Archived information

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

Evaluation of the Regional Service Centres Initiative

May 2014

Table of Contents

- Abbreviations, Acronyms and Symbols

- Acknowledgements

- Executive Summary

- 1.0 Introduction

- 2.0 Evaluation Scope & Objectives

- 3.0 Key Considerations

- 4.0 Evaluation Complexity and Strategic Linkages

- 5.0 Evaluation Approach & Methodology

- 6.0 Limitations to Methodology

- 7.0 Evaluation Findings

- 8.0 Conclusions of the Evaluation

- 9.0 Recommendations

- 10.0 Management Response and Action Plan

Abbreviations, Acronyms and Symbols

- ACM

- International Platform Branch

- ADM

- Associate Deputy Minister

- AFD

- Client Relations and Mission Operations Bureau

- AFO

- Mission Client Services

- AID

- Information Management and Technology Bureau

- ALD

- Locally Engaged Staff Services

- APD

- Representation Abroad Secretariat

- ARAF

- Accountability, Risk and Audit Framework

- ARAF

- Asset and Life-Cycle Management Section

- ARD

- Physical Resources Bureau

- ASB

- Mission Business Process Innovation and Best Practices Division

- CBS

- Canada-Based Staff

- CFO

- Chief Financial Officer

- CFSS

- Canadian Foreign Service School

- CIC

- Citizenship and Immigration Canada

- CIDA

- Canadian International Development Agency

- CIO

- Chief Information Officer

- CMM

- Committee on Mission Management

- CND

- Consular Operations Bureau

- CSAC

- Common Services Charge Abroad

- CSDM

- Common Service Delivery Model

- CSDP

- Common Service Delivery Point

- DEC

- Departmental Evaluation Committee

- DFAIT

- Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade

- DFATD

- Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development

- DHOM

- Deputy Head of Mission

- DMC

- Deputy Minister Sub-Committee on Representation Abroad

- DMCO

- Deputy Management Consular Officer

- DRAP

- Deficit Reduction Action Plan

- EAC

- Evaluation Advisory Committee

- FPDS

- Foreign Policy and Diplomacy Service

- FSD

- Foreign Service Directives

- FSITP

- Foreign Service Information Technology Professional

- FTE

- Full-time Equivalent

- GoC

- Government of Canada

- HOM

- Head of Mission

- HQ

- Headquarters

- HR

- Human Resources

- IM

- Information Management

- IMS

- Integrated Management System

- IT

- Information Technology

- IWGCSA

- Interdepartmental Working Group on Common Services Abroad

- LEITP

- Locally Engaged Information Technology Professional

- LES

- Locally Engaged Staff

- LES HR

- Locally Engaged Staff Administration

- MAO

- Management Administrative Officer

- MCO

- Management Consular Officer

- MOU

- Memorandum of Understanding

- OGD

- Other Government Department

- PMI

- Procurement Modernization Initiative

- REMO

- Regional Emergency Management Office

- RSC

- Regional Service Centre

- RSCEMA

- Regional Service Centre for Europe, the Middle East and Africa

- RSCEUS

- Regional Service Centre for the United States

- SCM

- Corporate Finance and Operations

- SDS

- Service Delivery Standards

- SLA

- Service Level Agreement

- SMD

- Corporate Finance, Planning and Systems Bureau

- SOR

- Strategic and Operating Review

- SPD

- Corporate Procurement, Asset Management and National Accommodation Bureau

- SPP

- Contracting Policy, Monitoring and Operations

- SQ

- Staff Quarters

- SR1

- Strategic Review One

- SSC

- Shared Services Canada

- SWCR

- Financial Management Support Unit, Foreign Service Directives and Policy

- SWD

- Financial Resource Planning and Management Bureau

- TBS

- Treasury Board Secretariat

- US

- United States

- VCC

- Virtual Classification Committee

- ZID

- Office of Audit, Evaluation and Inspection

- ZIE

- Evaluation Division

Acknowledgements

The Evaluation Division (ZIE), Office of Audit, Evaluation and Inspection (ZID), of the Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development (DFATD), would like to extend its gratitude to the staff and management involved in the Regional Service Centres Initiative for their cooperation and to the Evaluation Advisory Committee for its indispensable guidance and advice. Special acknowledgement is extended to all stakeholders and representatives from DFATD’s mission network, from OGDs and from the British and the Dutch government departments who agreed to be interviewed for this evaluation.

Executive Summary

Introduction

The formative evaluation of the Regional Service Centres Initiative was conducted by the Evaluation Division (ZIE), Office of Audit, Evaluation and Inspection (ZID), of the Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development (DFATD), in accordance with the requirements of the Treasury Board Secretariat (TBS) Policy on Evaluation and the Department’s 5-year evaluation plan. The purpose of this evaluation was to assess the relevance and performance of the Regional Service Centres Initiative, as well as the efficiency and economy of the implementation of two Regional Service Centres (RSCs) serving Canada's missions abroad. The target audiences for this evaluation are the Government of Canada (GoC), DFATD’s Senior Management, and the management and mission clients for the RSCs.

Background

The Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade (DFAIT)Footnote 1 is responsible for the management and maintenance of Canada’s network of missions abroad, including the delivery of common services. In 2008, the Department created the International Platform Branch (ACM) to transform the management of Canada’s international platform by streamlining common service delivery for improved operational efficiencies and cost-savings. The Regional Service Centres Initiative, a key deliverable of ACM, was proposed as a means of streamlining service delivery and realizing cost-savings while responding to increased demand for common services.

According to the Regional Service Centres Initiative, common services delivered through RSCs were to include financial, human resources for Locally Engaged Staff (LES), information management and technology, procurement and contracting, and property management services. RSCs were to apply regional approaches to common service delivery and process routine, repetitive financial transactions on behalf of their mission clients to maximize economies of scale and improve efficiencies. Ongoing cost-savings and improvements to client satisfaction were expected as well as improving the quality and timeliness of common service delivery by locating decision-makers and subject-matter experts in the field and closer to their clients.

To date, two RSCs have been established: the Regional Service Centre for Europe, the Middle East and Africa (RSCEMA) and the Regional Service Centre for the United States (RSCEUS). RSCEMA was established in March 2011 in Thames Valley near London, UK. RSCEUS was established in April 2010 at Canada’s existing embassy in Washington, D.C.

Evaluation Scope and Objectives

The evaluation covers the period from the launch of the Regional Service Centres Initiative in 2009 to March 2013 when data collection was completed. The objective of this evaluation was to provide senior management at DFAIT with an evidence-based assessment of the relevance and performance of RSCEMA and RSCEUS, in accordance with the 2009 TBS Policy on Evaluation. Additional emphasis was placed on assessing the extent to which the implementation of the RSCEMA and RSCEUS is on-track to achieve its performance targets for expected cost-savings, standardized service delivery processes, improved client satisfaction and increased quality, timeliness and efficiency of client service delivery to missions abroad.

Key Considerations

The implementation of RSCEMA and RSCEUS is not yet complete and their performance has been complicated by contextual factors, such as the roll-out of Deficit Reduction Action Plan (DRAP) initiatives. Given that the RSCs have been established for one or two years and full achievement of their intended long-term results cannot reasonably be expected, the evaluation places emphasis on the RSCs’ activities, achievement of outputs and progress toward expected outcomes. The evolution of the regional model for common service delivery was also considered in the analyses, but the evaluation primarily assesses the relevance and performance of RSCEMA and RSCEUS against criteria identified in the original business case that was developed at the outset.

Evaluation Approach and Methodology

This evaluation relied on multiple sources of evidence to assess the core evaluation issues and objectives, including: document and file review; key informant interviews with key interlocutors at HQ and client missions; financial analyses; a survey of common service clients across the mission network; and field visits to RSCEMA and RSCEUS, and to client missions in London, Berlin, and Dublin for the Europe, Middle East and Africa Region, and visits to client missions in Miami, Los Angeles and San Francisco for the US.

Key Evaluation Findings

The regionalization of common service delivery is widely recognized across the Department as an opportunity to consolidate expertise, identify efficiencies and improve productivity. The Regional Service Centres Initiative has responded to a demonstrable need to standardize service delivery processes and improve the consistency of common service delivery across the mission network. In addition, the RSCs are aligned with federal priorities and DFATD has a role and responsibility to deliver regionalized common service delivery. However, changes in the operational environment of the Department have greatly reduced the potential for RSCs, in particular RSCEMA, to achieve efficiencies and cost-savings as originally intended. Furthermore, the regional common service delivery model for the RSCs was predicated on anticipated growth in the number of positions at missions abroad, which has not materialized due to pressures created by ongoing cost-cutting exercises. Given the current environment of fiscal restraint, there is need to reconfigure the role of RSCs in implementing the regionalization of common service delivery.

Based on findings and conclusions, the evaluation recommended the following:

Recommendation #1: The Department should reassess the business case for the Regional Service Centres Initiative and make the necessary course corrections in the regionalization of common service delivery that would result in the achievement of targeted cost-savings, expected outcomes and improvements in client satisfaction.

Recommendation #2: The Department should develop a comprehensive implementation plan for the regionalization of common service delivery.

1.0 Introduction

The Evaluation Division (ZIE) at the Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development (DFATD) is mandated by the Treasury Board Secretariat (TBS) through its Policy on Evaluation (effective 1 April, 2009) to conduct evaluations of all direct program spending of the Department, including Grants & Contributions programs. ZIE reports to the Departmental Evaluation Committee (DEC), which is chaired by the Deputy Ministers and the Associate Deputy Minister of the Department.

