Archived information

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

Evaluation of Canada’s Development and Humanitarian Assistance Programming in West Bank and Gaza

2008-2013

Synthesis Report

July 2015

Acknowledgments

The Development Evaluation Division would like to thank all those who contributed to this evaluation. The West Bank, Gaza and Palestinian Refugee program team and other programs working in the region provided invaluable support throughout the process. We especially thank those that hosted the field missions and facilitated data gathering.

We would like to acknowledge the work of the team of consultants from the Consortium of the Canadian firms DADA International, Salasan International and Project Services International: Keith Ogilvie (team leader), Peter Hoffman and Pamela Branch, and in the West Bank and Gaza, Marisa Consolota Kemper and Ayman Daraghmeh.

Thank you to Dr. Pierre Beaudet, Associate Professor from the University of Ottawa, for his expert peer review of the evaluation.

From the Development Evaluation Division, the evaluation was managed and supervised by Gabrielle Biron Hudon and Andres Velez-Guerra respectively.

James Melanson

Head of Development Evaluation

List of Acronyms and Abbreviations

- ACR

- Annual Country Report

- AGO

- Attorney General’s Office (PA)

- AHLC

- Ad Hoc Liaison Committee

- ATC

- Anti-Terrorism Clause (DFATD contractual requirement)

- BMZ

- German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development

- CAP

- Consolidated Appeal Process

- CDPF

- Country Development Programming Framework

- CEAA

- Canadian Environmental Assessment Act

- CERF

- Central Emergency Relief Fund

- CFLI

- Canada Fund for Local Initiatives

- CHAP

- Common Humanitarian Action Plan

- CIDA

- Canadian International Development Agency (now part of DFATD)

- CSO

- Civil Society Organization

- DB

- Doing Business (World Bank Doing Business Reports)

- DFAIT

- Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade (now part of DFATD)

- DFATD

- Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development

- DND

- Department of National Defense

- ECHO

- European Commission Humanitarian Aid and Civil Protection Office

- EMP

- Environmental Management Plan

- EU

- European Union

- FAO

- Food and Agriculture Organization

- FPCCIA

- Federation of Palestinian Chambers of Commerce, Industry and Agriculture

- FY

- Fiscal Year

- GDP

- Gross Domestic Product

- GHD

- Principles of Good Humanitarian Donorship

- GIZ

- German Society for International Cooperation

- GPB

- Geographic Programs Branch (CIDA/DFATD)

- HA

- Humanitarian Assistance

- HJC

- High Judicial Council (PA)

- ICRC

- International Committee of the Red Cross and Red Crescent

- IDRC

- International Development Research Centre

- IHA

- International Humanitarian Assistance Directorate, MGPB

- ITC

- International Trade Centre (UN)

- LACS

- Local Aid Coordination Secretariat

- LDF

- Local Development Forum

- MDGs

- Millennium Development Goals

- MGPB

- Multilateral and Global Partnerships Branch (CIDA/DFATD)

- MMEP

- McGill Middle East Programme

- MoA

- Ministry of Agriculture (PA)

- MoI

- Ministry of Interior (PA)

- MoJ

- Ministry of Justice (PA)

- MoNE

- Ministry of National Economy (PA)

- MoSA

- Ministry of Social Assistance (PA)

- NDP

- National Development Plan

- NGO

- Non-Government Organization

- OCHA

- Office of the Coordinator of Humanitarian Affairs (UN)

- ODA

- Official Development Assistance

- OECD DAC

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development – Development Assistance Committee

- OQ

- Oxfam-Québec

- PA

- Palestinian Authority

- PAD

- Project Approval Document

- PalTrade

- Palestinian Trade Centre

- PCBS

- Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics

- PIP

- Project Implementation Plan

- PJI

- Palestinian Judicial Institute

- PLC

- Palestinian Legislative Council

- PMF

- Performance Measurement Framework

- PRDP

- Palestinian Reform and Development Plan

- PSCC

- Private Sector Coordination Council

- PSD

- Private Sector Development

- PSDP

- Private Sector Development Program (GIZ Program of which Framework Conditions is part)

- PWCB

- Partnership with Canadians Branch (CIDA/DFATD)

- RBM

- Results Based Management

- RCMP

- Royal Canadian Mounted Police

- REEWP

- Regional Economic Empowerment of Women Project

- ROC

- Representative Office of Canada in Ramallah

- SEG

- Sustainable Economic Growth

- START

- Stabilization and Reconstruction Task Force

- TORs

- Terms of Reference

- UN

- United Nations

- UNCTAD

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development

- UNDP

- United Nations Development Programme

- UNICEF

- United Nations Children’s Fund

- UNODC

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime

- UNOPS

- UN Office for Project Services

- UNRWA

- United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestinian Refugees

- WFP

- World Food Program

Executive Summary

This report presents the findings, conclusions and recommendations arising from the Evaluation of the Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development (DFATD) Development and Humanitarian Assistance Programming in West Bank and Gaza from 2008-2009 to 2012-2013. The evaluation was carried out between November 2013 and August 2014, with a field mission in March 2014. In addition to a substantial body of program documentation, 25 sample projects were reviewed in the priority sectors of justice, private sector development and humanitarian assistance.

Context

Although not a country, West Bank and Gaza are together classified as fragile in development terms, with a history of conflict and ongoing political instability. Over the evaluation period governance was divided between West Bank and Gaza, and the Palestinian Legislative Council has not met since 2007. Canada and most other donors consider Hamas, which controls Gaza, to be a terrorist organization and view the Fatah-supported Palestinian Authority (PA) in West Bank as the preferred development partner.

The Palestinian economy is one of the world’s most dependent on development assistance. There are structural challenges to economic growth, including limited control over West Bank land and water resources, security restrictions applied by Israel on movement of goods and people, and a lack of control over borders. Sluggish growth of the world economy and a growing shortfall in donor assistance have added to these challenges.

While some social development indicators show improvement over the past two decades (for example literacy rate, gender equality gap, maternal and child mortality rates), West Bank and Gaza continue to score low on the Human Development Index. The main social issue is unemployment, which is particularly acute among youth and women. Poverty and food security are major concerns, especially in Gaza where 70% of Palestinian refugees depend on the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestinian Refugees (UNRWA) for food.

Following the 2007 Hamas/Fatah split, the subsequent re-launch of the peace process in Annapolis in November 2007, and the Paris Donors’ Conference the same year, Canada made a commitment to provide $300 million in West Bank and Gaza development and security sector programming over five years from 2008-2009 to 2012-2013. This commitment was in support of a “comprehensive, just and lasting peace” negotiated directly between the parties. CIDAFootnote 1 disbursements in support of the government of Canada’s commitment totaled $272.6 million over the period under evaluation,Footnote 2 almost all disbursed through the bilateral program and distributed between three priority sectors: justice and governance; private sector development (PSD); and, humanitarian assistance (HA).

Findings and Conclusions

The development programming context in the West Bank and Gaza continues to be one of the most complex in the world – politically, culturally and economically. The challenges become formidable when the ongoing overhang of conflict is considered. Despite these obstacles, the evaluation evidence demonstrates that Canada’s programming in West Bank and Gaza has been designed and implemented appropriately to achieve sustainable results across its three priority sectors, although some interventions require remedial attention.

Effectiveness

The evaluation confirmed results in all three priority sectors, as seen in changes in structures, internal capacity and methods of functioning of Palestinian institutions. Humanitarian programming, despite its shorter planning and results horizon, is showing sustainable outcomes in building the institutional capacity of select Ministries of the PA, and in increasing the resilience of Palestinians to manage shocks and emergencies that result mainly from ongoing conflict.

