since its operationalization in 2006, GPSF has been used to deliver high-impact programming in Afghanistan, Haiti, Sudan, Lebanon, Colombia, Uganda, the West Bank and Gaza, with Ukraine and Jordan gaining special attention over the evaluation reference period. A particular emphasis was also recently placed on safeguarding the human rights and well-being of women and children in situations of conflict and state fragility, as well on the prevention of sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV).

The main objectives of START have undergone various articulations since its establishment, conveying slightly different perspectives of the focus of the program but still capturing the key elements of its mandate. While this was partly due to the changing security environment, global trends and government priorities, it was also an attestation of START’s flexibility and ability to adapt its programming to evolving needs. For example, during the first five years, programming was mostly focussed on Afghanistan, Haiti and Sudan, subsequently moving to countries such as Colombia, and more recently, to Jordan, the West Bank and Ukraine.

Due to the cross-cutting thematic work in various priority areas, over the past five years START/GPSF has attempted to undertake a more holistic approach to regional and country programming under specific thematic priorities to better respond to newly emerging security and stabilization needs of fragile and conflict-affected states. The main GPSF thematic areas and expected results for the past five years are reflected in the START Logic Model and specified, under the following four “Result Stories”:

- Strengthening institutions and civil society in affected states

- Strengthening Government of Canada’s responses to crisis situations

- Strengthening international responses to specific crisis situations

- International frameworks in use for addressing crisis situations

START collaborates with a variety of stakeholders both within GAC and externally, many of whom contribute to/or benefit from the programming activities. Policy, programming and operations are often delivered in cooperation with partners such as allied governments and intermediaries external to GC (recipients of GPSF resources and/or implementing entities), including Canadian and international non-governmental organizations (NGOs), civil society and multilateral organizations. For example, START manages GPSF and the deployment of GC civilian experts, works with the Department of National Defence (DND) to deploy Canadian Forces (CF) personnel into multilateral peace operations, and coordinates the Canadian Police Arrangement (CPA) with Public Safety Canada (PS) and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) to deploy civilian police officers as part of international peace operations.

Target populations may vary depending on the conflict, crises or natural disaster in which START engages, with beneficiaries including a range of age groups, genders, and marginalized or vulnerable populations.

1.3 Governance

The governance structure of START is multi-layered and reflective of its complex role as the GC focal point for international stabilization work, and its related policy, programming and operational responsibilities.

The START bureau is managed by a Director General of the Stabilization and Reconstruction Task Force Bureau (IRD) who reports to the Assistant Deputy Minister (ADM) for International Security (IFM). To ensure policy coherence and to avoid duplication, various inter and intradepartmental committees (Deputy Minister (DM), ADM and Director General (DG) levels) are called upon as required to inform and guide emerging priority-setting exercises and implement Cabinet mandated priorities in the whole-of-government context, the main being the START Advisory Board (SAB) - an interdepartmental oversight body (DND, Privy Council Office (PCO), RCMP, Canadian Border Services Agency (CBSA), Correctional Services Canada (CSC) and Department of Justice (DoJ), etc.). At various stages throughout the project life cycle, challenge and review functions are performed by internal review committees (the Project Accountability Team (PAT) and the Deputy Project Accountability Team (DPAT)).

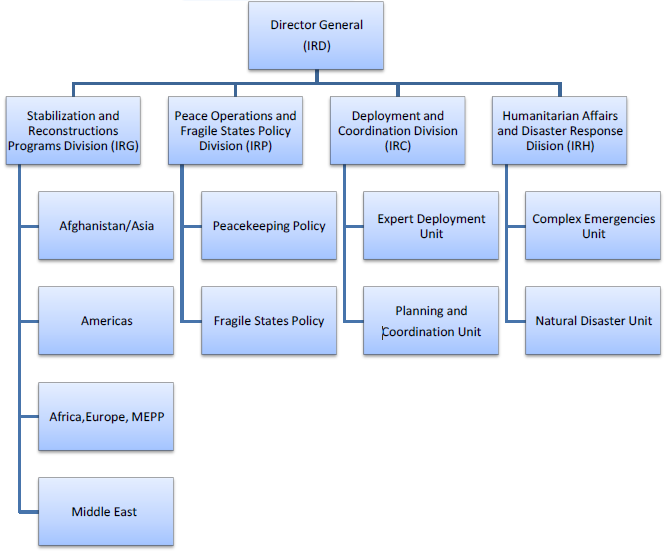

Within IRD, there are currently four functional divisions, each fulfilling a specific function:

- Stabilization and Reconstruction Programs Division (IRG): Conducts programming activities along the main geographic regions and thematic priorities.

- Peace Operations and Fragile States Policy Division (IRP): Develops and coordinates policy around fragile states, conflict management, international peacekeeping and peace building initiatives.

- Deployment and Coordination Division (IRC): Provides advice, guidance and direction for the entire IRD bureau with regard to business processes, risk and performance management; conducts an independent review of all projects to ensure compliance with requirements and guidelines, coordinates and manages whole-of-government expert civilian deployments including the CPA.

