Evaluation of International Assistance Programming in Ethiopia 2013-14 to 2019-20

Evaluation Report

Prepared by the International Assistance Evaluation Division (PRA)

Global Affairs Canada

January 2021

Acronyms and Abbreviations

- AGP

- Agricultural Growth Program

- CEFM

- Child and Early Forced Marriage

- CFLI

- Canadian Fund for Local Initiatives

- CSO

- Civil Society Organization

- DAG

- Development Assistance Group

- DGGE

- Donor Group on Gender Equality

- DPD

- International Assistance Bureau

- ExCom

- Executive Committee of the Development Assistance Group

- FGM

- Female Genital Mutilation

- FIAP

- Feminist International Assistance Policy

- GAC

- Global Affairs Canada

- GE

- Gender Equality

- GSWG

- Gender Sector Working Group

- GDP

- Gross Domestic Product

- GNI

- Gross national income

- GoE

- Government of Ethiopia

- GTP

- Growth and Transformation Plan

- IDRC

- International Development Research Centre

- IFM

- International Security and Political Affairs

- HDI

- Human Development Index

- IHA

- International Humanitarian Assistance

- KFM

- Partnerships for Development Innovation Branch

- MFM

- Global Issues and Development Branch

- MNCH

- Maternal, Newborn and Child Health

- MHD

- International Humanitarian Assistance Bureau

- NDPPC

- National Disaster Prevention and Preparedness Committee

- ODA

- Official development assistance

- PSNP

- Productive Safety Net Program

- PSOPs

- Peace and Stabilization Operations Program

- RLLP

- Resilient Landscapes and Livelihoods for Women project

- SGBV

- Sexual and Gender Based Violence

- SGD

- Grants and Contributions Management

- SLMP

- Sustainable Land Management Program

- SNNP

- Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples Region

- SRHR

- Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights

- UNECA

- United Nations Economic Commission for Africa

- UNOCHA

- United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs

- WASH

- Water, Sanitation and Hygiene

- WEF

- Ethiopia Development Division

- WFC

- Pan-Africa and Regional Development Division

- WGM

- Sub-Saharan Africa Branch

- WVL

- Women’s Voice and Leadership

Executive Summary

This evaluation examined Canada’s international assistance programming in Ethiopia from 2013-14 to 2019-20. Due to the timing of data collection, it did not consider the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic or the internal conflict taking place in Tigray in late 2020. The objective was to inform decision-making and support policy and program improvements. This report presents the evaluation findings, conclusions and recommendations, as well as considerations to foster horizontal learning.

During the evaluation period, Ethiopia was the largest recipient of Canada’s international assistance in Africa. Canada’s support was strongly aligned with the Government of Ethiopia’s priorities, and closely tied to supporting its flagship programs for increased food security and agricultural growth, e.g. the PSNP and the AGP. Additional programming was to a large extent designed to complement these major contributions. This approach, guided by a multi-year country strategy and active participation in policy dialogue and donor coordination, helped establish Canada as a trusted partner in Ethiopia and maximized development programming coherence. Pre-feasibility studies are serving to provide an evidence base to inform future programming, in line with recent economic and political reforms in Ethiopia.

Additional programming in agriculture contributed to increased productivity and household incomes for smallholder farmers, and complementary interventions in nutrition, MNCH and WASH have contributed to improving the overall health of targeted women and children. Canada’s support of economic growth helped to generate new businesses, off-farm employment opportunities and access to finance, in particular for women and youth. Programming also featured many encouraging examples of using innovation. However, a strong focus on micro and small enterprises, combined with persistent challenges linked to the investment climate and market linkages in Ethiopia, limited the potential for large-scale results and income generation. There was also a limited inclusion of a climate change lens in programming, which showed a gap in alignment with current Ethiopian priorities and needs.

While Canada has been considered a strong voice on gender equality in Ethiopia for many years, the introduction of the FIAP saw a significant increase in specific gender equality programming and a realignment of ongoing projects to better focus on gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls. Early and promising results to support their SRHR and to address widespread use of CEFM, FGM and other SGBV are already emerging. This, however, has to be put in the context of the enormous barriers that persist for women’s social, economic and political inclusion and access to resources.

In a context that was highly volatile because of environmental and political crises, Canada offered a continuum of programming to address the needs of the most vulnerable, from emergency assistance, to social safety nets, to long-term development. By doing so, Canada contributed to building resilience in Ethiopia by strengthening vulnerable populations’ capacities to respond, adapt to and prepare for shocks. There were also some notable examples of project-level flexibility to respond to emerging crises, including working closely with trusted partners to reorient development projects towards meeting immediate humanitarian needs. However, there is a continued need to strengthen complementarity and coordination across international assistance streams, in particular linked to humanitarian and development assistance, while also considering the role Ethiopia plays in promoting security and stability in Eastern Africa.

Summary of recommendations

- WEF should develop a multi-year strategic plan in line with departmental guidance and explore how to find a balance between contributions to pooled funds, technical assistance and complementary programming in support of evolving Ethiopian priorities.

- WEF should explore opportunities to accompany Ethiopian efforts to build a green economy by replicating successful small-scale innovations and good practices within and between regions in Ethiopia.

- WEF should explore how to further strengthen its programming linked to the environment and climate action to better reflect Ethiopia’s vulnerability to climate change, especially in the agricultural sector.

- WEF should explore how to better integrate conflict analysis and a humanitarian, development and peace nexus perspective into programming and how it can contribute to on-going departmental efforts to apply a nexus approach in collaboration with MFM and IFM.

- WEF should document best practices and lessons on the use of mechanisms for project-level adaptability (pseudo-crisis modifiers) in recent programming in Ethiopia and share with SGD and DPD.

- SGD and DPD should develop guidance on how crisis modifiers or similar mechanisms could be applied in new or existing projects, when relevant and feasible.

Program Background

Ethiopia Country Context

Text version

Map of Ethiopia

Administrative Divisions in Ethiopia

Ethiopia is divided into 9 regions based upon ethnic groupings. There are also two chartered cities, Addis Ababa and Dire Dawa.

The country is then further divided into zones, woredas and kebeles. The kebele is the smallest administrative unit, similar to a ward or a neighbourhood.

Despite promising economic growth, widespread reforms and greater openness, poverty remains a development challenge.

Ethiopia has been the fastest growing economy in Africa over the past decade, averaging around 10% yearly GDP growth, prior to the COVID-19 crisis. Government investments in key areas have contributed to improvements in nutrition, maternal and child mortality, primary educational attainment, and other development indicators. The appointment of Abiy Ahmed as prime minister in 2018 also led to wide-ranging economic, social and political reforms. Agriculture remains as a key sector for Ethiopia’s strategy for a climate-resilient green economy, but a stronger focus is put on building a strong private sector tied to manufacturing, mining, tourism, communication and technology, as well as greater openness to foreign investments. Eased funding restrictions as a result of the 2019 CSO Proclamation have created improved conditions for advocacy and human rights-based approaches. These changes have elicited both optimism and resistance in a continued fragile context.

However, Ethiopia remains one of the poorest countries in the world, ranking 173 out of 189 countries according to the 2019 United Nations HDI. Over 70% of the population are currently under the age of 30, with many young people unable to find formal jobs in an underdeveloped private sector. Malnutrition and access to sanitation facilities are also notable challenges, especially for women and children. Gender inequalities still persist in economic participation, political empowerment, education and health, reflected in Ethiopia ranking 117 out of 149 countries in the World Economic Forum’s 2018 Global Gender Gap Report.