The Formative Evaluation of the Regional Service Centres (RSC) Initiative is part of DFATD’s approved Five-Year Evaluation Plan. Consistent with TBS Policy, the purpose of this evaluation was to assess the relevance and performance of the Regional Service Centre for Europe, Middle East and Africa (RSCEMA) and the Regional Service Centre for the United States (RSCEUS), as well as the efficiency, effectiveness and economy of their implementation. The evaluation was led by ZIE and supported by two consulting firms that implemented the client survey and conducted the cost-savings analyses for the evaluation. The target audiences for this evaluation are the Government of Canada (GoC), DFATD’s Senior Management, the management and mission clients for RSCEMA and RSCEUS, and the Canadian public.

1.1 Background and Context for the RSC Initiative

In 2007, the GoC initiated a Strategic Review (SR) exercise that involved a rigorous review of government spending to increase alignment with priorities and deliver improved results for Canadians. This exercise prompted departments to identify means of enhancing the effectiveness and efficiency of program and service delivery. In response to this exercise, the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade (DFAIT)Footnote 2 submitted a proposal to transform the activities of the Department and strengthen Canada’s international platform abroad. DFAIT’s International Platform Branch (ACM) was created in 2008 to centralize and streamline common service delivery abroad as part of this SR proposal and the Department’s Transformation Agenda. The Regional Service Centres (RSC) Initiative was identified as a key deliverable of the Transformation Agenda and was situated within ACM to facilitate regionalization of common service delivery abroad.

Under the previous common service delivery model, missions were resourced in accordance with their annual reference levels to deliver common services directly to their clients and partners. Each mission would liaise individually with functional bureaus and divisions at headquarters (HQ) for support and decision-making. Variations in local operating environments and the absence of standardized business processes for common service delivery resulted in duplication of effort and unequal access to common services across the mission network. Expected growth in the demand along with rising costs and ongoing reductions in the funding base for common service delivery made a decentralized approach unsustainable over the long term. A new model for common service delivery was required to address existing and ongoing resource pressures experienced by missions in the field.

The Regional Service Centre Initiative was developed to streamline common service delivery across the mission network and accommodate increased demand while realizing cost-savings. To achieve this, authorities for common service delivery were to be reconfigured with decision-makers located closer to clients in the field, and routine, transactional processes were to be centralized. Currently, two RSCs have been established: the Regional Service Centre for Europe, the Middle East and Africa (RSCEMA) located in Thames Valley, a suburb of London in the United Kingdom, and the Regional Service Centre for the United States (RSCEUS) located at the Canadian Embassy in Washington, D.C. A brief overview of RSCEUS and RSCEMA is provided below.

Regional Service Centre for Europe, the Middle East and Africa (RSCEMA)

RSCEMA was the mechanism for regionalized common service delivery proposed in the Business Case for the Regional Service Centres Initiative. Europe was proposed as the location for DFAIT's first RSC based on the private sector practice of consolidating service delivery in areas with robust infrastructure and systems and access to transportation links and qualified staff. RSCEMA initially took shape when a small team of six officers established a presence in temporary offices in September 2010. RSCEMA was eventually established in a commercial park in Thames Valley, outside of London in March 2011.

RSCEMA serves a total of 77 mission clients across Europe, the Middle East and Africa. The RSC was designed to deliver financial services, human resource services for Locally Engaged Staff (LES), contracting and procurement services, property services, information technology services (IT) and information management (IM) services regionally to client missions in Europe, the Middle East and Africa. RSCEMA was intended to provide support, guidance, training, templates and tools for the regional delivery of these common services. In addition, RSCEMA was intended to process repetitive, labour intensive financial transactions to alleviate some of the administrative pressures from their mission clients

In 2011, mission groupings were created for these 77 mission clients. Under the new Common Service Delivery Model (CSDM) for finance, the responsibility for the administration of financial transactions was moved from RSCEMA to Common Service Delivery Points (CSDP). Five CSDPs were selected: Brussels, London, Berlin, Rome and NairobiFootnote 3. These CSDPs are financial operations service delivery points located in selected large missions in Europe, the Middle East and Africa that are responsible for processing financial transactions for the missions within their respective groupings. These CSDPs and their client missions were identified through consultations between RSCEMA and key interlocutors within ACM and Corporate Finance and Operations Branch (SCM) at HQ.Footnote 4

Regional Service Centre for the United States (RSCEUS)

RSCEUS was first proposed in 2009 by a working group comprised of senior representatives from groups within ACM formerly identified as the Representation Abroad Secretariat (APD) and the Mission Business Process Innovation and Best Practices Division (ASB). The working group was convened to design a model for common service delivery in the United States (US) that would improve or maintain the current level of service delivery, achieve efficiencies and minimize impacts on local resources. The working group developed a proposal for a geo-centralized model under which US missions were grouped into four service delivery points based on proximity. After three months of consultations, the "Quadrant" model for the US was presented as a potential mechanism for the regional delivery of common service that was consistent with the RSC Initiative

RSCEUS was officially established in April 2010 as part of Canada's mission in Washington. As for RSCEMA, RSCEUS was designed to deliver financial services, LES HR, contracting and procurement services, property services, information technology services (IT) and information management (IM) services regionally to these client missions in the US. In addition, it was envisioned that RSCEUS could also play a limited role in the delivery of regionalized consular and security services to missions. The RSCEUS model capitalizes on the presence of large missions that are capable of supporting regional common service delivery as well as established relationships among missions across the US. As noted above, US missions are organized around four Quadrants located at missions across the country: Los Angeles (West Quadrant) Washington (Central/South Quadrant), Miami (Central/East Quadrant), and New York (North/East Quadrant). These Quadrants were established using existing resources and budgets, and each is responsible for administrating financial services for two to three smaller missionsFootnote 5. Quadrant missions are also responsible for leading regional projects that are identified in collaboration with RSCEUS.

1.2 Mandate and Objectives of the RSC Initiative

The Minister of Foreign Affairs is mandated under the Foreign Affairs and International Trade Act to manage and maintain Canada’s network of missions abroad, including the delivery of common services abroad. In accordance with this mandate, DFAIT is responsible for supporting the common service needs of federal government departments and co-locators such as Crown Corporations and provincial governments at 179 missions located in 106 countriesFootnote 6.

Common services consist of the infrastructure, staff and services required to maintain Canada’s representation abroad. Under the Common Services Policy, use of common services provided through DFAIT services are mandatory for departments when required to support Canada’s diplomatic and consular missions abroad. Within the Department, ACM is responsible for the delivery of common services delivery and maintenance of Canada’s network of missions abroad. As part of ACM, the broader goal of RSCs is to maintain a mission network of infrastructure and services to enable the GoC to achieve its international priorities

The RSCs were created with the intention of increasing efficiency, generating cost savings and enhancing common service delivery. The service delivery model for the RSCs consolidates resources on a regional basis for services that involve standard, transaction-based processes that do not require onsite presence at missions. This model was to be implemented through reconfiguring the framework of reporting relationships, authorities and accountabilities between HQ and missions. Decision-makers, subject-matter experts and Centres of Excellence were to be located within the field and closer to clients at missions, which was meant to improve the quality and timeliness of common services delivered to client missions.

Objectives and Key Activities

The long-term objectives of the Regional Service Centres Initiative are to increase client satisfaction and increase the cost-effectiveness of client service delivery. In the business case, a performance target of 75% client satisfaction was set for the period of 6-12 months after the implementation of the RSCs but the exact timing for full implementation was not defined. It was also anticipated that the RSC Initiative would generate $3M in annual ongoing cost-savings starting in 2009-2010.

The RSCs were designed to meet these objectives through standardizing and streamlining services, procedures and applicable policies across regionalized missions. The common services planned for delivery by RSCEMA and RSCEUSFootnote 7 were determined as part of the operational planning process at DFAIT in consultation with both Missions and interlocutors at HQ.

The original business case for the Regional Service Centres Initiative proposed that the following common service activities should be delivered regionally:

- Finance;

- Procurement/Contracting;

- Property and Material Management;

- Human Resources for Locally Engaged Staff;

- Information Management; and

- Information Technology.

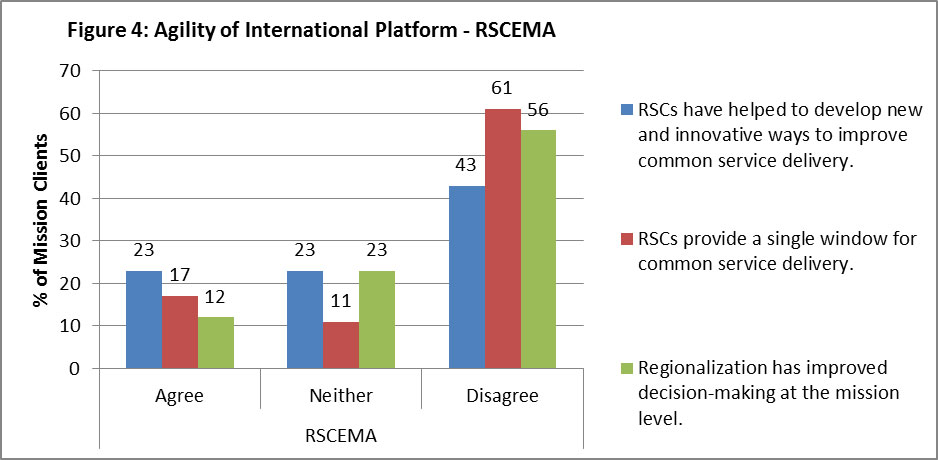

It was expected that the regional delivery of common services through the RSCs would result in a number of operational benefits to missions, including:

- Enhanced operational agility of the platform through provision of a single window for common service delivery and reduced duplication of effort;

- Reduced workload of mission personnel through the regionalization of transactional activities;

- Increased quality of management services provided through locating decision-makers and subject matter experts within the field; and

- Increased consistency in common service delivery through the establishment of standard processes and standards for service delivery.

