Archived information

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

Canada's Services Trade Performance (2018)

Services are becoming a more important share of Canadian exports, reaching 17.0 percent in 2017 and even more on a value-added basis, due to the high domestic content of services and to the indirect contribution of services to the value of goods exports. Yet services still account for a smaller share of Canadian exports than they do for most other advanced countries. Canada performs well in a number of services sectors that rely on skilled people and on innovation, most notably research and development, finance, professional services and education. Services are important for Canada’s international competitiveness more broadly as they are important inputs into the production process and help facilitate trade. Increasingly, they are also bundled alongside goods as part of a trend towards “servicification”, and in many cases may be the largest component of goods trade.

The Services Sector in Canada

Services have come to dominate the economies of all advanced countries. As of 2017, services accounted for 70.5 percent of Canadian GDP, up from 57.3 percent in 1961. Most of the increase in the services share of the economy took place in the 1960s and 1980s. Since then, the increase has been much more modest; the share in 2017 is only slightly above the 1992 level. When measured by employment, the rise of services is even more pronounced, increasing from 65.4 percent in 1976 to 79.0 percent by 2017. The fact that services account for a larger share of the economy when measured by employment rather than by GDP reflects lower labour productivity in the services sector compared to goods-producing sectors.

Figure 1

Services Share of Canadian GDP and Employment, 1961-2017

Source: Statistics Canada

Figure 1 Text Alternative

Services Share of Canadian GDP and Employment, 1961-2017

| 1961 | 1962 | 1963 | 1964 | 1965 | 1966 | 1967 | 1968 | 1969 | 1970 | 1971 | 1972 | 1973 | 1974 | 1975 | 1976 | 1977 | 1978 | 1979 | 1980 | 1981 | 1982 | 1983 | 1984 | 1985 | 1986 | 1987 | 1988 | 1989 | 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Service Share GDP | 57.25% | 56.13% | 56.17% | 56.47% | 55.99% | 56.44% | 58.47% | 58.89% | 59.46% | 61.49% | 61.76% | 62.05% | 59.64% | 58.70% | 60.44% | 61.13% | 61.10% | 61.05% | 59.72% | 59.85% | 60.76% | 62.88% | 62.83% | 61.92% | 62.25% | 64.63% | 64.57% | 64.48% | 65.24% | 66.72% | 68.90% | 69.53% | 69.20% | 68.12% | 67.21% | 66.95% | 67.39% | 68.14% | 67.00% | 65.15% | 66.55% | 67.61% | 67.38% | 66.98% | 66.54% | 67.19% | 67.49% | 66.77% | 71.90% | 70.62% | 69.53% | 70.01% | 69.98% | 69.74% | 70.61% | 70.80% | 70.53% |

| Employment | 65.42% | 66.14% | 66.54% | 66.45% | 66.86% | 67.26% | 69.12% | 69.83% | 70.02% | 70.18% | 70.26% | 70.54% | 70.52% | 70.60% | 71.35% | 72.63% | 73.37% | 74.01% | 73.98% | 73.92% | 74.14% | 73.94% | 73.89% | 74.07% | 74.19% | 74.78% | 74.65% | 74.92% | 74.93% | 75.19% | 75.78% | 76.33% | 76.60% | 77.76% | 78.04% | 77.93% | 77.78% | 77.90% | 78.11% | 78.43% | 78.80% | 78.95% |

The share of services in the Canadian economy is smaller than in most other advanced countries. Economies with lower incomes per capita tend to have a lower share of services, although that does not explain Canada’s lower share. Rather, Canada has a remarkably diverse economy with both an above-average share of manufacturing, like Germany and Japan, and a high share of resources like Norway.

Real estate is the largest of the service sectors in Canada, when measured by contribution to GDP, and a sector for which there is minimal trade across borders. Public administration and other sectors that have large public components, namely education and health care, also account for a large share of service-sector GDP. These sectors will have traded components, most notably education, which will be covered later in this report, but as a share of their total value-added trade they represent a relatively small fraction. Service sectors that can largely be thought of as tradeable, such as finance and insurance, professional, and information and culture services, account for a relatively small share of services. The wholesale, retail, and transportation sectors might be thought of more as facilitating trade rather than tradeable in and of themselves.

Figure 1

Service Share of GDP – G7 and OECD, 2014

Source: OECD STAN Database, 2014

Figure 2 Text Alternative

Service Share of GDP – G7 and OECD, 2014

| 2014 | |

|---|---|

| Luxembourg | 86.84% |

| Greece | 80.35% |

| United Kingdom | 79.30% |

| France | 78.62% |

| United States | 77.88% |

| Netherlands | 77.65% |

| Belgium | 77.26% |

| Israel | 76.84% |

| Portugal | 76.03% |

| Denmark | 75.92% |

| Italy | 74.46% |

| Spain | 74.25% |

| Switzerland | 73.58% |

| Latvia | 73.30% |

| Sweden | 72.91% |

| Australia | 72.22% |

| New Zealand | 71.37% |

| Ireland | 71.05% |

| Japan | 71.03% |

| Iceland | 70.89% |

| Finland | 70.43% |

| Austria | 70.23% |

| Canada | 69.07% |

| Germany | 68.79% |

| Estonia | 67.79% |

| Slovenia | 64.85% |

| Hungary | 64.71% |

| Poland | 63.85% |

| Mexico | 63.48% |

| Chile | 62.88% |

| Slovak Republic | 61.13% |

| Türkiye | 60.67% |

| Norway | 60.32% |

| Korea | 59.61% |

| Czech Republic | 59.37% |

The services sector is large and diverse and accounts for nearly four out of every five jobs in Canada. But, there can be, at times, a perception that service-sector jobs are inferior to those in other sectors; there is no doubt that some service-sector jobs are relatively low-paid. For example, jobs in accommodation and food, and retail (within wholesale and retail) are indeed relatively low-paid. Professional, finance and insurance, and information and cultural services, in contrast, are among the highest-paid sectors of the economy. In fact, these potentially tradeable services sectors all have average weekly wages above those in manufacturing and account for 50 percent more of the economy than does manufacturing: 15.6 percent of GDP vs. 10.5 percent of GDP for manufacturing. In tradeable services, wages are as much as 37 percent higher than in manufacturing.Footnote 1

Figure 3

Average Weekly Wages, 2017

Source: OECD STAN Database, 2014

Figure 3 Text Alternative

Average Weekly Wages, 2017

| Forestry | 1,123 |

| Resource Extraction | 2,018 |

| Utilities | 1,861 |

| Construction | 1,218 |

| Manufacturing | 1,097 |

| Wholesale & Retail | 745 |

| Transportation | 1,041 |

| Information & Culture | 1,280 |

| Finance & Insurance | 1,306 |

| Real Estate | 984 |

| Professional | 1,343 |

| Management | 1,639 |

| Business Services | 789 |

| Education | 1,041 |

| Health Care | 890 |

| Entertainment | 592 |

| Accommodation & Food | 383 |

| Other | 805 |

| Public Administration | 1,256 |

Value-added Trade and Servicification

As described in the body of this report, services account for 17.0 percent of Canada’s total exports. This is based on a simple measure of the value of goods and services as they cross the border, or what is known as gross exports. An alternative method of measuring the value of exports is to use value added. A car that crosses the border, for example, will contain many imported parts. On a value added basis, the value of imported inputs would be removed leaving only the value that was added in the domestic economy. Removing the value of imported inputs, because it impacts goods-producing sectors most, raises the share of services in exports to 28.7 percent. Similarly, a large share of the cost of producing that car comes not only from the automotive sector, but also from a number of additional supporting sectors, many of which are services – everything from the company hired to clean the offices and dispose of the garbage to financing and R&D. When measured on a value-added basis, the value of the product crossing the border is attributed to each of the sectors that contributed to its production. The net effect of making all of these changes to the way in which exports are measured greatly increases the share of services. On a value-added basis, services account for 45.2 percent of exports.Footnote 2

Figure 4

Services Share of Exports, 2017

Source: Statistics Canada, 2017

Figure 4 Text Alternative

Services Share of Exports, 2017

| Services in Gross Exports* | Services in Value-Added Exports** | Services embodied in Value-Added Exports** | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Services | 17.00% | 28.70% | 45.20% |

In most advanced countries, including Canada, manufacturing has become a declining sector of the economy. Some of that decline can be attributed to the manufacturing sector outsourcing activities to other sectors, most notably services.Footnote 3 For example, if a manufacturing firm employs accountants, the salaries of those workers contribute to the manufacturing sector. If, however, that same manufacturing firm hires an accounting company to do the same job, it now becomes part of the service sector. This outsourcing of services is more than just a statistical issue. As firms specialize, they have increased incentives to become more productive and to innovate. Even if not traded directly, these supporting services can make an important contribution to the competitiveness of the goods and services that are traded.Footnote 4 Having access to high quality and innovative services as both direct inputs as well as for facilitating trade, such as through efficient transportation systems, telecommunications systems, and finance, can have a significant effect on competitiveness.Footnote 5

In addition to goods-producing sectors outsourcing services, many are increasingly incorporating services into their products. The National Board of Trade in Sweden coined the term “servicification” to describe the growing share of services embodied in goods.Footnote 6 An often cited example is jet engines, which may be sold at, or even below, cost, with profits derived largely from the maintenance contracts. In some instances, the makers of the engines may not even charge for the engines themselves, but rather charge the aircraft manufacturer or airline for the use of the engine, such as per hour or distance travelled, blurring the line between manufacturing and services.Footnote 7 Higher profit margins and a more stable income flow are given as the reasons for the change in business model,Footnote 8 but it is the use of data that has facilitated the change. The ability to embed sensors in products allows for a constant stream of information about the status of the product and how it is being used. An additional benefit is that servicification changes the relationship between producer and consumer. Rather than a one-off sale, producers enter into a long-term relationship with the consumer allowing them to know more about how their product is used, which in turn creates a positive feedback loop to future innovation.

It is not possible to know how far such trends will go or what industries will follow the servicification model, but it is clear that as manufacturers increasingly buy, produce, sell and export services,Footnote 9 the line between goods and services will continue to blur.

