Evaluation of the Canadian Technology Accelerator Program 2016-17 to 2020-21

Evaluation Report

Prepared by the Evaluation Division (PRA)

Global Affairs Canada

March 2023

Table of contents

- Acronyms and abbreviations

- Executive summary

- Program background

- Evaluation scope and methodology

- Findings

- Conclusions

- Recommendations

- Considerations

- Annex

Acronyms and abbreviations

- BAIs

- Business accelerators and incubators

- B2B

- Business to business

- BBA

- High Intensity Services Division, located at Headquarters (HQ)

- BIPOC

- Black, Indigenous, People of Colour

- BTB

- TCS Tools, Analysis and Performance Division

- CTA

- Canadian Technology Accelerator

- CTA HQ

- CTA coordinating team located in the BBA division at HQ

- CTA mission

- Mission/trade office abroad where a CTA program is active with a full-time employee (FTE) funded by the CTA Program

- CTA network

- All GAC employees who support and deliver the CTA Program

- EOF

- Economic outcome facilitated

- EDI

- Equity, diversity and inclusion

- FY

- Fiscal year

- GAC

- Global Affairs Canada

- GBA Plus

- Gender-based analysis plus

- HQ

- Headquarters

- ICT

- Information and communication technologies

- KPI

- Key performance indicator

- OGDs

- Other government departments

- RO

- Regional office

- SME

- Small- and medium-sized enterprises

- SOP

- Standard operating procedure

- TC

- Trade commissioner

- TCS

- Trade Commissioner Service

Executive summary

This evaluation examined Global Affairs Canada’s Canadian Technology Accelerator (CTA) programs across 12 missions abroad for the period 2016-17 to 2020-21. The objectives of the evaluation were to determine the extent to which the programming is relevant, efficient and effective at supporting the growth of Canadian small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) by providing access to unique resources and support within key global technology clusters. This report presents the evaluation findings, conclusions, recommendations and considerations to support decision-making for program improvements.

The CTA programs are relevant and responsive in meeting the needs of the SMEs served. CTA programs generally exceed targets for services delivered and are often repeated to meet demand from multiple cohorts of Canadian companies. Initiatives are flexible, adaptable and able to provide the breadth of supports sought by SMEs. The mixed model of delivery (virtual and in-person) that resulted from the need to pivot service delivery during the COVID-19 pandemic has proven to be more responsive and more efficient, increasing accessibility to programming. CTA programs are distinct from other services in the business accelerator and incubator (BAI) ecosystem, providing specialized sector expertise, extensive in-country contacts and hands-on guided service that delivers unique value to Canadian companies.

Recruitment processes were seen to be fair, and there were CTA programs designed and targeted to women as an underrepresented group. The Program is still maturing its gender-based analysis plus (GBA Plus) strategy and approaches. The application of an equity, diversity and inclusion (EDI) lens in program design and delivery was encouraged, but there were areas for improvement, such as more standardization of approaches and disaggregated data collection.

The Program saw meaningful improvements in its administration and coordination activities over the evaluation period. Detailed standard operating procedures (SOP) were developed and played a large role in clarifying roles and responsibilities, accounting for decision-making authorities, facilitating coordination of communications and enhancing joint planning across the CTA Program. However, there were opportunities for continuous improvement in enhancing coordination of programming and recruitment activities across missions, increasing the level of transparent feedback to unsuccessful applicants, and better leveraging the involvement of Canadian regional trade commissioners (TC).

The evaluation found many encouraging examples of short-, medium- and long-term outcomes and economic impacts. CTA client firms are increasing their client base and networks, expanding operations in a foreign market, increasing revenues, creating jobs at home and abroad and increasing capital investment.

However, performance monitoring is cumbersome and available data does not generate consistent and accurate information.

Summary of recommendations

- Management of the International Business Development, Investment and Innovation (BFM) Branch should improve its capacity to measure impact and collect evidence in order to assess and demonstrate how it fulfills market demands.

- Management of BFM Branch should fine-tune its outreach approach and assess its results in participant reach.