There are three caveats to this general conclusion. First, justice and PSD sector projects have only been active for two to three years and outcome level results in the target institutions will not be evident until further in the future. Second, there is an absence of information on progress against higher level outcome targets contained in the Performance Measurement Framework (PMF) for humanitarian assistance, although there is evidence of output-level results achievement. Third, some projects will not achieve all their intended results without further adjustments.

The justice sector has achieved satisfactory results, with evidence pointing to improved capacity and functioning of rule of law institutions. However, it has also experienced shortcomings in the performance of two capital construction initiatives and will not meet the original expectations of stakeholders in the Courthouses Construction and Forensic HR and Governance projects. Despite the open communications with stakeholders that have been maintained on these projects, the expected shortfalls are creating some reputational risk for DFATD in a sector where it has been regarded as a leader. The situation was compounded by reallocation of resources in the Courthouse project which took time to effect.

The PSD sector has achieved some satisfactory results. In addition to its institution building work, Canada contributed to collective efforts to address the Palestinian Authority’s structural deficit by making two contributions to the World Bank Palestinian Reform and Development Plan Trust Fund, a budgetary support mechanism allowing the PA to continue to deliver services that will (inter alia) contribute to private sector development. Canada’s contribution was meaningful and its decision to no longer contribute to this fund has reduced both its contribution to an area of ongoing need and its influence in policy dialogue on macroeconomic issues.

In the humanitarian assistance sector, the time frames and partners are different from those of the other two DFATD priority sectors. Canadian funded humanitarian assistance has been delivered within a framework of well-established international institutions and processes and has achieved most of its objectives. Some projects have had the added benefit of contributing to institutional development within the PA. Program design is moving gradually toward support for multi-year programming which would allow for longer term impacts (such as building resilience in the population), while retaining the flexibility to respond quickly to emergency needs. This could offer opportunities for future linkages with PSD sector programming. Multi-year programming could also improve efficiency for DFATD by reducing the number and frequency of project approval processes.

Relevance

Logic models at the program and project levels are linked with Canada’s policy objective of “contribut[ing] to the creation of a viable, independent and democratic Palestinian state living side by side in peace and security with Israel as part of a comprehensive peace settlement.”Footnote 3 Building on this, the program made appropriate decisions on the level of resources devoted to the three priority sectors; the selection of organizations working on the ground as implementing partners; and, the cross-sectoral coverage offered by projects in the justice and private sector development portfolios. This internal coherence facilitated the prominence of Canadian programming with the PA and within the donor community, especially in the justice sector.

The selection of priority sectors was relevant and consistent with the priorities and needs of the PA and the Palestinian people as set out in the Palestinian Reform and Development Plan for 2008-2010 and subsequent National Development Plans. In the justice and PSD sectors, the choice to focus on building PA institutions was appropriate in light of constitutional/legal framework challenges and the need to take a long-term view on development objectives. Humanitarian assistance programming was aligned with the United Nations (UN) consolidated appeal and annual integrated humanitarian assistance planning and commitment process.

Sustainability

While only half of the projects in the evaluation sample were assessed as satisfactory in terms of sustainability, many of the influencing factors are outside the control of the program, such as the economic and political fragility associated with the ongoing conflict and the short duration of project cycles vis-à-vis institutional change processes. Continuity in programming directions combined with consideration for sustainability within projects will strengthen prospects for sustainability in justice and private sector development.

Cross-cutting Themes

The program has addressed the cross-cutting themes of gender equality, environmental sustainability and governance with a mixed record of success. There was emphasis on addressing gender issues in planning documents and to some extent in implementation of justice and PSD projects. Capacity for gender programming has been strengthened in OCHA, a central humanitarian assistance agency. However, the cultural context, limited allocation of gender equality and environment specialist resources, and possibly unrealistic expectations of what could be achieved within the project time frames have constrained gender and environment results so far. Environment received nominal attention and there is little evidence of related results in the justice and PSD sectors, although the program complied fully with Canadian Environmental Assessment Act screening requirements for the Courthouse Construction project.

Governance, on the other hand, has been fully integrated in the program. It is the raison d’être for the justice portfolio and has been an important theme in the PSD sector projects, both in terms of institutional change and improving the legal and regulatory environment for business.

Humanitarian assistance faces larger challenges in integrating cross-cutting themes, given its shorter time horizon and primary focus on meeting urgent needs such as food, water, shelter and protection. That said, the program did address cross-cutting themes in certain areas, for example by funding gender equality expertise in the central humanitarian assistance planning organization, OCHA. At the operational level, HA activities took into account gender and in some cases to environmental considerations as well.

Aid Coordination

Canada is recognized as an engaged participant in formal and informal aid coordination bodies. It is especially recognized for its strong support to coordination in the justice sector. There are nonetheless opportunities for improved coordination between some projects and other related donor initiatives.

Canada’s programming in the West Bank and Gaza has generally respected the Principles for Good International Engagement in Fragile States and Situations, and the Principles of Good Humanitarian Donorship. The program has worked to meet humanitarian needs that also align with the program priorities. However, in two of the HA projects sampled, partners noted funding changes they had not anticipated, and therefore, they perceived a lack of predictability.

Efficiency

In general, the program was delivered efficiently in terms of use of resources. Its strong field presence and use of expert resources and dedicated staff in the three priority sectors added to its visibility and credibility with the donor community and the PA. In some cases, decision-making processes – having to contend with the complexity of a conflict-affected operating context – had implications on the timing of DFATD programming.

There was little variety and hence basis for comparison between different delivery models and mechanisms. Considering the conditions on the ground and the program’s theory of change as reflected in the logic model, however, the evaluation was able to conclude that overall the choice of partners and therefore the delivery models and mechanisms were appropriate to the needs of the program. Delivery of humanitarian assistance through the bilateral program offered opportunities to link what are normally quite separate programs. This worked to the advantage of both branches, providing operational and logical coherence to DFATD’s development and HA programming in West Bank and Gaza.

Performance Management

The program’s use of results-based management and related tools at the project level has been appropriate overall, despite challenges of linking up with the systems of multilateral agencies who are acting as implementing agencies for DFATD funded projects. At the program level, there are opportunities to more systematically collect information on progress toward results achievement based on the revised Performance Measurement Framework.

Recommendations

The CIDA program to date has been responsive to Palestinian needs and Canadian priorities, has begun to show results, and has allowed Canada to establish itself as an influential donor and interlocutor with the PA. It should continue to support key Palestinian institutions in its priority sectors at the same time as it considers opportunities to expand its contribution in these sectors.

1. Canada has played a strong role in the justice sector, and there are opportunities to enhance sustainability of these investments. The program should take steps to ensure that adequate recurrent cost and specialist resourcing for physical facilities and institutions will be in place over the long-term. It should also consider ways to complement its support to facilities and institutions with commensurate support for Palestinians’ use of, and access to these institutions. Canada should use its strong presence in the justice sector to encourage inter-institutional cooperation within the PA at the operational level, until amendment of the Judicial Authority Law more formally clarifies roles and responsibilities.

2. Achievements to date in Private Sector Development (PSD) similarly offer a foundation on which to build future programming. The enabling environment for business and related institutional structures remain fragile and in need of strengthening. Consideration should also be given to more direct competitiveness initiatives with Palestinian businesses.

