Characteristics of SME exporters in Canada

January 2024

Kevin Jiang and Julia Sekkel

Key findings

- Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) make a substantial contribution to the Canadian economy but historically their involvement in cross-border trade has been relatively limited.

- Recent data, however, shows a sizable increase in their export participation, in part facilitated by the adoption of digital platforms. The percentage of SMEs that exported (export propensity) increased from 10.4% in 2011 to 12.1% in 2020. Although the most significant growth occurred between 2011 and 2014, export propensity continued to increase by 0.4 percentage points from 2017 to 2020 despite pandemic challenges.

- Over the last decade, SMEs’ share of export sales in total sales (export intensity) increased from 3.5% to 5.0%. For SMEs that export, their export intensity increased from 33% to 40%, with significant growth since 2017.

- Larger SMEs are more likely to export but the overall increase in SMEs’ export propensity since 2011 was mainly driven by the addition of new exporters in the smallest SME size group (SMEs with 1-4 employees).

- Selling services has become more prevalent among SME exporters over the last decade. In 2020, 62.4% of SME exporters exported services compared to only 51.1% in 2011. Meanwhile, the share of SME exporters that export goods declined from 60.9% to 55.3%.

- The strongest performing industries for SME exporters are manufacturing, wholesale trade, transportation and warehousing, and professional, scientific and technical services, which posted growth in both export propensity and intensity over the last decade.

- The U.S. is still by far the most important destination for SME exporters, but its significance has decreased and more SMEs are diversifying their sales to other markets.

- SME exporters are more likely to engage in importing goods and services as inputs for producing goods in Canada compared to non-exporters.

Introduction

Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) comprise the majority of Canadian companies and make a substantial contribution to the economy. As of December 2021, there were about 1.2 million SMEs in Canada, representing 99.8 percent of all employer businesses (ISED, 2022). SMEs were responsible for 88.2% of all private sector jobs in 2021 and accounted for about 53.2% of GDP on average between 2015 and 2019. The importance of SMEs to the overall economy is not particular to Canada. Across Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) economies, SMEs account for over 99% of firms and 60% of business sector employment and the majority of value-added (OECD, 2023).

SMEs' significant participation in the overall economy is not proportionately reflected in cross-border trade. In 2020, 12.1% of SMEs exported goods and services outside of Canada, which is estimated to represent about 95,400 exporting SMEs. Moreover, there exists heterogeneity among SMEs across industries and enterprises. Even within the industrial sector, the percentage of SMEs involved in exporting falls significantly short of the corresponding percentage seen in large companies. This relatively low participation of SMEs in international trade is also observed among other OECD economies. Across the majority of OECD economies, over 90% of large industrial firms engage in exporting, whereas only 10% to 25% of SMEs do so. For Canada, nearly half of large firms export in the industrial sector, compared to less than 30% for SMEs (OECD, 2018).

Selling abroad is difficult and can come with increased risks. In 2020, 86.7% of SMEs that did not export reported the “local nature of the business” as the main reason for not exporting. There are various barriers associated with international activities represented by fixed costs, including non-tariff measures and institutional barriers, as well as variable costs such as duties and tariffs. While trade agreements can be effective in reducing tariffs, some costs associated with non-tariff barriers, such as compliance with product standards and regulations, transportation costs, establishing distribution networks, and advertising are more difficult to remove and potentially affect smaller firms disproportionately (OECD, 2018). Access to information on international markets and knowledge about potential costumers can also represent barriers to firms willing to export. In Canada, the Trade Commissioner Service (TCS) provides services to address some of the non-tariff barriers through financial support and trade promotion activities for Canadian firms, including SMEs.

Various empirical findings (Bernard et al., 1995; Bernard et al., 2007; Melitz, 2013) and the seminal work from Melitz (2003) show that only firms that reach a certain level of productivity are able to bare the costs of selling in a foreign market. Smaller enterprises are generally less productive and therefore, less likely to export. Even though the size of SMEs may suggest a lower likelihood of engaging in export activities, it is important to recognize the inherent diversity among these firms. Size, in isolation, does not definitively determine a firm's export potential. Leung et al. (2008) conducted an analysis using Canadian firm-level data and confirmed that, on average, smaller firms exhibit lower levels of productivity compared to their larger counterparts, even after adjusting for industry differences. However, the study also unveiled a substantial number of smaller firms that surpass larger ones in productivity within the same industries. This underscores not only the considerable heterogeneity existing among firms but also the acknowledgment that size alone does not exclusively account for productivity disparities among them. This heterogeneity extends to Canadian exporters as well. Lilleva and Trefler (2010) identified a notable presence of smaller and less-productive firms involved in export activities, coining the term the "paradox of unproductive exporters" to describe this phenomenon. While evidence shows that firms generally need to be more productive in order to export, studies also find that there are positive spillovers from participating in global markets. Having access to larger consumer markets, being exposed to best practices abroad, and benefiting from technology transfer and learning opportunities while participating in exports can all further contribute to enhanced productivity and innovation (Alvarez et al., 2005; Baldwin & Gu, 2013; Ciuriak, 2013; Crespi et al., 2008; Melitz & Trefler, 2012). Another benefit of trade is that diversification of sales markets may boost companies’ resilience by helping them prepare, cope, and recover from shocks (WTO, 2021).