Reoccurring natural disasters, and continued political fragility and conflict.

With a population of over 100 million, rapid demographic growth is putting increasing pressure on land resources, expanding environmental degradation and raising vulnerability to food shortages. The majority of Ethiopians live in rural areas and engage in rain-fed subsistence agriculture, a sector heavily susceptible to climate change. In a typical year, approximately 8 million people are reliant on humanitarian assistance. The evaluation period also saw considerable political instability and civil unrest, culminating in two states of emergency in 2016-17 and 2018. Conflict, natural disasters and climate change forced many Ethiopians to flee their homes; in 2018 nearly 3.2 million people were internally displaced. As of May 2020, Ethiopia was hosting over 700,000 refugees and asylum seekers, mostly from the neighbouring countries of Somalia, Eritrea and South Sudan. As the host of the African Union and other international institutions, Ethiopia is seen as a key player in promoting security and stability in Eastern Africa. However, the country’s ability to effectively manage and address its own internal conflicts remains a challenge. Ethiopia is incredibly diverse in terms of geography, religion, language and ethnicity. The significant disparities between regions in terms of access to resources and political influence in its federal model based on ethnicity have led to violence, especially in regions that could potentially lose some of their previous political influence.

Program Background

Donor Relations

Canada was among the top ten donors in Ethiopia during this period, ranking 4th among bilateral donors. (Net ODA, 2013-18 total, millions of USD)

Text version

World Bank Group: $6,926

United States: $5,018

United Kingdom: $2,723

EU Institutions: $1,393

AfDB (African Development Bank): $1,249

Global Fund: $995

Germany: $657

GAVI: $595

Canada: $593

Netherlands: $493

Gates Foundation: $487

In 2018, Official Development Assistance (ODA) to Ethiopia totaled $4.93B, or 5.9% of gross national income (GNI). Ethiopia has attracted increasing amounts of ODA over this period, while ODA as a share of GNI has declined amidst rapid economic growth.

Bilateral Relations

Canada established diplomatic relations with Ethiopia in 1965. The embassy in Addis Ababa is responsible for relations with Ethiopia, as well as with Djibouti, the African Union and the UN Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA).

Ethiopia was consistently among Canada’s largest recipients of international assistance during the evaluation period. Efforts have been made to move beyond a traditional donor-recipient relationship. A number of recent official visits to Ethiopia have helped strengthen a political dialogue on shared priorities linked to gender equality, climate change, democracy and common regional security interests.

While two-way merchandise trade between Canada and Ethiopia has remained modest, totaling approximately $170 million in 2018, there have also been discussions between the two countries on how to expand commercial ties, in particular linked to mining, infrastructure, information and communications technology, agriculture and renewable energy. In June 2019, a bilateral MOU was signed that gives both countries an opportunity to collaborate in public-private partnerships on Ethiopian transportation, hydro and solar power projects.

Donor Coordination

Canada has been an active participant in many donor coordination platforms in Ethiopia. The overarching body is the Development Assistance Group (DAG) which brings together development partners working in the country. The members of the DAG Executive Committee (ExCom) rotate annually, and Canada has served on ExCom in 2013-14, 2014-15 and 2016-17. The DAG is structured around a biannual high level forum with the Ethiopian government and is organized according to government thematic priorities.

Within the DAG, Canada has participated in a number of sectoral working groups, such as those related to nutrition and food security, water and sanitation, health and population, and climate change. Canada also participated in the steering committees of Ethiopia’s flagship development programs, most notably the Productive Safety Net Program (PSNP). Canada co-chaired the DAG’s Donor Group on Gender Equality (DGGE) with UN Women from 2017 to August 2020, and the two have also been behind the creation of the DAG Gender Sector Working Group (GSWG), for which the Terms of Reference were endorsed in May 2019.

The Humanitarian Coordination Structure is governed through the National Disaster Prevention and Preparedness Committee (NDPPC). On the donor side, coordination efforts are led by the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) in conjunction with donors and other multilateral organizations. Canada’s Head of Cooperation participated in these humanitarian coordination bodies, as did representatives of the Ethiopia bilateral development program.

Program Background

Disbursements

Top Recipients of Canadian International Assistance, from 2013-14 to 2018-19 (GAC only, excludes contributions to multilateral institutions, millions of CAD)

Text version

Top Recipients of Canadian International Assistance, from 2013-14 to 2018-19 (GAC only, excludes contributions to multilateral institutions, millions of CAD)

Afghanistan: $1,084

Ethiopia: $703

Jordan: $665

Mali: $637

Syria: $626

WGM contributions towards GoE Flagship Programs

Text version

Other Bilateral: 54.9%

PSNP: 37.7%

AGP: 7.4%

RLLP: 0.5%

Global Affairs Canada Program Disbursements

During the evaluation period, Ethiopia was the largest recipient of Canada’s international assistance in Africa, and second in the world, with a total disbursement of $798.5M, corresponding to a yearly average of $114M (includes preliminary numbers for FY 2019-20). Disbursements were primarily done through three GAC program branches, e.g. WGM, MFM and KFM. Less than 1% of funds combined were disbursed through the International Security and Political Affairs Branch (IFM) and the Canada Fund for Local Initiatives (CFLI).

Text version

WGM: $523M

MFM: $207M

KFM: $66M

Sub-Saharan Africa Branch (WGM)

Disbursements from the Ethiopia bilateral development program (WEF) averaged $74.7M per year during the period. Bilateral programming had a strong focus on food security and agriculture, as well as off-farm economic growth. Support for Ethiopia’s flagship programs, most notably the Productive Safety Net Program (PSNP) and the Agricultural Growth Program (AGP), which was done through pooled funding mechanisms and technical assistance, totalled $238M, equivalent to 45.6% of all bilateral spending. The Pan-Africa and Regional Development Division (WFC) has an important presence in Ethiopia, but its allocations to Ethiopia-specific programming are not reflected in the total amount of disbursements due to financial coding practices.

Global Issues and Development (MFM)

Disbursements from the Global Issues and Development Branch averaged $29.5M per year, of which $25M was dedicated to humanitarian assistance, the latter representing 22% of total disbursements to Ethiopia. With the 2015-16 El Niño drought, humanitarian assistance peaked at nearly $42M in relief. Support to refugees from South Sudan was also a major focus of humanitarian assistance. Non-humanitarian investments included programming in maternal, newborn and child health (MNCH), improved nutrition, and child protection.

Partnerships for Development Innovation (KFM)

Disbursements from the Partnerships for Development Innovation Branch averaged $9.4M per year over the evaluation period. This included several multi-country projects focused on MNCH, agriculture and volunteer sending programs. KFM also supported innovation programming in Ethiopia through Grand Challenges Canada and research through partnerships with the International Development Research Centre (IDRC).

Evaluation Scope and Methodology

Evaluation Scope and Objectives

Evaluation Scope

The evaluation covers the period from 2013-14 to 2019-20, with an emphasis on the most recent years. Financial information and program reporting for 2019-20 are based on available departmental data as of July 2020.

The evaluation includes all official development assistance (ODA) disbursed by Global Affairs Canada through international assistance programming to Ethiopia during the period.

The evaluation sample included all projects funded by the bilateral development division during this time period, as well as a purposeful sample of KFM and MFM projects related to the evaluation’s case studies on gender equality and resilience.

Due to the timing of the data collection, this report does not include analysis of the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic or the internal conflict taking place in Tigray in late 2020.

