Final Report:Horizontal Evaluation of Canada’s Enhanced Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Strategy

Prepared by the Diplomacy, Trade and Corporate Evaluation Division

Global Affairs Canada

July 2020

Table of Contents

Executive Summary

This horizontal evaluation reviewed the 2014 Enhanced Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Strategy, titled Doing Business the Canadian Way: A Strategy to Advance Corporate Social Responsibility in Canada’s Extractive Sector. Through the Strategy, the Government of Canada sets out its expectation that Canadian extractive sector companies will reflect Canadian values in their operations abroad. In addition to guidance aimed at Canada’s private sector, the Strategy also provides Government of Canada representatives with a “framework to guide their efforts” in the CSR space. The evaluation examined the relevance, effectiveness, and coherence of the Strategy, and was conducted in-house by Global Affairs Canada’s Diplomacy, Trade and Corporate Evaluation Division, in collaboration with Natural Resources Canada.

Five years after the development of the CSR Strategy in 2014, Canada remains a key player in the global extractive industry. The nature of this industry is complex, with significant potential to impact both local communities and Canada’s reputation writ large. As such, the evaluation found a continued need for Government of Canada support and guidance in the CSR space. However, shifts in Canada’s foreign policy priorities and an evolution of the responsible business conduct landscape have emerged since the Strategy’s development, marking it as dated.

The evaluation found that enhanced efforts to foster networks and partnerships, which is a key component of the Strategy, have contributed to Canada's reputation as an honest broker and convenor of multi-stakeholder dialogue abroad. Through both bilateral and multilateral efforts, the Government of Canada has contributed to a more stable, transparent and predictable investment environment.

While the Strategy promotes dialogue toward dispute resolution through Canada’s non-judicial mechanisms, the evaluation found that stakeholders did not frequently access them due to a lack of awareness and/or perceived ineffectiveness.

A variety of tools and resources have been developed by various Government of Canada departments to support Canadian companies in their efforts to implement the Strategy abroad. Though widely-perceived as relevant to extractive sector operations, some tools were not easily accessible nor adaptable to challenging host country contexts.

The evaluation found that staff at Global Affairs Canada approached CSR as a whole-of-mission endeavour, requiring the active participation of the department’s trade, diplomacy and international assistance business lines. On a broader level, no overarching governance structure was found to be in place between Global Affairs Canada and Natural Resources Canada despite the Strategy being a horizontal initiative. The evaluation further found that CSR-related activities across government departments were developed and implemented in silos.

Finally, the CSR Strategy was designed without a number of key components to make it a robust strategy. This impacted the way in which it was understood and applied by stakeholders.

Summary of Recommendations

Revise the Strategy based on consultations to include such elements as:

- A mission, vision and overall objectives of the Strategy.

- Clearly identified target audiences.

- Updated tools and resources, including current voluntary dispute resolution mechanisms available.

Develop a plan to guide the implementation of the Strategy, which could include the following:

- A formalized governance structure for decision-making, and clearly articulated roles and responsibilities of participating departments.

- A performance measurement framework that identifies benchmarks and metrics for success, timelines for action, as well as a mechanism to monitor implementation.

- A communication plan, including an outreach plan for targeting all key stakeholders, especially small and medium enterprises.

- A Memorandum of Understanding between the available voluntary dispute resolution mechanisms to distinguish functions and processes to avoid duplication.

Program Background

Canada has long been a key player in the international extractive industry (mining, oil and gas), with Canadian companies operating in over 100 countries worldwide. The extractive industry is an important contributor to Canada’s economic growth, and has economic, social, and environmental effects on communities across the globe.

Canada has had a Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Strategy in place since the 2009 release of Building the Canadian Advantage: A Corporate Social Responsibility Strategy for the Canadian International Extractive Sector. In 2014, Canada’s initial CSR Strategy was updated and released as Doing Business the Canadian Way: A Strategy to Advance Corporate Social Responsibility in Canada’s Extractive Sector.

Canada’s CSR strategy

Through the Strategy, the Government of Canada sets out its expectation that Canadian extractive sector companies will reflect Canadian values in their operations abroad. The Strategy’s content is grouped into four sets of activities, (hereafter referred to as pillars), to help Canadian companies strengthen their CSR practices and maximize benefits to host countries. These pillars* include:

- Promoting and advancing CSR guidance;

- Fostering networks and partnerships;

- Facilitating dialogue towards dispute resolution; and

- Strengthening the environment affecting responsible business practices.

As stated in the Strategy, its primary audience is the Canadian extractive sector. The Strategy also aims to provide “a more general audience with an overview of Canada’s approach to promoting and advancing CSR abroad.” In addition, the Strategy provides Government of Canada representatives with a “framework to guide their efforts” in the CSR space.

*Refer to Appendix A for a description of the four pillars of the 2014 Strategy and a list of enhancements from the 2009 Strategy.

Implementation

Global Affairs Canada has the overall responsibility for the implementation of the Strategy, and does so in collaboration with Natural Resources Canada.

The Strategy was delivered through the activities undertaken by the following stakeholders:

- Global Affairs Canada;

- Natural Resources Canada;

- Canada’s network of diplomatic missions abroad;

- Canada’s National Contact Point for the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises (MNEs); and

- The Office of the Extractive Sector CSR Counsellor.

Funding

The implementation of the 2014 CSR Strategy was funded by existing departmental resources at Global Affairs Canada and Natural Resources Canada.

Role of Global Affairs Canada

The Responsible Business Practices Division within Global Affairs Canada leads on the implementation of the Strategy. The Division provides operational and policy support to Canada’s Trade Commissioner Service, missions abroad, regional offices, and other divisions on CSR and responsible business conduct more broadly. The Division also houses Canada’s National Contact Point for the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises.

The Natural Resources and Governance Division at Global Affairs Canada also contributes to the implementation of the Strategy by providing guidance in the areas of governance, transparency, shared benefits for communities, and human rights.

Role of Natural Resources Canada

The Lands and Minerals Sector (LMS) at Natural Resources Canada is responsible for CSR-related policy, and for promoting the Strategy through international engagement efforts. LMS works closely with Global Affairs Canada’s Responsible Business Practices Division on mining-related aspects of responsible business conduct.

The Strategic Policy and Innovation Sector contributes to the delivery of the Strategy through its work on promoting transparency in the extractive sector.

The Strategic Petroleum Policy and Investment Office, responsible for the oil and gas sector, did not play a role in the implementation the Strategy over the evaluation reference period.

*Refer to Appendix C for a more detailed description of the roles and resources of both departments.

Evaluation Rationale and Scope

This horizontal evaluation responds to a requirement of the Strategy that it be reviewed five years after its release. The evaluation was conducted by Global Affairs Canada’s Diplomacy, Trade and Corporate Evaluation Division in collaboration with the Evaluation Division at Natural Resources Canada, and in accordance with the Treasury Board Policy on Results.

The purpose of this evaluation was to provide neutral and evidence-based findings, recommendations, and conclusions to senior management on the overall relevance, effectiveness, and coherence of the Strategy and its related tools and resources.

In-scope

The evaluation examined the relevance and effectiveness of the Strategy, and assessed the extent to which it has facilitated and encouraged a coherent approach to corporate social responsibility abroad.

While the CSR Strategy is primarily focused on the extractive sector, uptake and implementation was concentrated on Canadian mining operations abroad. Nevertheless, the Strategy’s relevance and applicability to the oil and gas sector, as well as other sectors, was examined.

Out-of-scope

The Canadian Ombudsperson for Responsible Enterprise (CORE) and the multi-stakeholder Advisory Body on responsible business conduct were established in 2018, after the release of the Strategy. Their mandates and functions were therefore not assessed as part of this evaluation.

The Centre of Excellence was also not assessed as part of the evaluation as the Centre no longer receives consistent Government of Canada funding.

Evaluation reference period: Fiscal year 2014-15 to 2018-19

Terms utilized in this evaluation

This report uses the term “corporate social responsibility” or “CSR” when referring to the Strategy and related expectations, activities, and initiatives as this was the terminology used at the time of the Strategy’s development.

The term “responsible business conduct” or RBC was used when discussing a broader and more inclusive approach, one that better reflects the direction in which both the Government of Canada and Canada’s private sector are heading.

*Refer to Appendix D for expanded definitions of CSR and RBC

Evaluation Questions

Relevance

- Is there an identified and ongoing need for the activities and expectations set out in the four pillars of the CSR Strategy?