3. The program’s management of humanitarian assistance should continue to respect the principles of Good Humanitarian Donorship, including neutrality, focus on need, timeliness, and predictability of funding. Making sure that adopting a thematic priority is managed consistently with the principle of needs-based allocation, and that decision-making is within required consolidated appeal time frames, will ensure flexibility and timeliness in responding to identified humanitarian needs. As well, there is a particular opportunity in West Bank and Gaza to address longer term resilience of populations in the event of disaster, and Canada should look for opportunities to step up joint efforts already begun with the donor community to make this an integral part of HA programming.

4. There are particular challenges to fully integrating the themes of gender and environment in the West Bank, Gaza and Palestinian Refugee Program. The program has given these themes appropriate emphasis in the Country Development Programming Framework, and is now positioned to place greater emphasis on operational implementation. Building on the foundations laid in existing projects, the program should increase its attention (and human resources, if necessary) to more complete integration of gender and environment at program and project levels.

5. The program should ensure that clear and detailed guidance is provided to staff and partners on the application of the Anti-Terrorism Clause (ATC).

6. The program has taken steps to improve its Performance Measurement Framework (PMF) but should work with implementing partners to consolidate the links that have been lacking between project level results and reporting systems and the program PMF, especially at the outcome level. This will make annual reporting a more meaningful and useful exercise to both program and project managers. As well, the program should consider working with partners and other donors to improve data collection and outcome reporting for gender and environment.

7. There is scope for greater information sharing and coherence in the field between peace and security, development, and trade programs. DFATD should ensure that its West Bank and Gaza field operations have effective practices in place for inter-program coordination and synergy.

1.0 Introduction

This report presents the findings, conclusions, lessons learned, and recommendations arising from an evaluation of DFATD’s development and humanitarian assistance programming in the West Bank and Gaza over the period 2008-2009 to 2012-2013. This section provides an overview of the evaluation rationale, approach and methodology. Greater detail on the methodology employed is provided in Annex B.

1.1 Evaluation Rationale, Purpose and Objectives

1.1.1 Evaluation Rationale

This is the first program level evaluation carried out on the West Bank, Gaza and Palestinian Refugees Program of the Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development (DFATD).Footnote 4 It was undertaken to satisfy the Canadian government requirement for periodic evaluation of major programs.

1.1.2 Evaluation Objectives

The terms of reference for the evaluation set out several specific objectives, including:

- To assess the development and humanitarian results achieved by Canada in West Bank and Gaza between FY 2008-2009 and 2012-2013 based on established criteria for development assistance;

- To assess the extent to which the design, delivery and management of the DFATD development programming in West Bank and Gaza aligns with the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development—Development Assistance Committee (OECD-DAC) Principles for Good International Engagement in Fragile States and Situations;

- To assess the extent to which the design, delivery and management of the DFATD humanitarian assistance programming in West Bank and Gaza aligns with the Principles and Practices of Good Humanitarian Donorship;

- To assess the performance and results of DFATD’s various delivery mechanisms for development and humanitarian assistance in the West Bank and Gaza, including partnership with civil society organizations, bilateral programs, local funds and grants to multilateral organizations in a whole-of-department process;

- To identify good practices, areas for improvement and formulate lessons learned, and develop recommendations for improvements at the Corporate and Program levels; and,

- To inform future development and humanitarian assistance programming in West Bank and Gaza and other fragile states.

1.2 Evaluation Approach and Data Collection Methods

This evaluation was carried out in accordance with the Organization for Economic Development and Cooperation (OECD) – Development Assistance Committee (DAC) Quality Standards for Development Evaluation, as well as related standards for evaluating development programming in fragile states.

The evaluation used three sources of information to build its lines of evidence: a review of literature and documentation (see Annex E); a program of structured individual and group interviews in Canada with development program and foreign affairs staff of DFATD and representatives of Canadian partner agencies; and, a three week field mission that included semi-structured interviews with a number of stakeholders.Footnote 5 Annex F provides a full list of people interviewed for this evaluation.

Assessment grids were completed for each sector and project in the sample, scoring performance against the evaluation criteria and indicators set out in the Evaluation Matrix. Annex B provides additional information on the methodological approach.

1.2.1 Project Sampling

From an inventory of 88 projects in the program portfolio, a purposive sampling approach was used to select 25 projects for more detailed review.Footnote 6 Three of those have been subject to project level evaluations. The sample focused on the three priority sectors for the program—justice sector reform, private sector development (PSD) and humanitarian assistance (HA).

The evaluation sample covered 64% of total program disbursements, including 45.7% of total HA disbursements; 98.1% for the justice sector; and 98.3% for the PSD sector. Four projects were chosen specifically to allow examination of alternative delivery models and approaches. Together, the sample projects represented a cross section of the project delivery modalities, mechanisms and channels employed by the program. Annex D lists the projects included in the evaluation sample.

1.3 Evaluation Limitations

The evaluators encountered delays in locating complete documentation and the unavailability of some local partner representatives during the field mission left information gaps that had to be filled by meeting alternate stakeholder representatives. In addition, the deteriorating security situation during the field mission precluded the planned visit to Gaza. While interviews with key contacts were achieved by internet-based communications, actual field visits in Gaza would have enabled on the ground verification.

Because the program is not working in a recognized country, many international institutions do not or have not gathered the same data on West Bank and Gaza as they do on other countries. For example, the World Bank’s annual Doing Business Review provided its first overall ranking for West Bank and Gaza only in 2013.

The performance measures set out in the program’s Performance Measurement Framework (PMF) for intermediate outcomes are directly linked to sector reporting. However, data on performance targets for all three priority sectors will not be collected until after the period covered by this evaluation.

Some targets remain undefined at the immediate outcome level of the PMF. For those that have been defined, the required reporting data has been inconsistently collected. Furthermore, the PMF for this program relies heavily on project level data collection systems of implementing partners. Due to often weak local capacityFootnote 7 and constraints imposed by the protracted crisis, continued insecurity and the complex situation on the ground, information is often limited to activity and output oriented reports, particularly for HA activities.

In the case of projects involving pooled funding, including the majority of HA projects with United Nations (UN) partners, baselines are prepared and reporting is done at an aggregate level that does not measure Canada’s contributions separately from those of other donors.

These limitations were mitigated by seeking alternative sources of data; placing an emphasis on ensuring soundness of the theory of change at program and project levels; and, triangulating the available data.

2.0 Context and Information on the Canadian Development Program

2.1 Context

The history of conflict and ongoing political instability has left a legacy of development needs and challenges in West Bank and Gaza. The 2007 split between Hamas and Fatah following the former’s legislative election victory in 2006 left a bifurcated system of governance, with Hamas controlling Gaza and Fatah governing in the West Bank. The Palestinian Legislative Council has not met since the split. Canada and most other donor countries consider Hamas to be a terrorist organization. Since the split, Canada has deemed the Fatah-supported Palestinian Authority (PA) as the preferred development partner.

Over the period of this evaluation, West Bank has remained relatively stable while Gaza went through two significant conflicts between Hamas and Israel, namely Operation Cast Lead in December 2008 to January 2009; and Operation Pillar of Defence in November 2012. The Middle East Peace Process was halted when the 2008 conflict began. After indirect talks between the parties, the process was restarted in 2010 by President Obama but direct talks once again ended shortly thereafter. Sporadic indirect talks took place up to the end of the evaluation period.

Palestinian law derives from several traditions that differ between Gaza and West Bank, including Egyptian law in Gaza, and Jordanian and British mandate law in West Bank, together with historical Ottoman laws, Israeli military orders and the Palestinian Basic Law passed in 2002. The result is lack of a harmonized legal framework. New laws are passed only by means of Presidential decree, an interim solution that may leave them subject to review by the Legislative Council or possibly expiry in the event the Legislative Council is not reconstituted sometime in the future.