In summary, the internationalization of SMEs can contribute to increased productivity and innovation and ensure that the benefits of trade flow broadly through society. From that perspective, analyzing the patterns and main characteristics of SME exporters as well as understanding the differences among them are extremely valuable to guide policymakers on how SMEs can take advantage of exports and increase participation in international markets. Moreover, analyzing developments over time helps policymakers adapt and enhance their ability to serve Canadian firms.

Source of data and definitions

This report relies on two main sources of data. The first source is the Survey on Financing and Growth of Small and Medium Enterprises (SFG, henceforth). Led by Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada (ISED) and conducted by Statistics Canada every three years, the latest SFG has information for the full year 2020 and was released in 2022. This survey contains a representative sample of 790,000 SMEs in Canada covering most industries.Footnote 1 A valuable feature of that survey is that it covers SMEs that export both goods and services, which is important for the analysis of SMEs that export. The other source of data is the Trade in Goods by Exporter Characteristics (TEC) which covers the universe of all Canadian exporters of goods on an annual basis and is useful to complement the SFG with updated figures.

The SFG defines SMEs as companies having between 1 and 499 employees and, additionally, includes enterprises with annual gross revenue of $30,000 or more in its definition. Firms are sub-classified as small enterprises when the number of employees lies between 1 and 99 employees, and medium enterprises, with 100 to 499 employees. In contrast, companies with no employees are included as SMEs in the TEC. The TEC dataset also includes large companies for comparison, which are those with 500 employees or more.

Throughout this report, two important dimensions of export statistics are used:

- export propensity refers to the percentage of firms that export in a given group, or the likelihood of a firm being an exporter.

- export intensity represents the percentage of export sales (by value) in total sales, or the extent to which a firm export.

Additionally, the terms enterprises and firms are used interchangeably, but refer to the definition of enterprise, which includes corporations, quasi-corporations, institutions, or unincorporated businesses such as sole proprietors or partnerships.

Profile of exporting SMEs

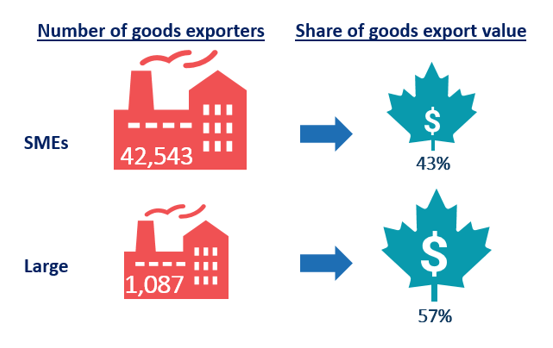

Although SMEs represent 98% of goods exporters in Canada, they contribute to less than half of the country's total goods export value, as illustrated in Figure 1. In 2020, SMEs accounted for approximately 42,500 goods exporters, large enterprises numbered nearly 1,100. However, in terms of the value of goods exports, large firms outpaced SMEs, exporting a total of $269 billion in 2020 compared to the combined export value of almost $203 billion by SMEs.

Figure 1. SME share of goods exporters and export value, 2020

Text version – Figure 1

| Number of goods exporters | Share of goods export value | |

|---|---|---|

| SMEs | 42,543 | 43% |

| Large | 1,087 | 57% |

Source: Statistics Canada, TEC. Calculations by the Office of the Chief Economist.

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020, along with the subsequent containment measures, left an indelible mark on the global economy and international trade. Canadian exports and businesses were not exempt from these far-reaching effects. Among those most significantly affected were Canadian companies, particularly SMEs, many of which were compelled to either halt their export activities or adapt their business operations. A comprehensive survey conducted in 2020 to assess business conditions revealed the extent of the turmoil. Half of all businesses reported a decline in their revenues exceeding 20%, while two-thirds of businesses found themselves severely impacted by dwindling demand (Statistics Canada, 2020). In this report, we will look back and see how Canadian SMEs, especially those that engage in international operations, evolved since 2011.

The body of this paper is divided into six parts:

- part A includes the evolution of exporting SMEs over time, both in number of exporters as well as in average export sales

- part B shows how exporter characteristics vary across different firm sizes

- part C analyzes exports by type (goods/services)

- part D covers the industrial composition of exporting SMEs

- part E presents SMEs’ export participation across countries and regions of destination

- part F takes account of SME imports and other types of international activities

A. SMEs’ participation in trade remains low but has been growing

SMEs play a vital role in bolstering the Canadian economy. When examining their performance, exporting firms stand out in several key aspects. Exporters demonstrate greater productivity, enjoy higher revenue streams, allocate more resources to research and development, and offer more competitive wages (Baldwin & Gu, 2003; Lileeva & Trefler, 2010; Mayer & Ottaviano, 2008; Melitz, 2003). Additionally, SMEs that engage in exporting exhibit distinct characteristics, such as being larger and having owners with higher levels of education and extensive experience, setting them apart from their non-exporting counterparts. Yet, the participation of Canadian SMEs in the export market is fairly low. In 2020, only 12.1% of SMEs in Canada exported goods or services. However, this number has increased from 10.4% in 2011 (Figure 2). It is worth noting that most of the growth in export propensity occurred between 2011 and 2014, where export propensity increased by 1.4 percentage points.

Export intensity, or the average share of exports in total sales, is also not high among SMEs. Considering all SMEs, an average of 5.0% of their sales were from exports of goods and services in 2020. Nonetheless, despite pandemic challenges, that share has also increased relative to 2011 and 2017, when export intensity was at 3.5% and 4.3%, respectively.