Effectiveness

- To what extent is the management and delivery of the Strategy effective?

- To what extent does the Strategy meet its expected outcomes?

Coherence

- To what extent does the Strategy reflect and promote a coherent whole-of-department and whole-of-government approach?

Forward Looking

- If there is a need for a revised CSR Strategy, what changes are necessary?

*Refer to Appendix E for the Strategy’s Logic Model, created by the evaluation team.

Methodology

Through the application of a mixed-methods approach, evaluators collected data from a range of sources to reflect multiple lines of evidence when analyzing data and formulating findings. While examples are used for illustrative purposes throughout the report, each finding was triangulated using evidence from a mix of quantitative and qualitative data. Global Affairs Canada and Natural Resources Canada collaborated on identifying relevant stakeholders throughout the data collection process. Data was collected between February and November 2019. Data collection methods include:

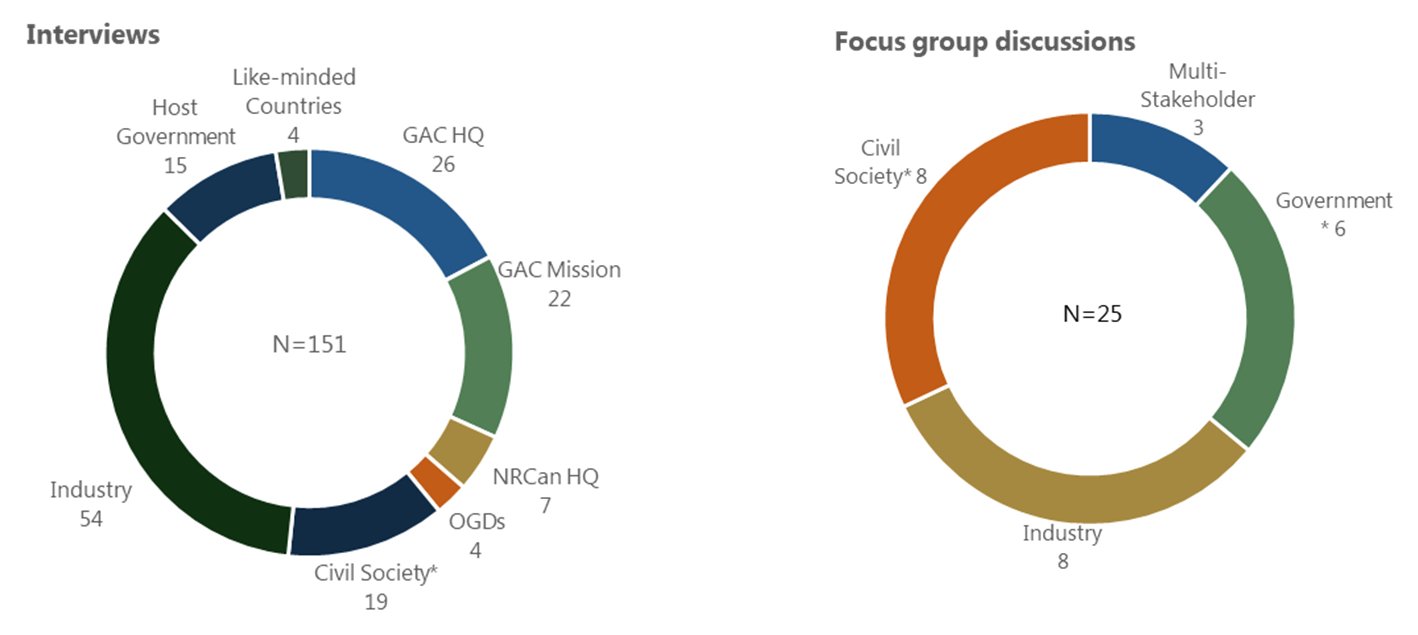

Semi-structured interviews

Individual interviews were conducted with 151 key stakeholders, including internal staff at Global Affairs Canada, Natural Resources Canada, and other relevant government departments and agencies. Interviews were also conducted with external stakeholders, such as industry and civil society representatives.

Literature & document review

Literature related to strategic planning and responsible business conduct was reviewed to examine the relevance and continued need for the Strategy.

Corporate documents, as well as data and reports on activities from Global Affairs Canada and Natural Resources Canada databases were also reviewed.

An analysis of Canadian and international media coverage was conducted to inform the evaluation’s assessment of Canada’s reputation as it relates to issues of responsible business conduct abroad, specifically those related to the extractive sector.

Focus group discussions

A multi-stakeholder focus group discussion was conducted in Toronto to gain in-depth insights on the relevance and effectiveness of the CSR Strategy. Twenty-four additional focus groups were conducted during field visits to gather data on multi-stakeholder perspectives and to encourage dialogue.

Online surveys

An internal survey of Trade Commissioners at Global Affairs Canada with relevant experience with CSR and the extractive sector, generated 139 completed questionnaires with a raw response rate of 30%.

An external survey of Canadian extractive sector companies with operations abroad yielded 112 completed questionnaires, with a raw response rate of 7%.

Case studies

Ten countries were selected for case studies, with field visits conducted in eight and desk reviews conducted for two. Case studies enabled a thorough review of select countries to gain a comprehensive understanding of the context within which Canadian companies operate, as well as the challenges and opportunities faced by all relevant stakeholders, including Canada’s diplomatic staff abroad. Examples of best practices highlighted throughout the report were based only on case studies countries.

*Refer to Appendix F for a more detailed description of the evaluation’s methodology.

Case Studies Map

Text version

Case Studies Map

The following map illustrates the ten countries selected for case studies and the dates field visits were conducted.

Mexico: September 16-20

- Peru: September 30-October 4

- Guatemala: September 9-13

- Colombia: September 23-17

- Democratic Republic of Congo: Desk review

- Serbia & North Macedonia: June 10-13

- Philippines: June 24-28

- Tanzania: Desk review

- Australia: June 17-21

Findings

Finding 1. There is an ongoing need for a Government of Canada strategy on corporate social responsibility abroad.

The development of Canada’s CSR Strategy in 2014 was based on the premise that the extractive industry contributes significantly to Canada’s economic strength, and that Canada remains a key player in the global mining industry. Five years later, the industry continues to occupy an important role in Canada’s economy, with Canadian exploration and mining companies active across the globe.

Canada’s global mining footprint spans multiple countries and vastly different social, environmental, legal, and regulatory environments, many of which are complex and challenging. When coupled with the competitive nature of the industry and the impact it has on local communities and Canada’s reputation writ large, there is an ongoing need for Government of Canada support and guidance in the CSR space.

Canada is home to nearly half of the world’s publicly listed mining and exploration companies, many of which have significant operations abroad. In 2017, roughly 65% of total Canadian mining assets (valued at $168.7 billion) were held abroad by 699 Canadian companies in over 100 countries. This demonstrates the breadth and depth of the global presence of Canadian mining companies. It also calls attention to the impact their operations can have on Canada’s economy and reputation, as well as the economic and social well-being of host communities and countries across the world.

Canadian extractive companies often operate in remote areas abroad, including Indigenous lands and territories, and in communities with widespread poverty, weak governance, and minimal state presence. The complex nature of the extractive industry presents unique CSR-related challenges and opportunities, reinforcing the need for robust support in this area.

While it is widely accepted that extractive sector operations can bring positive change to host communities by catalyzing social and economic development, it is also understood that operations can result in detrimental social and environmental impacts, if not managed responsibly.

Though Canadian extractive sector companies are increasingly adopting CSR practices abroad, a legacy of irresponsible conduct predates them, and conflicts related to their international operations continue to make headlines. A media analysis revealed significant negative media attention in countries where mining-related conflicts had previously taken place, such as Guatemala, the Philippines, and Tanzania.

Corporate social responsibility efforts can minimize potential conflict and help companies secure a social licence to operate. Such efforts can also benefit individual companies by reducing operational, reputational and financial risks, thereby improving productivity and creating investment and branding opportunities.

The ongoing need for a Government of Canada strategy on corporate social responsibility abroad is further illustrated through the evolving responsible business conduct (RBC) landscape. Effective engagement in this space is no longer seen as voluntary or philanthropic.

An international shift away from CSR toward the concept of responsible business conduct has resulted in normative expectations placed on companies to take action to prevent or mitigate adverse impacts, and remedy those that do occur. This shift also means that companies are increasingly expected to incorporate responsible and sustainable policies and practices into their business models and operations.