The Services Sector in Canada

The share of services in Canada’s total trade has been rising, but the increase has not been steady – especially for imports. As of 2017, services accounted for 17.0 percent of Canada’s exports of goods and services and 19.4 percent of imports.Footnote 10 For exports, this is up sharply from 12.7 percent in 1990. For imports, however, it is up only marginally from 19.2 percent reached in 1991. For both exports and imports, the share of services dipped in the first half of the 1990s. These declines were likely the result of a rapid acceleration in goods trade linked to a rebound in the U.S. economy following the recession of 1989, and further boosted following the implementation of NAFTA in 1994. Since those dips, the shares of services in both exports and imports increased fairly steadily and were punctuated by spikes immediately following the global financial crisis; these spikes were due to a sharp drop in exports and imports of goods.Footnote 11

Figure 5

Services Share of Total Trade, 1981-2017

Source: Statistics Canada

Figure 5 Text Alternative

Services Share of Total Trade, 1981-2017

| 1981 | 1982 | 1983 | 1984 | 1985 | 1986 | 1987 | 1988 | 1989 | 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exports | 11.27% | 11.31% | 11.43% | 10.33% | 10.76% | 11.84% | 11.88% | 12.02% | 12.51% | 12.66% | 13.45% | 13.03% | 12.58% | 12.05% | 11.55% | 12.18% | 12.25% | 13.07% | 12.55% | 12.23% | 12.58% | 13.45% | 13.72% | 13.93% | 14.00% | 14.27% | 14.15% | 14.11% | 17.61% | 16.40% | 15.59% | 16.20% | 16.27% | 15.66% | 16.53% | 17.27% | 17.03% |

| Imports | 15.52% | 17.71% | 17.30% | 15.43% | 15.39% | 15.77% | 16.07% | 15.96% | 16.85% | 18.39% | 19.24% | 18.86% | 18.51% | 16.85% | 16.04% | 16.54% | 15.30% | 15.16% | 15.12% | 14.99% | 15.72% | 16.09% | 17.07% | 17.12% | 16.93% | 16.98% | 17.53% | 17.68% | 20.23% | 19.69% | 18.88% | 19.07% | 19.26% | 18.94% | 19.10% | 19.45% | 19.38% |

Figure 6

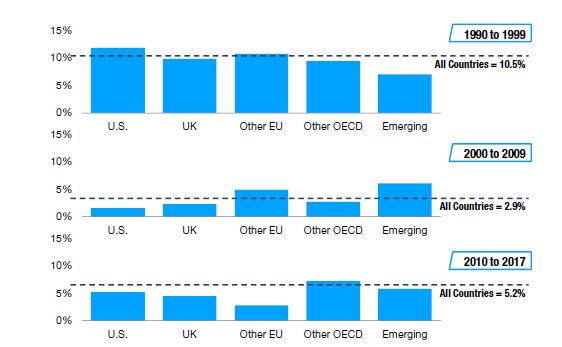

Growth in Services Exports by Major Region (Compound Average Annual Growth Rate)

Source: Statistics Canada

Figure 6 Text Alternative

Growth in Services Exports by Major Region (Compound Average Annual Growth Rate)

| 90s | 00s | 10s | |

|---|---|---|---|

| U.S. | 11.80% | 1.60% | 5.20% |

| UK | 9.80% | 2.30% | 4.50% |

| Other EU | 10.70% | 4.90% | 2.80% |

| Other OECD | 9.40% | 2.70% | 7.20% |

| Emerging | 7% | 6.10% | 5.80% |

Even for exports, the growth in services has not been even – there are significant differences in service export performance across regions and time periods. The period from 1990 to 1999 saw particularly rapid growth, with Canada’s service exports growing at an average annual rate of 10.5 percent for the decade with growth driven by advanced countries and spread relatively evenly among regions. Growth slowed considerably between 2000 and 2009 to a rate of just 2.9 percent. The overall rate was dragged down by two notable events in this decade – the first event occurred at the beginning of the decade with the bursting of the “dot-com bubble”; the second event was the global financial crisis at the end of the decade. The effects, however, were not evenly distributed among trading partner regions. Growth in services exports to emerging markets slowed only modestly from the previous decade whereas growth to advanced countries slowed sharply. Since 2010, Canadian service export growth picked up to 5.2 percent. Exports to emerging markets continued to slow, although modestly, from 7.0 percent in the 1990-1999 period, to 6.1 percent during the 2000-2009 period and to 5.8 percent in the most recent decade, but exports to these markets are still strong by most measures. With the exception of “other EU” countries (i.e. EU countries excluding the United Kingdom), which had a particularly slow recovery from the global crisis, growth picked up in all advanced regions compared to the 2000-2009 period.

Figure 7

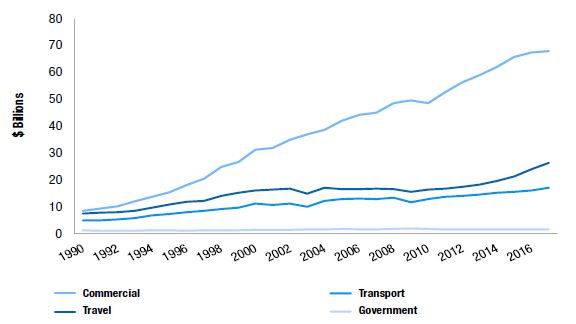

Services Exports by Type, 1990-2017

Source: Statistics Canada

Figure 7 Text Alternative

Services Exports by Type, 1990-2017

| 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Travel | 7,398 | 7,691 | 7,898 | 8,480 | 9,558 | 10,819 | 11,749 | 12,221 | 14,019 | 15,141 | 15,997 | 16,437 | 16,741 | 14,776 | 16,980 | 16,533 | 16,459 | 16,618 | 16,544 | 15,547 | 16,320 | 16,624 | 17,388 | 18,201 | 19,623 | 21,157 | 23,886 | 26,352 |

| Transport | 4,920 | 4,883 | 5,232 | 5,790 | 6,678 | 7,207 | 7,905 | 8,407 | 9,143 | 9,691 | 11,196 | 10,625 | 11,060 | 9,942 | 12,074 | 12,872 | 12,999 | 12,814 | 13,246 | 11,624 | 12,757 | 13,588 | 14,031 | 14,453 | 15,171 | 15,556 | 16,067 | 17,013 |

| Commercial | 8,510 | 9,203 | 10,193 | 11,978 | 13,721 | 15,357 | 17,970 | 20,445 | 24,750 | 26,664 | 31,095 | 31,849 | 34,877 | 36,970 | 38,525 | 41,917 | 44,144 | 44,991 | 48,606 | 49,502 | 48,490 | 52,577 | 56,274 | 59,014 | 61,989 | 65,705 | 67,366 | 67,849 |

| Government | 1,165 | 1,114 | 1,102 | 1,048 | 1,233 | 1,188 | 1,109 | 1,161 | 1,134 | 1,273 | 1,376 | 1,410 | 1,385 | 1,506 | 1,548 | 1,656 | 1,616 | 1,604 | 1,679 | 1,807 | 1,679 | 1,567 | 1,530 | 1,468 | 1,523 | 1,565 | 1,566 | 1,571 |

Within services trade there are four broad categories: commercial, travel, transportation, and government. Among Canadian services exports, commercial services are by far the largest component and have been the fastest growing. In 1990, commercial services accounted for only 38.7 percent of Canada’s total services; by 2017, that share had increased to 60.2 percent. Since 2010, however, the export share of commercial services has fallen slightly as growth slowed to an average annual rate of 4.9 percent. That rate still outpaced transportation, which grew at an average rate of 4.2 percent, but was handily outpaced by travel, which grew at a rate of 7.1 percent.

TRANSPORTATION SERVICES covers payments related to the international transportation of people or goods.Footnote 12 Passenger transportation includes fares and related expenditures for international transport of non-residents by resident carriers (exports) and residents by non-resident carriers (imports). For freight, by international convention, transportation costs up to the customs frontier are attributed to the exporting country, and costs beyond the customs frontier are attributed to the importing country.

Figure 8

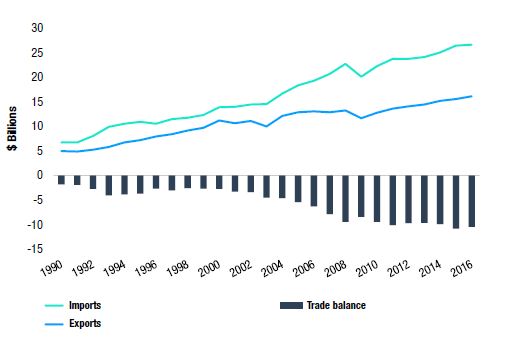

Trade in Transportation Services, 1990-2016, $ Billions

Source: Statistics Canada

Figure 8 Text Alternative

Trade in Transportation Services, 1990-2016, $ Billions

| 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exports | 4,920 | 4,883 | 5,232 | 5,790 | 6,678 | 7,207 | 7,905 | 8,407 | 9,143 | 9,691 | 11,196 | 10,625 | 11,060 | 9,942 | 12,074 | 12,872 | 12,999 | 12,814 | 13,246 | 11,624 | 12,757 | 13,588 | 14,031 | 14,453 | 15,171 | 15,556 | 16,067 |

| Imports | 6,746 | 6,760 | 7,989 | 9,883 | 10,528 | 10,911 | 10,567 | 11,417 | 11,759 | 12,307 | 13,916 | 13,970 | 14,438 | 14,508 | 16,682 | 18,333 | 19,280 | 20,643 | 22,682 | 20,076 | 22,209 | 23,674 | 23,735 | 24,070 | 25,048 | 26,367 | 26,561 |

| Balance | -1,826 | -1,877 | -2,757 | -4,093 | -3,849 | -3,703 | -2,662 | -3,010 | -2,616 | -2,617 | -2,719 | -3,345 | -3,378 | -4,566 | -4,609 | -5,461 | -6,281 | -7,828 | -9,436 | -8,452 | -9,452 | -10,086 | -9,703 | -9,617 | -9,877 | -10,811 | -10,494 |

Canadian exports of transportation services grew rapidly in the 1990s, but then shifted to a lower growth path after 2000, largely moving in lockstep with slowing Canadian merchandise export growth. Imports, on the other hand, were growing at a comparable rate to exports in the 1990s but then accelerated between 2000 and 2007. Growth in imports of transportation services related to goods continued at the rapid pace of the previous decade, just as export growth was slowing, and on its own would have contributed to a widening trade deficit. But growth related to the movement of people accelerated in the middle of the decade, likely related to a change in the policy environment related to air travel that started to have an impact in the middle of the decade, and by accelerating the access of Canadians to foreign carriers, further widened the gap with exports.Footnote 13 Although potentially contributing to a widening of the transportation deficit, such policies, by reducing the cost of air travel thus facilitating the movement of goods and especially business people by air, have been shown to have a positive impact on both goods and services trade and likely foreign direct investment.Footnote 14 Since 2009, the deficit has once again levelled off.

