Evaluation of Diplomacy, Trade and Development Coherence in the Latin American and Caribbean Region

Prepared by Diplomacy, Trade and Corporate Evaluation Division (PRE)

Global Affairs Canada

January 2021

Table of Contents

- Abbreviations

- Executive summary

- Background

- Evaluation scope and methodology

- Findings

- Conclusions

- Recommendations and considerations

- Annexes

Abbreviations

- ADM

- Assistant deputy minister

- BWIT

- Business Women in International Trade

- CBS

- Canadian-based staff

- CFLI

- Canada Fund for Local Initiatives

- CIDA

- Canadian International Development Agency

- CSO

- Civil society organization

- CSR

- Corporate social responsibility

- DFAIT

- Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade

- DG

- Director general

- FPDS

- Foreign Policy and Diplomacy Service

- FTE

- Full-time equivalent

- GAC

- Global Affairs Canada

- HOA

- Head of aid

- HOC

- Head of cooperation

- HOM

- Head of mission

- HQ

- Headquarters

- LAC

- Latin America and the Caribbean region

- LDC

- Least-developed countries

- LES

- Locally engaged staff

- MACCIH

- Mission to Support the Fight Against Corruption and Impunity in Honduras

- MSR+

- Management summary report

- NGM

- Americas Branch

- NDD

- Central America and Caribbean Bureau

- NDS

- Strategic Planning, Policy and Operations Division

- NLD

- South America and Inter-American Affairs Bureau

- O&M

- Operations and maintenance

- OAS

- Organization of American States

- ODAA

- Official Development Assistance Act

- OECD

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

- OECD-DAC

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development – Development Assistance Committee

- OGD

- Other government department

- PRD

- Evaluation and Results Bureau

- SDGs

- Sustainable Development Goals

- WGM

- Sub-Saharan Africa Branch

Executive summary

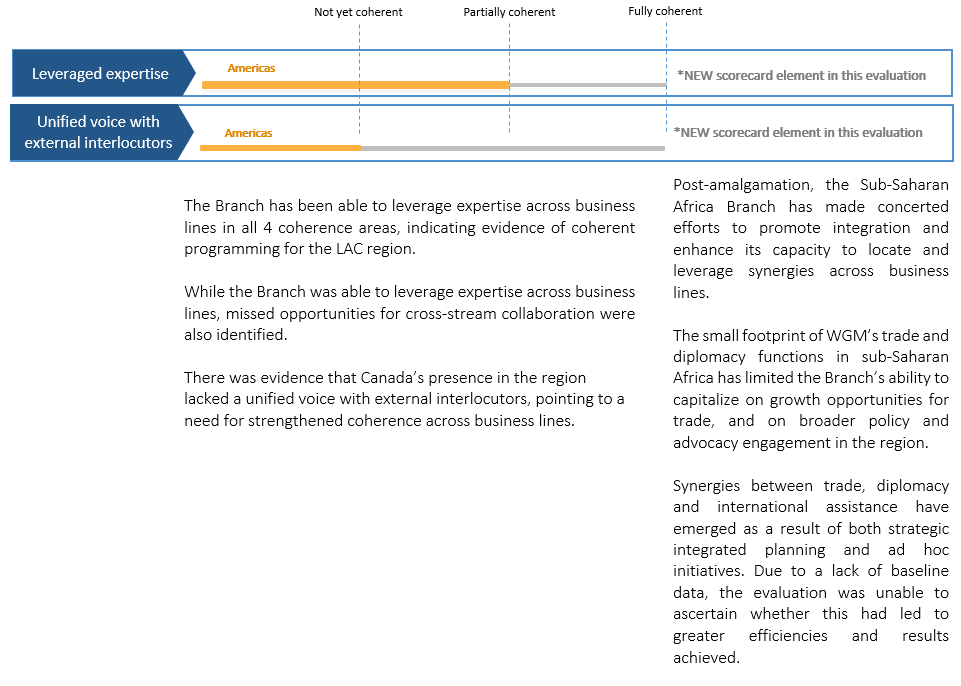

This evaluation examined Canada’s diplomacy, trade and development coherence in the Latin American and the Caribbean (LAC) region during the period from 2013-14 to 2019-20. The evaluation is part of the Five-Year Departmental Evaluation Plan, and is the second in a planned suite of geographic-branch evaluations of diplomacy, trade and development coherence. This report presents the evaluation findings, conclusions and recommendations. Considerations to foster horizontal learning across the department are also included.

Coherent programming and results

The evaluation found that the Americas Branch has leveraged expertise across business lines in all coherence areas between diplomacy, trade and development, with evidence of coherent programming in the LAC region. However, missed opportunities for further cross-stream collaboration were also identified. There was also evidence that Canada’s presence in the region lacked a unified voice with external interlocutors, pointing to a need for strengthened communication and coordination across business lines.

Organizational coherence

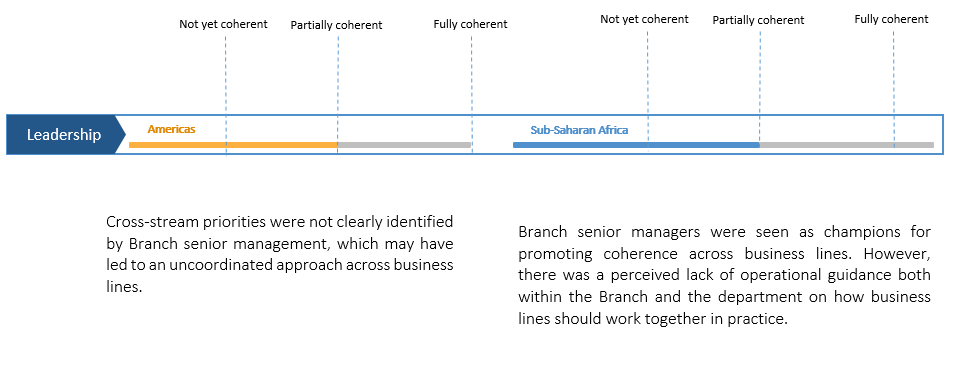

The evaluation found that cross-stream priorities for the LAC region were not clearly identified by Americas Branch senior management, which may have led to an uncoordinated approach across business lines for Canada’s international engagement with countries in the region. Additionally, a lack of formal communication mechanisms to increase cross-stream collaboration has led to a limited understanding of the priorities and activities of other business lines.

Departmental policies governing diplomacy, trade and development were found to be aligned in thematic areas of gender equality, economic participation and prosperity, democratic participation and inclusive governance, peace and security, and human rights and dignity, presenting opportunities for cross-stream coherence. However, the department’s multiple planning and reporting tools impeded cross-stream coherence in the Americas Branch.

Delivery models to strengthen coherence

The evaluation found that while some aspects of the current Americas Branch organizational structure fostered coherence, the complexity of the structure presented barriers to cross-stream collaboration.

Summary of recommendations

- Improve the strategic planning process across diplomacy, trade, and development

- Implement formal cross-stream communication mechanisms to increase understanding of the roles and responsibilities across the business lines and to leverage expertise of diplomacy, trade and development

- Review the current organizational structure to streamline the complexity that impedes coherence of diplomacy, trade and development and implement models that promote cross-stream coherence

Background

Background: Framing coherence

Coherence at Global Affairs Canada

In the years since the amalgamation, in 2013, of the former CIDA and DFAIT, senior management at Global Affairs Canada (GAC) has been expecting more coherent policy and programming across diplomacy, trade and development. To examine coherence more strategically, the first in a planned suite of regional coherence evaluations, focused on sub-Saharan Africa, was conducted in 2019. The evaluation of the Americas is the second in the suite, and builds on the work undertaken so far in the department. Further regional coherence evaluations are planned for 2020 and 2021.

Opportunities for coherence

Diplomacy, trade and development intersect in several policy and programming areas. This evaluation examines the areas where these 3 business streams converge. Four areas were of interest, featuring the convergence between 1) diplomacy and development; 2) diplomacy and trade; 3) development and trade; and 4) all 3 business lines. The diplomacy business line, delivered by Foreign Policy and Diplomatic Services (FPDS) staff, is truncated to “diplomacy” in this report.

Four coherence areas:

Text version

Diplomacy & Development: 1

Diplomacy & Trade: 2

Development & Trade: 3

Diplomacy, Development & Trade: 4

Building on previous program evaluations

The framework for evaluation coherence was first established by an evaluation of coherence across sub-Saharan Africa. This first evaluation identified efforts toward achieving organizational coherence, potential areas for collaboration and several department-wide challenges related to coherence. The evaluation also developed scorecards for 6 organizational elements that enable coherence: leadership, roles and responsibilities, organizational structure, communication, systems and processes, and policy alignment. These elements helped to inform the framework used by the evaluation team in assessing coherence in the LAC region.

Additionally, a review of all evaluation reports completed by the Evaluation and Results Bureau (PRD) between 2015 and 2019 identified 20 evaluations with findings related to coherence. Coherence-related best practices and lessons learned from this review were also used to inform the framework for assessing coherence in the LAC region.

Primary objectives of CIDA-DFAIT amalgamation

Based on a review of internal documents, the following objectives of the 2013 amalgamation process were identified:

- to achieve greater policy coherence on foreign, trade and development priority issues

- to leverage complementary strengths, and see the work of diplomacy, trade and development as relevant for work across all 3 business lines

Source: Government of Canada, Economic Action Plan 2013 (pp. 240-241) https://www.budget.gc.ca/2013/doc/plan/budget2013-eng.pdf

Background: Branch profile

Organizational structure at Headquarters

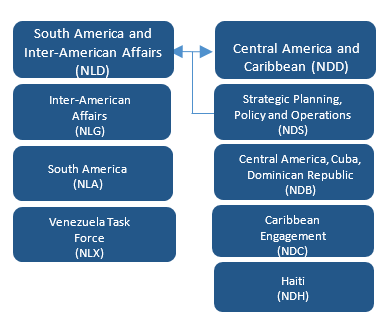

The Branch is divided into 5 bureaus, 2 of which support the LAC region:

- The South America and Inter-American Affairs Bureau (NLD) provides support to 14 missions in South America, as well to as Inter-American Affairs, which provides programming across the entire LAC region.

- The Central America and Caribbean Bureau (NDD) provides support to 14 missions in Central America and the Caribbean. The Bureau houses the strategic policy and operation division that provides support to both NLD and NDD. The Bureau also includes a division responsible for Haiti.

Figure 1. Bureaus responsible for the LAC region

Text version

Bureaus:

- America and Inter-American Affairs (NLD)

- Central America and Caribbean (NDD)

- Strategic Planning, Policy and Operations (NDS) (supports both bureaus)

Under NLD:

- Inter-American Affairs (NLG)

- South America (NLA)

- Venezuela Task Force (NLX)

Under NDD:

- Central America, Cuba, Dominican Republic (NDB)

- Caribbean Engagement (NDC)

- Haiti (NDH)

Complexity of Americas Branch

The Americas Branch has a complex structure, covering North, Central and South America, as well as the Caribbean. The Latin American and Caribbean (LAC) region assessed in this evaluation is comprised of South America, Central America and the Caribbean sub-regions, each of which has unique and diverse country-level priorities and corresponding programming for each country context.