As the concept of RBC continues to gain prominence and stakeholder demands intensify, Government of Canada support and guidance will be needed for the extractive sector, as well as for other established and emerging markets, such as clean technology, infrastructure, garments, and artificial intelligence.

Overall, the main strength of the Strategy, as identified by interviewees, is its ability to provide outward and public communication that Canada takes CSR seriously. There is an ongoing need for such communication as it is said to give Canadian companies credibility and distinguish them from other foreign-owned companies.

83% of Trade Commissioners surveyed reported an ongoing need for Canada’s CSR Strategy.

64% of Canadian extractive sector companies surveyed identified an ongoing need for the Strategy.

Finding 2. Given the evolving responsible business landscape globally and Canada’s new policies, the CSR Strategy is now outdated.

The evaluation reference period coincided with shifts in Canada’s foreign policy priorities and an evolution of the responsible business conduct landscape. While consistent with some elements of Canada’s new policies, the Strategy does not fully align with the core normative expectations associated with responsible business conduct.

57% of extractive sector companies surveyed endorsed moving the Strategy’s focus beyond the extractive sector.

Five years after its development, Canada’s CSR Strategy remains consistent with some of Canada’s current foreign policy priorities. More specifically, the Strategy is aligned with current core responsibilities set out in the Departmental Results Frameworks of both Global Affairs Canada and Natural Resources Canada. These include:

- Global Affairs Canada’s commitments to expand and strengthen Canada’s global influence, as well as help Canadian exporters and innovators to be successful in their international business development efforts; and

- Natural Resources Canada’s commitment to improve the environmental performance of Canada’s natural resource sectors through innovation and sustainable development, and advance and promote Canada’s natural resources sectors as globally competitive.

At the time of its development, the Strategy, specifically its extractive sector focus, was aligned with Canada’s 2013 Global Markets Action Plan, which advocated economic diplomacy and concentrated efforts on priority sectors, including mining, and oil and gas.

The CSR Strategy also informed the 2014 development of the Canadian Extractive Sector Strategy, which set out a framework for the coherent and effective implementation of efforts aimed at advancing Canada’s extractive sector abroad.

The Strategy is also aligned with various international commitments, referencing such guidelines and tools as the OECD Guidelines for MNEs and the United Nations (UN) Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. Canada’s participation in international fora, such as the Voluntary Principles Initiative further demonstrates this alignment.

While the Strategy specifically promotes CSR, it broadly aligns with the concept of responsible business conduct through references to human rights, Indigenous rights, the environment, and anti-corruption.

This is consistent with several current foreign policy priorities. Notably, responsible business conduct references were found in Canada’s Feminist International Assistance Policy, Global Affairs Canada’s Departmental Sustainable Development Strategy, the 2016 Trade and Investment Strategy, and the 2019 “Canadian Minerals and Metals Plan”, a joint effort between Natural Resources Canada and provincial and territorial governments.

However, Canada’s foreign policy priorities have shifted over the past five years. The Strategy’s focus on the extractive sector does not align with Canada’s 2018 Trade Diversification Strategy, which now sees trade and commercial interests focused on helping Canadian companies access new markets abroad.

The Strategy also does not explicitly emphasize the transformative nature of CSR-related efforts, nor does it reflect such new global objectives as the Sustainable Development Goals, or important international guidelines introduced since 2014. Taken together, the above-referenced shifts and advances mark the Strategy as dated.

2018 marked the announcement of the creation of the Canadian Ombudsperson for Responsible Enterprise (CORE). Though not referenced in the Strategy and thus outside of the scope of this evaluation, the initiative demonstrates Canada`s continued commitment to RBC abroad and reflects Canada's efforts to advance responsible business policies and practices in a way that demonstrates leadership.

*Refer to Appendix C and Considerations for a more detailed description of the Office of the CORE and Appendix B for a timeline of Canada’s approach to RBC Abroad.

Finding 3. The Strategy does not reflect the CSR-related activities undertaken by all government departments and agencies.

The evaluation found that while Global Affairs Canada and Natural Resources Canada are the main delivery agents of the Strategy, there are a number of other government departments and agencies that are also developing CSR-related policies or carrying out CSR-related activities. The CSR Strategy however does not reflect the work of these other government agents, nor does it promote a coherent, whole-of-government approach to CSR. In addition, the evaluation found that the Strategy was delivered in a siloed approach, where CSR-related activities across the government were developed and implemented without clear coordination or alignment.

The 2013 evaluation of Canada’s initial CSR Strategy included a recommendation to “strengthen coordination among government departments”, and highlighted the importance of joint-planning and coordination of activities. While the 2014 Strategy indicates that Global Affairs Canada will work closely with other government departments, namely Natural Resources Canada and Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada, this evaluation found no whole-of-government approach in place to align all activities undertaken to promote CSR.

Without a whole-of-government approach, both internal and external stakeholders described Canada’s approach to CSR as disjointed, with multiple departments and agencies undertaking various initiatives without clear coordination or alignment.

Internal and external stakeholders suggested Canada develop and implement a National Action Plan on Business and Human Rights to help bring policy coherence on CSR and demonstrate its commitment to the UN Guiding Principles.

Global Affairs Canada commissioned a study of the feasibility of developing a National Action Plan in 2016, and found “limited policy coherence and no shared human rights vision among federal, provincial, and territorial governments.” The study found that government departments and agencies use different CSR standards and guidelines and develop their activities based on “varying degrees of understanding of the intent of the [UN Guiding Principles].” Nonetheless the study stated that existing policies, laws, mandates and government practices provided an opportunity for closer alignment in CSR programming.

Despite the potential for greater alignment, the evaluation did not find evidence of the development of a holistic approach for CSR. However, the evaluation found evidence that Global Affairs Canada, in an effort to foster collaboration, tracked the work of other government departments and agencies on broader CSR-related issues. Though, staff recognized a need for enhanced engagement more broadly.

Role of other government departments and agencies in promoting CSR

Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC)

ESDC does not have a current role in the implementation of the Strategy. However, the department is leading the review of possible supply chain legislation and has included Global Affairs Canada and other departments in the consultation process. Interviewees explained that potential supply chain legislation will have a large impact on Canadian companies operating abroad. ESDC also commissioned a study in 2019 examining CSR policy opportunities domestically, demonstrating their intention of working collaboratively on responsible business conduct across the country.

Export Development Canada (EDC)

EDC has recently updated and implemented policies and frameworks related to responsible business conduct, namely its Human Rights Policy and Environmental and Social Risk Policy. EDC’s practice is aligned with the expectations and standards promoted in the CSR Strategy.

Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada (ISED)

Following the release of the 2009 Strategy, ISED, formerly Industry Canada, actively promoted CSR through the development and dissemination of tools and guidance. However, evidence revealed that the department is no longer actively engaged due to restructuring and a change in priorities, despite being mentioned as a delivery agent in the Strategy.

Finding 4. The Government of Canada's CSR-related efforts have contributed to Canada's reputation as a convenor of multi-stakeholder dialogue.

The Strategy identifies fostering networks and partnerships as a key component of Canada's comprehensive approach to CSR abroad. Since the development of the Strategy, the Government of Canada has stepped up efforts to support constructive engagement between Canadian companies, local communities, civil society, and host governments at all levels. This has contributed to Canada's reputation as an honest broker and convenor of multi-stakeholder dialogue abroad.

The benefits of Canada's role as convenor of multi-stakeholder dialogue are numerous and far-reaching. In particular, this has contributed to an increased visibility of Canada's approach to CSR, reinforced Canada's reputation as an honest broker, and has provided neutral, secure, and constructive fora for dialogue and bridge-building between affected stakeholder groups.

The evaluation found that missions across geographic regions have proactively addressed potential conflicts and pressing CSR-related issues through multi-stakeholder engagement. An analysis of Global Affairs Canada's CSR initiative reports revealed that recurring topics discussed in multi-stakeholder forums over the past five years included:

- Anti-corruption;

- Artisanal and small scale mining;

- Indigenous relations;

- Transparency;

- Value chains; and

- Women's economic empowerment.