As transactional workload and other back-office operations are shifted to the RSCs, it was intended that mission clients would have additional time and resources available to focus on value-added activities such as mission management, strategic planning and human resource development as well as new activities, initiatives and programs that would increase the effectiveness of Canada's network of missions abroad.

1.3 Governance

Governance of Common Service Delivery

ACM is responsible for coordinating the governance of operations and activities in support of Canada's Network Abroad. Common service delivery, including regionalized common service delivery through the RSCs, is managed through a series of Departmental and Interdepartmental governance mechanisms.

Deputy Minister Sub-Committee on Representation Abroad (DMC)

The DMC provides strategic direction to the department and ensures alignment between Canada’s foreign policy objectives and the Government of Canada’s international agenda. It also promotes the coordination of policy, programs and the use of common services across Canada’s International Platform. The Committee typically meets twice a year, in January and June. There are 11 federal departments and agencies represented on this committee and it is chaired by the Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs.

Associate Deputy Minister (ADM) Council on Representation Abroad

The ADM Council provides advice to the DMC on Representation Abroad. The ADM Council advises DMC on mechanisms to implement Canadian foreign policy via Canada’s international platform and monitors progress against the Departmental priorities approved by the Minister of Foreign Affairs. The ADM Council is also mandated to provide advice on the coordination of programs at missions, review resource allocation and approve standards for common service delivery abroad and promote alternatives for more cost-effective service delivery.

Interdepartmental Working Group on Common Services Abroad (IWGCSA)

The IWGSCA advises the ADM Council on Representation Abroad and provides direction and guidance on common service policy and delivery issues. This governance body is mandated to:

- manage initiatives approved by the ADM Council on Representation Abroad;

- oversee the administrative mechanisms that guide the delivery of common services abroad (e.g., the Service Delivery Standards); and

- act as a Formal dispute resolution body concerning the Interdepartmental MOU

The IWGCSA holds regular meetings to discuss issues such as the costing model, common service cost recovery and partner concerns.

Governance of the Regional Service Centres

In addition to these governance committees at HQ, regional governance mechanisms have been developed for the RSCs to provide strategic direction and support the regional delivery of common services abroad.

RSCEMA Steering Committee / RSCEUS Steering Committee

The RSCEMA Steering Committee and the RSCEUS Steering Committee are chaired by the Associate Deputy Minister of ACM, with participation from the Client Relations and Missions Operations Bureau (AFD) within ACM and the Executive Directors from the respective RSCs. A representative sample of Heads of Mission (HOMs) and Deputy Heads of Mission (DHOMs) are selected for the RSCEMA Steering Committee based on mission size, programs delivered in the region and the number of missions located in Europe, the Middle East and Africa. The RSCEUS Steering Committee is composed of all HOMs in the US and is co-chaired by the DHOM in the Canadian Embassy in Washington. Directors General from relevant Geographic Bureaus also provide advice to the two Steering Committees on the operational needs of regionalized missions from the program perspective. The Steering Committees meet quarterly and are mandated to provide advice to ACM to support decision-making on regional priorities for common service delivery and oversee the implementation of new regional initiatives in their respective regions.

Management Boards

The RSCEUS Management Board is chaired by the RSCEUS Executive Director and comprises Management Consular Officers (MCOs) and Management Administrative Officers (MAOs) in the US. Meetings are held weekly to facilitate timely recommendations on operational, policy and financial issues and to identify new opportunities for regional collaboration among missions in the US. The Management Board also convenes Regional Priority Project Teams within the US MCO/MAO community to conduct analyses and develop recommendations for regional strategies aimed to improve efficiency in common service delivery

There are no formal management boards for the Europe, Middle East and Africa region. However, regular meetings are convened by RSCEMA with the MCO/MAO community in the region to facilitate communication. These meetings are typically led by the Director of Operations of RSCEMA and are held on a monthly basis. These meetings serve a similar function as for RSCEUS by addressing operational issues for the regional delivery of common services in Europe, the Middle East and Africa.

1.4 Program Resources

Under the Common Services Policy, mandatory services provided by the RSCs are funded mainly through appropriation whereas optional services are funded by full cost-recovery through a revolving fund or net-voting authority. The Common Services Abroad Charge (CSAC) is levied to fund all incremental CBS or LES common service positions at missions staffed by DFAIT and Other Government Department (OGD) partners.

Table 1 outlines actual operating expenditures for common service delivery through RSCEMA and RSCEUS for fiscal years 2009-2010 to 2012-2013. These figures include both CBS and LES salaries as well as other operating expenditures. Total operating expenditures for the RSCs over this period totalled $10,422,091.

| Costs | 2009/2010 | 2010/2011 | 2011/2012 | 2012/2013 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a Excludes minor capital property costs. Source: Integrated Management System (IMS) b Although RSCEMA did not become fully operational until 2011, a small staff started to work out of a temporary space in 2009. c No funding was allocated for RSCEUS until 2010 when the RSC model was implemented in the US. | ||||||

| RSCEMAb | CBS Salaries | $113,961.03 | $1,158,618.87 | $1,162,870.95 | $858,219.65 | $3,293,670.50 |

| LES Salaries | $32,754.64 | $259,839.96 | $839,469.21 | $1,184,444.40 | $2,316,508.21 | |

| Other Operating | $206,147.41 | $1,046,713.00 | $945,563.00 | $1,523,760.00 | 3,722.183.41 | |

| Total | $352,863.08 | $2,465,171.83 | $2,947,903.16 | $3,566,424.05 | $9,332,362.12 | |

| RSCEUSc | CBS Salaries | n/a | $44,046.74 | $12,678.00 | n/a | $56,724.74 |

| Other Operating | n/a | $24,000.00 | $317,144.65 | $198,490.10 | $539,634.75 | |

| Total | $68,046.74 | $329,822.65 | $198,490.10 | $596,359.49 | ||

| Grand Total | $352,863.08 | $2,533,218.57 | $3,277,725.81 | $3,764,914.15 | $9,928,721.61 | |

Evaluation Scope & Objectives

2.1 Scope of Evaluation

The Formative Evaluation of the RSC Initiative covers the period from the launch of the RSC Initiative in 2009 to March 2013 when data collection was completed.

This evaluation assesses the relevance and performance of regional common service delivery in the Europe, Middle East and Africa (EMA) region and in the US, as delivered through RSCEMA in Thames Valley and through RSCEUS in Washington, respectively. The focus is on the activities and expected outputs of RSCEMA and RSCEUS, and their progress towards expected outcomes.Footnote 8

DRAP initiatives and commitments identified by the Department were not assessed in this evaluation and were considered in the analyses only where they provided context for the performance story of the RSCs. Similarly, governance and policy development related to common service delivery at HQ were not considered, other than where there are direct implications for common service delivery through the two RSCs.

2.2 Objectives of Evaluation

The objective of this evaluation was to assess whether or not RSCEMA and RSCEUS, in their current forms, provide the GoC with the best value for money in the regionalization of common service delivery.

The specific objectives of this evaluation were to:

- Assess the relevance of RSCEMA and RSCEUS by examining the extent to which they address the needs of the Department and align with GoC priorities and with DFAIT’s strategic outcomes;

- Assess the performance of the RSCs in achieving their objectives effectively, efficiently and economically with allocated resources;

- Determine whether systems, resource allocations, risk management and governance structures are adequate for the RSCs to achieve their objectives; and

- Derive lessons learned and best practices from the RSCs for consideration of RSCs in other locations

3.0 Key Considerations

3.1 Timing of Evaluation

RSCEUS was established in 2010 and RSCEMA in 2011.Footnote 9 The full achievement of longer-term outcomes is not reasonably expected since this formative evaluation is being conducted one or two years after RSCEUS and RSCEMA were created. Consequently, focus was placed on RSC activities, the achievement of outputs to date and progress towards expected outcomes. Demonstration of the efficiency and economy of the RSCs was also assessed through an examination of mechanisms intended to facilitate the core business of the RSCs, as described in planning documents.

3.2 Implementation of Common Service Delivery Points (CSDPs) and Quadrants

The evaluation assesses the relevance and performance of RSCEMA and RSCEUS against criteria outlined at the outset in the Business Case for RSCEMA and foundational documents for RSCEUS. The regional approach for common service delivery evolved, however, and Common Service Delivery Points (CSDPs) were created to implement the Common Service Delivery Model (CSDM) for finance in Europe, the Middle East and Africa after RSCEMA was established. The Quadrants in the U.S. were established at the outset of the initiative, however, as described in foundational documents for RSCEUS. The CSDPs and Quadrants were intended to improve the delivery of financial services in the regions by providing more localized expertise and administering the labour-intensive, repetitive, transactional activities related to financial processes on behalf of mission clients, in place of the RSCs as was originally planned. The development and implementation of the CSDPs and Quadrants fundamentally changed the dynamics of common service delivery in the regions, altering the role and activities of the RSCs and their interactions with client missions for financial services.

The evaluation considers the development and implementation of the CSDPs in the analyses but focuses primarily on the relevance and performance of the RSCs themselves. Financial analyses of cost-savings for the RSCs do include savings from the CSDPs but it must be noted that savings from the CSDPs were applied to DRAP commitments rather than towards Strategic Review as was originally intended for the Regional Service Centres Initiative. In effect, the savings targets for this initiative should be higher than the $3M per year for Strategic Review that are noted in the findings if DRAP savings targets are also considered.

