Evaluation of the Mission Cultural Fund 2016/17 to 2019/20

Evaluation Report

Diplomacy, Trade and Corporate Evaluation Division (PRE)

Global Affairs Canada

November 2020

Table of Contents

- Executive summary

- Mission Cultural Fund Background

- Evaluation Scope and Methodology

- Findings

- Conclusions

- Recommendations

- Management Response and Action Plan

- Annex 1: Acronyms

- Annex 2: MCF Theory of Change

- Annex 3: List of Sources

Executive summary

The Mission Cultural Fund (MCF) is an operational fund administered by the Cultural Diplomacy Unit and supported by mission liaison officers in the Mission Support Division (NMS) at Global Affairs Canada (GAC). Intended to be a tool dedicated to restoring the foundations of cultural diplomacy at GAC, available to missions abroad, the MCF was created and funded as part of two Canadian Heritage-led initiatives: Showcasing Canada’s Cultural Industries to the World (FY 2016/17 to FY 2017/18) and the Creative Export Strategy (FY 2018/19 to FY 2022/23).

The evaluation of the Mission Cultural Fund was conducted at the request of the Cultural Diplomacy Unit in the Geographic Coordination and Mission Support Bureau (NMD). The objectives of the evaluation were to assess the relevance, effectiveness, delivery and efficiency of the MCF during the four years following its creation in 2016. The timing of the evaluation is aligned with the work on the design of the upcoming Global Affairs Canada-led Cultural Diplomacy Strategy.

The evaluation confirmed the ongoing need for the MCF as a tool for engaging the department in cultural diplomacy. NMS and missions built successful partnerships with Canadian and foreign local partners and leveraged additional funding for implementing a large number of cultural initiatives. During the evaluation period, cultural initiatives contributed to promoting abroad Canadian artists and cultural organizations, who were good ambassadors of Canadian values of diversity and inclusion.

Cultural initiatives contributed to achieving multiple results, including increased opportunities for Canadian artists and access to a wide range of decision-markers and influencers for Global Affairs Canada’s representatives and Canadian artists. The evaluation also found that the MCF contributes to additional outcomes, including support to bilateral relations via la Francophonie; increased visibility for Canada and Canadian missions abroad; and increased community engagement.

The evaluation identified several factors that have impeded MCF’s effective administration and delivery as well as the performance measurement of cultural initiatives: the absence of a formal governance structure; unclear roles and responsibilities; the lack of a strategic framework, including evidence-based priorities and a theory of change better adapted to MCF; insufficient dedicated positions at missions; and inconsistent funding levels.

Missions identified additional challenges in the delivery of cultural initiatives, among which the current funding mechanism is the most significant.

Due to data quality issues, the evaluation could not determine the extent to which cultural initiatives contribute to increased awareness of Canada’s foreign policy priorities.

Summary of recommendations

- Establish a formal governance structure for decision making and clearly articulated roles and responsibilities for internal and external stakeholders involved in the administration and delivery of the MCF at HQ and missions abroad. This may include formalizing interdepartmental and intradepartmental collaboration to ensure that objectives, policies and programs are coordinated and areas of concentration and possible duplication are identified.

- Elaborate a strategic framework for the MCF, aligned with the department’s current foreign policy and regional priorities. In support of this framework, develop operational guidelines and tools as well as a formal project assessment process to ensure transparent and equitable funding allocation. This may include considering international best practices in like-minded countries and introducing a specific stream aimed at supporting cultural initiatives in developing countries and ultimately increasing the diplomacy-international aide nexus; conducting extensive consultations with missions (including those that did not implement cultural initiatives) to identify capacity challenges and/or training needs.

In support of this framework, develop operational guidelines and tools as well as a formal project-assessment process to ensure transparent and equitable funding allocation. - Adapt the FPDS theory of change and performance indicators to support results reporting and to reflect the contributions of cultural initiatives to achieving MCF’s objectives, and create monitoring mechanisms for their implementation.

Mission Cultural Fund Background

General Overview

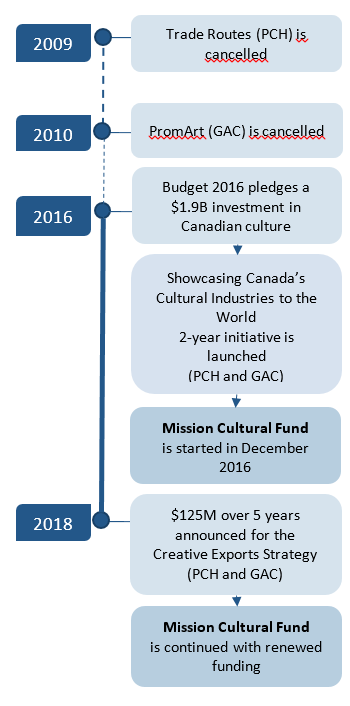

The 2016 Budget announced a historic investment of $1.9 billion over 5 years in Canadian culture, largely aimed at increasing the budgets of key Canadian arts funding agencies such as the Canada Council for the Arts, Telefilm Canada and the National Film Board. This investment allowed GAC to re-engage in cultural diplomacy through the MCF, which was launched in December 2016 as part of a Canadian Heritage-led initiative.

Showcasing Canada’s Cultural Industries to the World (FY 2016/17 to FY 2017/18)

The MCF was launched in December 2016 as part of a two-year initiative Showcasing Canada’s Cultural Industries to the World dedicated to the promotion of Canadian artists and creative industries abroad.

Led by the Department of Canadian Heritage (PCH) and supported by GAC through the Foreign Policy and Diplomatic Service (FPDS) and the Trade Commissioner Service (TCS), the initiative aimed at re-linking with the objectives of former Trade Routes at PCH and PromArt at GAC. Both programs, supporting creative exports and cultural diplomacy, were eliminated in 2009 and 2010 respectively, in the context of a government expenditure review exercise.

As part of the same initiative, a new creative industries envelope was created within the Integrative Trade Strategy Fund (ITSF), administered by BBI. The focus of this envelope was on export and market development activities for creative industries.

Creative Exports Strategy (FY 2018/19 to FY 2022/23)

Building on the prior initiative, a new PCH-GAC investment allowed the MCF to continue to re-engage the department in cultural diplomacy and promote Canadian artists and cultural organizations abroad. Thus, in June 2018, PCH, in collaboration with GAC, announced an investment of $125 million over 5 years to implement Canada’s first Creative Export Strategy, with the objective of promoting Canada’s creative industries by strengthening Canadian presence abroad. The strategy is built around 3 pillars:

- Boost export funding in several existing PCH programs.

- Increase the presence of Canadian creative industries abroad through additional resources in key Canadian missions.

- Develop a creative export funding program at PCH and build the relationships needed to make business deals.

Resources

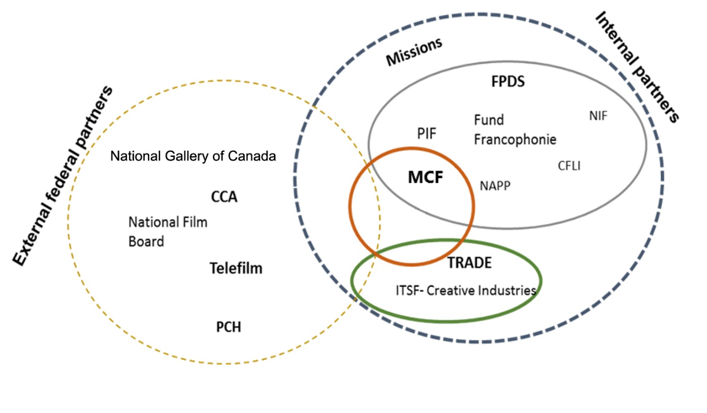

MCF is an operational fund administered at headquarters by 6 FTEs in the Cultural Diplomacy Unit of the Geographic Coordination and Mission Support Bureau (NMD). Together with the Canada Fund for Local Initiatives (CFLI) and the Post Initiative Fund (PIF), the MCF is embedded in the Advocacy Funding stream of the Mission Support Division (NMS).