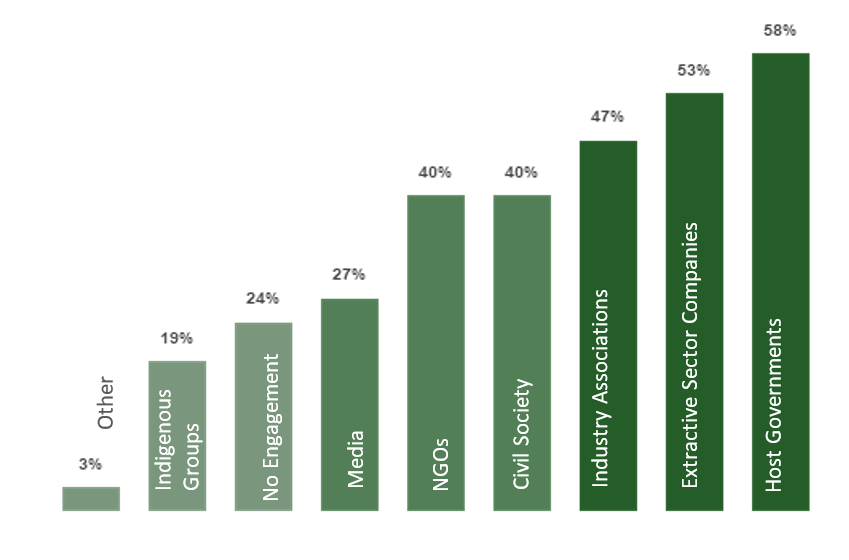

The analysis also revealed that the stakeholder groups with the highest participation rates included extractive sector companies, industry associations and host government representatives. Local communities and Indigenous groups, whose participation is widely perceived across interviewees as critical to effective multi-stakeholder engagement, participated at significantly lower rates. This was corroborated by survey data and field visit observations, and was identified as a gap in Canada's convenor role. According to Global Affairs Canada staff, this gap stems from missions lacking the financial resources needed to bring stakeholders from remote areas to capital cities, which is where most initiatives take place.

Level of Trade Commissioner engagement on CSR-related initiatives by stakeholder group (%) (2014-15 to 2018-19)

Text version

The graph depicts the level of Trade Commissioner engagement with various stakeholder groups on CSR-related initiatives as a percentage, from 2014-15 to 2018-19.

- Other: 3%

- Indigenous Groups: 19%

- No Engagement: 24%

- Media: 27%

- NGOs: 40%

- Civil Society: 40%

- Industry Associations: 47%

- Extractive Sector Companies: 53%

- Host Governments: 58%

Nevertheless, interviewees across stakeholder groups commended the Government of Canada for convening stakeholders who are often polarized by different views and perspectives, and who may not otherwise have access to one another. In addition to providing a safe and neutral space for dialogue, Canada's efforts are said to foster networks and partnerships across stakeholder groups. They also have the potential to facilitate the sharing of best practices, challenges, and lessons learned, though interviewees noted that efforts in this area require increased uptake.

The evaluation found a strong interest in an increased sharing of best practices across the extractive sector. Events hosted by the Government of Canada on the margins of trade shows and conventions such Investing in African Mining Indaba and Prospectors and Developers Association of Canada’s annual convention, have provided opportunities for further networking and the discussion of CSR. Industry representatives, through roundtable discussions, underscored their interest in learning from one another’s experiences and stated their confidence in the Government of Canada’s ability to provide venues to do so.

Interviewees across stakeholder groups discussed the potential benefits of opening such venues to all affected stakeholder groups, citing this as an opportunity to change the negative narrative that surrounds extractive sector projects and highlight the sector’s potential for generating positive impacts.

While the Government of Canada, through the Strategy, committed to helping share effective practices across the extractive industry, efforts are not felt to have sufficiently delivered on this commitment.

The Government of Canada’s efforts to convene stakeholders and foster networks and partnerships are not unique to Canada’s network of missions abroad. Global Affairs Canada and Natural Resources Canada, through staff at headquarters and regional offices, have also been integral to Canada’s convenor role.

Global Affairs Canada’s Responsible Business Practices Division engages in various multi-stakeholder forums, including the Devonshire Initiative, which regularly convenes industry and civil society stakeholders with the aim of improving development outcomes in the mining context.

The Division has also created such initiatives as the CSR Speaker Series, which invites expert speakers to educate interested parties on responsible business conduct. Through the Series, ten events have taken place in Canada throughout the evaluation reference period on topics including stakeholder engagement, governance in the extractive sector, business and human rights, and local procurement.

Furthermore, Global Affairs Canada’s Natural Resources and Governance Division and Natural Resources Canada have both engaged, often jointly, in multilateral dialogue to advance international standards, best practices, and improved performance by all stakeholders in the natural resource sector. A notable example is their work on transparency through such initiatives as the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI).

48% of extractive sector companies surveyed think Canada’s diplomatic staff have helped strengthen relationship between the companies and local/host governments.

Diplomatic staff were least likely to strengthen relationships between industry and the following stakeholder groups: CSR consultants, local communities and subject matter experts.

Mission efforts to convene dialogue, and foster networks and partnerships

Tanzania

The High Commission of Canada in Tanzania, in collaboration with a civil society policy forum and private sector foundation, organized a CSR Forum in 2019 with an exclusive focus on women’s empowerment. This partnership facilitated the sharing of experiences and drew on the depth of these organizations’ networks to reach a wider audience and foster relations across stakeholder groups.

Serbia & North Macedonia

In 2018, the Embassy of Canada to Serbia organized a panel on CSR best practices in North Macedonia that focused on the importance of trilateral dialogue (government, private sector and civil sector). The event successfully provided Canadian companies with a venue to engage with host government representatives and other local stakeholders to discuss the future development of projects. This resulted in stronger relationships between affected stakeholders.

Finding 5. The Government of Canada has contributed to a strengthened environment for responsible business practices through bilateral and multilateral efforts.

Through the Strategy, the Government of Canada committed to strengthening the environment affecting responsible business practices abroad. The Government of Canada’s bilateral and multilateral efforts in this area have contributed to a more stable, transparent and predictable investment environment. This has been achieved through the promotion of relevant standards, guidelines, and best practices, as well as through bilateral capacity-building initiatives and international assistance programming in regions with significant Canadian extractive operations.

58% of extractive sector survey respondents agreed that Canada’s contributions abroad are strengthening the local institutional capacity in responsible resource management.

Canada’s efforts to strengthen the environment affecting responsible business practices were broadly understood across stakeholders to facilitate investment, improve Canada’s reputation abroad, and reinforce commitments in other priority areas, such as the promotion of human rights. By addressing such issues as corruption and natural resource governance in host countries, the Government of Canada’s efforts have contributed to a climate that is more conducive to responsible business conduct and sustainable development.

Bilateral engagement

The Government of Canada has various measures in place to enhance the CSR-related performance of Canadian companies and positively impact the extent to which local communities and host governments benefit from their contributions.

One of these measures is the inclusion of provisions for CSR in all Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) signed since August 1, 2009, as well as most Foreign Investment Promotion and Protection Agreements (FIPAs) signed since 2010. These provisions suggest that signatory countries encourage companies operating in their territories, or subject to their jurisdiction, to voluntarily incorporate internationally recognized CSR standards into their operations.

Additionally, Canada’s Trade Commissioner Service introduced Integrity Declarations for clients in 2014. Upon signing an Integrity Declaration, Canadian companies attest that they understand the Government of Canada’s ethical expectations, and that they will not engage in corrupt or illegal activities. As of March, 2020, 1574 Integrity Declarations were in place globally.

The Government of Canada has also worked with host governments to enhance their capacity to manage their own natural resources in an economically, socially, and environmentally sustainable manner. Natural Resources Canada has played an integral role in this regard through its provision of technical knowledge and expertise to mining-rich countries. Interviewees, particularly host government officials, noted several examples of bilateral support from Natural Resources Canada, some referencing Memoranda of Understanding between the department and host country ministries on mining and natural resources.

International assistance programming

Through Canada’s official development assistance (ODA), Global Affairs Canada supports developing countries’ efforts to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals by promoting sound governance of natural resources. Between 2014 and 2019, Canada supported more than forty projects aimed at improving natural resource governance, including projects with multilateral institutions, such as the World Bank and the Inter-American Development Bank, that were fully disbursed by Global Affairs Canada and implemented through development partner agencies. Global Affairs Canada’s internal evaluation of this programming in 2018 found that it increased transparency, thereby improving legal and regulatory frameworks and fostering broader engagement at the community level.

A notable example of such programming is Canada’s support for the “Building Responsible Mineral Supply Chains for Development in Africa” project in the Democratic Republic of Congo. The project aims to empower those working in artisanal mining and ensure that high-value minerals do not fuel conflict and instead contribute to sustainable development.