In 2008, the Palestinian economy grew at a rate of 7.1% year over year and by 7.4% in 2009. The growth rate of the gross domestic product (GDP) in the West Bank and Gaza reached 11% on average in 2010 and 2011 (mainly due to donor-funded reconstruction and development activities), and then declined to 6.3% in 2012.Footnote 8 The Palestinian economy is one of the most dependent in the world on development assistance,Footnote 9 and the PA faces an ongoing fiscal deficit. As GDP growth has declined, so too has budgetary support from donors, which fell 12% below the requested level in 2012. Further, the PA is dependent on timely transfers of tax revenue, which belongs to the PA and is collected by Israel on their behalf under existing agreements with the Government of Israel. Regular transfers have been delayed or frozen at least three times between 2008 and 2012. In December 2012, they were suspended after the UN statehood vote and were reinstated in March 2013.

Within the context of an ongoing conflict and political instability, the PA faces serious external constraints that make it difficult to achieve the full potential of the area’s economy. Among these are limited control over Areas B and CFootnote 10 with their substantial land and water resources and where Palestinian businesses do not have access to development permits. Security related restrictions applied by Israel on movement of goods and people have limited the growth of the Palestinian economy and affected its competitiveness.

“Political uncertainty and Israeli security restrictions seriously impact the investment climate in the West Bank and Gaza.”Footnote 11 The amount of revenue collected by the PA from Gaza is low compared to expenditures there. The tax base in the West Bank also remains narrow due to inefficiencies in both policy and enforcement.Footnote 12 Other challenges include the growing decline in donor aid (an important driver of growth over the past decade) and sluggish growth of the world economy and the Israeli economy in particular.Footnote 13 These circumstances combine to make recovery from slow economic growth and high unemployment challenging, especially given global economic uncertainty.

The increasing population in West Bank and Gaza poses the greatest challenge for development programming in the face of economic stagnation. On the one hand, progress is being made on a number of social development indicators. Most of the indicators related to the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) for West Bank and Gaza have shown improvement over the past two decades, including:

- improving literacy rates during the period 1995 to 2012 from 78.6% to 93.6%;

- shrinking child mortality rates from 42.9 deaths per thousand births in 1990 to 22.6 in 2012; and,

- declining maternal mortality rates from 90 deaths per 100,000 live births in 1990 to 64 in 2010.Footnote 14

On the other hand, West Bank and Gaza still scored lower on the 2013 Human Development Index, when it was ranked 110th in the world, than in 2003 when it ranked 98th.Footnote 15 The main social issue is unemployment, which has exceeded 20% since 2001. In the first quarter of 2013, the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) reported unemployment in Gaza at 31%, compared to 20.3% in West Bank. Youth unemployment, reaching 41.1% overall in 2013, is a particular concern.Footnote 16 Despite improving educational achievement, work prospects for young people are dim, especially for women. Women comprise only 16% of the active labour force although they make up nearly 60% of tertiary education graduates.

In the face of the region’s economic challenges, poverty is also a major concern. Nearly 26% of Palestinians were identified as living in poverty in 2011 (by the PA definition) and half of this group was living in extreme poverty.Footnote 17 Food insecurity is a major issue, especially in Gaza; in 2011-2012, 70% of the 1.2 million registered refugees in Gaza depended on the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestinian Refugees (UNRWA) for food.Footnote 18

2.2 Canadian Development Program in West Bank and Gaza

Canada provided US $339.02 million in net aid disbursements between 2008 and 2013, making it the ninth-ranked OECD bilateral member donor. The United States is the largest, having contributed US $3,935.23 million during the same period.

| # | Donors | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | United States | 490.6 | 844.31 | 720.75 | 625.04 | 288.27 | 966.26 | 3935.23 |

| 2 | Germany | 77.38 | 98.67 | 104.58 | 124.06 | 136.74 | 117.38 | 658.81 |

| 3 | Norway | 115.78 | 100.14 | 109.51 | 112.12 | 107.2 | 107.49 | 652.24 |

| 4 | United Kingdom | 68.18 | 94.88 | 97.63 | 121.11 | 67.96 | 108.63 | 558.39 |

| 5 | France | 74.16 | 79.21 | 69.29 | 63.33 | 71.53 | 66.99 | 424.51 |

| 6 | Spain | 103.18 | 99.4 | 97.59 | 63.12 | 23.02 | 16.88 | 403.19 |

| 7 | Sweden | 71.81 | 66.88 | 58.51 | 64.27 | 62.77 | 61.02 | 385.26 |

| 8 | Japan | 30.3 | 76.69 | 78.55 | 74.83 | 73.05 | 50.06 | 383.48 |

| 9 | Canada | 44.28 | 41.2 | 65.05 | 77.71 | 60.4 | 50.38 | 339.02 |

| 10 | Netherlands | 75.14 | 46.22 | 35.66 | 53.79 | 31.91 | 20.22 | 262.94 |

| Total | 1150.81 | 1547.6 | 1437.12 | 1379.38 | 922.85 | 1565.31 | 8003.07 | |

*Data extracted on 17 Feb 2015 14:21 UTC (GMT) from OECD.Stat

** Total Net Aid Disbursements. Official Development Assistance (ODA) is defined as those flows to developing countries and multilateral institutions provided by official agencies, including state and local governments, or by their executive agencies, each transaction of which meets the following tests: i) it is administered with the promotion of the economic development and welfare of developing countries as its main objective; and ii) it is concessional in character and conveys a grant element of at least 25 per cent.

Canada has supported Palestinian refugees through contributions to UNRWA since 1950. In 1993, CIDA began augmenting this support through development assistance to West Bank and Gaza with programming in the areas of social development, governance, refugee and humanitarian assistance and peace building. According to the 2009-2014 Country Development Programming Framework, the greatest impact of these efforts was at the community level, working with civil society organizations.

The International Humanitarian Assistance (IHA) Directorate is responsible for managing humanitarian assistance programming in DFATD. However, in 2005 it was decided that humanitarian assistance for West Bank and Gaza should be delivered through the bilateral channel in order to generate more opportunities for program coherence in a complex, uncertain and unpredictable environment. An exception was made for the well-established relationship with the International Committee of the Red Cross and Red Crescent which continues to be managed by IHA. The bilateral program nonetheless consults IHA in the review and selection of humanitarian assistance projects.

Canadian development support to the PA was suspended after the election of Hamas in 2006 and all Canadian development assistance was redirected through UN humanitarian agencies, international NGOs and Canadian organizations. At the 2007 donor pledging conference in Paris that followed resumption of the peace talks through the Annapolis process, Canada made a multiyear commitment of CAD $300 million to West Bank and Gaza from 2008-2009 to 2012-2013. Of the total amount, $250 million was to be directed to development programming, with the balance committed to support security sector programming delivered through other Canadian Government departments, including the former Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade (mainly the Stabilization and Reconstruction Task Force - START), National Defence and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police.Footnote 19

As CIDA began to put the various parts of its Paris programming commitment in place, it undertook the preparation of the program’s first Country Development Programming Framework (CDPF). This document was published in December 2009 and covers the period 2009-2014. In 2009, West Bank and Gaza was identified as a program of focus for CIDA.

The general strategic direction set out for the program was articulated as:

“In line with Canadian foreign policy objectives, CIDA’s programming is intended to contribute to the creation of a viable, independent and democratic Palestinian state living side by side in peace and security with Israel as part of a comprehensive peace settlement” (Country Development Programming Framework, p.18).