- Humanitarian Affairs and Disaster Response Division (IRH): Develops, coordinates and implements Canada’s policy on international humanitarian affairs, and Canada’s responses to international humanitarian crises caused by both natural disasters and armed conflict.Footnote 1

Text version

1.4 Program Resources

The Stabilization and Reconstruction Task Force Bureau (IRD) employs 68 direct Full-Time Equivalent (FTEs). Position classifications include Administrative Services (AS), Programme Administrative (PM), Foreign Service (FS) and Economic/Social Science (EC).

START/GPSF funds are earmarked in the fiscal framework for Peace and Security initiatives within the International Assistance Envelope (IAE) with most of the programming falling within the scope of Official Development Assistance (ODA).

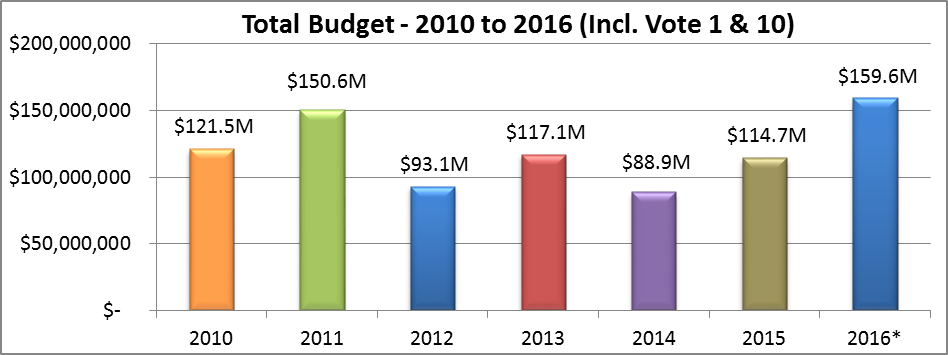

In the period April 1, 2010 – March 31, 2015, START’s annual budget allocations varied considerably (between $89M and $150M) due to the number of different TB spending authorities granted over the five-year reference period.

The graph below represents the total START/GPSF budget allocations (including Vote 1 and 10) by fiscal year (FY) from 2010 to 2016.Footnote 2

Text version

- The graph represents the total START/GPSF budget allocations (including Vote 1 and 10) by fiscal year (FY) from 2010 to 2016.

- 2010: $121.5 million

- 2011: $150.6 million

- 2012: $93.1 million

- 2013: $117.1 million

- 2014: $88.9 million

- 2015: $114.7 million

- 2016: $159.6 million

* Final information for FY2015-2016 was not available at the time of report writing.

Annually, between $12.5 and $14 million from Vote 1 funding is provided to RCMP for the CPA. This program was evaluated separately, as a horizontal evaluation, jointly with RCMP and PS, therefore it is not part of this evaluation.

More detailed description and analysis of the disbursement trends over the past five years are presented in the Efficiency and Effectiveness section of this report.

2.0 Evaluation scope & objectives

2.1 Objectives

The purpose of this summative evaluation was to provide the Department’s senior management with a neutral and evidence-based assessment of the relevance and performance (value for money) of START and GPSF.

The specific objectives of this evaluation were as follows:

- To determine the relevance of START and GPSF by assessing the extent to which they address a demonstrable need, continue to be aligned with the priorities of the GC and represent an appropriate role for the GC and GAC to fulfill.

- To evaluate the performance of START and GPSF in achieving their expected outcomes efficiently and economically.

- To reflect on the lessons learned from the management of individual GPSF projects and best practices that could inform future initiatives and the program.

2.2 Scope

The evaluation was built upon the findings and recommendations of the 2009 GPSF Summative Evaluation and is specifically focussed on achieved outcomes from START and GPSF initiatives and programming activities implemented between April 2010 and September 2015.

In addition to the analysis of specific programming activities and projects implemented by IRG, the evaluation also covers the overall functions and corporate management of the START Bureau, including the policy initiatives executed by IRP, the crises response activities of IRH, and the civilian deployments executed by IRC.

In the context of an amalgamated department, the evaluation also assessed the extent to which opportunities for synergies and enhanced cooperation between GPSF and other GAC development and humanitarian programs have been leveraged.

Based on the evaluation findings and conclusions, recommendations are made with regard to identified areas for improvement.

3.0 Key considerations

Over the past five years, START and GPSF have operated under a number of authorities and temporary extensions, resulting in planning and programming challenges and interruptions in the implementation of their respective mandates. For example, until March 31, 2013, GPSF was guided by the 2008 TB submission and related Terms and Conditions (Ts&Cs). From April 2013 to September 2014, START/GPSF operated under two short-term funding extensions, which prevented program staff from making long-term planning commitments and in some cases, impacted the thematic scope and duration of implemented projects. The 2014 TB Submission ensured that program authorities would extend until March 31, 2016.

Another consideration for the evaluation was the fact that programming under GPSF is mainly delivered in fragile and conflict-affected states, with volatile security environments, making the identification of evolving needs and designing respective rapid response options to these needs more challenging. Direct monitoring of project implementation in some countries has also been difficult or impossible for safety and security reasons.

4.0 Evaluation approach & methodology

This evaluation follows the 2009 Treasury Board Policy on Evaluation and is conducted along the five core evaluation issues and questions which are aligned to data sources and analytical approaches defined in the evaluation matrix.