Pursuant to the launch of Canada’s Feminist International Assistance Policy in 2017, natural resource programming now places greater emphasis on addressing barriers that prevent women and marginalized groups from benefiting from natural resources and from taking part in decisions as to how they are used.

Multilateral engagement

The Government of Canada engages multilaterally to advance international standards and best practices, and promote transparency and accountability in the international extractive sector. Canada promotes responsible business conduct in multilateral fora, including:

- The OECD;

- the Organization of America States;

- La Francophonie;

- The Commonwealth;

- The Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation; and

- The Group of Seven (G7).

The Government of Canada also engages in a number of multilateral initiatives to foster leadership in social, environmental and economic performance by the extractive sector. Notably, Canada promotes the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) as a Board member and supporting country. Canada’s efforts have contributed to transparency and improved governance of the extractive sector in several countries around the world.

Canada also served as chair for the Voluntary Principles on Security and Human Rights Initiative in 2016-17 and hosted the Annual Plenary Meeting in 2017. Canada, through its participation in the Initiative, has, among other accomplishments, promoted human rights in extractive sector projects.

Additionally, the Government of Canada provides core funding to the Intergovernmental Forum on Mining, Minerals, Metals and Sustainable Development, through which countries benefit from technical assistance and training on leveraging mineral wealth to reduce poverty and pursue sustainable growth.

Canada also participated in the development of the “OECD Due Diligence Guidance on Responsible Mineral Supply Chains from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas” through its provision of recommendations to help companies respect human rights and avoid contributing to conflict through their mineral purchasing decisions and practices.

Finally, through the Extractive Sector Transparency Measures Act, Canada contributes to global efforts to increase transparency and deter corruption in the extractive sector. This is achieved by requiring certain extractive entities that are subject to Canadian law to publicly disclose, on an annual basis, specific payments made to all governments both within Canada and abroad.

73% of Trade Commissioners surveyed agreed that Canada’s contributions abroad are strengthening local institutional capacity in responsible resource management.

Highlights of Canada’s international contributions

- In 2019, Canada, alongside like-minded nations and groups, paved the way for new EITI implementation requirements regarding Gender and Environmental reporting. Canada’s involvement with the EITI has placed it at the forefront of open data, and environmental and gender inclusiveness reforms within the Initiative and abroad.

- During Canada’s 2018-19 tenure as the Open Government Partnership (OGP) Co-Chair, Canada contributed to developing a vision of: Inclusion, Participation, and Impact. In 2019, Canada hosted the annual OGP Global Summit in Ottawa. This event involved government departments (including Global Affairs Canada and Natural Resources Canada), international governments, the EITI, global civil society organizations, and academia. The event promoted open data policies, as well as the implementation of open government commitments that aim to help combat corruption, enable the utilization of new technologies, strengthen governance, and empower citizens.

- Canada co-organized sessions focused on gender equality at the 12th and 13th OECD Forums on Responsible Mineral Supply Chains, and contributed to the drafting of the Stakeholder Statement on Implementing Gender-Responsive Due Diligence and ensuring the human rights of women in Mineral Supply Chains.

Finding 6. The voluntary dispute resolution mechanisms outlined in the Strategy were largely ineffective.

In an effort to facilitate dialogue toward dispute resolution, the 2014 CSR Strategy outlines two non-judicial mechanisms: the Extractive Sector CSR Counsellor, which is no longer active, and the Canadian National Contact Point (NCP) for the OECD Guidelines for MNEs. Both mechanisms aim to bring parties together to find mutually-beneficial solutions in cases of conflict. While both the CSR Counsellor and NCP have engaged in various outreach activities, the evaluation found that stakeholders did not frequently access the mechanisms due to a lack of awareness and/or perceived ineffectiveness.

Percentage of Trade Commissioners surveyed that accessed the following mechanisms:

27% - CSR Counsellor

15% - Canada’s NCP

Percentage of extractive sector companies surveyed that accessed the following mechanisms:

11% - CSR Counsellor

5% - Canada’s NCP

| Extractive Sector CSR Counsellor | Canada’s National Contact Point | |

|---|---|---|

| Mandates of Canada’s National Contact Point and the Extractive Sector CSR Counsellor overlapped in some areas, namely the promotion of the OECD Guidelines for MNEs, and the contribution to dispute resolution between extractive sector companies and other stakeholders. This overlap denotes a potential for duplication of efforts. | Canada established the Office for the Extractive Sector CSR Counsellor in 2009 with a mandate to advise stakeholders on the implementation of guidelines, as well as to review CSR practices of Canadian extractive sector companies operating abroad. The Strategy shifted the Counsellor’s focus to a more proactive, preventative, and early-detection approach rather than reviewing allegations. The Office has since closed in May 2018. | Canada established the NCP in 2000 as a requirement for countries adhering to the OECD Guidelines for MNEs. The NCP’s mandate is to raise awareness of the Guidelines, as well as contribute to the resolution of issues stemming from the implementation of the Guidelines. A notable difference with the CSR Counsellor is that the NCP’s mandate extends beyond the extractive sector to all sectors. |

| Both the CSR Counsellor and NCP were dependent on Global Affairs Canada for resources, including financial and human resources, as well as equipment and accommodation. This impacted the ability of both mechanisms to be perceived as independent or neutral. | Global Affairs Canada staff stated that the Counsellor’s Office was under-staffed, with only three full-time employees, and under-resourced. The Office did not have a dedicated funding source and depended on Global Affairs Canada for its budget. Former staff interviewed believed that this affected engagement with important stakeholders such as SMEs, as well as the timely publication of reports as mandated. | Evidence revealed challenges with the NCP in balancing activities with an unpredictable number and nature of cases to review. While the NCP committee includes seven departments, only Global Affairs Canada and Natural Resources Canada have dedicated resources. The NCP Secretariat is currently comprised of two full-time employees and is expected to cover all sectors. The number of cases received for review may impact the ability of the NCP Secretariat to respond to all requests in a timely manner. |

| Over the evaluation period, the NCP and former CSR Counsellor participated in a number of outreach activities both nationally and internationally to raise awareness about CSR guidelines and focus on key issues such as due diligence in supply chains. | Between 2015 and 2018, the CSR Counsellor participated in 34 national and international events to present his role, discuss CSR-related issues, and promote guidance and tools to multiple stakeholders. Outreach activities were concentrated in a select few regions including Canada, Latin America, and Sub-Saharan Africa to a lesser extent. While the Counsellor met with a wide range of stakeholders, many interviewees reported being dissatisfied with the Counsellor due to a lack of ongoing engagement and follow-through. | The NCP held annual multi-stakeholder information sessions and participated in over 48 outreach events in Canada and abroad since 2014. Targeted audiences included representatives from industry, government, non-governmental organizations, labour groups, and academia. Despite the outreach efforts, evidence demonstrates that civil society in particular were unaware of the potential benefits of using the NCP’s procedure for specific instances. |

| Between 2014 and 2018, the CSR Counsellor and NCP received few requests for review of Canadian company operations. This is in light of a number of allegations of human rights abuses brought against Canadian companies operating abroad, some of which were reviewed by Canadian courts. Private sector and civil society stakeholders stated that obtaining access to the dispute resolution mechanisms was a barrier to submitting requests for review. | The CSR Counsellor did not formally review any cases between 2015 and 2018. Taking a preventative and proactive approach, staff stated the Office was involved in informal mediation where disputes were resolved behind closed doors. These meetings were not documented and could not be verified by the evaluation team. In addition, civil society stakeholders did not see the Counsellor as a neutral figure to mediate issues and questioned his capacity to provide effective remedy for victims. | Canada’s NCP reviewed 8 specific cases since 2014, with one resulting in a recommendation for the withdrawal of trade advocacy services. The evaluation found that civil society stakeholders questioned the impartiality of the mechanism based on its placement within an international trade promotion unit at Global Affairs Canada. This perception, coupled with the lengthy and unpredictable process for review, may be associated with the low number of requests for review received by the NCP. |

The 2014 Strategy provided both the CSR Counsellor and the NCP with the ability to recommend trade measures, including the withdrawal of trade advocacy services or future financing from Export Development Canada. While this was seen as a powerful tool, the evaluation found that these measures were perceived as only pertinent for those companies that want or need trade advocacy support or financing. These measures were considered useful for bringing industry to the mediation table, but were not seen as an effective tool to compel all companies to align with the Strategy’s values. In addition, they lacked clarity on how the trade measures could be applied to companies as standard operating procedures were only developed in 2019.