Figure 2. SME export propensity and intensity, 2011 – 2020 (%)

Text version – Figure 2

| Year | Propensity | Intensity |

|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 10.4 | 3.5 |

| 2014 | 11.8 | |

| 2017 | 11.7 | 4.3 |

| 2020 | 12.1 | 5 |

* Export intensity figure not available in 2014

Source: Statistics Canada, SFG, 2011, 2014, 2017, 2020. Calculations by the Office of the Chief Economist.

Box 1: SME exporters are active in every region in Canada

Canada boasted approximately 95,400 exporting SMEs in 2020. These exporters were not confined to a single region but rather distributed across the country. However, a notable concentration of these SMEs could be found in Ontario, British Columbia and Territories, and Quebec, which together accounted for over 80% of all SME exporters in Canada. It is also worth noting that there was some variability in the export propensity of SMEs in each region. In particular, Ontario and British Columbia and Territories shared the top spot with a 14.6% export propensity, while Alberta recorded the lowest figure at 7.2% (Table 1).

Table 1: Number of SME exporters and export propensity by region, 2020

| Number of SME exporters | Export propensity (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Canada | 95,431 | 12.1 |

| Ontario | 43,664 | 14.6 |

| British Columbia and Territories | 18,838 | 14.6 |

| Quebec | 15,943 | 9.7 |

| Alberta | 7,389 | 7.2 |

| Atlantic | 3,844 | 8.4 |

| Manitoba | 3,178 | 14.2 |

| Saskatchewan | 2,724 | 10.7 |

Source: Statistics Canada, SFG, 2020. Calculations by the Office of the Chief Economist.

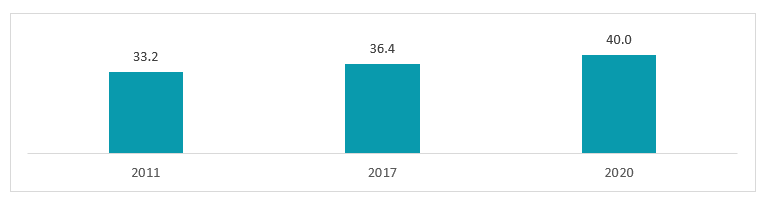

Among SME exporters, export sales represent a much larger portion of overall sales–40% on average in 2020 (Figure 3). The remaining 60% were sales realized domestically. While SME exporters do not seem to rely on international markets as their main sales destination, there has been a notable increase in export intensity since 2011 – and this continued into 2020, despite the impacts of the pandemic.

Figure 3. SME exporters’ share of sales outside of Canada (%)

Text version – Figure 3

| Year | Share |

|---|---|

| 2011 | 33.2 |

| 2017 | 36.4 |

| 2020 | 40 |

Source: Statistics Canada, SFG, 2011, 2017, 2020. Calculations by the Office of the Chief Economist.

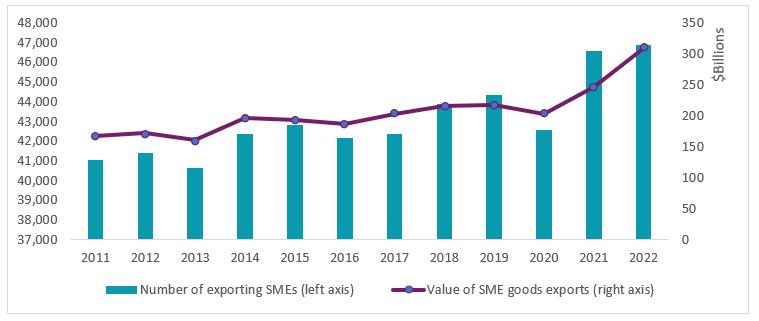

Box 2. SME goods exporters have recovered from the COVID-19 pandemic

Canadian SMEs were hit hard during the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic in the spring of 2020, with substantial declines in both goods export value and the number of goods exporters. However, starting in May 2020, both export value and the number of exporters started to recover at a fast pace, and the rebound continued throughout most of the year. By the end of 2020, the overall export value had almost fully recovered, but the number of exporters–especially SME exporters–remained well below pre-pandemic levels (Tran (2021)). For the full year 2020, SMEs’ overall goods export value fell by 6.3% and number of exporting SMEs declined 4.0% when compared to the year prior.

2021 saw a complete rebound as both the number of exporting SMEs and their value of goods exports improved significantly and reached new record highs. By the end of 2022, the number of exporting SMEs increased by 5.7% and value of goods exports were up by nearly 43% when compared to the pre-pandemic levels in 2019.

Figure 4. Number of goods exporters and value of goods exports, 2011 - 2022

Text version – Figure 4

| Value of SME goods exports | Number of exporting SMEs | |

|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 167,124,921,000 | 41,026 |

| 2012 | 171,093,468,000 | 41,372 |

| 2013 | 159,744,816,000 | 40,617 |

| 2014 | 195,595,026,000 | 42,368 |

| 2015 | 192,338,059,000 | 42,779 |

| 2016 | 186,240,634,000 | 42,160 |

| 2017 | 202,549,931,000 | 42,351 |

| 2018 | 214,810,710,000 | 43,879 |

| 2019 | 216,359,161,000 | 44,315 |

| 2020 | 202,782,860,000 | 42,543 |

| 2021 | 245,760,730,000 | 46,565 |

| 2022 | 308,995,819,000 | 46,840 |

Source: Statistics Canada, TEC. Calculations by the Office of the Chief Economist.