3.3 Impacts of Organizational Change

The data collection phase occurred during a time when missions were experiencing dramatic organizational change. At the time of data collection, the GoC’s DRAP initiative was being implemented and resulted in the loss of many positions abroad in DFAIT’s program areas as well as in common service delivery. DRAP also resulted in mission closures across the network, the sale of selected Crown-owned properties and changes to private leasing policies. At some missions, MCO positions, which are held by rotating Canadian-Based Staff (CBS), were converted to MAOs, which are held by Locally Engaged Staff (LES) who do not possess the same authorities as CBS for mission operations. The implementation of the Common Service Delivery Model (CSDM) for finance was also being rolled out in the Europe, Middle East and Africa region as part of the DRAP initiative and also in the U.S. These factors had a profound impact on the dynamics within missions operations, requiring mission staff to adjust to new processes and responsibilities and changing how missions interacted with other missions, HQ and with RSCEMA and RSCEUS. Evaluation findings, therefore, must be understood in this context of organizational change.

3.4 RSCEMA and RSCEUS Comparisons

RSCEMA and RSCEUS developed in parallel to one another with different origins and local environments in which to serve. Common service areas for regional delivery are largely identicalFootnote 10, however, and core business objectives and expected targets for cost-savings and client satisfaction are shared between the two RSCs. While the assistance provided to mission clients are generally the sameFootnote 11, activities for regional common service delivery were not always identicalFootnote 12. The analyses presented in this report capture these similarities and differences. Evidence on the two RSCs is presented together when required, but data are generally presented separately for the two RSCs in order to capture the performance stories of RSCEMA and RSCEUS apart from one another.

4.0 evaluation Complexity and Strategic Linkages

As implementers of regional common service delivery, RSCEMA and RSCEUS are linked to multiple interlocutors and partners both at HQ and in the field.

Strategic linkages at HQ

RSCEMA and RSCEUS are managed through the Client Relations and Missions Operations Bureau (AFD) but accountabilities for the services delivered through the RSCs remain with other groups within the Department.

Within ACM, these include:

- Physical Resources Bureau (ARD) for property services,

- Locally Engaged Staff Services Bureau (ALD) for LES HR Services; and

- Information Management and Technology Bureau (AID) for Information Technology and Information Management Services (IM/IT).

External to ACM, RSCEMA and RSCEUS also have links with the Corporate Finance and Operations Branch (SCM) which is accountable for all financial services and activities within the Department, including in the mission network abroad. Specifically, both RSCEMA and RSCEUS work with:

- Financial Resource Planning and Management Bureau (SWD) for financial management;

- Corporate Finance, Planning and Systems Bureau (SMD) for the Common Services Delivery Model (CSDM) for finance being rolled out across the mission network; and

- Contracting Policy, Monitoring and Operations Division (SPP) for contracting and procurement.

Because RSCEUS also provides assistance in other areas, RSC activities in the US are also linked to those Bureaux and divisions within the Department with functional responsibility for consular services, security and CBS relocation services.

Strategic Linkages in the Field

RSCEMA and RSCEUS are also linked to client missions in the EMA region and in the US to whom the RSCs deliver common services. These client missions have been divided into mission groupings called Common Service Delivery Points (CSDP) for EMA and Quadrants in the US.

The RSCs are also indirectly linked to the wide network of OGD partners and co-locators clients of common services that reside at missionsFootnote 13.

5.0 evaluation Approach & Methodology

5.1 Evaluation Approach

The evaluation was managed and completed by the Evaluation Division (ZIE) within the Office of Audit, Evaluation and Inspections (ZID). An Evaluation Advisory Committee (EAC), consisting of the Director General (DG) of Client Relations and Missions Operations Bureau (AFD), the Executive Directors of RSCEMA and RSCEUS and four Heads of Mission (HOM) from selected missions in the EMA region and the US, provided guidance on the work and commented on key deliverables at each phase of the evaluation.

An evaluation matrix for the Evaluation of the Regional Service Centres Initiative was developed to outline the evaluation issues, the related questions, associated evaluation indicators, data sources, and data collection techniques. The evaluation matrix also served as the main tool for designing the data collection instruments and reporting on the evaluation findings. Footnote 14

The data collection phase of the evaluation lasted from October 2012 to March 2013. Both quantitative and qualitative data were collected through multiple lines of evidence. Experts in survey methods were commissioned to conduct a client survey. Similarly, experts in financial audits were commissioned to complete financial analyses of RSCEMA and RSCEUS costs and savings. The other modes of data collection were executed by a team of evaluators within ZIE. This team of ZIE evaluators also completed the data analyses, triangulating data collected through the multiple lines of evidence to develop findings, conclusions and recommendations, and to produce the evaluation report. Details on each of the data collection methods are provided in more detail below.

5.2 Secondary Data Collection

Document Review

Approximately 300 documents/reports were reviewed and analyzed to support this evaluation. These documents included: descriptive and analytical reports; governance documents, legislative documents; business plans; memos; briefing notes; minutes of meetings; relevant websites; and comparative studies. More specifically, the evaluators examined the following:

- Business Case for RSCEMA;

- Foundational planning documents for RSCEUS;

- Documents related to SR1 and the Transformation Agenda;

- Business process maps;

- Formal agreements (e.g., service level agreements with missions, MOUs with common service areas)

- Financial information shared by RSCEMA and RSCEUS directly and gathered through the Integrated Management System (IMS);

- Annual Reports from International Platform Branch, RSCEMA and

- Websites for RSCEMA and RSCEUS;

- Available wikis for common service areas offered at the RSCs;

- Other communication products (e.g., newsletters, samples of email messages);

- Reports from relevant surveys (e.g., ACM’s client satisfaction surveys);

- Relevant Mission Inspection reports and Evaluation reports; and

- Case studies from other regional models.

Financial Analyses

A consulting firm specializing in financial audits was commissioned to determine the cost-savings resulting from RSCEMA and RSCEUS. These analyses focused on the time period from 2010-11, when both RSCs became operational, to 2012-13, when data collection was completed. Financial data provided by RSCEMA and RSCEUS were used in these analyses to calculate cost-savings. All data related to these analyses were validated against information on position changes provided by the Mission Client Service Division (AFO) within ACM and financial data from IMS provided by the Financial Management Support Unit, Foreign Services Directives Services and Policy (SWCR-ACM). The final calculations for cost-savings and rationales for the exclusion or inclusion of costing or savings elements were validated with managers from both RSCEMA and RSCEUS.

5.3 Primary Data Collection

Key Informant Interviews

A total of 89 key informant interviews were conducted to obtain perspectives from RSCEMA’s and RSCEUS’ mission clients in the field and from key interlocutors at HQ. Interviews were conducted with HOMs and MCO/MAOs from missions in Europe, the Middle East and Africa and the US, as recommended by the EAC and selected through random, stratified samplingFootnote 15. Separate interviews were conducted with both the HOM and the MCO/MAO, except when the mission requested joint interviews. The EAC also provided guidance on appropriate officers for interview at HQ. At HQ, interviews were conducted with ADMs, DGs, Directors and managers from each of the common service areas within ACM and SCM Footnote 16. Directors General from each of the Department’s geographic regions were also interviewed to capture the impact of regional common service delivery on DFAIT’s program areas. Interviews were also conducted with senior managers from OGDs with representation abroadFootnote 17 and officers involved in the conception of the RSC model

Interviews were semi-structured and interview questions were designed to capture views on the utility of the RSCs and the impact of regional common service delivery on mission clients and program areas. Interview guides were shared with all interviewees in advance of their scheduled interview to advise key informants on the purpose and scope of the evaluation and to facilitate their preparation. Face-to-face interviews were conducted with key informants at HQ and telephone interviews were conducted with selected missions. Interviews were conducted in the interviewees’ Official Language of choice and were approximately 60 minutes in length.

Field Visits

Field visits were conducted to RSCEMA, RSCEUS and selected missions to obtain a deeper understanding of the regionalization of common service delivery through firsthand observations of operations at each RSC and their client missions. These field visits facilitated observational data of the facilities as well as providing an opportunity to conduct face-to-face interviews and focus groups with RSC officersFootnote 18 and client mission staffFootnote 19 at all levels. Where feasible, interviews were also conducted with foreign ministries to explore other regional common service models.

Recommendations for site locations for these field visits were provided by the EAC, with the aim to visit each RSC and three of their client missions. Field visits were conducted at two larger missionsFootnote 20 and one smaller mission in each region to examine the impacts of regional common service delivery for different sized missions. Field visits were 1-3 days in duration, depending on the size of the site, and were conducted between November 2012 and January 2013 to the following locations identified in Table 2 below.

Site Visits Conducted

Europe, the Middle East and Africa

Site: RSCEMA

Location: Thames Valley

Site: High Commission of Canada in the UK (Including meetings with the British foreign ministry responsible for common service delivery.)

Location: London

Site: Embassy of Canada to Ireland

Location: Dublin

Site: Embassy of Canada to Germany

Location: Berlin

US

Site: RSCEUS (Including meetings with the British and Dutch Embassies in the US)

Location: Washington

Site: Consulate General of Canada in Los Angeles

Location: Los Angeles

Site: Consulate General of Canada in Miami

Location: Miami

Site: Consulate General of Canada in San Francisco

Location: San Francisco

Client Survey

A client survey was conducted for this evaluation to obtain a broader understanding of missions’ perceptions of and experiences with regional common service delivery. A survey questionnaire was developed by ZIE and finalized by the contractor commissioned to implement the survey and deliver survey results for the evaluation report. The survey questionnaire was available in both official languages and a pre-test of the survey instrument was conducted with MCOs posted at HQ at the time of data collectionFootnote 21. All HOMs and MCOs throughout DFAIT’s mission network were invited to participate in this survey. The survey was in the field from January 25, 2013 to February 27, 2013. The final sample size for the survey was 190 respondents with a response rate of 65%.