Based on an analysis of opportunities and needs as well as the key elements of Canada’s foreign policy position with respect to the Middle East Peace Process, the Country Development Programming Framework identified three priority areas for development support: justice sector reform, private sector development (PSD) and humanitarian assistance (HA).

Humanitarian assistance programming would respond mainly to emergency needs, while the justice and PSD sector strategies were to focus on the institutions and processes that define a functioning state, in direct support of overall Canadian peace-building and regional security objectives related to a negotiated two-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

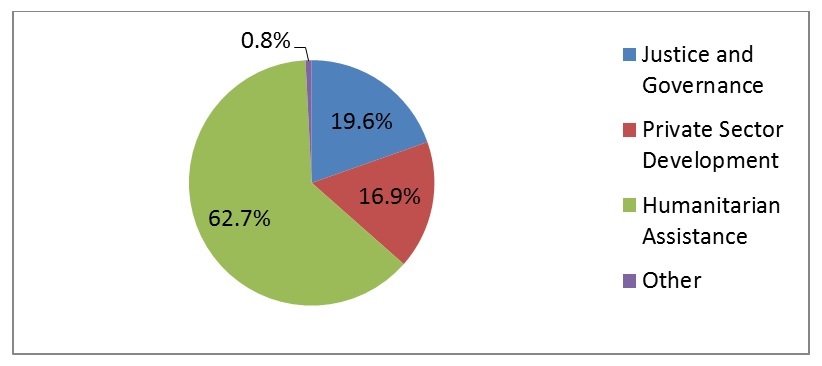

Figure 1. Total Disbursements by Priority Sector

Figure 1 - Text Alternative

Total Disbursements by Priority Sector

- Justice and Governance - 19.6%

- Private Sector Development - 16.9%

- Humanitarian Assistance - 62.7%

- Other - 0.8%

These priority areas fell within the overarching CIDA themes of Sustainable Economic Growth, Food Security, and Children and Youth. The 2009-2014 Country Development Programming Framework also emphasized a Whole-of-Agency and Whole-of-Government approach aimed at linking different program delivery channels with a view to managing the program for results, as well as forging links with other Canadian Government departments, particularly for security related programming.

Detailed sector and project level planning for the new program began in late 2008 based on the general parameters of the nascent Country Development Programming Framework. However, the long lead times required to develop institution-building programming and the need for flexibility to respond to the evolving realities on the ground, particularly in the face of the flare-up of conflict in the region, resulted in Canada’s development assistance being limited to HA for the initial part of the planning period, together with budgetary support provided through the World Bank Trust Fund.

3.0 Effectiveness

Finding: For both the shorter term humanitarian assistance activities and the much longer time frames necessary for effective institution building in justice and private sector development, the overall effectiveness of the program has been, with a small number of exceptions, satisfactory.

Finding: Overall, the program has made measurable contributions to strengthening the PA institutions that improve public perception of legitimacy of the legal system. It has improved the enabling environment for business, laying a strong foundation for further change. It has also contributed to meeting the needs of the most vulnerable through HA programming.

Finding: However, Canada has been ambitious in the justice and private sector development sectors in terms of both scope and time frame. It has fallen short of original expectations in some areas, but taking into account the particular challenges and risks inherent in this environment, is making progress toward achieving its intended objectives.

This section presents key findings for effectiveness in justice sector reform, private sector development and humanitarian assistance.

The West Bank and Gaza and Palestinian Refugees Program has sought to “strengthen the capacity and legitimacy of the PA institutions by increasing public confidence in the legal system, increase prosperity for Palestinian households and improve living conditions for vulnerable Palestinians” (Country Development Programming Framework, Section 3).

This succinctly frames the choice of institutional development as the programming focus in two of the three priority sectors: justice sector reform and PSD. It also conceptually links peace and security to improving conditions for the poor through humanitarian aid and economic growth.

3.1 Influence of Political and Security Constraints on Results

Against the backdrop of the stalled Middle East Peace Process, the fragile political and security environment in West Bank and Gaza has had direct impact on program management and delivery over the period of this evaluation.

Security concerns and border closings have limited access for planning and monitoring activities, especially relating to delivery of HA in Gaza. However, the international agencies through which HA programs are implemented have effective delivery systems and monitoring processes and were able to work around these constraints, except when active conflict has prevented access by any outside agencies.

The 2008 and 2012 conflicts in Gaza between Hamas and Israel resulted in loss of life and extensive damage to basic infrastructure, and affected delivery of HA. There has also been destruction of HA-funded infrastructure on many occasions outside these particular conflicts: for example damage to irrigation and water works, agricultural plots and livestock enclosures. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the UN, the level of loss is low enough that it is considered an acceptable cost of doing essential programming.

The impact of political and security constraints on private sector activities is also profound. While there have been slightly positive trends in investment in recent years, there remains little incentive for private sector investment in the Palestinian economy in the face of continuing political uncertainty and possibility of conflict. Closures of borders to movement of goods for security reasons and periodic withholding of transfer of tax revenues by Israel have disrupted the economy at unpredictable intervals.

The consensus view of representatives of leading private sector organizations, donors and the PA is that, while improvement is necessary, any progress in the enabling environment for business can only be minor in to the context of the overhanging influence of potential conflict and related security constraints. Expectations of development programs have to be tempered accordingly. Nonetheless, the World Bank and others have identified certain actions that are within the PA’s power to address.

The gains that have been made over the past five years in building justice sector capacities are vulnerable to any intensification of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, a worsening PA fiscal situation (also associated with the conflict), political challenges of reintegration of West Bank and Gaza and donor fatigue in a donor-dependent situation.

Structural issues also have delayed project implementation and constrained the ability to effect change. Most serious are the complex legal environment and the lack of a functioning legislative body. As noted in the discussion that follows on justice and PSD sector results, this has affected the PA’s ability to legislate change and in particular to rationalize the Palestinian Judicial Authority Law. This in turn limits the scope of change that can be realized in the institutional elements of the justice system. Projects in these two sectors have also seen delays in program delivery resulting from the frequent turnover of Ministers responsible for the partner PA Ministries. There was also in-depth due diligence analysis in some of Canada’s project approvals given the complex operating and decision-making environment in fragile and conflict-affected states. This in-depth analysis affected timelines for the UNRWA Food Aid programming in 2009, which in turn had an unintended impact on HA results, as described below.

Overall, the evaluation found that the relative stability between 2009 and 2012 in West Bank, where the justice and PSD activities were taking place together with some HA activities, allowed this programming to proceed as planned with minimal negative impacts on achievement of expected results.

3.2 Justice Sector Reform

The evaluation sample covered seven projects from DFATD’s governance/justice sector reform portfolio, representing 98.1% of total sector disbursements over the evaluation period. Three of these projects, accounting for most of the sector disbursements, were approved under the 2009-2014 Country Development Programming Framework (CDPF). These three projects collectively worked with all the key elements of the justice system, including system administration, prosecution services, the judicial and court systems and defence council services. They complemented DFATD’s non-development activities that have worked with police and public security forces on criminal investigation and the prison system. They also complemented activities of “legacy” projects that had been started prior to the new CDPF and that had a focus on human rights and civil society engagement with the justice system.

3.2.1 Justice Sector Challenges

There are many challenges to reforming the justice sector in the West Bank and Gaza, beginning with the complexity of its historical roots (see section 2.1). The existing Judicial Authority Law which, amongst other things, defines the roles and responsibilities of the sector’s three main institutions—the Ministry of Justice (MoJ), the Attorney General’s Office (AGO) and the High Judicial Council (HJC)—is outdated, leaving the mandates of PA justice actors, including the judicial and prosecutorial institutions, ill-defined.