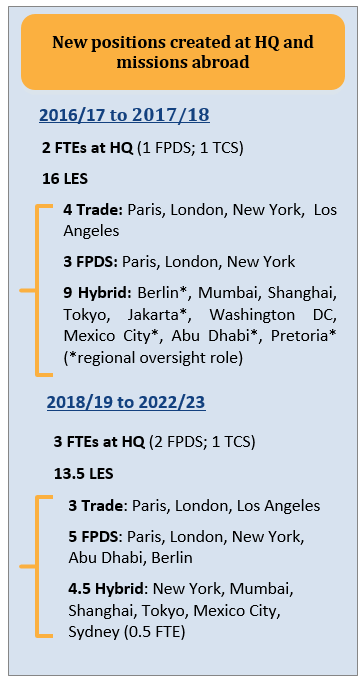

The MCF has a $1.75 million annual envelope available to missions and Canadian cultural centres abroad for implementing cultural initiatives. As part of the PCH-GAC initiatives, additional resources were also pledged for creating new positions at HQ and missions to rebuild capacity and to support the delivery of the mandates of the two departments, related to the promotion of Canadian artists, creative industries exports and cultural diplomacy.

The number, level and stream of new LES positions dedicated to the delivery of the MCF has varied over the evaluation period. While 9 hybrid positions were created to deliver on both FPDS and trade initiatives during the first two years of the MCF, their number was reduced to 4.5 positions in 2018.

The same year, the number of FPDS positions at missions increased from 3 to 5. Furthermore, trade LES positions are exclusively dedicated to supporting the new Creative Export Envelope of ITSF.

Table 1 illustrates the annual MCF planned expenditures during the evaluation period, supported through the two PCH-GAC engagements. It also provides an overview of the overall breakdown of planned resources between PCH and GAC during the same period.

| Showcasing Canada’s Cultural Industries to the World | Creative Exports Strategy | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016/17 | 2017/18 | 2018/19 to 2022/23 | |

| * In 2017/18, the MCF’s baseline budget was substantially increased to $5 million, in the context of the Canada 150 celebrations. | |||

| New FTEs | 9 | 19 | 16.5 |

| New Funding | $4M | $11.4M | $30M |

| Funds Expenditure per year | |||

| MCF | $1.75M | $5M* | $1.75M |

| ITSF | $250 000 | $250 000 | $250 000 |

Evaluation Scope and Methodology

Evaluation Scope and Objectives

Evaluation Scope

The evaluation covers the MCF’s activities, delivered by Global Affairs Canada at HQ and missions abroad, between FY 2016/17 and FY 2019/20. As funding for the new MCF was approved at the end of 2016, only the period from December 2016 to March 2017 was covered for FY 2016/17.

The evaluation was conducted between December 2019 and June 2020 by the Diplomacy, Trade and Corporate Evaluation (PRE).

Evaluation Objectives

The evaluation of the Mission Cultural Fund is a discretionary evaluation conducted at the request of the Cultural Diplomacy Unit at NMD.

The evaluation complies with the requirements of the 2016 Policy on Results and provides senior management with a neutral and evidence-based assessment of the relevance, efficiency and progress toward the achievement of the MCF’s expected results. The timing of the evaluation is aligned with the design of the upcoming GAC-led Cultural Diplomacy Strategy.

Evaluation Questions

| Evaluation Issue | Questions |

|---|---|

| Relevance and Coherence | Q1. To what extent is the MCF aligned with the departmental mandate and Canada’s foreign policy priorities? Q2. To what extent is the MCF aligned and leveraging synergies with other funds at GAC; other departments, portfolio agencies and Canadian organizations in the arts and culture field? |

| Effectiveness | Q3. To what extent is the MCF achieving expected outcomes:

|

| Efficiency and Delivery | Q4. To what extent are NMS and missions effective in delivering MCF (for example, funding mechanism; governance structure; project assessment; reporting and performance measurement)? Q5. What are the current international best practices in terms of cultural diplomacy approaches? |

Methodology

Document Review

The evaluation team reviewed a large number of documents including departmental reports, Strategia and MCF internal documents and reports. The document review included a mapping of 3 internal funds and 10 funds delivered by other federal organizations involved in the implementation of the Creative Exports Strategy.

Literature Review

A comparative literature review examined cultural diplomacy approaches in 6 like-minded countries (United Kingdom, France, Netherlands, South Korea, Japan and Australia) and provided relevant information on their programming, strategic objectives, governance models, funding mechanisms and performance measurement.

Strategia Data Mining and Project Review (n=122)

The evaluation team performed an analysis of Strategia data for MCF initiatives.

The quantitative data analysis was complemented in February 2020 by a qualitative review of 10% of MCF-completed initiatives available for the period between 2016/17 and 2018/19 (122 initiatives).

The objective of the project review was to determine the extent to which initiatives contributed to achieving the MCF’s objectives and were aligned with foreign policy priorities, based on descriptive presentations of reported results. Data mining and project review also allowed thee identification of Strategia data quality and gaps.

Stakeholder Interviews (n=38)

Semi-structured interviews were conducted, in person and by telephone, with a diversity of key stakeholders:

- Global Affairs headquarters staff, including program managers and analysts (n=10)

- LES and CBS involved in delivering MCF-funded initiatives at missions abroad (n=23)

- External stakeholders in relevant departments and portfolio agencies (n=5).

Case Studies (n=14)

The evaluation team travelled to 3 missions in Europe (Berlin, Rome and Oslo). Missions were selected in consultation with NMS. Selection criteria included the amount of funding received and the number of projects delivered during the evaluation period.

As part of the site visits, the evaluators conducted interviews with FPDS staff at missions, representatives of like-minded countries and local partners and attended two cultural initiatives. Interviews with local partners were triangulated with information from other sources (Strategia data, organization websites and reports) to carry out 14 case studies that shed light on the partners’ experience with Canadian missions and contributed to a better understanding of the MCF’s outcomes.

Evaluation Limitations and Mitigation Measures

1. Lack of reliable and inconsistent Strategia data

During the reference period, incremental changes to performance indicators and reporting categories for cultural initiatives in Strategia hindered the evaluation’s capacity to draw out longitudinal trends.

Inconsistent and/or inaccurate reporting of the results and financial resources of cultural initiatives, uncertainty on data sources used to report on performance indicators, and no systemic data collection mechanism used to measure the impact of cultural initiatives (surveys assessing increased awareness on foreign priorities) limited the reliability of the data reported in Strategia and their use for evaluation purposes.

Mitigation Strategy

The evaluation conducted an in-depth review of a sample of cultural initiatives and linked Strategia MCF funding data to the actual MCF budget.

2. Lack of data for and from direct beneficiaries of the MCF

Currently, there are no performance indicators for the number and type of Canadian artists supported through the MCF. Information on local and Canadian partners, including type of partnerships and complementary funding, is inconsistently reported by missions.

Mitigation Strategy

The evaluation partially mitigated this limitation. Case studies, project review and interviews allowed for the collection of information on partners’ experience with Canadian missions and some of the Canadian artists supported through MCF initiatives.

3. Multiple funding sources for cultural initiatives

The attribution of results is limited as the MCF is intended to be a complementary fund. In many cases, the MCF represents a small contribution in the complex and multi-sourced funding mechanism of cultural events.

Limited data on funding sources (federal, provincial, local partners) prevented the evaluation from accurately assessing the MCF’s contribution to achieving expected outcomes.

This limitation could not be mitigated. Changes to reporting for cultural initiatives are required.

4. Limited engagement with missions that did not implement cultural initiatives

The majority of interviews were conducted with missions where cultural initiatives have been implemented. Non-participation of missions that did not deliver any MCF initiatives (additional interviews could not be conducted due to the COVID-19 context) limited the understanding of possible challenges and obstacles they have encountered.

Further consultations with missions by NMD are required.

Findings

Continued Need for the MCF

The evaluation confirmed the ongoing need for the MCF as a tool for implementing cultural diplomacy at Global Affairs Canada.

Cultural diplomacy “encompasses a range of activities orchestrated by diplomats employing cultural products to advance state interest, for instance, involving art, literature and music.”

- Cultural Diplomacy at the Front Stage of Canada’s Foreign Policy - June 2019 (Standing Senate Committee on Foreign Affairs and International Trade, Canada)

Public diplomacy has a long history as a means of promoting a country’s soft power. Placed as a main sub-area of public diplomacy, cultural diplomacy functions by attraction and is considered to be a soft-power tool. If culture and ideology are attractive, others will be more willing to follow.

Cultural diplomacy springs from two premises:

- good relations can take root in the fertile ground of understanding and respect, with a focus on cooperation, and

- cultural diplomacy rests on the assumption that art, language and education are among the most significant entry points into a culture and can facilitate obtaining advantage in a foreign country. (Goff, Patricia, 2013)

The evaluation found that there is an ongoing need for the MCF as a tool for supporting cultural diplomacy at GAC. Even if not directly referred to, the MCF’s relevance is reinforced through mandate letters and official reports, pledging the department’s commitment to increase Canada’s educational and cultural interaction with the world.