This client survey captured mission clients’ satisfaction with common service delivery through RSCEMA and RSCEUS, missions’ experiences with their RSCs, and missions’ perspectives on regionalization and its impacts. Survey questions were specific to the different common services delivered through the RSCs or through HQ to facilitate comparisons across different groupsFootnote 22. Respondents were asked to report their level of agreement or satisfactionFootnote 23 to a series of statements regarding common services delivered through the RSC or on regionalization in general. Likert scales were used to measure levels of agreement or satisfaction and, as required, mean scores were calculated to test for statistically significant differences across groups at a 95% confidence level.

6.0 limitations to Methodology

The evaluation was limited by the lack of performance information. Scoping exercises at the beginning of the evaluation process pointed to a lack of relevant performance data available to capture the performance story. Performance indicators were identified as part of the RSCEMA Business Plan and RSCEUS’ Framework Agreement, but there was no evidence demonstrating that these data were collected consistently. As well, there is no central depository of performance data on common service delivery within the Department that could help inform this evaluation. Although some survey data from ACM were available, these surveys were intended to address corporate reporting objectives and did not provide full performance information for this evaluation. Moreover, response rates for some of these surveys were too low to support reliabilityFootnote 24. Therefore, primary data were collected for this evaluation using both quantitative and qualitative methods.

This evaluation was also challenged by difficulties in obtaining complete financial information for regional activities. While RSCEMA is a distinct organization with its own budget, RSCEUS does not have a separate budget and regional resources are subsumed within the mission budget for the Embassy of Canada in Washington. Costs for and savings from regional activities for RSCEUS, therefore, were not easily identifiable. The financial analyses conducted for this evaluation used the best available information at the time of data collection but results should be understood as conservative estimates.

In addition, scoping exercises suggested that mission size matters in terms of the impacts of regionalization of common service delivery. Efforts were made to include views and experiences from a representative sample of missions but requests for interview were declined by some missions because they were not yet regionalized and felt they had little to contribute to the evaluation. A variable on mission budget and number of FTEs was included in the survey to facilitate comparisons by mission size. However, there was insufficient variation in the distribution across respondents to provide meaningful survey results for comparison by mission size. Wherever possible, interviews or meetings were also requested with spokes (trade offices) during field visits to capture impacts.

7.0 evaluation Findings

7.1 Relevance Issue 1: Continued Need for RSCs

Finding #1: The assumptions underpinning the continued need for RSCEMA and RSCEUS are no longer valid.

The business case for the Regional Service Centres Initiative was premised on the need to address the rising demand for common services abroad and the increasing costs of global operationsFootnote 25Footnote 26 . Subsequent to a Strategic Review exercise conducted in 2007, a transformative initiative entitled, ‘Strengthening Canada’s Representation Abroad,” was developed and subsequently approved. Part of this initiative involved the reallocation of positions from headquarters to missions in order to enhance DFAIT’s capacity to achieve results through its overseas platform. It was expected that there would be a dramatic increase in demand for common services due to increased growth of CBS and LES positions abroad, which was projected to double or triple historic norms over a period of five years.Footnote 27

Concurrently, ACM had to adapt to successive and permanent reductions in its funding base as well as ongoing funding agreements with partners that do not account for increases in non-discretionary, market-driven costs of global operations. Footnote 28 It was determined that previous common service delivery practices would become increasingly unsustainable as demand for common service delivery increased. Furthermore, DFAIT faced significant costs associated with remediation of a shortage of common services staff abroad. The implementation of RSCEMA and RSCEUS was seen as an opportunity to address rising costs and increased demand while achieving economies of scale and greater value for money. By positioning the RSCs as a single common service window for missions, it was expected that responsiveness, timeliness and equitable access to management support would be strengthened.

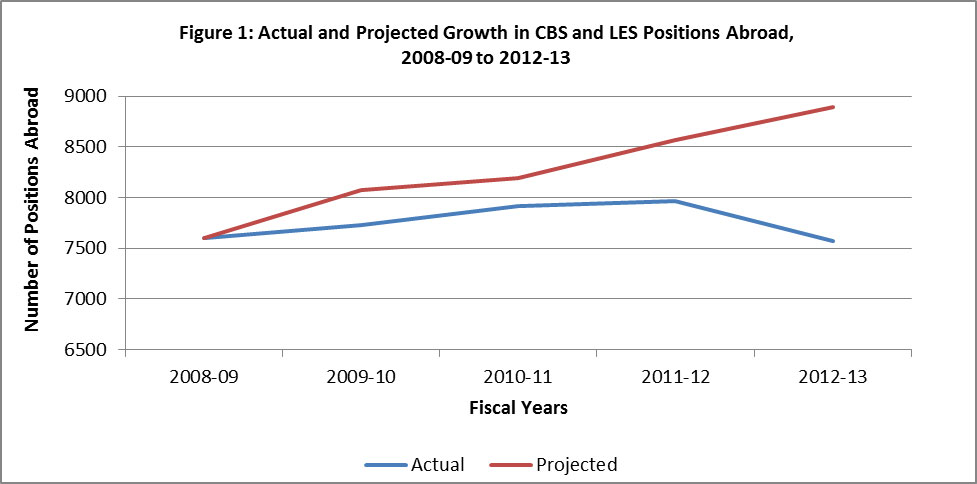

However, the projected organizational needs underpinning the business case for RSCEMA did not materialize as expected. The number of CBS and LES positions abroad increased from 7598 positions in 2008-09 Footnote 29 to a high of 7968 positions in 2011-12.Footnote 30 As of March 2013, the number of positions abroad had declined to 7571Footnote 31 as a result of position cuts identified through subsequent cost-cutting exercises, as illustrated in Figure 1. The allocation of positions abroad was first deferred due to financial pressures created by delays in the anticipated closure of certain missions abroad. Subsequently, the majority of funds that were originally earmarked for the creation of positions abroad were diverted to help meet savings targets identified as part of a subsequent cost-cutting exercise in 2012-13. Planned investments in new deployments abroad were put on hold, with some limited exceptions.

Source: Actual number of positions obtained from “International Platform Annual Report on Canada’s Network Abroad” (2008-09 to 2009-10) and “International Platform Dashboard – Canada’s Network Abroad” (March 2011, March 2012, and March 2013). Projected number of positions obtained from, “Regional Service Centre Initiative: Business Case for EMEA,” (2009).

The fact that increases in the number of CBS and LES positions abroad did not correspond with initial projections reduced the magnitude of potential cost savings that could be realized through the implementation of RSCEMA and RSCEUS. Projected cost savings were calculated based on estimates of the number of common service delivery positions that would need to be created in order to accommodate the projected increase in CBS and LES positions abroad. It was expected that the implementation of RSCEMA would result in the creation of fewer positions with an estimated cost avoidance Footnote 32 of $3.6M and therefore meet the $3M savings target identified in the Strategic Review exercise of 2007. Because representation abroad did not increase as projected, the expected savings from cost avoidance could no longer be achieved, thus calling into question the validity of one of the major assumptions underlying the creation of the regional service centres in the first place: Realization of Cost Savings.

Finding #2: RSCEMA and RSCEUS have responded to the need for increased consistency in common service delivery over the short-term.

Whereas the achievement of cost-savings and efficiencies were the primary drivers supporting the business cases for RSCEMA and RSCEUS, the Regional Service Centre Initiative also aimed to standardize business processes and promote consistency in common service delivery across missions.

The need for improved standardization and consistency in service delivery arose from inconsistencies inherent in the previous model for common service delivery. Under this model, each mission was resourced individually to deliver common services through annual reference level budgets in accordance with the Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) on Operations and Support at Missions Abroad. Variations in local operating environments and a lack of standardized business processes resulted in inconsistencies and duplication of effort across the mission network as individual missions would adopt customized administrative tools and processes to address their operational needs.

Through this “boutique model” of service delivery, missions would liaise individually with functional bureaus and divisions in HQ to obtain policy guidance, operational support and authorities for the implementation of projects and initiatives. This decentralized model of service delivery contributed to a lack of coordination and prioritization in common service delivery across the mission network. Smaller missions perceived that they were receiving a lower standard of service delivery relative to larger, high-priority missions. It was believed that regionalizing repetitive, transactional operations for common services would maximize economies of scale and increase consistency in service delivery across the network.

The business case for the Regional Service Centres Initiative proposed that delegating authorities and responsibilities for common service delivery to the field would address this need for increased standardization and consistency through the implementation of common tools, processes and service delivery standards. In accordance with the original business case, RSCEMA and RSCEUS have established regional service level agreements (SLA) with client missions that identify common service delivery processes, and set clear expectations for service delivery standards across the mission network.

Finding #3: The regionalization of common service delivery is relevant and is accepted throughout the mission network and at HQ. There are concerns, however, that RSCEMA and RCSEUS may not be the most appropriate mechanisms for implementing regional common service delivery.