- Management of BFM Branch should enhance program coherence by establishing a cohesive program calendar and more even level of involvement of all regional offices.

Program Background

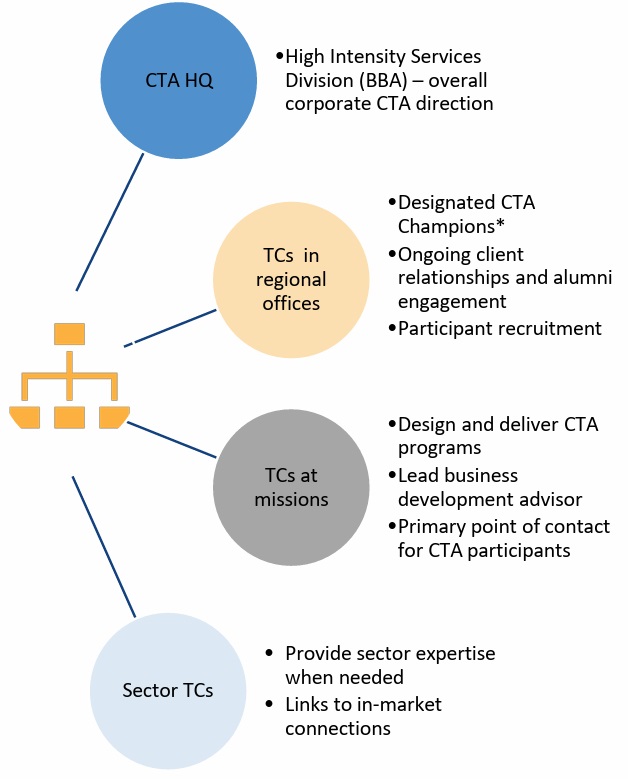

Figure 1

* A CTA Champion is a Trade Commissioner representing the CTA in Canadian Regional Offices

Text version

CTA HQ

- High Intensity Services Division (BBA) – overall corporate CTA direction

TCs in regional offices

- Designated CTA Champions*

- Ongoing client relationships and alumni engagement

- Participant recruitment

TCs at Missions

- Design and deliver CTA programs

- Lead business development advisor

- Primary point of contact for CTA participants

Sector TCs

- Provide sector expertise when needed

- Links to in-market connections

* A CTA Champion is a Trade Commissioner representing the CTA in Canadian Regional Offices

The Global Affairs Canada (GAC) Canadian Technology Accelerator (CTA) Program was introduced to help high-potential Canadian SMEs undertake international expansion.

The CTA Program is a global business development program delivered by GAC’s Trade Commissioner Service (TCS). In 2009, the CTA Program began as a pilot initiative at the Canadian consulate general in San Francisco and Palo Alto, California. The CTA programs are designed to help high-potential Canadian SMEs with an existing technology, product or service explore growth opportunities in key global technology hubs. CTA programs help participants maximize their exposure and time in international markets and provide them with relevant and impactful business supports. The CTA programs aim to support the growth of Canadian SMEs through customized services that help businesses overcome barriers in order to take advantage of opportunities in international markets.

Companies that participate in the CTA are recruited across Canada. Firms apply to be part of CTA programs and are selected through a competitive process, under which the Trade Commissioner Services (TSC) and a panel of industry experts review applications and decide whether applicants are eligible and a good fit for a given location. The evaluation process assesses team experience, product-market fit, marketplace traction and potential to scale.

The GAC CTA Program is overseen centrally but is delivered by missions internationally in collaboration with Canadian regional offices (RO).

The overall CTA Program is managed by the High Intensity Services Division (BBA) within the Trade Commissioner Service. BBA approves funding requests and ensures consistency across missions that deliver CTA programs. International missions design time-bound CTA programs based on the conditions of the local market and/or region they cover. Once the planned activities are approved by BBA, missions recruit participating firms, manage the application process and organize activities with SME cohorts. Canadian ROs support the identification of potential CTA firms, and support program promotion and recruitment.

The CTA Program is now delivered using a hybrid model

In fiscal year (FY) 2019-20, the COVID-19 global pandemic directly affected the Program, necessitating a pivot to online delivery. The Program is currently implementing a hybrid model where some activities take place virtually and others take place in-person.

Time-bound, cohort-based, sector-specific CTA programs are run by 12 missions internationally.

The CTA programs target Canadian companies in the information and communication technologies (ICT), life sciences and clean tech sectors, to assist them in scaling-up an existing technology, product or service in global technology markets outside of Canada. A CTA program delivered by a mission typically lasts three to eight months. A cohort usually consists of 6 to 12 companies at a similar stage of development, and from the same sector.

From FY 2016-17 to 2020-21, a total of 607 firms participated in at least one CTA program.

The majority of those firms were based in Ontario (42%), Quebec (19%) and British Columbia (17%). Most participating firms were in information and communications technologies or digital industries, while about a quarter were from life sciences and clean tech.

A CTA program’s activities included, for example: an onboarding session; market intelligence sessions; one-on-one calls with a trade commissioner (TC), mentor, or advisor; meetings with sector experts and potential partners, clients, investors or venture capitalists; panels and workshops on market dynamics and business strategy; demo days or pitch sessions; and an off-boarding session. In some cases, short-term pre-CTA programs were also offered, ranging from between 48 hours and 1 week in duration, with the aim of preparing companies for the full CTA program or assessing the demand for a program in a new sector.

The CTA Program was expanded in FY 2019-20.

From 2017 to 2020, the majority of CTA program delivery (85%) took place in the United States. In 2019, the CTA Program expanded to Hong Kong, Japan (Tokyo), Singapore and Taiwan (Taipei), and in 2020 it expanded further to Mexico (Mexico City), the United Kingdom (London), Germany (Berlin) and India (Delhi).

Figure 2: International Missions delivering CTA programming

Text version

World map outlining the 12 cities where CTA program was delivered:

- San Francisco

- Silicon Valley

- Mexico City

- Boston/Cambridge

- New York City

- London

- Berlin

- Delhi

- Singapore

- Hong Kong

- Taipei

- Tokyo

CTA Program expenditures (FY 2016-17 to 2020-21)

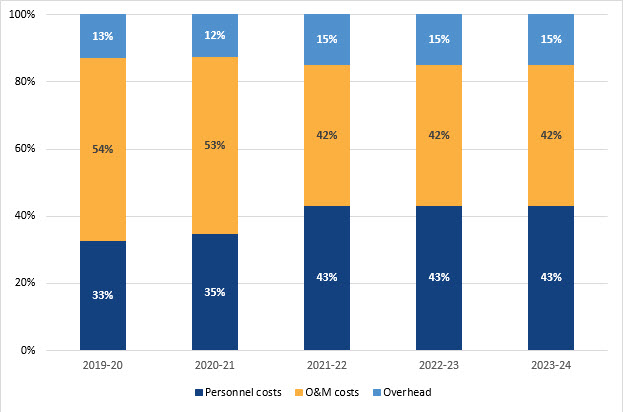

The CTA Program is an operational program, not a grants and contributions program. The main budget allocation is almost equally split between personnel and operations and maintenance costs.

Figure 3: CTA expansion costing, FY 2019-20 to 2023-24

Text version

| Year | Overhead | O&M costs | Personnel |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2019-20 | 13 % | 54 % | 33 % |

| 2020-21 | 12 % | 53 % | 35 % |

| 2021-22 | 15 % | 42 % | 43 % |

| 2022-23 | 15 % | 42 % | 43 % |

| 2023-24 | 15 % | 42 % | 43 % |

CTA Program resources

Following Treasury Board approval of the Program in 2013, the Program received $5 million over 3 years, to March 2016. Following a program evaluation completed in 2015, Treasury Board renewed funding in 2016 for 2 years at $2 million per year. In 2017, the CTA received $10 million over 5 years starting in FY 2018-19 and $2 million ongoing, making it a permanent program for the USA. In 2018, CTA expanded to Asia with $7.4 million over 5 years, also starting in FY 2018-19, and $1.6 million starting in the following fiscal year. The 2018 Fall Economic StatementFootnote 1 included a commitment to also expand the CTA Program (with new funding of $17 million over 5 years to FY 2023-24, and then $3.8 million ongoing) in global technology hubs outside of the USA and Asia. As of FY 2019-20, CTA expanded from 8 to 12 technology hubs to align with Canada’s Export Diversification StrategyFootnote 2.

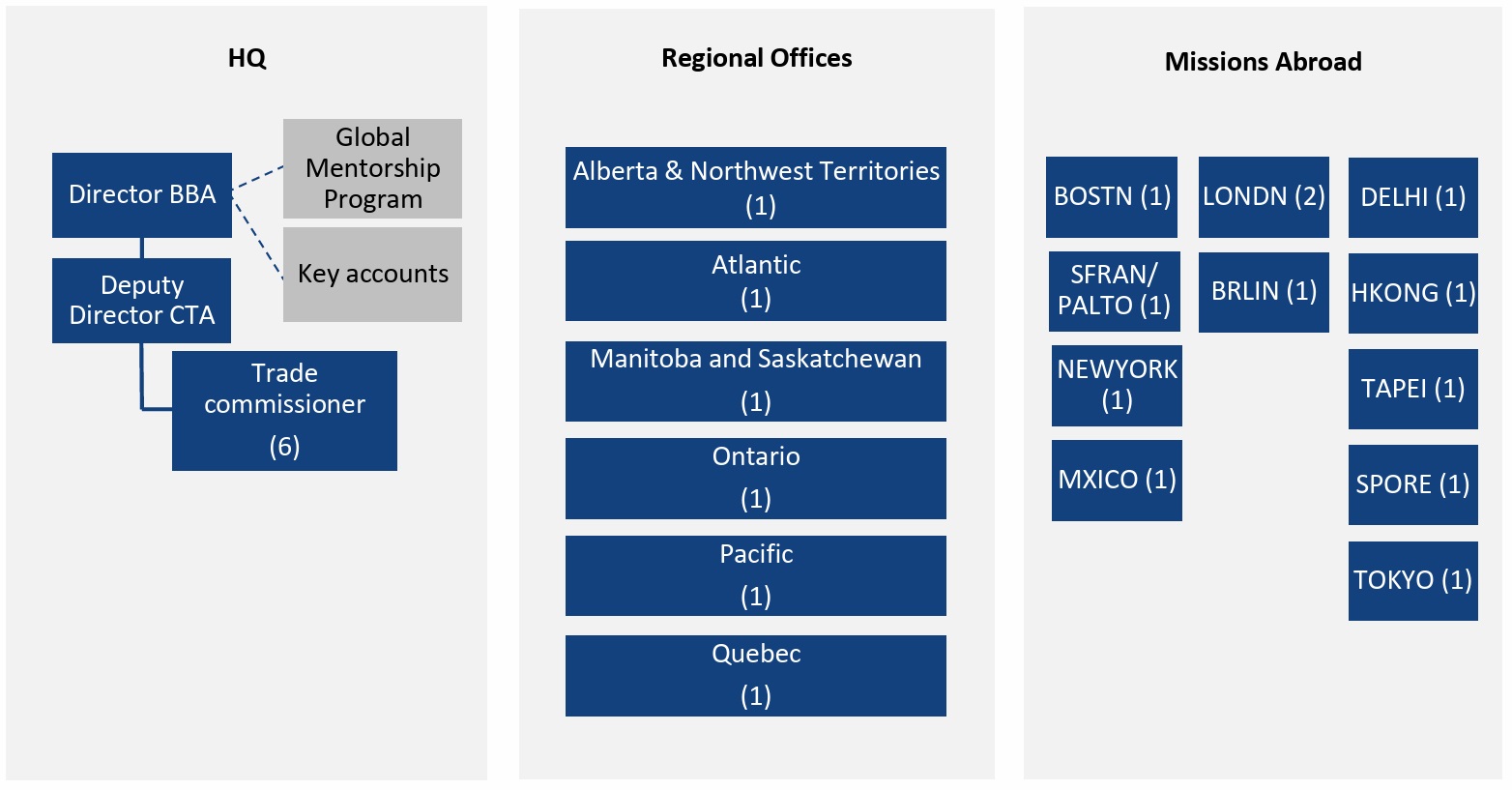

Figure 4: Map of CTA FTEs at headquarters, missions and regional offices (2022)

Text version

Organigramme outlining headquarters, regional offices and missions abroad.

Evaluation scope and methodology

Evaluation scope and objectives

Evaluation objective

The evaluation sought to determine the extent to which the CTA Program is relevant, efficient and effective in supporting the growth of Canadian SMEs by providing them with access to unique resources and support within key global technology clusters.

Evaluation approach

The evaluation was conducted using a hybrid approach, with responsibilities shared between an external independent consulting firm and the Evaluation Division (PRA).

The evaluation design was based on consultations with key CTA Program stakeholders at GAC headquarters, missions abroad, and ROs; a review of key Program documents; and a preliminary literature review to identify approaches to assess performance of business accelerators and incubators.

Evaluation scope

The evaluation covered the 5-year period from FY 2016-17 to 2020-21. It focused on relevance, effectiveness and efficiency criteria, and assessed how the CTA Program responded to the needs of Canadian SMEs: its alignment with policies on inclusive trade and equity, diversity and inclusion; its progress towards stated objectives; how it was designed for effective management; its administration and delivery; and the extent to which it had leveraged opportunities for synergies with other trade programs in the innovation space.

The evaluation assessed, through five core questions, the work of BBA, BBR (the former Aerospace, Automotive, Defence and ICT Practices Division, which managed the CTA until 2019), regional offices and the participating missions, and the short, intermediate and long-term outcomes as per the Program’s logic model (Annex).

A key focus of the evaluation was to apply a differentiated approach to looking at results and impacts. The evaluation is more summative in nature for the CTA programs delivered in the United States, focusing more on immediate and intermediate outcomes. Acknowledging that other global missions are still in an early stage of implementation, the evaluation used a more formative approach for these locations and focused more on process implementation. The evaluation provides evidence-based findings to support decision-making with regards to continuous improvement.

Related evaluations

The CTA Program was previously evaluated in 2015, which resulted in six recommendations: the need for a more refined and defined selection and recruitment process; common minimum requirements and standards across missions; alignment of resources to ensure optimal TC-to-company ratios; leveraging the entire TCS network and improving communication with ROs and non-CTA missions; a single web presence to improve communication; and improved reporting and recording of CTA outputs and outcomes. The management response and action plan (MRAP) prepared by the Program noted progress in several of the areas and acknowledged that these were important areas for ongoing improvement. The Program committed to a number of actions in response to the recommendations, including, for example, its intent to ensure consolidated and consistent data collection and storage for long-term analysis and reporting by March 2017.

The Office of the Chief Economist of Global Affairs Canada is undertaking an econometrics analysis of firm level data from Statistics Canada, which will provide a measure of the impact of the CTA program on firm performance to complement the evaluation.

Evaluation questions

| Questions | Criteria |

|---|---|

| Q1. To what extent is CTA programming relevant to, and distinctly meeting the needs of, Canadian tech SMEs? | Responsiveness and relevance |

| Q2. In what ways has the CTA Program provided support to businesses owned and operated by underrepresented groups (i.e. women, Indigenous, youth, or others)? | Effectiveness |

| Q3. To what extent is the Program managed and administered in an efficient manner? | Efficiency |

| Q4. To what extent has the CTA Program contributed to long-term outcomes for the CTA-USA, and to short and medium-term outcomes for the Global Hub pilot? | Effectiveness |

| Q5. What lessons have been learned from the implementation of the CTA Global Hub pilot? | Effectiveness |