B. Micro-enterprises drove the increased trade participation for SMEs

Micro enterprises (SMEs with 1-4 employees) constitute the largest size group among SMEs in Canada, comprising 56.2% of the total in 2020. This figure reflects a notable increase of 3.2 percentage points since 2011. These micro enterprises also play a substantial role in the export landscape, representing almost half (49.7%) of all SME exporters, marking a significant 10.6-percentage-point increase from 2011. As previously noted, there is a strong relationship between firm size and propensity to export. Thus, it is no surprise that micro enterprises have lower export propensity and are underrepresented among exporters compared to their overall distribution within SMEs. There has, however, been a notable increase in the export propensity for micro enterprises which has driven a significant increase in their share of exporters.

Figure 5 confirms that the proportion of SMEs that export goods and services is larger among SMEs with more employees. The medium-sized enterprise group (SMEs with 100-499 employees) has the highest export propensity by far, with 36.1% engaging in exports in 2020. This group is also more than 19 percentage points more likely to export than the next largest group of SMEs with 20 to 99 employees. As discussed previously, smaller enterprises have generally less resources and are less likely to overcome export barriers. While the three larger size groups have seen some variation in their export propensity over the years, no clear trend is observed. As there are fewer SMEs in these groups, year-to-year variations occur as economic conditions change in Canada, abroad and by sector.

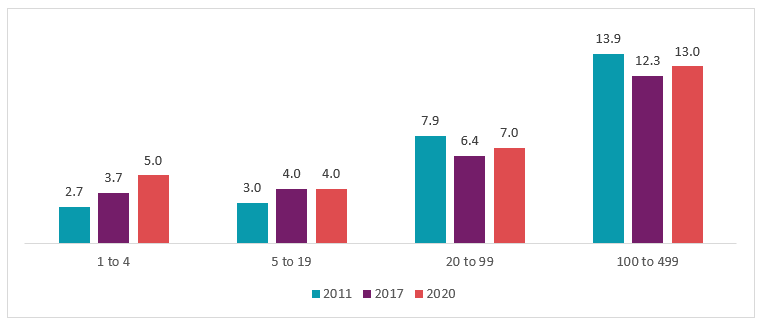

A similar trend is observed for SMEs’ export intensity across size groups; medium-sized enterprises have an average share of export sales roughly twice as large as smaller enterprises (Figure 6).

Figure 5. Export propensity –SME exporters by employment size, 2011 – 2020 (%)

Text version – Figure 5

| 2011 | 2014 | 2017 | 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 to 4 | 7.7 | 9.1 | 9.9 | 10.7 |

| 5 to 19 | 11.2 | 12.4 | 12 | 11.7 |

| 20 to 99 | 19.2 | 20.7 | 17 | 17 |

| 100 to 499 | 34.4 | 28 | 29.1 | 36.1 |

Source: Statistics Canada, SFG, 2011, 2014, 2017, 2020. Calculations by the Office of the Chief Economist.

Figure 6. Export intensity – share of exports sales of SMEs’ total sales, 2011 – 2020 (%)

Text version – Figure 6

| 2011 | 2017 | 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 to 4 | 2.7 | 3.7 | 5 |

| 5 to 19 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| 20 to 99 | 7.9 | 6.4 | 7 |

| 100 to 499 | 13.9 | 12.3 | 13 |

| All SMEs | 3.5 | 4.3 | 5 |

* Export intensity figure not available in 2014

Source: Statistics Canada, SFG, 2011, 2017, 2020. Calculations by the Office of the Chief Economist.

While smaller firm size groups have a lower tendency to export overall, the surge in SMEs' engagement in international trade since 2011 has been predominantly propelled by the expansion of exporters within the micro-enterprise category, primarily owing to its substantial numerical base. This segment has consistently registered annual growth, in contrast to other size categories, which have seen marginal growth or even declines.

In the last three years, however, the export propensity for the medium-sized enterprise group gained 7 percentage points. Furthermore, micro-enterprises gained importance not only in its proportion of exporters, but also in its share of export value, showing an increase in export intensity from 2011 to 2020.

Interestingly, both SMEs with 20 to 99 employees and medium-sized enterprises experienced a decline in export intensity from 2011 to 2017, followed by a rebound from 2017 to 2020. Collectively, these three groups contributed to a 0.7 percentage point increase in the overall export intensity observed from 2017 to 2020.

C. Services played a big role in helping SMEs export

The increased participation in trade for SMEs since 2011 was also driven by sales of services becoming more prevalent for exporters. In 2020, 62.4% of SME exporters sold services (44.7% sold services only and another 17.7% sold both goods and services) compared to 51.1% of SME exporters selling services in 2011. Meanwhile, SME exporters selling goods declined from 60.9% in 2011 to 55.3% in 2020 (Figure 7).

Figure 7. SME exporters by type of export, 2011 – 2020 (%)

Text version – Figure 7

| Goods only | Goods and services | Services only | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 48.9 | 12 | 39.1 |

| 2017 | 40.7 | 12.4 | 46.9 |

| 2020 | 37.6 | 17.7 | 44.7 |

Source: Statistics Canada, SFG, 2011, 2017, 2020. Calculations by the Office of the Chief Economist.