58% of extractive sector respondents were not aware of the potential trade measures for non-participation in the dialogue facilitation process of the available dispute resolution mechanisms.

43% of Trade Commissioners surveyed cautioned their clients regarding potential trade measures.

Finding 7. Despite concerted efforts to promote and advance CSR guidance, gaps were noted in outreach to key stakeholder groups.

An integral part of the CSR Strategy is the promotion of CSR guidance, with the aim of companies adopting CSR best practices in their operations abroad. The evaluation found that while there was evidence of companies integrating CSR in their operations, the uptake was concentrated to larger, more established extractive sector companies.

66% of extractive sector companies surveyed have a CSR Policy in place.

54% have publicly stated human rights commitments.

The importance of promoting and advancing CSR guidance to companies operating abroad is paramount and serves to promote the “Canadian way” of doing business. Canadian exploration, mining, and supply and service firms are often the face of Canada abroad. How they operate determines the success of projects, as well as outcomes for communities. Success in this regard requires early and consistent steps to minimize and mitigate adverse effects on local communities and the environment.

Taking this into account, the Government of Canada promotes and advances CSR guidance through the Strategy itself, as well as through activities undertaken in Canada and abroad. Such activities included engagement to help develop and promote guidance, the creation and dissemination of tools, the sharing of best practices, and the hosting of events and workshops.

The evaluation found that larger, more established extractive sector companies were broadly familiar with Canada’s approach to CSR, demonstrating that outreach by the Government of Canada to this stakeholder group was fairly effective.

More specifically, established companies were familiar with the tools promoted through the Strategy, the CSR events hosted by missions, and Global Affairs Canada’s programming on sustainable natural resource development. In addition, the majority of extractive sector companies interviewed and surveyed recognized the importance of CSR and have instituted CSR policies and practices within their operations abroad. The most common reasons cited for involvement in CSR were:

- Securing community support for operations;

- Moral and ethical obligations to conduct business responsibly; and

- Enhancing the company’s reputation.

76% of extractive sector companies surveyed are involved in CSR initiatives in their operations abroad.

Conversely, the evaluation found that small and medium enterprises (SMEs), in particular exploration companies, have little familiarity with the Strategy and low levels of CSR adoption in their operations abroad. This stakeholder group noted difficulties in deciphering whether the Strategy was applicable to them and how they could ensure compliance in their operations.

A survey of extractive sector companies uncovered a lack of internal expertise and capacity, as well as financial costs associated with CSR-related efforts, as factors preventing companies from becoming involved with CSR. Interviews and roundtable discussions presented leadership and corporate culture as additional external factors affecting companies’ overall adoption of CSR practices.

Despite the Government of Canada’s numerous activities to promote and advance CSR guidance, internal and external stakeholders suggested that there was insufficient outreach and communication of the Strategy and Government of Canada expectations to all relevant stakeholder groups, namely SMEs and companies outside of the extractive sector.

Mission staff identified a number of factors affecting their ability to engage with stakeholders in need of advice and guidance on CSR. Factors included: the eligibility of a company as a client of Canada’s Trade Commissioner Service, an ambiguous understanding of whether a company is defined as “Canadian”, the availability of staff, competing priorities, and the availability of necessary training and tools.

Finding 8. The tools and resources promoted through the Strategy were sufficient, though not widely accessed.

A variety of external-facing tools and resources have been developed by various Government of Canada departments and agencies to guide and support Canadian companies in their efforts to implement the Strategy abroad. Though widely-perceived as relevant to the needs of extractive sector companies abroad, they were not easily accessible. The evaluation found that tools and resources developed by industry associations and international organizations were more frequently consulted and used abroad than those developed by the Government of Canada.

Similarly, considerable effort has gone into the development of tools, training, and resources for the Strategy’s primary delivery agents – notably, staff at Global Affairs Canada. Though available, the tools were perceived as trade-focused and lacked adaptability to challenging host country contexts.

External-facing tools and resources

The Strategy promotes and advances a number of international guidelines and outlines the Government’s expectation that Canadian companies will “meet or exceed widely-recognized international standards for responsible business conduct”. In an effort to assist Canadian companies in this regard, a number of tools and resources have been developed by both the Government of Canada and Canadian industry associations. The evaluation found that though intended to guide mining, and oil and gas companies in their operations abroad, available tools and resources were predominately focused on Canadian mining companies.

There was a general consensus amongst industry and stakeholder representatives that the number of tools currently available to promote CSR was sufficient, and that efforts should be concentrated on making existing tools more accessible and adaptable to host country contexts, rather than on developing additional resources.

The evaluation found that government-developed tools and resources were not widely-accessed by industry representatives. This was largely seen as the result of untargeted outreach strategies and inadequate information technology platforms. Interviewees across stakeholder groups noted that Government of Canada tools are not located in a single, coherent repository, which has impeded some companies’ ability to access and use them.

According to interviewees, the most frequently used tools were those developed by Canadian industry associations – namely, the Mining Association of Canada’s Towards Sustainable Mining (TSM) and Prospectors and Developers Association of Canada’s e3Plus.

A survey of extractive sector companies indicated that these industry-developed tools (TSM and e3Plus) had been used by 49% and 35% of respondents, respectively.

Among the tools developed by the Government of Canada, the following were found to be the most frequently used abroad:

- Global Affairs Canada’s series of CSR/RBC Snapshots for Companies;

- Natural Resources Canada’s “Exploration and Mining Guide for Aboriginal Communities”;

- Natural Resources Canada’s “CSR Checklist for Canadian Mining Companies Working Abroad”; and

- The former-CSR Counsellor’s “CSR Standards Navigation Tool”.

67% of extractive sector companies surveyed found Canadian-developed tools and resources were relevant to their operations abroad.

59% found these tools useful.

Internal-facing tools and resources

Trade Commissioners were generally aware that tools, resources, and training opportunities had been developed to assist with the delivery of the Strategy. However, newer Trade Commissioners reported a stronger familiarity and were more inclined to cite them as useful.

Though available to all staff, resources were perceived as being trade-focused and less relevant to the priorities of other business lines at Global Affairs Canada, namely diplomacy and international assistance. Given the Strategy’s commitment to increased support for all mission staff, interviewees felt that more effort was needed to develop tools and training sessions that explicitly link the Strategy to the work of all implicated business lines.

Global Affairs Canada’s Voices at Risk: Canada’s Guidelines on Supporting Human Rights Defenders was seen as an important contribution to the diplomacy stream, and to guidance on responsible business conduct writ large. Though this was noted as an important starting point, staff across business lines highlighted a pressing need for cross-stream tools, training, and guidance on the effective handling of issues of business and human rights.

Finally, staff reported issues with the generality of the Strategy and its associated tools, resources, and training. In particular, they reported difficulties in adapting existing tools and training materials to individual host country contexts, emphasizing the complex and challenging nature of both the industry and the regions in which extractive operations typically occur.

Survey and interview data demonstrated an appetite for additional training opportunities, including:

- Host country context-specific training;

- Training on thematic issues;

- Training on business and human rights;

- Scenarios and case study learning;

- In-person, on the ground field training;

- The sharing of best practices; and

- Regional and cross-stream training opportunities.

Examples of adapted tools and resources

Field visits and interviews revealed several innovative ways in which Canadian resources have been adapted to suit host country contexts.

Global Affairs Canada (Headquarters)

Mission staff are not CSR experts, nor are they subject matter experts on local customs and deep-rooted mining-related issues. Global Affairs Canada’s Responsible Business Practices Division has prepared country-level briefings and organized one-on-one training sessions for incoming Trade Commissioners in key extractive markets (America and Latin America) to equip them with the information necessary to engage in the CSR space.

Peru

In 2018, the Canadian Embassy in Peru, in collaboration with Peru’s Ministry of Energy and Mines and a Canadian consultant, developed the “Communication and Relations Toolkit for Responsible Mining Exploration”, which promotes best practices and covers responsible governance, ethics, gender, and Indigenous rights. The Toolkit is available in Spanish and pamphlets were translated into two Indigenous languages (Quechua and Aymara).

55% of Trade Commissioners surveyed agreed that staff have the necessary tools to engage in CSR-related matters.