A mixed methodological approach and a variety of techniques were employed for the collection and analysis of qualitative and quantitative data. In-person and telephone interviews were conducted with over 190 key international and domestic stakeholders. ZIE evaluators did field visits to nine countries in South East Asia, Europe, the Middle East and the US which allowed for in-person interviews with program implementers and beneficiaries, as well as for direct observations of achieved outcomes in some cases. An extensive document review was used to complement the interviews with evidence on the way activities and projects are planned, governed, implemented and documented, and the extent to which results and outcomes are being tracked and reported. A more detailed desk review of a sample of 84 projects, selected from the 390 (n=390) START/GPSF projects implemented over the evaluation reference period, allowed for an in-depth analysis of the degree to which GPSF projects have achieved their expected outcomes, and the way these have been monitored, tracked, and reported.

The experience of like-minded countries in stabilization programming was researched and their best-practices used to complement the analysis and provide some benchmarks for comparing START’s and GPSF’s achievements. Thematic case studies on mine action and SGBV programming under START /GPSF and country case studies on Jordan, Ukraine and Colombia provided additional insight for the evaluation.

5.0 Limitations to methodology

A major challenge for the evaluation was the broad scope of GPSF programming. GPSF covers multiple themes and sectors, an array of programming activities, a wide geographic scope and works with multiple implementing partners which culminated in around 400 projects implemented during the evaluation reference period. The large breadth and scope of GPSF programming during the reference period and the short timelines to collect evidence from primary data sources constrained the ability of the evaluators to observe first-hand results from some major projects (e.g. no field visits were conducted to Haiti, Afghanistan, Iraq and countries in Africa). To mitigate this limitation, the evaluation team conducted a desk review of a representative sample of projects that included GPSF programming activities across the major themes, sectors, countries and regions. In addition, field visits to four different regions and eleven countries provided direct observations of project results and good coverage of diverse areas of operation and intervention.Footnote 3

Another challenge was the evolution of START’s structure as a bureau and the roles and responsibilities of its divisions over the reference period. Not all structural changes and the rationale for these changes were recorded, which made it difficult to assess their actual impact on the efficiency and effectiveness of START/GPSF activities and projects. In order to mitigate against this challenge, the evaluation team conducted a review of best practices in security and stabilization programming, and met with representatives of like-minded partners to explore their policy approaches to stabilization, peace-building and democracy and the relevant institutional structures created to support policy and programming in these areas.

6.0 Evaluation findings: Relevance

6.1 Relevance Issue #1: Continued Need for the Program

Finding 1: Crises, both natural and human-inflicted, continue to contribute to regional and international instability which threatens directly and indirectly Canadians and Canadian interests.

The accelerated pace of globalization over the past several decades, made possible in large measure by the significant decline in the costs of transportation and dramatic advances in information technology, has increasingly eroded traditional state borders and created growing interdependence among states. The progressive breakdown of barriers between nations and peoples has, in turn, increased opportunities for the exchange of ideas, economic development, and travel to previously inaccessible places. In addition, advancements in technology have increased the access to information and empowered civil society on a global scale. Despite its multiple benefits, globalization has also proven to be a powerful destabilizing force in the world.

While not a cause of conflict in itself, globalization can intensify the social and economic drivers of conflict and greatly increase their complexity. More importantly, the growing interdependence of nations through global and financial trade markets and the increase in the movement of peoples means that instability and crises occurring in one state may have spillover effects in neighbouring countries leading to regional and international instability. The increasing use of social media can further accelerate the speed and reach of the diffusion effect, as most recently observed during the Arab Spring in 2011. Such instability, and the violence associated with it, is further compounded by other significant global trends including population growth, climate change, and global income inequality which have stressed critical infrastructure and rendered populations vulnerable to natural disasters.Footnote 4

Crises, both natural and human-inflicted, contribute to regional and international instability that threaten Canadians and Canadian interest both directly and indirectly. For instance, conflicts disrupt economic activities and adversely affect trade, especially for trade dependent countries such as Canada, by limiting access to foreign markets and destroying valuable resources. In terms of financial cost, the impact of violent conflict on the global economy is substantial: in 2015 the Global Peace IndexFootnote 5 estimated that U.S. $14.3 trillion was lost to the global economy, or 13.4 per cent of world gross domestic product (GDP), due to political instability and conflict. Conflict can also lead to the creation of failed states which provide a breeding ground for violent extremism and a safe haven for transnational terrorist groups.

Global security and conflict trends suggest that instability will continue to pose a threat in the near future as exemplified by a number of new and ongoing crises in the Middle East, Africa, Asia and the Americas, and the increase in the reach and scope of radical Islamist groups. With many of these threats originating in fragile and conflict-affected states, Canada, along with its allies, has a compelling reason to combat these threats at the source.

Finding 2: Responding to threats posed by fragile and conflict- affected states has emerged as a discrete domain of foreign policy with a set of established policy and programming structures, related principles, approaches and best practices.

There is growing international consensus that development, security and stability are deeply interconnected and mutually reinforcing concepts and that development goals and priorities cannot be achieved in the absence of a secure, legitimate and peaceful environment. The international community has united in recent years in the search for concerted and coordinated efforts to address the drivers of instability and conflict.Footnote 6 United Nations (UN) organizations have repeatedly emphasized that both financial and human costs associated with conflict prevention are less than those required to contain full-blown conflicts.