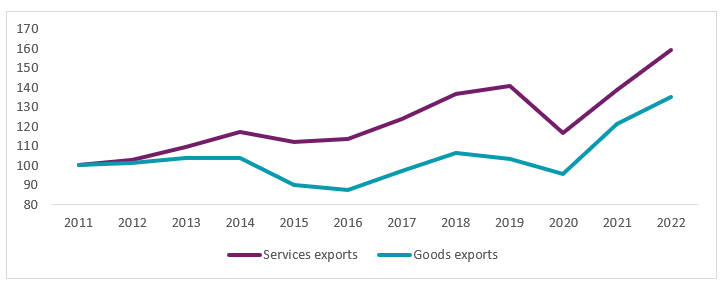

This result somewhat reflects the general composition of the population of SME exporters in Canada, where about 70% of them belong to service-producing industries (discussed in the next section). Looking at the global trend, services exports have grown in importance worldwide, increasing faster than goods exports since 2011, and SMEs in Canada also seem to be participating in that growth (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Growth in global goods and services exports, 2011 – 2022 (index: 2011 = 100)

Text version – Figure 8

| 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Services exports | 100 | 102.88818 | 109.18257 | 117.15703 | 111.9558 | 113.6601 | 123.8368 | 136.511 | 140.7948 | 116.5731 | 138.4598 | 158.9085 |

| Goods exports | 100 | 101.33725 | 103.57661 | 103.66219 | 90.13108 | 87.43524 | 97.06973 | 106.3031 | 103.1599 | 95.43067 | 121.1526 | 134.8524 |

Source: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). Calculations by the Office of the Chief Economist.

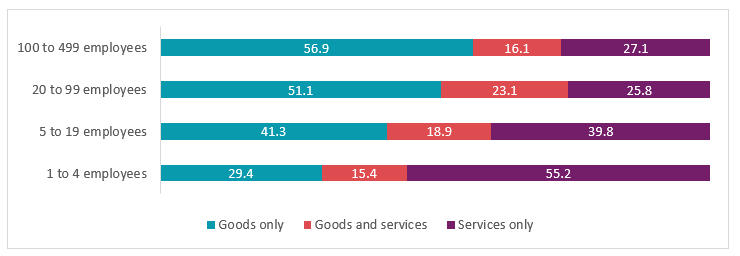

An interesting trend emerges when looking at SME exporters by number of employees and type of export. Figure 9 shows that among the four SME size groups, larger SMEs are more likely to export goods only, while smaller ones tend to export services only. In fact, micro-enterprises, the smallest group of SME exporters, are more than twice as likely to export services than the largest group. Businesses in the service-producing sector tend to be smaller than those in goods-producing sectors, for which economies of scale are more prevalent.

Figure 9. Share of SME exporters by type of export and employment size, 2020 (%)

Text version – Figure 9

| Goods only | Goods and services | Services only | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 to 4 employees | 29.4 | 15.4 | 55.2 |

| 5 to 19 employees | 41.3 | 18.9 | 39.8 |

| 20 to 99 employees | 51.1 | 23.1 | 25.8 |

| 100 to 499 employees | 56.9 | 16.1 | 27.1 |

Source: Statistics Canada, SFG, 2020. Calculations by the Office of the Chief Economist.

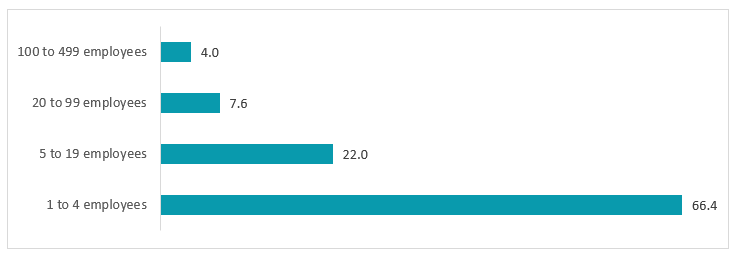

Looking at the past 10 years, the shift from exporting goods to services was also mainly supported by the smallest SME size group. Overall, the number SME exporters selling services increased by nearly 30 thousand since 2011. Micro-enterprises contributed to roughly two-thirds of the growth or 20 thousand net new exporters, followed by the 5 to 19 size group with 22.0% contribution. The two larger size groups together only contributed the remaining 11.6% (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Contribution to growth in SME services exporters by enterprise size, 2011 – 2020 (%)

Text version – Figure 10

| Contribution to growth in services exporters | |

|---|---|

| 1 to 4 employees | 66.4 |

| 5 to 19 employees | 22.0 |

| 20 to 99 employees | 7.6 |

| 100 to 499 employees | 4.0 |

Source: Statistics Canada, SFG, 2011 & 2020. Calculations by the Office of the Chief Economist.

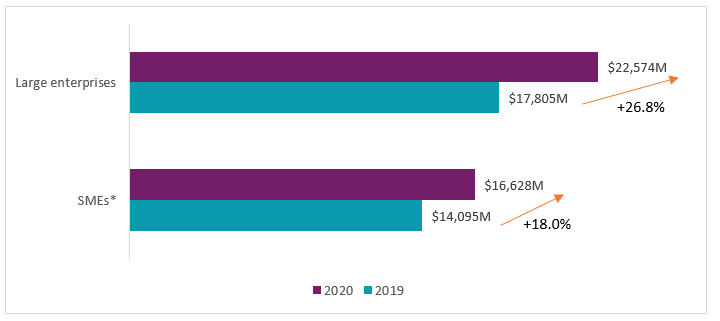

Box 3. Digitally delivered services exports surged in 2020

Although many types of services were hit hard by COVID-19 containment measures, services delivered digitally instead saw a large increase in 2020. For the full year, services exports delivered digitally rose 25.1% or $7.9 billion in value. Approximately one-third of the growth in value can be traced back to exports from SMEs, which rose 18.0% from the year prior, while digitally delivered services exports from large enterprises increased by 26.8%.