Some steps have been taken to harmonize these different influences, at least in the West Bank (where the Fatah-controlled PA is dominant). However, the inability of the PA to properly legislate changes in law because the elected PA Legislative Council is not presently sitting makes broad-based judicial reform difficult.

The PA’s jurisdictional authority is also limited, partly as a result of the bifurcation of the West Bank and Gaza government in 2007 and partly because of the PA’s fragmented jurisdictional arrangements across Areas A, B and C in the West Bank. PA legal authority only extends—in part—to areas A and B, while Israeli military orders apply in Area C. Israeli law also applies to Israeli citizens throughout the West Bank. Given the political and security environment and the fragmentation of authorities, any perceived inconsistent application in the rule of law, particularly within the West Bank at the hands of either PA or Israeli authorities, serves to undermine trust in the rule of law. There are related internal structural impediments to the functioning of the justice system as well, especially the lack of decentralization in the delivery of justice which results in poor access outside the urban centres.Footnote 20

Until 2006, most of the Palestinian governmental justice institutions, including courthouses and forensics facilities, were located in Gaza. The political separation of the West Bank from Gaza in 2007 meant that the starting point for West Bank centered institutions was low and the justice sector badly in need of external assistance. This continues to be true, given the fragility of the PA’s fiscal situation and its high level of donor dependency.

3.2.2 Effectiveness of Justice Sector Programming

Finding: Justice sector programming was found to have achieved satisfactory results. Evidence shows improved capacity and functioning of rule of law institutions, especially the Ministry of Justice and Attorney General’s Office. Legacy projects continue to provide access to rights-based social services and networking of civil society around peace building efforts.

Finding: However, effectiveness was lower in two projects. The Courthouse Construction project has been delayed and will not meet its original target of three new court houses. As well, the Forensic Human Resources and Governance project was significantly behind schedule at the time of this evaluation.

The intermediate outcome expected of justice sector programming is “more transparent, equitable and predictable justice system institutions that apply the rule of law and uphold human rights for men, women and children”. As data is not yet being collected on all indicators for this expected result, the evaluation consulted a household survey of public perceptions of Palestinian justice and security institutions conducted in 2011-2012 by the Rule of Law and Access to Justice project as a surrogate means of measuring progress. The overwhelming majority of respondents view these institutions as legitimate and choose to use them to resolve all manner of disputes.

The survey results indicate that 91% of respondents call the police when in danger; 71% considered that courts are the only legitimate institutions through which to resolve disputes; and 37.7% were satisfied that the public prosecution maintains dignity and human freedom.Footnote 21 This survey does not have an earlier point of comparison; however, it does show a reasonably high level of confidence in what the survey calls the “technical competence” of PA justice institutions at the time of the survey, approximately two years after the start of new CIDA projects in this field. While no direct link to CIDA programming or attribution can be made, there are few other donors working in this field as comprehensively as CIDA has done.

The evaluation also considered aggregate performance of sample projects as a measure of program performance. Five of the seven sample projects were considered satisfactory or fully satisfactory in terms of achievement of their intended results, including all three of the responsive projects in the portfolio (as noted in Table 2). The results achieved by these five projects are summarized below.

| Project | Status | Immediate Outcomes Expected | Results Achieved |

| Networking for Peace | Legacy |

|

|

| McGill Middle East Program in Civil Society and Peace Building II (MMEP II) (responsive) | Legacy |

|

|

| Judicial Independence and Human Dignity (Karamah) | Legacy |

|

|

| Support to Public Prosecution Services (Sharaka) (responsive) | CDPF generated |

|

|

| UNDP Rule of Law-Access to Justice (responsive) | CDPF-generated |

|

|

The assessment of results achievement for two of the above-mentioned five projects requires some qualification. First, while this evaluation found the UNDP Rule of Law program to have been a successful project, DFATD’s funding was directed away from those components aimed at providing access to justice services for vulnerable people.Footnote 22 These activities were supported by other donors; therefore DFATD cannot claim attribution for the program’s considerable successes in those components.Footnote 23

Second, although the Karamah project made progress in creating a judge-centred judicial education model based on human rights principles, it faced several challenges affecting sustainability. The project received inconsistent levels of support from the High Judicial Council (HJC) and the PA suspended operations of its main training partner, the Palestinian Judicial Institute. Nonetheless, the project has brought about changes in attitudes of individual project participants (judges) and in judicial education and practice that are sustained by ongoing partnerships between the universities involved and by champions of the new model within the HJC.

Two other projects, both central to DFATD’s justice sector portfolio, faced serious challenges:

- Courthouse Construction. The objective of this project was to increase the availability of safe and well-managed courthouses in the West Bank. It originally provided for the design, construction and equipping of three courthouses in Ramallah, Hebron and Tulkarem by March 2014. The Ramallah courthouse was subsequently removed as the project budget was re-scoped to address the two, higher priority, regional courthouses. At the time of the evaluation field visit, the scope of the remaining courthouses was under further review and progress had been suspended pending the approval of a revised project budget and design parameters.

- Forensic HR and Governance. At the time of the evaluation, this project was ready to commission a temporary lab facility, seven months behind schedule. Also behind schedule were the project’s various human resource development activities, for which the assessment of needs took much longer than originally anticipated.

The evaluation pinpointed a number of underlying causes for the problems being experienced in implementation of these two projects, including:

- Flawed initial estimation of space requirements, timelines and costs (for the Courthouse Construction project);

- A lack of CIDA expertise in infrastructure development or recent experience in construction management, which is required to prepare terms of reference to contract executing agencies, managers and monitors for construction projects and to review design and cost estimates;

- Weak project management at the beginning of both projects. The UNDP project manager for the Hebron Courthouse and the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) project manager for the Forensic HR and Governance project were both replaced;

- Inadequate critical path scheduling and implementation by the executing agency (Forensic HR and Governance);

- Delayed contracting of a project monitor for the Forensic HR and Governance project;

- The timing of decision-making, particularly with regard to the Courthouse Construction project re-scoping;

- Delays in sub-contracting and/or procurement actions by the executing agency (Forensic HR and Governance); and

- The lack of congruence between UNODC and DFATD results-based management systems (Forensic HR and Governance).

While a number of these problems were due to shortcomings in the efforts of implementing agencies, there was also a need for more timely decision-making by DFATD (for example, in the Courthouse Construction project re-scoping). Field interviews revealed that problems with the Forensic HR and Governance project are having a detrimental impact on the relationship between DFATD and its two PA partners, the Ministry of Justice and the Ministry of Interior, due to dissatisfaction with the progress made by the executing agency. The failure to deliver on the full original commitment of three courthouses will reduce the scope of the achievement of that project’s planned result of increased availability of safe and well-managed courthouses in the West Bank.

3.3 Private Sector Development

The PSD sample examined for this evaluation consisted of five projects and covered 98.3% of disbursements in this sector. Canada’s activities took two distinct forms. In the first years of the evaluation period, along with a number of other donors, the program provided budgetary support to the PA through a World Bank Trust Fund. After approval of the 2009 CDPF, the program put into place three “flagship” projectsFootnote 24 that engaged nearly all key institutional players in the Palestinian economy in the public and private sectors, including the Ministry of National Economy (MoNE), and many of the apex private sector organizations in the West Bank. These same institutions also partner with other donors on specific projects but the CIDA strategy of focusing fully on institutional support was unique among donors.