The 2015 Minister of Foreign Affairs mandate letter announced the department’s support to the Minister of Canadian Heritage to restore the PromArt and Trade Routes International cultural promotion programs. This commitment was concretized through the creation of the MCF in 2016 and its renewal in 2018.

In June 2019, the importance of cultural diplomacy was reiterated by the Senate report - Cultural Diplomacy at the Front Stage of Canada’s Foreign Policy. The main conclusion of this report was that cultural diplomacy should be a pillar of Canada’s foreign policy. Several recommendations stemmed from the report, including the development and implementation of a GAC-led whole-of-government cultural diplomacy strategy.

The most recent Minister of Foreign Affairs mandate letter reiterated the need to continue the revitalization of Canada’s public diplomacy, stakeholder engagement and cooperation with partners in Canada by introducing a new Cultural Diplomacy Strategy with at least one international mission every year to promote Canadian culture and creators around the world.

There is unanimous consensus among interviewed stakeholders on the ongoing need for the MCF as a tool for the department to re-engage in cultural diplomacy. In fact, during the interviews, stakeholders used MCF and cultural diplomacy interchangeably.

The need for the MCF is even more relevant in the context of a strong international competition among like-minded countries for positioning themselves in terms of influencing, building partnerships and increasing trust and attractiveness among foreign audiences.

A comparative literature review of six cultural diplomacy approaches demonstrated the continuous commitment of like-minded countries to providing solid funding in support of cultural diplomacy programming and related institutions. Furthermore, the review showed that, in like-minded countries, cultural diplomacy efforts are orchestrated by foreign affairs ministries and enhanced through close collaborations and partnerships with other government departments and agencies.

Collaborations and Partnerships

NMS and missions have collaborated with several funds at Global Affairs Canada, and with federal and cultural organizations, to deliver joint cultural initiatives.

The MCF’s design as a complementary fund makes partnerships and collaborations an integral part of its successful delivery. Collaboration with departmental funds and external federal and national cultural organizations provided NMS and missions with input on the cultural sector as well as complementary investment and support.

Intradepartmental collaboration

The MCF is often jointly used with other FPDS funds, including the Post Initiative Fund (PIF), the Northern America Partnership Program (NAPP) for initiatives implemented in North America, or funding dedicated to supporting la Francophonie, among others.

Cultural initiatives that cross public affairs and trade domains offer possibilities for greater departmental cohesion and strengthened ties between diplomacy and trade sectors at missions. Hybrid LES often implement cultural initiatives at the intersection of cultural diplomacy and trade. Interviews and project review also identified examples of effective collaboration between trade and FPDS sections in delivering joint activities.

The evaluation also found a few examples of collaboration where the MCF was used to support international assistance priorities. For example, in Colombia, culture was used to increase the visibility of Canada’s role in peacebuilding. However, interviewees currently or previously working in developing countries expressed the need for stronger linkages between cultural diplomacy and development priorities such as women and girls’ empowerment, anti-corruption and peacebuilding.

Interdepartmental collaboration

The evaluation found that collaboration between Global Affairs Canada (HQ and missions), PCH and portfolio agencies, and other major cultural organizations (for instance, National Gallery, National Film Board) contributed to informing missions of opportunities to promote Canadian artists, and to increasing the funding and programming of cultural initiatives.

As stated in the 2018/19 MCF Annual Report, NMS invested $6.1 million in partnerships with CCA, PCH, Telefilm and other organizations to support joint projects at the Venice Biennale in Italy, CanadaHub at Festivals Edinburgh in the United Kingdom, the Festival Africa. Internacional Cervantino in Mexico, and the Abidjan Performing Arts Market (MASA) in West Africa.

Global Affairs Canada, through the MCF, Canada Council for Arts and PCH are partnering to implement the largest common endeavour since the creation of the Creative Exports Strategy: the participation of Canada as a guest of honour at the Frankfurt Book Fair in October 2021 (postponed from 2020 due to COVID-19).

Figure 1. Main MCF Federal Partners

Number and Type of Cultural Initiatives

The MCF allowed the delivery of a significant number of cultural initiatives, among which the large majority were cultural events aimed at supporting Canada’s values and brand.

Of completed initiatives in 2018/19 and 2019/20

9 out of 10 were cultural events

74% were under the theme Canadian values and brand

Main artistic genres supported

Film – 19%

Music – 17%

Visual arts – 15% of initiatives

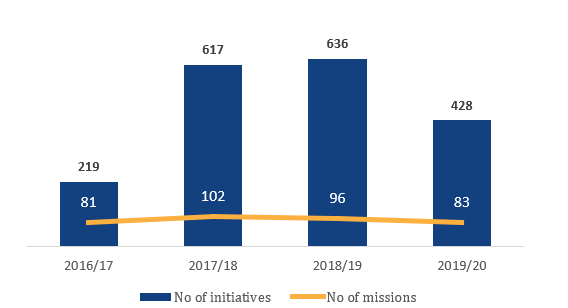

In 2017/18 and 2018/19 the number of initiatives almost tripled compared to 2016/17, followed by a steep decrease in 2019/20 due to a larger number of cancelled initiatives in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and less MCF funding available to missions. During the same period the number of missions delivering cultural initiatives remained relatively stable (Figure 2).

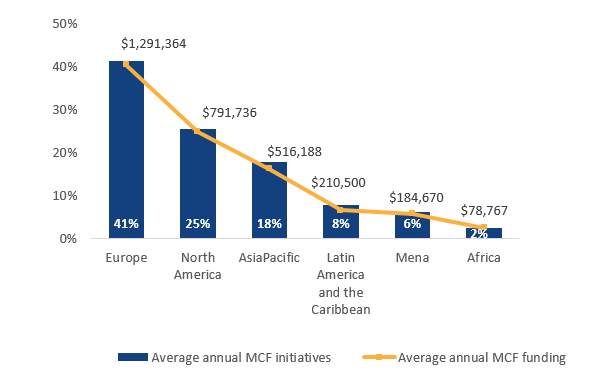

As shown in Figure 3, between 2016/17 and 2019/20, missions in Europe delivered the highest proportion of cultural initiatives (41%), followed by missions in North America (25%) and Asia Pacific (18%). The number of completed initiatives in each region is generally consistent with the proportion of actual MCF funding allocated.

Based on data reported through Strategia, MCF initiatives achieved their expected results to a large extent. In 2018/19 and 2019/20, 82% of initiatives met all or almost all planned performance indicators, 10% met at least half of them, and only 5% achieved less than half of their targets.*

Figure 2: Number of cultural initiatives and missions delivering MCF, 2016/17 to 2019/20

Source: Strategia

* Performance indicators on the initiatives’ desired change and types of audience, as well as data on types of cultural initiatives, have begun to be collected in Strategia starting with 2018/19.

Text version

| Fiscal years | Number of initiatives | Number of missions |

|---|---|---|

| 2016/17 | 219 | 81 |

| 2017/18 | 617 | 102 |

| 2018/19 | 636 | 96 |

| 2019/20 | 428 | 83 |

Figure 3: Average proportion of cultural initiatives and MCF actual funding by region, 2016/17 to 2019/20

Source: Strategia, MCF actual funding

Text version

| Regions | Average annual MCF Initiative | Average annual MCF funding |

|---|---|---|

| Europe | 41% | $1,291,364 |

| North America | 25% | $791,736 |

| Asia Pacific | 18% | $516,188 |

| Latin America and the Caribbean | 8% | $210,500 |

| Middle East and North Africa | 6% | $184,670 |

| Africa | 2% | $78,767 |

Effectiveness: Canadian Artists and Local Partners

Cultural initiatives have successfully supported Canadian artists and artistic organizations through effective collaboration with a wide range of local partners.

One of the MCF’s objectives is to support the participation of Canadian artists and organizations in cultural events and activities abroad. In order to achieve this objective, missions are expected to build local partnerships and leverage the existing cultural programming.

The evaluation found that cultural initiatives contribute to supporting Canadian artists and cultural organizations, and increase the visibility of Canadian art and culture through media coverage and by introducing Canadian artists and creators in countries where they would not have been featured otherwise.

For example, 40% of the 2017/18 and 2018/19 reviewed projects contributed to promoting Canadian culture and artists abroad and 9 out of the total of 14 case studies led to increased visibility for Canadian artists due to their participation in events that were part of prestigious and recognized international festivals.

