Evaluation of the Canada Fund for Local Initiatives - Final Report

Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada

Office of the Inspector General

Evaluation Division

May 2016

Table of Contents

- Abbreviations, Acronyms and Symbols

- Acknowledgements

- Executive Summary

- 1.0 Introduction

- 2.0 Evaluation Scope & Objectives

- 3.0 Operational Considerations

- 4.0 Strategic Linkages

- 5.0 Evaluation Approach & Methodology

- 6.0 Limitations to Methodology

- 7.0 Evaluation Findings

- 7.1 Relevance Issue 1: Continued Need for the Program

- 7.2 Relevance Issue 2: Alignment with Government Priorities

- 7.3 Relevance Issue 3: Consistency with Federal Roles & Responsibilities

- 7.4 Performance Issue 4: Achievement of Expected Outcomes

- 7.5 Performance Issue 5: Demonstration of Efficiency & Economy

- 8.0 Conclusions of the Evaluation

- 9.0 Recommendations

- 10.0 Management Response And Action Plan

- Appendix 1: List of Findings

- Appendix 2: List of Tables and Figures

Abbreviations, Acronyms and Symbols

- ACCTCB

- Anti-Crime and Counter-Terrorism Capacity Building

- CA

- Contribution Agreement

- CBP

- Capacity Building Programs

- CFLI

- Canada Fund for Local Initiatives

- CIDA

- Canadian International Development Agency

- CTCBP

- Counter-Terrorism Capacity Building Program

- DFAIT

- Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade

- DFATD

- Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development

- FPDS

- Foreign Policy and Diplomatic Services

- HOM

- Head of Mission

- GPP

- Global Partnership Program

- GPSF

- Global Peace and Security Fund

- GoC

- Government of Canada

- IAE

- International Assistance Enveloppe

- ICP

- Investment Cooperation Program

- IRC

- Deployment and Coordination Division

- IRH

- Human Affairs and Disaster Response Division

- MENA

- Middle East North Africa

- MCO

- Management Consular Officer

- MOU

- Memorandum of Understanding

- NGO

- Non-governmental organisation

- ODA

- Official Development Assistance

- ODAAA

- Official Development Assistance Accountability Act

- ORF

- Office for Religious Freedom

- PAA

- Program alignment architecture

- RFF

- Religious Freedom Fund

- SFMC

- Centre of Expertise for Grants and Contributions

- UN

- United Nations

Acknowledgements

The evaluation team would like to express its appreciation to the CFLI team at IRC, CFLI program managers, CFLI representatives and recipients, Headquarter participants and members of the Evaluation Advisory Committee for their participation during this evaluation.

Executive Summary

The CFLI is a contribution program in over 100 countries that is delivered by Canada’s missions abroad. Through the CFLI, Canadian missions fund local projects that are modest, local, and short-term, which are aligned with the Government of Canada’s foreign policy objectives. The CFLI also provides immediate assistance in disasters or emergencies. The CFLI, previously administered by the former Canadian International Development Agency, is also required to be aligned with at least one of five International Assistance Envelope themes.

The Deployment and Coordination Division (IRC) at DFATD, in particular the Canada Fund Unit, established the strategic direction and training protocols for the CFLI. In the event of natural disasters or humanitarian emergency, DFATD’s Humanitarian Affairs and Disaster Response Division (IRH) is the lead for endorsing CFLI funding. This ensures a coordinated and coherent response that is consistent with Canada’s international legal obligations and policy approaches.

The reference period for this evaluation covers two complete programming cycles, 2012-13 and 2013-14, since the transfer of CFLI from ex-CIDA to DFATD. Over the last two programming cycles, the average dollar amount of CFLI projects has remained relatively unchanged. In 2013-14, the average dollar amount was $23,938 (based on a total of 292 contribution agreements signed), slightly higher than in the previous year, 2012-13, at an average of $22,585 based on 615 funded projects. Most CFLI funding supports local civil society organizations and related local institutions. CFLI projects also supplemented and complemented other DFATD programs such as the Religious Freedom Fund (RFF).

The goal of this evaluation was to provide DFATD's senior management with a neutral and evidence-based assessment of the relevance and performance of the CFLI since its transfer to former DFAIT in 2012 until 2013-14. The CFLI evaluation adopted a mixed-methods approach combining primarily qualitative information from various sources with some qualitative and quantitative data obtained from project files and surveys of Heads of Missions, CFLI program managers, and CFLI recipients. The evaluation reviewed 30 annual mission reports and interviewed 34 key informants. Survey response rates were relatively high (60% for HOMs, 78% for CFLI program managers). Of 200 surveys distributed to recipients of CFLI funding, 39% were completed. The evaluation was unable to access all program recipients given language barriers and unreliable internet access.

Key Findings

The CFLI was found to be useful for missions to further the foreign policy objectives of Canada, especially in the absence of bilateral programs. It is further seen as effective for developing networks, especially within civil society. The CFLI is unique because it responds to local needs while also supporting Canada’s foreign policy priorities. However, some key informants expressed a desire for the time when the CFLI was solely oriented towards development. Almost all informants were concerned over the sustainability of the program and its impact on relationships with civil society in the face of diminishing funding.

The CFLI was useful for rapid response to assist local communities when facing emergencies and disasters, but its impact was constrained relative to its budget. Although its small size and limited funding inhibited the ability to build sustained capacity, the CFLI did respond to immediate needs in priority countries.

Further, during the reference period, the program direction for the CFLI was shifted to more pronounced priorities under the International Assistance Envelope (IAE). The evaluation found that this change in program direction has aligned CFLI with foreign policy objectives within the IAE thematic priorities of advancing democracy, security and stability noted in 2013-2014. The shift has raised certain issues about the intended objectives of the CFLI and its alignment with the PAA, while at the same time, acknowledging the contribution of CFLI in the promotion of Canadian values.

With regards to roles and responsibilities, DFATD and IRC are considered appropriate for the management of the CFLI. Most respondents were impressed and satisfied with the work of IRC. Roles and responsibilities were clearly understood and accepted by most stakeholders.

Despite limited resources, the CFLI was found to contribute to heightened awareness of Canadian values amongst local stakeholders as well as increased visibility of Canadian priorities and interests. In particular, Canada’s values gained significant awareness with first-time recipients of the CFLI and enhanced Canada’s reputation of being able to connect with civil society supplementing other countries activities by creating and seizing opportunities to further advance those values in other intergovernmental contexts.

The CFLI increased Canada’s access to decision makers in local communities in other countries. Further, the CFLI increased access to local stakeholders to information, facilities, and tools in order to advance security, stability, and political-economic sustainability in their communities. The CFLI has had moderately positive effects on strengthened bilateral relations and was generally effective on issues of democratic transition and protection of human rights more than on economic governance.

The CFLI contributed moderately to build the capacity of local communities or organizations to respond to emergencies and natural disasters in about 25% of initiatives. This result demonstrated the added value of the CFLI in reaching beyond its intended objectives. Although few cases were found to have built resilience in communities, the CFLI was not designed to provide long-term or sustained support for communities to develop such capacity but yet, the CFLI funds provided quick response to assist local organizations to participate in critical emergencies. Evidence of this support was found in projects that provided immediate medical relief to protestors during the Ukrainian crisis, for example.

Finally, the CFLI complemented other DFATD programming. The CFLI had a greater impact in smaller countries especially in the absence of, or discontinuation of bilateral programs. All participants in this evaluation voiced strong concerns over the impact of delayed program allocations and diminished funding on the delivery of the CFLI. Programming, over the last two cycles, was compressed to half the time of a regular 12 month programming cycle, for which key informants raised concern over the negative impact of losing the value of the CFLI to advocate and promote Canadian interests.