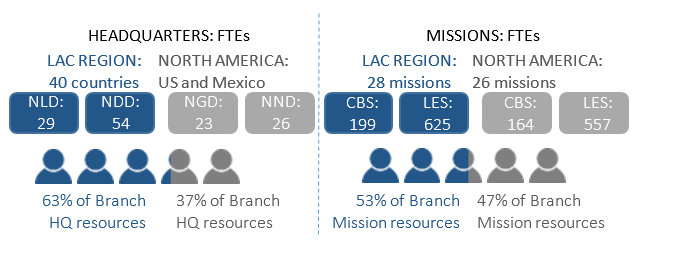

Human resources

In the Americas Branch, 770 full-time equivalent (FTE) resources are responsible for North America (United States and Mexico) and 907 FTEs are responsible for the LAC region. The majority of staff are located at mission, with only 10% of North America staff and 6% of LAC region staff located at headquarters.

Of staff responsible for the LAC region, 2 bureaus provide support to 40 countries in the LAC region through 28 mission offices. The bureau for Central America and the Caribbean (NDD) is considerably larger than the bureau for South America (NLD), both at headquarters and at missions.

Figure 2. Number of FTEs in LAC Region and North America, broken down by Headquarters and Missions

Text version

Number of FTEs in LAC region and North America, broken down by headquarters and missions

Headquarters: FTEs:

LAC region: 40 countries

- NLD: 29

- NDD: 54

- 63% of Branch HQ resources

North America: US and Mexico

- NGD: 23

- NND: 26

- 37% of Branch HQ resources

Missions: FTEs:

LAC region: 28 missions

- CBS: 199

- LES: 625

- 53% of Branch mission resources

North America: 26 missions

- CBS:

- LES:

- 47% of Branch mission resources

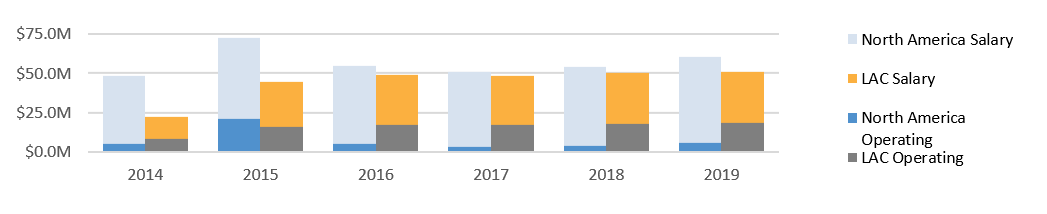

Financial resources

The Americas Branch manages all operations and maintenance (O&M) and salary budgets at HQ and at missions in the Americas. In the LAC region, both O&M expenditures and salary expenditures increased from 2014-15 to 2015-16, and have remained fairly consistent since then.

Figure 3. $ million ($Can) of salary and operations and maintenance, broken down by LAC region and North America

Background: Regional funding

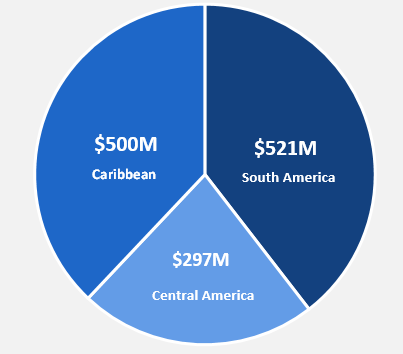

Figure 4. $ million ($Can) of GAC funding in the LAC region, broken down by sub-region

Funding across the LAC region for all business lines from 2014-15 to 2018-19 was higher in South America ($521 million) and the Caribbean ($500 million) than in Central America ($297 million).

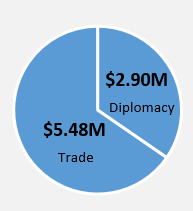

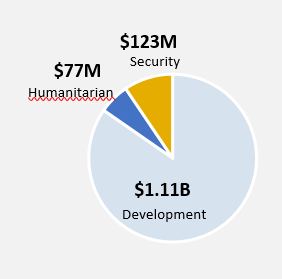

Figure 5. $ million ($Can) of GAC funding in the LAC region, broken down by business line

(diplomacy and trade shown separately for scale purposes)

Funding for trade initiatives ($5.48 million) was nearly double funding for diplomacy initiatives ($2.90 million) from 2014-15 to 2018-19.

Funding for development ($1.11 billion), humanitarian ($77.0 million), and security ($123 million) programming totalled $1.31 billion from 2014-15 to 2018-19.

Global Affairs Canada funding in the LAC region

From 2014-15 to 2018-19, funding in the LAC region totalled $1.32 billion, corresponding to a yearly average of $264 million. During that period, the bulk of departmental funding was for development assistance, totalling $1.11 billion, with security programming disbursements totalling $123 million, humanitarian assistance totalling $77 million, trade initiatives totalling $5.48 million, and diplomacy initiatives totalling $2.90 million.

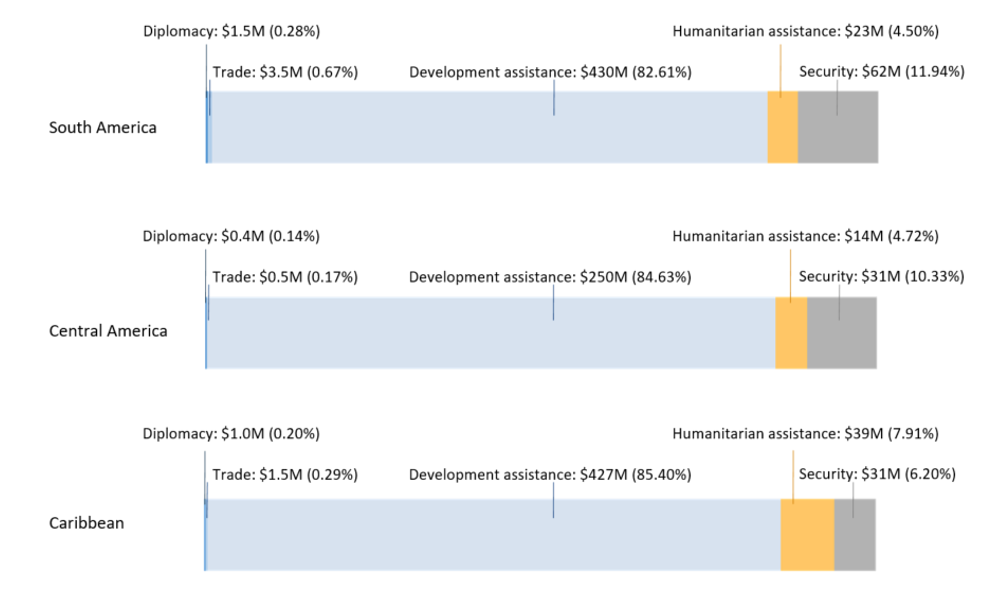

Figure 6. $ million ($Can) of GAC funding in the LAC region, broken down by business line in each sub-region (% of funding for each business line in sub-region)

Text version

South America:

- Diplomacy: $1.5M (0.28%)

- Trade: $3.5M (0.67%)

- Development assistance: $430M (82.61%)

- Humanitarian assistance: $23M (4.50%)

- Security: $62M (11.94%)

Central America:

- Diplomacy: $0.4M (0.14%)

- Trade: $0.5M (0.17%)

- Development assistance: $250M (84.63%)

- Humanitarian assistance: $14M (4.72%)

- Security: $31M (10.33%)

Caribbean:

- Diplomacy: $1.0M (0.20%)

- Trade: $1.5M (0.29%)

- Development assistance: $427M (85.40%)

- Humanitarian assistance: $39M (7.91%)

- Security: $31M (6.20%)

Evaluation scope and methodology

Evaluation scope and objectives

Evaluation scope

The evaluation assessed the coherence of business lines under the management authority of the Americas Branch, particularly the bureaus responsible for the Latin American and Caribbean (LAC) region. The coherence of these business lines was assessed in relation to priorities of each of the 3 sub-regions: South America, Central America and the Caribbean. The reference period assessed was fiscal years 2013-14 to 2019-20.

The evaluation did not consider the interaction between the Americas Branch and other functional or corporate branches within the department that share responsibility for the LAC region. Multilateral (including humanitarian) assistance, partnership and international security programming were therefore not included in the evaluation scope. Consular services and internal services within missions were also outside of the evaluation scope.

Evaluation approach

The Americas Branch requested to be second in the planned suite of geographic-branch coherence evaluations, in part to inform an organizational review being conducted by the Branch. The Branch is complex, with a focus on trade in some countries, bilateral and/or regional development programming in others, and varied diplomatic relations across the region. Because of this complexity, the evaluation aimed to identify examples of success stories that can be replicated elsewhere, as well as areas where coherence can be further strengthened.

Other evaluations previously or concurrently conducted during the same time period also assessed aspects of coherence in the Americas. The LAC coherence evaluation therefore included evidence from other evaluations, where possible, to ensure efficient use of available evidence and resources—a novel approach to assessing coherence.

| Evaluation issue | Question |

|---|---|

| Coherent programming and results | Q1. To what extent is LAC programming coherent across diplomacy, trade and development? Where do opportunities exist for strengthening policy and program linkages between business lines? How does coherence contribute to better program results? |

| Organizational coherence | Q2. How well established are key organizational elements that enable coherence across diplomacy, trade and development in the Americas Branch? |

| Delivery models to strengthen coherence | Q3. To what extent do the current program delivery models in the LAC region ensure coherent support of bilateral relationships in the region? What, if any, alternative delivery models would strengthen coherence? |

Definition of coherence

For the purposes of this evaluation, the team built on the definition developed by the first geographic-branch coherence evaluation, as well as the recent definition developed by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) - Development Assistance Committee (DAC). Coherence was therefore defined as:

“Work across diplomacy, trade and development business lines with an intent to coordinate decisions and avoid working at cross purposes, so that expertise is leveraged across business lines, a unified voice is portrayed for Canada, and better program and policy results are achieved in the region.”

Methodology

The evaluation used a mixed-method approach, where data was collected from a range of sources to ensure multiple lines of evidence when analyzing data and formulating findings. While examples are used for illustrative purposes, each finding has been triangulated using evidence from a mix of quantitative and qualitative data. Four main methods were used to collect data, and 3 methods were used to analyze data—each described below.