Figure 9

Trade in Transportation Services, 1990-2016, $ Billions

Source: Statistics Canada

Figure 9 Text Alternative

Trade in Transportation Services, 1990-2016, $ Billions

| 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exports | Passenger | 1,200 | 1,058 | 1,156 | 1,211 | 1,494 | 1,719 | 2,002 | 2,176 | 2,435 | 2,702 | 3,349 | 3,183 | 3,221 | 2,275 | 2,750 | 2,709 | 2,587 | 2,531 | 2,692 | 2,097 | 2,688 | 3,122 | 3,287 | 3,383 | 3,355 | 3,523 |

| Not | 3,720 | 3,825 | 4,076 | 4,579 | 5,184 | 5,488 | 5,903 | 6,231 | 6,708 | 6,989 | 7,847 | 7,442 | 7,839 | 7,667 | 9,324 | 10,163 | 10,412 | 10,283 | 10,554 | 9,527 | 10,069 | 10,466 | 10,744 | 11,070 | 11,816 | 12,033 | |

| Imports | Passenger | -2,371 | -2,341 | -2,575 | -2,972 | -2,968 | -3,293 | -3,491 | -3,695 | -3,748 | -3,716 | -3,986 | -4,130 | -3,977 | -4,157 | -4,875 | -5,717 | -6,185 | -6,936 | -7,062 | -6,889 | -7,466 | -7,764 | -7,966 | -8,159 | -8,087 | -8,355 |

| Not | -4,375 | -4,419 | -5,414 | -6,911 | -7,560 | -7,618 | -7,076 | -7,722 | -8,011 | -8,591 | -9,930 | -9,840 | -10,461 | -10,351 | -11,807 | -12,616 | -13,095 | -13,707 | -15,620 | -13,187 | -14,743 | -15,910 | -15,769 | -15,911 | -16,961 | -18,012 |

In addition to moving with the broad trend in goods trade, the composition of trading partners also has a significant effect on the transportation services deficit; more distant trading partners involve greater transport costs. By far the greatest contributor to the increase in Canada’s transportation services trade deficit is a sharp increase in the deficit for water transport with non-U.S. trade partners. As of 2016, Canada’s trade deficit in water transport with non-U.S. partners stood at $8.7 billion, or 82 percent of Canada’s overall trade deficit in transportation services. The next largest deficit is in air transport with the United States, at $2.8 billion, and is largely offset by a $1.7-billion surplus in land transport with the United States.

Transportation services are not only about the movement of goods, but also about the movement of people. Broadly speaking, growth in trade in transportation services related to the movement of people has not grown as quickly as that for goods, and exports have not grown as quickly as imports. Exports of passenger services have increased at an average annual rate of 4.6 percent since 1990 vs. 5.0 percent for imports. It is also notable that the fastest growth occurred in the 1990s for exports, but for imports accelerated in the period between 2000 and the start of the global financial crisis. Not surprisingly, air transportation accounts for the vast majority of international service imports related to the movement of people. As a percentage of bilateral trade, the deficit related to the movement of people is significantly greater than that for goods, but somewhat smaller in absolute terms.

Figure 10

Trade in Transportation Services, 1990-2016, $ Billions

Source: Statistics Canada

Figure 10 Text Alternative

Trade in Transportation Services, 1990-2016, $ Billions

| 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exports | 7,398 | 7,691 | 7,898 | 8,480 | 9,558 | 10,819 | 11,749 | 12,221 | 14,019 | 15,141 | 15,997 | 16,437 | 16,741 | 14,776 | 16,980 | 16,533 | 16,459 | 16,618 | 16,544 | 15,547 | 16,320 | 16,624 | 17,388 | 18,201 | 19,623 | 21,157 | 23,886 |

| Imports | 12,757 | 13,753 | 14,255 | 14,359 | 13,678 | 14,093 | 15,353 | 15,873 | 16,029 | 16,975 | 18,337 | 18,344 | 18,223 | 18,526 | 19,876 | 21,870 | 23,396 | 26,422 | 28,645 | 27,680 | 30,895 | 32,974 | 35,030 | 36,161 | 38,005 | 38,525 | 38,096 |

| Balance | 5,359 | 6,062 | 6,357 | 5,879 | 4,120 | 3,274 | 3,604 | 3,652 | 2,010 | 1,834 | 2,340 | 1,907 | 1,481 | 3,750 | 2,896 | 5,338 | 6,937 | 9,804 | 12,101 | 12,133 | 14,574 | 16,351 | 17,643 | 17,960 | 18,382 | 17,368 | 14,210 |

TRAVEL SERVICES are in reality a mix of goods and services consisting of all purchases by individuals for own use or as gifts during visits to another country. This includes all spending, such as for lodging and food, but not the actual passenger fares, which are included under transportation services. Simply put, travel imports comprise spending by Canadians while traveling abroad while travel exports comprise the value of spending by foreigners while in Canada. In both cases, spending excludes the cost of transport to and from Canada.

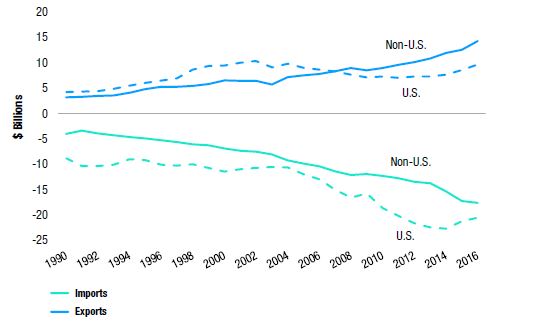

The travel services deficit expanded significantly in the first decade of the new millennium after shrinking somewhat in the 1990s. The expansion of the deficit can be traced to three economic factors.Footnote 15 The first is the value of the Canadian dollar. A strong dollar makes it relatively less expensive for Canadians to travel abroad and more expensive for foreigners to travel to Canada while a weak dollar would have the opposite effect. In the opening years of the millennium, the Canadian dollar appreciated significantly from US$0.64 in 2002 to achieving parity with it in 2011. The Canadian dollar has weakened somewhat in the last few years, and a small uptick can be seen in exports and a levelling off of imports. The second factor was a tightening of the Canada- U.S. border in the years following the tragic events of 9/11 and the consequent sharp fall in travel receipts from the United States. General economic conditions can be considered the third factor that had an impact on trade in travel services. Canadians tend to spend more on travel when economic conditions in Canada are solid while foreigners will spend more when economic conditions in their own countries are strong. Historically, it was the economic situation in the United States that was most important for Canadian travel exports, with the bursting of the dot-com bubble around 2000 and the global financial crisis contributing to the decline in Canadian travel exports to the U.S. market in those years. More recently, strong growth in emerging markets, China in particular, is a likely contributor to the rapid increase in travel imports from non-U.S. sources. Although growth in Canadian travel spending (i.e. imports) in non-U.S. destinations has grown faster, Canadians still spend more on trips in the United States. Travel spending by non-U.S. foreigners in Canada (exports), on the other hand, now exceeds spending by Americans after years of steady growth and a dip in spending by Americans between 2002 and 2009. Over the past four years, growth by both groups (U.S. and non-U.S.) is now growing at similar rates. Canada does have large deficits for both U.S. and non-U.S. travel.

Figure 11

Travel Exports by Type, 1990-2016, $ Billions

Source: Statistics Canada

Figure 11 Text Alternative

Travel Exports by Type, 1990-2016, $ Billions

| 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Business | 1,549 | 1,482 | 1,547 | 1,642 | 1,809 | 1,988 | 2,226 | 2,461 | 2,772 | 2,897 | 2,920 | 2,658 | 2,737 | 2,381 | 2,659 | 2,789 | 2,890 | 2,891 | 3,020 | 2,530 | 2,710 | 2,864 | 2,899 | 2,974 | 2,975 | 3,091 | 3,259 |

| Healtd | 68 | 68 | 68 | 66 | 70 | 86 | 87 | 88 | 90 | 92 | 94 | 98 | 100 | 103 | 106 | 117 | 121 | 126 | 130 | 135 | 141 | 145 | 148 | 150 | 158 | 162 | 163 |

| Education | 769 | 865 | 915 | 810 | 778 | 783 | 765 | 824 | 849 | 844 | 914 | 1,084 | 1,234 | 1,422 | 1,868 | 1,939 | 2,212 | 2,465 | 2,772 | 3,215 | 3,510 | 3,857 | 4,342 | 4,815 | 5,295 | 5,827 | 6,565 |

| Other Personal | 5,012 | 5,276 | 5,368 | 5,962 | 6,901 | 7,962 | 8,671 | 8,848 | 10,307 | 11,309 | 12,069 | 12,597 | 12,671 | 10,871 | 12,347 | 11,688 | 11,235 | 11,136 | 10,623 | 9,668 | 9,959 | 9,758 | 9,998 | 10,261 | 11,196 | 12,077 | 13,899 |

Travel spending by individuals is mostly for personal reasons, such as vacations. This type dominates spending by Canadians, accounting for 80.2 percent of the value of imports, but vacation spending is a somewhat less important source of foreign spending in Canada, accounting for 58.2 percent of travel exports in 2016. Probably because it is largely discretionary, this type of spending tends to be more volatile than other types with the shares varying considerably over time. Personal travel spending is even more dominant in its contribution to the trade deficit. Spending by Canadians abroad was more than two times as great as that spent by foreigners in Canada, a situation that is not likely to change until Canada improves its weather and builds the equivalent of the Louvre. After travel for personal reasons, business travelFootnote 16 is the next most important, though declining, share of travel exports. In 1990, business accounted for 20.9 percent of Canadian travel exports and 16.1 percent of imports; by 2016, these shares had fallen to 13.6 percent and 12.4 percent, respectively. Canada’s trade deficit in business travel has been a fairly stable share element of bilateral trade throughout the period. Travel for the purposes of education, while accounting for a small share of imports, is a fast-growing share of exports. From 2000 onward, travel exports related to education have grown at an average annual rate of 13.1 percent, far outpacing growth of travel service exports overall, which grew at an annual rate of 2.5 percent over the same period. As a result, Canada now has a large trade surplus in education, reaching $4.4 billion in 2016.Footnote 17 As recently as 2000, Canada had a trade deficit in this category, demonstrating just how quickly the trade situation can change. Travel spending for health reasons still accounts for a negligible share of both exports and imports.