Recommendations

Recommendation #1: It is recommended that DFATD bring greater clarity to the CFLI’s program direction on its alignment with various departmental objectives, priorities and ODAAA requirements.

Recommendation #2: It is recommended that DFATD take measures to improve the timeliness, predictability and sustainability of funding allocations to optimize operational efficiency.

1.0 Introduction

The Evaluation Division (ZIE) at the DFATD is mandated by Treasury Board Secretariat (TBS) through its Policy on Evaluation (effective April, 2009) to conduct evaluations of all direct program spending of the Department, including Grants & Contributions programs. ZIE evaluation reports are tabled for approval to the Departmental Evaluation Committee (DEC) chaired by the Deputy Ministers and the Associate Deputy Minister of the Department.

The Evaluation of the CFLI was included in the approved Five-Year Evaluation Plan of the Department. Consistent with the TBS Policy, the purpose of this evaluation was to assess the relevance and performance of the CFLI and identify lessons learned regarding the efficiency, effectiveness and economy of its delivery. The target audiences for this evaluation are the Government of Canada (GoC), DFATD's Senior Management and the Canadian public.

1.1 Background and Context

The CFLI is a contribution program that is delivered through Canada's missions abroad in over 100 countries. During the evaluation reference period, 2012-13 to 2013-14, the CFLI was delivered in over 130 countries, through 69 missions. The CFLI funding is intended for modest, local and short-term initiatives which allow Canadian missions to fund local projects that are aligned with the GoC's foreign policy objectives. CFLI funds are also used to provide immediate targeted Canadian assistance, at the local level, to emergencies and natural disasters. All CFLI projects must be compliant with Official Development Assistance (ODA) requirements.

1.2 Program Objectives

The CFLI program has two main objectives:

- 1. To contribute to the achievement of Canada's thematic priorities for international assistance with a particular focus on advancing democracy and ensuring security and stability; and,

- 2. To assist in the advocacy of Canada's values and interests and the strengthening of Canada's bilateral relations with foreign countries and their civil societies.

It should also be noted that in exceptional circumstances, the CFLI can also be used to provide rapid and small-scale responses to humanitarian situations.

The CFLI is funded from the International Assistance Envelope (IAE) and is reported as Official Development Assistance. Projects must fall within the five IAE themes (with particular focus on the two last themes):

- 1. Sustainable economic growth;

- 2. Increasing food security;

- 3. Children and youth;

- 4. Advancing democracy; and

- 5. Security and stability.

CFLI projects should also be considerate of the IAE’s three cross-cutting themes that include: gender equality, environmental sustainability and governance.

The requirement to align with one of these priorities was consistent with historic practices when the CFLI was administered by the former Canadian International Development Agency. Following the transfer of the CFLI to the former DFAIT, missions were expected to orient programming more towards the last two priorities (advancing democracy and, security and stability). In 2013-14, CFLI programming was to be aligned with strategic themes as approved by the Minister of Foreign Affairs.

According to the Department's Program Alignment Architecture (PAA), in 2013-14, the CFLI outcomes were to be aligned with and intended to contribute to the Diplomacy and Advocacy program activity, under DFATD's Strategic Outcome # 1: "The international agenda is shaped to Canada's benefit and advantage in accordance with Canadian interests and values."Footnote 1 The evaluation addressed the nature and extent of progress to date on achieving the following outcomes.

Long-Term Outcomes:

- Over the long term, CFLI programming is expected to contribute to improving Canada's bilateral relations with recipient countries and their civil societies through development and advocacy activities carried out in partnership with a broad range of local actors, or through support to local responses to natural disasters and emergencies.

Intermediate Outcomes: The anticipated results of the CFLI in the medium term include:

- Improving Canada's networks with civil society actors and the ability to influence local decision makers;

- Building visibility for the missions in order to better promote Canadian priorities and interests in the country/region; and,

- Strengthening the capacity of local communities to respond to natural disasters and emergencies.

Immediate Outcomes: Immediate outcomes for the CFLI include:

- Increased awareness among local stakeholders of Canadian values of democracy, security and stability;

- Increased access by local stakeholders to information, facilities and/or tools needed to support both security and stability efforts as well as local political-economic sustainability;

- Increased access by Canadians to key decision makers; and,

- Increased capacity to support humanitarian assistance efforts within communities affected by natural disasters and emergencies.

The CFLI funds a large number of projects. As a result, outputs are project-specific (i.e. direct products or services offered). The outputs selected for each funded CFLI project are described in their respective contribution agreements. These outputs must be reported on by funding recipients in their final report to the mission and by the mission in the end-of-project report submitted to DFATD-IRC.

1.3 Governance

Under the former CIDA, the CFLI was managed in a decentralized manner as an element of country programming. Since its transfer to the former DFAIT, now DFATD, the CFLI has been established as its own program with a new governance structure, accountability and oversight framework. The CFLI is managed by the Deployment and Coordination Division (IRC) at DFATD with responsibilities assigned to Heads of Mission (HOM) and mission staff. In addition, the CFLI Unit at IRC establishes the strategic direction and develops training protocols for mission staff in an effort to ensure that CFLI approaches to programming are consistent across missions and regions.

The CFLI Unit has a number of responsibilities, including but not limited to:

- serving as the point of contact at HQ for missions and departmental staff seeking guidance on issues pertaining to the CFLI;

- maintaining the policy and administrative framework for CFLI management at missions;

- ensuring that the CFLI is integrated into missions' annual strategic plan;

- arranging and delivering training for mission and HQ staff (e.g. training on the management of the CFLI as a part of Foreign Policy and Diplomacy Services (FPDS) pre-departure training);

- reviewing, analysing, and consolidating CFLI performance reports from missions and preparing consolidated reports for DFATD senior management and for external reporting purposes;

- producing communications materials on the CFLI;

- recommending annual CFLI budget allocations to missions (as well as mid-year budget adjustments) in consultation with geographic Director-Generals; and,

- coordinating the approval of mission-specific Vote 10 (grants and contributions) allocations and the approval of CFLI strategic themes.

In the event of natural disasters or humanitarian emergencies, DFATD's Humanitarian Affairs and Disaster Response Division (IRH) is the lead in endorsing CFLI funding. This ensures a coordinated and coherent response that is consistent with Canada’s international legal obligations and policy approaches. Missions are responsible to manage CFLI projects. At missions, several actors participate in the administration of CFLI projects and although these practices vary among missions, there is usually a CFLI Committee which would include the Foreign Policy and Diplomatic Services (FPDS) section, a local CFLI coordinator and the HOM. The main activities undertaken at missions are:

- promoting the program to local stakeholders and potential funding applicants;

- receiving and reviewing project applications;

- negotiating/clarifying with potential funding recipients;

- preparing and approving contribution agreements for each approved project;

- making payments to funding recipients;

- monitoring projects;

- collecting the final project report; and

- submitting the final mission report to IRC.

HOMs are responsible for signing contribution agreements and approving various project and program reports, including the annual CFLI country strategy for the mission. The CFLI Committee assesses applications for CFLI funding and recommends projects for approval to the HOM. In most cases, the FPDS section is responsible for the day-to-day management of the CFLI, and is accountable to the HOM. The Management Consular Officer (MCO) provides financial management support. Local CFLI coordinators are hired, often on a contract basis, by some missions to assist the FPDS with project implementation.

1.4 Program Resources

The CFLI projects on average range between $10,000 and $25,000 CDN. Over the last two programming cycles, the average dollar amount of the CFLI projects has remained relatively unchanged. In 2013-14, the average dollar amount was $23,938 (based on a total of 292 contribution agreements signed), slightly higher than in the previous year, 2012-13, at an average of $22,585 based on 615 funded projects.