Data collection

Document and financial review

Review of internal Global Affairs Canada documents and financial information:

- policy documents

- planning and strategy documents

- annual reports

- briefing notes and memos

- evaluations, audits and reviews

- financial and statistical information generated from SAP, Strategia, MSR+, and TRIO2 databases

Literature review

Review of academic literature, partner publications, and other secondary documentation, including:

- peer-reviewed articles on key elements that enable coherence

- publications by international organizations such as the World Bank, OECD and United Nations on their coherence across business lines

- subject-matter authority reports and publications on LAC region priorities

Interviews

Semi-structured individual and small group interviews:

- current and past GAC Branch staff at the executive management level

- like-minded country representatives

- other government department staff

- representatives for LAC region governments and trade and development civil society organizations

Online survey

Internal GAC online survey:

- all Branch staff at HQ and at missions with responsibility for diplomacy, trade and/or development in the LAC region

- generated 134 completed questionnaires, with a raw response rate of 30.5%, predominantly at the working level

- used to validated themes that emerged from the interviews, and assessed respondent perceptions of the current state of organizational coherence in the Branch

Data analysis

Theory of change

Development of a theory of change to analyze impact of coherence:

- focus group discussions with all business lines and LAC sub-regions in the Americas Branch

- relevant academic literature

- evidence collected from this evaluation

Sub-regional profiles

Development of profiles for South America, Central America and the Caribbean based on country-level analysis

- document and data review

- literature review

- key stakeholder interviews

- online survey

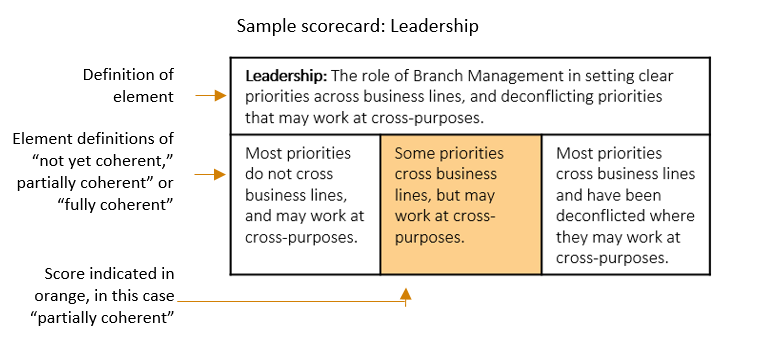

Coherence Scorecards

Refinement of coherence evaluation scorecards to assess organizational elements that enable coherence (Branch-level and department-level) and expected outcomes determined by theory of change (see Annex A):

- document and data review

- key stakeholder interviews

- online survey

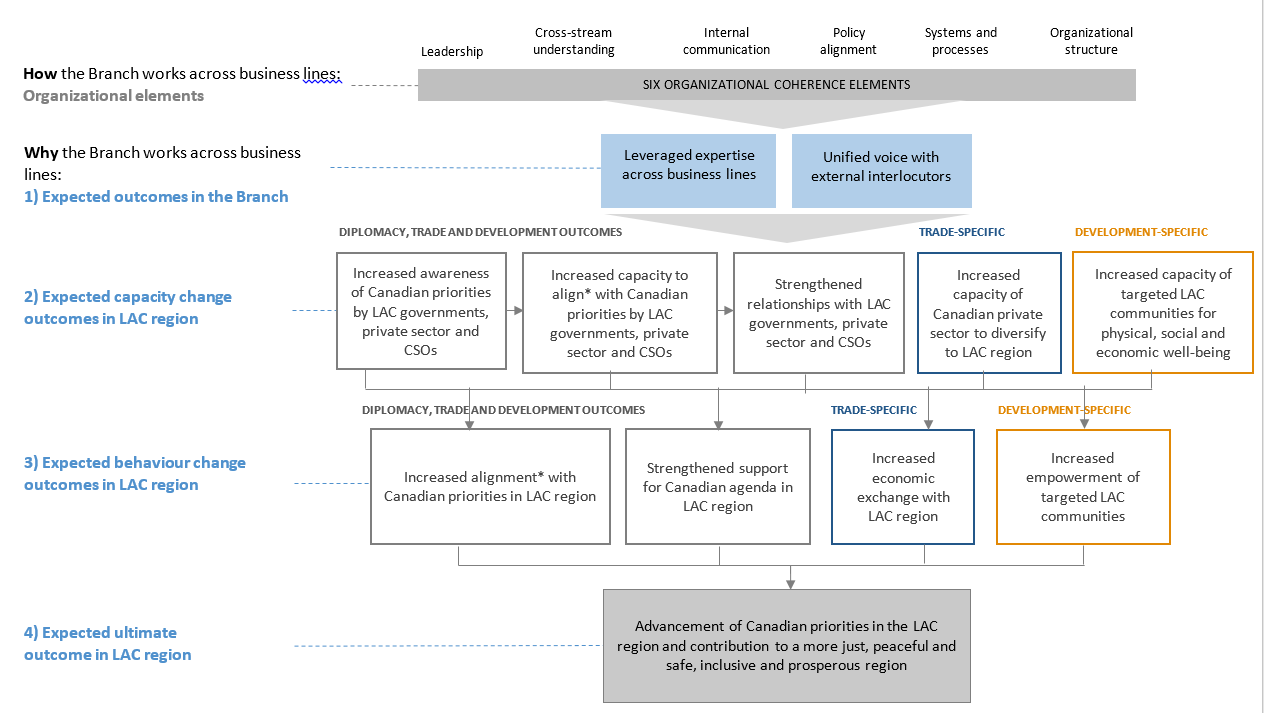

How geographic branches work across business lines

Branch organizational elements:

- Leadership

- Internal communication

- Organizational structure

- Cross-stream understanding

Departmental organizational elements:

- Systems & processes

- Policy alignment

Why geographic branches work across business lines

Coherence expected outcomes:

- Leveraged expertise across business lines

- Unified voice with external interlocutors

- Better achievement of results

Evaluation limitations and mitigation measures

| Limitations | Mitigation measures |

|---|---|

Varying interpretations of coherence:

|

|

Link between coherence and amalgamation:

|

|

Shared responsibility for coherence across branches:

|

|

Findings

Coherent programming and results

1. The Branch has been able to leverage expertise across business lines in all four coherence areas, indicating evidence of coherent programming for the LAC region

The evaluation team developed a theory of change to determine the expected benefits of coherent programming across diplomacy, trade and development. Leveraged expertise was determined as an expected outcome of coherence. The Branch was therefore assessed for its ability to leverage expertise across business lines and the extent to which cross-stream expertise was shared in each coherence area. Overall, the Branch has been able to leverage expertise across business lines in all 4 coherence areas, demonstrating coherent programming for the LAC region.

After assessing the Branch’s ability to leverage expertise across business lines, concrete examples were documented across the LAC region. These examples were noted in all 4 coherence areas between diplomacy, trade and development. Notable examples in each coherence area are presented below.

Diplomacy – Trade – Development

- The response to the Venezuela crisis: At the Embassy of Canada to Peru, the crisis implicated FPDS staff given the diplomacy priority to address the crisis, while development and trade staff worked to better integrate Venezuelan migrants into Peruvian society. Collaboration took place regularly across all 3 business lines in the effort to address evolving needs. This cross-stream work included consistent communication, joint meetings with external stakeholders and discussions about how to complement the respective work of each business line.

- Corporate social responsibility (CSR): At the Embassy of Canada to Colombia, a cross-stream committee launched in 2018 to address CSR-related issues provided a formal communication mechanism across business lines. A responsible-business-conduct roadmap was also developed. CSR-related efforts were cited throughout this coherence evaluation as a strong example of coherence.

- The oil sector: When oil was discovered in Guyana, staff from each stream at Canada’s High Commission in Guyana understood the role they could each play in building the Guyanese oil industry. Staff accessed funding through the mechanisms available to their respective business lines, and leveraged cross-stream expertise to provide regulatory advice for the nascent industry while developing commercial opportunities with Newfoundland.

- Women in trade: At the Embassy of Canada to Uruguay, staff from all 3 business lines collaborated to implement a Canada Fund for Local Initiatives project to enable girls of African descent to gain employment skills.

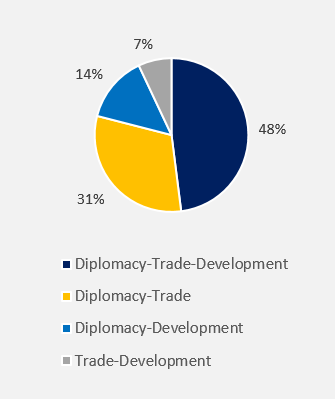

Interview mentions of leveraged expertise

During interviews, Branch staff provided examples of leveraged expertise across business lines. Each reference, or “mention,” was documented along with the coherence area in which it took place.

Figure 8. Percentage of interview mentions of cross-stream leveraged expertise, broken down by coherence area

Text version

Diplomacy-Trade-Development: 48%

Diplomacy-Trade: 31%

Diplomacy-Development: 14%

Trade-Development: 7%

Nearly half of all documented mentions took place in the diplomacy-trade-development area, while nearly a third took place in the diplomacy-trade area. The least number of mentions was recorded for the trade-development area.

Coherent programming and results

Diplomacy – Trade

- Market access for least-developed countries (LDCs): An item in the 2017 Government of Canada Budget referenced duties and LDC access preference for Haiti. This government priority allowed staff at the Embassy of Canada to Haiti to leverage expertise across diplomacy and trade business lines to jointly focus on capacity building, training and advocacy activities.

- Education promotion: At the Embassy of Canada to Argentina, diplomacy and trade staff leveraged expertise to ensure education promotion to local students while also ensuring linkages with institutions, professors and researchers. Trade staff focused on building relationships with private institutions, while FPDS staff leveraged their network to focus on public universities.

- Cultural industries: As one of 2 leading cultural programs in the LAC region, the Embassy of Canada to Argentina was responsible for the majority of regional products and projects related to cultural promotion. Trade commissioners and FPDS officers collaborated to work with the Canada Council for the Arts, hold 2 cultural summits (in Ottawa in May 2018 and in Buenos Aires in June 2019), and promote regional Francophonie projects. As the sector was relatively new for trade, FPDS staff shared their expertise and network while trade commissioners took the lead on logistics and engaging the Department of Canadian Heritage.

- Women in mining: At the Consulate General of Canada in Belo Horizonte, Brazil, FPDS and trade staff worked together to increase the number of women working in the mining industry. Staff consulted with Canadian and Brazilian communities to advocate and adapt the Canadian “women in mining” approach for promotion and implementation in Brazil.

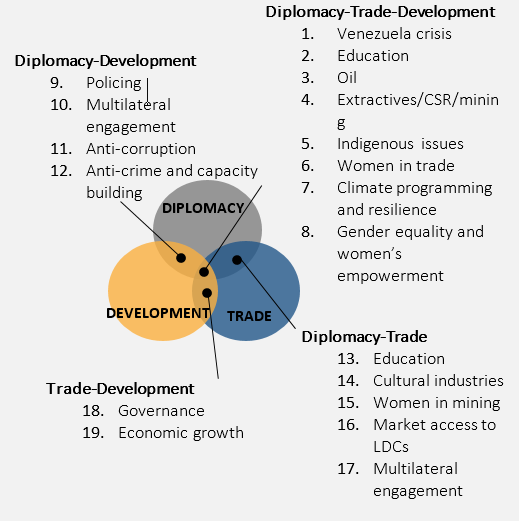

Thematic areas of leveraged expertise

During interviews, Branch staff at headquarters and across the region provided examples of leveraged expertise across business lines. The thematic area of each reference, or “mention,” as well as the coherence area in which it took place, were analyzed.

Figure 9. Mapping of thematic areas of mentions for cross-stream expertise, broken down by coherence area

A total of 19 thematic areas were identified where cross-stream expertise was leveraged, 42% of which took place in the diplomacy-trade-development coherence area. Education was identified in the diplomacy-trade-development area where development programs were present, and otherwise in the diplomacy-trade area.

Coherent programming and results

Diplomacy – Development

- Anti-corruption: Senior management staff at the Permanent Mission of Canada to the Organization of American States (OAS) noted a Honduras project where there was close collaboration between FPDS and development staff to deliver an anti-corruption initiative. Staff from working level to management viewed the OAS Mission to Support the Fight Against Corruption and Impunity in Honduras (MACCIH) as an initiative requiring the work of both business lines. Staff leveraged cross-stream expertise to advance the project and manage it in a way that aligned with both diplomacy and development objectives.