Figure 12

Trade in Travel Services by Partner, 1990-2016, $ Billions

Source: Statistics Canada

Figure 12 Text Alternative

Trade in Travel Services by Partner, 1990-2016, $ Billions

| 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exports | U.S. | 4,229 | 4,367 | 4,414 | 4,878 | 5,469 | 6,027 | 6,489 | 6,921 | 8,606 | 9,365 | 9,449 | 9,972 | 10,328 | 9,080 | 9,858 | 8,968 | 8,671 | 8,271 | 7,625 | 7,077 | 7,318 | 7,071 | 7,296 | 7,340 | 7,702 | 8,571 |

| Other | 3,169 | 3,324 | 3,483 | 3,601 | 4,089 | 4,792 | 5,260 | 5,300 | 5,412 | 5,776 | 6,548 | 6,465 | 6,413 | 5,696 | 7,122 | 7,565 | 7,788 | 8,347 | 8,919 | 8,469 | 9,002 | 9,553 | 10,092 | 10,861 | 11,921 | 12,586 | |

| Imports | U.S. | -8,786 | -10,347 | -10,338 | -10,068 | -9,044 | -9,144 | -10,062 | -10,280 | -9,951 | -10,685 | -11,410 | -11,027 | -10,693 | -10,512 | -10,654 | -12,019 | -12,998 | -15,023 | -16,537 | -15,756 | -18,607 | -20,202 | -21,614 | -22,429 | -22,661 | -21,241 |

| Other | -3,970 | -3,405 | -3,916 | -4,291 | -4,634 | -4,948 | -5,290 | -5,593 | -6,078 | -6,291 | -6,927 | -7,317 | -7,529 | -8,014 | -9,222 | -9,851 | -10,397 | -11,398 | -12,108 | -11,924 | -12,288 | -12,772 | -13,417 | -13,732 | -15,344 | -17,284 |

GOVERNMENT SERVICES cover any payments made by or to governments and international organizations including everything from payments for visas, to purchases by embassies and embassy staff. Government services will not be covered in any detail in this report. Trade in government services is relatively small, representing a shrinking share of Canada’s international trade in services.

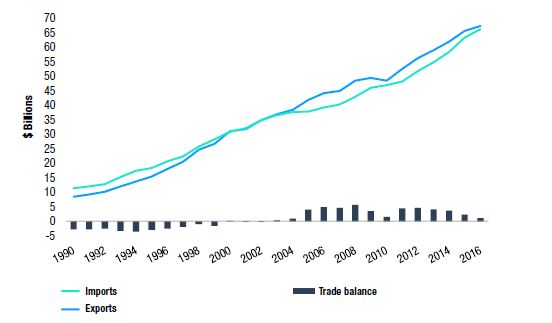

COMMERCIAL SERVICES include a wide range of services with their common factor largely being that they are not included in other categories of trade. Commercial services are the fastest growing type of services exports by a wide margin - though not this year. The remainder of this feature will focus on trade in commercial services.

Figure 13

Trade in Commercial Services, 1990-2016, $ Billions

Source: Statistics Canada

Figure 13 Text Alternative

Trade in Commercial Services, 1990-2016, $ Billions

| 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exports | 8,510 | 9,203 | 10,193 | 11,979 | 13,721 | 15,357 | 17,970 | 20,445 | 24,750 | 26,664 | 31,095 | 31,849 | 34,876 | 36,970 | 38,525 | 41,917 | 44,144 | 44,991 | 48,606 | 49,502 | 48,490 | 52,577 | 56,274 | 59,014 | 61,989 | 65,705 | 67,366 | 67,849 |

| Imports | 11,385 | 12,035 | 12,769 | 15,258 | 17,387 | 18,333 | 20,599 | 22,307 | 25,789 | 28,323 | 30,948 | 32,141 | 34,907 | 36,681 | 37,636 | 37,934 | 39,208 | 40,349 | 42,912 | 46,006 | 47,067 | 48,202 | 51,766 | 54,872 | 58,395 | 63,395 | 66,346 | 66,925 |

| Balance | -2,875 | -2,832 | -2,576 | -3,279 | -3,666 | -2,976 | -2,629 | -1,862 | -1,039 | -1,659 | 147 | -292 | -31 | 289 | 889 | 3,983 | 4,936 | 4,642 | 5,694 | 3,496 | 1,423 | 4,375 | 4,508 | 4,142 | 3,594 | 2,310 | 1,020 | 924 |

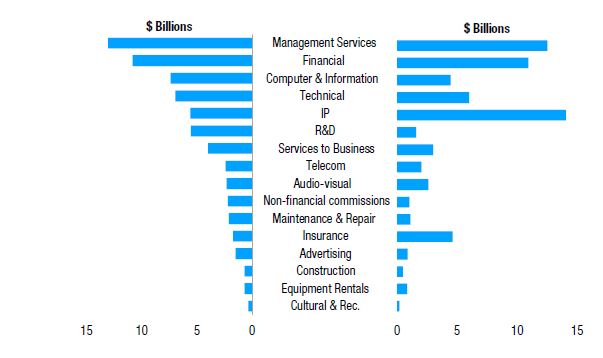

Canadian exports of commercial services grew at an average annual rate of 8.0 percent since 1990, outpacing import growth, which expanded at an average rate of 6.8 percent. Canada’s trade in commercial services is also balanced; Canada ran a small trade deficit in commercial services in every year of the 1990s but then switched to a small surplus in the early 2000s, which it still keeps.

Figure 14

Canadian Commercial Service Exports by Region, 2016

Source: Statistics Canada, 2016

Figure 14 Text Alternative

Canadian Commercial Service Exports by Region, 2016

| Region | Share of total Exports, 2016 | Growth, 2000-2016 |

|---|---|---|

| United states | 61.90% | 99.50% |

| Europe | 19.50% | 173.30% |

| Antilles | 6.40% | 464.50% |

| Africa & MENA | 6.40% | 18.40% |

| Asia | 4.80% | 44.50% |

| South & Central America | 3.00% | 123.60% |

| Oceania | 1.30% | 194.30% |

Commercial service exports are less dependent on the United States than are goods exports, with 62.2 percent of commercial service exports bound for the United States in 2017 compared to 74.8 percent of goods exports.Footnote 18 In other ways, however, commercial services exports are less diversified than goods: in the same year, 39.9 percent of commercial service exports to non-U.S. destinations were bound for emerging markets compared to a slightly higher 42.4 percent for goods.Footnote 19 Canadian commercial service exports are more likely to go to other advanced countries. In addition to the high share for the United States, the EU receives an outsized portion of Canadian commercial service exports compared to that region’s share for goods. Even more importantly, growth in Canadian commercial service exports to the EU has been among the highest of any region resulting in its share increasing at a steady pace. Asia, on the other hand, received only 4.8 percent of Canadian commercial service exports in 2016, and the rate of growth since 2000 has been among the weakest. South and Central America has an even smaller share at 3.0 percent in 2016, and while growth is significantly higher than that for Asia, it is only on par with growth in commercial services overall and therefore that region’s share has not improved to any great extent. Africa’s share is even smaller and has seen the slowest growth of any region. A notable exception to the trend of most Canadian commercial service exports going to advanced economies is the Antilles,Footnote 20 which had the third-highest share of any region and by far the fastest growth. There is no doubt that this region’s role as a destination for foreign direct investment (FDI), including FDI from Canada, is the reason for this outsized performance.

Figure 15

Top Destinations for Canadian Commercial Service Exports (excluding the U.S.), 2016

Source: Statistics Canada, 2016

Figure 15 Text Alternative

Top Destinations for Canadian Commercial Service Exports (excluding the U.S.), 2016

| 2016 | Growth* 2010-16 | |

|---|---|---|

| United Kingdom | 4,397 | 7.0% |

| Bermuda | 2,025 | 14.6% |

| Switzerland | 1,838 | 13.1% |

| France | 1,367 | 4.9% |

| Germany | 1,106 | 5.0% |

| Ireland | 810 | 2.9% |

| Japan | 784 | 2.3% |

| Belgium/Lux | 766 | 14.2% |

| Netherlands | 746 | 9.1% |

| Australia | 687 | 6.7% |

| Mexico | 664 | 7.8% |

| Sweden | 658 | 4.0% |

| China | 562 | 3.6% |

| Hong Kong | 437 | 3.7% |

| Barbados | 402 | 2.5% |

An examination of the top destinations, excluding the United States, for Canadian commercial service exports reinforces the link between exports and advanced countries and financial centres. Of the top 15 destinations, the only economies that would not fall into one of these two groups is Mexico, ranked in 11th position, and China, at 13th. The remainder are all financial centres, such as Bermuda, Hong Kong, and Barbados, or rich economies, such as France, Germany, Japan, Australia, and Sweden. Alternatively, they could be considered a combination of the two, such as the United Kingdom, Switzerland, Ireland, Belgium and Luxembourg, and the Netherlands. As previously noted, Canadian commercial service exports are remarkably concentrated: the United States plus the next 15 most important destinations account for 87.5 percent of exports. The addition of a further 15 destinations adds only another 4.3 percentage points to the total.