Missions supported a great number of artists and organizations, many of them having been already endorsed by important Canadian funders (for example, Canada Council for Arts, Quebec Delegation, Telefilm) as a guarantee of their artistic excellence.

Local partners claimed that Canadian artists are good ambassadors in areas such as diversity and inclusion, by providing space to reflect on the topic at hand. It is important to note that thematic topics are approached by artists from a critical and independent perspective, and not from a propaganda perspective, nor as representatives of the Canadian government. This approach fosters dialogue on sensitive topics and conveys the image of a democratic country.

Missions establish successful collaborations with local partners

Missions have been successful in networking and collaborating with a wide range of local organizations in the arts and cultural sector as well as public and private organizations, including local governments and agencies. Most Strategia MCF initiatives include reference to at least one potential local partner: festivals and cultural organizations or like-minded cultural organizations (for example, British Council, Alliance Française, Institut Français, foreign embassies).

Case studies showed that in Rome, Berlin and Oslo, cultural initiatives were the result of collaboration with prominent and renowned local organizations, having solid and impactful audiences in their field of expertise (Berlin Film Festival, Venice Biennale, major international dance, film and music festivals). This collaboration stems from both pre-MCF, long-lasting trust-based relationships, and new relationships, leveraged by the MCF. Furthermore, long-lasting partnerships contributed to an increased Canadian artistic presence in recent years, and in some cases, led to Canada being featured as the event’s guest of honour while providing missions’ representatives with the opportunity to participate in panel discussions, introduce the artists’ participation and be present in social and traditional media.

While local partners estimated that the collaboration with Canadian embassies is a best practice in terms of flexibility and reliability, it was also noted that, in some cases, the planning cycle of large and prestigious events is long-term. Thus, there is a need to know in early stages if funding is available as a confirmation of the working relationship with Canadian missions.

Effectiveness: Increased Opportunities for Canadian Artists

The MCF is a successful tool for building international professional networks and leveraging increased professional opportunities abroad for Canadian artists.

Examples of initiatives that have effectively created increased opportunities for Canadian artists

- The Los Angeles mission used the MCF to level-up the careers of Canadian filmmakers by funding their participation in New Filmmakers LA, which programmed 14 Canadian short films in one week and increased exposure to high-powered industry mentors.

- The Tel Aviv mission organized a market access initiative by inviting 10 regional presenters to the first Canadian dance festival in Israel in order to leverage more touring opportunities; as a result, 3 Canadian companies ended up with additional contracts.

- The Dallas mission organized an outreach visit to Manitoba Indigenous Arts Centres for American museum curators. This resulted in Canadian Indigenous exhibits being presented in the south-western United States.

The evaluation found that by promoting Canadian artists’ participation in cultural events abroad and supporting various networking activities, the MCF contributed to increasing interactions and opportunities for further collaborations and performance venues. While it is not possible to determine the extent of this contribution, this is a significant MCF outcome highlighted in several lines of evidence.

About 15% of the 2017/18 and 2018/19 reviewed initiatives contributed to creating increased opportunities for Canadian artists abroad (for example, additional touring venues and contracts for Canadian artists; Canadian books translated and published in other countries).

One specific approach used by missions to leverage artistic encounters and opportunities for Canadian artists is to support the participation of foreign decision makers and buyers from the artistic and cultural sectors in international networking events taking place in Canada (such as CINARS and Mundial in Montréal, Canadian Music Week in Toronto), for reciprocity of exchanges. This approach is particularly appreciated by local partners and indicated as a best practice when compared with other like-minded countries. It contributes to increasing knowledge of the Canadian creative industries and facilitates building networks between Canadian artists and international cultural organizations and buyers.

Case studies included 6 organizations supported by missions to travel to Canada. For example, in 2018, with the support of the MCF, 3 Norwegian buyers travelled to CINARS and Mundial. This resulted in 9 bookings for Canadian artists over the following 18 months. An additional example features a delegation of the international indigenous festival Riddu Riddu in Norway that travelled to Nunavut in 2018. This led to about 20 Indigenous artists being invited to the 2019 Riddu Riddu festival the following year, when Canada was featured as the guest of honour.

Effectiveness: Increased Awareness of Canada’s Foreign Policy Priorities

One of the MCF’s main objectives is to increase the awareness of Canadian foreign policy priorities among foreign key targeted audiences. The evaluation could not determine the extent to which cultural initiatives contribute to achieving this objective.

Based on Strategia data, 86% of the completed initiatives in 2018/19 and 79% of those delivered in 2019/20 were intended to increase or maintain awareness of non-targeted and targeted audiences of various aspects (for instance, Canadian values and brand; Canada’s policies and priorities; Canada’s excellence in culture, innovation and progressive values).

Several factors limited the evaluation’s capacity to estimate the extent to which the MCF contributed to increased awareness of its thematic priorities among foreign audiences, such as: inconsistent and incomplete data reporting; lack of direct data collection from audiences, and the complementary nature of the MCF that is expected to build on existing cultural events and be used in association with other funding sources.

The evaluation also found that cultural events cannot be equalled to advocacy strategies that convey purposeful messaging on foreign policy priorities intended to a pre-identified targeted audience. In many cases, existing cultural events have an already well-established audience and themes upon which missions do not exert a direct influence. It is the choice of Canadian artists supported by missions (Indigenous, women, LGBTQ) that is most often indicated to have led to possible increased awareness of Canadian values. For example, one mission defined their objective as promoting the equal participation of male and female artists, and at least 20% of Indigenous artists.

In other cases, it is the message conveyed by the work of Canadian artists or the characteristics of their artwork that became a vehicle for awareness of Canadian values. For example, an initiative supported by the Tunis mission, the play Comment je suis devenu musulman, engaged the audience on how Canada embraces diversity and religious freedom, which was considered to be “inspirational” for a new democracy where Muslims are looking to take moderate paths.

The values or themes promoted by cultural events are another means leveraged by missions to promote Canadian values. Some festivals promote themes and values that are similar to Canadian values and priorities such as identity, human rights, gender equality, exile and migration, diversity and inclusion, Arctic experience, or Indigenous rights and arts. Canadian artists are invited because they are considered to be relevant to the themes promoted by these cultural events.

For example, the Paris mission supported the presence of Canada as a guest country at the world’s only performing arts festival for the deaf and hard-of-hearing—Clin d’Oeil in Reims, France—as an opportunity to showcase Canada’s progressive values with respect to disabled people.

Multipurpose participation in cultural events

The evaluation found that one effective way of contributing to an increased awareness of Canadian values among foreign audiences is the multipurpose participation of artists in cultural events. They not only share their artwork, but also run workshops or participate constructively in panel discussions. This multipurpose participation allows for an open dialogue with audiences, contributing to increased mutual understanding.

Case studies included several examples of similar initiatives. The evaluation team attended a panel held by Wapikoni Mobile as part of the Berlin Film Festival demonstrating how their artwork is used as a tool to build stronger communities. The panel facilitated a dialogue on Canadian values and best practices, while also tackling stereotypes and challenges encountered by Indigenous people.

In another case study, the screening of the Canadian film The Grizzlies at the Tromsø International Film Festival was accompanied by an exchange with two of the actors, supported by the MCF, that helped to add context for the audience on a sensitive topic for Indigenous youth.

Effectiveness: Increased Access to Key Foreign Audiences

The MCF plays a key role in increasing access to a broad range of targeted and non-targeted audiences. In some cases, increased access led to increased willingness, mostly reflected in additional opportunities for Canadian artists.

Examples of initiatives that effectively created increased opportunities for Canadian artists

In 2019, the Oslo mission participated in the Oslo Pride Week, and hosted more than 500 guests at the official residence, including the foreign minister, the mayor of Oslo and the president of the Norwegian parliament.

In Rome, a music festival supported by the mission through the MCF provided missions with access to high officials representing the City of Milan and the regional government, and allowed Canadian artists to develop relationships with key decision makers from the Italian Federation of the Music Industry.

The Seattle mission used the MCF to support the participation of a Canadian artist during the Arctic Encounter Symposium—the largest annual Arctic policy conference in the United States. This facilitated access to U.S. senators and allowed for dialogue on Canada’s G7 priorities in the United States.

Cultural initiatives provide access to targeted and non-targeted audiences

The evaluation found evidence of the extent to which cultural initiatives play a key role in providing Canadian artists and GAC’s representatives with access to a broad range of targeted (decision makers and influencers from different areas) and non-targeted audiences. Access to decision makers and influencers is the first step toward creating new partnerships and expanding networks. Increased access also has the potential to leverage existing and future political, economic or cultural opportunities and priorities, without being necessarily aimed at achieving advocacy goals.