Building on the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Fragile State Principles, which articulated best practices for fragile state engagement, the International Dialogue on Peacebuilding and State building declared in 2011 a New Deal for Engagement in Fragile States which set out five key peacebuilding and state building goals:

- Fostering inclusive politics

- Establishing security

- Increasing access to justice

- Generating employment and improving livelihoods

- Managing revenue and delivering services

Both the OECD Fragile State Principles and the New Deal emphasize the importance of building resilience in fragile and conflict-affected states and establishing benchmarks for effective programming.

There is also an observed relationship between conflict prevention and long-term development. Conflict prevention assists in creating a secure and stable environment for development efforts to flourish. Long-term development is essential for preserving and protecting gains made in preventing conflict relapse. The recently adopted 2030 Sustainable Development Goals explicitly acknowledge that sustained development cannot take place in the absence of peace and security. Recognizing that addressing the challenges of fragile and conflict-affected states requires a more holistic approach, a number of OECD countries such as Denmark, France, Germany, Netherlands, United Kingdom (U.K.) and the United States (U.S.) have either established or further strengthened their stabilization capacities and related organizational and programming structures to address the specific challenges and threats arising from such states.

For instance, the Bureau of Conflict and Stabilization Operations in the U.S.’ State Department has a similar mission to that of START, namely “… to advance national security by working with partners to break cycles of violent conflict, strengthen civilian security, and mitigate crises in priority countries by providing analysis, strategic planning, and on-the-ground operations.”Footnote 7 Likewise, the U.K. has a Stabilisation Unit that coordinates government action in fragile and conflict-affected states.Footnote 8 Some of these initiatives are discussed below in this evaluation report, either for comparison of international policies and approaches, or for identification of good practices and lessons learned.

While each of the above-mentioned stabilization offices is configured differently, they all share certain common characteristics. They consolidate policy leadership, including fragile state and conflict analysis and whole-of-government coordination; maintain sources of funding dedicated to support the work of these offices/organizational structures; have flexible funding authorities to support short-term, rapid responses to crises, as well as longer-term stabilization goals; and retain the capacity to mobilize civilian experts for deployments from both the public and private sectors to support stabilization work.

Finding 3: The assumptions informing the creation of START and GPSF remain valid. There is a clear and compelling rationale for the continued existence of an organization/program like START and the provision of funds through a mechanism like GPSF that ensures whole-of-government response to international crises, complex emergencies, peacekeeping and stabilization needs in fragile and conflict-affected states.

Prior to the creation of START, policy and programming in fragile and conflict-affected states were fragmented between different GC departments and agencies. Mechanisms in support of whole-of-government coordination in response to crisis (natural and human-inflicted) were formed on an ad hoc basis to address a particular event which did not allow for pre-crisis analysis or prevention. This deficit called for the development of a standing capacity to monitor crisis situations, plan for and rapidly deliver integrated policy and programming responses, drawing upon the collective and coordinated contributions of government departments. START was the GC’s answer to that institutional deficit.

GPSF, for its part, was created “to fill a funding gap” within the GC by providing dedicated resources to support timely activities for countries at risk of conflict or in conflict, but which were not within the mandate or responsibility of DND, Canada’s ODA Program, and/or OGDs with capacities relevant to fragile state programming. GPSF performs two key functions consistent with international best practices with respect to fragile and conflict-affected state engagement: first, GPSF provides the GC with a rapid disbursement funding instrument which did not exist prior to its creation and; second, GPSF provides the GC with a funding instrument to effect whole-of-government resource mobilization, enabling OGDs to contribute their unique knowledge and skills to conflict prevention, post-conflict stabilization and reconstruction efforts.

The assumptions informing the creation of START and GPSF, therefore, remain valid. Since their creation, START and GPSF have demonstrated their relevance to addressing the needs of states in crisis, as evidenced by START’s role in:

- Mobilizing the resources of OGDs and coordinating their efforts in response to natural disasters, e.g. the earthquakes in Haiti (2010), New Zealand (2011), and Nepal (2015), as well as the devastating aftermath of Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines (2014) and Typhoon Etau in Japan (2015), which precipitated the disaster at the Fukushima nuclear power plant;

- Supporting security system reform (SSR) in Afghanistan, Haiti, Colombia, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Rwanda, the West Bank and Gaza, Iraq and Ukraine;

- Supporting transitional justice and reconciliation in Colombia, Mali, Somalia, Cambodia and Lebanon;

- Supporting democratic governance institutions and civil society (including legislatures and political party systems, electoral processes, human rights and rule of law, independent media, etc.) in Burma, Moldova, Egypt, Afghanistan, Tunisia, Kenya, Ukraine; and

- Supporting mine action in Colombia, Sri Lanka, Vietnam, Libya, Jordan, South Sudan and Ukraine.

With the increase in the number of fragile states around the world in conflict or at risk of falling into conflict, the rationale for START and GPSF continues to be compelling.

6.2 Relevance Issue #2: Alignment with Government Priorities

Finding 4: START’s policies, programs and initiatives are consistent with and supportive of GC priorities and GAC strategic outcomes; however, responding to these overall priorities has sometimes led START to program in areas only tangentially related to its specific mandate.

Addressing the threats to Canadian interests, and those of Canada’s allies, posed by fragile and conflict-affected states has been a priority for the GC throughout the evaluation reference period. In the GAC 2014-2015 Report on Plans and Priorities (RPP), under foreign policy priority #4 - “Promote democracy and respect for human rights and contribute to effective international security and global governance” – it is stated that “freedom, democracy, human rights and the rule of law are central to Canadian foreign policy and national security, and Canada will continue to advance these values in key regions such as the Americas and in countries such as Afghanistan, Iran, Ukraine and Burma”.

START continues to align with the GC’s peace and security priorities and advances its foreign policy goal of reasserting Canada’s leadership in the world. This priority is articulated in both the December 4, 2015 Speech from the Throne and the Prime Minister’s 2015 mandate letter to the Minister of Foreign Affairs.

Advancing security continues to be a thematic priority of Canada’s International Assistance Envelope (IAE). As such, START and GPSF are mandated to support GAC’s policy and programming in the IAE’s “security and stability” and “advancing democracy” pillars, and to permit Canada to address global challenges that threaten security and prosperity, through effective action in crisis situations, including the promotion of democracy, human rights, the rule of law and religious freedom.

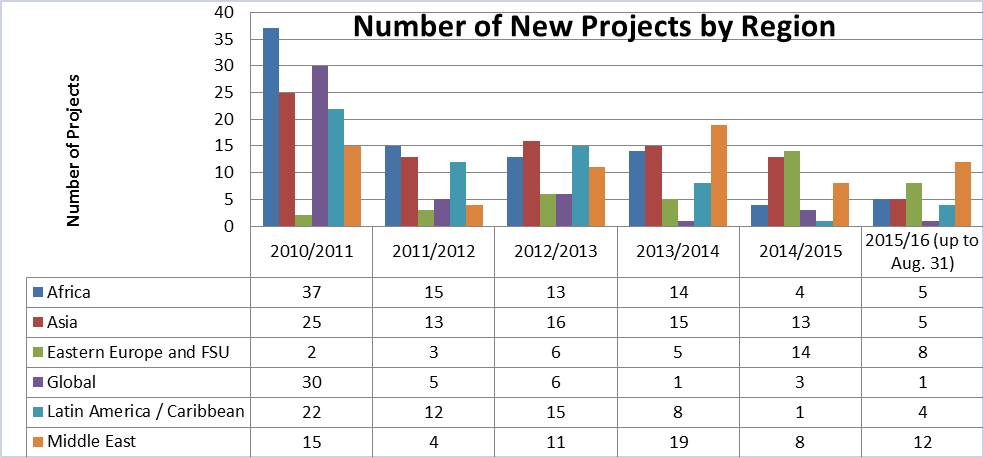

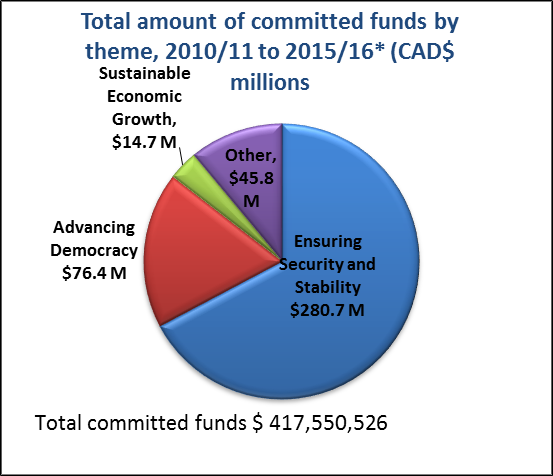

START and GPSF have been highly responsive to both the geographic and thematic priorities of the government, evidenced by the realignment of committed funds to emerging crises in Eastern Europe and the Middle East and North Africa.

Text version

- The graph represents the number of new START/GPSF project by geographic region between 2010/11 and 2015/16 (up to August 31st).

- Africa: 2010/11: 37, 2011/12: 15, 2012/13: 13, 2013/14: 14, 2014/15: 4, 2015/16: 5

- Asia: 2010/11: 25, 2011/12: 13, 2012/13: 16, 2013/14: 15, 2014/15: 13, 2015/16: 5

- Eastern Europe and FSU: 2010/11: 2, 2011/12: 3, 2012/13: 6, 2013/14: 5, 2014/15: 14, 2015/16: 8

- Global: 2010/11: 30, 2011/12: 5, 2012/13: 6, 2013/14: 1, 2014/15: 3, 2015/16: 1

- Latin America and Caribbean: 2010/11: 22, 2011/12 12, 2012/13: 15, 2013/14: 8, 2014/15: 1, 2015/16: 4

- Middle East: 2010/11: 15, 2011/12: 4, 2012/13: 11, 2013/14: 19, 2014/15: 8, 2015/16: 12

Over the evaluation reference period, START implemented projects in some countries that have not been in conflict or at risk of conflict, nor even fragile by international standards (e.g. Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Moldova, Paraguay etc.), while at the same time reducing programming in other countries and regions (i.e. East and West Africa) seriously affected by instability and conflict. During the same period, START also programmed in domains such as counter-terrorism, anti-crime, humanitarian mine action, social/welfare services, reproductive health care, medical services, human rights, which, though tangentially related to its mandate, fall within the purview of other departmental programs, such as the Anti-Crime Capacity Building Program (ACCBP), the Counter Terrorism Capacity Building Program (CTCBP) or GAC’s ODA Program, to name a few.

Some stakeholders expressed concerns with START implementing projects that could be perceived as humanitarian aid and potentially undermine the political neutrality of humanitarian initiatives. Specific examples referred to GPSF-funded projects for refugee camps in Jordan.

Thus, while START and GPSF have been consistent with and supportive of the GC’s international security agenda and its geographic and thematic priorities, aligning programming with these broader priorities has occasionally led START and GPSF to deviate from their core areas of focus and competence.

6.3 Relevance Issue #3: Consistency with Federal Roles and Responsibilities

Finding 5: International security is the responsibility of the federal government, and GAC is the logical institutional home for START and GPSF.

As remarked in the preceding finding, addressing international security challenges to Canada and its allies is one of GAC’s key strategic priorities. In the latest iteration of the Department’s mandate letters, the GC commits GAC, to “working with the Minister of National Defence, to increase Canada’s support for United Nations peace operations and its mediation, conflict prevention, and post-conflict reconstruction efforts.” Thus, while other departments also respond to threats to Canadian and international security interests, GAC has the lead role in shaping and implementing policy and programming intended to address those threats.

Despite the challenges noted in the preceding findings, GAC remains the only department with the requisite authority and capacity to monitor crisis situations, plan for and rapidly deliver integrated policy and programming responses to crisis situations, drawing upon the collective contributions of OGDs in a coordinated fashion. More specifically, with its network of missions abroad, GAC is uniquely positioned within the GC to provide whole-of-government operational support and coordination to Canadian interventions in response to international crises. These factors considered, GAC remains the logical departmental home for START and GPSF.

7.0 Evaluation findings: Performance

7.1 Achievement of Expected Outcomes

The following sections will focus on the performance of START and GPSF, and the factors that have contributed to, or prevented the achievement of expected program results, such as program design, project monitoring, measuring and reporting on results.

7.1.1 Measurement of Immediate and Intermediate Results

Finding 6: START has made progress towards achieving outputs and immediate outcomes at the project level; however, it lacks a methodology to systematically track and measure project achievements and their contribution to program-level outcomes.

Direct observations and evidence collected during the field visits indicated that most projects have achieved their immediate and intermediate outcomes, however, there was little or no reporting on how these project results have contributed or are contributing to the overall program-level outcomes. For projects that were not visited, information was collected through a desk review of the project sample. The analysis and summary of results was challenging due to a number of factors, such as, but not limited to, the lack of:

- annual reports on program achievements by theme, region or country produced after 2012;

- a systematic collection and recording of lessons learned and good practices from implemented projects;

- strategic planning frameworks to inform programming in priority areas and/or countries, which has led to project results being reported on an anecdotal or ad hoc basis without a link to the higher order outcomes at the program level.

The detailed desk review of the project sample showed that about two-thirds (57 out of 84) of the projects demonstrated some progress toward immediate outcomes. Of the remaining projects, 14 were still ongoing at the time of review and therefore had not yet achieved outcomes, and 13 projects did not have final reports and/or relevant performance data available.

A number of limitations were considered in the process of assessing the project and program-level results based on the sample, such as:

- Delays in the approval process after 2011 made it harder for START to respond in a timely way to identified needs and to support longer-term projects.

- Short-term renewals of spending authorities and lack of multi-year funding after 2013 prevented the program from implementing longer-term projects. Most projects implemented under short time frames (less than one year) could not demonstrate or report on achievement of intermediate outcomes.

- Outcomes labeled as “intermediate” in some of the reports were actually immediate-level results.

- Intermediate outcomes as presented in the START logic model often overlapped. For example, by partnering with UN agencies and international organizations to build and strengthen the capacity of national governments in affected states (Outcome 1), START also contributes to strengthening national and international frameworks and their capacity to respond to crises (Outcome 4).

- Many projects contributed to more than one outcome; however, that was seldom cross-referenced in the results reporting sections

- For a number of projects, information has been mechanically entered in the database to allow for project closing or for moving the project to the next stage, e.g., achieved outcomes were often just a copy-and-paste of the planned outcomes without any supporting qualitative or quantitative data.

- In the cases when outcomes were affected by multiple external actors and factors, results could not solely be attributed to GPSF projects, and were not assessed through a contribution analysis.

- Many projects did not have gender-related results and indicators, or sex-disaggregated data.

- There were no specific codes, classifications or parameters for “SGBV” projects; therefore it was hard to measure START’s contribution to reducing sexual violence in conflict or other related outcomes.