59% agree they know which tools or resources to consult when complex CSR-related issues arise.

Finding 9. The CSR Fund provided missions with a valuable resource to help deliver the Strategy abroad.

The CSR Fund has been operational since 2009 and is available to Trade Commissioners at missions to assist with the implementation of the Strategy. Between 2014-15 and 2018-19, the Fund financed approximately 205 initiatives in 52 countries. Initiatives varied across missions and included workshops, roundtables, annual forums, and the development and dissemination of information products. The evaluation found the CSR Fund to be the primary and most practical resource used by Trade Commissioners to help deliver the Strategy abroad.

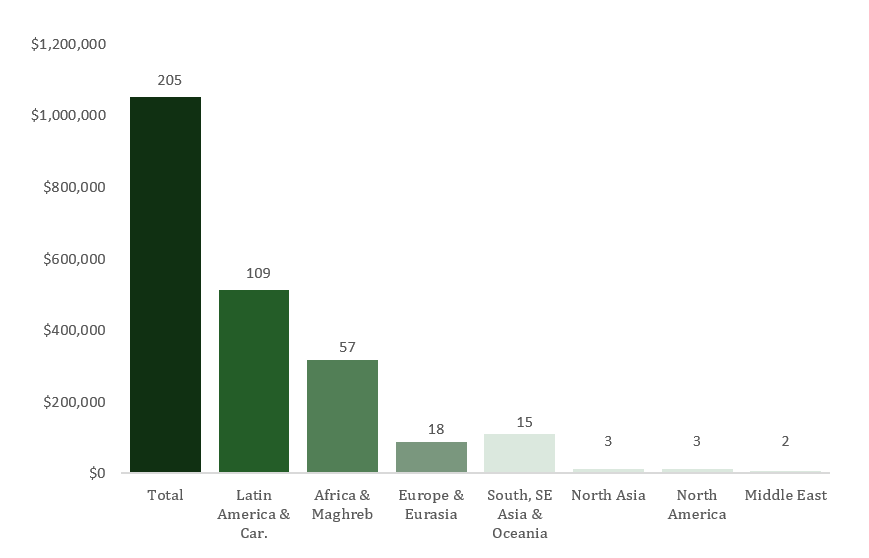

CSR Fund actuals and number of initiatives across the regions (2014-15 to 2018-19)

Text version

The graph represents the actual expenditures of the CSR Fund and number of initiatives funded across the various regions from 2014-15 to 2018-19.

CSR Fund Actuals ($)

- Total: $1,050,000.93

- Latin America & Caribbean: $512,998.43

- Africa & Maghreb: $316,680.41

- Europe & Eurasia: $87,307.77

- South, Southeast Asia & Oceania: $109,013.60

- North Asia: $12,730.16

- North America: $11,270.56

- Middle East: $5,694.28

Number of initiatives financed by the CSR Fund

- Total: 205

- Latin America & Caribbean: 109

- Africa & Maghreb: 57

- Europe & Eurasia: 18

- South, Southeast Asia & Oceania: 15

- North Asia: 3

- North America: 3

- Middle East: 2

The CSR Fund, which is part of Global Affairs Canada’s Integrative Trade Strategy Fund envelope, is a dedicated annual fund of $250,000 that is provided to missions through the Trade Commissioner Service. The CSR Fund covers initiatives under four main areas:

1) Stakeholder Engagement;

2) Risk Mitigation;

3) Environmental Stewardship; and

4) Advancing CSR Standards.

The Fund was predominately distributed to missions in regions with significant Canadian mining assets and challenging social and environmental conditions. Missions in Latin America and the Caribbean benefitted most from the CSR Fund, accounting for 52% of all initiatives funded over the evaluation reference period. Missions in Sub-Saharan Africa and the Maghreb were the second most common users of the Fund. This concentration of the use of the CSR Fund demonstrates that CSR is a priority for Trade Commissioners in these regions.

A survey of Trade Commissioners revealed that only 38% of respondents applied for the CSR Fund over the past five years. Survey respondents cited strong local laws in host countries and the extractive sector not being a priority as reasons why CSR-related activities were not organized at their respective missions.

To ensure the alignment of initiatives with the CSR Strategy, the Responsible Business Practices Division at Global Affairs Canada, charged with the management of the CSR Fund, provided guidance and feedback to Trade Commissioners applying for the Fund. The evaluation found that the Division was engaged throughout the application and disbursement process, and that they had provided quality feedback to Trade Commissioners on how to strengthen initiatives and effectively apply for funding.

86% of Trade Commissioners surveyed that applied for the CSR Fund found it to be very useful in meeting objectives.

While the CSR Fund was widely credited as a useful resource to undertake initiatives at mission, Trade Commissioners identified a few shortcomings. For example, Fund guidelines limit spending on hospitality to a maximum of 10% of total allocation, which may be insufficient to conduct greater outreach to stakeholders located in remote areas. In response to this shortcoming, staff acknowledged that identifying CSR as a mission priority and collaborating with colleagues from other business lines to leverage funds, as key to achieving greater outreach.

Despite the challenges identified, the CSR Fund disbursed over $1 million over the evaluation reference period. An analysis of initiatives in case study countries revealed a number of key results such as:

- Raising awareness of issues relevant to the region such as artisanal mining, value chains, gender equity, and youth employment;

- Formation of partnerships between stakeholders on the margin of events; and

- Showcasing Canada as a leader in responsible business conduct through promotion of the Strategy and sharing of best practices.

Finding 10. A whole-of-mission approach contributed to the effective delivery of the Strategy at the country level.

The evaluation found that Trade Commissioners occupy an essential and indisputable role in the Strategy’s delivery. It also found that CSR-related issues are relevant to the mandates and expertise of other business lines present at missions abroad– namely, diplomacy and international assistance.

Despite various challenges impeding their efforts, mission staff across geographic regions have made concerted efforts to approach CSR as a whole-of-mission endeavour. Interviewees cited this as crucial to a holistic understanding of CSR-related issues and access to the various affected stakeholder groups. Such an approach was also said to help ensure efforts are coordinated and do not work at cross-purposes.

The CSR Strategy identified mission staff, particularly Trade Commissioners, as its primary delivery agents. Mission staff are well-placed to employ this role, with staff dedicated to managing diplomatic relations, promoting international trade, and leading on Canada’s international assistance efforts across the globe.

Corporate social responsibility cuts across the work of Global Affairs Canada’s trade, diplomacy, and international assistance business lines. The evaluation found that effective CSR-related efforts necessitate an integrated approach that incorporates the knowledge, expertise, and networks of all three business lines. Mission staff reported that collaboration, as well regular cross-stream updates on relevant programs and initiatives, contributes to mutually reinforcing outcomes in the CSR space and helps ensure that efforts are not working at cross-purposes.

While the Strategy elaborates on the vital role of Trade Commissioners for its implementation, there is ambiguity surrounding the roles of other business lines, as well as on how efforts should be integrated in practice. Consequently, delivery of the Strategy was widely perceived as being a function of Trade Commissioners, despite certain aspects being more closely aligned with the expertise of diplomacy and international assistance. In particular, interviewees suggested that other business lines may be better equipped than Trade Commissioners to advise on environmental and social risks, including those related to human rights.

Overall, the evaluation found that missions were making concerted efforts to engage in CSR-related initiatives through an integrated whole-of-mission approach. Nevertheless, a number of challenges were said to impede their ability to consistently adopt such an approach, including:

- Differing mandates, priorities and beneficiaries;

- Misaligned departmental tools and processes;

- A lack of familiarity with business line-specific initiatives across the mission; and

- A lack of management level buy-in.

Despite these challenges, an analysis of CSR initiatives demonstrated that many missions were coordinating efforts by sharing contacts and expanding networks, co-organizing events, consulting on the design of CSR tools, and leveraging funds where possible.

Examples of a whole-of-mission approach to CSR

Colombia

In 2018, the Embassy of Canada to Colombia established a cross-stream committee to break down silos and foster synergies on CSR-related issues. The committee is said to provide mission staff with a more holistic understanding of relevant issues, such as Indigenous consultations, gender equity, anti-corruption, transparency, and human rights.

Through the services of a CSR expert, the mission also developed a “Responsible Business Conduct Roadmap” to identify the mission’s CSR-related objectives and link them to relevant Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The document also clarifies the roles of the Head of Mission, Trade Commissioners, and diplomacy and international assistance officers as they relate to responsible business conduct in Colombia.