Regionalization can be a mechanism for consolidating expertise, identifying efficiencies and improving productivityFootnote 33. Various areas of the Department have used regionalization to improve coordination and responsiveness in the field. For example, the Security Management Bureau relies on Regional Emergency Management Offices (REMO) to facilitate a timely response to emergencies around the globe. Trade and political programs are organized around hub and spoke models to promote coordination and facilitate program delivery. The Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) uses a decentralized program delivery model to consolidate expertise in the field and facilitate the implementation of projects in developing countries. Footnote 34

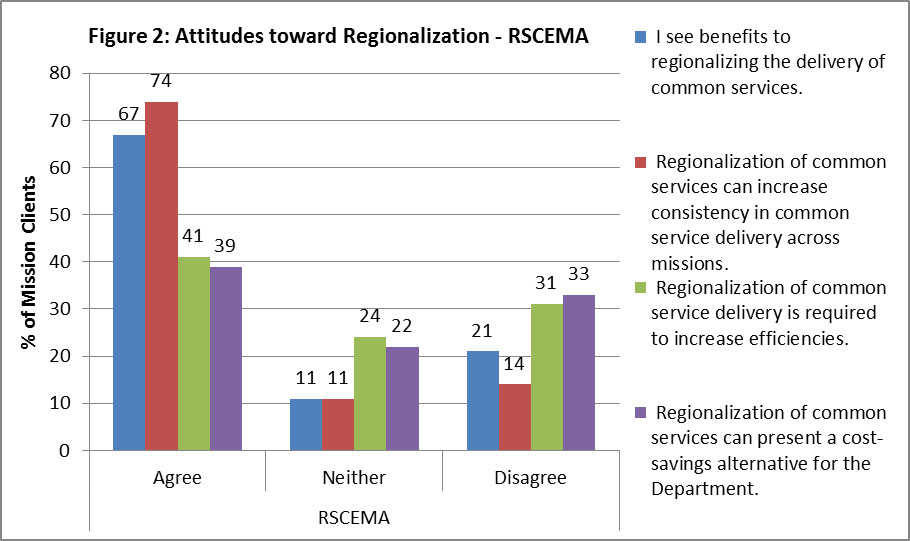

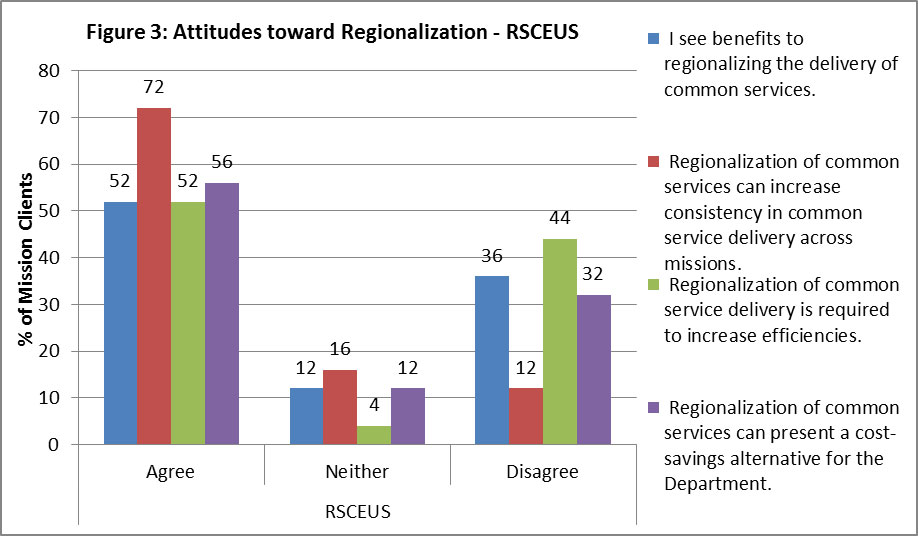

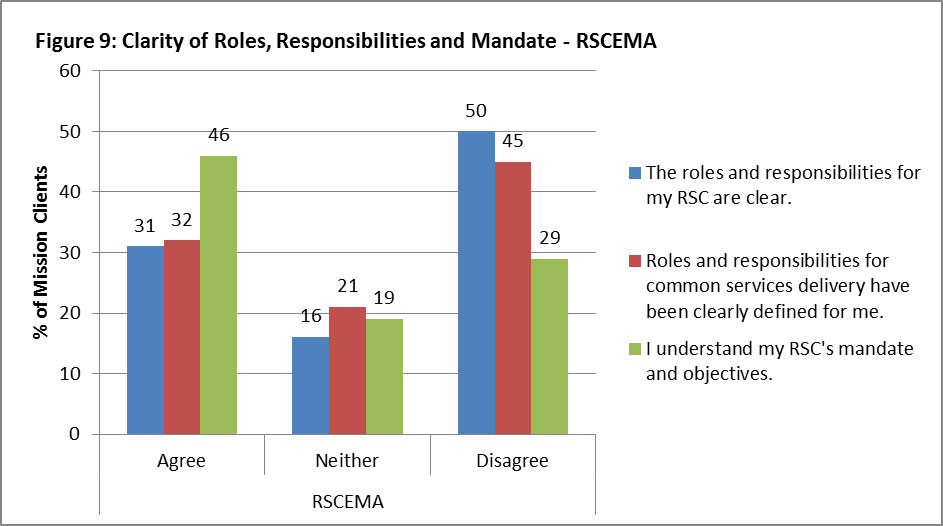

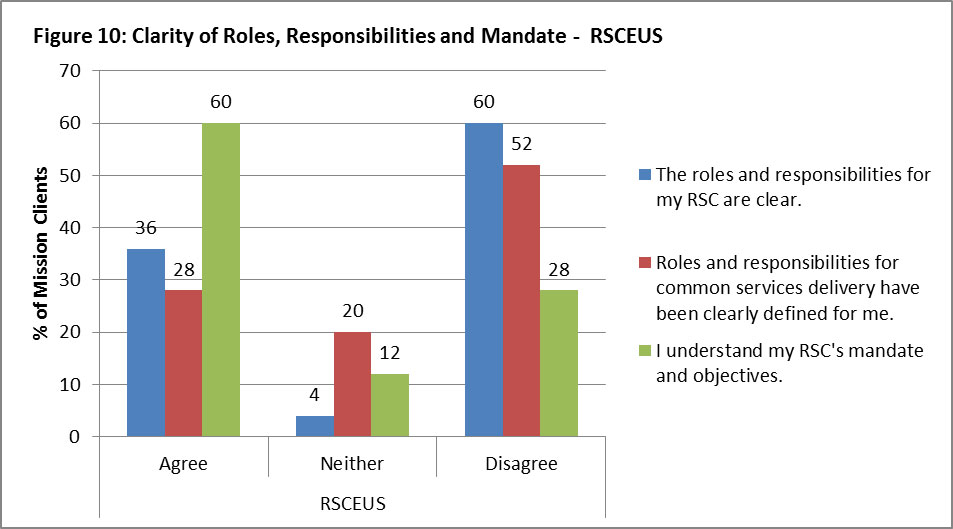

Regionalized common service delivery is widely recognized by interlocutors at HQ and missions abroad as a potential means of promoting consistency and identifying efficiencies while adapting to a shrinking resource base. Interviewees report that, given the current federal environment of fiscal restraint, regionalization of common service delivery is an opportunity for the department to “do more with less.” According to client survey results, HOMs and MCOs/MAOs located at regionalized missions agree that regionalization can increase consistency and efficiencies in common service delivery across missions, and can present a cost-saving alternative for the Department. Furthermore, more than half of survey respondents see benefits to regionalizing common service delivery, particularly among RSCEMA mission clients. (Refer to Figures 2 and 3 below.)

NOTE: Mission clients include both HOMs and MCOs. Percent of mission clients do not total 100%. Some respondents selected, “Not applicable,” or “I don’t know.” (n=91)

NOTE: Mission clients include both HOMs and MCOs. Percent of mission clients do not total 100%. Some respondents selected, “Not applicable,” or “I don’t know.” (n=25)

Common service delivery has been regionalized by both OGDs and other foreign ministries through a range of implementing mechanisms. Citizenship and Immigration Canada (CIC) contracts private firms to process most visa applications in Case Processing Centres across Canada Footnote 35. The Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs has established an arms-length Regional Service Organization that possesses delegated authority to administer financial, consular, procurement/contracting and IT support services to their network of missions abroad. In contrast, the British Foreign and Commonwealth Office has adopted a more traditional “hub and spoke” model of regional common service delivery, involving strategic service "hubs" that provide financial, HR and procurement/contracting services.

Despite the fact that regionalization continues to be relevant, interlocutors at HQ and missions abroad have raised concerns about whether or not RSCEMA and RSCEUS, in their current configurations, are appropriate mechanisms for regionalized common service delivery. Interviewees expressed concern that RSCEMA and RSCEUS may not be able to demonstrate cost-savings due to the cost of maintaining a full complement of staff abroad Footnote 36 and questioned whether maintaining regional service centres abroad is necessary given the availability of new technologies that could facilitate increased consistency and standardization from HQ. Because missions abroad are accustomed to working across different time zones, it was questioned whether increased proximity to clients would provide better value compared to service delivery from HQ or through some other model.

7.2 Relevance Issue 2: Alignment with Government Priorities

Finding #4: The original objectives for RSCEMA and RSCEUS were aligned with GoC priorities as well as DFAIT strategic outcomes.

RSCEMA and RSCEUS were core deliverables of Strengthening Canada’s Network Abroad and the Transformation Agenda, departmental priorities that sought to implement the outcomes of expenditure management exercises

In 2007, the Government of Canada introduced a new Expenditure Management System in order to better manage government spending and applied a rigorous SR exercise to government programming to help ensure value for money.Footnote 37 DFAIT’s (2007) SR1 commitments proposed that funding be reallocated to strengthen the Department’s core value-added to government operations, namely the overseas platform. This objective was to be accomplished through transformative change in DFAIT’s structure, operations and activities, including the creation of regional hubs for the delivery of accounting and HR services abroad. Footnote 38

These SR commitments were further elaborated in the 2008 Strengthening Canada’s Network Abroad submission. The original commitments under this initiative included the rebalancing of positions between HQ and missions, the renewal of common service delivery using innovative service delivery models and the regionalization of select common services such as accounting, procurement and HR services. It was further noted that an ongoing review would be conducted to identify additional common services that could be implemented through a regionalized service delivery model. The GoC’s 2008 budget confirmed that Canada’s network abroad would become more focused on the government’s foreign policy priorities and that significant reinvestments would be made in support of that vision.