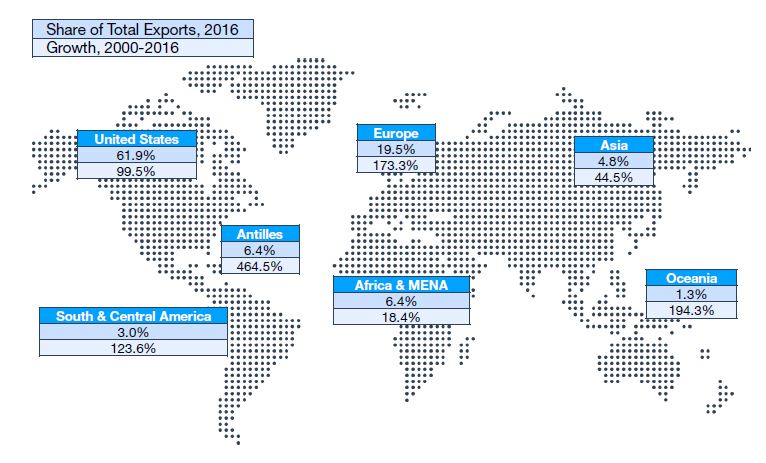

Management services is the single most important type of Canadian commercial service exports and includes professional and management consulting services as well as payments between affiliates and parent companies. The most important sub-category of this group is legal services, which accounts for about one-tenth of Canadian exports in this category. Financial services, which follows management in importance, includes various fees, margins and commissions relating to the cross-border provision of financial services. In 2016, roughly 40 percent of the value of this category was accounted for by financial intermediation. Computer and information services includes hardware- and software-related services such as licences for using software, web-hosting, and payments for maintaining and repairing computer systems. Information services means access to databases, data storage and dissemination and news agency services. Computer services account for the vast majority of the value in this category. Technical services includes the cross-border delivery of architectural and engineering services, which account for just under half of Canadian exports in this category and a broad category of other technical services, including environmental services, which account for a little more than half of the value. Charges for the use of intellectual property (IP) is the single largest import category and fifth most important category of Canadian commercial service exports. This category is one of only five areas where Canada has a trade deficit and is by a wide margin the largest area of deficit. Charges for the use of IP includes a number of sub-categories. Canada has a deficit in all sub-categories, but by far the largest is related to patents and industrial design followed by software and other royalties, and franchises. Trademarks and copyrights are relatively small in terms of both deficits and in terms of importance for Canadian exports. Although Canada has a large deficit in IP, Canada has a sizable surplus in R&D that is related to the outright purchase or sale of ownership related to the outcome of R&D. Insurance is the fifth most important service import and yet another sub-sector in which Canada has a deficit. Most of that deficit is the result of a deficit within the re-insurance sub-category for which Canada has relatively few exports but sizeable imports, as opposed to primary life and non-life insurance, which account for a large share of exports.

Figure 16

Commercial Service Exports and Imports by Service Type, 2016, $ Billions

Source: Statistics Canada, 2016

Figure 16 Text Alternative

Commercial Service Exports and Imports by Service Type, 2016, $ Billions

| Exports | Imports | |

|---|---|---|

| Management Services | 13,065 | 12,519 |

| Financial | 10,813 | 10,945 |

| Computer & Information | 7,398 | 4,477 |

| Technical | 6,974 | 6,008 |

| IP | 5,574 | 14,057 |

| R&D | 5,532 | 1,569 |

| Services to Business | 4,005 | 3,000 |

| Telecom | 2,390 | 2,009 |

| Audio-visual | 2,334 | 2,593 |

| Non-financial commissions | 2,189 | 1,037 |

| Maintenance & Repair | 2,098 | 1,122 |

| Insurance | 1,739 | 4,637 |

| Advertising | 1,511 | 850 |

| Construction | 698 | 466 |

| Equipment Rentals | 683 | 840 |

| Cultural & Rec. | 365 | 216 |

Trade balances may provide an indication of comparative advantage. Overall, Canada has a small surplus in commercial services comprising surpluses in 11 sub-sectors (indicated in blue). The largest surpluses are in R&D, computer and information services, non-financial commissions and services to business. Five subsectors had deficits in 2016 (indicated in red) with the largest in IP and insurance. The two sectors accounting for most trade - management and finance - are in surplus and in deficit respectively, but as a share of total trade are rather small and as such could largely be considered as being in balance.

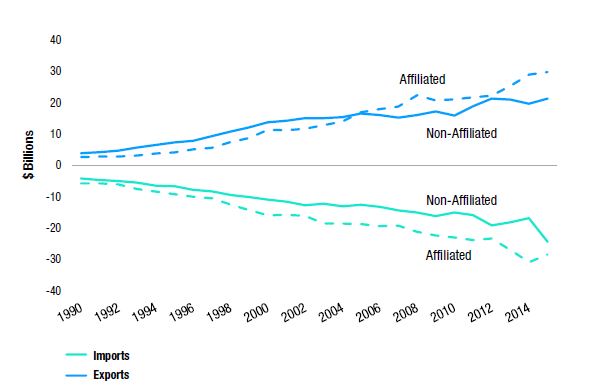

One feature that makes commercial services trade different from other types of trade in services is that a significant portion is intra-firm, that is, it takes place between parts of the same organization. The headquarters of a Canadian company, for example, may provide accounting services for an affiliate of that same company in a foreign country. This type of trade is considered affiliated trade, and is in contrast to non-affiliated trade that would occur if that same Canadian company provided accounting services to a company to which it was not related in a foreign country. Affiliated trade has been growing faster than non-affiliated trade for some time, and while for imports affiliated trade long since surpassed the non-affiliated kind, in 2005, affiliated exports surpassed non-affiliated exports for the first time. As of 2015, the year of the latest data available, affiliated exports of commercial services were 40 percent greater than non-affiliated exports.

Figure 17

Travel Exports by Business Type, 1990-2014, $ Billions

Source: Statistics Canada, 2016

Figure 17 Text Alternative

Travel Exports by Business Type, 1990-2014, $ Billions

| 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exports | Affiliated | 2,689 | 2,756 | 2,811 | 3,114 | 3,759 | 4,116 | 5,070 | 5,652 | 7,456 | 8,726 | 11,295 | 11,223 | 11,654 | 12,912 | 13,932 | 16,993 | 17,887 | 18,777 | 22,449 | 20,723 | 21,132 | 21,772 | 22,213 | 25,344 | 29,022 |

| Not | 3,864 | 4,163 | 4,784 | 5,683 | 6,576 | 7,318 | 7,830 | 9,253 | 10,804 | 12,098 | 13,811 | 14,203 | 15,150 | 15,151 | 15,415 | 16,536 | 16,107 | 15,263 | 16,078 | 17,285 | 15,974 | 18,843 | 21,345 | 20,999 | 19,753 | |

| Imports | Affiliated | -5,778 | -5,671 | -6,037 | -7,497 | -8,292 | -9,212 | -9,951 | -10,547 | -12,480 | -14,249 | -15,946 | -15,819 | -16,107 | -18,566 | -18,597 | -18,793 | -19,327 | -19,154 | -21,267 | -22,428 | -23,046 | -23,750 | -23,315 | -26,919 | -30,973 |

| Not | -4,100 | -4,652 | -4,983 | -5,552 | -6,555 | -6,611 | -7,807 | -8,295 | -9,374 | -10,068 | -10,923 | -11,567 | -12,680 | -12,172 | -13,130 | -12,527 | -13,192 | -14,387 | -15,008 | -16,153 | -15,039 | -15,908 | -19,088 | -18,160 | -16,777 |

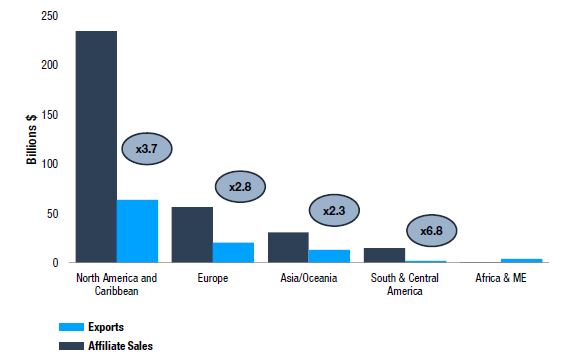

In addition to services trade taking place within the organizational structure of the firm as affiliated trade, the third mode of cross-border services trade involves a foreign company establishing a local subsidiary or branch in order to deliver the service. On the surface, these “sales by affiliates” look to be more important than service exports. In the case of North America, which is dominated by the United States but also includes financial centres in the Caribbean that host a large amount of Canadian direct investment abroad, especially in the financial sector, sales by service affiliates are 3.7 times as large as exports. For other regions, sales by service affiliates are almost as dominant at 2.8 times as large as exports for Europe and 2.3 times as large for Asia. Only in Africa are exports greater than sales by service affiliates.

Figure 18

Service Exports vs. Sales by Affiliates Abroad, 2015, $ Billions

Source: Statistics Canada, 2015

Figure 18 Text Alternative

Service Exports vs. Sales by Affiliates Abroad, 2015, $ Billions

| Affiliate Sales | Exports | |

|---|---|---|

| North America and Caribbean | 234,699 | 63,712 |

| Europe | 56,675 | 20,337 |

| Asia/Oceania | 30,944 | 13,175 |

| South & Central America | 14,923 | 2,198 |

| Africa & ME | 470 | 4,237 |

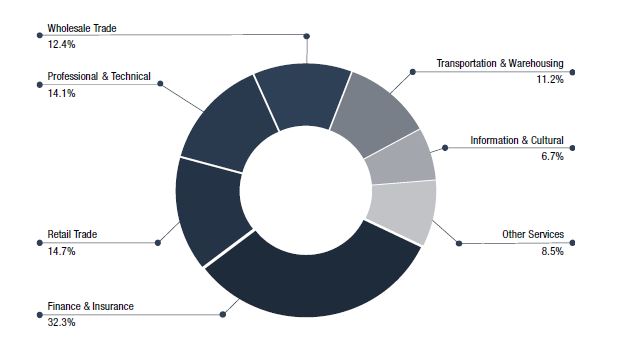

The figures on sales by affiliates must be interpreted with caution as they measure the value of sales by the industry of the affiliate, which in this case is in services, but it does not imply that they are comparable to service exports as have been described in this feature. Retail trade, for example, is the second most important sector while wholesale trade ranks fourth, with the two together accounting for 27.1 percent of sales. These sectors have no comparable category within commercial service exports and are most likely in fact involved in selling goods. For all sales by affiliates, there is additionally the potential to double-count when comparing them to exports. As noted, more than half of service exports are to affiliated companies, the value of which may be counted within sales figures. Sales by Canadian affiliates may also return to Canada in the form of imports.

Figure 19

Service Sales by Affiliates Abroad, 2015

Source: Statistics Canada, 2015

Figure 19 Text Alternative

Service Sales by Affiliates Abroad, 2015

| Finance and insurance [52] | 109,170 | 32.33% |

|---|---|---|

| Retail trade [44-45] | 49,685 | 14.71% |

| Professional, scientific and technical services [54] | 47,771 | 14.15% |

| Wholesale trade [41] | 41,722 | 12.35% |

| Transportation and warehousing [48-49] | 37,919 | 11.23% |

| Information and cultural industries [51] | 22,620 | 6.70% |

| Other services (3) | 28,823 | 8.53% |

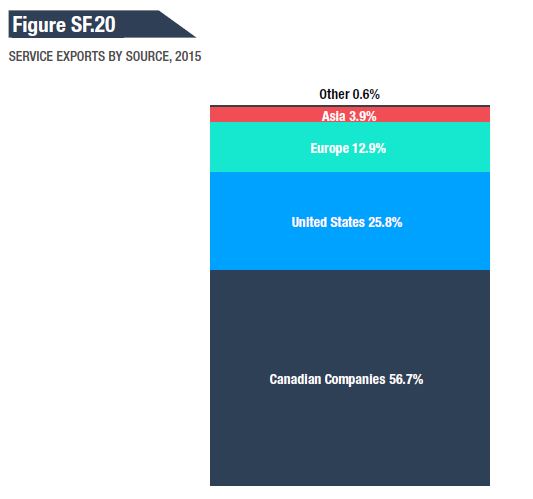

As a case in point, in addition to Canadian companies establishing affiliates abroad to reach foreign markets, foreign companies also establish affiliates within Canada, not only to reach the Canadian market but also to export. In fact, in 2015, 43.3 percent of Canadian commercial service exports were conducted by foreign companies in Canada; 25.8 percent of exports were by U.S. companies followed by 12.9 percent by European companies, and companies from other countries accounting for the remaining 4.5 percent.

Figure 20

Service Exports by Source, 2015

Source: Statistics Canada, 2015

Figure 20 Text Alternative

Service Exports by Source, 2015

| Service Exports by Source | ||

|---|---|---|

| Canadian | 37,286 | 56.7% |

| U.S. | 16,981 | 25.8% |

| Europe | 8,499 | 12.9% |

| Asia | 2,556 | 3.9% |

| ROW | 383 | 0.6% |

Measurement of Services Trade

It is sometimes claimed that services trade is not well measured. This perception likely comes from a comparison to trade in goods for which there is much more detail in terms of partners and products. Information about the goods trade is also timelier with statistics updated on a monthly basis. It may also be that people can imagine measuring a car crossing the border but have a more difficult time understanding how something non-tangible, such as exports of architectural services, could be well measured. Although there is room for improvement, there is no evidence of a systematic under-estimation of cross-border trade in services.

Information on trade in goods starts with customs documents: import and export declarations that contain detailed information on the good that is crossing the border. Statistics on the imports of goods are the gold standard given the incentive of customs officials to undertake inspections for security, duty collection, and other reasons. Statistics on services trade, on the other hand, are collected by survey.Footnote 21 Due to concerns about the burden put on survey responders and that surveys that are too long or complex will result in non-responses or incorrect information, it is only possible to undertake infrequent and relatively simple surveys. Increasingly, administrative data are used to supplement information sourced from surveys, allowing for surveys to become shorter and thus easier for respondents to complete while also improving data quality. While comparisons may be made between goods and services trade, goods trade is an exception; the methods used for measuring trade in services are comparable to those used to measure most other business and economic statistics including such core statistics as the calculation of GDP.

Measuring trade in services does have its own challenges. Unlike for goods, it is commonly understood that for services, exports may be measured more accurately than imports. This is the case because it is often easier to identify, and thus survey, the producer of the service than the consumer who may be more difficult to identify. Most architectural services, for example, will be delivered by architectural firms, while nearly any business or individual could potentially consume architectural services. One priority for the improvement of cross-border services trade statistics relates to digital trade and in particular the consumption of services by individuals through platforms such as Airbnb, Uber and Netflix, but also cloud computing services and software as a service.

Gathering more information by partner and by product is also a priority for improving services trade data, with a number of improvements made in recent years and reflected elsewhere in this feature. Increased use of administrative data, and other innovations, is allowing data to be presented for more trading partners, with increased detail on the type of services being traded, and in a more timely fashion, with further improvements expected going forward.

One of the most significant innovations in international trade analysis in recent years has been work based on the characteristics of exporters. This analysis has shown, for example, that relatively few exporters account for the vast majority of export value and that relatively few companies engage in exporting. The heterogeneous, or “new new”, theory of trade evolved from this work. Such data in most countries, including Canada, have been based only on goods trade. Comparable data on the characteristics of firms participating in trade in services would expand such analysis beyond the goods sector, which is a shrinking component of most economies. Negotiators of trade agreements face a unique challenge when it comes to services in that there are potentially four modes of supply that are addressed in trade agreements. Currently very limited data are available on mode of supply for services.

While service exports are no more poorly measured than most business or economic statistics, there is still room to improve. Statistical agencies recognize many of the concerns that are frequently raised with respect to services trade statistics and are actively working to improve the statistics on a number of fronts.

International Performance

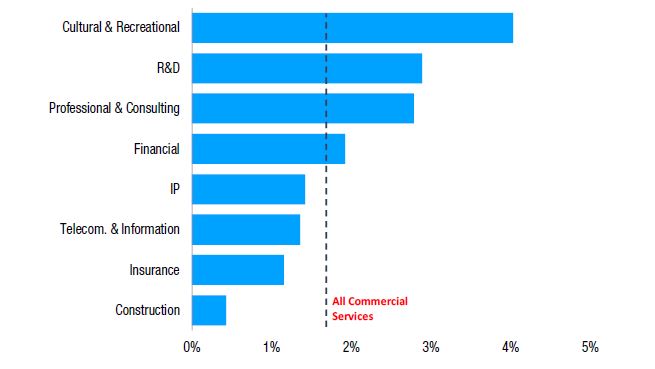

In 2017, Canada ranked as the 18th most important exporter of commercial services globally. At 1.6 percentFootnote 22 of global service exports, this ranks well below benchmarks such as Canada’s share of global output (2.0 percent)Footnote 23 and of merchandise trade (2.4 percent).Footnote 24 In 2017, the United States was the single largest exporter of services, followed by the United Kingdom – both well known for their services exporting prowess. The Netherlands, India, and Ireland all “punch above their weight” in services in terms of their share of service exports relative to their share of GDP. The Netherlands and Ireland are both top destinations for foreign direct investment (FDI); the former is also a top source for FDI. India is well known as a destination for the offshoring of business services. By contrast, Germany’s and Japan’s rankings for services are both well below their rankings for goods. China’s share of global services exports also ranks well below its share for goods, but does not rank poorly given its current level of development. Chapter 2 of the State of Trade gives more details on global services exports.

Figure 21

Canada’s Share of Global Commercial Service Exports

Source: WTO

Figure 21 Text Alternative

Canada’s Share of Global Commercial Service Exports

| Share | |

|---|---|

| Construction | 0.43% |

| Insurance | 1.16% |

| Telecom. & Information | 1.36% |

| IP | 1.42% |

| Financial | 1.92% |

| Professional & Consulting | 2.79% |

| R&D | 2.89% |

| Cultural & Recreational | 4.03% |

Canada has an above-average export share in cultural and recreational services, R&D, professional and consulting, and financial services. More detailed descriptions of these service categories are provided in the Commercial Services section of this report. International comparisons can be difficult: many countries do not report timely data for trade in commercial services or in some cases do not report services trade data at all. Furthermore, when data are reported, there can be important differences in how sub-sectors are defined. For these reasons, Canada’s competitiveness in commercial services is examined in two specific markets – the United States and the EU – which allows for the use of a single source of data for each market. The United States and the EU are the world’s two largest markets for commercial services and by far the most important destinations for Canadian commercial services.

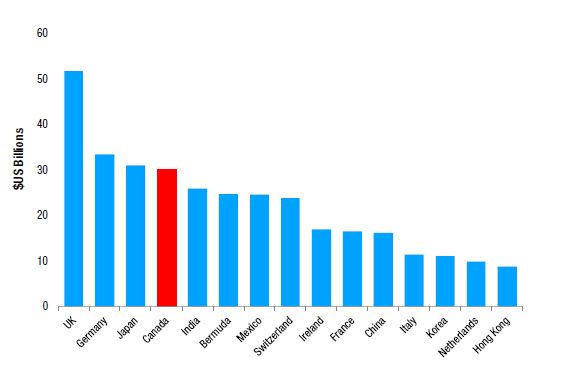

Canada in the U.S. Service Market

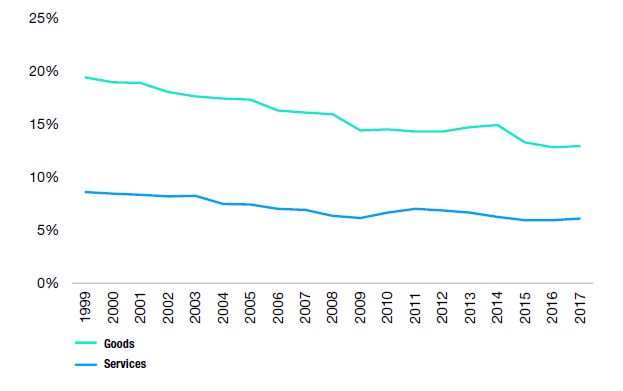

Canada’s share of U.S. service imports stood at 6.1 percent in 2017, well below Canada’s share of U.S. goods imports, which was 13.0 percent that year. Canada’s share of U.S. service imports is down from 8.4 percent in 2000, a decline of about one-quarter, but it is a smaller decline than was the case for goods, which fell by one-third. Canada is the fourth most important source of U.S. service imports, behind the United Kingdom, Germany and Japan, whereas for goods, Canada is second, behind China. U.S. service imports generally are much more diversified than for goods. In services, the top five countries account for 34.1 percent of imports, whereas for goods, the top five account for 58.8 percent of total imports. The United States is, by a wide measure, the most important destination for Canadian service exports.

Figure 22

Canada’s Share of U.S. Imports, 1999-2017

Source: Statistics Canada

Figure 22 Text Alternative

Canada’s Share of U.S. Imports, 1999-2017

| Goods | Services | |

|---|---|---|

| 1999 | 19.43% | 8.60% |

| 2000 | 18.96% | 8.44% |

| 2001 | 18.95% | 8.32% |

| 2002 | 18.05% | 8.18% |

| 2003 | 17.65% | 8.25% |

| 2004 | 17.45% | 7.49% |

| 2005 | 17.35% | 7.42% |

| 2006 | 16.30% | 7.01% |

| 2007 | 16.11% | 6.90% |

| 2008 | 15.98% | 6.35% |

| 2009 | 14.43% | 6.12% |

| 2010 | 14.53% | 6.68% |

| 2011 | 14.34% | 7.00% |

| 2012 | 14.32% | 6.89% |

| 2013 | 14.75% | 6.68% |

| 2014 | 14.92% | 6.27% |

| 2015 | 13.32% | 5.93% |

| 2016 | 12.84% | 5.93% |

| 2017 | 12.96% | 6.09% |

A commonly used technique for identifying in what sectors a country has comparative advantage is to use a measure of revealed comparative advantage. Using revealed comparative advantage measures is a challenge in services trade as the data are not always available, and categories of trade are not perfectly comparable across countries at a meaningful level of detail. As such, two simpler measures are used to identify where Canada may have a comparative advantage in services, and the analysis will focus on two specific partners: the United States and the European Union.

Simple trade balances are one potential indicator of comparative advantage. Where there is a surplus, by definition, there are more exports than imports (see “Balance” method reported in table). This method might be interpreted as measuring if Canada has an advantage vis-à-vis the United States (as opposed to having an advantage over other countries trading within the U.S. market). Overall, Canada has a sizeable trade deficit with the United States in services trade reflecting U.S. strength in services. By this measure, expressed in the table as a percentage of bilateral trade, Canada has surpluses in only four sectors: R&D services, “other” technical services, accounting, and computer services. Canada’s overall deficit in services, expressed as a share of bilateral trade, is 28.6 percent. If this is used as a baseline, there are another five sectors where Canada’s deficit is below 28.6 percent and thus may be thought of as having a weak comparative advantage.

Figure 23

U.S. Top Sources of Service Imports, $ Billions

Source: Statistics Canada

Figure 23 Text Alternative

U.S. Top Sources of Service Imports, $ Billions

| 2016 | |

|---|---|

| Hong Kong | 8,748 |

| Netherlands | 9,794 |

| Korea | 10,974 |

| Italy | 11,339 |

| China | 16,139 |

| France | 16,451 |

| Ireland | 16,917 |

| Switzerland | 23,763 |

| Mexico | 24,569 |

| Bermuda | 24,629 |

| India | 25,808 |

| Canada | 29,950 |

| Japan | 31,004 |

| Germany | 33,395 |

| UK | 51,698 |

A second measure of comparative advantage is similar to traditional measures of revealed comparative advantage and uses Canada’s overall share in services in U.S. imports as a baseline. Those sectors in which the share exceeds this baseline might be said to have a comparative advantage (see “Import Share” method in table). This method may be best thought of as assessing if Canada has an advantage compared to other (i.e. third) countries in the U.S. market. By this measure, Canada has an advantage in 12 sectors - including all but one of the sectors identified using the “balance” method.

| Balance | Import Share | |

|---|---|---|

| Advertising | -85.3 | 0.6 |

| Education | -73.1 | -3.7 |

| Intellectual Property | -70.5 | -2.8 |

| Leasing | -70.1 | -2.0 |

| Legal | -65.6 | 1.1 |

| Insurance | -59.2 | -4.9 |

| Financial Services | -52.3 | 1.9 |

| Information | -51.2 | 1.4 |

| Industrial Engineering | -42.0 | -2.3 |

| Construction | -28.1 | 1.5 |

| Architectural | -27.8 | 1.3 |

| Telecom | -26.4 | 0.0 |

| Maintenance & Repair | -17.2 | 10.7 |

| Business & Consulting | -6.9 | 1.0 |

| Computer | 21.5 | 5.3 |

| Accounting | 34.1 | 6.3 |

| Other Technical | 44.2 | 8.7 |

| Research and Development | 67.6 | 0.0 |

Balance: Canada’s surplus (deficit) with U.S. as % of total trade

Import Share: Percentage points by which import share is greater (less) than import share of total services

Source: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis

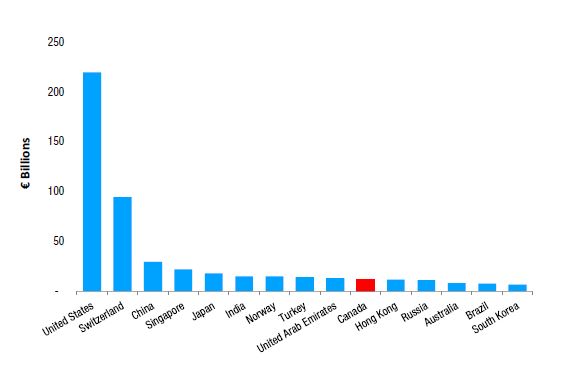

Canada in the EU Service Market

Unlike in the United States, where Canada’s share of goods imports is significantly larger than that for services, Canada’s share of both EU service and goods imports amounted to 1.7 percent in 2016. Also unlike in the United States, where Canada’s share of both goods and services has been on the decline, Canada’s share of EU services imports has been gradually decreasing, from 2.2 percent in 2010, while the share of goods imports has remained steady over the same time period.Footnote 25 In 2016, Canada was the tenth most important source of EU service imports (excluding intra-EU trade). The United States stands out as by far the largest source of external EU imports of services. As a rough benchmark, the Canadian economy is about one-tenth the size of the U.S. economy; however, EU imports from the United States are more than 18 times as great as those from Canada indicating the relatively strong performance of the United States in services. Switzerland also stands out for its large share of EU service imports, but given it unique location surrounded by EU countries and long history of strength in financial services, it is not as useful to make comparisons with Canada. In terms of diversification of sources, EU service imports are slightly less diverse than goods imports; the top five countries account for 53.8 percent of total service imports, whereas the top five account for 52.7 percent for total goods imports.

Figure 24

EU Top Sources of Service Imports, 2016, € Billions

Source: Eurostat, 2016

Figure 24 Text Alternative

EU Top Sources of Service Imports, 2016, € Billions

| United States | 219.3 |

|---|---|

| Switzerland | 94.1 |

| China | 29.6 |

| Singapore | 22.0 |

| Japan | 18.0 |

| India | 15.3 |

| Norway | 15.2 |

| Türkiye | 13.9 |

| United Arab Emirates | 13.2 |

| Canada | 11.8 |

| Hong Kong | 11.4 |

| Russia | 11.3 |

| Australia | 8.3 |

| Brazil | 7.9 |

| South Korea | 6.6 |

As noted, Canada’s share of EU service imports has fallen considerably over the past six years for which comparable data are available. Business services is by far the largest sub-sector for EU imports overall as well as for EU imports from Canada and as such was also responsible for most of the fall in Canada’s share of EU imports. EU imports from Canada in this sector actually increased modestly between 2010 and 2016 (up 16.7 percent), but could not keep pace with the growth in overall EU imports (up 95.8 percent).

Employing similar techniques as were used to examine Canada’s comparative advantages in the U.S. services import market produces rather striking results for the EU.Footnote 26 As was the case with the United States, the trade balance approach indicates far fewer sectors of possible comparative advantage (at only six sectors) than does the import share approach. Overall, Canada had a services trade deficit of €6.7 billion with the EU in 2016, €3.5 billion of which is in commercial services representing 23.9 percent of two-way trade. Using 23.9 percent as a new benchmark for comparative advantage, rather than being limited to those sectors with a surplus, adds an additional four sectors and greatly increases the overlap with the results for the United States. Most notable in the EU case, however, is the close correlation between the trade balance and import share approaches. There is a strong correlation between trade balance and import share when ranked. These measures of comparative advantage point in a broadly similar direction as the results for the United States in that: 1) R&D stands out as a sector in which Canada performs well; 2) Canada broadly shows the signs of having advantages in professional and technical services; and, 3) some sectors show Canada’s market-specific strengths, with education being an example in the EU while Canada’s performance in education in the U.S. market ranked poorly.

| Balance | Import Share | |

|---|---|---|

| Construction | -78.4 | -0.3 |

| Architecture | -78.4 | -0.7 |

| Health Services | -77.8 | -1.0 |

| Operating Leasing Services | -72.7 | -0.6 |

| Waste Treatment | -72.0 | -0.9 |

| Financial Services | -66.7 | -0.5 |

| Heritage and Recreation | -65.5 | -0.9 |

| Intellectual Property | -63.0 | -0.9 |

| Information | -54.1 | 0.4 |

| Engineering | -50.2 | 0.6 |

| Insurance | -47.4 | 0.0 |

| Legal | -44.3 | 0.4 |

| Telecom | -40.8 | 0.1 |

| Computer | -33.2 | 1.4 |

| Other Business Services | -21.4 | 0.1 |

| Accounting | -21.2 | 0.6 |

| Scientific and other Technical | -15.7 | -0.3 |

| Education | -13.2 | 1.3 |

| Other Personal Services | 9.9 | 0.0 |

| Business and Management | 11.8 | 0.7 |

| Research and Development | 34.9 | 0.1 |

| Advertising | 37.2 | 0.4 |

| Trade-related Services | 55.2 | 0.2 |

| Audiovisual | 62.4 | 9.1 |

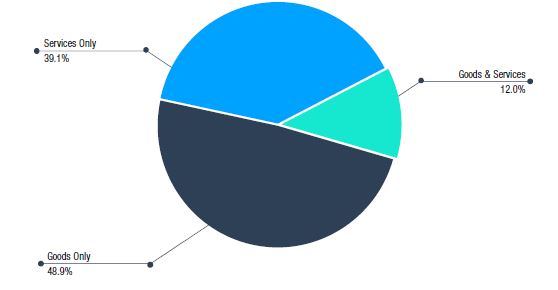

SME Exporters of Services

Data on the characteristics of the firms that export and import merchandise come from customs documents. These data inform us that while most exporters are small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs),Footnote 27 most of the value of exports comes from large firms. Even among SMEs, a relatively small share of exporters contributes most of the value. Only much more limited data from surveys are available for exporters of services.

As of 2014, an estimated 11.8 percent of SMEs exported. According to the Survey of SME financing and growth, in 2011, the year of the most recent data available,Footnote 28 48.9 percent of exporting SMEs exported goods only, 39.1 percent exported services only, and 12.0 percent exported both goods and services. As a share of the number of firms, however, the share that exports in the services sector is well below that in goods. This finding is not unique to Canada: even in the United States, which is often thought to have a comparative advantage in services, service firms’ export participation lags manufacturing firms by a considerable margin.Footnote 29

Figure 25

SME Exporters – Goods vs. Services, 2011

Source: Survey of SME Financing and Growth, 2011

Figure 25 Text Alternative

SME Exporters – Goods vs. Services, 2011

| share, % | |

|---|---|

| Goods Only | 48.9 |

| Services Only | 39.1 |

| Goods & Services | 12.0 |

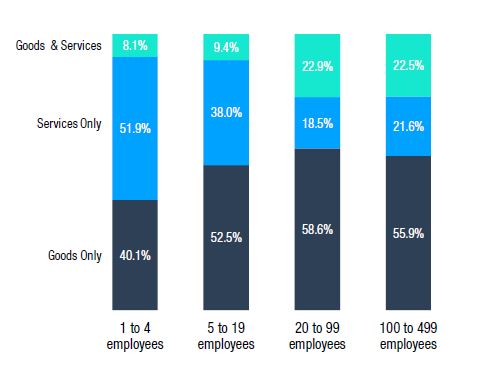

The smallest of SMEs, those with between one and four employees, are the most likely to be services exporters. Some 51.9 percent of these “micro-SMEs” export only services and another 8.1 percent export both goods and services. By comparison, the largest SMEs, those with between 100 to 499 employees (the “mediumsized enterprises” in SME), are less likely to export services overall, and when they do only 21.6 percent export services only but a larger percentage, 22.5 percent, export both goods and services. There are a number of reasons for the different propensity of firms to export services according to their size. The most likely reason is that there may be less scope for economies of scale in the production of services. Large manufacturing plants achieve economies of scale through specialization of tasks such as on an assembly line. It is not clear that the same scope for specialization of tasks and standardization of outputs is possible in services. Tasks in manufacturing also benefit from proximity, for example, minimizing the distance between tasks as a good travels down an assembly line yields savings. With the advent of just-in-time delivery of inputs, suppliers are, in many cases, located in close proximity to the customer. For many service industries the benefits of such proximity are not as clear. Finally, goods-producing industries are often capital intensive and greater scale allows for better access to financing enabling businesses to make expensive capital outlays. By the same token, where size confers less benefit, such as in services, this lowering of barriers to entry may permit new, smaller, companies to enter the market. But it is not always the case that service firms are smaller. Six of the ten most valuable Fortune 500 companies are in the services sector. Financial services have always ranked highly on such company lists and have recently been joined by technology companies.

Figure 26

SME Exporters by Size of Firm, 2011

Source: Statistics Canada, Survey of SME Financing and Growth, 2011

Figure 26 Text Alternative

SME Exporters by Size of Firm, 2011

| Goods, % | Services, % | Both, % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 to 4 employees | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.1 |

| 5 to 19 employees | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.1 |

| 20 to 99 employees | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| 100 to 499 employees | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

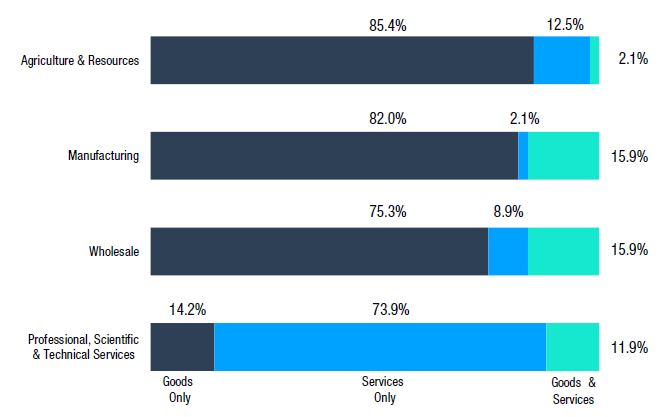

Among industries, goods-producing industries are, not surprisingly, focused on exporting goods; 82.0 percent of SMEs in manufacturing export only goods, while 85.4 percent of SMEs in the agriculture and resources sectors export only goods. There are notable differences though; 12.5 percent of SMEs in the agriculture and resources sectors export only services while only 2.1 percent export both goods and services, indicating a clear distinction between those that produce and export the goods and those that provide services in the sector. By comparison, only 2.1 percent of manufacturing SMEs export only services, but 15.9 percent report exporting both goods and services. This likely reflects the linkage between manufacturing a product and providing follow-up services (see section on servicification in this report). In the professional, scientific and technical service sector, 73.9 percent of SMEs report exporting only services compared to 14.2 percent for only goods and 11.9 percent for both goods and services.

Figure 27

SME Exporters by Select Industry, 2011

Source: Survey of SME Financing and Growth, 2011

Figure 27 Text Alternative

SME Exporters by Select Industry, 2011

| Goods | Services | Both | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Professional, Scientific & Technical Services | 0.1 | 0.7 | 0.1 |

| Wholesale | 0.8 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| Manufacturing | 0.8 | 0.0 | 0.2 |

| Agriculture & Resources | 0.9 | 0.1 | 0.0 |

Although service firms tend not to have the same economies of scale as producers of goods, they do appear to benefit from a different type of economy of proximity – clustering. Goods-producing industries are more likely to be located outside of major metropolitan areas. That may be driven by the location of natural resources as is the case with mining, forestry and agriculture, or of inexpensive land for large manufacturing plants. The idea of the “company town” where one large company was the dominant employer in town is largely associated with goods-producing companies. Services-producers, on the other hand, and knowledge-based services in particular, are largely urban affairs and appear to benefit from proximity to firms in a similar line of business. Some 39.0 percent of rural SMEs export services compared to 53.5 percent of urban SMEs.

Figure 28

Majority Female-Owned SMEs Exporters by Industry, 2014

Source: Statistics Canada, Survey of SME Financing and Growth, 2014

Figure 28 Text Alternative

Majority Female-Owned SMEs Exporters by Industry, 2014

| share, % | |

|---|---|

| Other Services | 4.5 |

| Transportation & Warehousing | 7.8 |

| Wholesale Trade | 7.8 |

| Accommodation & Food Services | 11.2 |

| Retail Trade | 12.8 |

| Manufacturing | 16.0 |

| Health, Information, & Arts | 16.4 |

| Professional & Technical Services | 20.4 |

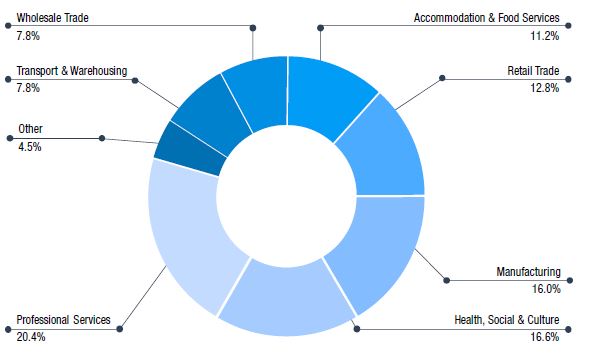

An additional notable characteristic of SMEs that export services is that they are more likely to be female-owned than SMEs that export goods: 8.7 percent of SMEs that export services are majority female-owned compared to 7.5 percent of goods exporters. But, far fewer export goods and services: only 2.7 percent of SMEs that export both goods and services are majority female-owned. This is likely related to size as female-owned SMEs tend to be smaller while those SMEs that export both goods and services tend to be larger. The importance of services for female-owned SMEs is also apparent when looking at sub-sector composition. While majority male-owned SMEs are dominated by manufacturing, among female-owned SMEs professional services is the most important sub-sector followed by health, social and culture, with manufacturing ranking only third.

SME exporters in the service sector face challenges that are common to the goods-exporting sector as well as unique challenges. Distance to customers ranks as the most important obstacle for both small and mediumsized exporters and is also ranked as a more important obstacle for service-exporters than for goods exporters. This may reflect the fact that, face-to-face meetings are still important in the service sector and may require travel, despite technology that allows for easier and less costly communications. It is notable that border security is the third-ranked obstacle and is also rated as more important for service exporting SMEs than for goods exporting SMEs. For goods exporters, security may mean scans of containers crossing the border while for service exporters it means longer line-ups and more intrusive scans for people crossing the border. Of note, financing issues are not ranked highly for either goods or service exporters. Similarly, intellectual property rights protection is not rated as a major concern for SMEs exporting either goods or services. The aggregate figures, however, can hide a significant degree of detail due to the size and diversity of the service sector: some survey respondents in certain sub-sectors may rate an obstacle highly even if the majority do not. The characteristics of the sector as well as the predominant mode of delivery for exports in each sector are often important factors in predicting if an obstacle will be rated as significant.

Relative to other service industries, small firms involved in transportation (especially air and ground transportation) find legal and administrative obstacles to be of high importance as a barriers to export.Footnote 30 Similarly, border security is identified by small firms as a high concern in transportation (truck and air transport as well as warehousing). In both cases, this is likely due to the frequency of cross-border dealings for this industry. On the other hand, service firms of medium size involved in scientific technical services and laboratory testing rated concerns about border security highly; this is likely due to the sensitivity of work that is being done. Distance to customers was reported of high importance, mainly by small architectural, engineering and related services firms. This makes sense as these firms may require the movement of people to perform their work. The industries that most identified linguistic and cultural issues as obstacles to exporting their services were those that provide services with a strong language or cultural awareness component: advertising, software publishing, online publishing, and information and cultural industries.

| Small Enterprises (%) | Medium Enterprises (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manufacturing Exporter | Service Exporter | Manufacturing Exporter | Service Exporter | |

| Distance to customers | 25.0 | 38.3 | 21.2 | 36.6 |

| Meeting customers cost requirements | 37.6 | 31.1 | 39.7 | 11.3 |

| Border security issues | 16.6 | 27.2 | 10.2 | 27.7 |

| Meeting customers quality requirements | 21.1 | 25.1 | 23.8 | 3.4 |

| Canadian export taxes or trade obstacles | 18.1 | 15.6 | 16.3 | 14.6 |

| Canadian legal/administrative obstacles | 15.6 | 15.3 | 10.6 | 25.9 |

| Access to financing | 19.3 | 15.0 | 14.6 | 18.0 |

| Foreign tariffs or trade barriers | 21.3 | 14.4 | 21.6 | 16.9 |

| Uncertainty of international standards | 18.7 | 14.1 | 16.5 | 14.5 |

| Linguistic or cultural obstacles | 8.7 | 10.7 | 10.1 | 2.8 |

| Intellectual Property (IP) right violation concern | 9.5 | 6.5 | 11.9 | 15.7 |

| Customer requirements to use specific technologies | 13.8 | 6.4 | 7.8 | 0.0 |

Conclusions