3.3.1 PSD Sector Challenges

Many influences on the economy are outside the control of the PA, starting with security restrictions on access by Palestinians to Area C and East Jerusalem. The West Bank is landlocked and unable to move goods without going through Israeli-controlled border crossings. Poor processes of documentation make borders porous to low quality/low cost imports that evade PA import tax regulations and supplant locally manufactured products in the marketplace. Overall, exports and imports are subject to changing political and security circumstances.

Domestic and foreign investment is low due to the uncertainties caused by the ongoing Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The political separation of Gaza from West Bank and security restrictions imposed on movement of people and goods in and out of Gaza have reduced potential benefits of economies of scale in production and related enterprise opportunities. The labour market and, to a certain extent, economic activity as a whole remains linked to the large number of informal, mainly family-owned microenterprises (those employing five people or fewer).Footnote 25

Sustainable economic growth is a growing priority for the donor community at large and, as noted in section 7.1, is an area that is not well coordinated within the donor community. Canada is one of many contributors in the PSD sector, working with entities that also receive support from other donors. Despite the program’s unique focus on institution building, specific attribution of results is sometimes difficult.

For CIDA, the PSD sector presented challenges that made the choice to pursue an institutional strengthening focus risky, although it responded to a significant need. The starting point was characterized by weak and poorly coordinated public and private sector institutions, and the objectives of the program were complex and ambitious. In addition, institutional change is widely recognized in development literature to require long-term commitment and take a long time to manifest results.Footnote 26

The Country Development Programming Framework was approved in December 2009, and the three “flagship” PSD projects were approved in March 2011. For purposes of this evaluation, this leaves only two years of implementation, insufficient to assess the full impact of these collective interventions. There were delays in the early stages of the three projects, caused by issues such as partners’ limited understanding of their roles and responsibilities; difficulties in relations between the PA and implementing partners; and generally poor understanding of DFATD’s requirements for project planning and reporting.

By the end of the evaluation period, these issues had been resolved or were being addressed. However, delays in project start-up mean that data on immediate outcomes is very limited, and no information is available on longer term results.

3.3.2 Effectiveness of PSD Sector Programming

Finding: PSD sector programming was found to have achieved some satisfactory results. There is evidence of increased capacity of Palestinian private sector organizations as well as positive regulatory changes that will improve business efficiency. However, it is too early to assess whether all intended results will be fully achieved.

The expected immediate outcomes set out for the PSD sector are: increased responsiveness of the policy and regulatory framework for micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) and increased access to local and international markets for Palestinian firms, including those owned by women. These support the intermediate outcome of creating a more investment-favourable business environment for Palestinian firms, including those owned by women.

Results indicators for the PSD sector at the immediate outcome and output levels are not clearly defined and depend heavily on reporting by the three “flagship” projects specifically developed under the 2009-2014 Country Development Programming Framework, supplemented by data to be collected by the program. Collection of this data has so far taken place for some but not all indicators. This evaluation therefore relied on other sources of information to provide evidence of progress toward achievement of intended objectives. The World Bank Doing Business (DB) indicator of “number of days to start a business” was adopted in the CIDA PMF and has seen a marginal improvement from 49 days in 2010 to 45 days in 2014.Footnote 27

The World Bank’s Interim Strategy Note for West Bank and Gaza 2012-2014 states that “The 2012 Doing Business Indicators of the Bank do not reflect improvement of the business environment”.Footnote 28 It goes on to identify certain changes, some introduced through DFATD-supported projects,Footnote 29 which the World Bank expects to be reflected in improved scores but whose impacts had not yet been identified. In fact, the overall Doing Business ranking for West Bank and Gaza improved from 145 in the 2013 report to 138 in the 2014 report, thanks mainly to elimination of a minimum requirement for paid in capital in start-ups. The other nine Doing Business component indicators remained more or less stagnant, with the “Trading Across Borders” indicator even showing a slight decline. This indicates that there are a number of areas in which PSD sector programming is active that could see further improvement as the “flagship” projects continue to be implemented.

Palestinian statistics on foreign direct investment in West Bank and Gaza and import/export data also show a slow but positive trend over the period from 2010 to 2012. These figures are short term and subject to a range of influences, only one part of which may be attributed to donor (and in particular DFATD) contributions in the PSD sector. However, they are positive trends during a period of relative stability, showing decreasing foreign investment by Palestinian investors and increasing local investment in businesses. Among other things, this may reflect increased confidence in the overall business environment, to which DFATD has contributed along with other donors.

Another point of comparison is the documented capacity of partners at the start of the Country Development Programming Framework cycle. CIDA’s 2009 PSD sector planning study noted:

“…private sector associations…admitted to lacking technical capabilities to understand the legal language of various laws... Accordingly, private sector input and effectiveness in influencing economic policy has been minimal, resulting in legislation that often seems to conflict with private sector needs.”Footnote 30

The evident need for institutional strengthening and reform applied equally to the public and private sector institutions engaged in the economy. The same study noted that the Ministry of National Economy (MoNE) had “admitted its lack of capacity to implement its mandate and develop policies and procedures, promote trade and modernize industry as well as serve both producers and consumers” (p.47).

The main private sector organizations in West Bank and Gaza were functioning at various levels but “many of these institutions remain ineffective in their efforts to influence economic policy and legislation” (p.46). The key Palestinian partner in the Regional Economic Empowerment of Women Project (REEWP), the Palestinian Businesswomen’s Association (ASALA), was limited to providing small loans to women micro-entrepreneurs and lacked advocacy or business development support capabilities.

“The CIDA project has enabled a foundation of skills and capacities [in PalTrade] to be used in other strategic priorities, beginning with a central role in the formulation and eventual implementation of the National Export Strategy.”

There are many illustrations of the program’s measurable progress over the evaluation period in addressing this widespread weakness in capacity. The work of the Federation of Palestinian Chamber of Commerce, Industry and Agriculture (FPCCIA) of coordinating and preparing a private sector position paper in 2012 on amendments to the Labour Law is one example. Chamber of Commerce representatives interviewed for the evaluation claimed that “No-one else has that capacity” for analysis and advocacy that the Federation has now developed with the support of the Improved Framework Conditions for Palestinian Businesses project.

The Palestinian Trade Centre (PalTrade) attributes its designation as a representative interlocutor with the PA for Palestinian business on trade matters at least partly to DFATD programming support. The organization also has been mandated, with €3 million direct European Union (EU) funding, to lead the preparation of the PA’s National Export Strategy, a clear reflection of PA and EU confidence in PalTrade’s technical and management capacity to carry out this important task.

The Palestinian Federation of Industry has also experienced a revival with the support of the Framework Conditions project, from being what one interviewee described as “nearly defunct” in early 2012 (a view confirmed by other interviewees) to being actively involved in policy and advocacy, as well as revamping its Industrial Modernization Centre to provide technical support to Palestinian industry.

There were direct governance achievements from the PRDP Trust Fund as a result of the PA’s access to core budgetary support for delivery of services to Palestinians. A clear example is the improvement documented by the World Bank in the social safety nets for poor Palestinians. There were also public financial management improvements resulting from Trust Fund performance conditionality requiring reform in budgeting, control of finances, external auditing, staff reform and other aspects of governance. In its April 13, 2011, Staff Report for the Meeting of the Ad Hoc Liaison Committee, the International Monetary Fund concluded that “the PA is now able to conduct the sound economic policies expected of a future well-governed Palestinian state, given its solid track record in reforms and institution-building in the public finance and financial areas” (p.3).