The CFLI is an ongoing program with mission-specific annual allocations. Missions are required to organize their own calls for proposals and approve projects based on the pre-determined allocations. DFATD-IRC disburses CFLI allocations to missions and missions disburse project funds to recipients. HOMs are authorized to approve projects up to a maximum of $50,000 at mission, while Assistant Deputy Ministers are authorized to approve projects valued over $50,000 up to a maximum of $100,000 for the geographic region.

A funding reserve is maintained but can only be used in exceptional circumstances to support local partners in response to humanitarian emergencies, emerging crises, natural disasters, or other priorities. The maximum amount of funding that can be disbursed through the CFLI in those cases is $50,000.

Although Treasury Board terms and conditions allow for project disbursements within two fiscal years, in practice CFLI projects are to be completed within one fiscal year, given the uncertainty surrounding annual allocations. Funds that are not used within the fiscal year cannot be carried over and must be returned to the Consolidated Revenue Fund. The MCO at mission is responsible for overseeing the financial aspects of the CFLI, such as accounting and reporting. This includes ensuring that only properly authorized payments are made and that stacking limits are respected: the sum of Canadian government assistance — including those from federal, provincial, territorial and municipal sources — cannot exceed 100% of the total project expenditures. Eligibility is governed according to GoC policies on values and ethics and respecting human rights; all projects must be for peaceful, non-military purposes.

Depending on the nature of the funding recipient, different types of agreements are established. Contribution agreements (CAs) are established with non-governmental organizations (NGOs), academic institutions or international organizations (i.e. intergovernmental organizations of which two or more states are members, such as the UN and its agencies). Memorandums of understanding (MOUs) may be established with foreign states (i.e. a state other than Canada or a department agency of such a state). DFATD's Centre of Expertise for Grants and Contributions reviews all agreements prior to signature.

In 2012-13, the CFLI received $14.7 million in grants and contributions funding and approximately $3 million in operational funding. A total of 615 projects were implemented in 2012-13. While in 2013-14, CFLI funding was reduced by 50% to $7 million and $1.4 million in operating funds. During 2013-14, a total of 292 agreements were signed amounting to $6.95 million.

Africa, the Americas and Asia were the key beneficiary regions of CFLI funding in 2012-13, with almost equal shares of the funding. In 2013-14, the Asia share increased (by three percentage points) while the Africa share decreased by four percentage points and the share of the Americas decreased by five percentage points.

Figure 1: Distribution of CFLI Expenditures by Region

Africa Americas Asia Europe Middle EastText version

2012-2013: 29%

2013-2014: 25%

2012-2013: 28%

2013-2014: 23%

2012-2013: 26%

2013-2014: 29%

2012-2013: 7%

2013-2014: 14%

2012-2013: 10%

2013-2014: 10%

1.5 Program Beneficiaries

The target population and immediate beneficiaries of CFLI programming are civil societies and the citizens in developing countries served by the program. The 2008 Official Development Assistance Accountability Act (ODAAA) requires all federal agencies and departments providing Official Development Assistance (ODA) to report its development assistance activities. All Canadian ODA, as reported to Parliament under the Act, must meet three conditions: contribute to poverty reduction, take into account the perspectives of the poor and be consistent with international human rights standards.

CFLI funding is directed to countries that qualify for ODA, as determined by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Development Assistance Committee (DAC). The list of countries eligible to receive Canadian international assistance is subject to periodic changes, which are taken into account in annual budget allocations to missions, as well as with new project approvals. Within the context of eligible countries, applications for CFLI funding can be made by a number of actors or entities. Eligible recipients include:Footnote 2

- Local non-governmental, community and not-for-profit organizations;

- Local academic institutions working on local projects;

- International, intergovernmental, multilateral and regional institutions, organizations and agencies working on local development activities;

- Municipal, regional or national government institutions or agencies of the recipient country working on local projects; and

- Canadian non-governmental and not-for-profit organizations that are working on local development activities.

The majority of CFLI funding is to be directed toward local civil society organizations (including nongovernmental organizations) and other institutions working at the local level. Other entities, such as international, intergovernmental, multilateral and regional organizations can be eligible for a contribution, provided that they are working with local partners and on local projects that are consistent with the objectives of the CFLI. Similarly, municipal, regional or national government institutions may receive CFLI funding, provided that their projects are essentially local in nature.

With respect to natural disasters and emergencies, eligible recipients are restricted to local organizations as opposed to a chapter of an international organization.

The CFLI is expected to complement the activities of various local, national, and international institutions engaged in development activity at the local level, including other federal departments and agencies that can provide specialized or unique services for a given project.

Missions are responsible for organizing calls for proposals and for reviewing applications for CFLI funding. When reviewing applications, certain factors may be given more weight than others, depending on the context in which the mission is operating and the needs faced by the local population.

2.0 Evaluation Scope & Objectives

The goal of this evaluation is to provide DFATD's senior management with a neutral and evidence-based assessment of the relevance and performance of the CFLI since its transfer to former DFAIT in 2012. The evaluation will address recommendations from previous audits and evaluations, CFLl's adherence to the ODAAA as well as the degree to which individual projects under the CFLI are contributing — at least through their outputs and, to some extent, their immediate outcomes — to the objectives of the program.

The specific objectives of the evaluation are as follows:

- 1. To evaluate the relevance of the CFLI by assessing the extent to which it addresses department strategic priorities as well as its alignment with federal government priorities

- 2. To evaluate the performance of the CFLI program and its projects, including an assessment of progress toward expected outcomes (including immediate, intermediate and ultimate outcomes as identified in the logic model) and demonstrations of efficiency and economy in program activities

- 3. To assess the effectiveness of the CFLI governance structure and program delivery mechanisms, both at HQ and at missions

- 4. To examine the efficiency and effectiveness of processes used for the approval of individual projects (including those related to natural disasters or humanitarian emergencies), mission-specific Vote 10 allocations, and the CFLI program strategic direction, as well as to determine potential overlap or duplication with other DFATD programming (e.g., Anti-Crime and Counter-Terrorism Capacity Building (ACCTCB), Religious Freedom Fund (RFF)); and

- 5. To reflect on the lessons learned from the management of individual CFLI projects at missions and the administration of CFLI at both missions and DFATD HQ, with the identification of recommendations for future project administration and overall program development.

3.0 Operational Considerations

The CFLI operates in a complex environment. For instance, CFLI funding is approved for hundreds of projects in over a hundred countries every year. Programming needs differ among missions/regions, therefore, the outcomes sought by individual projects vary substantially. Furthermore, missions' circumstances such as their size and accreditation may also affect the nature and extent of CFLI programming.

CFLI Program Managers and Coordinators at missions oversee projects and ensure funding recipients are collecting the necessary financial and performance information from beneficiaries. However, recipients are often local NGOs who may not be able to regularly report financial and performance information due to limited capacity. Furthermore, the diversity of projects and project contexts may make it difficult to establish a baseline of success or to measure the achievement of outputs and immediate outcomes.

For longer term program outcomes addressing Departmental strategic outcomes on public diplomacy and advocacy and GoC's priorities of democratic governance, security and stability, there are a number of internationally recognized indicators for developing countries. However, even if progress were measured by thematic area, it would be difficult to attribute outcomes to the program, given the number of other national and international participants who are aiming to achieve similar programming goals.

Although the CFLI is a long-running program, it has undergone a number of significant changes in the past few years, including the development of new terms and conditions, a new performance measurement strategy, and a revised strategic direction following the transfer from former CIDA to former DFAIT in 2012. Since 2012, these elements and others have undergone additional changes in order to respond to financial constraints and changing contexts. Given the recent implementation of fundamental changes to the design of the program and in the absence of baseline data, it is premature for the evaluation to assess the full effectiveness of program design and delivery. This report delivers preliminary observations.