Methodology

The evaluation used a mixed-methods approach, where data were collected from a range of sources to ensure multiple lines of evidence when analyzing data and formulating findings. While examples are used for illustrative purposes, each finding was triangulated using evidence from a mix of quantitative and qualitative data. Three main methods were applied to conduct this evaluation:

Document and data review

Review of internal GAC documents:

- presentations and planning meeting notes

- results from the TCS client satisfaction survey

- programming evaluation criteria, assessment forms and tools

- standard operating procedure (SOP) manual and how-to-guides

- financial data

- TRIO data

- a meta-synthesis of 39 Strategia reports

Interviews

Semi-structured individual key informant interviews (N=44) were conducted with a variety of internal stakeholders at GAC, with external stakeholders in other government departments (OGDs), and with other business accelerators and incubators (BAIs).

This included CTA HQ and other GAC staff (N=10); TCs at ROs (N=9) and TCs at missions (N=17); OGDs (N=4); and other BAIs (N=4).

Case studies

Five case studies were purposefully sampled across the evaluation time period across the following criteria:

- four mission locations (United States, Germany, Mexico, Japan)

- four sectors (clean technology, auto technology, agriculture and processed foods, and information and communications technology)

- number of CTA services received (ranging from 4 to 68)

The case studies captured results that occurred outside of the annual reporting cycle and helped situate the CTA Program in the larger suite of TCS and Government of Canada programs.

Limitations and mitigation measures

| Limitations | Mitigation measures |

|---|---|

Low reach to CTA participants:Due to the high number of surveys CTA participants are expected to participate in following program completion, the evaluation scoped out any extensive contact with participant companies. The evaluation relied on a limited number of case studies to capture participant perspectives and relied on the existing survey data collected by BBA and by the TCS Tools, Analysis and Performance Division (BTB). | The evaluation team reviewed existing surveys to ensure the data needs for the evaluation were covered by existing survey questions. |

Incomplete and inconsistent performance data:Performance data is held in two systems: TRIO (the client relationship management system and key performance indicator [KPI] database) and Strategia, a departmental planning and reporting database. These two databases currently do not communicate with each other directly. TCs enter KPI targets/results into Strategia, and the specific services/interactions/success stories also need to be entered individually into TRIO, which does not always happen. The lack of integration has created data discrepancies and a fragmented account of performance. | The evaluation conducted an extensive review of TRIO data and a meta-analysis of Strategia reports and completed a comparison of data results across indicators. Client survey results were considered to be the most robust and accurate source of performance information and were used in combination with case study results to corroborate findings on effectiveness. |

Challenges in attributing firm successes to CTA Program funding:In the broader context of the Canadian innovation ecosystem, the CTA Program is a relatively small player. Firms that participate in the CTA programs often participate in a number of different Government of Canada trade incentive programs and receive services from other BAIs. Given this context, it is difficult to isolate the impact of the CTA programs from other services that Canadian SMEs received, especially over time. The CTA Program recognizes that its aggregated performance metrics are not always the direct results of CTA funding. | Post-program surveys included questions about whether certain results can be directly attributed to CTA programs. The evaluation assessed CTA Program results by taking into account self-assessment statements by participant companies about whether or not results were directly attributed to the CTA programs. Qualitative statements collected during the case studies support the attribution findings. |

Findings

Responsiveness and relevance

Acknowledging client requirements

Figure 5

Text version

Canadian Technology Accelerators

CTA programs were often repeated to meet demand from multiple cohorts of companies.

CTA programs were generally exceeding targets for services delivered to Canadian companies. Planned strategic meetings targeting local contacts to generate qualified opportunities and recruitment increased in volume and resulted in more insight into the capacity, interests and business needs of clients. The number of initiatives repeated year-over-year increased 200% over the evaluation period, indicating demand has not diminished. Some CTA participants were involved in more than one CTA program, and the majority interacted with more than one mission. Program participant rates remained steady over the evaluation period.

The mixed model of virtual and in-person delivery was beneficial for companies.