DFAIT’s Transformation Agenda was a departmental initiative that was developed to implement DFAIT’s 2007 Strategic Review proposal and Strengthening Canada’s Network Abroad. One of the key objectives of the Transformation Agenda was the streamlining and modernizing of common service delivery abroad through the creation of the International Platform Branch (ACM), which integrated resources, planning and decision-making for all common service functions under a unified organizational structure. ACM is charged with delivering on the third strategic objective of the Department: maintenance of “a mission network of infrastructure and services to enable the government of Canada to achieve its international priorities.” The implementation of RSCs is one of the core deliverables identified for ACM under Sub-Program 3.1.1: “Mission Platform Governance and Common Services.”

Subsequent budgets released by the GoC have continued to emphasize the need to identify cost-savings and review administrative functions and overhead costs in support of Canada’s Economic Action Plan. The resulting change in DFAIT’s operational environment has created challenges for the implementation of some key elements of the Transformation Agenda. In 2011-12, funds previously set aside for the deployment and creation of positions overseas were reallocated to address financial pressures created by delays in the planned closure of certain missions. In 2012-13, $23.1 million of the $27.64 million frozen in DFAIT’s annual reference levels that had been allocated to implementation of Strengthening Canada’s Representation Abroad was reallocated toward the 2012-13 Strategic and Operating Review (SOR) savings targets.

The 2012-13 SOR exercise prompted a re-examination of the commitments made in the Strengthening Canada’s Representation Abroad submission. A conclusion was reached that, with some limited exceptions, it would be inappropriate to invest in new deployments abroad as per the original plans. The need to introduce a more modern operating model that reallocates resources more effectively across the global network was reaffirmed. The core objectives underlying the Regional Service Centres Initiative continue to support this need to identify cost-savings and improve the efficiency and effectiveness of common service delivery mechanisms

7.3 Relevance Issue 3: Consistency with Federal Roles & Responsibilities

Finding #5: RSCEMA and RSCEUS are consistent with federal roles and responsibilities and with DFAIT’s mandate and strategic objectives.

The management of Canada’s diplomatic and consular missions abroad is among the core roles of the Minister of Foreign Affairs set out in the Foreign Affairs and International Trade Act. Footnote 39 In support of this role, DFAIT is responsible for working “with a range of partners inside and outside government to achieve increased economic opportunity and enhanced security for Canada and Canadians at home and abroad.”Footnote 40

DFAIT is also mandated through the Treasury Board’s Common Services Policy to meet the common service needs of over 30 federal government departments and provincial government organizations throughout Canada’s network of missions abroad. Under the Common Service Policy, DFAIT is the mandatory service provider for the procurement of goods, acquisition of goods and services and management of real property when these services are required to support Canada’s diplomatic and consular missions abroad.Footnote 41 Although the mandates of other federal organizations may require some degree of international cooperation, no organization other than DFAIT is mandated to manage and maintain Canada’s network of infrastructure and services abroad.

7.4 Performance Issue 4: Achievement of Expected Outcomes

The original objectives for RSCEMA were to deliver LES HR, Finance, Property Management, Contracting and Procurement, Information Technology (IT) and Information Management (IM) Services regionally to missions in Europe, the Middle East and Africa. Similarly, RSCEUS was established to deliver the same complement of regionalized common services as RSCEMA, in addition to regionalized support for consular and security services to missions in the United States. The RSCs’ regional activities in these common service areas were expected to produce standardized business processes and formal agreements with mission clients that would improve consistency across the mission network.

It was expected that RSCEMA and RSCEUS would result in cost-savings, increased levels of client satisfaction and improved effectiveness of common service delivery abroad. Performance targets of $3M in ongoing annual cost-savings and 75% client satisfaction were established to assess the extent to which these outcomes had been achieved, with expectations that services delivered regionally by the RSCs would be rendered within established service standards.Footnote 42

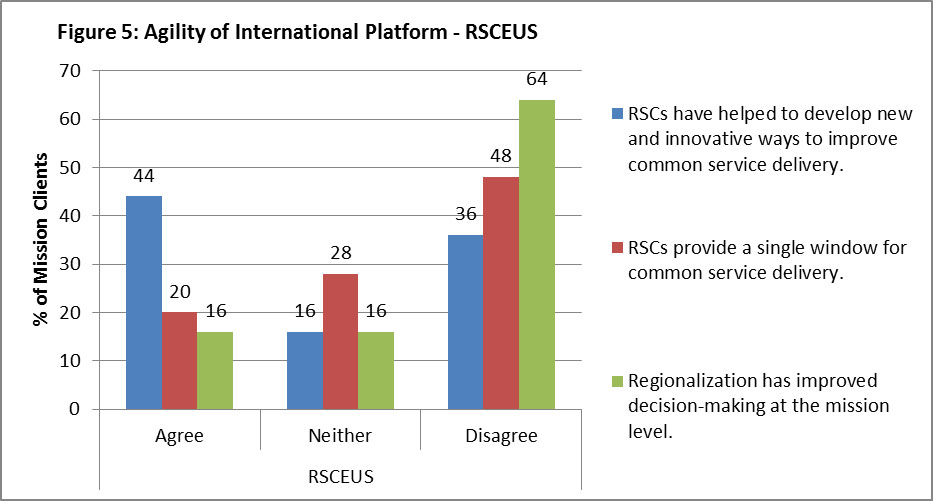

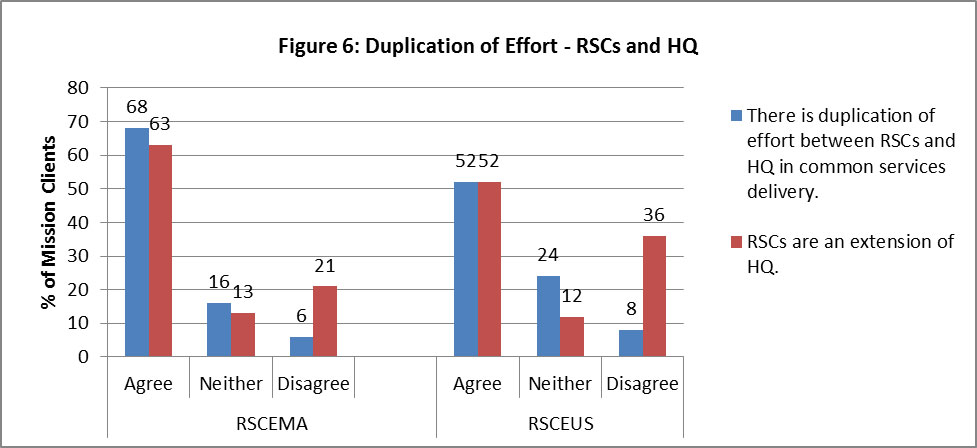

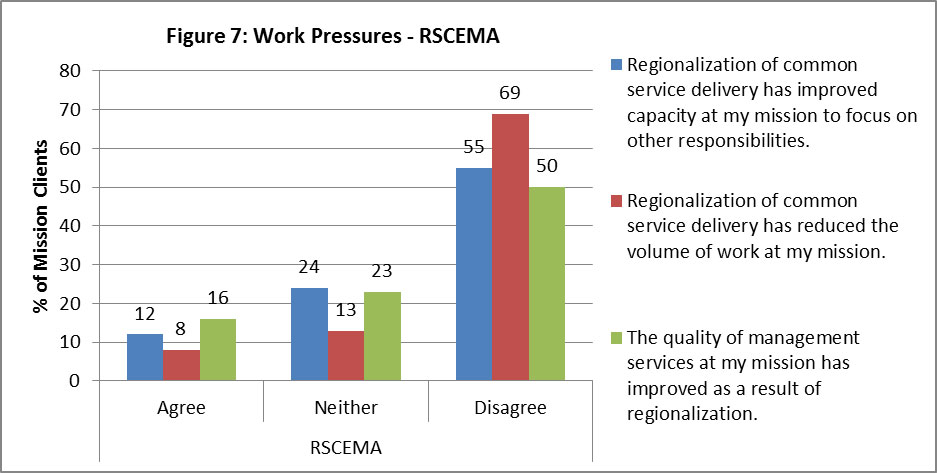

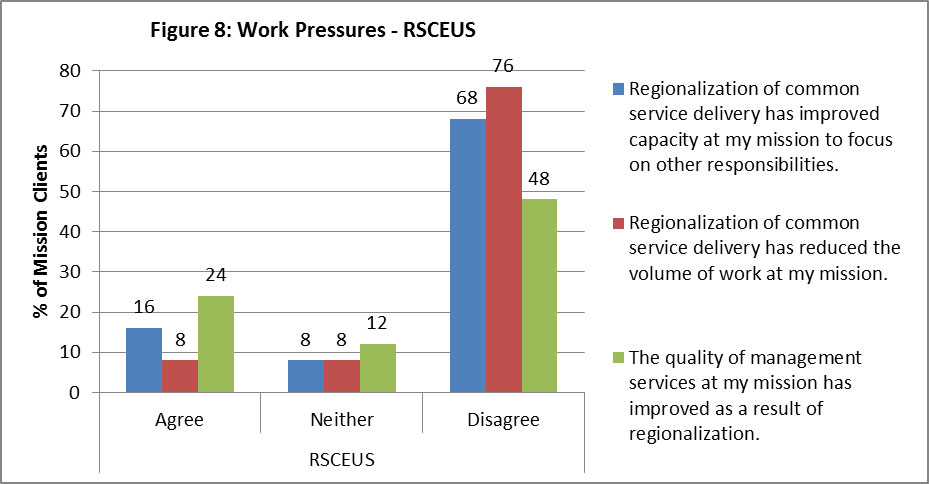

Additionally, regionalized common services delivered through RSCEMA and RSCEUS was expected to result in:

- increased agility of the international platform through consolidation of authorities and expertise at the RSCs;

- reduced workload for management staff at missions;

- increased consistency in service delivery across the mission network; and

- increased quality of management services provided to mission clients.