Finally, the end of the fiscal year is an extremely busy period for the management of the CFLI, since all projects must be completed by fiscal year end and reported on soon thereafter. Much of the evaluation data collection took place during this period of intense work; therefore the timing of this evaluation may have impeded the ability of relevant stakeholders to fully participate in the evaluation thereby affecting response rates and completeness of replies. Nonetheless, the level of participation was relatively high for managers and sufficient for recipients thereby contributing to reliable and valid evaluation findings.

4.0 Strategic Linkages

The evaluation took into account a number of unique considerations when assessing the complementary role of the CFLI with other DFATD programs.

First, the CFLI funds small-budget projects that are expected to be completed within any one given fiscal year, although it has the authority to fund multi-year projects. Other DFATD programs, such as Global Peace and Security Fund (GPSF) or Development programming, support higher budget projects (with contributions frequently exceeding $1 million) that aim to achieve results over several years.

Thematically, the CFLI has potential linkages with several other DFATD programs. CFLI projects may supplement capacity building programs. The Anti-Crime Capacity Building Program (ACCBP) and the Counter-Terrorism Capacity Building Program (CTCBP) help foreign states in their prevention of and response to criminal and terrorist activity. Certain CFLI projects may contribute to the achievement of outcomes of the ACCBP and CTCBP programs.

The CFLI activities also focus on development objectives and the promotion and protection of Canadian values, including democracy and human rights. These may contribute to certain outcomes pursued by development programming, such as the Religious Freedom Fund (RFF) and the Post Initiative Fund (PIF). This evaluation specifically considered the CFLI’s complementarity with other DFATD programs, and assessed, as well as considered the opportunity for strategic linkages.

The CFLI is also designed to enable quick responses to natural disasters and humanitarian emergencies which offer an opportunity for immediate humanitarian relief, as an interim strategy, towards more comprehensive humanitarian programming. Successful application of the CFLI largely depends on mission strategies that encompass complementarity among the CFLI, policy-centers such as Office of Religious Freedoms, development and trade programs.

In addition, the evaluation examined the inclusiveness of CFLI in mission strategies. The CFLI Terms and Conditions allows for the reallocation of funding from other programs to CFLI to address concerns that are considered important to Canada's foreign policy interests.

5.0 Evaluation Approach & Methodology

The evaluation covers the first two years of CFLI activity under the responsibility of DFATD, i.e. 2012-13 and 2013-14. The evaluation matrix forms the foundation for addressing the findings to the issues, key questions, indicators, and sources of data.

5.1 Evaluation Design

The CFLI evaluation used a mixed-methods approach combining primarily qualitative information from various sources with some qualitative and quantitative data obtained from project files and surveys of Heads of Missions, CFLI program managers, and CFLI recipients. Moreover, the implementation of the methodology adopts a hybrid management model with the DFATD evaluation unit (ZIE) carrying out part of the data collection and a consulting team completing the data collection and conducting the analysis and reporting.

5.2 Date Sources

5.2.1 File and Document Review

The File and Document Review supplied information for the analysis of consistency with federal roles and responsibilities, the assessment of relevance and performance, as well as the effectiveness of the governance structure and delivery systems. The key sources were:

- procedural documents (terms and conditions, guidelines, Acts of Parliament);

- program administration data;

- mission plans; and,

- annual mission reports.

The annual mission reports reviewed were year-end reports that included information on results achieved per project. Results relevant to the indicators and the evaluation matrix were compiled in an Excel-based data base. A sample of thirty (30) reports was based on:

- Quota samples of roughly the same proportion by region.

- Missions selected for key informant interviews were excluded, with the exception of the Asia region where all missions had been selected for interviews (so all missions in this regions were included in both interviews and file review), and Europe, where only four non-interview missions were left to select from.

- Missions were randomly selected within regions, using a random generator that also took into account the amount of funding allocations.

- Fiscal year of reporting was selected randomly between the two years covered by the evaluation.

- Files were reviewed for completeness of reports; in the absence of mission reports, the other fiscal year was reviewed for completeness to serve as a replacement. If neither fiscal year contained mission reports, another mission was randomly selected serving as an alternate.

- Randomly selected three project files per mission were also reviewed.

Twenty mission plans were reviewed for information relevant to the evaluation indicators. The reports were sampled as followed:

- It was decided to include a subsample of the missions selected for file review of mission reports, i.e., 20 of the 30 selected missions, for the same years.

- Twenty missions were randomly selected from the 30.

- Files were reviewed for completeness. If no mission plan was found, the other fiscal year was reviewed for completeness and used as a replacement. If neither fiscal year contained a plan, an alternate mission was randomly selected.

5.2.2 Key Informant Interviews

Three types of key informant interviews were conducted:

- Group 1: 22 individual interviews of DFATD headquarters (including the following non-mutually exclusive categories: CFLI coordinators, mission staff, geographic directors, staff directors, program advisors, IRC staff, and senior managers);

- Group 2: interviews conducted by ZIE staff in the context of site visits for another unrelated evaluation which occurred at the following missions with active CFLI projects Jordan, Guatemala, Belize, and Jamaica.

- Group 3: 10 individual telephone interviews of CFLI program managers active in missions. Missions were sampled randomly within regionsFootnote 3; overlaps between individual interviews and the selection of mission reports for secondary analysis were avoided to the extent possible in order to gather input from more missions.

A total of 34 key informant interviews were conducted which generated over 150 pages of interview notes.

5.2.3 Heads of Mission Questionnaire

HOMs approve and sign CFLI contribution agreements up to $50,000 and they are responsible for approving an annual CFLI strategy. Because of their role, the evaluation conducted an on-line survey of all HOMs involved in the administration of CFLI.

The questionnaire included four open-ended questions to provide HOMs an opportunity to describe the value of the program. The invitations to participate in this survey were sent on February 28, after an information message was issued by the program division; reminders were issued on March 12 and March 23. A total of 41 of 68 questionnaires were completed by HOMs, representing a response rate of 60%. This level of participation provides a level of confidence that the results represent the views of HOMs in general.

5.2.4 Survey of CFLI Program Managers

CFLI program managers were approached in two ways to provide their views on the program: individual telephone interviews described earlier and through an on-line survey.

All CFLI program managers not sampled for individual interviews were asked to complete an on-line questionnaire which was a subset of the evaluation issues. A total of 55 managers were invited to this questionnaire on February 28 after an information message was issued by the program division. Reminders were sent on March 12 and March 23. A total of 43 of 55 questionnaires were completed by program managers representing a response rate of 78%. This high response rate provided a level of confidence in the reliability of the responses.

5.2.5 Survey of Recipients

Recipients were defined as organizations who apply for funding and receive CFLI support – as opposed to beneficiaries who are the individuals who would be the direct recipients of services and outputs funded by the CFLI. This evaluation reached recipients who in turn would be able to provide input on the relative impact of CFLI to direct beneficiaries of this funding.

Recipients are grass-roots organizations, often small, which may not have access to Internet, or the ability to fully communicate in English, French, or Spanish, or work on sensitive issues – any of these circumstances may impede their ability to fully engage in the evaluation’s data collection approach. The survey population was therefore limited to those able to understand a questionnaire in English, French, or Spanish and in a position to access a survey on the Web. The questionnaire for recipients included only close-ended questions to simplify the respondents' task and to reduce the risk of misinterpretation in the translation of foreign languages.