Figure 11: Canadian digitally delivered services exports, 2019 - 2020

Text version – Figure 11

| 2019 | 2020 | |

|---|---|---|

| SMEs* | 14,095 | 16,628 |

| Large enterprises | 17,805 | 22,574 |

* 0 to 499 employees

Source: Statistics Canada, Table 12-10-0146-01. Calculations by the Office of the Chief Economist.

D. Certain service-producing industries have gained popularity among SME exporters

SMEs in Canada comprise a group of highly heterogeneous enterprises, including those focused solely on local markets, such as fitness gyms and repair services, as well as enterprises that are also internally focused, such as auto-parts manufacturers or software services. The variations in the nature of businesses, among other factors, are determinants in the likelihood of SMEs engaging in export activities.

In 2020, professional, scientific and technical services and manufacturing were the two largest industries together accounting for over 40% of SME exporters. However, in the overall population of SMEs (exporters and non-exporters), the two industries represent less than one-fifth of all SMEs. Similarly, wholesale trade is overrepresented among exporters, with 11.0% industry share among exporters and 4.8% industry share in the overall population of SMEs. These features suggest that SMEs in these industries are more likely to export – which is consistent with the higher export propensity of those industries compared to the average (Table 2).

Table 2: Export propensity and share of SME exporters by industry, 2020

| Export propensity (%) | Share of SME exporters (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Agriculture and Mining | 10.7 | 5.3 |

| Construction | - | - |

| Manufacturing | 38.0 | 17.1 |

| Wholesale Trade | 28.1 | 11.4 |

| Retail Trade | 10.5 | 9.8 |

| Transportation and Warehousing | 26.7 | 16.2 |

| Professional, Scientific and Technical Services | 20.6 | 25.7 |

| Accommodation and Food Services | 3.9 | 2.6 |

| Other Services | - | - |

| Other industries | 6.8 | 12.0 |

| All Industries | 12.1 | 100.0 |

* Other industries include NAICS 51, 53, 56, 62, 71.

Source: Statistics Canada, SFG, 2020. Calculations by the Office of the Chief Economist.

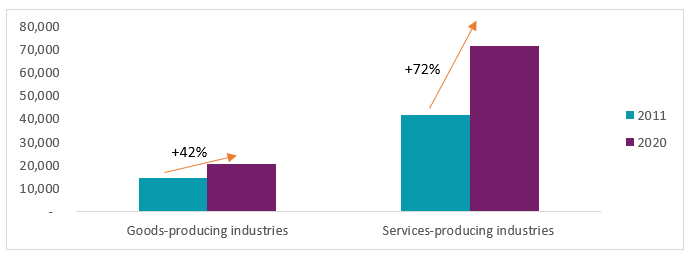

While the top two industries have remained consistent over the past decade, a notable trend has emerged: SMEs operating in the services sector have increased their prominence as exporters. Between 2011 and 2020, the number of SME exporters within services-producing industries surged by 72%. This growth was primarily propelled by industries such as professional, scientific, and technical services, as well as transportation and warehousing. In contrast, the number of SME exporters in goods-producing industries witnessed a slower growth rate of 42% (Figure 12). In particular, the manufacturing industry saw a decline in proportional representation among SME exporters, with its share decreasing by 3 percentage points since 2011.

Figure 12. Growth in number of SME exporters by industry type, 2011 - 2020 (percentage points)

Text version – Figure 12

| 2011 | 2020 | Growth | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Goods-producing industries | 14,579 | 20,672 | 42% |

| Services-producing industries | 41,674 | 71,768 | 72% |

* Construction and other services are not included due to lack of data.

Source: Statistics Canada, SFG, 2011 & 2020. Calculations by the Office of the Chief Economist.

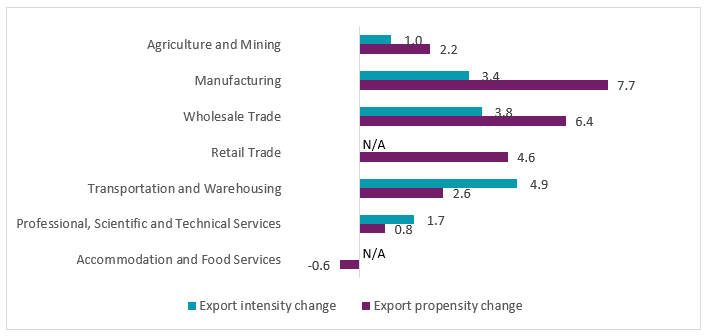

Not only has export propensity increased for most industries between 2011 and 2020, their export intensity has also posted growth (Figure 13). In other words, the proportion of exporters has increased, plus among those that exported, a larger share of their sales came from exporting. The largest export intensity increases were in transportation and warehousing, followed by wholesale trade and manufacturing. Additionally, the four industries with above average export propensity, (namely manufacturing, wholesale trade, transportation and warehousing, and professional, scientific and technical services) are also those with above-average shares of exports sales.