- Policing: Policing efforts in Haiti benefited from well-coordinated efforts across diplomacy, development and consular business lines. Programming in these areas required liaising with high-level officials in the Haitian government, and staff at the Embassy of Canada to Haiti collaborated closely and throughout their programming to coordinate their efforts.

- Anti-crime and capacity building: Staff at the Embassy of Canada to Guatemala leveraged expertise from diplomacy and development in their programming on anti-crime and capacity building. Because the work involved different implementing partners, FPDS and development staff integrated their internal and external meetings to ensure coordinated management of the projects and coherent messaging to external stakeholders.

Trade – Development

- Programming in Peru: Trade and development staff successfully leveraged cross-stream expertise for various aspects of Peru programming. A mutual focus on economic growth, in partnership with the local government, allowed for collaborative activities aiming to address economic stagnation. Work on governance through engagement with Pacific Alliance trading partners also leveraged expertise in the trade-development area.

These examples suggest that coherent programming is taking place in the LAC region, particularly in 19 thematic areas (see Figure 9). Nearly half of the documented examples of cross-stream collaboration took place in the diplomacy-trade-development area, while only 7% took place in the trade-development area.

However, while examples were documented for each coherence area, staff at the working level felt unable to leverage cross-stream expertise (see Figure 10), suggesting a difference in perspectives between senior management and working levels.

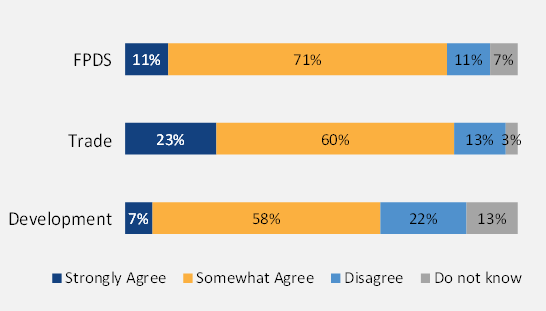

Survey results for leveraged expertise

Branch staff at headquarters and across the region were asked to rate their agreement with the following statement: “The different streams (FPDS, trade, international assistance) leverage expertise across business lines.”

Figure 10. Percent of survey respondents expressing their degree of agreement with the statement, broken down by business line

Text version

FPDS:

- Strongly agree: 11%

- Somewhat agree: 71%

- Disagree: 11%

- Do not know: 7%

Trade:

- Strongly agree: 23%

- Somewhat agree: 60%

- Disagree: 13%

- 3%: Do not know

Development:

- Strongly agree: 7%

- Somewhat agree: 58%

- Disagree: 22%

- Do not know: 13%

*The number of executive-level responses was too low to present a statistically significant breakdown between executive and non-executive responses. Executive perspectives were captured instead through key informant interviews.

Of all respondents, who were predominantly at the working level,* 13.8% of Branch staff strongly agreed, 62.6% somewhat agreed, and 16.2% disagreed with the statement. Another 7.3% did not know. A breakdown by business line indicates that trade staff most strongly agreed with, and development staff most strongly disagreed with, the statement.

Coherent programming and results

2. While the Branch was able to leverage expertise across business lines, missed opportunities for cross-stream collaboration were also identified

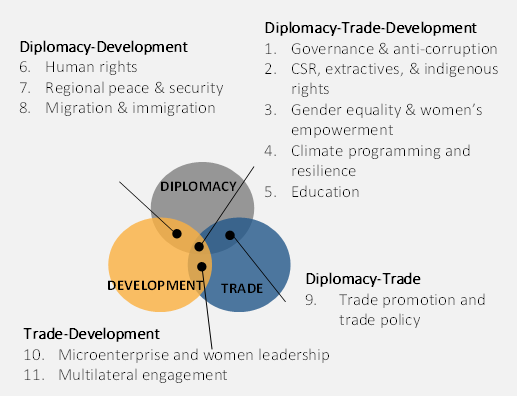

Although the Branch was able to leverage expertise across business lines in all coherence areas, cross-stream collaboration was largely driven either by external events or by individual initiatives. There were therefore missed opportunities for cross-stream collaboration. Eleven thematic areas emerged where the coherence of programming across business lines could be strengthened.

Eleven programming areas were identified where more consistent and formalized cross-stream collaboration could further strengthen linkages across business lines. These opportunities exist in all 4 coherence areas (see Figure 11). Examples include the following:

Governance and anti-corruption: Evolving economic and political situations were noted throughout the LAC region. Governance and anti-corruption efforts were identified as an area to strengthen linkages across diplomacy, trade and development. For example, a country in the LAC region decided to align more closely with the international community by strengthening its democracy, promoting rule of law and bolstering its economy. In the absence of a coordinated strategy, mission staff noted a missed opportunity in providing coherent support to the national government and mechanisms from across all 3 business lines to help with the democratic transition.

Trade promotion and trade policy: The potential for free trade agreement negotiations to benefit from trade promotional activities—particularly successes—was suggested. For example, FPDS staff in one country met with ministers from the education sector, and noted a lack of access to Canadian educational successes in the country, which could have been leveraged as part of the negotiations.

Microenterprise and women leadership: A mission in the LAC region identified an opportunity for a trade-development initiative to connect women entrepreneurs in the country with a Canadian company. Because the initiative was primarily between trade and development, the Canada Fund for Local Initiatives (CFLI) funding mechanism was viewed as inappropriate. Staff therefore applied for funding through the Business Women in International Trade (BWIT) program, but were unsuccessful in receiving funding. The application was rejected because the Canadian company was not staffed by women; the women entrepreneurs were from the LAC region. With no funding mechanism available, the initiative was not pursued.

Several factors limited the Branch from consistently leveraging expertise across business lines, including the lack of collaboration during planning cycles, limited mechanisms to learn from regional colleagues, and predominantly stream-specific meetings between Headquarters and missions.

Thematic areas for cross-stream collaboration opportunities

During interviews, Branch staff at headquarters and across the region provided examples of cross-stream collaboration opportunities. The thematic area of each reference, or “mention,” as well as the coherence area in which it took place, were analyzed.

Figure 11. Mapping of interview mentions of cross-stream collaboration opportunities, broken down by coherence area

A total of 11 thematic areas were identified where cross-stream expertise could be better leveraged.

Coherent programming and results

3. There was evidence that Canada’s presence in the region lacked a unified voice with external interlocutors, pointing to a need for strengthened coherence across business lines

In the theory of change that determined the expected benefits of coherent programming across diplomacy, trade and development, a unified voice with external interlocutors was determined as an expected outcome of coherence. The Branch was therefore assessed for a unified voice across business lines with external partners and stakeholders. Overall, there was evidence that Canada’s presence in the region lacked a unified voice, pointing to a need for strengthened coherence across business lines.

Previous evaluations have identified the importance of unified external communication messaging for Canada. Out of 20 evaluations conducted by GAC with coherence recommendations or findings between 2015 and 2019, 4 cited the need for a unified vision and voice for Canada’s bilateral relationships to ensure coherent external messaging. These evaluations extend beyond the LAC region but include the recent evaluations of Peru and Colombia country-program development programming, both of which highlighted the lack of a unified voice with external interlocutors.

“Challenges in communicating a coherent “Canada message” made it difficult for external stakeholders to obtain a clear picture of Canada’s overall engagement in Colombia.”

“There was no strategy for Canadian cooperation partners to share information and engage in common messaging to advance key priorities.”

Interview analysis indicated consensus among Branch staff that the role of the head of mission (HOM) is to represent Canada’s interests in the country of accreditation. However, there were mixed views about a unified voice for Canada at the country level, with polarizing views within and across business lines (see Figure 12). Notably:

HOMs expressed frustration with competing messages communicated to key interlocutors by different business lines. In one mission, for example, program heads met separately with the same stakeholder for similar purposes within days of each other, with neither program head having knowledge of the other meeting. The HOMs noted that their role as head of mission was to be the “face and voice” of Canada in their countries of accreditation, but that their ability to play this role was hindered by a lack of coordination.

Good practices for unifying external messages were identified in the region. For example, in one mission, after a joint planning retreat that helped staff to note the activities and priorities of other business lines, staff began to share upcoming external meetings. The practice supported coordination with external stakeholders and also led to better cross-stream collaboration, where common interlocutors were identified.

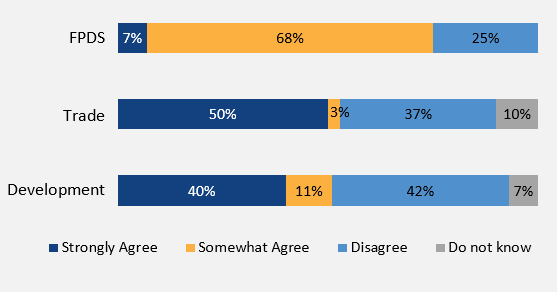

A unified voice with external interlocutors

Branch staff at headquarters and across the region were asked to rate their agreement with the following statement: “The different streams have a unified voice for our bilateral relationships in the LAC region.”

Figure 12. Percent of survey respondents expressing their degree of agreement with the statement, broken down by business line

Text version

FPDS:

- Strongly agree: 7%

- Somewhat agree: 68%

- Disagree: 25%

Trade:

- Strongly agree: 50%

- Somewhat agree: 3%

- Disagree: 37%

- Do not know: 10%

Development:

- Strongly agree: 40%

- Somewhat agree: 11%

- Disagree: 42%

- Do not know: 7%

Of all respondents, who were predominantly at the working level, 29.2% of Branch staff strongly agreed, 30.0% somewhat agreed, and 35.7% disagreed with the statement. Another 4.8% did not know. A breakdown by business line indicates that trade staff and development staff most strongly agreed with the statement, and also most strongly disagreed.

Organizational coherence: leadership

4. Cross-stream priorities were not clearly identified by Branch senior management, which may have led to an uncoordinated approach across business lines

Six organizational elements that enable coherence were identified by the first coherence evaluation, one of which was leadership. The Branch was therefore assessed on the degree to which senior management set a clear vision and priorities across business lines. It was difficult to conclude that clear cross-stream priorities were present, which may have led to an uncoordinated approach across business lines.

After reviewing over 50 policy and programming documents, the evaluation was unable to conclude that clear priorities were set by Branch senior management across business lines. Four documents included priorities for the LAC region: the 2018-19 Branch business plan, a LAC positioning paper describing the strategic priorities for the region, and 2 briefing documents citing the priorities in the region as advancing a progressive trade agenda that promotes gender equality, human rights, prosperity, resilience and democratic governance.

However, the planning commitments noted in the business plan were stream-specific, and opportunities for cross-stream collaboration were difficult to identify in the planned initiatives towards these commitments. The strategic priorities laid out in the LAC positioning paper crossed business lines, yet the linkages to the Branch business plan and subsequent cross-stream initiatives towards these priorities were challenging to identify.

A review of Strategia revealed 75 discrete priorities for 26 countries across the region, often siloed by business line (see Annex B). Seven broad cross-stream priorities were identified. When asked in a survey to rank the importance of these 7 priorities to their work, responses varied notably based on country-level context. Sub-regional trends were evident.