A random sample of 200 recipient organizations was drawn from the two fiscal years covered by this evaluation which was further stratified by project size to ensure representation of projects of different sizes. CFLI program managers and/or coordinators were asked to perform two tasks:

- to identify recipients who would be unable to complete the questionnaire because of technical restrictions, language barriers or given the nature of their work; and,

- to relay a message to recipients who could access a survey to ask them to complete the on-line questionnaire.

A total of 58 program managers oversaw the 200 selected projects. A total of 41 or 71% of program managers accessed the list of recipients. Seventy-seven (77) or 39% of a possible 200 recipient questionnaires were completed. Although the recipient survey response rate is relatively low compared to the HOM and CFLI program managers, it is sufficiently high to provide a level of confidence in the reliability of the survey results.

5.3 Data Analysis

Program administration data for 2012-13 and 2013-14 were used primarily to describe program usage and to document administration efficiency. Descriptive analysis was performed based on project-level data aggregated by country, mission, or region.

Results from the survey of recipients and from the survey of program managers were compiled using specialized analytical software tool (i.e. SPSS). Descriptive analysis was conducted based on aggregated responses by country, mission or region.

Results from HQ interviews, HOM questionnaires, and program manager interviews were structured and coded according to evaluation issues with the use of specialized qualitative data analysis software (Dedoose). Data was coded as positive (supportive of program results and outcomes), negative (not supportive of program), or neutral (informative, without a judgement direction). Data analysis consisted of delineating trends, patterns and outliers as well as cross-referencing and validation of information.

5.4 Reliability, Verification & Validation

The evaluation process aims to ensure that information and findings are reliable, have been validated, and can be verified. In particular, information collected through interviews and surveys was triangulated with several informants and secondary sources to ensure confidentially. Data analysis was performed in a structured manner which allowed reference to the original quantitative or qualitative data for quality assurance. The evaluation presents findings and conclusions based on the convergence of data/information from various sources. Additional comments or outliers are reported as observations.

5.5 Evaluation Governance

An Evaluation Advisory Committee with representatives from Capacity Building Programs (IGC), Deployment and Co-ordination (IRC), Stabilization and Reconstruction (IRG), Democracy (IOL) reviewed the evaluation work plan and provided input on the evaluation. The evaluation was managed by ZIE with the assistance of an external consultant. The consultant was asked to assist in the operational planning of the evaluation, its implementation, the analysis, and reporting under the supervision of ZIE but with independence to ensure neutrality of findings and recommendations.

6.0 Limitations To Methodology

Although the evaluation is based on many different sources, most sources were program-related. To be more specific, most documentation presented as evidence was produced by program management (at HQ or in missions), derived from interviews with DFATD managers (several of whom were associated with the program) or directly collected through surveys with HOMs who were responsible for the program locally and with CFLI program managers. The homogeneity of sources therefore used for this evaluation increases the potential for bias. To mitigate this risk of bias, ZIE conducted interviews with stakeholders that are not directly involved in the administration of the CFLI. They included managers, thematic specialists, colleagues from the development side, and former CFLI recipients.

There also were many operational and logistical challenges related to surveying CFLI recipients. First, many CFLI recipients may not have been proficient in either of the two official languages to fully respond to a survey. For this reason, the recipient survey was translated into Spanish, allowing wider coverage in central and South America. The sample of recipients however was also constrained by the availability of the questionnaire in English, French, and Spanish only, and for those who were able to access the survey online.

Other data quality limitations under consideration included the ability of CFLI recipients to fully reply to an online survey because of limited broadband availability or due to the security of the internet in certain countries. In response to internet accessibility, recipients were provided with extended timelines to respond to the survey. CFLI program managers were also asked to review the proposed list of recipients to ensure recipients would not be compromised if they participated in the survey. Despite these sampling limitations, the response rate of recipients was deemed sufficient to report findings.

7.0 Evaluation Findings

7.1 Relevance Issue 1: Continued Need for the Program

Consideration for the need of the program deals with the position of the CFLI in DFATD's and Canada's international assistance programming, the usefulness of the CFLI as rapid response in cases of natural disasters or humanitarian emergencies, and the response to the needs of priority countries.

Finding #1: The CFLI fills a much-needed niche of its own in international assistance programming.

There were very few dissenting views regarding the position of the CFLI within international assistance programming. It is viewed as one of the only tools available to missions to act tangibly to further the foreign policy objectives of Canada. HOMs, CFLI program managers, and HQ managers agree that the CFLI is essential to achieve a number of mission goals, in particular the promotion of democracy and human rights. The CFLI is seen as effective in achieving such results as well as in enhancing the capacity of targeted groups to undertake initiatives on their own. The CFLI is also considered to be an effective tool to develop networks and the only tool to develop networks with civil society.

According to HOMs and CFLI program managers, the CFLI is particularly important in filling a much needed gap in countries that do not benefit from development/aid programming and in the absence of any other bilateral programming. In these cases, the CFLI is a positive vehicle to contribute to enhancing Canada’s image.

HOMs and CFLI program managers insisted that the CFLI is also unique because it is flexible, locally-managed, and responsive to local needs. While the nature and scope of CFLI programming has narrowed with the move of the program from former CIDA to former DFAIT, missions still have an important role in the identification of the local priorities and the selection of the local partners and projects. Missions see the CFLI as an adaptable tool which still offers enough flexibility to be responsive to local situations in a useful manner. Its focus can be shifted from country to country, as mission plans determine. The CFLI also supports innovation in network building because it can be used to fund new partners (and test their ability to deliver) with limited amounts of money and risk.

In several interviews, HOMs, HQ managers, and CFLI program managers indicated that the CFLI projects are often cited as producing positive results at local levels which have heightened public visibility. There still remains, though, a source of tension among the various managers of the CFLI (HOMs and program managers) between the current foreign policy objectives assigned to the program and the development objectives that initially drove the CFLI. While most have found the CFLI useful to express foreign policy objectives, some long for the days when the CFLI could be used to assist countries as a development tool – addressing local development needs rather than promoting Canadian values and interests through diplomatic advocacy.

HOMs, CFLI program managers, and HQ managers have also expressed concerns over the long-term viability and productivity of the CFLI given its reduced budgets. Some were of the view that diminishing resources devoted to the CFLI could lead to reputational damage for Canada and could reach a point where questions would be raised about the value of continuing the CFLI when funds are so limited. While the reductions incurred between 2012-13 and 2013-14 were substantial and affected the capacity of the program to deliver, many HOMs, CFLI program managers, and HQ managers indicated that the investment is still worthwhile.

HOMs, CFLI program managers and HQ managers reported that further downsizing of the CFLI or its discontinuation would adversely affect Canada's capacity to influence the movement of human rights and democracy. However, there were some CFLI program managers and HQ managers who viewed that the impact of discontinuation would be minor. They argued that the CFLI is already a very small program and that, presumably, the impact of discontinuation would not be severe. Yet, others indicated that the loss of the CFLI would be have a greater impact in small countries where Canada has no direct diplomatic presence as opposed to large countries where the CFLI is one of other Canadian programs thereby rendering the CFLI to be less visible or relevant.

Finding #2: The CFLI is useful for rapid response to emergency situations but small project budgets limit its role.