At least one third of the 2017/18 and 2018/19 reviewed initiatives provided access to key stakeholders from the political, cultural, artistic and civil society areas, including high-ranking officials and representatives of prominent cultural institutions. Interviews and case studies also demonstrated that cultural initiatives are successful in providing GAC representatives with increased access to decision makers and influencers.

Increased foreign key audiences’ willingness resulting from cultural initiatives

While in 2018/19, only 9% of initiatives aimed at increased willingness as a desired change, in 2019/20, their proportion increased to 15% of completed initiatives. A category of cultural initiatives aimed at increased willingness of key foreign audiences consisted in supporting the participation of foreign buyers in networking at international events taking place in Canada. Data-quality issues hindered the evaluation from determining the overall results of these initiatives aimed at increasing opportunities for Canadian artists. Lack of reliable data also prevented the evaluation from assessing the extent to which cultural initiatives led to increased willingness to support Canada’s foreign policy priorities.

The project review also revealed that some initiatives do not seem to be supporting the indicated desired change, or are not included in eligible spending criteria (for instance, a contract for assistance to deliver MCF initiatives was included as intended to increase willingness). Interviewees expressed mixed opinions on the capacity of cultural initiatives to increase willingness among decision makers on foreign policy priorities. Thus, it is not realistic to expect a decision maker to be willing to support Canada’s priorities based on attending one event only.

Effectiveness: Additional Outcomes

Cultural initiatives contribute to achieving additional outcomes that are not currently accounted for as part of the MCF’s objectives.

Cultural initiatives funded through the MCF have contributed to outcomes that are currently not measured in Strategia through specific indicators. These outcomes demonstrate the multiple possible positive impacts of the MCF as a tool for cultural diplomacy and further reinforce the fact that its objectives go beyond promoting foreign policy priorities.

Increased visibility for Canada and Canadian missions

One significant outcome of the cultural initiatives is the increased visibility and awareness about Canada and its values in different regions.

On one hand, the MCF contributed to making more people aware of Canada and its values and culture in distant regions and countries. On the other hand, the MCF also contributed to an increased Canadian presence in Europe and North America, in the context of Canada competing for visibility with other middle-power countries, which have much higher budgets dedicated to promoting their countries and culture. As highlighted by interviewees, in European countries like France and Germany, “You don’t exist if you don’t do cultural diplomacy!”

More specifically, the MCF contributed to increased visibility for Canadian missions abroad, facilitating the participation of GAC representatives in a multitude of cultural events that provided them with access to a diversity of key foreign audiences from various areas. For example, the MCF allowed the Berlin mission to be the only embassy featured on the official map of the Berlin International Film Festival.

Support to bilateral relations

The project review also revealed several examples of the effective use of the MCF to maintain and strengthen bilateral relationships (cultural and political). These could further contribute to increased support of Canada’s foreign interests, when relevant.

A MCF multipurpose initiative supported celebrations of the Canada-Vietnam 45th anniversary of bilateral relations, with activities addressing both large public and targeted audiences.

Support the departmental priority of promoting la Francophonie

Although not part of the MCF thematic priorities, several cultural initiatives contributed to supporting la Francophonie (alone or in combination with the MCF for la Francophonie), outlined as one of the core Canadian interests in the 2019 Minister of Foreign Affairs mandate letter.

Missions used their involvement in celebrating Journées de la francophonie as an opportunity to highlight the cultural and linguistic diversity in Canada, promote francophone artists and leverage other Canadian values such as human rights, environment and Indigenous issues.

The Buenos Aires mission uses the MCF to implement cultural initiatives in order to celebrate la Francophonie in Argentina and Paraguay every year, while promoting Canadian artists and values and increasing Canada’s visibility in the region.

Cultural initiatives contribute to increased community engagement

Anecdotal evidence shows that cultural initiatives may be good tools for increased community engagement.

In Turkey, the MCF was used to support filmmaking workshops for girls, including Syrian, Iraqi Yezidi children living in camps in Turkey’s predominantly Kurdish south-eastern province of Batman, within the framework of the first-ever International Children’s Film Festival. Following the activity, there was a noted increase in interest by the municipality and the University of Batman in educating girls in a positive artistic atmosphere.

Governance Structure

The MCF does not have a formal governance structure, and roles and responsibilities are not clearly defined.

Since the inception of the MCF in 2016, NMS has not established a formal governance structure. This gap is combined with unclear roles, responsibilities and accountabilities of HQ and mission staff involved in the administration and delivery of the MCF. In the absence of a formal governance structure, the evaluation was not able to determine how decisions related to various aspects of the MCF’s delivery are made.

MCF has an informal governance structure

The only formal consultation mechanism identified was the PCH-GAC senior management committee, which meets twice a year. The objective of the committee is to keep partners informed of each other’s activities.

The evaluation did not identify any other formal committees or consultation mechanisms with internal and external stakeholders initiated by NMS. Informal consultations and communications are preferred by NMS in order to avoid bureaucratic burdens and facilitate the MCF’s nimbleness.

Related to this, external stakeholders indicated that management should be more strategic, and that an evidence-based monitoring approach is needed to allow the realigning of cultural initiatives based on their results.

Unclear roles and responsibilities

Based on interviews, roles and responsibilities of HQ staff related to the administration of the MCF were described as: addressing requests for guidance and providing training on cultural diplomacy and the MCF; reviewing projects; negotiating and approving budgets; developing interdepartmental and intradepartmental partnerships.

Nevertheless, there are no internal documents that outline the roles and responsibilities of the various stakeholders and units involved in the administration, delivery and monitoring of cultural initiatives at HQ. In the context of an already limited capacity, a lack of clear roles and responsibilities may lead to decreased accountability.

The LES and CBS at missions abroad have “matchmaker, facilitator and catalyst” roles related to implementing cultural initiatives. They are expected to:

- map the local and Canadian art scene

- identify additional sources of funding through building cultural networks and partnerships with local partners and Canadian partners

- identify programming and present opportunities that can then be leveraged to promote foreign policy priorities.

There is, however, no clear description of roles and responsibilities related to the concrete business processes of planning and implementing cultural initiatives, including reporting on achieved results in Strategia.

Consequently, missions have uneven levels of understanding of their roles and responsibilities related to implementing MCF initiatives. While a few LES have extensive experience and in-depth understanding of both the local and Canadian cultural scene and partners, other interviewees expressed the need for clearer guidance on what can be done in terms of eligible initiatives.

Strategic Priorities

NMS has not developed an evidence-based strategic framework for the MCF that outlines funding priorities.

While several internal documents are dedicated to the Global Affairs Canada cultural diplomacy approach, NMS has not developed an evidence-based strategic framework that specifically outlines the MCF’s funding priorities, including a clear assessment of departmental needs and foreign policy priorities. This gap impacts the effective delivery of cultural initiatives, including the alignment of foreign policy priorities.

The MCF’s thematic priorities are partially aligned with the department’s foreign policy priorities

In 2017, NMS identified a set of thematic priorities, derived from the overarching themes of Canada 150—diversity and inclusion; human rights; Indigenous reconciliation; and environment. Later that year, “innovation and prosperity” were added to priorities. MCF internal documents do not include definitions of the priority themes, nor strategic guidance on how missions are expected to translate them into initiatives supporting these priorities.

An analysis of recent departmental planning documents, including mandate letters and the 2018/19 Departmental Plan shows that, while some of the MCF themes (diversity and inclusion, human rights, gender equality) cover broad core departmental values and interests, other themes (innovation and Indigenous reconciliation) are not directly aligned with the department’s mandate nor reflected in overarching foreign policy priorities. For the priority themes of environment and prosperity, there is an alignment with some of the department’s priorities. However, without operational guidance, these themes seem to be aligned in an ambiguous way.

A review of MCF-funded projects showed that the lack of strategic guidance has led, at times, to loose interpretations of priority themes by missions, translated into unclear alignment of initiatives with foreign policy priorities. This directly affects the achievement of the MCF’s objective to increase awareness of Canadian foreign policy priorities: about 25% of reviewed projects were not aligned to any of the announced themes.

In addition, the project review revealed a lack of understanding of what the MCF priority themes stand for. Missions use them under different labels (values, foreign priorities, thematic priorities) to reflect the possible alignment of initiatives to departmental foreign policy priorities. The same confusion reigns over the understanding of what Canada’s brand should be. It is defined inconsistently, through the use of a combination of key words such as: creative, innovative, excellent, progressive, diverse, inclusive.