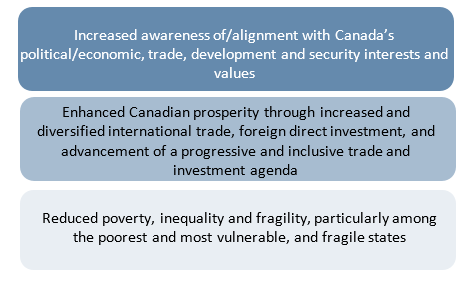

Figure 13. Branch priorities for the LAC region bureaus (2018-19 Branch business plan)

Figure 14. Branch priorities for the LAC region (2018-19 LAC positioning paper)

Figure 15. Branch mission priorities for the LAC region (2018-19 Strategia priorities)

Organizational coherence: leadership

The evaluation also identified the risks of an uncoordinated approach across business lines to achieve Branch priorities:

Potential to work at cross-purposes at the country level. During the time period covered by the evaluation, GAC considered simultaneously imposing sanctions on, signing a large commercial contract with, and providing development assistance to a country government in the region.

Potential for disharmonized priorities across business lines. Mission staff tried to implement a CSR initiative but had to grapple with the tension between the differing priorities across business lines related to commercial interests, protection of the most vulnerable, and issues related to anti-corruption and transparency.

Branch staff noted benefits of developing country-level strategies to ensure a coherent approach across business lines, sub-regional operational frameworks that allow staff to learn from experiences in countries working towards similar priorities, and a regional operational framework that helps to clarify the priorities of major importance to the department.

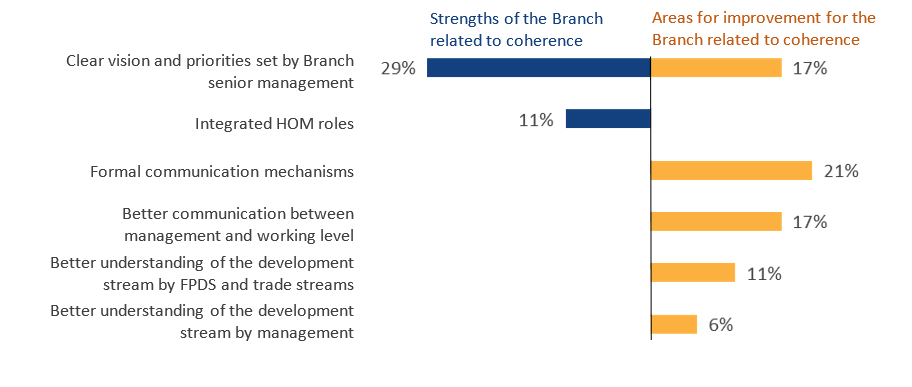

A survey of all Branch staff, for which responses were predominantly at the working level,* pointed to a potential disconnect between leadership and working levels in the Branch. In open-ended questions about the strengths and areas for improvement for coherence in the Branch, the following areas were identified (Figure 17). Interestingly, a clear vision and priorities from senior management were cited as both a strength and a weakness for the Branch.

*The number of executive-level responses was too low to present a statistically significant breakdown between executive and non-executive responses. Executive perspectives were captured instead through key informant interviews.

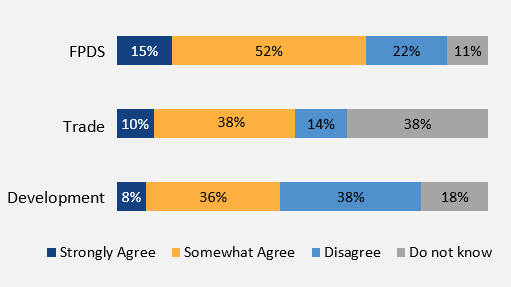

Branch leadership

Branch staff at headquarters and across the region were asked to rate their agreement with the following statement: “NGM senior management has articulated a clear vision and priorities across business lines.”

Figure 16. Percent of survey respondents expressing their degree of agreement with the statement, broken down by business line

Text version

FPDS:

- Strongly agree: 15%

- Somewhat agree: 52%

- Disagree: 22%

- Do not know: 11%

Trade:

- Strongly agree: 50%

- Somewhat agree: 3%

- Disagree: 37%

- Do not know: 10%

Development:

- Strongly agree: 40%

- Somewhat agree: 11%

- Disagree: 42%

- Do not know: 7%

Of all responses, which were predominantly at the working level, 13.1% of Branch staff strongly agreed, 39.4% somewhat agreed and 27.2% disagreed with the statement. Another 20.2% did not know. A breakdown by business line indicates that FPDS staff most strongly agreed with, and development staff most strongly disagreed with, the statement.

Figure 17: Proportion of themes in open-ended questions of online survey, broken down by strengths and areas of improvement identified for the Branch related to coherence

Text version

Clear vision and priorities set by Branch senior management:

- Strengths of the Branch related to coherence: 29%

- Areas for improvement for the Branch related to coherence: 17%

Integrated HOM roles:

- Strengths of the Branch related to coherence: 11%

- Areas for improvement for the Branch related to coherence: 0%

Formal communication mechanisms:

- Strengths of the Branch related to coherence: 0%

- Areas for improvement for the Branch related to coherence: 21%

Better communication between management and working level:

- Strengths of the Branch related to coherence: 0%

- Areas for improvement for the Branch related to coherence: 17%

Better understanding of the development stream by FPDS and trade streams:

- Strengths of the Branch related to coherence: 0%

- Areas for improvement for the Branch related to coherence: 11%

Better understanding of the development stream by management:

- Strengths of the Branch related to coherence: 0%

- Areas for improvement for the Branch related to coherence: 6%

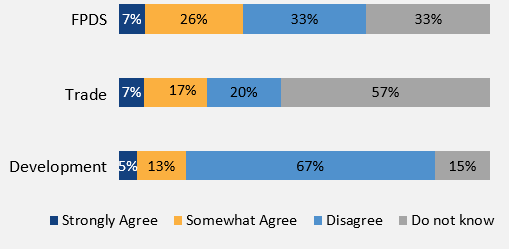

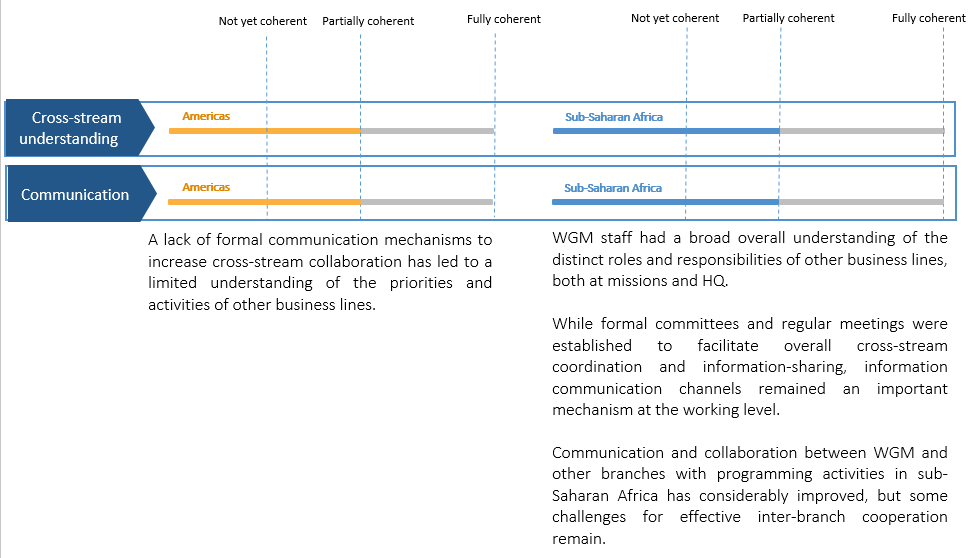

Organizational coherence: internal communication and cross-stream understanding

5. A lack of formal communication mechanisms to increase cross-stream collaboration has led to a limited understanding of the priorities and activities of other business lines

Of the 6 organizational elements that enable coherence identified by the first coherence evaluation, 2 were: 1) the presence of formal cross-stream communication mechanisms, and 2) the degree to which staff in each business line understood the priorities and activities of other business lines. The Branch was therefore assessed on both of these elements. Overall, a lack of formal communication mechanisms has led to a limited understanding of the priorities and activities of other business lines, suggesting this as an area where coherence could be strengthened.

The importance of formal cross-stream communication mechanisms was emphasized by representatives from like-minded countries who have made efforts toward coherence across diplomacy, trade and development. Publications from multilateral organizations also emphasize the value of these mechanisms, namely: 1) an increased understanding of other business lines, and their roles and responsibilities; 2) a driver for culture change, as staff in different business lines begin to better understand the work of their colleagues; and 3) a facilitator for leveraging expertise across business lines.

Branch staff indicated a lack of understanding of the priorities and activities of other business lines—particularly of how each stream contributes to the broader objectives of bilateral relationships. FPDS officers noted that other business lines often determine diplomatic priorities. Development officers expressed frustrations that diplomatic priorities sometimes drive the development agenda. Better understanding of roles and responsibilities, particularly of development work by other business lines, was noted as an area for improvement of coherence flagged in open-ended questions in the all-staff survey. Suggestions for strengthening cross-stream understanding included:

- cross-stream exposure, particularly through assignments or shared responsibility for files

- formal communication mechanisms, such as working groups or cross-stream meetings

Interviews provided examples of informal cross-stream communication in 5 countries: Colombia, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua and Peru. Staff expressed concerns about the longevity of informal communications as a means of sharing expertise, given the rotational aspect of the department. A lack of formal communication mechanisms was the most frequently cited area for improvement to strengthen coherence in the Branch. Staff also cited the need for better communication between management and working level, as well as between HQ and missions.

Yet, evidence shows that formal communication mechanisms alone may not be sufficient for coherent programming if staff do not also have access to funding mechanisms that allow them to implement cross-stream projects or initiatives. The only current source of funding for joint initiatives is the CFLI, which allows diplomatic staff to implement initiatives that are aligned with the Official Development Assistance Act. There is no similar funding mechanism for the trade-development area.

Formal communication

Branch staff at headquarters and across the region were asked to rate their agreement with the following statement: “Regular meetings and working groups are in place in NGM and are inclusive of staff from all business lines and levels.”

Figure 18. Percent of survey respondents expressing their degree of agreement with the statement, broken down by business line

Text version

FPDS:

- Strongly agree: 7%

- Somewhat agree: 26%

- Disagree: 33%

- Do not know: 33%

Trade:

- Strongly agree: 7%

- Somewhat agree: 17%

- Disagree: 20%

- Do not know: 57%

Development:

- Strongly agree: 5%

- Somewhat agree: 13%

- Disagree: 67%

- Do not know: 15%

Of all respondents, who were predominantly at the working level, only 6.9% of Branch staff strongly agreed with the statement, while 21.7% somewhat agreed and 42.6% disagreed with the statement. Another 28.7% did not know. A breakdown by business line indicates that development staff most strongly disagreed with the statement, while trade staff mostly did not know.