Guatemala

Over the past five years, the Embassy of Canada to Guatemala has undertaken a number of activities aimed at driving the CSR agenda forward by addressing complex issues. One of the main factors of success behind these CSR events is the mission’s joint staff approach, whereby the commercial, diplomacy and international assistance sections jointly plan and execute initiatives. This multi-disciplinary approach allows for wider outreach as well as a pooling of resources to accomplish goals.

Finding 11. The CSR Strategy’s design is missing a number of key components, impacting its overall effectiveness.

Key components of a strategy

Text version

The diagram depicts the key components that should be included in a strategy. The circle in the centre represents the strategy. The five arrows surrounding circle and pointing inward represent the key components: Diagnosis, Approach, Objectives, Expectation, and Target Audience.

Literature defines a strategy as a framework for decision-making that helps establish actions to address a particular challenge. The CSR Strategy was designed without a number of key components to make it a strong strategy. Instead, it reads as a high-level document that provides a set of expectations and important considerations. The design of the Strategy has impacted how it is read, understood, and applied.

The 2014 CSR Strategy does not sufficiently include, as part of its design, the five key components of a strategy as outlined in literature.

The Strategy lacks an adequate diagnosis of why the Strategy is needed. An analysis of the nature of the challenges and the obstacles to overcome is not presented. The Strategy therefore cannot effectively provide a framework to address a problem, because it has not defined the problem.

Another component missing from the Strategy is an explanation of the approach Canada has chosen to promote CSR. A detailed rationale that rules out other possible actions can help the audience better understand the method chosen. In particular, the CSR Strategy does not clearly articulate the nature of Canada’s mixed voluntary and mandatory approach to CSR, which has generated confusion for Canadian companies as well as other stakeholders over expectations and accountability. There is also uncertainty surrounding the Government of Canada’s role in monitoring the conduct of Canadian companies operating abroad.

The Strategy also does not clearly articulate its vision, mission and overall objectives. Without well-communicated objectives, stakeholders, including Government of Canada staff and industry representatives, cited difficulties in determining which activities to undertake and to what end.

While the Strategy outlines the expectation that Canadian companies operating abroad will “reflect Canadian values” and “embody CSR best practices,” it does not include an explanation of what it means to do so in practice. It is difficult to hold Canadian companies accountable for not reflecting Canadian values if these values are not defined or measureable. This lack of clarification made it impossible for the evaluation to determine whether Canadian operations abroad were aligned with the Strategy.

Finally, the target audience is not well-defined within the Strategy. The Strategy names Canadian extractive sector companies as the primary audience, yet it also aims to provide an overview of Canada’s approach to CSR to “a more general audience”. In addition, the Strategy promotes international guidance, such as the OECD Guidelines for MNEs, which is applicable to all sectors. As a result, industry and civil society stakeholders have questioned whether the Strategy is aimed only at the extractive sector, or if expectations are applicable to all Canadian companies operating abroad.

While the Strategy targets Canadian companies, it also includes guidance aimed at Government of Canada staff, who are the main delivery agents. With such a broad range of stakeholders identified within the Strategy, it is perceived as a mixed internal and external document that does not adequately define actions based on the unique challenges and perspectives of each stakeholder group.

Finding 12. There was no clear guidance on the overall implementation and delivery of the Strategy.

Accompanying items to a strategy

Text version

The diagram illustrates the various items that should accompany a strategy. The circle in the centre represents the strategy. The six circles surrounding the circle represent the accompanying items: Roles, Budget, Logic Model, Action Plans, Outreach, Organizational Chart.

Literature stipulates that the development of a strategy alone, regardless of its content, is not sufficient to achieve its intended objectives. A corresponding implementation plan is needed to allocate resources, clarify roles, responsibilities, and timeframes, as well as parcel the content into actionable items. The evaluation found that while Global Affairs Canada’s Responsible Business Practices Division developed an internal implementation plan, it was specific to the Division and did not guide the work of all delivery agents.

The 2013 evaluation of Canada's initial CSR Strategy found a lack of mechanisms in place to assign responsibility and assess progress. Correspondingly, the evaluation recommended that the program area elaborate a plan to clearly identify how the Strategy would be implemented. This recommendation was not fully implemented with the development of the 2014 Strategy.

The Strategy identifies a number of government departments involved in its implementation. However, the evaluation found no document outlining the roles and responsibilities for participating departments. Industry and civil society representatives were unclear as to what roles Global Affairs Canada and Natural Resources Canada play in the delivery of the Strategy, and expressed a desire for an organizational chart or document that depicts responsibilities. Participants from a multi-stakeholder focus group highlighted the importance of ensuring that all relevant actors are engaged, that expertise and contacts are leveraged, and initiatives coordinated.

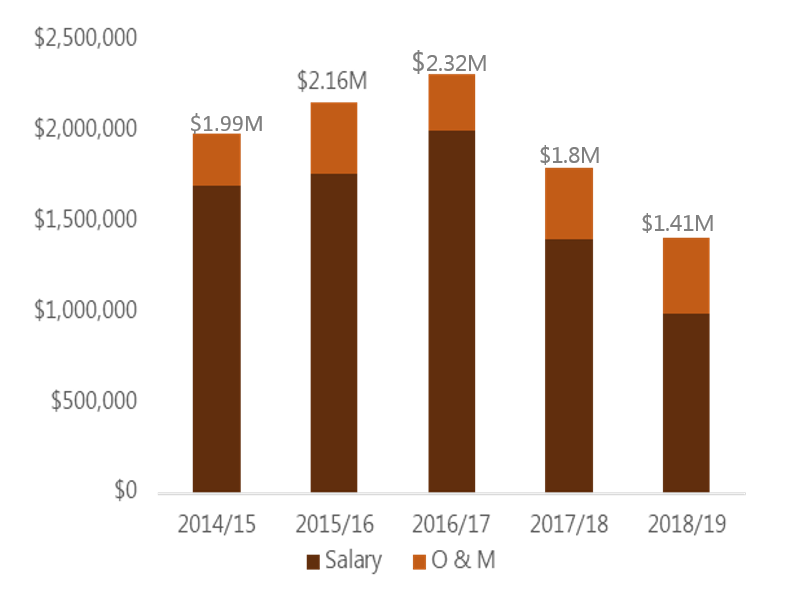

An overarching budget and operating plan specifying resources and funding needed to achieve the Strategy’s goals were not developed. The implementation of the Strategy at Global Affairs Canada and Natural Resources Canada was funded by existing departmental resources. According to staff, the absence of dedicated funding impacted the long-term planning of initiatives for CSR promotion.

While the Strategy was widely found to highlight important areas for action through the four pillars, it provided little guidance on what could feasibly be achieved in vastly different operating contexts. Delivery agents suggested that detailed action plans tailored by pillar or by stakeholder group could have provided guidance for implementation. In the absence of such guidance, the scope of activities undertaken by delivery agents were identified and developed individually rather than as a set of coordinated initiatives.

The Strategy also lacks an accompanying monitoring and evaluation plan to allow for the measurement of progress. While a logic model was developed to guide the work of the Responsible Business Practices Division at Global Affairs Canada, it was not inclusive of all delivery agents, namely Natural Resources Canada. This impacted the evaluation’s ability to effectively measure results of the activities undertaken, as outcomes, indicators, and targets were not articulated nor consistently reported.

Finally, a communication plan that details outreach to key stakeholders is important in delivering the Strategy’s message. While the Responsible Business Practices Division had a number of approved communication products available on internal and external websites, the evaluation did not find a proactive communication plan, accessible to and inclusive of all delivery agents.

Finding 13. A formal horizontal governance structure was not established to effectively manage the delivery of the Strategy.

Despite the Strategy being a horizontal initiative, the evaluation found no overarching governance structure in place between Global Affairs Canada and Natural Resources Canada, making it unclear how decisions on delivery were made. A formal governance structure provides a framework for decision-making and contributes to transparency and accountability. It can help to ensure that all delivery agents are involved in the development, implementation, and monitoring of activities.

Horizontal structure

The delivery of the Strategy was managed without a formal horizontal governance structure or decision-making committee. Nonetheless, staff reported that communication between Global Affairs Canada and Natural Resources Canada was ongoing with respect to CSR initiatives and issues. Staff stated that the informal structure works well for the delivery of the Strategy at this time, but that roles and responsibilities could be clearer to ensure effective and ongoing coordination as staff rotate out of positions.