In 2012-13, 3.9% of CFLI funding ($539,259) was associated with humanitarian response to emergency situations; while the proportion was higher at 9.8% ($684,622) in 2013-14. The CFLI expenditures on humanitarian response vary greatly by region from year to year depending on conditions (and, obviously, need for such response): for example, none of the CFLI expenditures in Europe in 2012-13 were for humanitarian response, whereas one-third of the CFLI expenditures in Europe in 2013-14 were associated with such circumstances.

| 2012-2013 | 2013-2014 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFLI $ | % of total CFLI $ | # of projects | CFLI $ | % of total CFLI $ | # of projects | |

| Total | $539,259 | 3.9% | 21 | $684,622 | 9.8% | 22 |

| Africa | $48,150 | 1.2% | 3 | $50,000 | 2.9% | 1 |

| Americas | $142,600 | 3.7% | 4 | $19,919 | 1.2% | 1 |

| Asia | $197,479 | 5.4% | 9 | $273,809 | 13.7% | 11 |

| Europe | $0 | 0.0% | 0 | $305,024 | 32.1% | 7 |

| Middle E. | $151,030 | 11.3% | 5 | $35,870 | 5.2% | 2 |

Whether the CFLI is a useful response mechanism for emergency situations varied among informants. Some HOMs, CFLI program managers, and HQ managers cited successful efforts (e.g. Togo, Chad, Benin, Mali, Morocco, Sri Lanka, the Caribbean, Chile, Albania, Serbia, and Ukraine). Considering the limited funds available, the CFLI is well-positioned as an early specific, often one-time allocation of funds prior to, or in the absence of, large-scale traditional humanitarian assistance. While the CFLI provided limited relief, such projects often produced great visibility and therefore contributed directly to the diplomacy and advocacy objectives of the program.

Others respondents reported that the very limited CFLI funds available did not permit significant action: "If Canada is going to give emergency funds, it can be done quickly and in much more significant amounts through ministerial/cabinet decisions."

Some respondents also indicated that delays in program allocations in recent years and lack of predictability of funding have impaired the ability for the CFLI to support humanitarian response throughout the year. Moreover, some indicated difficulty in receiving emergency response funds approved because of a lack of urgency or tardiness in the financial cycle which did not allow for fiscal year-end cash management.

About one-quarter of the CFLI recipients indicated that, between April 2012 and September 2014, they were involved in a CFLI project in response to a natural disaster, an emerging crisis, or a humanitarian emergency. Of them, 83% (15/18) stated that the CFLI assistance was made available at the right time to support much needed relief.

Finding #3: The CFLI responds to only some local needs of priority countries given the demand for the CFLI, as demonstrated in the high number of applications, which far exceeds acceptance rates for CFLI funding.

Based on a sample of mission reports covering fiscal years 2012-13 and 2013-14, missions received on average 93.1 applications per year. An average of 7.8 applications was selected and 7.2 were implemented representing an acceptance rate of 7.7% (7.2/93.1). Although this suggests a low rate of acceptance given the high interest or demand for CFLI funding, it does suggest a high rate of funding CFLI projects that have been selected to target a significant need. It also suggests that limited CFLI funding may impede the ability to meet the demand for such.

Missions use three main strategies to solicit applications: a) advertising/calls for proposals – sometimes quite broadly, in local newspapers and media; b) word of mouth, and c) targeted requests to known entities. Some missions reported that to deal with delays in obtaining annual allocations, they returned to past organizations that had been successful in receiving CFLI funds rather than soliciting proposals through a competitive process. This approach limited the effectiveness of the program to build new networks.

Relevance to the priority needs of countries is mentioned in mission reports among the selection criteria for CFLI projects. In some of the missions, discussions with governments and/or other missions and donors were held to identify priority needs of countries. In two cases in particular, formal multiparty consultations were held, whereas in others, priority-setting appeared to be ad-hoc and informal. Missions were also found to orient CFLI funds to areas of common priority between Canadian interests and local priorities, strategically establishing a zone of common purpose. For example, a focus on equitable and sustainable economic growth was redesigned as social and economic inclusion of disadvantaged groups that were important to the local administration.

According to the HOMs, CFLI program managers, and HQ managers consulted, the overwhelming message was that the CFLI responds to needs or is flexible enough to respond to local needs: "themes are formulated in such a way that they can actually be quite inclusive, and it wouldn't be difficult to find a need in virtually any country that matches the broad and encompassing priorities put forward under the CFLI."

By contrast, some survey respondents emphasized that the CFLI has moved away from responding to development needs and moved towards human rights. The CFLI no longer seems relevant in its support of significant development needs of local communities but rather, in the DFATD version of the CFLI, missions must align CFLI initiatives with Canadian foreign policy priorities which may not reflect local communities’ immediate needs.

7.2 Relevance Issue 2: Alignment with Government Priorities

Finding #4: The CFLI mandate and goals align with DFATD priorities as well as with the International Assistance Envelope thematic priorities.

As noted in the 2013-14 PAA, the CFLI was aligned with Strategic Outcome 1, "The international agenda is shaped to Canada's benefit and advantage in accordance with Canadian interests and values". Under diplomacy and advocacy, the CFLI was considered part of the international assistance program governance, which included four other programs (Global Partnership Program, the Capacity Building Programs, the Investment Cooperation Program, and the Religious Freedom Fund).

By definition, and according to the Department’s PAA, the CFLI would not contribute to the other strategic outcomes such as commercial and consular services or the maintenance of a mission network of infrastructure and services, but the CFLI is not positioned under the reduction of poverty for those living in countries where Canada engages in international development.

Since the CFLI is funded from the IAE, it must align with at least one of the IAE thematic priorities. While the CFLI was managed under the five IAE thematic priorities in 2012-13, there was a shift of focus in 2013-14 to more specific priorities. Notwithstanding, priorities in the second year of the reference period remain well aligned under the IAE thematic priorities. For instance, the 2013-14 priorities of “promoting human rights” and “preventing sexual violence” contribute to the IAE priorities of “advancing democracy” and “building security and stability”.

| Priority area | 2012-2013 | 2013-2014 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount ($) | % of total CFLI $ | Amount ($) | % of total CFLI $ | |||

| Year 1 IAE Priorities | Children and youth | 3,885,693 | 28,0% | |||

| Food Security | 414,678 | 3,0% | ||||

| Security and Stability | 1,411,091 | 10,2% | ||||

| Year 2 IAE Priorities | Stimulating Economic Growth/ Strengthening Economic Governance | 1,952,197 | 14,1% | |||

| Supporting Democratic Transition/ Advancing Democracy | 5,686,636 | 40,9% | 2,722,303 | 38,9% | ||

| Humanitarian Response | 539,259 | 3,9% | 684,622 | 9,8% | ||

| Protecting Human Rights | 2,314,051 | 33,1% | ||||

| Preventing Sexual Violence | 1,268,670 | 18,2% | ||||

| Total | 13,889,554 | 100,0% | 6,989,645 | 100,0% | ||

Finding #5: The CFLI contributes to the GoC's international priorities and to advocacy of Canadian values and priorities.

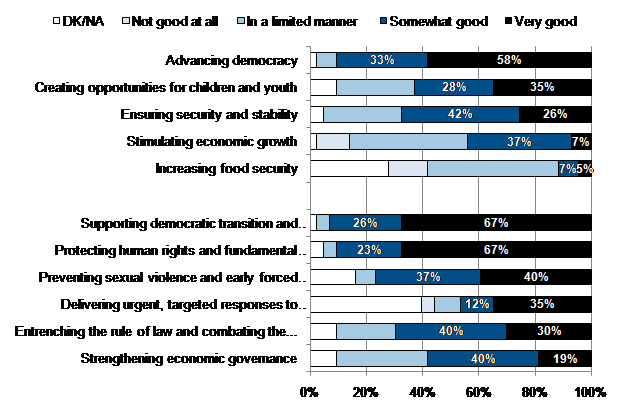

Objectives and strategies outlined in 2013-14 mission plans were most prominently connected to a subset of IAE priorities: (1) protecting human rights and fundamental freedoms, including religious freedom and LGBT rights; (2) preventing sexual violence and early forced marriage; and (3) supporting democratic transition and expanded democratic participation, particularly by women and minority groups. Very few CFLI projects corresponded to the priority of delivering urgent, targeted responses to disasters or emerging crises. Some associated directly with the priority of (4) entrenching the rule of law and combating the destabilizing impact of crime and corruption, by reinforcing the civil society organizations or strengthening media or journalism. The fifth priority, (5) strengthening economic governance, was also addressed indirectly, through a few projects that aimed to develop economic growth/assets for women.

Mission plans also noted that they intended to work in alignment with CFLI thematic priorities such as increasing food security, creating opportunities for children and youth, stimulating economic growth, advancing democracy, and ensuring security and stability.

Finding #6: The shift in program direction for the CFLI has confounded the ability to clearly ascertain the degree to which CFLI initiatives are in line with ODAAA conditions.

According to Program Guidelines (August 2013, page 14), the CFLI is to satisfy reporting requirements under Canada's Official Development Assistance Accountability Act (ODAAA) and for the OECD Development Assistance Committee (OECD DAC).

As noted above, the ODAAA established three conditions that international aid must satisfy to qualify as official development assistance:Footnote 4

- 1. it must contribute to poverty reduction;

- 2. it must take into account the development priorities and perspectives of aid beneficiaries; and

- 3. it must be consistent with international human rights standards

However, the evaluation found it was difficult to determine the extent to which compliance to ODAAA was achieved given the shift in program direction in 2013-14 to support narrower priorities, which as mentioned in finding #4, seems to only partially include ODAAA conditions. It should be noted that the evidence presented is not expert as it is not based on a legal analysis of the program activity and projects, but offers perspectives based on survey replies and accounts in mission plans over the compliance of the CFLI to ODAAA conditions.

Mission plans had situated the CFLI as a means to respond to the ODAAA condition on poverty reduction by its effort to fund projects that develop capacities for those who were potentially in poverty. Survey replies, by contrast, indicated that poverty reduction was not achieved in most projects. Accounting for the perspectives of the poor was more frequent in that four CFLI program managers out of ten indicated that such perspectives were taken into account no more than "some of the time" during consultations with beneficiaries.

Mission plans also reported CFLI funded projects that specifically addressed human rights issues such as early forced marriage or LGBTQ rights which would be consistent with international human rights standards. Consistency with international human rights standards was considered in most CFLI projects by nine program managers out of ten.

Figure 2: Delivery on ODAAA conditions according to CFLI program managers

( "Based on your experience with CFLI and excluding projects aimed at alleviating the effects of a natural or artificial disaster or other emergency, how frequently do CFLI projects..."; n = 43)

...show consistency with international human rights standards? ...take into account the perspectives of the poor? ...contribute to poverty reduction?Text version

Never: 8%

Some of the time: 2%

Most of the time: 23%

Always: 67%

Never: 7%

Some of the time: 37%

Most of the time: 40%

Always: 16%

Never: 14%

Some of the time: 49%

Most of the time: 35%

Always: 2%

Interviews with key informants led to the same conclusion. HOMs and CFLI program managers indicated CFLI most likely addressed the ODAAA condition on human rights standards but that only some projects directly addressed poverty reduction. Some key informants indicated that poverty reduction was addressed through CFLI's impact on grass roots capacity building.

Based on key informant interviews and survey respondents, it is not surprising then that a contribution to poverty reduction was significantly less evident in country level CFLI strategies given that the program was realigned in 2013-14 toward foreign policy objectives rather than development objectives. As presented in Table 2, 2012-13 priorities on "strengthening economic governance" and "food security" were shifted in 2013-14 for increased attention to "protecting human rights" and "preventing sexual violence".

Approximately 75% of survey recipients reported asking beneficiaries about their needs when planning their projects supported by the CFLI, while one in five stated that they do so in some cases. Beneficiaries were consulted in conversation and exchanges (86%), in the preparation of their action plan (60%), through research (55%), and conversation and exchanges with experts (40%). Surveyed recipients noted that perspectives of the poor were achieved through consultations with beneficiaries.

During the reference period of this evaluation, 2012-13 to 2013-14, it was difficult to ascertain the CFLI’s compliance to ODAAA given that the CFLI is positioned under Diplomacy and Advocacy in the Department’s PAA rather than under International Development. This had to some degree confounded the ability to clearly determine the degree to which CFLI priorities were in line with ODAAA conditions. It suggested that the CFLI, under its present program direction, was not well equipped to deliver on all ODAAA conditions.

7.3 Relevance Issue 3: Consistency with Federal Roles and Responsibilities

Finding #7: DFATD and IRC are appropriate locations for the management of the CFLI.

The Department's mandate is set out in the Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Act enacted June 26, 2013.Footnote 5 The Minister of Foreign Affairs is responsible for the conduct of all external affairs of Canada, including international trade and commerce. As per the Act, the Department's mandate includes but is not limited to the following:

- conducting all official diplomatic communications and negotiations between the Government of Canada and other countries and international organizations;

- coordinating Canada's international economic relations and foster the expansion of Canada's international trade and commerce; and,

- managing Canada's diplomatic and consular missions and services abroad, including the administration of the Canadian Foreign Service.

The Minister is also empowered to develop and to implement programs related to the Minister's powers, duties and functions for the promotion of Canada's interests abroad. DFATD is therefore clearly mandated to manage the CFLI. In fact, it is the only Government of Canada organization that possesses such a mandate.

Survey respondents and key informants uniformly agreed IRC is best positioned for the management of the CFLI. Only a few HOMs, CFLI program managers, and HQ managers, would prefer to see CFLI managed by a development unit, but most stated that IRC is appropriate given CFLI’s objectives and in consideration of the synergies and potential for complementarity relationships among other programs in IRC. The main reasons for supporting the CFLI in IRC were as follows: The CFLI's priorities align with diplomatic and political activities; few other divisions have resident expertise in programming; The CFLI should complement much larger programs; and, development activities and programming are based on longer-term objectives which differs from those of the CFLI.

Most survey respondents were generally satisfied with IRC and found IRC responsive to inquiries and client feedback. Some respondents noted however, that the performance of IRC may have been hindered by regular staff turnover and an understaffed office. Others expressed some concerns on the ability of IRC to provide reliable responses to financial questions. Some also preferred IRC to be more proactive in developing communications materials promoting the usefulness and results of the CFLI.

Finding #8: Although most stakeholders understood roles and responsibilities, further clarity on eligibility for CFLI to support emergency relief and project approvals was requested.

The CFLI program guidelines (2013) clearly outline the roles, responsibilities and accountabilities of the various stakeholders involved in the administration of the program. The majority of key informants and survey respondents were of the view that that roles and responsibilities were clearly delineated.

However, some key informants voiced concerns over whether CFLI emergency programming met humanitarian guidelines. Another area of concern was over the renegotiation of agreements: "IRC said that this was at the discretion of the HOM but HQ must agree to amendments to contribution agreements."

Finally, another area that was seen as unclear was on the respective roles of the HOM and of HQ in approving projects. Some stakeholders were of the opinion that the oversight role carried out by IRC for project approval overlapped with the approval authority delegated to the HOM.

7.4 Performance Issue 4: Achievement of Expected Outcomes

The CFLI logic model identifies four immediate outcomes, three intermediate outcomes, and one long-term outcome.

Finding #9: Within its limited resources, The CFLI contributes to the awareness of Canadian values amongst local stakeholders.