In order to measure outcomes achieved by START at the program level, the evaluation grouped the projects under the outcomes that were identified. Aggregated results were assessed under each of the four “Results Stories” defined in the START logic model and summarized in the table below.

| Ultimate Outcome | Effective Stabilization and reconstruction in affected states | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intermediate Outcomes | Strengthened institutions and civil society in affected states (Results story #1) | Strengthened GC responses to crisis situations (Results story #2) | Strengthened international responses to specific crisis situations (Results story #3) | Strengthened international frameworks in use for addressing crisis situations (Results story #4) |

| Immediate Outcomes | Enhanced institutional and civil capacity in affected areas | Enhanced capacity for GC responses | Enhanced capacity for international responses to specific crisis situations | International agreements on crisis response frameworks |

7.1.2 Intermediate Outcome #1: Strengthened Institutions and Civil Society in Affected States

Finding 7: START projects have contributed to increased capacity of state institutions and civil society organizations to address the drivers of instability, manage conflict and deliver services that help restore stability and security in a number of fragile and conflict-affected states.

Projects aimed at strengthening institutions and civil society in conflict-affected states accounted for the largest share of GPSF disbursements over the evaluation period. Though implemented by third-party delivery organizations, state institutions were the primary beneficiaries of GPSF programming, which, for the purpose of results assessment, were loosely grouped under the three conventional branches of government: legislative, executive and judicial. Additionally, for reporting purposes, achieved results were grouped under three broad thematic headings: i) advancing democracy and peacebuilding; ii) security systems management; and iii) judiciary, transitional justice and reconciliation.

i) Advancing Democracy and Peacebuilding: Increased capacity of legislatures, political parties and civil society organizations

GPSF projects classified under this theme aimed at strengthening the capacity and engagement of legislatures, political parties and civil society organizations. Projects broadly aligned with the legislative branch of government typically focussed on promulgating the merits of participatory and democratic forms of governance and on strengthening the institutional mechanisms supporting democracy. In the taxonomy of START, such projects were categorized under a number of sectors: “Democratic Participation and Civil Society“; “Legislation and Political Parties”; “Civilian Peacebuilding and Conflict Prevention and Resolution”; “Decentralization Support to Sub-National Governments”; “Media and Free Flow of Information,” and “Elections.” Forms of assistance and activities commonly included curriculum development, hosting of workshops, training, and provision of material support for elections. START also funded initiatives designed to facilitate citizen participation in electoral processes and to build local monitoring capacity. The specific results achieved, based on the project review, are summarized as follows:

- Increased understanding of democratic forms of governance, such as federalism and decentralization: GPSF projects provided training on federalism (Burma, South Sudan), decentralized service delivery and citizen participation in local governance (Tunisia), which has led to increased ability of state institutions to address the diverse interests of sub-national groups through peaceful negotiations. A good example is the Forum of Federations’ (FoF) project in Burma, funded by GPSF, which delivered federalism training across Burma for representatives of ethnic political parties running for seats in the national parliament. The purpose of the training was to help demystify and legitimize the concept of federalism, particularly among the governing Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP). Even though results achieved could not be solely attributed to START’s funding, feedback received during the evaluation site visits indicated that Canada’s projects have contributed to a shift in the understanding of federalism. Federalism in Burma, which has been until recently associated with ethnic division and secessionist movements, is now being seen more as a toolbox that could yield options to help resolve Burma’s six decades of conflict between the central government and ethnic armed groups.

Even though many countries still need substantial assistance in their transition to a functioning democracy, GPSF-funded projects could be credited for contributing to results such as:

- Increased capacity of political parties to participate in elections and promote awareness of citizen rights (e.g. in Burma, Tunisia, Moldova, etc.).

- Improved capacity of local observers and civil society to monitor elections in countries such as Afghanistan, Egypt, Moldova, Colombia, Tunisia and Ukraine.

- Improved capacity of journalists to cover elections and reflect issues of public interest (e.g. Egypt)

- Increased legitimacy of electoral processes and increased public awareness of voter access rights through improved voter registry and identification of instances of fraud (e.g., in Ukraine).

While the impact of START’s interventions on the course of political events in targeted countries was difficult to assess and attribute to GPSF projects alone, the evaluation found sufficient evidence indicating that, at the very least, they have contributed to a greater awareness and understanding among beneficiaries of the merits of democratic governance. For example, Tunisia, Burma and Ukraine have all demonstrated some success in transitioning to democratic rule, evidenced by an improvement in their election process and/or duly elected functional parliaments.

ii) Security System Management: Strengthened capacity of state and civil society institutions in security systems management.

Over the evaluation reference period, START has contributed to strengthening the capacity of state institutions and civil society in security system management. A considerable amount of GPSF resources have been directed to strengthen the capacity of state institutions responsible for security, namely the police, corrections, and the military. Results achieved under this intermediate outcome are summarized as follows:

- Increased ability of the national police to enforce the law and establish security in a professional way that respects human rights: Several GPSF projects in Haiti provided equipment and training to help the National Police track and investigate crimes, including SGBV-related cases. Other projects strengthened police capacity to plan and coordinate security operations (South Sudan, West Bank) and improve security in refugee camps (Jordan). START’s contributions to LOTFA helped improve financial management, operational capacity, institutional development and gender mainstreaming in the national police force. One of the most successful projects, which received high recognition by Canada’s allies, was START’s $5 million contribution to the large-scale International Criminal Investigative Training Assistance Program (ICITAP), jointly implemented with the U.S. State Department, aimed at reforming the Ukrainian police force through the provision of training and equipment. The program resulted in improved capacity to deliver police patrol services according to international standards on human rights and rule of law; increased presence and effectiveness of police patrols through the deployment of hundreds of new officers in five cities (by March 2016); and increased public confidence in the police patrol service.