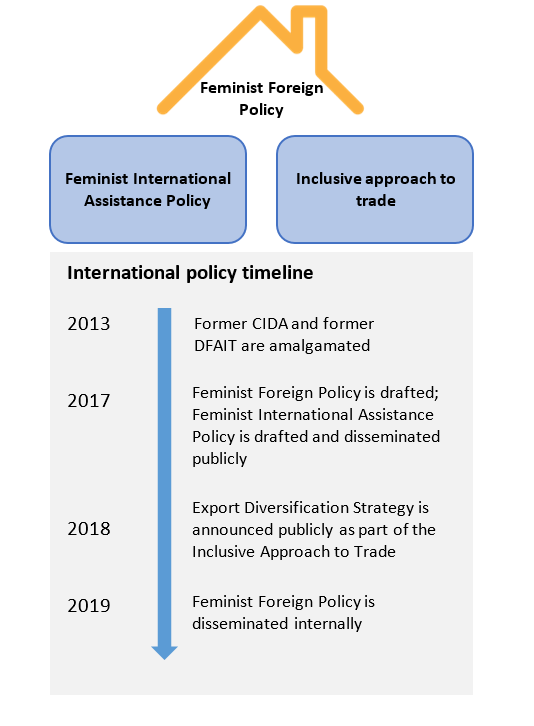

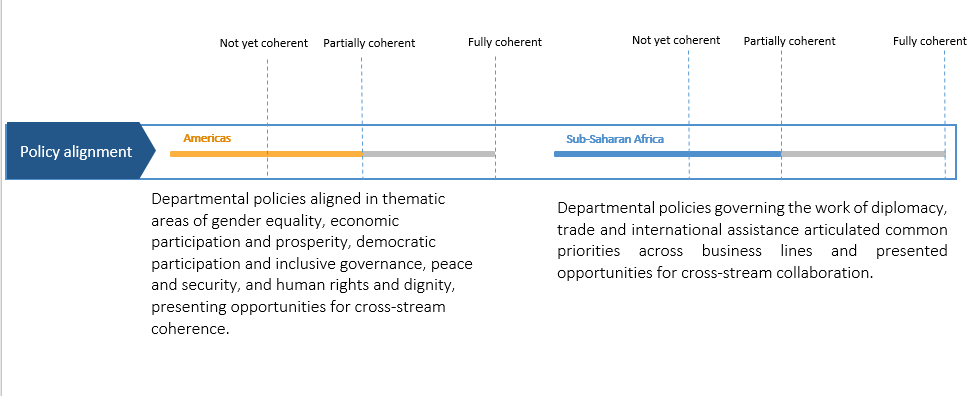

Organizational coherence: policy alignment

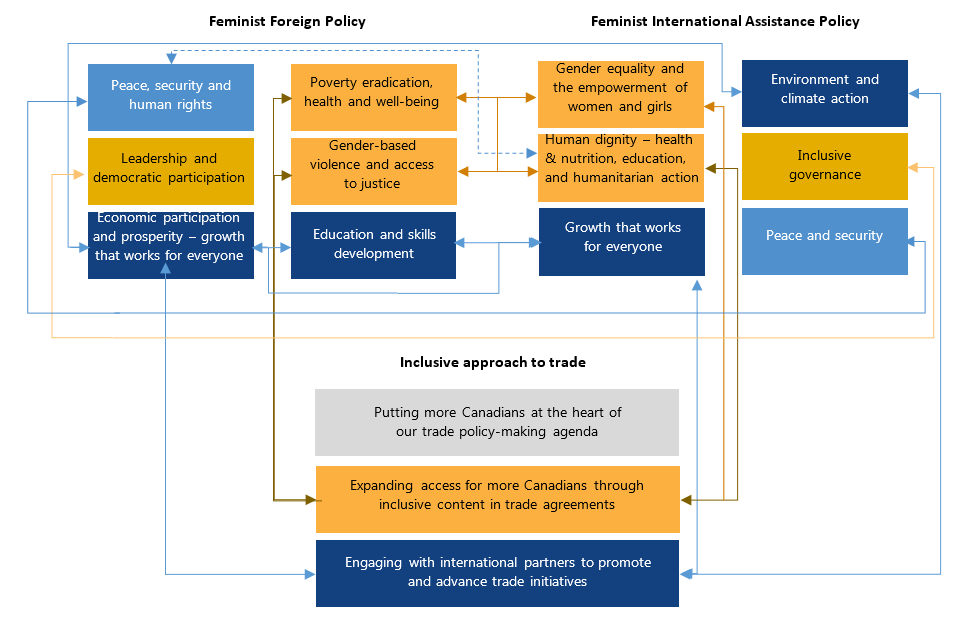

6. Departmental policies aligned in thematic areas of gender equality, economic participation and prosperity, democratic participation and inclusive governance, peace and security, and human rights and dignity, presenting opportunities for cross-stream coherence

Policy alignment was identified by the first coherence evaluation as one of 6 organizational elements that enable coherence. The extent to which departmental policies that govern diplomacy, trade and development align was therefore assessed, as was the potential impact of policy alignment on cross-stream coherence in the Branch. It was found that departmental policies aligned in thematic areas of gender equality, economic participation and prosperity, democratic participation and inclusive governance, peace and security, and human rights and dignity, presenting opportunities for cross-stream coherence. However, an inability to identify these cross-policy linkages may have presented challenges for the Branch in coordinating cross-stream collaboration.

In 2017-18, the department drafted a Feminist Foreign Policy, which was disseminated internally in 2019. In 2017, Canada’s Feminist International Assistance Policy was launched, guiding all of Canada’s international assistance. The policy is implemented through 6 interlinked action areas, and promotes gender equality and empowerment of women and girls as a core action area and cross-cutting theme. The department also developed Canada’s National Action Plan on Women, Peace and Security, which aligns directly with the Feminist Foreign Policy and Feminist International Assistance Policy. Finally, over the past few years, Canada’s inclusive approach to trade was further developed and, in 2018, the Export Diversification Strategy was announced, which reaffirmed the inclusive approach to trade and growth. This approach has 3 pillars.

Figure 19. Presentation and timeline of departmental policies that govern diplomacy, trade and development

The Feminist Foreign Policy was developed as a scaffolding for the international policies that govern the department. A timeline of events is presented below.

Text version

Feminist Foreign Policy

Feminist International Assistance Policy / Inclusive approach to trade

International policy timeline

2013:

- Former CIDA and former DFAIT are amalgamated

2017:

- Feminist Foreign Policy is drafted

- Feminist International Assistance Policy is drafted and disseminated publicly

2018:

- Export Diversification Strategy is announced publicly as part of the inclusive approach to trade

2019:

- Feminist Foreign Policy is disseminated internally

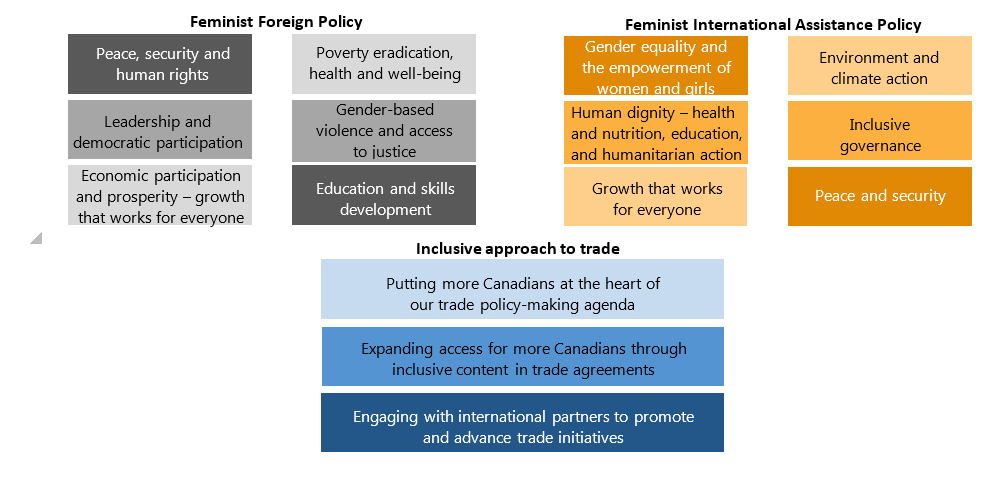

Figure 20. Thematic areas of departmental international policies

Text version

Thematic areas of departmental international policies

Feminist Foreign Policy:

- Peace, security and human rights

- Poverty eradication, health and well-being

- Leadership and democratic participation

- Gender-based violence and access to justice

- Economic participation and prosperity – growth that works for everyone

- Education and skills development

Feminist International Assistance Policy

- Gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls

- Environment and climate action

- Human dignity – health and nutrition, education, and humanitarian action

- Inclusive governance

- Growth that works for everyone

- Peace and security

Inclusive approach to trade

- Putting more Canadians at the heart of our trade policy-making agenda

- Expanding access for more Canadians through inclusive content in trade agreements

- Engaging with international partners to promote and advance trade initiatives

Organizational coherence: policy alignment

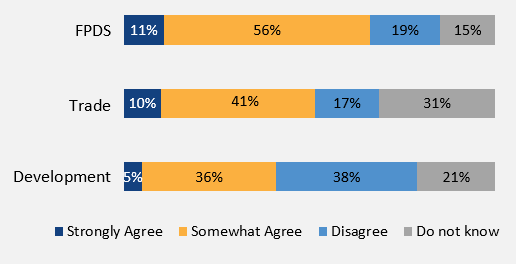

Policy alignment

Branch staff at headquarters and across the region were asked to rate their agreement with the following statement: “NGM has complete alignment of departmental policies across business lines.”

Figure 21. Percent of survey respondents expressing their degree of agreement with the statement, broken down by business line

Text version

FPDS:

- Strongly agree: 11%

- Somewhat agree: 56%

- Disagree: 19%

- Do not know: 15%

Trade:

- Strongly agree: 10%

- Somewhat agree: 41%

- Disagree: 17%

- Do not know: 31%

Development:

- Strongly agree: 5%

- Somewhat agree: 36%

- Disagree: 38%

- Do not know: 21%

Of all respondents, who were predominantly at the working level, only 9.6% of Branch staff strongly agreed with the statement, while 42.9% somewhat agreed and 27.2% disagreed with the statement. Another 20.2% did not know. A breakdown by business line indicates that development staff most strongly disagreed with the statement.

The Feminist Foreign Policy, the “chapeau” for international policies in the department, provides a framework for policy coherence across the international policies for each stream. Several cross-policy thematic areas were evident, including gender equality, economic participation and prosperity, democratic participation and inclusive governance, peace and security, and human rights and dignity.

Figure 22. Mapping of thematic alignment across Feminist Foreign Policy, Feminist International Assistance Policy, and inclusive approach to trade

While policy alignment was present in multiple thematic areas (see Figure 22), linkages across international policies were not well understood by the Branch. This presented challenges in coordinating across business lines to ensure that cross-stream initiatives materialized in the field. In a survey of all staff, only a small proportion (9.6%) agreed that departmental policies aligned across business lines (see Figure 21). This may be partly because the linkages were not clearly articulated by the policies, making it difficult to identify them and resulting cross-stream opportunities.

Canada’s foreign, trade and development policies were compared to those of 10 like-minded countries. Both Sweden and the Netherlands have a unified policy across diplomacy, trade and development cooperation. All other countries showed evidence of distinct but linked international policies: France, Germany, New Zealand, Norway, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States. For specific evidence for each country, please see Annex C.

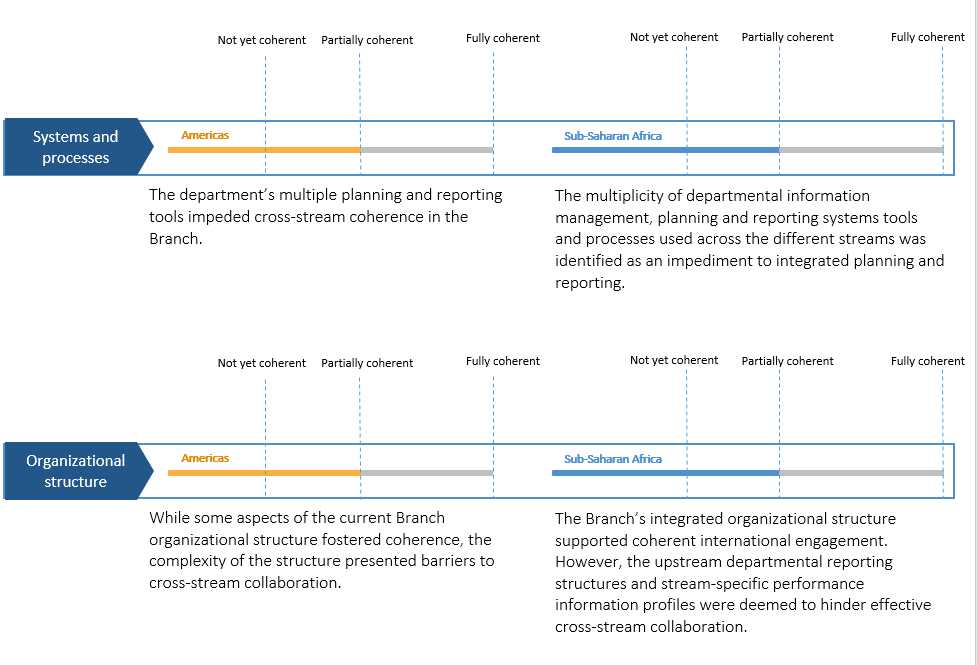

Organizational coherence: systems and processes

7. The multiple planning and reporting tools in the department impeded cross-stream coherence in the Branch

Systems and processes were identified by the first coherence evaluation as one of 6 organizational elements that enable coherence. The congruence of departmental planning, monitoring and reporting tools across diplomacy, trade and development was therefore assessed, as were the potential impact on cross-stream coherence in the Branch. It was found that the multiple planning and reporting tools in the department impeded cross-stream coherence in the Branch.

The following challenges stemming from incongruent systems and processes were identified:

Branch staff noted the use of Strategia, TRIO2, MSR+ reports, MyInternational, SAP, MRT and COSMOS by various business lines for various purposes. Staff perceived these various reporting tools as creating silos and impeding the ability to capture results from cross-stream efforts. The potential for Strategia to bring business lines together and encourage cross-stream linkages was noted.

Each business line engaged in a different planning cycle, with varied timing, requirements and systems for diplomacy, trade and development. These variations posed a significant challenge to joint and integrated planning across business lines, disincentivizing collaboration.

Staff also indicated the impact of onerous approval processes on meaningful joint planning. Interviewees noted the challenge in identifying the appropriate point in the planning cycle to engage across streams, given the lengthy approval timelines.

An evaluation of geographic coordination and mission support across the whole department, completed in January 2020, identified the following:

- the department employs a minimum of 8 corporate planning and reporting tools, each with disparate primary users

- there is poor interoperability between systems, including the inability to link or import data from one system to another

- the department’s multiple planning and reporting tools undermine the effective use of Strategia, intended as an integrated planning, monitoring and reporting tool across business lines

- Strategia does not support project-level planning and reporting, and timelines do not correspond with the international assistance programming management cycle

The evaluation recommended that the bureau responsible for Strategia collaborate with other relevant departmental stakeholders to develop an approach to strengthen the department’s planning, monitoring and reporting tools.

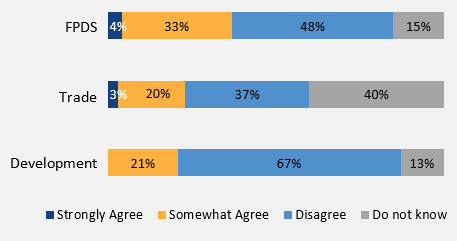

Systems and processes

Branch staff at headquarters and across the region were asked to rate their agreement with the following statement: “Departmental systems and processes are consistent and compatible, allowing for a complete understanding of outcomes and synergies across business lines.”

Figure 23. Percent of survey respondents expressing their degree of agreement with the statement, broken down by business line

Text version

FPDS:

- Strongly agree: 4%

- Somewhat agree: 33%

- Disagree: 48%

- Do not know: 15%

Trade:

- Strongly agree: 3%

- Somewhat agree: 20%

- Disagree: 37%

- Do not know: 40%

Development:

- Strongly agree: 0%

- Somewhat agree: 21%

- Disagree: 67%

- Do not know: 13%

Of all respondents, who were predominantly at the working level, only 4.3% of Branch staff strongly agreed with the statement, while 25.2% somewhat agreed and 51.3% disagreed with the statement. Another 19.1% did not know. A breakdown by business line indicates that development staff most strongly disagreed with the statement, while trade staff mostly did not know. No development staff strongly agreed.

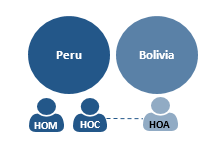

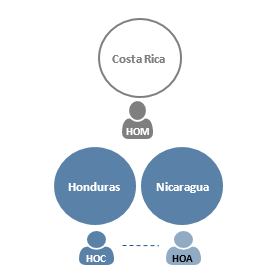

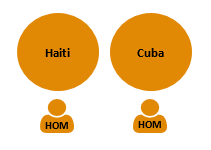

Delivery models to strengthen coherence

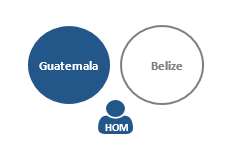

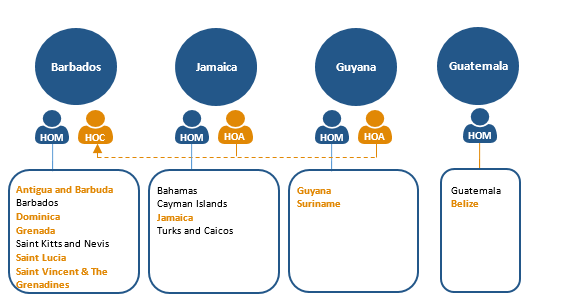

8. While some aspects of the current Branch organizational structure fostered coherence, the complexity of the structure presented barriers to cross-stream collaboration

As part of the organizational structure element identified by the first coherence evaluation as an enabler of coherence, the varied program delivery models used in the Americas Branch were assessed for their impact on coherence. Several program delivery models were identified in the organizational structure at Headquarters and missions. Overall, while some aspects of these models fostered coherence, their complexity impeded cross-stream collaboration, suggesting this as an area where cross-stream coherence can be strengthened in the Branch.

Both at Headquarters and in the mission network for the LAC region, some aspects of the organizational structure of the Branch fostered coherence. Most notably:

- a clear integration role was recognized for HOMs across the 3 business lines

- directors general were playing a similar integration role at Headquarters

However, the evaluation also noted several barriers to coherence resulting from the complexity of the organizational structure:

At headquarters, the majority of development support to missions was delivered by a separate division, the Strategic Planning, Policy and Operations division. Staff expressed interest in better integrating development across the 2 LAC bureaus (NLD and NDD).

At some missions, the complexity of hub-and-spoke models impeded cross-stream collaboration, particularly for countries with bilateral and regional development programs (see Annex D). These models also impeded the ability of HOMs to play their cross-stream integration role.

Coherence was promoted through cross-stream approval mechanisms in a small number of instances, which were reported to overcome the complexities of the overall structure.

Additionally, the organizational structure illustrated a range of possibilities—cross-stream integration at both Headquarters and in missions could take place at the officer level, or at the level of the ADM/HOM, or at any level in between. In considering the optimal point of integration, the evaluation noted concerns with the potential loss of specialized expertise and experience if integration took place too low in the hierarchy, thereby diluting specialized knowledge. Staff noted that the ideal configuration would balance the potential to build the depth and expertise of each business line, with the need to integrate teams to promote coherence.

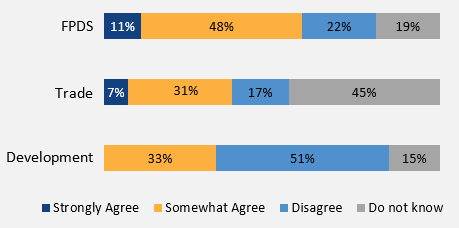

Organizational structure

Branch staff at headquarters and across the region were asked to rate their agreement with the following statement: “The organizational structure of NGM fully supports coherence across business lines.”

Figure 24. Percent of survey respondents expressing their degree of agreement with the statement, broken down by business line

Text version

FPDS:

- Strongly agree: 11%

- Somewhat agree: 48%

- Disagree: 22%

- Do not know: 19%

Trade:

- Strongly agree: 7%

- Somewhat agree: 31%

- Disagree: 17%

- Do not know: 45%

Development:

- Strongly agree: 0%

- Somewhat agree: 33%

- Disagree: 51%

- Do not know: 15%

Of all respondents, who were predominantly at the working level, only 6.1% of Branch staff strongly agreed with the statement, while 39.4% somewhat agreed and 32.4% disagreed with the statement. Another 21.9% did not know. A breakdown by business line indicates that trade staff mostly did not know while development staff most strongly disagreed with the statement, with no development staff responses indicating strong agreement.

Good practices for coherence

The Branch featured many encouraging examples of cross-stream coherence. Like-minded countries also shared good practices from their own experiences in promoting coherence across diplomacy, trade and development. The most promising examples, and those with the greatest potential for promoting Branch coherence, focused on cross-stream communication and opportunities. These examples are presented below.

Formal communication mechanisms as drivers for culture change

Representatives from a like-minded country observed that soon after their merger of diplomacy, trade and development into one department, formal communication mechanisms were put in place. These mechanisms were met with deep frustration from staff, who found them overly bureaucratic, of little value due to the vastly differing priorities across business lines, and unproductive because of the organizational culture. Over time, however, these formal communication mechanisms were credited for driving cultural change. They allowed business lines to better understand the work of colleagues and to slowly see their priorities as more similar than disparate.

Cross-stream exposure from shared responsibilities for files

Two business lines in a mission in the LAC region were required to share responsibility for a file for 18 months, followed by a year of each business line leading the file. Despite challenges stemming from co-management, within 3 years both business lines better understood each other’s roles and responsibilities, and the file has been welcomed as a joint responsibility since.

Joint planning retreats

Joint planning retreats were a noted good practice where mission staff across business lines brainstormed collaboratively on the objectives and priority areas for the upcoming year. Staff found it easier to understand the work of their colleagues, identify areas of their work that might be of interest to their colleagues, and more naturally work across business lines as a result of genuine joint planning.

Joint planning was also noted to lead to better meeting coordination across business lines, where staff began to share upcoming external meetings. The practice ensured coordination with external partners and stakeholders, and also led to better cross-stream collaboration where common interlocutors were identified.

Cross-stream opportunities: The trade-development area

In 2020, GAC evaluated the International Business Development Strategy for Clean Technology. The evaluation found that cross-stream opportunities between trade and development could allow for better collaboration across business lines on climate finance, to deliver on objectives of the Paris Agreement as well as the Export Diversification Strategy. Targeting programming mechanisms for this coherence area could present an emerging practice for coherence, particularly as the least-tapped coherence area in the LAC region.

Conclusions

Overall, the Americas Branch has been able to leverage cross-stream expertise and promote coherence in a number of areas. There remain, however, further opportunities to better strengthen cross-stream coherence in the LAC region. See Annex E for scorecards for coherence, and Annex F for a comparison of findings between this and the first evaluation of coherence in sub-Saharan Africa.

What works well

- The Branch has leveraged expertise across business lines in all coherence areas, with concrete examples in all 3 sub-regions, in several thematic areas, and in both big and small missions.

- Departmental international policies that govern diplomacy, trade and development aligned in thematic areas of gender equality, economic participation and prosperity, democratic participation and inclusive governance, peace and security, and human rights and dignity, presenting opportunities for cross-stream coherence.

- The organizational structure of the Branch includes some elements that foster coherence, and subsequent changes to the structure should retain these elements.

What needs further consideration

- There were missed cross-stream opportunities in all coherence areas. Missed opportunities in the trade-development area may have been impacted by the lack of funding mechanisms for trade-development initiatives that do not qualify for CFLI funding.

- A unified Canadian voice with external interlocutors was absent in the LAC region.

- Branch communication mechanisms were either informal or siloed by business lines.

- Branch cross-stream priorities were difficult to identify.

- Policy linkages were quite complex and therefore difficult to identify, presenting a barrier for the Branch in ensuring cross-stream activities.

- The siloed systems and processes in the department presented structural barriers to branches attempting to strengthen coherence.

Where action is required

- Develop a strategic framework. If coherence is a priority for the Branch, a strategic framework is needed for how the business lines will work together toward cross-stream priorities. Promoting coherence does not require all 3 business lines to implement programming in all countries and sub-regions—programming can be tailored to the local context yet still ensure that a unified and coordinated approach is taken.

- Implement formal cross-stream communication mechanisms, which have been noted to drive culture change, enable staff to leverage the expertise of their colleagues, and unify the voice for Canada with interlocutors.

- Revise the complex organizational structure to promote cross-stream coherence. At headquarters, development staff could be integrated so that all 3 business lines work closely together. This integration can lead to better cross-stream understanding and allow staff to identify opportunities for cross-stream collaboration. Additionally, the current hub-and-spoke models in the region could be reorganized to better reflect common priorities.

Recommendations and considerations

Recommendations

Based on the findings of this evaluation, the following actions are recommended for the Americas Branch:

- Improve the Branch strategic planning process across diplomacy, trade and development. The following actions could be considered:

- explicitly identifying cross-stream priorities for the region and sub-regions

- streamlining the list of priorities for the region and sub-regions

- conducting a joint planning exercise that involves all business lines

Findings 1, 2, 3, 4

- Implement formal cross-stream communication mechanisms to increase understanding of the roles and responsibilities across business lines and to leverage diplomacy, trade and development expertise. Formal mechanisms could include:

- cross-stream assignments or sharing responsibility for files

- working groups and/or regular meetings where common stakeholders are implicated

- joint strategic planning exercises

Findings 1, 2, 5, 6, 7

- Review the current organizational structure to streamline the complexity that impedes coherence of diplomacy, trade and development and implement models that promote cross-stream coherence. A review of the structure could consider:

- integration of development staff into Headquarter divisions and bureaus

- restructured hub-and-spoke models in the region to better reflect common priorities

Findings 2, 8, 9, 10

Considerations

Based on the findings of this evaluation, the following department-wide considerations for corporate guidance, horizontal learning and future programming have been identified.

Corporate guidance

Policy direction for coherence

Departmental policies align in several thematic areas, presenting opportunities for cross-stream coherence. Explicit references to linkages across international policies that govern diplomacy, trade and development could further promote coherent cross-stream programming across the department.

Rotation and mobility of staff

Incompatible departmental systems for information management, planning and reporting across business lines can create silos, disincentivize collaboration, and impact the ability to capture results on joint efforts. Department-wide efforts toward harmonizing and streamlining planning and reporting processes across business lines are needed.

Approval processes

Organizational structures play a key role in fostering of coherence across business lines. However, the siloing that remains at the departmental level presents a challenge for effective collaboration across streams at the branch level.

Departmental structure

Lengthy project approval processes and short turnaround times for input have an impact on the ability of business lines to engage in meaningful consultations, joint planning and the identification of opportunities for collaboration. Branches across the department need to take into consideration the time required to allow for coherent engagement.

Systems, tools, processes

While rotation and mobility of staff can promote the sharing of best practices and learning across business lines, it can also have a negative effect on corporate memory and coherence given the high turnover of staff.

Horizontal learning

Cross-stream opportunities

Opportunities for cross-stream temporary assignments and postings promote greater awareness and deeper appreciation for collaboration across business lines. Stream-specific expertise, skills and knowledge can inspire innovation and collaboration in other areas. Professional development and learning opportunities across business lines were deemed important for cross-stream collaboration.

Collaboration in coherence areas

The complexity of promoting coherence means that it will not develop organically. Coherent programming across the department requires a systematic and comprehensive approach. Concerted efforts could be placed on files in coherence areas to ensure coordination while leveraging the expertise of business lines.

Future programming

Flexibility of programming

Flexible program boundaries are needed to allow staff to leverage expertise across business lines. Availability of cross-stream programming mechanisms, particularly for the trade-development area, can ensure that opportunities can be realized.

Annexes

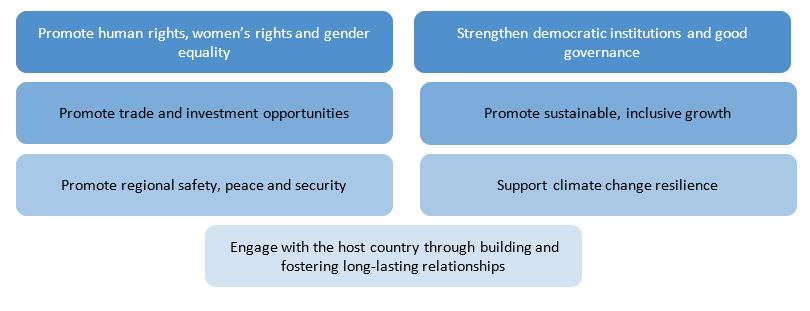

Annex A: Theory of change

*The evaluation faced challenges in identifying common language across business lines for desired changes in the region. While imperfect, the language ultimately agreed upon, “alignment with Canadian priorities,” felt relevant to all 3 business lines—and does not advocate for imposing Canadian values and norms in the LAC region.

This theory of change was developed in close collaboration with the Americas Branch, and was validated with the Performance Advisory Committee (PAC), a group of departmental experts on performance and results.

Annex B: Methodology for developing broad Strategia priorities

To better understand the country-specific priorities and conduct analysis on their similarities and differences, the evaluation team reviewed all priorities inputted into Strategia. The review comprised priorities for 26 countries across the region.

Analysis of these priorities was impeded by several factors. First, there was a noted lack of consistency in the development of priorities. Some priorities were concise, such as “governance,” whereas in other cases priorities were all-encompassing, for example “promote accountable and inclusive governance, diversity and pluralism in society, economic growth, gender equality, climate change, regional safety and security and multilateral cooperation.” Second, some priorities were so broad that all other priorities could be nested within it. Examples include priorities that have broad application, such as “advance our foreign policy agenda” or “promote shared values.” Finally, in a few instances, priorities were so specific to the local country or context that grouping could not be achieved. This occurred for 10 listed priorities.

The evaluation team developed the following methodology to mitigate these factors and develop 7 broad priorities that encompassed the majority of priorities listed in Strategia (59 of a total 75 priorities).

To improve consistency in listed priorities:

- All priorities were documented by sub-region

- Discrete priorities formed the basis of a list

- Each all-encompassing priority was tagged to the concise priorities referenced within it

For example, the priority “promote accountable and inclusive governance, diversity and pluralism in society, economic growth, gender equality, climate change, regional safety and security and multilateral cooperation” was tagged under the following discrete listed priorities:

- strengthen democratic institutions and good governance

- promote human rights, indigenous rights, LGBTQ+ rights, women’s rights and gender equality

- promote sustainable and inclusive growth

- support climate change initiatives

- promote regional safety, peace and security

To mitigate overly broad listed priorities:

- Where priorities were so broad that all other listed priorities could be nested within them, they were omitted from the list

- A total of 6 priorities were omitted using this criterion

To mitigate overly specific listed priorities:

- Where priorities were so specific that no grouping was possible, a frequency criterion was applied. Priorities that were listed 3 times or fewer were omitted from the list

- A total of 10 priorities were omitted using this criterion

The following 7 broad priorities were therefore developed from 59 priorities that met the criteria, with the following frequencies:

| Priority | % of times listed (total of 59) |

|---|---|

| 1. Promote human rights, women’s rights and gender equality | 34% (n=20) |

| 2. Strengthen democratic institutions and good governance | 32% (n=19) |

| 3. Promote trade and investment opportunities | 25% (n=19) |

| 4. Promote sustainable, inclusive growth | 19% (n=11) |

| 5. Promote regional safety, peace and security | 17% (n=10) |

| 6. Support climate change resilience | 14% (n=8) |

| 7. Engage with the host country through building and fostering long-lasting relationships | 8% (n=5) |

Annex C: Examples of intersecting international policies from like-minded countries

| Summary | Policy and related documents reviewed | |

|---|---|---|

| Australia | The 2017 Foreign Policy White Paper provides 5 key objectives for Australian diplomacy. Website pages related to trade and development explicitly reference alignment of activities and strategies with the White Paper. No other cross-references were identified (i.e. economic and cultural diplomacy did not refer to development efforts). |

|

| France | No overarching policy document for diplomacy, trade and development was found. Efforts at coherence focus on the SDGs and the Paris Agreement, as noted in the development policy aligns with the SDGs and trade approach. The objectives of France’s development policy were defined in a law passed in 2014 and reaffirmed in 2018. An example of coherence efforts is the “3D” approach in the Sahel, developed jointly by defence, diplomacy and development stakeholders. |

|

| Netherlands* | Policy documents reviewed make reference to each other and the need for policy coherence and deployment of all available instruments. Dutch development and trade policy coherence efforts are driven by the SDGs. Of note, the Dutch International Integrated Security Strategy notes that coordination efforts build on the integrated 3D approach of defence, diplomacy and development. |

|

| New Zealand | The Strategic Intentions 2019-23 identifies a framework that sets out impact over a 10-year horizon and includes 10 strategic goals. While there is no explicit reference to relevant policy documents, there are priorities and objectives that reflect efforts at coherence. For example: trade policy principles include inclusive growth, gender equity and environmental issues; the policy on International Cooperation for Effective Sustainable Development notes that in addition to aid, New Zealand will work to advance sustainable development through trade, environmental, diplomatic and security cooperation as an integrated approach to foreign policy. |

|