Evaluation Objectives

The overall objectives of the evaluation were to:

- Contribute to informed decision-making, support policy and program improvements and advance departmental horizontal learning.

- Provide a neutral assessment in a transparent, clear, useful manner by highlighting how departmental resources have been used to optimize results.

Evaluation Approach

The evaluation was conducted in-house by the International Assistance Evaluation Division (PRA), supported by two local evaluators during the data collection mission. In addition, the evaluation team engaged a Canadian gender expert to support its case study on gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls.

The evaluation design was based on numerous consultations with program stakeholders at HQ and in Ethiopia, adopting a utilization-focused approach. The evaluation also sought to identify innovative approaches, lessons learned and best practices to achieve results.

Grounded in the evaluation questions, the evaluation examined how a changing context impacted Canadian international assistance programming with a focus on adaptability, resilience, gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls.

Evaluation Questions

| Evaluation Issue | Questions |

|---|---|

| Adaptability Relevance Efficiency | Q1. To what extent did Canada’s international assistance adapt to changes in context, needs and priorities in Ethiopia, as well as to changing departmental priorities? Q2. What factors facilitated or limited the programming’s ability to adapt? |

| Results Effectiveness Gender Equality | Q3. What results (intended/unintended) have been achieved by Canadian international assistance in key programming areas? Q4. To what degree have processes and other measures to target and achieve results for women and girls been effective? |

| Resilience Contributions to Sustainability | Q5. Have Canadian international assistance programming and departmental approaches been complementary and added value to building resilience in Ethiopia? In what ways? |

Methodology

The evaluation used a mixed-methods approach, where data was collected from a range of sources to ensure multiple lines of evidence when analyzing data and formulating findings. While examples are used for illustrative purposes, each finding has been triangulated using evidence from a mix of quantitative and qualitative data. Seven main methods were applied to conduct this evaluation:

Document Review and Financial Analysis

Review of internal Global Affairs Canada documents:

- Policy documents

- Planning and strategy documents

- Annual reports

- Briefing notes and memos

- Evaluations, audits and reviews

- Review of statistical CFO data of total disbursements, delivery mechanisms, targeted thematic and action areas, OECD-DAC sectors, approval timelines, gender coding, and variations over time.

Literature Review

Review of academic literature, partner publications and other secondary documentation, including:

- A standalone review was conducted by a third party on food security and nutrition in Ethiopia

- Specialized studies on key development issues in Ethiopia

- Reports, studies and evaluations from various international organizations

- Publications from the Government of Ethiopia

Project Reviews: N = 45 projects

A review of project documents including approval documents, management summary reports, annual reports and other relevant documentation from:

- 35 bilateral development projects (WGM)

- 6 partnerships for development innovation projects (KFM)

- 4 global issues and development projects (MFM)

Case Studies

Two embedded case studies were done to inform the overall evaluation by providing more in-depth analysis of processes and identifying good practices and results for horizontal learning.

The case study on gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls was conducted jointly with the evaluation of Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women and Girls in the Middle East and the Maghreb, with a view to identify and better understand departmental structures, processes and tools for gender equality integration and how the change from a mainstreaming approach to a targeted focus has influenced programming and the achievement of results.

The case study on resilience-building examined how Canadian investments have contributed towards greater resilience for Ethiopians.

Interviews: N = 122 interviews, N = 291 respondents (175M, 116F)

Semi-structured individual and small group interviews were conducted with a variety of stakeholders in Canada and Ethiopia. This included current and former GAC staff and specialists (N=68), representatives of Canadian and local partner organizations (N=130), Ethiopian government officials and service providers at various levels (N=87), participants in Canadian-funded projects (N=7) and academic experts (N=1).

Milestone Mapping: N = 10 focus groups

A milestone mapping exercise was done through facilitated focus group discussions with Canadian implementing agencies, mission staff, thematic specialists, other donors and partners. It served to identify and better understand how various milestones, policies and/or events impacted Canadian international assistance programming, various stakeholders and/or results depending on the thematic focus.

Site visits

Site visits were conducted in Addis Ababa and three additional regions: Amhara (Bahir Dar), Tigray (Mekelle), SNNP (Hawassa, Sodo, Arba Minch).

This involved visits to project sites, as well as discussions with partners, local government stakeholders, service providers and beneficiaries in relation to 24 different projects.

Evaluation Limitations and Mitigation Measures

| Limitations | Mitigation Measures |

|---|---|

| Focus on bilateral programming in project sample: Due to the recently completed evaluation on Canada’s International Humanitarian Assistance (IHA), the evaluation scoped out this type of programming from the project sample in Ethiopia in order to limit the burden on staff and partners. In addition, a relatively high number of KFM and MFM projects (non-humanitarian) were implemented in multiple countries and with a limited project presence in Ethiopia, contributing to a smaller sample for the evaluation. |

|

| Data collection limited to four regions: Originally delayed from the fall of 2019 due to staff changes, the preparations for the data collection taking place in February 2020 were partly impacted by the limited availability of program staff to provide timely support and liaison with partners due to multiple high-level visits taking place. Because of time constraints, geographic spread of programming and security concerns, site visits were limited to four regions where the majority of Canadian-funded projects were implemented. |

|

| COVID-19 pandemic: While the evaluation covers the period up until end of March 2020, the evaluation report does not consider the impacts of COVID-19. Complementary data collection in additional regions (Afar, Benishangul-Gumuz) by local consultants had to be cancelled due to the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, availability by some staff and partners for interviews was also affected by the pandemic. |

|

Findings

Adaptability

Key Events and Milestones

2005 - Disputed general election: Protests erupted after allegations of vote rigging. As a result, ~200 people were killed and thousands imprisoned. Canada and much of the donor community suspended general budget support.

2009 - Charities and Societies Proclamation issued: Severe restrictions on CSOs issued, restricting their engagement in human rights advocacy and limiting funding from foreign sources to 10%. Many Canadian organizations switched to providing services to be able to continue operations.

2013 - Ethiopia Program’s 2013-18 Country Strategy adoptedCanada defined its main thematic priorities: food security, sustainable economic growth and advancing democracy.

2016 - Ethiopia suffered its worst drought in 50 years: 10 million people faced severe food insecurity due to El Niño. Canada’s humanitarian assistance and contributions to PSNP increased to respond to the crisis.

2016 - First state of emergency declared: Widespread protests lead to a year-long state of emergency. Restrictions were placed on freedom of movement and assembly. Telecommunications networks were frequently shut off, causing programming challenges.

2017 - Feminist International Assistance Policy adopted: Canada’s new international assistance policy introduced with a key focus on gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls. Most partners reacted positively. This coincided with a greater priority for Ethiopia.

2018 - Dr. Abiy Ahmed appointed PM: Ethiopia’s PM declared an end to the state of emergency and embarked on political and economic reforms. Canada discussed with GoE on how to best support its plan for a green economy and the upcoming elections, committing $1M in support of the latter.

2019 - New CSO Proclamation issued: Removal of foreign funding limitations on Ethiopian CSOs. Opportunities for advocacy in matters of human rights and gender equality opened up. This immediately impacted how Canadian organizations and their local partners can work together, including support to women’s organizations working on advocacy, using human rights-based approaches.

Adaptability

Aligning with Ethiopian priorities

Canada’s international assistance was aligned with the priorities of Ethiopia.