Opportunities for a better alignment with regional priorities

A few interviewees suggested that NMS should develop a strategic approach for identifying geographic priorities for targeted cultural diplomacy activities. This would maximize the use of the MCF in the context of limited resources and capacity.

As an example, internal funds such as CFLI and ITSF adopt evidence-based strategic priorities, including targeted regions, for allocating funds. In the same vein, PCH has developed an International Market Priority Framework in order to effectively prioritize projects and inform the delivery of the Creative Exports Strategy. This evidence-based analysis helps PCH in determining priority markets.

The comparative literature review of cultural diplomacy approaches in like-minded countries showed that they all have targeted specific regions and countries and/or country-focused programs in order to align their cultural initiatives to foreign policy priorities aimed at strengthening and deepening bilateral relations. These tailor-made cultural diplomacy approaches are determined based on either economic, foreign affairs, international development and/or cooperation priorities.

Objectives and Performance Measurement

Diplomacy and Advocacy Theory of Change Components

Advocacy initiatives are expected to achieve one of the following three types of desired changes:

Awareness: Make the audience aware that a problem or potential policy solution exists.

Willingness: Transitional stage, where awareness is transformed into a sense of urgency and relevance that is the precursor to an audience taking action once the opportunity arises.

Action: Policy efforts support or facilitate audience action on an issue.

Audiences are the individuals and groups that advocacy strategies target and attempt to influence or persuade. They may be:

Targeted – Can be named by name or position (influencers, decision makers)

Non-targeted – Cannot be named by name or position (general public)

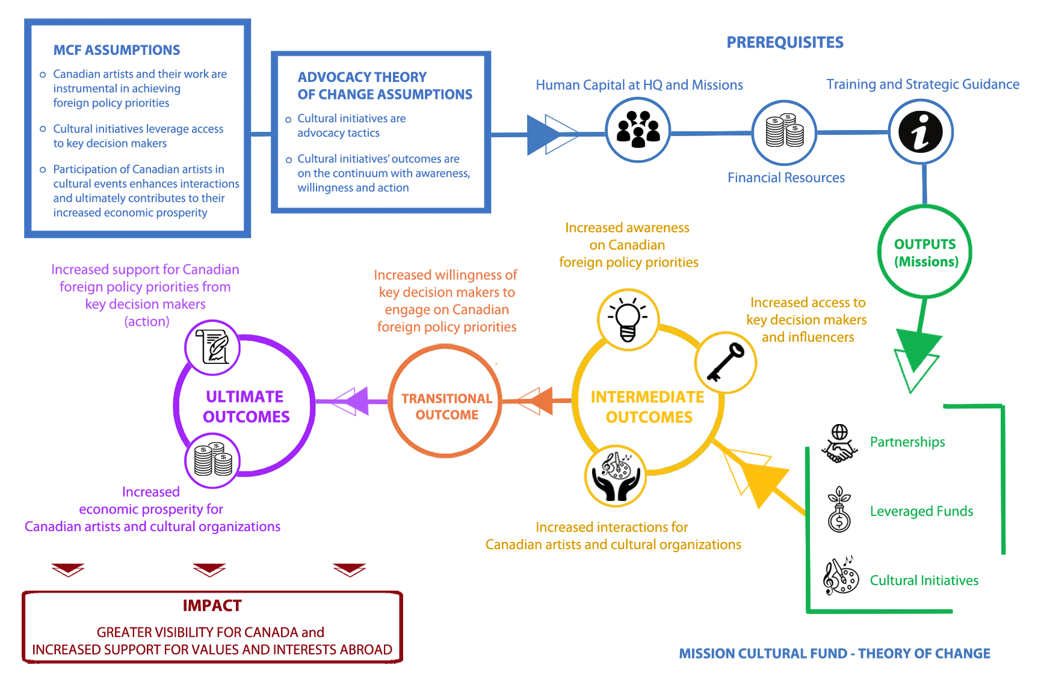

The lack of a specific MCF theory of change and performance indicators limits the capacity to accurately and adequately report on results.

The evaluation found that the lack of a specific MCF theory of change and performance indicators, as well as misalignment between MCF’s current objectives and advocacy outcomes, limits missions’ capacity to accurately and adequately report on all possible results of cultural initiatives.

The MCF objectives, as stated in internal guidelines, are to:

- increase awareness of Canadian foreign policy priorities by key target audiences (advocacy)

- increase and maintain access to key target audiences (access)

- increase opportunities for Canadian artists and arts organizations to perform and work overseas (economic prosperity)

The fund is embedded in the Diplomacy and Advocacy Theory of Change, created to measure diplomacy activities and advocacy tactics such as public awareness campaigns, communication and messaging, public polling, along with other FPDS funds (for instance, PIF, NIF, NAPP).

Based on this theory of change, initiatives can achieve 1 out of 3 possible types of desired changes, placed on a continuum, starting with awareness, developing into willingness and leading to action. The ultimate goal of advocacy tactics is to generate change on a specific foreign policy priority.

The evaluation found several misalignments between the MCF’s objectives and the advocacy outcomes and intended beneficiaries that take various forms, including:

- One of the MCF’s objectives (access) is not directly accounted for nor measured through specific indicators.

- There are different types of direct beneficiaries: Canadian artists and cultural organizations for MCF, and key foreign audiences (decision makers and influencers) for the Advocacy Theory of Change.

- There is a lack of recognition of additional outcomes achieved by cultural initiatives.

International best practices — objectives of cultural diplomacy

Like-minded countries define cultural diplomacy as a soft power approach supporting public diplomacy strategies, while also promoting their arts and culture and increasing the country’s attractiveness.

The following 3 cultural diplomacy goals are common to reviewed countries:

- increase knowledge and attractiveness of the country

- promote culture and cultural interactions and expanding markets (for some countries this includes language and exchange programs)

- enhance mutual understanding and positive relationships with other countries

Internal documents do not build any explanatory bridges between MCF’s objectives and the Diplomacy and Advocacy Theory of Change outcomes, which leaves them open to missions’ interpretation. In order to facilitate measuring the MCF results, the evaluation created a theory of change at the intersection of the MCF’s objectives and advocacy outcomes, including possible assumptions (see Annex 2).

In line with international best practices, the evaluation found that MCF’s objectives and results go beyond pure advocacy purposes. Consequently, the current advocacy framework and indicators are limitative for demonstrating the success of cultural initiatives and their potential outcomes.

Many interviewees indicated that it would be short-sighted to simply equate the MCF to an advocacy tool, used for achieving foreign policy priorities. Instead, the MCF’s objectives should be broader and inclusive of aspects such as building relations and partnerships, and leveraging opportunities organically, increasing Canada’s visibility and awareness of Canadian values abroad, promoting Canada’s culture and Canadian artists, including their economic prosperity through increased access to international markets. Some of these areas are already acknowledged in the MCF’s objectives, but they are not accurately measured.

Achieving cultural diplomacy objectives takes time and quantitative indicators do not always do them justice, nor are they the most appropriate for measuring success. The descriptive narrative of an initiative’s results is often considered more relevant as it captures outcomes that cannot be currently accounted for. At the same time, the quantitative results of cultural initiatives may often be relative and difficult to estimate:

- It is impossible to determine if the audience attending a cultural event was engaged or influenced without surveying them.

- The number of decision makers and influencers attending large cultural events is difficult to estimate and many times independent of the missions’ networking efforts.

- A large audience of students is not equivalent to a few top influencers attending an event.

- Information on audiences attending a specific event is not always available.

- Social media indicators such as the number of tweets or new followers are considered irrelevant and difficult to link to specific cultural initiatives.

The qualitative analysis of a sample of completed projects confirmed interviewees’ feedback and revealed other limitations of the current framework in measuring the results of cultural initiatives. For instance, within the current advocacy model, initiatives can only be aimed at influencing one type of audience (targeted or non-targeted) and contribute to the achievement of only one desired change (awareness, or willingness, or action). Contrary to this single-focused precondition, 25% of the 2017/18 reviewed projects and 34% of the 2018/19 reviewed projects resulted in reaching both targeted and non-targeted audiences. Concurrently, 15% of the total 2017/18 and 2018/19 reviewed initiatives contributed to achieving more than one desired change, which could not be reflected through the current Strategia categories.

Project Assessment Process and Funding Allocation

NMS has not established a formal project assessment and review process nor clear criteria for the current two-tier funding allocation to missions.