Figure 13. Change in export propensity and intensity by industry, 2011 – 2020 (percentage points)

Text version – Figure 13

| Export intensity change | Export propensity change | |

|---|---|---|

| Agriculture and Mining | 1.0 | 2.2 |

| Manufacturing | 3.4 | 7.7 |

| Wholesale Trade | 3.8 | 6.4 |

| Retail Trade | 4.6 | |

| Transportation and Warehousing | 4.9 | 2.6 |

| Professional, Scientific and Technical Services | 1.7 | 0.8 |

| Accommodation and Food Services | -0.6 |

* Construction, other services, and other industries are not included due to lack of data.

Source: Statistics Canada, SFG, 2011 & 2020. Calculations by the Office of the Chief Economist.

E. U.S. remains the largest export destination by far but its importance has declined

While the U.S. is by far the most important destination for SMEs exporting goods and services from Canada, a significant number of SMEs also export to non-U.S. markets, mostly in Europe and Asia. Moreover, the proportion of SMEs exporting to the U.S. has decreased slightly in every iteration of the SFG, from 89.3% in 2011 to 83.7% in 2020 (Figure 14). The COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 had a large impact on export markets; propensity to export to the U.S. and most other markets declined in 2020.

Figure 14. Percentage of SME Exporters exporting to the United States, 2011 - 2020

Text version – Figure 14

| 2011 | 2014 | 2017 | 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| United States | 89.3 | 89.2 | 87 | 83.7 |

Source: Statistics Canada, SFG, 2011, 2014, 2017, 2020. Calculations by the Office of the Chief Economist.

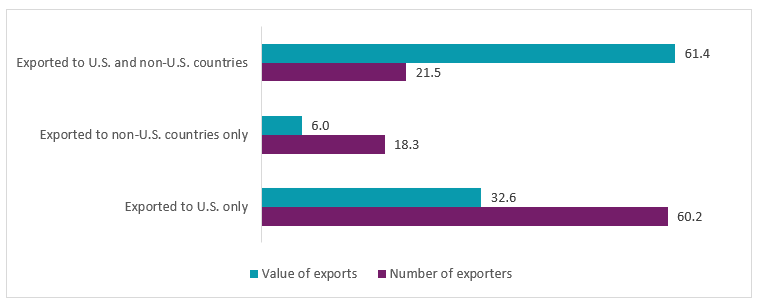

For goods exporters, roughtly 60% of SMEs have the U.S. as their sole export destination (Figure 15). 18% exported to only non-US destinations and the remaining nearly 22% exported to both US and non-US destinations. For export value, the trend changes, with over 60% of goods exports going to both US and non-US markets, and 33% going to the U.S. only. This reflects the size of enterprises exporting; large enterprises tend to export both to US and non-US destinations while most small firms focus solely on the US and a good number of small firms export only to non-US destinations. There is reason to believe that a good portion of the SMEs exporting only to non-US destinations are run by recent immigrants to Canada and take advantage of their networks to their home country (Blanchet, 2021)

An interesting finding is that while the share of U.S.-only exporters increased in 2020, the value share of exports from U.S.-only exporters declined to the lowest on record. A firm-level study conducted by the Office of the Chief Economist found that most new exporters choose the U.S. as their first market. While roughly half stop exporting after the first year, those that survive increase their export levels rapidly. As these companies grow and start exporting more, they are able to expand and diversify into other markets beyond the United States (Yu, 2019).

Figure 15. Distribution of SME goods exporters and export value by sales destination, 2020 (%)

Text version – Figure 15

| Number of exporters | Value of exports | |

|---|---|---|

| Exported to U.S. only | 60.2 | 32.6 |

| Exported to non-U.S. countries only | 18.3 | 6.0 |

| Exported to U.S. and non-U.S. countries | 21.5 | 61.4 |

Source: Statistics Canada, TEC, 2020. Calculations by the Office of the Chief Economist.

F. Exporters are more likely to engage in other international activities

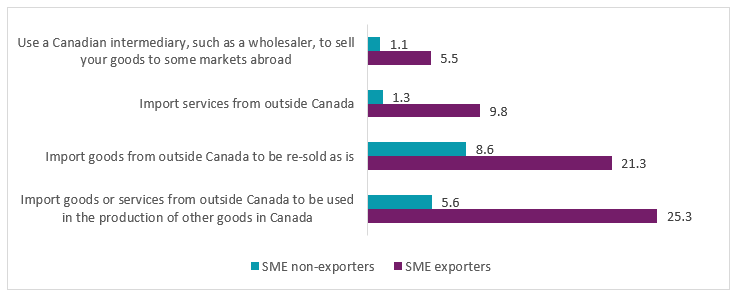

In addition to exporting, enterprises also engage in various international activities such as using intermediary companies for exporting, or importing goods and sevices, attracing foreign investment and investing in foreign companies. These activities are generally associated with higher productivity and employement growth, and are important ways to increase SMEs’ participation in global markets (OECD, 2018). Moreover, the increased importance of global value chains and cross-border e-commerce has created opportunities for SMEs to engage interantionally at lower costs (i.e. upstream supply). In 2020, 10.1% of SMEs in Canada imported goods to be re-sold as is, and 8.0% imported goods and services as inputs for production of other goods in Canada (Figure 16).