The progress of RSCEMA and RSCEUS toward these expected results is presented in greater detail in Findings 6 through 13 below.

Finding #6: RSCEMA and RSCEUS are not on track to achieving annual cost-savings of $3M as expected. RSCEMA and RSCEUS alone have cost the Department approximately $6.0MFootnote 43 since their creation. Ongoing costs are projected to be $0.8M per year.

The implementation of RSCEMA and RSCEUS was intended to result in a combined cost-savings of $3M per year as part of the Department’s 2007 Strategic Review commitments. The financial analysis presented in the Business Case for the Regional Service Centre Initiative estimated that RSCEMA would have a net costFootnote 44 to the department of almost $300K annually, but estimated that an ongoing savings of $3.3M for RSCEMA alone would be achieved with the inclusion of $3.6M in projected savings from cost-avoidance.Footnote 45 The calculations for cost-avoidance, however, were premised on an increase in demand for common services abroad, an assumption that is no longer valid.Footnote 46 A similar analysis was not completed for RSCEUS but it has been assumed that costs are minimized through the sharing of resources with the Canadian Embassy in Washington where RSCEUS resides. Program documentation suggests that the most significant savings for RSCEUS were to be achieved through savings in salaries and benefits resulting from the deletion of common service positions across the U.S. mission network.Footnote 47

These financial analyses consider the cost-savings for RSCEMA and RSCEUS as described in the original business case for the RSCs, which do not include the CSDPs in Europe, the Middle East and Africa. While the Quadrants were included as part of the original RSCEUS model, the CSDPs were not included in the original business case for RSCEMA but developed later as the regionalization of common service delivery evolved. Savings resulting from the CSDPs were subsequently applied to DRAP commitments. (Refer to Finding #7 for discussion of CSDPs.) Evaluation results presented here exclude DRAP savings from the CSDPs and focus specifically on those costs and savings elements related to the creation and operation of RSCEMA, RSCEUS and the Quadrants applied towards meeting their 2007 Strategic Review commitments.

| 2010-11 | 2011-12 | 2012-13 | Total | Ongoing | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Note: Savings are denoted by a negative sign. a All financial information provided by RSCEMA and RSCEUS. Details provided in Appendix 6. b Costs for RSCEMA account for positions that were deleted in the region to offset those that were created at the RSC. c Figures for RSCEMA do not include savings from creation of CSDPs in Europe, the Middle East and Africa. d Figures for RSCEUS were estimated based on best available financial information at the time of data collection. e True costs and savings for RSCEUS are not available because operating costs for the RSC are not tracked apart from the mission in Washington. f Figures denote savings elements excluding savings from creation of Quadrants in the U.S. | |||||

| RSCEMA | |||||

| Costsb | 1.45 | 1.58 | 2.46 | 5.49 | 2.23 |

| Savingsc | 0 | -0.16 | -0.24 | -0.39 | -0.35 |

| Costs/Savings for RSCEMA (excluding CSDPs) | 1.45 | 1.42 | 2.22 | 5.10 | 1.88 |

| RSCEUSd | |||||

| Costse | 0.42 | 1.17 | 1.03 | 2.62 | 1.09 |

| Savingsf | 0 | 0 | -0.07 | -0.07 | -0.84 |

| Savings from Quadrants | -0.07 | -0.37 | -1.21 | -1.65 | -1.33 |

| Cost/Savings for RSCEUS | 0.35 | 0.80 | -0.25 | 0.90 | -1.08 |

| Total Cost/Savings for RSCEMA and RSCEUS (excluding CSDPs) | 1.80 | 2.22 | 1.97 | 6.00 | 0.80 |

The financial analyses conducted for this evaluation demonstrate that, to date, RSCEMA and RSCEUS have not achieved their ongoing savings targets of $3M per year. Excluding savings attributable to the implementation of the CSDPs, RSCEMA and RSCEUS together have cost the Department $6.0M from 2010-11 to 2012-13,Footnote 48 as described in Table 3 above.Footnote 49 Furthermore, ongoing costs for maintaining the two RSCs are estimated to be approximately $0.8M per year.Footnote 50 Costs for creating and operating the co-location RSC model in the U.S. is considerably lower compared to the RSC model adopted for Europe, the Middle East and Africa. Ongoing savings are expected for RSCEUS after the Quadrants are fully implemented, which offset the expected ongoing costs for maintaining RSCEMA.

Cost Savings – RSCEMA

The results presented in Table 3 above illustrate that the cost for operating RSCEMA from 2010-11 to 2012-13 was approximately $5.1M, which does not include the one-time fit-up costs of $3.8M for the facilities in Thames Valley.Footnote 51 The ongoing cost for maintaining the RSCEMA is estimated to be approximately $1.9M per year.Footnote 52

The costs associated with RSCEMA included salaries and benefits for RSC staff (both CBS and LES), relocation costs and residential leasing costs for CBS, office leasing and operations and costs associated with regional training. The cost-savings analysis presented in the Business Case assumed savings would be achieved through reduced frequency of travel from HQ, through regional procurement and contracting, through lease rationalizations for reductions in annual lease costs for CBS in the region and through cost avoidance under the Common Services Abroad Charge (CSAC) framework.Footnote 53 Among these savings elements, however, only savings achieved through reduced travel from HQ were evident and directly attributable to RSCEMA. Savings from the regionalization of the procurement and contracting function could not be achieved as planned due to insufficient delegation of authorities from HQ to the RSCs. Savings resulting from the lease rationalization exercise was not included because, while RSCEMA’s activities have identified potential savings for the Department’s property budget, the role of RSCEMA as implementers of the exercise does not necessitate the attribution of resulting savings to the RSC. As stated above, savings from cost-avoidance were not achieved because the assumptions underpinning cost-avoidance are no longer valid.

Cost Savings – RSCEUS

For RSCEUS, the net costs of maintaining the RSC was approximately $0.9M from 2010-11 to 2012-13 and an ongoing savings of approximately $1.08M is expected.Footnote 54 However, these figures are conservative estimates for the creation of RSCEUS.Footnote 55 Accurate financial information for the RSCEUS is difficult to obtain because RSCEUS expenditures are subsumed under the budget for the Canadian Embassy in Washington, D.C. and the full operating cost for the RSC is unavailable. Program files indicate that RSCEUS reported a total of approximately $570K in expenditures from 2010-11 to 2012-13,Footnote 56 with an additional $200K in project-related costs in 2011-12.Footnote 57 Interlocutors at HQ, however, report that these figures do not capture the full cost for operating RSCEUS because the costs for regional activities are not tracked separately from the mission budget for the Embassy in Washington. Accurate financial information on true RSCEUS savings is likewise difficult to determine.

Finding #7: Common Service Delivery Points (CSDPs) were created for the Europe, Middle East and Africa region as the regional approach for common service delivery evolved. Ongoing savings of almost $1.3M are expected with the inclusion of DRAP savings from the CSDPs in the financial analyses. These projected savings, however, remain below the Strategic Review target of $3M and would not meet the expected savings required by DRAP.

The regional model for financial services entails the deletion of accountant positions at missions and the creation of finance positions at the CSDPs in Europe, the Middle East and Africa and the Quadrants in the US. In this CSDM for finance, client missions are divided into groupings that are linked to a particular CSDP or Quadrant in their respective regions,Footnote 58 and financial transactions for client missions in each grouping are processed through their respective CSDP or Quadrant. These CSDPs and Quadrants were intended to improve effectiveness and efficiency for financial services through more localized expertise than was possible through the RSC, particularly for RSCEMA.Footnote 59 This new regional model for finance removed the repetitive, transactional activities involved in the processing of vendor payments and administration of financial services away from the RSCs to the CSDPs and Quadrants. The creation of these CSDPs and Quadrants as delivery points for financial services effectively shifted the role of the RSCs from processing centres, as originally envisioned, to proposed centres of expertise and financial management.

These analyses assess the total cost-savings for the Department, including the CSDPs in the Europe, Middle East and Africa regions. The identified savings from the implementation of the CSDPs are most appropriately analyzed separately from the other savings elements for the RSCs because the evaluation assesses the relevance and performance of the RSCs against criteria described in the original business case, because the original business case stipulates that the RSCs were established to meet 2007 Strategic Review commitments and because projected savings from the CSDPs were committed towards DRAP savings. The analyses presented in Table 4 below, however, incorporate the CSDP savings for DRAP to illustrate the full cost-savings for the Department as the regionalization of common service delivery evolved. Of note, committing savings from the CSDPs to DRAP effectively increased the total savings targets that the initiative was required to meet, beyond the ongoing $3M in savings per year outlined in the 2007 Strategic Review.

| 2010-11 | 2011-12 | 2012-13 | Total | Ongoing | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|