Throughout the evaluation period, there was a strong alignment between Canada’s international assistance and the priorities of Ethiopia. The Ethiopia Program was one of the few country programs with an approved Country Strategy (2013-18). This strategy and other strategic documents, were developed in consultation with the Government of Ethiopia (GoE) to directly respond to priorities laid out in the Growth and Transformation Plans (GTP I & II) and in contribution to the Sustainable Development Goals. Key common focus areas included improved food security and nutrition, including MNCH; increased agricultural productivity and market-oriented approaches; sustainable economic growth, including small business growth, extractive sector development and non-farm employment for youth; as well as contributions to an enabling environment by strengthening democratic institutions and citizen participation. These priorities and thematic areas were also closely aligned with Canadian policy and priorities prior to FIAP.

Text version

Growth and Transformation Plans (GTP I & II)

PSNP ← Increased food resilience and reduced vulnerability → Food Security

AGP SLMP ← Increased agricultural productivity → Agricultural Growth

Micro and Small Business Strategy ← Increased non-farm employment → Sustainable Economic Growth

GAC Program Priorities

The program portfolio was largely designed to complement Ethiopia’s flagship programs.

Throughout most of the evaluation period, two of Ethiopia’s flagship programs, e.g. the Productive Safety Net Program (PSNP) and the Agricultural Growth Program (AGP), were at the centre of the bilateral program’s portfolio design, directly supported by a number of additional projects, as reflected in its country strategy. For example, the Capacity Development Support Facility for AGP II offered technical assistance and targeted training to government officials at the national and regional levels, with a view to help them acquire the necessary capacity to manage these programs. The Capacity Building for Sustainable Irrigation and Agriculture project (SMIS) helped bridge previous financial support to the Sustainable Land Management Program (SLMP) by combining support for capacity building and provision of irrigation services. Other programming was closely aligned with the same objectives of increasing food security and supporting agricultural growth in a complementary manner to help ensure coherence and maximize impact, but limited evidence of co-operation between projects has been noted by the evaluation, likely due in part to the geographic spread of activities and project locations.

A weak private sector and poor investment climate remain critical economic growth barriers.

Canada’s support in the area of economic growth responded to evolving needs for increased non-farm employment and aligned with the GoE’s strategy to build micro and small businesses. Programming was designed to support an enabling business environment and to strengthen the natural resources sector and value-chains. It also had a strong component helping to improve economic opportunities and the financial inclusion of women, as well as on entrepreneurship and private sector development, focusing specifically on women and youth. Because of persistent challenges linked to investment climate and market linkages, initiatives for entrepreneurship and private sector growth remain small-scale.

Adaptability

Responsiveness to critical needs

Humanitarian Assistance has been timely and responsive to critical needs linked to droughts, flooding, conflict-related displacement and refugee needs.

Canada provided timely humanitarian assistance to respond to critical needs, targeting both Ethiopian beneficiaries and refugees. These contributions were significant, representing 22% of all disbursements during the evaluation period, and making Canada the 5th largest single-country humanitarian donor in 2019. Funding was channelled through trusted and experienced humanitarian partners in relation to droughts, flooding, intercommunal conflict and refugees living in the country. Following the major droughts of 2015 and 2017, it was also supplemented by additional bilateral contributions to PSNP through the crisis pool. The transition to provide multi-year humanitarian funding also allowed support to be more responsive to protracted crises.

Crisis Modifiers

An emerging best practice in bridging the humanitarian-development nexus is the use of crisis modifiers. This is a contractual tool piloted by USAID that allows donors to rapidly redirect development funds towards humanitarian activities. If certain conditions are met (e.g. conflict or natural disaster), funding can be rapidly shifted from development programming to humanitarian response. Crisis modifiers have been particularly important for USAID in Ethiopia, having been used since 2009 in several projects focused on building resilience.

Crisis modifiers have also been used by the U.K.’s Department for International Development (DFID) in Africa’s Sahel region, where they were built in from the outset as a form of contingency planning and were used to respond to natural disasters and conflict-related displacement in several countries. Experience shows that “when employed effectively, crisis modifiers offer a practical means to avert or reduce the impact of a crisis on beneficiaries and protect resilience trajectories.”

While Global Affairs Canada does not have crisis modifiers as a contracting option for its international assistance, similar approaches were used in Ethiopia.

During the evaluation, states of emergency and severe droughts posed significant operational challenges, including delays of funding disbursements and project approvals, which had a negative impact on affected local project partners and intended beneficiaries. However, there were notable examples of flexibility on the part of GAC to respond to emerging issues, including working closely with trusted partners to reorient development projects towards meeting immediate humanitarian needs. For example, the INSPIRE project, implemented by Save the Children in Afar and Amhara regions, both of which were heavily prone to drought, was authorized by GAC from the inception of the project to have some flexibility in its budget to respond to crises. The GROW project, implemented by Care Canada, was also allowed to reorient its activities to respond with a six-month Drought Response Plan to the El Niño drought.

Limited programming in the area of environment and climate action showed a gap in alignment with current Ethiopian priorities and needs.

Ethiopia is among the top ten countries in the world most vulnerable to climate change. Its policies and development plans reflect this, and the GoE has a strong focus on building a green and climate-resilient economy. While certain Canadian projects integrated environmental approaches and climate-resilient practices, Canada did not have a strong focus in this area in its overall portfolio. The recent support to the pooled funds for the Resilient Landscapes and Livelihoods for Women project (RLLP) shows an increasing commitment to do more. The Ethiopia Program has also commissioned a number of pre-feasibility studies in the areas of environment and climate change, irrigation and water, and nutrition in order to provide an evidence base to inform future programming in the sector.

Adaptability

Canadian priorities and policy changes

The increased focus on gender equality was mostly driven by changes in Canadian priorities and policy, but coincided with a greater commitment in Ethiopia.

Canada has been seen as a strong voice on gender equality in Ethiopia for many years, having contributed to incorporating gender considerations into national food security and agricultural growth programs. Canada has also been one of the key drivers in the donor community to put gender equality higher on the DAG agenda. With the introduction of the Feminist International Assistance Policy (FIAP) in 2017, the Ethiopia Program became more strategically focused on gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls. The program was also a key recipient of the Government of Canada’s funding commitment to help advance and address existing gaps in Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights (SRHR) and its Women’s Voice and Leadership (WVL) program. New programming in these areas has been aligned with recent efforts by the GoE to advance women’s empowerment and achieve gender equality through supportive policies, laws and institutions. Examples include a renewed commitment to end child and early forced marriage and female genital mutilation by 2025 and ongoing reforms toward a more open space for women’s organizations.

The adoption of FIAP saw a reorientation of thematic priorities and a stronger focus on gender equality integration in programming.

FIAP resulted in a shift from the previous departmental thematic areas to the FIAP Action Areas. Food security projects were redefined as either human dignity, growth that works for everyone, or even environment and climate change. FIAP also introduced commitments to increase Canada’s support for initiatives that advance gender equality and empowerment of women and girls as their principal focus, i.e. either specific (GE3) or integrated (GE2). Gender equality had been integrated in all programming as a cross-cutting theme before, but few projects had had this specific focus. The Ethiopia program saw an increase in GE3 projects from 0% in 2016-17 to 16% in 2019-20. Most Canadian implementing agencies welcomed the greater focus on gender equality in programming, and those that did not already have a strong gender focus took important steps for greater integration of this focus in programming. While access to tools and support by GAC staff and gender experts have been mentioned as contributing to making the shift easier, several respondents felt that the time between the introduction of the FIAP and making this support available was too long. The strong focus on gender equality coding targets introduced by FIAP was also a concern, especially for partners with programming in areas like natural resource management and governance. Many misconceptions on the use and interpretation of the coding also persists, as well as on what constitutes transformative change, a requirement for a GE3 project. As GAC’s Gender Equality (GE) Coding Framework criteria only assess projects for their potential contributions to gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls at the proposal stage, the efforts done by partners with projects approved before FIAP to strengthen this focus, even with resulting positive changes for women and girls, are not reflected in the GE coding.

text version

Figure shows the relationships between previous Global Affairs Canada’s thematic areas and the new FIAP Action Areas.

- Former thematic area “Sustainable Economic Growth” (Small Business, Extractive Sector) has a direct link with FIAP Action Area “Growth that Works for Everyone”.

- Former thematic area “Food Security” (Agriculture, Nutrition, MNCH) has been split between three FIAP Action Areas “Growth that Works for Everyone”, “Human Dignity” and “Environment & Climate Action”.

- Former thematic area “Advancing Democracy” (Federalism, Institutional Strengthening) is directly tied to FIAP Action Area “Inclusive Governance”.

All areas are connected to the crosscutting FIAP Action Area “Gender Equality and Empowerment of Women and Girls”.

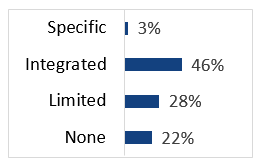

Total GE Integration (FY 2013-14 – 2019-20)

Text version

Specific: 3%

Integrated: 46%

Limited: 28%

None: 22%

WGM GE Integration (FY 2013-14 – 2019-20)

Version texte

Specific: 4%

Integrated: 55%

Limited: 15%

None: 26%

Adaptability

Factors affecting responsiveness and adaptability

Good practices for improving team effectiveness

In order to bridge common challenges linked to staff turn-over, the Ethiopia Program established a system of shared roles and responsibilities and good information management practices between HQ and mission. Detailed hand-over notes and ever-green briefing products linked to all key programming areas have also helped in this regard. The program also developed useful tools for oversight and coordination of programming, including a comprehensive mapping of projects from all branches. Yearly planning sessions with integrated planning practices, supported by FSSP specialists, were also useful in improving coordination. They were supported by thematic analysis and pre-feasibility studies to ensure alignment with needs and priorities in programming.

Because of the importance of Ethiopia for Canadian international assistance programming and its role in the region, the mission is used to frequent high-level visits. While often demanding both in terms of time and special skills, these visits have been seen as good opportunities to break silos between development, trade and diplomacy.

Continued support to the GoE’s flagship programs and active involvement in the DAG helped establish Canada as a trusted partner in Ethiopia.

Canada’s long-standing financial and technical support to the GoE’s flagship programs, in particular the PSNP and the AGP, provided a foundation for meaningful policy dialogue and served to position Canada as a trusted partner in Ethiopia. Active participation in the Development Assistance Group (DAG) also helped Canada coordinate and to speak with a common voice with other like-minded donor countries vis-à-vis the GoE.

Mandatory registration of projects and ongoing oversight by government officials contributed to making Ethiopia an active partner in programming and local ownership of results.

In line with aid effectiveness principles, the GoE has taken a strong position in overseeing foreign development cooperation. Canada’s annual bilateral consultations have been important to ensure programming is aligned with Ethiopian priorities and needs. The need for partners to register projects with officials at regional and local levels also helped ensure alignment with priorities and supported coordination, oversight and multi-stakeholder involvement by key service providers, in addition to promoting local ownership of results.

In order to adapt programming to the needs of beneficiaries, many implementing partners worked through local partner organizations and extension services.

Because of Ethiopia’s vast geographic spread and enormous variations in agro-ecology and livelihoods, as well as its linguistic and ethnic diversity, programming cannot take a one-size-fits-all approach. Many implementing partners were present in more than one region and in multiple locations within a region. To bridge various regional differences and to target programming to needs of beneficiaries, several partners worked through locally based organizations and service providers. CANGO, a well-established network of Canadian NGOs working in Ethiopia, has been an important forum for exchanges on programming challenges, lessons learned and best practices, as have the regular meetings organized by the Canadian embassy with Canadian partners.

Canada has had limited opportunities to support recent economic and political reforms.

During the evaluation period, the Ethiopia program’s budget was highly committed to multi-year programming developed in support of its 2013-18 Country Strategy. This, in combination with common corporate barriers linked to lengthy approval and contracting processes, made it difficult to rapidly put in place projects to respond to emerging priorities and opportunities in relation to the GoE’s new economic and political reforms. New funding during the period was primarily tied to SRHR and WVL commitments, apart from a recently approved support for the upcoming elections. Towards the end of the evaluation period, with several projects recently ending or coming to an end, the Ethiopia Program has started exploring how to align future programming with the current GoE’s reform agenda, while building on current successes and lessons.

Results

Agriculture

Agriculture represents close to 45% of GDP and employs 85% of the population. The majority of people working in agriculture are smallholder farmers with low levels of capital inputs. The agricultural sector faces ongoing challenges related to the availability of land, desertification and degradation due to over cultivation, climate change and limited access to markets for rural producers, of which close to 50% are women.

Agriculture continued to be a major focus for Canada’s programming in Ethiopia.

Agriculture represented 24% of all programming disbursements in Ethiopia during the evaluation period, as per DAC sector coding. Programming was designed to support AGP objectives, with a strong focus on promoting research and new technologies to introduce new and improved crops; strengthening farmers’ skills and knowledge of more productive and climate-resilient agricultural practices; diversifying livelihoods; and strengthening farmers’ participation in agricultural value chains. In addition to strengthening the GoE’s own capacity in relation to AGP II, programming also contributed to strengthening capacities in the agricultural sector more broadly by working with select Technical and Vocation Training Institutions (TVET) to modernize their curricula and introducing a gender-responsive approaches. Canada’s support also contributed to the adoption of a participatory irrigation development and management approach in all regions, in addition to providing irrigation and drainage to 20,436 hectares of land, benefiting over 71,000 water users.

Support to smallholder farmers contributed to increased productivity and household incomes but remained localized due to weak value-chains and market links.

The majority of project beneficiaries were smallholder farmers in rural communities. During the evaluation period, a greater focus was put on supporting female-headed households, as there are still several barriers for women to access productive resources such as land, finance, irrigation, modern inputs and technology suitable for their needs. This remains a critical area for support.

Programming contributed to enhancing productivity by promoting innovation and helping producers expand beyond an exclusive focus on cereal crops. New varieties like chickpeas were introduced, as well as crops that can be harvested multiple times each year. Farmers started growing vegetables, selling livestock, eggs, dairy products, honey and other higher-value products. This contributed to increasing household incomes. For example, Care’s Food Self-Sufficiency for Farmer’s project succeeded in increasing the incomes of participating households from a baseline average of $362 to $614. Female-headed households saw an even greater improvement, going from $284 to $564. Canadian agriculture programming also aimed at improving farmer households’ nutrition and resilience to climate change. This included more efficient and climate-resilient agricultural practices, for example, conservation agriculture and vertical farms. New crops were introduced that were more resilient to climate stresses and/or had higher nutritional value than traditional crops. The success of these efforts was, however, mixed; in some cases, the commercial viability of these new crops was questionable, given limited market demand and government buy-in.

While several successes have been noted, much of the impact has remained at a localized level due to continued weak value-chains and market linkages, with limited capacity to scale up. Diverse geographic needs and continued vulnerability to climate-related events also affected sustainability of interventions.

Photo:

Photo of a woman in front of a pile of rice bags.

Fikradis Getnet, a 42-year-old rice producer from Woreta, Amhara, received training through the Value Chains for Growth project that increased her knowledge of rice processing and marketing, allowing her to develop market linkages to Addis Ababa.

Photo credit: MEDA

Results

Food Security

The Poverty and Safety Net Program (PSNP)

The Ethiopian government launched the PSNP in 2005 as a social protection program targeting food-insecure households. The PSNP supports approximately 8 million food insecure households every year with transfers of cash or food. In return, recipients contribute to labour-intensive public works projects such as roads, dams or tree planting. Evaluations have shown that the program has succeeded in improving household food security, and has played an important role in mitigating or averting humanitarian crises.

Canada’s long-standing support to the PSNP contributed to Ethiopia’s development priorities and supported vulnerable populations in food-insecure districts.

Canada contributed directly to the program design of the PSNP, and has also been one of the largest single-country donors since the program’s inception. It represents the largest investment of the Ethiopia bilateral development assistance program, corresponding to 37.7% of all WGM disbursements, with funds channelled through the World Bank and the United Nations World Food Programme (WFP) to the multi-donor pooled funds for the PSNP. While Canada helped promote a greater focus on gender equality linked to PSNP through its participation in the DAG, it remains a challenge to attribute specific results linked to Canadian contributions to un-earmarked multi-donor programming. However, Canada directly supported Phase III of PSNP with a well-received technical capacity-building project for government officials, which included gender mainstreaming. By the end of 2021, it is estimated that Canada will have contributed $491.6M to PSNP. While Canada’s support to PSNP has been instrumental in supporting the poorest and most vulnerable in many food-insecure districts, it doesn’t extend its services to refugees residing in the country.

While being seen as a model project for social protection in Africa, the PSNP has experienced challenges with achieving some of its intended goals.

The PSNP has made notable contributions to building household resilience to shocks. However, the stated objective for PSNP beneficiaries to eventually “graduate” from the program has been difficult to achieve. Reoccurring droughts, poor harvests and increased prices have contributed to putting some beneficiaries back into food insecurity. To enhance the prospects for graduation, PSNP IV included a livelihoods component with training and access to finance to help poor households increase their incomes. Ultimately, the livelihoods component fell short of expectations. Underfunding meant that very few beneficiaries were able to participate, and those that did were reluctant to take on micro-loans given their inherent vulnerability. A recent review by the Government of Ethiopia and the FAO found that of the more than 315,000 households that completed the livelihoods component of PSNP IV, only 14% graduated.

Complementary projects have provided important linkages between agriculture, nutrition and access to finance, closely aligned with PSNP objectives.

Projects like Food Self-Sufficiency for Farmers and the Benishangul-Gumuz Regional Food Security Program were complementary to the PSNP by targeting food-insecure communities through a combination of activities linked to food production, improved nutrition, access to finance and livelihoods. The strong focus on establishing and strengthening community-level groups, building capacity for government officials and supporting them to work together to address common challenges have been successful in building local ownership. They have also helped raise awareness about improved agricultural practices, nutrition, environmental protection, gender equality and disaster risk management. Special attention was also given to address gender barriers and food taboos.

Photo:

Woman with a baby holding a PSNP Pamphlet.

Photo credit: The Embassy of Canada to Ethiopia Facebook

Results

Nutrition, MNCH and WASH

There are strong links between nutrition, maternal and newborn child health, and water and sanitation in Ethiopia. These are particularly important issues for women and children. According to UNICEF, 28% of child deaths are associated with undernutrition. Diarrhea claims the lives of 70,000 Ethiopian children each year, and nearly 39% of rural households still practise open defecation.

Complementary interventions in nutrition, MNCH and WASH have contributed to improving the overall health of women and children.

Ethiopia was a priority country for funding commitments under the Muskoka Initiative for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health (MNCH), with programming supported by GAC’s three main program branches (WGM, KFM, MFM) often making strong linkages between improved nutrition, MNCH and WASH. Canadian programming helped to improve nutrition for mothers and children through supplemental feeding and micronutrients, including providing over 3 million children with Vitamin A supplement. It also enabled 365,000 children to get treatment for acute malnutrition. Training on dietary diversity and agricultural productivity equipped households with the knowledge needed to expand and diversify their intake of healthy foods, improving dietary diversity scores for AGP II participants by 24%, and by 70% among children.

Programming increased the usage of MNCH services and improved the quality of care in government-run health facilities.

Ethiopia is notable for having achieved its Millennium Development Goal targets of reduced maternal and under-5 mortality. Several projects worked within the existing health system to improve the quality of care for pregnant and lactating women. This included supply-side interventions, such as encouraging delayed cord clamping, exclusive breastfeeding, and building the capacity of midwives. Programming also sought to increase demand for MNCH services, with several projects reporting increases in the number of women delivering safely in health facilities with a skilled attendant. In some cases, this number rose from 36% to 60%. Continued challenges to increase attendance at antenatal checkups can partly be attributed to the lack of rural roads and distance to health facilities, but was also tied to socio-demographic factors and traditional household roles. Mitigation strategies by some projects included encouraging men to attend visits with their wives and stronger involvement of men and boys in household chores. Sustainability was also a concern for MNCH interventions, particularly in rural areas where health facilities and extension services continue to rely on donor support.

Projects contributed to expanding access to clean water and improved sanitation.

A number of projects improved access to clean water and sanitation facilities, constructing water points in communities and health facilities. For example, water schemes installed by Save the Children’s INSPIRE and Care’s GROW projects have benefited over 215,000 people. Expanding WASH facilities has helped to reduce open defecation. For example, UNICEF’s Improved Food Security for Mothers and Children project supported over 36,000 households to construct latrine facilities, leading to nearly 500 villages being declared “open defecation free.”

Photo:

Two young Ethiopian girls washing their hands.

Several Canadian organizations worked together to improve the delivery of health services to women and young children, including Children Believe and Amref, in the joint Canada-Africa Initiative to Address Maternal, Newborn and Child Mortality (CAIA-MNCM) project.

Photo credit: Children Believe

Results

Economic Growth

Despite a high rate of GDP growth, Ethiopia’s private sector is constrained by several factors. These include a weak financial system, foreign currency shortages, limited access to inputs, and complex regulations and tax systems. Ethiopia’s Plan of Action for Job Creation estimates that 14 million jobs will need to be created between 2020 and 2025 to absorb new entrants to the labour market and those currently unemployed.

Economic growth programming helped to generate new business and employment opportunities. The focus on entrepreneurship benefited youth and women in particular.

Canada’s economic growth programming was focused on creating off-farm employment opportunities, particularly for young men and women. Programming helped to create thousands of new businesses and jobs by providing training and start-up capital. Programming, for example DOT’s Entrepreneurship and Business Growth for Youth project, also developed “soft skills” for youth through training, networking, mentorship opportunities and “women in business” events. In addition to training tens of thousands of Ethiopian youth, the project has helped to create over 5,900 new businesses, 63% of which were female-owned. Most of the job creation efforts focused on micro and small enterprises, with one or just a few employees. While these provided important entry points for women and youth, they have to date had limited potential for large-scale job creation and income generation. A growth mindset is still lacking, tied to a poor investment climate and weak enabling business environment to sustain this practice.

Programming contributed to greater access to financing for small and medium enterprises, the so-called “missing middle”.

Programming has helped to link participants to different sources of finance, ranging from small-scale community savings groups or microfinance institutions, to banks and more innovative sources of finance, like the angel investor network of RENEW’s Accelerating Business Growth project. Participants also developed financial management skills to properly manage funds. Several projects succeeded in increasing access to finance for women, including the World Bank’s Women’s Entrepreneurship Development Program, which provided business loans valued at $42M to over 2,500 women. MEDA’s Value Chains for Economic Growth project used an innovative credit risk partnership with Bunna Bank to offset some of the perceived risk of providing credit to women.

Photo:

Factory employees sewing.

Desta PLC is a garment company that has received support from angel investors linked to RENEW’s Accelerating Business Growth project. 90% of its employees are women, and it aims to ensure that 5-10% of its labour force are people with disabilities.

Photo credit: The Embassy of Canada to Ethiopia Facebook

Ethiopia’s investment climate remains challenging. Canada’s contributions to the enabling environment were largely concentrated in the natural resources sector.

While Canada contributed to job creation, the conditions for private sector growth in Ethiopia remain challenging. This is particularly true outside of major cities, where agriculture remains the main livelihood. Ethiopia’s GTP II identified the extractive sector as a potential source of off-farm employment. Programming contributed to building the enabling environment for mining by introducing technical and vocational training programs, as well as a new mining cadastre system that streamlines data and regulations between the federal and regional governments. Beyond the mining sector, support to the International Finance Corporation contributed to streamlining taxation and business registration systems.

Results

Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women and Girls

Ethiopia has a strong legal and policy framework for gender equality, and conditions have improved over the last decade. Nonetheless, there are persistent disparities in labour force participation, access to resources, and political representation for women. Child and early forced marriage (CEFM), female genital mutilation (FGM) and other forms of gender-based violence are very common in several regions, often tied to social norms and traditional practices.

Existing partners embraced the FIAP and altered their ongoing projects to better focus on gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls.

Much of the programming during the evaluation period was developed with gender equality being a cross-cutting issue. The adoption of FIAP provided an impetus to strengthen the gender lens in all programming. Many partners chose to revisit their project designs to not only focus more on women and girls, but to make activities more accessible and inclusive. This included revised enrollment criteria to better include women, ensuring that training opportunities were conveniently located and childcare provided.

Projects helped to generate new or improved economic opportunities for women and facilitated their participation in income-generating activities.

New or improved economic opportunities for women have been created through targeted programming, like the World Bank’s Women’s Entrepreneurship Development Program, and through the efforts of other economic growth projects to specifically support women. There have also been efforts to introduce technologies that can enhance women’s participation in agriculture. For example, Canada’s support to AGP II saw the introduction of over 70 gender-sensitive technologies that saved time and labour for female farmers.

Challenges remain to achieve more transformative changes for gender equality, especially linked to SRHR and SGBV.

The most commonly reported result during the evaluation period was increased awareness of gender equality among households. Some changes in behaviour were also noted at the household level, such as an increase in sharing of tasks, improved relationships and more open communication between participating husbands and wives. The Gender Model Family approach to help evaluate the distribution of household responsibilities, introduced by the SMIS project, was subsequently endorsed by the SNNP regional Bureau of Agriculture.

Canada’s support to women’s sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) is still in the early years of implementation, but there have already been some promising contributions to reduce CEFM, FGM and other forms of sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV), in addition to multi-faceted support to victims. However, given the scope of gender equality issues in Ethiopia and remaining barriers for women’s social, economic and political inclusion and access to resources, transformative changes for women and girls are still difficult to achieve. Project durations are often insufficient to fully address associated social norms, which often vary from region to region. Work with allies, including religious and traditional leaders and other change agents in a community setting, was seen as a good practice. However, the evaluation noted a gap in addressing some of the underlying economic causes of many of these practices and the expectations raised by the interventions, as few connections to job opportunities exist for young women and men in the areas where the projects take place, especially in rural areas.

Photo:

Women using rotary weeding tools to tend to their rice crops.

MEDA’s Market-Based Solutions for Improved Livelihoods project introduced rotary weeding tools to reduce the time and physical effort required for women to tend to their rice crops.

Photo credit: MEDA

Results

Governance and Human Rights

Ethiopia has adopted a system of ethnic federalism, with the country divided into 9 regions. Since 1991, the ruling party has traditionally been composed of a multi-ethnic coalition of political parties. PM Abiy’s appointment in 2018 led to economic and political reforms that are seen as a threat by politically dominating and resource-rich regions. Calls for more independence and rising political tension have led to increased violence, postponing the planned elections on numerous occasions.

Canadian support is helping shape a new model of revenue sharing between regions in Ethiopia’s ethnicity-based federal system and in strengthening of public service.

While the governance portfolio was relatively small, it had a strong focus on contributing to strengthening Ethiopia’s federal system and the House of Federation, its parliamentary system’s upper house and oversight body, through the Strengthening Federal Governance and Pluralism project. This project was directly aligned with the GoE’s priorities to strengthen democracy and good governance, and more specifically intergovernmental relations between the country’s regions, which is a sensitive issue because of its federal model based on ethnicity. The project helped shape the approach to concurrent revenue sharing between the federal and regional governments, taking into account disparities between regions in terms of access to resources, including oil revenues. Gender-equitable distribution and environmental sustainability are important considerations. In light of the continued political violence, especially in regions that could potentially lose some of their previous political influence, the evaluation noted a need to integrate a stronger conflict lens in governance programming.

Through its technical assistance to the GoE’s flagship programs, Canada’s support contributed to building a stronger public service. However, challenges with turnover, staff retention, interdepartmental coordination and information sharing remain. Other support contributed to the International Finance Corporation streamlining taxation and business registration systems, making it easier to conduct business and international trade. Canada is also working closely with the National Election Board of Ethiopia and will be providing support via UNDP to strengthen its capacity and independence for the upcoming general elections. However, increasing ethnic tensions are putting important progress at risk.

Photo:

Canada’s Prime Minister Justin Trudeau in conversation with Ethiopia’s President, Sahle-Work Zewde.

Sahle-Work Zewde is the first woman to hold the position of president of Ethiopia. While women’s political representation is an ongoing challenge, PM Abiy has appointed a gender-balanced cabinet, with women occupying key postings like defence, trade and labour.

Photo credit: Office of the Prime Minister of Canada

Recent civil society reforms provide increased opportunities for advocacy and human rights-based approaches.

The 2009 Charities and Societies Proclamation limited the ability of international donors to support local civil society financially and placed considerable restrictions on human rights advocacy. As a result, many CSOs, including women’s rights organizations, were forced to move away from rights-based work to focus on service provision. Recent political reforms have generated cautious optimism among members of civil society. The 2019 CSO Proclamation that lifted these restrictions, and set clear statements in support of gender equality, presented opportunities to strengthen advocacy for human rights and inclusive approaches for governance in the future. Canada’s support through Plan International, under the Women’s Voice and Leadership initiative, focuses on strengthening women’s organizations to empower women and girls and to advocate for their rights in an environment free from violence, harmful practices, exploitation and discrimination. While more confident, many of these women’s organizations have been weakened by the long-lasting restrictions, so this support is very timely.

Results

Factors for Success

Engagement with the Public Sector

- Ethiopia’s public sector is professional and development-oriented, willing to actively participate in project activities.

- Projects often engaged government actors through policy dialogue, as steering committee members or as partners in delivering activities. Working with or through government systems enhanced the prospects that activities would be sustainable.

Community-based approaches and engagement with local stakeholders

- Participatory design was important in building ownership and ensuring that project activities were relevant to local priorities. Strong relationships with local partners contributed to these exchanges.

- Agriculture projects used a participatory variety selection approach, where target communities could test out new crops and provide feedback on what characteristics mattered to them.

Multi-faceted and multi-sectoral approaches

- Ethiopia is increasingly stressing multi-sectoral collaboration around key issues. For example, the National Nutrition Program is being led by the Ministry of Health alongside eight other government ministries.

- Projects that made connections between intervention areas, like agriculture and economic growth, or nutrition, MNCH and WASH, while working with government partners and supporting interdepartmental collaboration, were able to have a greater impact.

Challenges

Changing context due to civil unrest and climate change

- Two states of emergency, recurring droughts and political volatility made for a challenging context for international assistance programming.

- Some projects experienced delays or even material losses as a result of these events.

- Much of Canada’s programming focused on agriculture, a sector that is highly exposed to the effects of climate change.

Weak private sector and market linkages

- A continued weak private sector, business environment and infrastructure, especially in rural areas, made it difficult for projects to build value chains and to link micro, small and medium businesses to markets.

- Support to smallholder farmers, entrepreneurship and new businesses therefore remained small-scale.

- The commercial viability of new and innovative initiatives is also affected by a poor investment climate.

Social norms create barriers for achieving results for women and girls

- Social norms play a significant role in influencing opportunities for women and girls in Ethiopia’s highly patriarchal and conservative society. In a country as diverse as Ethiopia, these social norms are also significantly different from region to region.

- Partners often found it challenging to raise awareness and address discriminatory and harmful practices within the timelines of a regular project, while also providing sustainable options linked to the underlying causes.

Innovation

The Ethiopia Program featured many encouraging examples of using innovation to enhance international assistance. The most promising examples, and those with the greatest potential for sustainability, had strong linkages to markets and the public sector.

In line with the Whistler Principles to Accelerate Innovation for Development Impact, bilateral and KFM programming in Ethiopia has created supportive conditions for innovation. Creative partnerships with research institutes, both locally and internationally, were used to develop new ideas that could address Ethiopian development issues. Some innovations proved more successful than others. Commercial viability, local preferences, and the support of government institutions were important factors for successful innovation.

Offering a Platform for Innovation

The Entrepreneurship and Business Growth for Youth project brought young people together to propose innovative businesses. DOT provided training and support to develop these ideas.

RENEW’s Accelerating Business Growth project supported Chigign ‘Tobiya, a television program where entrepreneurs present business ideas to a panel of investors. This popular program is helping to normalize entrepreneurship as a viable option for pursuing a livelihood.

Photo:

Young people participating in a training activity.

Photo credit: DOT Facebook

Integrating Science and Technology

KFM and IDRC funded research to introduce new varieties of pulses and other seeds in southern Ethiopia that were more drought and flood resistant, contributing to more reliable crops.

Through the Support for the Ministry of Mines project, Ethiopia developed a sophisticated mining cadastre system. This comprehensive geological survey has an online interface that allows stakeholders to engage with the Ministry directly, and harmonizes a number of different data sources and regulations.

Simple Solutions to Local Problems

The Canada-Africa Initiative to Address Maternal, Newborn and Child Mortality recognized that in mountainous parts of Amhara region, pregnant women relied on crude stretchers to take them to health centres to deliver. The project introduced a lightweight metal version that was safer and more comfortable.

The Capacity Development for Sustainable Irrigation and Agriculture project introduced vertical farming using discarded plastic bottles.

Photo:

Photo 1: Pregnant woman on a basic and heavy stretcher in wood.

Photo 2: Lightweight metal version stretcher.

Photo credit: Children Believe

Climate and Resource Smart Agriculture

The Canadian Foodgrains Bank’s Scale-up of Conservation Agriculture in East Africa project promoted the conservation agriculture approach in several regions of Ethiopia. This is a low-tech, principles-based approach to farming that focuses on promoting biodiversity and minimizing soil disturbance, especially embraced by female farmers. The project helped to increase farmers’ productivity, but also the health and fertility of their soil. As a result of policy dialogue efforts, this approach has been endorsed by the federal government.

Photo:

A woman standing in a field.

Photo credit: Evaluators

Good Practices for Sustainability

Generating Incomes to Sustain Impact

The Agricultural Transformation Through Stronger Vocational Education (ATTSVE) project, implemented by Dalhousie University, focused on improving the quality of education at four agricultural colleges, helping to develop highly skilled future workers and promote innovative approaches. The project also introduced new equipment and tools, e.g. new dairy barns and milking machines. In addition to providing hands on learning opportunities for students, these income generating activities were also intended to support ongoing improvements at the colleges and to improve self-sufficiency.

Multifaceted approach to address SRHR

UNFPA’s Preventing and Responding to Sexual and Gender-Based Violence project has taken a multi-faceted approach to raise awareness on addressing CEFM, FGM, SGBV and SRHR by fostering dialogue between communities, local authorities and vulnerable households. It has provided training to government extension workers, health personnel and law enforcement bodies to improve service provision and implementation of legal and policy frameworks. In addition, it has provided a comprehensive and integrated support to victims of SBGV through a network of safe houses, model clinics and one-stop service centres.

Model for Building Government Capacity

Alinea International (former Agriteam) was a key partner in building capacity of government officials and extension workers to deliver Ethiopia’s flagship programs PSNP and AGP. Its four 4-step capacity development model was well-received by Ethiopian government partners. Alinea used adult education principles to make training more practical, identified master facilitators to help cascade learning to government partners, and developed a number of training and knowledge resources, including on gender equality, subsequently adopted by the GoE.

Addressing Ethiopia’s “missing middle”

RENEW’s Accelerated Business Growth (ABG) project used a unique blended finance model to help SMEs, Ethiopia’s so called “missing middle”, access finance from a growing network of domestic and international angel investors committed to building Ethiopia’s economy. A special focus was put on women-owned and managed companies, complemented by a ‘Women in Finance’ training series aimed at empowering and inspiring women finance professionals. The project also offered Executive Programs training with modules on promoting gender equality and improving good governance and financial capacity of SMEs.

Working with Allies and Change Agents

Several projects in Ethiopia demonstrated the value of working with allies and change agents, including community and religious leaders, traditional birth attendants, women and youth organizations and schools to achieve positive changes in behaviours and to advance gender equality. Certain projects targeted men and boys specifically, important in a conservative society like Ethiopia. Men were encouraged to model positive masculinity, engage in household chores and support their wives. Religious leaders contributed by preaching against child marriage in their congregations.

Community-based savings models

Village Savings and Loan Associations (VSLA) and other community-based savings groups were used by several projects to offer households or groups of women a safe way to save money and access loans. In some cases, this helped fund major household purchases, like livestock, and contributed to households being more food secure and better able to withstand shocks, and thus helped build sustainability for the future. Community-based models also helped reduce some of the stigma and risk associated with individual loans, in addition to enabling a greater impact in the whole community.

Resilience

Resilience in Ethiopia

Resilience can be described as: The ability of individuals, households, communities, institutions and/or nations to cope with and recover from shocks or stresses linked to man-made events (political unrest, violence, conflict, financial crisis, etc.) or natural disasters (drought, flooding, earthquakes, etc.). It also means adapting and transforming structures to better withstand them, and is hence closely interlinked with sustainability measures.

The resilience paradigm is highly relevant in Ethiopia and reflected in GoE priorities.