ASALA, the Palestinian partner for the REEWP project, also made substantial progress in building its capacity. ASALA admitted that, at the start of the project, it “had no idea or experience at all in advocacy skills, strategies and competencies”. ASALA has now negotiated a Memorandum of Understanding with the Federation of Chambers of Commerce for special registration rates for microbusinesses that has benefitted all micro-entrepreneurs, not just women, and has significantly increased Chamber membership in this category. By the end of 2013, ASALA was close to establishing an independent commercial microcredit institution that will provide a major source of income for the NGO’s ongoing services to small and household level businesswomen. ASALA is now actively supporting and encouraging women to move into the formal sector by registering their businesses in order to take advantage of services offered through the Ministry of National Economy (MoNE) and local Chambers.

Despite this range of achievements, not all the intended PSD results have been realized, sometimes as a result of project level issues or decisions, and sometimes for reasons beyond the control of the projects themselves. For example:

- Public-Private dialogue (Framework Conditions project) is still not taking place to the satisfaction of the business community or in a manner that has produced substantive change in policy. The meetings that have taken place have been assessed by different participants as having fallen short in the hoped-for degree of engagement by MoNE;

- Gender units have been established in some organizations but have not really been integrated into ongoing operations or had an effect on policy developed by these organizations;

- Functioning of MoNE’s policy unit was assessed by an independent analyst in 2013 as having had “disappointing results so far”, mainly attributed to the internal political environment;

- The Palestinian Shippers Council made the decision to contract out research as required instead of creating a research unit as originally planned; in addition, at the time of the evaluation field visit, it had been slow in developing training materials and products.

At the time of the evaluation field mission, these issues were known to the program and to implementing partners, and steps were being taken to address shortfalls to the extent possible. By the end of the evaluation period, there was a mixed record of progress in PSD sector projects and the evidence, including assessments by other analysts, indicates that more time and effort is needed to realize the intended intermediate outcomes.

3.4 Humanitarian Assistance

The greatest proportion of Canadian assistance to West Bank and Gaza over the evaluation period is classified as emergency or humanitarian assistance. HA programming comprised half the projects implemented—44 of 88—and $171 million, or 63% of total disbursements made by the program.

A sample of ten emergency assistance projects worth $78 million, managed by the bilateral program, was assessed. All of them were responsive projects and all but one used the “multi-bi” mechanism.Footnote 31 They cover all major HA partner agencies over the five years being evaluated and close to 46% of total HA disbursements. As Canada worked with the same partners year after year, key respondents like CARE, FAO, UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), UNICEF, UNRWA and WFP reported in interviews about their ongoing relationship with Canada rather than about any single year of funding. Thus, the sample covered ongoing relationships with partners who between them managed 92% of total Canadian HA in West Bank and Gaza during the period being evaluated.

All HA programming in West Bank and Gaza reviewed for this evaluationFootnote 32 responded to the UN annual Consolidated Appeals Process (CAP) and UNRWA appeals.Footnote 33 The CAP focused on harmonizing and coordinating large-scale, sustained humanitarian action, efficient and effective lifesaving and protection and promotion of livelihoods. The PA was consulted in all CAPs, which align with Palestinian plans and priorities.

DFATD HA funding supported activities including immediate relief, emergency preparedness and early recovery. In the period 2008-2009 to 2012-2013, the largest share of Canada’s humanitarian funding in the West Bank and Gaza supported food security, and this concentration increased during the period.

3.4.1 Humanitarian Assistance Challenges

Over the evaluation period, humanitarian needs in West Bank and Gaza changed very little and were characterized by “entrenched levels of food insecurity, limited access of vulnerable Palestinian communities to essential services and serious protection and human rights issues.”Footnote 34 HA provided from all donors (including CIDA/DFATD) through the CAP has targeted the poor, including a large portion of the non-refugee population of West Bank and Gaza who live in poverty, mainly due to the ongoing conflict, and Palestinian refugees and their descendants.

Documentation and key respondent interviews with other donors and humanitarian agencies revealed that donors have begun to question whether short-term humanitarian solutions are appropriate in the West Bank and Gaza, in a situation of long-term conflict. There is growing recognition that HA addresses only a portion of the needs in the West Bank and Gaza and will never be sufficient. Meeting these needs requires longer term political solutions and a resolution of the underlying political conflict.

As a result, the Consolidated Appeal for 2012-2013 adopted a two-year strategy for the humanitarian community and the UN launched its planning process for a Development Assistance Framework (UNDAF) for the West Bank and Gaza in December of 2012. This approach has continued after the evaluation period. Near the end of 2013, the UN released a Humanitarian Programme Cycle containing a three-year Country Strategy for the period of 2014-2017, which focused on tackling food insecurity and improving the protection environment for Palestinian communities most at risk.Footnote 35

Humanitarian agencies like CARE, UNICEF and WFP noted that in the face of the global financial crisis, donor funding was constrained and there was a move towards needs-based assistance that targets only the most vulnerable, including those with refugee status. Insufficient focus and/or targeting of humanitarian assistance might be contributing to aid dependency and working against state building. This needs-based approach has been adopted by the PA’s Ministry of Social Affairs (MoSA), which is working with the UN agencies on developing a Palestinian system for distribution of social assistance programming.

3.4.2 Effectiveness of HA Programming

Finding: Humanitarian assistance programming met or exceeded planned short-term results, with one exception where the timing surrounding project due diligence and approval affected the attainment of results.

Finding: The Principles of Good Humanitarian Donorship have been largely respected, although in one of the sample projects a late funding decision affected results, and in two either unexpected or unexplained funding decisions led those recipients to question predictability.

Given that six of the ten projects reviewed for the HA portfolio had a planned duration of only one year, project documentation concentrated on activities and outputs.Footnote 36 Based on a rollup of the ten sample projects over the period of the evaluation, the projects achieved their output targets as specified in the program level Performance Measurement Framework. Indicative results against these targets include:

- Food distributed to over 500,000 targeted food insecure and vulnerable households (target—347,000 individuals);

- Food vouchers (or conditional cash transfers) distributed to almost 200,000 targeted food insecure and vulnerable households (target—98,000 households);

- School snacks or meals distributed to over 450,000 school children in targeted schools in food insecure areas (target—80,000 children);

- Water infrastructure improvements provided to about 330 male and female farmers (target—100 households);

- Training sessions on agricultural techniques and management practices provided to 3,350 targeted male and female farmers (target—4,000 households);

- Animal health inputs and veterinary services provided to about 1,200 targeted farmers and producers (target—800 breeders and 500 households).

The program PMF targets results at the ultimate outcome level by 2024, but results are expected at the intermediate and immediate outcome levels by 2014. Thus, by the end of the programming period some results should start to become apparent, and in fact the evaluation found evidence of progress. Indicators for both intermediate outcomes (household expenditure on food and percentage of food insecure households) are moving in a positive direction from the baselines.

However, a review of the available sources, such as the Socio-Economic and Food Security Survey 2012, does not show an improving trend in humanitarian conditions for immediate outcomes, especially access to nutritious food, largely due to the continuing lack of progress on a political solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. While this appears to confirm the need for longer term solutions and an increased focus on building resilience, it is important to note that in many cases it is too early for a rigorous analysis of trends as we have only one or two years of data. As the crisis ebbs and flows, the year chosen for the baseline can have an impact as well.

Effectiveness can also be assessed in relation to broad expectations of humanitarian assistance programming. At the departmental level, West Bank and Gaza HA programming is expected to respect CIDA’s Guidelines for Emergency Humanitarian Assistance which states that the expected outcome of HA is “helping meet the basic human needs of conflict and natural disaster affected communities”. The program level outcomes are: improved or maintained health; improved physical security; and, improved or maintained household and community livelihoods.Footnote 37