Current MCF guidelines include little information on the eligibility criteria and no reference to a possible breakdown of available funding into annual allocations and a project-based competitive process. The evaluation found that vague guidelines and eligibility criteria, as well as the absence of a formal project assessment process, have led to decreased transparency in the MCF’s administration and possible inequalities in funding allocations to missions.

The MCF does not have a formal project assessment and review process

A formal project assessment committee was deemed ineffective as it could hinder the MCF’s flexibility and increase paperwork in the context of scarcity of human resources. Furthermore, no feedback is provided to missions at the end of the fiscal year on the results achieved, other than making sure reporting through Strategia is completed.

The analysis of a sample of reviews made by advocacy strategists to planned projects as part of the annual Strategia planning cycle in 2018/19 and 2019/20 revealed inconsistent and limited comments, the large majority being related to possible re-profiling of projects to other funds (for instance, PIF, ITSF or NAPP) or follow-up requests with NMS for potential MCF funding. For example, in 2018/19, only 11% out of a total of 235 planned projects in 3 regions (Asia, South America and Caribbean, North America) were provided with comments, mainly related to non-eligibility to the MCF (for instance, not supporting Canadian artists or proposing a type of activity not covered by the MCF).

Several interviewees from missions that submit MCF projects as part of the project-based competitive process deemed the assessment mechanism unclear and lacking in transparency. The length of the decision-making process for the competitive process is considered to be a source of uncertainty that places missions in a reactive position and potentially creates frustration among local partners. Furthermore, until recently, because of the lack of an automatic notification in Strategia, missions had to directly inform NMS when new planned projects were added to Strategia. In some cases, a lot of back and forth was required to have projects reviewed and approved by NMS.

Funding allocation is a two-tier system that is not supported by clear criteria

According to MCF guidelines, planned initiatives should be reviewed in a competitive and comparative context, based on the MCF’s objectives and eligibility criteria.

However, the evaluation found that the funding allocation mechanism is a two-tier system, dividing missions between those receiving annual allocations at the beginning of the fiscal year, and those participating in a project-based competitive process. A few interviewees were either not aware of the existence of annual allocations or believed that allocations were available to only a few large centres such as London, Paris and New York.

Missions that receive annual allocations are equally eligible to submitting requests for additional projects throughout the year. For example, in 2018/19, 24 missions received 32% of the total MCF actual funding through annual allocations. In fact, the total actual funding received by these missions counted for more than half of the total funding available to missions in 2018/19 (58%).

According to internal interviewees, the criteria for funding allocation include priority given to missions from important cultural centres, with capacity acknowledged by HQ as being well-established and having a good understanding of cultural diplomacy. The evaluation was not able to determine the extent to which these informal criteria were applied: among missions that received allocations, several seemed to have a rather limited capacity to deliver cultural initiatives.

Strategia Reporting

Strategia data-quality issues and gaps impede the capacity to accurately measure MCF results and limit the accountability for actual expenditures.

Data and project reviews identified significant data-quality issues related to reporting on cultural initiatives due to performance measurement limitations, but also misinterpretation of reporting categories by missions and a lack of HQ oversight of initiative results. Added to the Strategia related gaps, these inaccuracies alter the reliability of data on the results of MCF initiatives and consequently their use for reporting purposes. These gaps also limit the accountability related to actual expenditures.

Strategia data-quality issues

A closer look at data reporting for cultural initiatives revealed the existence of numerous outliers, significantly skewing the overall results. In some cases, outliers originated from the same missions, showing a lack of understanding of reporting requirements. For example, in 2018/19, there were 28,622 targeted audiences privately supporting initiatives intended to influence key foreign audiences’ willingness, among which 56% were reported by the same mission.

Examples of Strategia KPIs

Awareness; targeted audience

# of audience engaged: specific influencers and/or decision makers that have been engaged (involves making advocacy case through one-on-one, group meetings or advocacy initiatives)

# of follow up engagements: secondary interactions with the target audience as a result of the initial engagement indicating interest in Canada’s position

Willingness; targeted audience

# of audience publicly supporting Canada’s position: measures the number of specific influencers and/or decision makers who take action in alignment with, or support of Canada’s position

The same year, initiatives aimed at increasing or maintaining awareness led to 2,889 follow-ups by targeted audiences, with 3 missions reporting for a total of 81.5% of them. In 2019/20, the same indicator was largely skewed by one mission reporting 104,000 follow-ups out of a total of 105,050. Furthermore, there is little to no indication of the type of follow-up or public/private support by targeted foreign audiences in the descriptive explanation of initiatives.

The project review identified other examples of data-quality issues (for example, reporting non-targeted audiences as targeted; reporting the total audience of major festivals with significant and complex multi-funding sources for cultural initiatives that were only a parts of these cultural events; misidentification of initiatives’ desired change or type of audience; linkage to secondary categories unrelated to the scope of the initiative). Another aspect of the data-quality issues is related to missing performance data in early years of the MCF: 47% of initiatives completed in 2016/17 and 33% of initiatives completed in 2017/18 had no key performance indicators entered.

Strategia system-related gaps

The evaluation identified Strategia system-related gaps impacting accountability and the capacity to determine MCF’s contribution to achieving results. These gaps include the fact that actual funding is not directly tied into budget controls, and funding from other departments or local partners is largely missing. Furthermore, Strategia does not allow for a clear account of the use of the actual MCF funding as missions report inconsistently on planned funding (15% of completed projects do not include MCF planned amounts).

Strategia also does not allow for reporting on multi-year initiatives, forcing the breakdown of larger events or objectives into separate smaller initiatives, preventing missions from telling the whole story of the progress made in achieving planned objectives.

Actual MCF Expenditures and Mission Capacity

Inconsistent levels of annual funding and insufficient regional training and resources may impede the effective delivery of MCF initiatives by missions.

As shown in Table 2, during the evaluation period, NMS successfully secured additional funding sources to the $1.75 million annual envelope (re-profiling of salary funds in 2016/17, increased resources in support of Canada 150 in 2018/19, and departmental surplus in 2018/19 and 2019/20).

| 2016/17 | 2017/18 | 2018/19 | 2019/20 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCF Actual Funding | $2,091,838 | $5,247,423 | $4,008,019 | $6,015,292 |

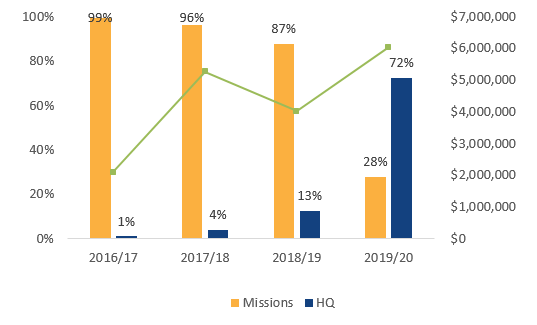

During the same period, the evaluation observed an increased trend in the allocation of MCF funds by HQ for implementing major joint ventures with federal partners. As shown in Figure 4, in 2019/20, only 28% of the total actual funding was dedicated to implementing missions-led cultural initiatives compared to 87% in 2018/19 and 96% in 2017/18.

Interviews revealed that, even in the case of missions receiving annual allocations, the inconsistent level of annual funding led to increased uncertainty on the capacity to deliver cultural initiatives and fear of jeopardizing existing partnerships and engagements.

Figure 4. HQ and missions funding allocation

Text version

| Fiscal years | Missions | HQ |

|---|---|---|

| 2016/17 | 99% | 1% |

| 2017/18 | 96% | 4% |

| 2018/19 | 87% | 13% |

| 2019/20 | 28% | 72% |

Insufficient resources for delivering MCF initiatives at missions

Interviewees from missions with new LES positions and LES having an experience in cultural diplomacy prior to MCF, expressed mixed views on the extent to which current resources are adequate because of the size and strategic importance of the covered region, and the volume of requests for cultural diplomacy initiatives (for example, New York, Mexico, Rome, Shanghai).

In order to increase missions’ capacity to deliver cultural initiatives, several regions, currently understaffed, but with high potential in terms of supporting foreign policy priorities, could benefit from new LES positions: Middle East; Africa (Nairobi; the African Francophone region), South America (Colombia), Europe (Brussels, Ankara), Asia (Seoul).

Training opportunities offered by NMS

In early stages of the MCF, training on the MCF and cultural diplomacy was not available and missions had to learn on the job, as part of a lengthy process. During the last two years, missions have had access to increased training and presentations, through multiple channels and venues, both in Canada and abroad.