Figure 16. Share of SMEs engaged in international activities, 2020 (%)

Text version – Figure 16

| SME exporters | SME non-exporters | |

|---|---|---|

| Import goods or services from outside Canada to be used in the production of other goods in Canada | 25.3 | 5.6 |

| Import goods from outside Canada to be re-sold as is | 21.3 | 8.6 |

| Import services from outside Canada | 9.8 | 1.3 |

| Use a Canadian intermediary, such as a wholesaler, to sell your goods to some markets abroad | 5.5 | 1.1 |

| Have a product that is manufactured by a contracted company abroad | 6.6 | 1.5 |

| Engage in foreign direct investments | 0.8 | 0.3 |

| Relocate any business activities or employees from another country into Canada | 1.4 | 0.4 |

| Engage in other international business activities | 7.8 | 0.6 |

Source: Statistics Canada, SFG, 2020. Calculations by the Office of the Chief Economist.

SMEs’ importing activities are a lot more prevalent among SME exporters than non-exporters, with the proportion of SMEs that use imports as inputs being more than four times higher for exporters than for non-exporters. This relationship between importers and exporters has been previously analyzed in the trade literature and evidence shows causality effects in both directions. While importing higher quality products and embeded technology can help firms become more competitve internationally and enable them to start exporting (Goldberg et.al., 2010), exporting firms also become more productive and invest more in technology, which may increase the demand for high quality products and services (Lileeva and Trefler, 2010).

Similar differences between exporters and non-exporters are also idenfied in other types of internationalization activities, such as foreign contract manufacturing, indirect exports (intermediary firms that sells SMEs’ products abroad), foreign direct investment, etc. Once firms overcome sunk costs related to international activities such as aquiring information about markets, or undertaking organizational changes for engaging in global markets or making connections with international suppliers or buyers, it becomes easier to also participate in other international activities (Aristei et.al., 2013).

Conclusions

SMEs comprise the vast majority of businesses and employment opportunities in Canada. However, historically, only a small fraction of these enterprises have engaged in exports. Recognizing the potential for internationalization to boost productivity, foster innovation, and enhance fair trade outcomes, it becomes essential to identify the characteristics of SME exporters to drive economic growth. This report leverages Statistics Canada's surveys and databases to offer insights into the factors driving the growth in SME internationalization in Canada since 2011, which include:

- rise in the number of micro-sized SMEs entering the export market

- shift towards services exports, especially for micro-enterprises

- growth of exporters in services-producing industries, such as professional, scientific, and technical services and transportation and warehousing

- diversification of sales beyong the United States

- adoption of digital platforms and technologies

These findings provide policymakers with valuable information to enhance policies and support systems for SMEs. By creating a more favorable environment for SMEs to succeed in global markets, policymakers can play a vital role in promoting their ongoing growth, enhancing competitiveness, and ultimately fortifying Canada's economic landscape.

Reference

- Aristei, D., Castellani, D., & Franco, C. (2013). Firms’ exporting and importing activities: Is there a two-way relationship? Review of World Economics, 149, 55–84. DOI: 10.1007/s10290-012-0137-y

- Alvarez, R., & López, R. A. (2005). Exporting and performance: Evidence from Chilean plants. Canadian Journal of Economics/Revue canadienne d'économique, 38(4), 1384-1400. DOI: 10.1111/j.0008-4085.2005.00329.x

- Baldwin, J.R. and Gu, W. (2003), Export-market participation and productivity performance in Canadian manufacturing. Canadian Journal of Economics/Revue canadienne d'économique, 36: 634-657.

- Baldwin, J. R., Gu, W., Li, X., & Yan, B. (2013). Export Growth, Capacity Utilization, and Productivity Growth: Evidence from the Canadian Manufacturing Plants. Review of Income and Wealth, 59(4), 665–688. DOI: 10.1111/roiw.12028

- Bernard, A. B., Jensen, B. J., Redding, S. J., & Schott, P. K. (2007). Firms in International Trade. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 21(3), 105-130.

- Crespi, G., Criscuolo, C., & Haskel, J. (2008, May). Productivity, Exporting, and the Learning-by-Exporting Hypothesis: Direct Evidence from UK Firms. The Canadian Journal of Economics, 41(2), 619-638.

- Goldberg, P. K., Khandelwal, A. K., Pavcnik, N., & Topalova, P. (2010). Imported Intermediate Inputs and Domestic Product Growth: Evidence from India. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 125(4), 1727–1767.

- Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada (ISED) (2022). Key Small Business Statistics, 2022.

- Leung, D., Meh, C., & Terajima, Y. (2008). Firm Size and Productivity (Bank of Canada Working Paper No. 2008-45).

- Lileeva, A., & Trefler, D. (2010). Improved Access to Foreign Markets Raises Plant-Level Productivity... for Some Plants. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 125(3), 1051–1099.

- Melitz, M. J. (2003). The Impact of Trade on Intra-Industry Reallocations and Aggregate Industry Productivity. Econometrica, 71(6), 1695–1725.

- Melitz, M.J. and Trefler, D. (2012). Gains from Trade when Firms Matter. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 26, 91-118.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2018). Fostering Greater SME Participations in a Globally Integrated Economy [Discussion Paper].

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2023). Managing Shocks and Transitions: Future-Proofing SME and Entrepreneurship Policies.

- Statistics Canada. (2020). Canadian Survey on Business Conditions: Impact of COVID-19 on businesses in Canada, March 2020.

- World Trade Organization (WTO). (2019). World Trade Report 2019: The future of services trade

- Tran, T. (2021). 2020 Canadian export trends by size. Ottawa: Office of the Chief Economist, Global Affairs Canada.

- Yu, E. (2019). Size and pattern of exporter trade diversification: preliminary results from firm-level data Ottawa: Global Affairs Canada.

- Date modified: