North America Free Trade Agreement

Chapter 11 - Investment

Windstream Energy LLC v. Government of Canada

In the Matter of an Arbitration Under Chapter Eleven of the North American Free Trade Agreement and the UNCITRAL Arbitration Rule

Between:

Windstream Energy LLC v. Government of Canada

Claimant

And:

Government of Canada

Respondent

Government of Canada

Counter-Memorial

January 20, 2015

Sections and excerpts identified as "[REDACTED]" represent redactions in the official version of this document.

Please see Canada's Counter Memorial (PDF - 4.29 MB)

Trade Law Bureau

Departments of Justice and of

Foreign Affairs, Trade and

Development

Lester B. Pearson Building

125 Sussex Drive

Ottawa, Ontario

K1A 0G2

CANADA

Table of Abbreviations

- ADM

- Assistant Deputy Minister

- AOR

- Applicant of Record

- APRD

- Approval and Permitting Requirements Document for Renewable Energy Projects

- BRG

- Berkeley Research Group

- CanWEA

- Canadian Wind Energy Association

- CES

- Clean Energy Supply

- COD

- Commercial Operation Date

- CSA

- Canadian Standards Association

- DM

- Deputy Minister

- DOE

- Department of Energy

- EA

- Environmental Assessment

- EAASIB

- Environmental Approvals Access and Service Integration Branch

- EAB

- Environmental Approvals Branch

- EBR

- Environmental Bill of Rights

- EPA

- Environmental Protection Act, R.S.O. 1990, c. E.19

- ERA

- Electricity Restructuring Act, 2004

- ERT

- Environmental Review Tribunal

- FET

- Fair and Equitable Treatment

- FIT

- Feed-in Tariff

- FTC

- Free Trade Commission

- GBS

- Gravity Base Structure

- GEGEA

- Green Energy and Green Economy Act, 2009

- GEIA

- Green Energy Investment Agreement

- GLWC

- Great Lakes Wind Collaborative

- GLWQA

- Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement

- HONI

- Hydro One Networks Inc.

- HST

- Harmonized Sales Tax

- IBA

- International Bar Association

- ICJ

- International Court of Justice

- IESO

- Independent Electricity Supply Operator

- IJC

- International Joint Commission

- ILC

- International Law Commission

- ISO

- International Organization for Standardization

- LEEDCo

- Lake Erie Energy Development Corporation

- LTEP

- Long-Term Energy Plan

- MBCA

- Migratory Birds Convention Act, 1994

- MCOD

- Milestone Date of Commercial Operation

- MEI

- Ministry of Energy and Infrastructure

- MMAH

- Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing

- MNR

- Ministry of Natural Resources

- MOE

- Ministry of the Environment

- MTC

- Ministry of Tourism and Culture

- MW

- MegaWatt

- NAFTA

- North American Free Trade Agreement

- NPA

- Navigation Protection Act, R.S.C., 1985, c. N-22

- NTP

- Notice to Proceed

- OEB

- Ontario Energy Board

- OPA

- Ontario Power Authority

- PCIJ

- Permanent Court of International Justice

- PDR

- Project Description Report

- PLA

- Public Lands Act, R.S.O. 1990, c. P.43

- PO

- Premier’s Office

- PPA

- Power Purchase Agreement

- REA

- Renewable Energy Approval

- REA Regulation

- Environmental Protection Act, R.S.O. 1990, c. E.19, O. Reg. 359/09

- REFO

- Renewable Energy Facilitation Office

- RES

- Renewable Energy Supply

- RESOP

- Renewable Energy Standard Offer Program

- RFP

- Request for Proposal

- RFQ

- Request for Qualifications

- SARA

- Species at Risk Act, S.C. 2002, c. 29

- SOI

- Statement of Intent

- TSA

- Turbine Sales Agreement

- WEI

- Windstream Energy Inc.

- WWIS

- Windstream Wolfe Island Shoals Inc.

Introduction

I. Overview

1. The development of an offshore wind facility is an inherently “high-risk” activity. Today, only nine fully commissioned offshore wind facilities with a capacity of 300 MW or more exist in the world, all of them in Europe, and none of them in a freshwater environment. Not a single offshore wind facility is operational in North America.

2. The reason why there are so few operational offshore wind facilities is simple. Developing one requires overcoming significant challenges with respect to getting financing, obtaining access to a site, connecting to the electricity grid, conducting relevant research, acquiring the requisite permits, obtaining the necessary equipment and expertise, and securing onshore and offshore facilities to support construction. Most importantly, though, it requires time – particularly if it is a novel type of project, such as a freshwater wind facility, or first-of-a-kind project in a jurisdiction. The proponent requires enough time to ensure that it has gathered the relevant information, done the appropriate studies, obtained the necessary financing, consulted with all relevant stakeholders, and constructed the project efficiently, safely and properly. The regulatory authorities also need sufficient time to understand and evaluate all of the potential effects of the proposed project, and to develop the regulatory standards, guidelines and permitting requirements necessary to protect people and the environment from harm or interference through appropriate mitigation measures. Such timeframes for both the proponent and the government regulators are measured in years, not months. North America’s most advanced offshore wind project, the Cape Wind project, remains unconstructed more than a decade after filing for its initial permits.

3. Time is ultimately what this claim is about, and in particular, the time that the Government of Ontario requires to develop the regulatory framework necessary to assess the Claimant’s proposal to construct the first ever large-scale freshwater wind facility in the world. Put differently, this dispute is about whether Ontario has the right to proceed with caution when determining how to assess an activity that has never been attempted before and which would have uncertain effects on the Great Lakes environment and the millions of people who depend on it. The Claimant alleges that the fact that the Government of Ontario did not complete all the work necessary to develop the regulatory framework by May 4, 2012 violates Canada’s obligations under the NAFTA. The Claimant is wrong. NAFTA does not prohibit reasonable regulatory delays, which the Claimant deems unreasonable due to its own risk taking.

4. In 2007, the Claimant invested in Ontario with the idea of erecting a wind facility on the shoals off of Wolfe Island in Lake Ontario (the “Project”). At the time, the Ministry of Natural Resources (“MNR”) was not accepting applications for Crown land for offshore wind projects, the Ontario Power Authority (“OPA”) had no program to procure energy from offshore wind projects, and the Ministry of the Environment (“MOE”) had no regulatory process applicable to the environmental review of offshore wind projects that streamlined the necessary approvals.

5. Apparently undeterred by these risks, when the opportunity to apply for Crown land opened in 2008, the Claimant seized it. On February 20 and June 30, 2008, the Claimant applied for Crown land on the lakebed near Wolfe Island and Amherst Island in Lake Ontario for the purposes of developing its proposed offshore wind facility. A portion of the Crown land making up the Claimant’s application was situated in the narrows between Kingston and Wolfe Island. The rest extended out from Wolfe Island towards the U.S. border.

6. The Claimant was not the only prospector of renewable energy projects on Crown land. At $1,000Footnote 1 per Crown land application, the cost of applying was hardly a deterrent. The Claimant’s Crown land applications were among over 500 that MNR received by December 2008, 144 of which were to develop offshore wind farms. In the end, 16 different proponents had applied for Crown land to develop a total of 35 offshore wind projects. However, the OPA still had no program for procuring energy generated from offshore wind facilities, and there was no streamlined regulatory approval process in place specific to offshore wind development.

7. In 2009, the Green Energy and Green Economy Act, 2009 (“GEGEA”) was introduced by the Government of Ontario. The GEGEA had numerous broad goals related to renewable energy and conservation, but of particular relevance to this case are two of its initiatives. First, the GEGEA paved the way for the OPA to establish a Feed-in Tariff (“FIT”) Program in Ontario. This procurement program for renewable energy provided standard program rules, standard contracts and standard pricing based on classes of generation facilities. Under the FIT Program, the OPA would not assess the feasibility of the project. Instead, it would offer a FIT Contract to a proponent if there was sufficient capacity at the proponent’s proposed connection point to accommodate the amount of electricity that it proposed to provide. A FIT Contract provided no guarantee that a project would actually proceed or that necessary permits would be granted. It was left entirely to proponents to “navigate through the regulatory approvals necessary to bring their projects to life”. Footnote 2 Second, the GEGEA consolidated many of the provincial environmental approvals for renewable energy projects into a streamlined approval known as the Renewable Energy Approval (“REA”), and made MOE the primary regulator.

8. When the OPA launched the FIT Program on October 1, 2009, it was flooded with hundreds of applications for FIT Contracts. Yet, only two proponents applied for offshore wind projects. Thus, only two of the 16 proponents that applied to MNR for Crown land to develop offshore wind projects by December 2008 applied for a FIT Contract, despite the fact that seven of them had already obtained Applicant of Record (“AOR”) status and were therefore eligible to proceed to the permitting stage. The lack of interest in the FIT Program for offshore wind development was not a surprise. With no experience having been built up in the province (or in North America), neither industry nor the Government of Ontario was ready.

9. The Claimant was one of the two proponents to apply under the FIT Program for a contract for an offshore wind project. In November 2009, the Claimant submitted eleven FIT applications for wind power projects totalling 1,045 MW. Ten of its applications were for onshore wind projects totalling 745 MW, and one was for a 300 MW, 130-turbine offshore wind facility. At the time of its application, the Claimant’s offshore wind project was no more than a dream. The proponent had applied for access to some Crown land, but it had not yet been granted site access over a single hectare. Further, it had no plan on how to bring its dream to a reality – it applied to the FIT Program without having conducted a proper feasibility study. It seems that although the Claimant was no more ready than other proponents, it was more willing to gamble.

10. The Government of Ontario was not ready to process offshore wind projects either. At the time the FIT Program was launched, the regulatory framework in Ontario for approving an offshore wind project, including its development, construction, operation and decommissioning, remained incomplete. The REA process, created by the GEGEA and the REA Regulation, established the framework for the regulatory approval of offshore wind projects in Ontario. However, in contrast with the proponent-driven environmental assessment (“EA”) process, the REA process is prescriptive in nature, with clear requirements for a project proponent to satisfy. When the REA Regulation came into force on September 24, 2009, MOE had yet to finalize the regulatory requirements for offshore wind facilities. For example, while it contained technology-specific rules and requirements for onshore wind facilities, which set out precise setback distances from noise receptors, property lines and land-based transportation corridors, the REA Regulation merely stipulated that an offshore wind facility report would be required for a Class 5 offshore wind facility. It did not contain the prescriptive rules that the Claimant would be required to satisfy. As the Claimant’s representative and expert witness explained at the time, “many of the rules governing off-shore projects have yet to be written.”Footnote 3

11. The OPA considered the Claimant’s FIT applications in the early months of 2010. In its application to the FIT Program for an offshore wind facility, the Claimant selected a connection point that could easily accommodate 300 MW. Since the application met the appropriate requirements under the FIT Program, the OPA had no other choice but to offer the Claimant a FIT Contract. It notified the Claimant that it would be offered a FIT Contract for its 300 MW Wolfe Island Shoals project in April 2010, and formally offered the contract on May 4, 2010. It remains the only FIT Contract for an offshore wind project that the OPA offered.

12. At the launch of the FIT Program, the standard FIT Contract for offshore wind facilities required projects to achieve Commercial Operation four years following the contract date, and subjected them to termination if their date of Commercial Operation did not occur within 18 months of that date. From the moment it was informed by the OPA that it would be offered a FIT Contract, the Claimant had doubts about whether it could satisfy such standard conditions. The Claimant expressed its concerns as early as April 19, 2010. A four-year Milestone Date of Commercial Operation (“MCOD”) would make any proponent nervous, but particularly a proponent hoping to build Canada’s largest wind facility, and the first of its kind in the world.

13. There were many development and construction risks for the Claimant’s Project. For example, the 130 massive 3,000 metric tonne foundations that the Claimant planned to use would have created considerable challenges in terms of lakebed preparation, fabrication, storage and transportation. Further, the presence of a major international shipping lane through the proposed site strongly suggests that the Project’s layout would have to change and that some of the 130-turbines would have been dropped. There would have been a number of serious construction risks as well. In particular, seasonal construction restrictions and weather disruptions, the lack of available specialized vessels, and the time required for manufacturing the foundations, all made Commercial Operation within a four-year period likely impossible.

14. Moreover, the Claimant had an even more obvious reason to be concerned about the viability of its proposal in the spring and summer of 2010. On June 25 and August 18, 2010, MOE and MNR, respectively, had posted for public comment on the Environmental Registry, policy proposal notices regarding offshore wind and access to Crown land for offshore wind projects. In particular, MOE’s June 25, 2010 proposal notice (the “Offshore Wind Policy Proposal Notice”) explained that work on the regulatory framework for offshore wind development was ongoing, and that the requirements for offshore wind projects under the REA Regulation remained incomplete. It noted that MOE would be engaging with other ministries to make the necessary regulatory and policy changes to provide greater certainty and clarity on offshore wind requirements.

15. The Offshore Wind Policy Proposal Notice also discussed human health and environmental considerations around offshore wind development and solicited input on a proposed five kilometre shoreline exclusion zone for offshore wind projects. In particular, it highlighted the need to protect water bodies and to ensure that Ontarians enjoy safe drinking water, beaches, food and fish, as well as preserve the province’s natural and cultural heritage. The notice anticipated that the future offshore-specific guidance documents would include Cultural Heritage Guidance for Offshore Renewable Energy Projects from the Ministry of Tourism and Culture (“MTC”), Offshore Wind Noise Guidelines from MOE, and Coastal Engineering Study Guidance from MNR. The notice made clear that the proposed direction was subject to change, depending on the feedback received from the public through the Environmental Bill of Rights (“EBR”) process and research underway by MOE, MNR, and MTC.

16. It was at this juncture that the Claimant, once again, demonstrated its extraordinary risk tolerance. While MOE was still receiving feedback from the public and conducting its own research, the Claimant signed its FIT Contract on August 20, 2010. The only difference between its FIT Contract and the standard contract was that it had five years, instead of four years, to bring its Project into Commercial Operation.

17. In signing its FIT Contract, the Claimant took a number of high-risk gambles. It gambled that MOE would adopt only a five kilometre setback as a means of addressing all of the concerns raised by the public and the research. Given that 85 per cent of the Crown land that the Claimant had applied for was located within the proposed five kilometre setback, the Claimant also gambled that it would be allowed to swap its existing Crown land applications for Crown land located outside the proposed five kilometre setback. Finally, in signing its FIT Contract, the Claimant accepted the OPA’s termination rights and gambled that it would be able to bring its project into Commercial Operation within five years, despite being well aware that the regulatory process for its permits and approvals was still under development.

18. The public response to MOE’s Offshore Wind Policy Proposal Notice was unprecedented. MOE received many more comments in response than for any other EBR posting related to renewable energy, and 65 per cent of those received were opposed to offshore wind development altogether. The majority of comments considered that more scientific research was required to ensure that a five kilometre setback would be sufficient. Specific concerns for further study included measures to protect drinking water, transportation and navigation, and potential effects on fish and wildlife and shoreline ecosystems. The heightened public interest in offshore wind along with strong likelihood that a REA decision on the first project would be challenged, made it clear to MOE that its policy on offshore wind development had to be bullet-proof.

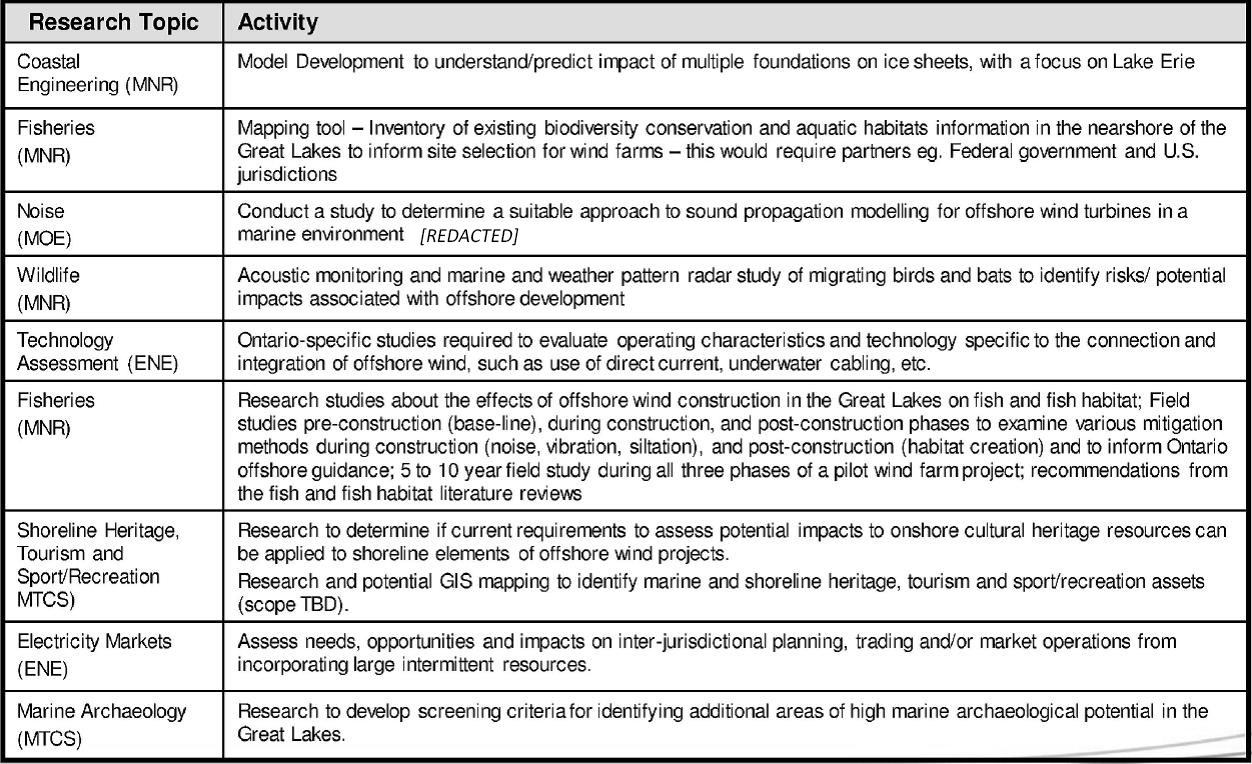

19. MOE continued its work to develop the REA policies and guidelines for offshore wind throughout the summer and fall of 2010. It conducted a review of what other jurisdictions were doing and held a number of technical workshops with both government experts and independent experts on noise, water quality, technical specifications and safety issues. This review and the discussions at those meetings made clear that further scientific work was required to understand the risks associated with offshore wind development, operation and decommissioning in the Great Lakes. As the Great Lakes Wind Collaborative (“GLWC”) later recognized, Great Lakes region-specific research on the ecological impacts of offshore wind is “notably lacking”, and “[a]dditional research and studies are needed to direct how wind projects are planned, sited and operated in the region.” Footnote 4 It forecasted the research needed to answer these questions will likely take “years and possibly decades”.Footnote 5 In line with these opinions, the Government of Ontario worked with the [REDACTED] Ontario initially envisaged a three-year plan to complete its work.

20. As a result, by January 2011, it was clear to the Minister of Environment that the scientific underpinnings for the regulations required years of research, and that any policy on offshore wind development had to be supported by sound science because it would be closely scrutinized. He therefore decided, along with his colleagues, the Ministers of Energy and Natural Resources, to defer offshore wind development altogether. Contrary to the Claimant’s baseless allegations of political interference, the Minister of the Environment’s decision was grounded in the precautionary principle. He made the decision in the discharge of his duties to protect human health and the environment.

21. The only question that remained was what to do with the Claimant’s FIT Contract and the other Crown land applications for offshore wind. Ultimately, the Government of Ontario decided to cancel all Crown land applications for offshore wind sites with the exception of the Claimant’s. Given the Claimant’s unique position as the only FIT Contract holder for offshore wind, its contract was frozen until the regulatory framework could be finalized. Upon communicating this message to the Claimant, government representatives invited it to meet with the OPA to reach a suitable arrangement, which might include changes to the FIT Contract’s Force Majeure, security deposit and termination provisions. Such meetings with the OPA occurred, but the Claimant rejected the reasonable solutions put forward to accommodate it, and instead made unreasonable and unrealistic demands of the OPA and the Government of Ontario. It was the Claimant that ultimately abandoned the discussions.

22. Ontario has not abandoned its efforts to complete the science required to move forward with offshore wind development. In fact, it is still undertaking the work required in order to allow it to develop the required regulatory framework, with additional studies being commissioned and money continuing to be spent on new science.

23. Throughout this entire time, the Government of Ontario has acted reasonably and fairly, and it has appropriately balanced all of the various interests involved. The fact is that Ontario needs more time to develop the regulatory framework for offshore wind development in the Great Lakes, a common concern of all Great Lake partners. NAFTA does not require a government to rush into decisions simply because the Claimant took unnecessary risks in choosing to sign a FIT Contract that requires Commercial Operation by a certain date. To the contrary, NAFTA Parties have maintained the regulatory space to proceed with caution and ensure that their programs and policies have an adequate scientific foundation.

24. Moreover, as the evidence in the record shows, Ontario has done everything reasonably possible to accommodate the Claimant and its project while the necessary scientific foundation for the regulation of offshore wind development is laid. To be clear, Ontario did not revoke any of the Claimant’s permits. The Claimant had none. Ontario did not impose a halt on ongoing construction. Construction had not even begun. Ontario did not cancel or invalidate the Claimant’s FIT Contract with the OPA or direct the OPA to change any of its terms. The Claimant’s FIT Contract remains in force and is binding today. Ontario did not even materially change the regulatory environment that existed when the Claimant made its investment. In fact, the status quo that existed when the Claimant invested in Ontario continues to exist today. What Ontario did do was offer the Claimant the opportunity to freeze its contract and remain protected from termination. It was the Claimant that refused.

25. It was the Claimant’s choice to assume the risks associated with the FIT Contract, and it did so with full knowledge of the development, construction and regulatory risks involved. It should not be compensated just because those risks have materialized. Indeed, contrary to its allegations, the Claimant also needed more time if it was to have any chance of successfully developing a project. However, it did not have that luxury. The Claimant’s FIT Contract contains specific termination rights in favour of the OPA, and there should be little dispute that at the time of the decisions being challenged here, the Claimant had an unviable project. Given where the Claimant was in the development process when it signed its FIT Contract, and given the first-of-a-kind nature of its proposal, the Windstream Wolfe Island Shoals offshore wind facility was doomed to fail from the moment that the Claimant signed on the dotted line. It was simply not a project that could be built within the timelines required by the FIT Contract. NAFTA Chapter 11 is not intended to provide a windfall to a Claimant merely because it had an idea.

26. In sum, the Claimant has failed to prove that any aspect of the Government of Ontario’s decision to defer offshore wind development on February 11, 2011 breached Canada’s obligations under the NAFTA or caused it any losses. Canada has structured the remainder of its submissions as follows.

27. First, Canada will provide an overview of the relevant facts related to this dispute. In particular, Canada will describe the FIT Program, the Provincial and Federal approval and permitting requirements applicable to renewable energy projects, the Claimant’s proposal and the circumstances surrounding its signing of its FIT Contract, the Government of Ontario’s decision to defer the development of offshore wind facilities, and the Government of Ontario’s efforts to do the science required to support the development of a regulatory framework for offshore wind projects.

28. Second, Canada explains that the Tribunal lacks jurisdiction to consider the legality of measures which are not measures of the Government of Ontario, but of state enterprises that were not acting in the exercise of delegated governmental authority, namely the OPA.

29. Third, Canada shows that, pursuant to Article 1108, Articles 1102 and 1103 do not apply in this dispute because the measures challenged as a breach of those articles constitute or involve procurement.

30. Fourth, Canada explains that even if the Tribunal were to consider the alleged breaches of Articles 1102 and 1103, these claims are meritless. The Claimant has failed to demonstrate that either TransCanada Corporation (“TransCanada”), Samsung, or any other comparator, was accorded more favourable treatment in like circumstances. Neither TransCanada nor Samsung were FIT proponents, and neither sought to develop an offshore wind project in Ontario. As a result, the decision to defer offshore wind development did not apply to them. In fact, the treatment accorded to the Claimant was more favourable than the treatment of investors with whom it was in like circumstances, namely other proponents of offshore wind projects in Ontario who applied for FIT Contracts. The Claimant’s Project was kept alive, but all others were cancelled.

31. Fifth, Canada shows that it has also not violated any of its obligations under Article 1105. While the Claimant has tried to tell a story of political interference and asked for an adverse inference to be drawn from unrelated events, there is no evidence that the deferral decision was politically motivated. Contrary to the Claimant’s baseless allegations, the Government of Ontario’s approach was based on the need for additional research, something that U.S. Great Lake jurisdictions equally require. In particular, it was based on the need for research to develop and support an adequately informed and scientifically defensible regulatory framework for offshore wind. Furthermore, the decision to defer offshore wind development was, itself, entirely consistent with the REA Regulation and did not violate any specific commitments made by the Government of Ontario to the Claimant. The Claimant has failed to establish that it had any legitimate expectations that its Project would be able to proceed quickly through the regulatory process before the requirements for offshore wind facilities were put in place, or that Ontario made any specific representations and assurances that induced its investments. Far from being shocking or egregious, the treatment accorded to the Claimant was reasonable and accommodating.

32. Sixth, Canada explains why the alleged measures do not violate Canada’s obligations under NAFTA Article 1110. There has been no expropriation, since the deferral has not resulted in a substantial deprivation of the Claimant’s investments. In particular, neither the Claimant’s Project nor its key asset, the FIT Contract, had economic value prior to the alleged expropriation and further, even if they did, the deferral is merely temporary in nature. The deferral is a good faith, non-discriminatory general measure adopted for the public purpose of ensuring that the Government of Ontario is in a position to adequately assess any environmental, health and safety risks associated with offshore wind energy development. It is not an unlawful expropriation.

33. Finally, Canada shows that even if this Tribunal were to find a breach of Canada’s obligations, the Claimant did not suffer any losses as a result of that breach. The Claimant could not have brought its Project into operation within the deadlines in the FIT Contract, and hence, the Project was valueless before any of the measures being challenged here were adopted by Ontario. Further, even if the Tribunal were to ignore this fact, there are numerous other factors associated with the riskiness and costs of the Claimant’s Project that would have rendered it valueless on the valuation date. This was a project that simply was not viable within the contractual constraints to which the Claimant agreed and accordingly it had no value at the time of the alleged wrongful conduct.

II. The Roles and Mandates of the Ministries of the Ontario Government and the Ontario Power Authority Relative to Renewable Energy Projects in Ontario

34. Several ministries of the Government of Ontario, and the independent OPA, are involved in the renewable energy sector in Ontario, each with a different mandate.

- The Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change, or the Ministry of the Environment (“MOE”) as it was known previously,Footnote 6 is responsible for promoting clean and safe air, land, and water to ensure healthy communities, ecological protection and sustainable development for Ontarians.Footnote 7 It is the primary regulator of renewable energy projects in Ontario, through the administration of Part V.0.1 of the Environmental Protection ActFootnote 8 and its implementing regulation, the Renewable Energy Approval Regulation.Footnote 9 When making decisions in respect of renewable energy, MOE is guided by the purpose of Part V.0.1 of the EPA which provides for the protection and conservation not only of the natural environment (i.e. air, land and water, and plant and animal life including human life), but also of the human environment, including the social, economic and cultural conditions that influence human and community life.Footnote 10 MOE also administers a number of other statutes including the Clean Water Act, 2006, the Environmental Assessment Act, the Ontario Water Resources Act, the Environmental Bill of Rights, 1993 and the Safe Drinking Water Act, 2002.Footnote 11

- The Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, or the Ministry of Natural Resources (“MNR”) as it was known previously,Footnote 12 exercises stewardship over Ontario’s provincial parks, forests, fisheries, wildlife, mineral aggregates, petroleum resources and Crown land and waters.Footnote 13 It has two main roles relating to renewable energy in Ontario. First, MNR is responsible for the management, sale and disposition of Crown land under the Public Lands Act.Footnote 14 Second, MNR is responsible for reviewing the natural heritage component (birds, bats and fish) of REA applications before they are submitted to MOE. It also administers additional permits that may be required during the development of a renewable energy project, including permits to conduct geotechnical testing of the lakebed.

- The Ministry of Energy, or the Ministry of Energy and Infrastructure (“MEI”) as it was known previously,Footnote 15 establishes energy policy and the legislative and regulatory framework in which regulated entities and electricity-sector participants must operate in order to develop the electricity generation, transmission and other energy-related facilities that help power the Ontario economy in a sustainable manner. Footnote 16 MEI is responsible for publishing the Long-Term Energy Plan,Footnote 17 which guides the policies for energy procurement and conservation in the province. MEI is responsible for the administration of the Green Energy Act,Footnote 18 which established the Renewable Energy Facilitation Office (“REFO”), a “one-window access point” where proponents of renewable energy projects can obtain information and connect with the appropriate government and agency resources.Footnote 19 Through REFO, the Ministry plays a coordinating role for specific renewable energy projects.

- The Ministry of Tourism, Culture and Sport or the Ministry of Tourism and Culture (“MTC”) as it was known previously, is responsible for reviewing the cultural heritage resources (archaeological resources and heritage resources) components of REA applications, before they are submitted to MOE.Footnote 20

- The Ontario Power Authority (“OPA”), was, prior to January 1, 2015, an independent non-share capital corporationFootnote 21 established pursuant to the Electricity Restructuring Act, 2004. On January 1, 2015, amendments to the Electricity Act, 1998 came into force to provide for the amalgamation of the OPA and the Independent Electricity System Operator (“IESO”). The new entity was continued under the IESO name.Footnote 22 The predecessor OPA was responsible for medium and long-term system planning, conservation, demand management and procurement of new generation through long-term power purchase agreements (“PPAs”).Footnote 23 It was also charged with developing integrated power system plans to manage and respond to the demand, supply and transmission goals identified by the Government of Ontario.Footnote 24 The Electricity Act, 1998 provided that the predecessor OPA was not an agent of the Crown.Footnote 25 Pursuant to 25.32 and 25.35 of the Electricity Act, 1998, the Minister of Energy has the power to issue directions to the OPA with respect to energy procurement programs. The OPA developed and the IESO continues to administer the FIT Program and is the creditworthy counterparty of FIT Contract holders.

III. Materials Submitted by Canada

35. Along with this Counter-Memorial and the attached exhibits and authorities, Canada has submitted the following documents:

- Witness Statement of John Wilkinson: Mr. Wilkinson served as Member of Provincial Parliament in the Legislative Assembly of Ontario from October 2, 2003 to September 7, 2011. During his first term, Mr. Wilkinson acted as Parliamentary Assistant to the former Minister of the Environment Leona Dombrowsky. During his second term he served in the provincial Cabinet, first as Minister of Research and Innovation, then as Minister of Revenue, and finally as Minister of the Environment from August 18, 2010 to October 20, 2011. He made the decision to defer offshore wind development in the discharge of his duties as the Minister of the Environment.

- Witness Statement of Marcia Wallace: Dr. Wallace is currently the Regional Director, Municipal Services Office – Central Ontario, at the Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing (“MMAH”) of the Government of Ontario. Prior to this, she was Manager, Renewable Energy, in MOE’s Environmental Programs Division from November 2008 to July 2010. She then became the Director, Modernization of Approvals until October 2013 when she started her position at MMAH. She navigated MOE through the design, development and implementation of the GEGEA by coordinating and leading the development of a regulatory framework for the new Renewable Energy Program. Dr. Wallace has knowledge of the regulatory framework for the approval of renewable energy projects in Ontario and is familiar with work undertaken by MOE to develop the regulatory framework for offshore wind. She participated on behalf of MOE in the multi-ministry process of developing policy options for offshore wind in the months before the deferral.

- Witness Statement of Doris Dumais: Ms. Dumais is MOE’s current Director, Modernization of Approvals, and has nearly three decades of experience in the areas of program delivery and program development for environmental permitting and approvals. She worked in MOE’s Operations Division as Director of the Approvals Program from December 2007 to September 2011, when she became Director of the new Environmental Approval Access and Service Integration Branch. Ms. Dumais led the team of technical specialists responsible for screening and reviewing applications for REAs, including the Directors who decide whether or not it is in the public interest to issue or refuse to issue a REA.

- Witness Statement of Rosalyn Lawrence: Ms. Lawrence is the Assistant Deputy Minister of the Policy Division at MNR, which is responsible for all policy development related to natural resource management matters. She has general knowledge about the issuance of MNR permits and approvals related to renewable energy, including issues related to Crown land offshore wind development, and the development of a regulatory framework for offshore wind.

- Witness Statement of Susan Lo: Ms. Susan (“Sue”) Lo was the Assistant Deputy Minister of the Renewables and Energy Efficiency Division at MEI from June 2009 until February 2013. She was involved in the implementation of the GEGEA, including the FIT Program and the establishment of REFO. Ms. Lo was further involved in the development of the Government of Ontario’s 2010 Long-Term Energy Plan (the “2010 LTEP”) and MEI’s policy discussions regarding options for moving forward with offshore wind development.

- Witness Statement of Perry Cecchini: Prior to January 1, 2015, Mr. Cecchini was Manager RESOP/FIT in the Electricity Resources Contract Management group at the OPA; on January 1, 2015, the OPA was merged with the IESO, where Mr. Cecchini retains the same functional role in the Market and Resource Development division. Mr. Cecchini was involved in the administration of FIT contracts and, along with his team, remains responsible for ensuring that FIT Contract counterparties develop and operate renewable energy generation facilities in accordance with the terms of their particular FIT Contract.

- Expert Report of URS: URS has provided an expert report assessing the environmental permitting and engineering feasibility of the Claimant’s Project. URS is a global engineering company with experience in complex and diverse engineering projects all over the globe, including renewable energy projects. URS is considered one of the world’s foremost engineering companies.

- Expert Report of Berkeley Research Group: Mr. Chris Goncalves, of Berkeley Research Group (“BRG”) has provided an expert report assessing the Claimant’s damages claim. He and his team are economics and valuation experts with experience assessing the value of renewable energy projects, and in assessing damages in international arbitration.

The Facts

I. Background on Renewable Energy Policy in Ontario

A. Ontario’s Early Renewable Energy Initiatives 2003-2008

36. In 2003, the newly elected Government of Ontario was faced with the need to restructure an electricity system that was dependent for approximately one quarter of its generation capacity on heavily polluting coal-fired power plants.Footnote 26 In light of the health and environmental concerns associated with such facilities, their elimination became one of the key priorities of the new government’s election campaign in 2003.Footnote 27 An independent study commissioned by the new government in 2005, entitled Cost Benefit Analysis: Replacing Ontario’s Coal-Fired Electricity Generation, estimated that the elimination of coal-fired generation would lead to annual savings of $4.4 billion, when health and environmental costs were taken into consideration.Footnote 28

37. The decision to eliminate coal-fired generation signalled an era of significant change in Ontario’s energy policy, with new energy initiatives, legislation and evolving regulatory frameworks being developed, adopted and implemented across multiple ministries. In order to replace, at least in part, the coal-fired electricity generation capacity that was being eliminated, the Government of Ontario sought to significantly increase electricity supply and capacity from renewable sources of energy generation, such as solar, wind, bioenergy and hydro-electric energy.

38. As a first step, in June 2004 the government introduced the Electricity Restructuring Act, 2004 (“ERA”) in the Legislative Assembly of Ontario (“Ontario Legislature”).Footnote 29 One of the purposes of the ERA was “to restructure Ontario’s electricity sector, and to promote the expansion of electricity supply and capacity, including supply and capacity from alternative and renewable energy sources.”Footnote 30 The ERA was passed by the Ontario Legislature and came into force in December 2004.Footnote 31

39. A major feature of the ERA was the establishment of the OPA through amendments to the Electricity Act, 1998.Footnote 32 The OPA was an independent non-share capital corporation responsible for medium and long-term system planning, conservation, demand management and procurement of new generation through long-term PPAs.Footnote 33 It was constituted with independent legal personality by being given the “capacity, rights, powers and privileges of a natural person for the purpose of carrying out its objects”.Footnote 34 The Electricity Act, 1998 expressly stipulates that the OPA is not an agent of the Crown.Footnote 35

40. The ERA specifically empowered the OPA “to enter into contracts relating to the procurement of electricity supply and capacity”,Footnote 36 including from alternative and renewable energy sources.Footnote 37 It also charged the OPA with developing integrated power system plans to manage and respond to the demand, supply and transmission goals identified by the Government of Ontario in supply mix directives made pursuant to the Electricity Act, 1998.Footnote 38

41. Because the OPA is an independent corporation, the Electricity Act, 1998 specifically empowers the Minister of Energy to direct the OPA to take certain specified actions with respect to its energy procurement programs. This allows, for example, the Minister of Energy to direct the OPA to take actions that relate to the government’s broader energy policy objectives. The decision of whether or not to issue a direction to the OPA is entirely within the discretion of the Minister of Energy.Footnote 39 The scope of the Minister’s authority to issue directions to the OPA is limited to the types of directions specified in sections 25.32 and 25.35 of the Electricity Act, 1998.

42. In conjunction with and following the introduction of the ERA, the Government of Ontario directed the OPA to implement a number of renewable energy procurement initiatives, including (1) the Renewable Energy Supply (“RES”) I and II procurements, which ran in 2004 and 2005 and together resulted in nineteen contracts being awarded for approximately 1,300 MW of capacity, and (2) the Renewable Energy Standard Offer Program (“RESOP”), which ran from 2006 until May 2008 and resulted in 314 contracts being awarded for approximately 1,300 MW of capacity.Footnote 40

B. The Green Energy and Green Economy Act, 2009

43. On February 23, 2009, the Government of Ontario introduced the Green Energy and Green Economy Act, 2009 (“GEGEA”) into the Ontario Legislature.Footnote 41 It was passed and received Royal Assent on May 14, 2009.Footnote 42 The GEGEA aimed to build and support a strong green economy and to better protect the environment,Footnote 43 by “making it easier to bring renewable energy projects to life” and by fostering a culture of conservation by promoting lower energy use.Footnote 44 To accomplish these aims, the GEGEA created new standalone legislation, the Green Energy Act, 2009,Footnote 45 and amended fifteen other existing statutes.

44. Among other things, the GEGEA:

- amended the Planning ActFootnote 46 to exempt certain renewable energy projects from municipal plans, bylaws and orders related to land use and zoning;Footnote 47

- established REFO within MEIFootnote 48 to act as a “one-window access point” responsible for connecting renewable energy stakeholders with the relevant government ministries and regulatory authorities;Footnote 49

- granted the Minister of Energy authority to direct the OPA to establish a feed-in tariff program designed to procure energy from renewable energy sources;Footnote 50 and

- established the REA process in order to “coordinate approvals from the Ministries of the Environment and Natural Resources into a streamlined process”.Footnote 51

II. The FIT Program

A. The Creation of the FIT Program

45. The GEGEA added section 25.35 to the Electricity Act, 1998, authorizing the Minister of Energy to direct the OPA to develop a feed-in tariff program.Footnote 52 A feed-in tariff program is a renewable energy standard offer procurement program that features standardized program rules, contract prices designed to reflect the costs of generation, and economic incentives for proponents of renewable generation.Footnote 53 Feed-in tariff programs are used worldwide to encourage and promote the greater use of renewable energy sources. In fact, in the summer of 2008, the Minister of Energy made trips to Denmark, Germany, Spain and California where he reviewed their approaches to renewable energy, including their use of feed-in tariff programs.Footnote 54

46. On September 24, 2009, the Minister of Energy exercised the authority granted to him and directed the OPA, pursuant to sections 25.35 and 25.32 of the Electricity Act, 1998, to “develop a feed-in tariff (“FIT”) program […] designed to procure energy from a wide range of renewable energy sources,” including wind, solar photovoltaic, bioenergy, and smaller-scale (50 MW or less) waterpower (together, referred to as the “Minister’s Direction”).Footnote 55 The program was publicly announced the same day.Footnote 56

47. The Minister’s Direction established the following objectives for the FIT Program:

- increase capacity of renewable energy supply to ensure adequate generation and reduce emissions;

- introduce a simpler method to procure and develop generating capacity from renewable sources of energy;

- enable new green industries through new investment and job creation; and

- provide incentives for investment in renewable energy technologies. Footnote 57

48. The Minister’s Direction further specified that FIT Contracts would take the form of 20-year PPAs for all renewable fuels except waterpower, which would have 40-year PPAs.Footnote 58 However, the Minister’s Direction emphasized that, notwithstanding the obtaining of a FIT Contract, projects would still need to obtain regulatory approval. In particular, the Minister’s Direction stated that proponents would be “subject to all laws and regulations of the Province of Ontario and Government of Canada.”Footnote 59 The concurrent press release announcing the FIT Program also noted that while the FIT Program would simplify the OPA’s contracts and pricing for new renewable energy projects, proponents still had to “navigate through the regulatory approvals [that were] necessary”.Footnote 60

B. The FIT Rules

49. On September 30, 2009, a week after receiving the direction to establish the FIT Program, the OPA released Version 1.1 of the FIT Rules.Footnote 61 The OPA had consulted the public and other stakeholders extensively during the development of the FIT Rules throughout the summer of 2009.Footnote 62

50. The FIT Rules govern all aspects of the FIT Program including eligibility, application requirements, application review and acceptance, connection availability management, the contract form and execution, contract pricing, settlement arrangements, Aboriginal and community projects, program review and amendments, confidentiality, and program launch.Footnote 63 Pursuant to the FIT Rules, to be eligible to participate in the FIT Program, an applicant had to meet only certain basic project eligibility requirements. In the case of applications for wind power projects, the only substantive requirements were that the applicant’s proposed generating facility had to:

- be located in the Province of Ontario;

- constitute a renewable generating facility, but not be an Existing Generating Facility at the time of the application (subject to exceptions for incremental projects);

- connect to a distribution system, a host facility or the IESO-controlled grid; and

- not have or have had a prior contract relating to the proposed facilityFootnote 64

51. In addition to the foregoing basic eligibility requirements, the FIT Rules also established application requirements for ensuring that a renewable energy project, including a wind project, met the program eligibility conditions. Specifically, applicants had to submit to the OPA:

- nona-refundable application fee, based on Contract Capacity, of a maximum of $5,000;Footnote 65

- application security, based on the size of the project, to a maximum of $10,000/MW;Footnote 66

- an authorization letter authorizing the local distribution company and IESO to provide the OPA information relating to the applicant or project;Footnote 67

- connection details regarding the project, including contract capacity, renewable fuel(s), proposed connection point and other information such as name of feeder, transformer station or high-voltage circuit) or an indication that it intended to be enabler requested;Footnote 68

- evidence of site access (land ownership, land lease, option agreement, etc.) or evidence of having applied for site access where the proposed project was on provincial Crown land;Footnote 69 and

- a valid email address for the purposes of correspondence related to the FIT Program.Footnote 70

52. If a project met the eligibility requirements, and filed a correct and complete application, then the application would be reviewed by the OPA and ranked in accordance with the relevant criteria specified in the FIT Rules.Footnote 71 Generally, applications were ranked based on the time that they were received by the OPA. However, at the launch of the FIT Program, all applications were treated as though they were received at the same time, and were given a ranking based on whether they met certain shovel-readiness criteria. Applications were then considered for FIT Contracts in the order of their provincial ranking.Footnote 72 Whether an application would be offered a FIT Contract depended solely upon whether there was connection capacity at the point that it had specified in its FIT Contract.Footnote 73 Accordingly, even a low-ranked project could receive an offer of a FIT Contract if there was still capacity at the point on the electricity system where it chose to connect when its application was considered by the OPA. The offer of a FIT Contract was not a guarantee that the project would proceed or that it would be commercially successful.

C. The Standard FIT Contract

53. Like the FIT Rules, the standard form FIT Contract was also released on September 24, 2009 after having been subject to public and stakeholder consultation process during the summer months.Footnote 74 The FIT Contract is a standard long-term fixed-price contract that provides standard terms and conditions applicable to all FIT projects, as well as terms and conditions specific to the different types of renewable energy fuels under the FIT Program.Footnote 75

1. Term and Pricing

54. As noted above, the Minister’s Direction mandated that PPAs entered into pursuant to the FIT Program would be 20 years in length for projects other than water power projects, which would receive a 40-year term.Footnote 76 The FIT Rules require the pricing of FIT Contracts to be set in accordance with the price schedule in force at the time of the Offer Notice.Footnote 77 The FIT Program was initially developed to offer prices with a reasonable rate of return for renewable energy.Footnote 78 For example, in 2009, when the FIT Program was launched, the specified price was 13.5 cents/kWh for onshore wind facilities, 19.0 cents/kWh for offshore wind facilities, and between 44.3 cents and 80.2 cents/kWh for solar projects.Footnote 79

2. The Milestone Date for Commercial Operation

55. FIT Contract holders (also known as “Suppliers”) are required to bring their project into Commercial Operation by the “Milestone Date for Commercial Operation” (“MCOD”) applicable under Exhibit A of their FIT Contract.Footnote 80 When entering into a FIT Contract with the OPA, a Supplier expressly acknowledges that “time is of the essence to the OPA with respect to obtaining Commercial Operation […] by the [MCOD] set out in Exhibit A”Footnote 81 and commits to bring its project into timely Commercial Operation by the MCOD. A project is deemed to have achieved Commercial Operation when the FIT Contract holder meets all the requirements as outlined in section 2.6 of the FIT Contract, including receiving a Notice to Proceed (“NTP") from the OPA.Footnote 82

56. The MCOD is defined in terms of a period of time following the Contract Date, which is the date on which the FIT Contract was awarded, as set out on the contract cover page.Footnote 83 Time frames for achieving Commercial Operation vary depending on the renewable fuel type.Footnote 84 The MCOD time periods set at the launch of the FIT Program were three years for an onshore wind facility, three years for a solar project, four years for an offshore wind facility, and five years for a waterpower facility.Footnote 85

3. Force Majeure

57. The FIT Contract allows Suppliers who encounter difficulty in meeting their obligations under the FIT Contract, including achieving their MCOD due to factors outside their control, to invoke Force Majeure. Section 10.1 of the FIT Contract, which contains the provisions on Force Majeure, provides that if an event of Force Majeure prevents the Supplier from meeting an obligation, including achieving Commercial Operation by the MCOD, the Supplier will be excused and relieved from performing or complying with such obligation during the period in which the Supplier is in Force Majeure status.Footnote 86

58. So long as the OPA is notified in a timely fashion that the Supplier is invoking Force Majeure and the Supplier provides the full particulars of the event of Force Majeure as required by Section 10.1 of the FIT Contract, Force Majeure is deemed to have been invoked with effect from the commencement of the event or circumstances constituting the Force Majeure (the “Force Majeure event”).Footnote 87 If the Force Majeure event prevents the Supplier from achieving Commercial Operation by its MCOD, the FIT Contract requires that the OPA extend the MCOD for the reasonable period of delay directly resulting from the Force Majeure event.Footnote 88

4. The OPA’s Termination Rights

(a) Supplier Default Termination

59. The Supplier accepts the risks of being unable to meet the MCOD specified in its FIT Contract. The Term of the FIT Contract expires on the day before the twentieth anniversary of the earlier of the MCOD and actual Commercial Operation date.Footnote 89 Thus, if a Supplier is unable to meet its MCOD, then it may not be able to capitalize on the full value of the FIT Contract, unless the OPA extends the Term,Footnote 90 or the Supplier does by making payment to the OPA at a rate and within the timeframe specified in the FIT Contract.Footnote 91

60. More importantly, however, under the FIT Contract, if more than 18 months have passed since the MCOD (“the Default Date”), it is considered a Supplier Event of Default unless the project is in Force Majeure status.Footnote 92 After the Default Date, the OPA may unilaterally terminate the FIT Contract without penalty, set-off amounts owed by the Supplier against outstanding monies owed by the OPA, or draw on all, or a portion of, the Completion and Performance Security.Footnote 93

(b) Force Majeure Termination

61. Pursuant to Section 10.1(g), both the OPA and the Supplier have the right to unilaterally terminate a FIT Contract if one or more events of Force Majeure delay Commercial Operation for an aggregate of more than 24 months past the original MCOD. Similarly, under Section 10.1(h), both parties have the right to unilaterally terminate the FIT Contract if one or more events of Force Majeure prevent the Supplier from complying with obligations (aside from payment obligations and the obligation to achieve MCOD) for more than an aggregate of 36 months in any 60 month period during the Term of the FIT Contract.

62. In both cases, where either party exercises its Force Majeure termination rights, the Supplier is entitled to the return of its security.Footnote 94

(c) Pre-Notice to Proceed Termination

63. One of the main requirements for a Contract Facility to be deemed to have achieved Commercial Operation under Section 2.6(a) of the FIT Contract is for the OPA to have issued a NTP under Section 2.4 of the FIT Contract. To obtain a NTP, a Supplier has to demonstrate that it fulfilled all NTP Pre-requisites, including documentation of a completed REA (or any other equivalent environmental and site plan approvals, as applicable), a Financing Plan including signed commitment letters for at least 50 per cent of expected development costs and agreement in principle to fund the entire development costs, a Domestic Content Plan, and documentation of application for and completion of all applicable Impact Assessments.Footnote 95

64. Until the OPA issues a NTP and the Supplier pays Incremental NTP Security, pursuant to Section 2.4(a), both the OPA and the Supplier have the right to terminate the agreement in their sole and absolute discretion.Footnote 96 The OPA’s and Supplier’s mutual rights of termination under Section 2.4(a) are described as “pre-NTP termination rights”.

65. If the OPA exercises its termination right under Section 2.4(a), the Supplier is entitled to request return of all Completion and Performance Security and the OPA must refund it within 20 business days.Footnote 97 In addition, the OPA would be liable to the Supplier for its Pre-Construction Development Costs incurred prior to the Termination Date, subject to an upper limit specified in Exhibit A.Footnote 98 In the case of an offshore wind project, the OPA’s liability is capped at $500,000 plus $2 per kW of the total capacity under the FIT Contract.Footnote 99 Before the OPA issues a NTP, the OPA is not liable for any costs the Supplier incurred beyond the liability cap.Footnote 100

66. If the Supplier exercises its termination right under Section 2.4(a), the Supplier is liable to the OPA for payment of liquidated damages equivalent to the amount of the Completion and Performance Security, and would forfeit its security.Footnote 101

67. On August 2, 2011, the Minister of Energy directed the OPA to offer all Suppliers under the FIT Program the opportunity to obtain a waiver of the OPA’s pre-NTP termination rights under Section 2.4(a) of the FIT Contract.Footnote 102 The purpose of offering this waiver to all Suppliers was to support manufacturing supply chain development.Footnote 103 The Claimant accepted this offer and the OPA’s pre-NTP termination rights in the FIT Contract with the Claimant were waived on August 29, 2011.Footnote 104

5. Domestic Content

68. FIT Contract holders must construct their projects in accordance with a Minimum Required Domestic Content Level, which varies based on the type of renewable energy.Footnote 105 The requirements are specified in the FIT Rules, expressed as a percentage of a project’s components that must be domestically sourced and is calculated following the Commercial Operation Date.Footnote 106

69. The FIT Contract enumerates the criteria for meeting the domestic content requirements.Footnote 107 It specifies “designated activities” for which a qualifying percentage is applied if that activity has been completed using domestic resources. The cumulative total of the qualifying percentages allocated to the contract facility must be equal to, or greater than, the minimum required Domestic Content Level.Footnote 108

D. The Steps Remaining in the Development of FIT Projects Following FIT Contract Award

70. Obtaining a FIT Contract does not guarantee or make it any more likely that a project will be permitted to proceed to development, or that it will reach Commercial Operation.Footnote 109 Numerous regulatory approvals, permits and licenses are required prior to the commencement of construction on any project. These include provincial approvals or permits (such as a REA, in the case of a wind project) as well as federal approvals and permits, various technical impact assessments, the approval of completed financing plan, and the approval of a completed Domestic Content Plan.Footnote 110 Thereafter, as part of the requirements for Commercial Operation, the Supplier must submit a Supplier’s certificate regarding Commercial Operation,Footnote 111 an independent engineers certificate regarding Commercial Operation,Footnote 112 a Metering Plan (or relevant metering information), and an as-built single line electrical drawing. A Workplace Safety and Insurance Act clearance certificate, an Ontario Energy Board (“OEB”) Generator Licence, and connection confirmation from the local distribution company are also required.Footnote 113 Some of these approvals are significant hurdles for FIT Contract holders. In fact, over half of all projects with FIT Contracts have yet to obtain NTP.Footnote 114

III. The Provincial Approval and Permitting of Renewable Energy Projects in Ontario

A. The Renewable Energy Approval (REA) Process

71. Prior to the enactment of the GEGEA, the approval process for a renewable energy project included a patchwork of environmental approvals processes under the Environmental Protection ActFootnote 115 (“EPA”), environmental assessments under the Environmental Assessment Act,Footnote 116 and local land use planning process under the Planning Act.Footnote 117By adding Part V.0.1 to the EPAFootnote 118 and making related legislative amendments, the GEGEA consolidated the majority of these processes into one streamlined process, and made MOE the primary regulator of renewable energy projects in Ontario.Footnote 119 MOE was mandated to ensure the purpose of Part V.0.1 of the EPA, which is the protection and conservation of the environment.Footnote 120

72. Pursuant to new subsection 47.3(1) of the EPA, a proponent is prohibited from constructing or operating certain renewable energy facilities, including most onshore and offshore wind facilities, “except under the authority of and in accordance with a renewable energy approval issued by the Director” through MOE.Footnote 121

73. However, the amended EPA did not specify what form the application for a renewable energy approval should take, what its contents should be, or how it should be assessed by regulators. The details of the REA process including its application requirements were to be set out in the regulations made under the EPA.Footnote 122 Indeed, the EPA provides the authority to make regulations governing the preparation and submission of REA applications, REA application eligibility requirements, and the rules, standards, and requirements applicable to renewable energy projects (from planning to construction, operation, and decommissioning or closure).Footnote 123

74. In contrast with the iterative, proponent-driven EA process, the REA process was designed to be prescriptive. The regulator would decide in advance what criteria proponents had to fulfil. It would communicate those requirements through “clear, up-front provincial rules”,Footnote 124 and evaluate a proponent’s application against the standards specified in those rules.Footnote 125

75. To allow time to develop these regulations, the GEGEA provided that the REA-related amendments would not come into force until a date to later be proclaimed.Footnote 126 Following the enactment of the GEGEA, MOE, led by the Manager of Renewable Energy, Dr. Marcia Wallace, was responsible for leading the development of the implementing regulations.Footnote 127

1. The Development and Establishment of the REA Regulation

76. On June 9, 2009, MOE posted a proposal for public comment on Ontario’s Environmental Registry (the “REA Regulation Proposal Notice”),Footnote 128 including a document outlining in detail the proposed regulatory requirements for the REA Regulation (the “Proposed REA Regulation Content”).Footnote 129 On September 24, 2009, after the required comment period closed, the government adopted the regulation, Renewable Energy Approvals under Part V.0.1 of the Act, O. Reg. 359/09Footnote 130 (the “REA Regulation”), and Part V.0.1 of the EPA came into force.Footnote 131 The same day, MOE posted a decision notice on the Environmental Registry in respect of the regulation (the “REA Regulation Decision Notice”).Footnote 132 The REA Regulation Decision Notice informed the public of the establishment of the REA Regulation, summarized its main requirements, and also summarized the results of the public consultation and how the public consultation was taken into account in the development of the regulation.

77. According to the press backgrounder released by MEI on September 24, 2009, the REA Regulation was “designed to ensure that renewable energy projects are developed in a way that is protective of human health, the environment, and Ontario’s cultural and natural heritage.”Footnote 133 It represented a new approach to regulating renewable energy generation facilities that “integrate[d] provincial review of the environmental issues and concerns that were previously addressed through the local land use planning process (e.g. zoning or site planning), the environmental assessment process and the environmental approvals process (e.g. Certificates of Approval, Permits to Take Water).”Footnote 134

2. The Approvals Process under the REA Regulation

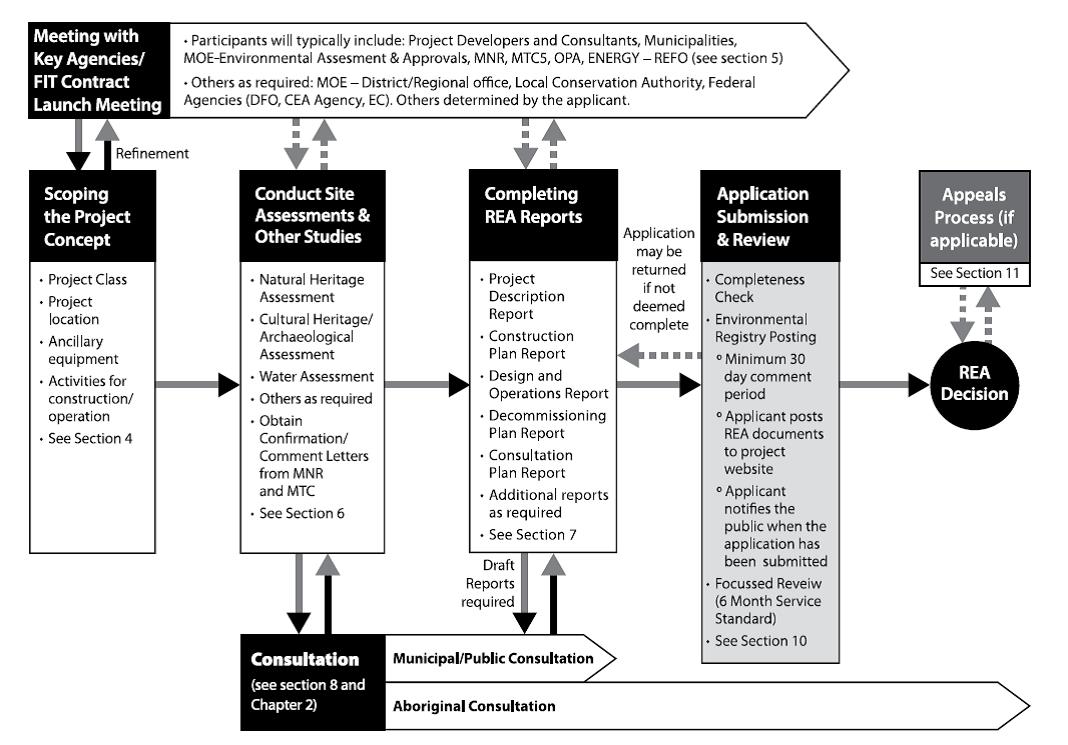

78. The following diagram summarizes the overall REA process. The various steps reflected in this diagram are discussed at length below.

Figure 1: Overview of the principal elements of the REA application process.Footnote 135

(a) REA Requirements

79. The REA Regulationprescribes technology-specific requirements for different types of renewable energy generation facilities depending on the renewable energy source that the facility uses to generate electricity.Footnote 136 The REA Regulation further divides most of the types of renewable energy generation facilities into classes and applies customized requirements to each class.Footnote 137 There are five classes of wind facilities-four for onshore (Classes 1-4) and one for offshore (Class 5).Footnote 138 If one or more parts of a wind turbine are located in direct contact with surface water other than a wetland, the facility falls into Class 5 (offshore).Footnote 139 In addition to certain technology-specific requirements applicants for Class 5 facilities must submit with their REA application an offshore wind facility report. As Dr. Wallace explains, the requirements for the report were intentionally left “broad, non-specific and descriptive” because MOE “had not yet established prescriptive technology-specific rules and requirements by the time the REA Regulation was adopted.”Footnote 140 The offshore wind facility report served as a “placeholder” for the technology-specific requirements for offshore wind that MOE would develop over time based on research and consultation, and adopt through regulatory amendments, policies and guidelines.Footnote 141

(b) REA Exemptions

80. The REA Regulation exempts certain classes of renewable energy projects from having to obtain a REA. For example, Class 1 wind facilities, which have minimal capacity of less than 3 kW (enough to power a home dishwasher and refrigerator) are exempted.Footnote 142 In addition, while Class 2 wind facilities, known as “small-scale wind” due to their lower capacity of less than 50 kW (enough to support less than 40 households or supplement a small Commercial Operation), must obtain a REA, they are subject to less onerous requirements than onshore wind facilities with higher capacity (Classes 3 and 4).Footnote 143

81. The REA process also does not apply to waterpower projects. As explained by Dr. Wallace, the REA Regulation specifically exempts all waterpower facilities from the requirement to obtain a REA, and waterpower projects remain subject to the EA and environmental approvals processes that applied before the coming into force of the GEGEA.Footnote 144 Waterpower projects were excluded from the REA requirement due to their unique engineering and site-specific design, and because they were already regulated through a streamlined approval system through the Class EA for Waterpower Projects put in place just prior to the establishment of the REA Regulation.Footnote 145 Establishing the Class EA for Waterpower Projects had taken approximately three years and involved extensive consultation and approval by Cabinet.Footnote 146 Additionally, the provincial Class EA was coordinated with the federal EA process pursuant to a federal-provincial agreement,Footnote 147 and subjecting waterpower projects to the REA process would have negated the benefits of this coordinated approach.Footnote 148

(c) Pre-Submission Activities

(i) Pre-Submission Consultation Meeting and the Draft Project Description Report

82. The process of obtaining a REA typically begins with a pre-submission consultation meeting with the Environmental Approvals Access and Service Integration Branch (“EAASIB”) of MOE.Footnote 149 The pre-submission consultation meeting is recommended, but not mandatory.Footnote 150 Regardless of whether the proponent schedules this pre-submission consultation, it must submit to MOE a draft project description report (“PDR”) and request from MOE a list of Aboriginal communities with which the proponent must consult (the “Aboriginal consultation list”).Footnote 151

83. The PDR is the central summary document in the REA application process, and is critical to MOE review and public consultation.Footnote 152 It includes a brief description of the renewable energy project and all negative environmental effects that may result from it.Footnote 153 Submission of the draft PDR is the first prescribed step in the REA application process, and is required to provide MOE with all the necessary details about facility components and proposed activities (i.e. construction, operation, decommissioning).Footnote 154 One of the key elements defined in the draft PDR is the project location, which is needed in order to proceed with the required assessments.Footnote 155

84. The Claimant never requested a pre-submission consultation meeting from the EAASIB.Footnote 156 It met with MOE representatives on multiple occasions beginning on April 19, 2010, but this was to discuss Ontario’s policy on offshore wind in general, as opposed to discussing the Claimant’s specific Project.Footnote 157 Nor did the Claimant ever submit a draft PDR or request an Aboriginal consultation list.Footnote 158 As such, it never initiated the process of applying for a REA.

85. The Claimant’s approach to advancing its project contrasts with that of other proponents of offshore wind projects, such as Trillium Wind Power Corporation (“Trillium”), which did not apply for a FIT Contract, and SouthPoint Wind, which applied for three FIT Contracts.Footnote 159 By the spring of 2010, both had initiated the REA process with MOE by submitting a draft PDR.Footnote 160 In addition, Trillium had requested an Aboriginal consultation list.Footnote 161

86. The pre-submission requirements to the REA application process include consulting with Aboriginal communities, municipalities and the public about the project, conducting the prescribed studies and assessments, obtaining comments and confirmations necessary from MTC and MNR on heritage and natural heritage requirements, and preparing the technical reports prescribed in Table 1 of the REA Regulation.

87. Table 1 of the REA Regulation sets out five “core reports” that must be submitted as part of a REA application: (1) a PDR, (2) a consultation report, (3) a construction plan report, (4) a design and operations report and (5) a decommissioning report.Footnote 162 Proponents must also provide the documentation submitted to MNR and MTC, along with any comments received. In addition, Table 1 specifies the reports required for specific types of renewable energy facilities. In the case of an offshore wind facility, this includes an offshore wind facility report.Footnote 163

(ii) The REA’s Consultation Requirements

88. The REA Regulation requires applicants to consult with Aboriginal communities, municipalities and the general public.Footnote 164 The requirements exist to ensure that stakeholders are notified about projects and provided an opportunity to give feedback and information to the applicant.Footnote 165 Consultation is a critical component of the REA process, and an application will not be deemed complete until the applicant has met or exceeded all consultation requirements.Footnote 166

89. MOE must and does take Aboriginal consultation requirements very seriously, due to the Crown’s constitutional duty to consult.Footnote 167 While the Crown is ultimately responsible for ensuring that the duty has been met, it has delegated certain procedural aspects of consultation to REA applicants through the EPA and REA Regulation.Footnote 168

90. Aboriginal consultation begins when the proponent requests an Aboriginal consultation list from MOE. This list identifies Aboriginal communities that the proponent must consult because they have constitutionally protected Aboriginal or treaty rights, or because they may be adversely affected by the project or may be interested in any negative environmental effects of the project.Footnote 169 MOE develops this list in collaboration with other ministries of the Government of Ontario, based on the proponent’s draft PDR.Footnote 170

91. Aboriginal consultation prescribed in the REA regulation involves providing communities on the Aboriginal consultation list with initial notice of the project, a draft PDR at least 30 days in advance of the first public meeting, and information on potential adverse impacts that the project may have on constitutionally protected Aboriginal or treaty rights. It also requires seeking and incorporating comments on most draft REA application documents, and providing drafts of most of the REA application documents at least 60 days in advance of the final public meeting.Footnote 171 In addition, the REA Regulation gives the Director the discretion to require additional Aboriginal consultations where the proposed project has the potential to have a significant adverse impact on the exercise of Aboriginal rights.Footnote 172 This would likely include applications for “large scale wind facilities that are expected to have significant environmental impacts, and are proposed to be located on Crown land where one or more Aboriginal communities are known to exercise an Aboriginal or treaty right.”Footnote 173

92. In addition to Aboriginal communities, a REA applicant must consult the public in general.Footnote 174 The overall public consultation process usually begins when the applicant publishes in a local newspaper a Notice of Proposal to Engage in a Project, which includes a brief description of the project proposal including a map of the project location as well as contact information of the applicant.Footnote 175 The proponent must also hold at least two public meetings, giving at least 30 days’ notice before the first public meeting and 60 days’ notice before the last public meeting.Footnote 176

93. REA applicants must also consult with the municipalities and local authorities of the area in which the proposed project is situated.Footnote 177 Municipal consultation involves providing initial notice of the project, providing a draft PDR and municipal consultation form at least 30 days in advance of the first public meeting, and providing drafts of most of the REA application documents at least 90 days in advance of the final public meeting.Footnote 178

94. Once it has completed the consultation requirements, the proponent must prepare a consultation report to include in its REA application. The report provides a record of comments and information received through the consultation process, and how they were considered, including whether the project was modified as a result.Footnote 179 It allows MOE to determine if the proponent has met the consultation requirements for a complete application.

95. The following diagram summarizes the consultation requirements of the REA process:

Figure 2: Overview of consultation requirements in the REA application.Footnote 180

(iii) The REA’s Cultural Heritage and Natural Heritage Requirements

96. In preparing a REA application, proponents must determine and address the potential negative effects of the project on cultural heritage resources and natural heritage resources at and near the project site. Ontario’s cultural heritage resources include archaeological resources, built heritage resources and cultural heritage landscapes.Footnote 181 A REA applicant must conduct both an archaeology assessment and a heritage assessment unless it determines that there is low potential for archaeological resources and heritage resources at the project location.Footnote 182

97. Archaeological resources are defined as archaeological sites or marine archaeological sites.Footnote 183 An archaeological site is “any property that contains an artifact or any other physical evidence of past human use or activity that is of cultural heritage value or interest”.Footnote 184 A marine archaeological site is “an archaeological site that is fully or partially submerged or that lies below or partially below the high-water mark of any body of water”.Footnote 185