Interviewees who participated in recent training sessions organized by NMS expressed high levels of satisfaction. They found the training not only a good learning opportunity, but also a networking enabler, allowing them to meet Canadian partners and exchange best practices.

However, several interviewees did not attend any training and expressed the need for further guidance and information on their roles related to cultural initiatives. FPDS staff from distant missions would like to benefit from regional training, adapted to their specific context and challenges, and be introduced to potential Canadian partners from the arts and culture sectors.

Challenges in Delivering Cultural Initiatives

Several challenges, including the current funding mechanism, affect the effective delivery of cultural initiatives by missions.

The evaluation revealed general challenges impacting the effective delivery of cultural initiatives by missions as related to the MCF’s funding mechanism, but also challenges specific to developing and/or remote countries.

The funding mechanism is the most significant challenge affecting the MCF’s delivery by missions

The current approach to contracts and procurement for cultural initiatives is considered to be administratively cumbersome, time consuming and less adapted to cultural initiatives. There were no specific templates for contracts and letters of agreement adapted to the requirements of cultural initiatives, and missions had to adapt existing ones based on their understanding, and at times, advice received from larger missions. In many cases, the MCF is used as a contribution to existing cultural events, but contribution agreements are not allowed.

Contracts for cultural initiatives between $10,000 and $89,600 are subject to approval review by Regional Contract Review Boards (RCRB). In addition, contracts above $25,000 are subject to a tender process, which is difficult to apply to cultural initiatives that have only one partner identified for one specific cultural event (for example, a book fair or a large festival). Missions do a lot of back and forth with RCRB, and the length of the approval process affects payments to providers (local partners), who have to pay up-front and be refunded later.

An analysis of MCF amounts used by missions to deliver cultural initiatives may reflect the challenges related to the current funding mechanism. As shown in Table 3, in 2018/19, almost 9 out of 10 initiatives used MCF amounts smaller than $10,000, requiring only a program manager’s approval. To streamline the process, suggestions include: upfront allocations and use of grants and contribution agreements on the model of the ones for international development projects.

| RCRB Approval Request | Actual MCF Funding | % of initiatives |

|---|---|---|

| Not subject to RCRB approval procedures | < $2 000 $ | 29 % |

| Program Manager | $2K to $10K | 59 % |

| RCRB – 1 member review | $10K to $28.9K | 11 % |

| RCRB – 3 members review & consultations with HQ | $29.8K to $40K | 0.5 % |

| RCRB – 3 members review & approval HQ | > $40K | 0.5 % |

Source: Strategia; RCRB Approval Requests

Some eligibility criteria are less adapted to developing and/or remote countries

The requirement to have Canadian artists identified by local partners in regions where they are less known limits the missions’ capacity to leverage cultural events in place. Furthermore, the lack of timely information on Canadian artists coming to a region, and the length of the Canada Council Arts grants approval process (MCF is often used to complement CCA funding) put pressure on the artists’ participation in cultural events and consequently hinder the delivery of planned cultural initiatives. In some developing countries, security issues may limit the willingness of Canadian artists to participate in cultural events.

Identifying solid local partners can be a challenge in developing countries, where resources are limited. For example, according to one interviewee, “The cultural fund had only one way of operating, designed for richer markets.” The controls on cultural activities and difficulty in focusing on culture in conflict regions are other potential obstacles to delivering cultural initiatives in some regions.

Conclusions

The evaluation of the Mission Cultural Fund found that NMS and missions built successful partnerships and collaborations and cultural initiatives contributed to achieving various outcomes, including increased access to foreign audiences and increased opportunities for Canadian artists.

Nevertheless, the evaluation identified a number of areas that should be further considered, as well as actions required in order to establish clear, equitable and transparent decision-making mechanisms and provide strategic guidance for the implementation of cultural initiatives.

What works well

- Demonstrated continued need for cultural diplomacy;

- Numerous collaborations and partnerships with local and Canadian partners to implement cultural initiatives that successfully contributed to promoting Canadian artists and organizations abroad;

- Cultural initiatives have a great potential to facilitate access to a broad range of audiences and provide Canadian artists with increased opportunities; and

- Many cultural initiatives contribute to achieving multiple outcomes.

What needs further consideration

- In order to reinforce the cultural diplomacy-development nexus, identify concrete opportunities for collaboration with the international assistance business line;

- Explore options for adapting the current financial mechanism to cultural initiatives;

- Conduct consultations with missions (particularly the ones that have not implemented cultural initiatives) to identify specific needs and multiply learning opportunities for missions in distant regions; and

- Work with Strategia to adapt the system in order to accurately, consistently and adequately measure the results of cultural initiatives.

Where action is required

- Elaborate a theory of change and performance indicators specific to MCF;

- Clarify roles, responsibilities and accountabilities related to the business process of delivering MCF at HQ and missions;

- Establish a formal governance structure and decision-making mechanisms related to project assessment and funding allocation; and

- Elaborate an evidence-based strategic guidance, aligned with the department’s current priorities to guide the delivery of the MCF by missions.

Recommendations

It is recommended that NMD undertake the following actions based on the findings from this evaluation:

- Establish a formal governance structure for decision making, and clearly articulated roles and responsibilities for internal and external stakeholders involved in the administration and delivery of the MCF at HQ and missions abroad. This may include formalizing interdepartmental and intradepartmental collaboration to ensure that objectives, policies and programs are coordinated, and areas of concentration and possible duplication are identified.

- Elaborate a strategic framework for the MCF, aligned with the department’s current foreign policy and regional priorities. This may include considering international best practices in like-minded countries and introducing a specific stream aimed at supporting cultural initiatives in developing countries and ultimately increasing the diplomacy-international aide nexus; conducting extensive consultations with missions (including missions that did not implement cultural initiatives) to identify capacity challenges and/or training needs.

In support of this framework, develop operational guidelines and tools as well as a formal project assessment process to ensure transparent and equitable funding allocation. - Adapt the FPDS theory of change and performance indicators to support results reporting, reflect the contributions of cultural initiatives to achieving the MCF’s objectives and create monitoring mechanisms for their implementation.

Management Response and Action Plan

Recommendation 1

Establish a formal governance structure for decision making, and clearly articulated roles and responsibilities for internal and external stakeholders involved in the administration and delivery of the MCF at HQ and missions abroad. This may include formalizing interdepartmental and intradepartmental collaboration to ensure that objectives, policies and programs are coordinated, and areas of concentration and possible duplication are identified.

Management Response

Agreed.

- NMS/NMD will revaluate and implement the most appropriate governance structure.

- NMS will consult key sectors at PCH and key portfolio agencies to feed into the yearly cultural diplomacy framework. There had already been meetings and a framework built with PCH and Canada Council for the Arts at the DM level. Absence of follow up by senior management stopped the process. We will suggest modifications to this framework to renew the consultations.

- NMS will clarify, define and share roles and responsibilities for internal and external federal stakeholders involved in the delivery of the MCF.

| Action Plan | Responsibility | Time Frame |

|---|---|---|

| Evaluate the most appropriate governance structure for the MCF | NMD/NMS | Fall/Winter 2020 |

| Renew a consultation process with PCH and its portfolio agencies | NMS | Fall/Winter 2020 |

| Implement governance structure | NMD/NMS | Winter/Spring 2021 |

| Develop and share documents outlining roles and responsibilities | NMS | Winter 2021 |

Recommendation 2

Elaborate a strategic framework for the MCF, aligned with the department’s current foreign policy and regional priorities. This may include considering international best practices in like-minded countries and introducing a specific stream aimed at supporting cultural initiatives in developing countries and ultimately increasing the diplomacy-international aide nexus; conducting extensive consultations with missions (including missions that did not implement cultural initiatives) to identify capacity challenges and/or training needs.

In support of this framework, develop operational guidelines and tools as well as a formal project assessment process to ensure transparent and equitable funding allocation.

Management Response

Agreed.

- A cultural diplomacy framework will be elaborated, discussed and validated by GAC governance, and shared with missions to align the MCF to GAC’s foreign policy and regional priorities.

- NMS will provide additional operational guidelines and tools to guide missions; to be added to the existing MCF guidelines and cultural diplomacy hub.

- While MCF projects are already assessed by NMS mission liaison officers in consultation with relevant stakeholders, NMS will explore creating a more formal assessment process to be delivered through Strategia, or through other means.

- NMS will continue to ensure that MCF operations remain nimble, support innovation, increase productivity while strengthening accountability processes in accordance with Canada’s Red Tape Reduction Plan.

| Action Plan | Responsibility | Time Frame |