- Improved conditions and capacity of prison officers: Even though START’s support to the corrections system declined over the evaluation period, a GPSF project in Afghanistan was successful in providing materials and equipment to improve the conditions in a Kandahar prison. Another project in Sudan provided administrators and guards with necessary training and technical assistance to manage correctional facilities in accordance with international standards.

- Improved operational capacity of the military: Beyond multilateral peace operations, support to the military was not a conventional area for START programming. However, during the evaluation period, START’s material support to the military in Jordan and Ukraine increased significantly. For example, since 2012, GPSF has committed over $24 million to support key security institutions such as the armed forces and gendarmerie in Jordan. GPSF also contributed to strengthening the military/police capacity to respond to the refugee crisis in Jordan. One project provided material support to enable the military to strengthen border crossing patrols and ensure safe transportation for Syrian refugees to registration centres. Another project helped increase security for refugees and aid workers in camps by improving police operations (i.e. presence and response time) through the provision of equipment and infrastructure. As a result of support from START and other donors, there have been no security incidents at the Za’atari camp in Jordan for over a year.

In partnership with DND, GPSF also provided $8.9 million in funding for four projects to deliver material support to the Ukrainian Ministry of Defense. Stakeholders reported that as a result of the equipment and technical assistance to set up a field hospital and engage in demining, the provision of critical treatment has become faster and has increased the survivability of injured persons. - Strengthened demining capacity and increased civilian safety: Mine action was historically a priority for the GC, as evidenced by the launch of the Ottawa Process in 1996 that culminated in the creation of the Mine Ban Treaty; however, Canada’s leadership in this area declined over the evaluation period due to inconsistent funding and shifting priorities. The evaluation sample included four demining projects that provided equipment, technical assistance and training to support UN and humanitarian demining efforts in Afghanistan, South Sudan and Colombia. For example, START provided over $2.5 million for humanitarian demining projects in Colombia implemented by the Organization of American States (OAS) Comprehensive Action against Anti-personnel Mines (AICMA). According to stakeholders, these projects achieved significant results including: strengthened capacity of 132 humanitarian de-miners; improved compliance with international practices and standards; greater community awareness about mine risks; reduced number of mine-related casualties; safer access to agricultural land; and increased access to government services for 66 mine victims.

The evaluation team also had an opportunity to directly observe the effectiveness of some demining projects implemented over the past two years in Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam. Two distinct types of clearance were reviewed during the site visits: unexploded ordnance (UXO) in Laos and Vietnam, and anti-personnel and anti-tank mines in Cambodia. A key observation from the mine action programming reviewed in Southeast Asia (SEA) was the positive profile that Canada has gained by assisting clearance activities in the region and the expressed gratitude by government representatives and partners in Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam for Canada’s contributions. Relative to other programming fields, the objectives and results of mine action programs were straightforward and verifiable in numbers (e.g. explosive remnants of war (ERW) removed / land released etc.). START partners and implementers demonstrated a high degree of efficiency and professionalism, all incorporating a highly regimented set of criteria and processes in their day-to-day work while continually increasing the efficiency of land clearance through innovations in technical and non-technical surveys. - Increased effectiveness in the area of Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration (DDR): In the past, START had made some significant contributions in the area of DDR (primarily in South Sudan, DRC, Mali and Colombia); however except for Colombia, funding for DDR activities declined over the evaluation period START’s efforts and contributions to DDR remained consistent only in Colombia. START’s support for DDR in Colombia began in 2004 through the OAS Mission to Support the Peace Process (MAPP) and GPSF-funded projects have since contributed to better monitoring of the demobilization process, strengthened capacity of national/local institutions, and improved reintegration services such as education for ex-combatants.

While all individual projects quoted above were found to be successful, overall programming under the Security Systems Management theme has been uneven during the evaluation reference period, with marked declines in the level of engagement in the areas of corrections, mine action and DDR.

iii) Judiciary, transitional justice and reconciliation: Increased capacity and effectiveness of judiciary and transitional justice mechanisms

Over the evaluation reference period, START allocated considerable resources in support of the judiciary. These resources were mainly used to strengthen the prosecutorial arm of the judiciary and to increase public access for particularly vulnerable groups, such as women and children, to the justice system. The forms of assistance and activities encompassed technical assistance, training, material support and infrastructure development, all in support of ensuring access to transitional justice mechanisms (criminal prosecutions, truth commissions, reparations) to address the legacy of human rights abuses.

Some of the results gleaned from the project review included:

- Strengthened capacity of judicial systems to document, investigate and prosecute human rights abuses and war crimes: Examples of GPSF contributions included an IOM project to strengthen the capacity of military justice to prosecute perpetrators of war crimes in the Congo, and a partnership with the U.S. State Department to develop an evidentiary database in Syria for a future transitional justice process. GPSF also funded a few projects implemented by UN agencies in Guatemala that developed a forensic database and trained judges/prosecutors to use DNA evidence in war-crimes trials. One project in Guatemala supported the development of records and a protocol to detect cases of violence against children, which led to a 500% increase in arrests of perpetrators, a 200% increase in the number of charges laid, and a decrease in judicial delays from 10 months to 20 days.