The first expected immediate outcome of the CFLI is to increase awareness among local stakeholders of the Canadian values of democracy, security and stability. Although mission reports did not identify the types of recipients, many organizations were listed such as:

- the country level operational arms of large, international development charities or NGOs such as Caritas, Oxfam, Save the Children, Mennonite Economic Development Associates;

- the country-level operational arms of large national development charities, from countries such as Italy and Norway;

- universities or university-based or affiliated research entities, within country;

- foundations;

- local or regional nongovernmental organizations including economic cooperatives, associations of individuals or groups with like-minded interests (these included in some countries human rights or civil society activist organizations or federations of such organizations);

- schools;

- health centers or rehabilitation centers.

Annual mission reports indicated the mission would actively promote the positive effect of CFLI projects during high-level meetings, visits or in local media. Such visibility increased awareness of Canadian values of democracy, security and stability. It was also noted that in some cases missions may reserve active promotion of the CFLI. However, in general, it seemed to be taken for granted that projects funded by Canadian government automatically promoted Canadian values of democracy, security and stability.

Examples of increased awareness were found at multiple levels across the missions examined, ranging from local levels (for example, where small groups of youth were being provided with training on tolerance and cooperation, stated as contributing to post-conflict capacity for democracy and stability) to a more macro level (for example where a foreign government agreed to allow the construction of hospital facilities to support maternal and child health).

Cases of increased awareness of Canada's values occurred particularly when the organizations selected to receive CFLI funds were first-time recipients. It was noted that in some countries, Canada has acquired a reputation of being able to work with civil society on issues that other countries would prefer not to address because of their sensitivity, for example.

- Although international donors (embassies) focus on women's and children's projects, many appeared to shy away from the more sensitive or controversial human rights defenders and democracy/governance projects. In one country, Canada was seen as one of the few donors willing to work on such sensitive projects.

- In another country, Canada's image was also enhanced through the CFLI. Among the local civil society, Canada was seen as very proactive, not afraid to work in areas other countries prefer not to, such as maternal death, violence against women and to promote the passing and implementation of the human trafficking law.

There were cases where CFLI projects had been used incrementally towards achieving increased awareness of Canadian values, by creating opportunities for the mission to further advance those values in other intergovernmental contexts. According to mission reports, in these instances, it appeared that the CFLI was sometimes in conjunction with a larger diplomatic toolbox that missions could strategically use in coordinated and coherent suites of strategies to further awareness of Canadian values.

An interesting issue came up in one case where it was reported that due to internal decisions related to funding, management of the local CFLI program would not be outsourced to a local consultant as in the past, but rather managed internally. This had the unexpected effect of putting “a Canadian face” on the projects, which seems to have led to multiple increased opportunities for media attention and visibility, with mission staff becoming the spokespersons for the projects.

HOMs, CFLI program managers, and HQ managers expressed positive views on the results of the CFLI regarding awareness of the Canadian values. Examples cited typically do not refer (or do so indirectly) to the values of democracy, security, and stability, referring rather to human rights, forced marriage issues, advocacy for minority groups (especially LGBT), religious groups, and building the capacity of local civil society.

Finding #10: The CFLI contributes to increased access by Canadians to key decision makers.

The second immediate expected outcome of the CFLI is to increase access by Canadians to key decision makers.

Access to key decision makers can be achieved through local media coverage in country. Media coverage was a way to measure heightened visibility of missions in their ability to better promote Canadian priorities and interests in the country. The CFLI project files were a source of information that clearly showed CFLI projects contributed to enhanced access to key decision-makers.

- While mission reports reported the extent of CFLI coverage, it was noted that for some projects short project time frames limited the ability to provide a more fulsome media strategy resulting to only a few social media posts.

- Media coverage was best achieved through project or program launch events accompanied by a press conference or when the funding awards were announced publicly. Missions also sometimes held end of program events.

- There were many instances of CFLI project summaries in local journal articles, references and links to radio or other online media coverage. CFLI projects also factored into interviews held with project managers. Coverage was reported in both local and international languages.

This evidence suggests fulsome coverage of the CFLI and mission seized opportunities to maximize CFLI coverage in local media. In addition, interview data (HOMs, CFLI program managers and HQ managers) included several examples of how the CFLI contributed to increased access to decision makers. It was found that CFLI projects placed missions in contact with local leaders who were impressed by the CFLI’s orientation to produce tangible results in local communities. According to some, the CFLI helped build relationships and ensured one channel of communication; it provided the mission with opportunities to expand and deepen already existing contacts in the wide range of political, civil society, academic, media and business networks.

Finding #11: Through CFLI projects, local stakeholders gained access to information, facilities, and tools to support security and stability efforts and to advance political-economic sustainability in their communities.

The third immediate expected outcome of the CFLI is to increase access by local stakeholders to information, facilities, and/or tools needed to support security and stability efforts and to advance political-economic sustainability in their communities.

Based on country reports sampled and analysed, CFLI projects had increased access by local stakeholders to information, facilities, and/or tools to support security and stability efforts to advance political-economic sustainability in their communities. Specific examples suggested access was increased in the following ways:

- through access to open and transparent media, avenues for public expression, or other platforms for citizen participation;

- through developing the capacity of civil society organizations to create such opportunities and platforms for themselves; and,

- through direct education and information provision on specific content issues related indirectly to Canadian values and directly to the program orientations and priority target populations.

HOMs, CFLI program managers, and HQ managers, both in interviews and survey replies, expressed the positive effects of the CFLI regarding the provision of benefits to local stakeholders.

Finding #12: In at least 25% of humanitarian emergency initiatives, the CFLI has built the capacity of local communities or organizations to respond to natural disaster and emergencies.

The fourth and last expected immediate outcome of the CFLI is to increase the timely capacity by local populations to support humanitarian assistance efforts within communities affected by natural disasters, emerging crises and emergencies.

There is some evidence that CFLI projects funded in the years examined contributed to increased local capacity to respond to natural disasters and emergencies. There is ample evidence to suggest that CFLI funds were used to immediately respond to crises thereby increasing the capacity of local organizations for a determined short-term period. However, only a small number of CFLI funded initiatives were actually designed to build the emergency resilience of local communities. Examples of such initiatives include efforts to build the capacity of local organizations to respond to increased refugee flows in Lebanon and Jordan, as well as, the training of first aid respondents in Ukraine. For all instances where the CFLI was used to build the capacity and resilience of local communities, this was to respond to man-made emergencies, rather than natural disasters.

Nevertheless, the ability of the CFLI to build sustained capacity is limited by the amount of funds provided and because of the short-term duration of the projects. HOMs, CFLI program managers, and HQ managers, both in interviews and survey replies, reported that approximately half a million dollars per year is a relatively low sum of money to build disaster resilience in local communities.

Finding #13: The CFLI contributes to networking with civil societies and local decision makers.

The first expected intermediate outcome is that the CFLI improves Canada's networks with civil society actors and the ability to influence local decision makers. Mission and project reports provided substantial evidence that the CFLI has in fact contributed to such networks. However, it is not possible to conclude from these accounts whether this was increased access, access that was already in place, or if this would have happened in the absence of the program and project funding. It should also be noted that data on this indicator was more likely to be found in the project reports than in the mission reports.

The various types of decision-makers accessed directly mentioned in mission and project reports included:

- elected officials at various levels of local, regional and national government ;

- ministerial officials;

- legal and justice system, including judges, lawyers, court clerks and bailiffs;

- managers of service agencies.

At the local or regional level, examples of connections to decision-makers were described. Developing these connections and achieving influence on local decision-makers was sometimes designed to help facilitate change within those regions, but sometimes also to buttress approaches to change at the level of the national government. These connections were often aimed at traditional leadership around practices and policies related to human rights objectives associated with Canada's mission.

In some cases indirect access to decision-makers at various levels was attempted, for example,

- by supporting watchdog organizations and processes for local, regional or national elections to model democratic processes and expose fraud to decision-makers;