The virtual service delivery model offered benefits such as flexibility to meet the needs of companies, balancing requirements for time commitments of busy founders, costly international travel and providing advance knowledge of international markets to lay the groundwork prior to in-person participation. RO respondents suggested that virtual delivery boosted accessibility of programs and contributed to increasing uptake, providing an example of CTA programs in Asia where travel had been a significant barrier. In 2021, CTA coordinators won a departmental Deputy Minister’s Award of Excellence for Innovation for pivoting toward virtual program delivery early and aggressively, by exemplifying effective use of technology and e-collaboration tools and increasing program uptake by 40%. All interview groups noted, however, that on-site activities remained critical to the development of business and business relationships, and could be more productive, stating that being in-market is a big contributor to making meaningful connections.

Companies are looking for a variety of supports, with business to business (B2B), niche markets and international interests increasing in importance.

All key informant interview groups described SMEs as being increasingly interested in obtaining business development support as opposed to learning only about fundraising opportunities and networking. According to RO and BAI interviewees, SMEs demonstrated a stronger interest for international markets and tailored support to facilitate market integration. It is anticipated that there will be more of a shift to niche sectors targeted for export (e.g. agriculture and food technology, mental health, clean technology). With the flexibility and in-depth experience of CTA TCs, the CTA Program is well positioned to respond to future demands.

Meeting needs of Canadian technology SMEs

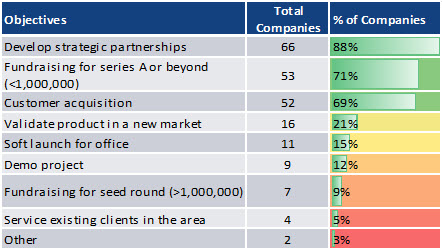

Figure 6: Top objectives in participating in CTA programs

Source: Canadian Technology Accelerator Program Results and Outcomes Report FY 2019-20

Text version

| Objectives | Total Companies | % of Compagnies |

|---|---|---|

| Source: Canadian Technology Accelerator Program Results and Outcomes Report FY 2019-20 | ||

| Develop strategic partnerships | 66 | 88 % |

| Fundraising for series A or beyond (<1,000.000) | 53 | 71 % |

| Customer acquisition | 52 | 69 % |

| Validate product in a new market | 16 | 21 % |

| Soft launch for office | 11 | 15 % |

| Demo project | 9 | 12 % |

| Fundraising for seed round (>1,000,000) | 7 | 9 % |

| Service existing clients in the area | 4 | 5 % |

| Other | 2 | 3 % |

Specialized sector expertise, extensive networks of contacts and hands-on guided service delivered unique value to companies.

CTA clients were more satisfied, and favoured the CTA trade commissioner’s competence and creativity slightly more, than other GAC TC services. All CTA programs were unique to their location and were staffed by sector specialist advisors and corporate partners of CTA missions that were embedded in the sub-sector being targeted. The in-country networking and access to experts, mentors, advisers and key market contacts, along with high-touch, hands-on, guided service related to in-country markets, were beyond what was available in other GAC programs. The Program’s status as a government-run opportunity was noted by mission and case study interviewees as a factor that added credibility to the Program, and allowed for additional opportunities (e.g. links to bigger players and potential investors, access to key events, access to government agencies).

The CTA Program was adaptable and flexible, which increased its capacity to be responsive.

The Program’s design allowed for delivery in many different markets, covering different sectors and sub-sectors, with the ability to pivot and expand into new and emerging sectors (including specializing to specific fields) as needed in order for participants to meet their business objectives.

The CTA Program was able to be responsive to changes in a given sector (regionally and geographically) and also to the changing needs of individual SMEs. Key informant interviewees stated that the Program allowed missions to deliver programming that was innovative, customizable and tailored to the needs of clients.

According to the BBA Canadian Technology Accelerator Program Results and Outcomes Report FY 2019-20, orientation, networking and mentorship services were considered highly beneficial to participating companies and contributed to the most important objective reported by participants: that of developing strategic partnerships (88%).

Niche and distinctiveness in the international business development ecosystem

The CTA Program was complementary to other TC services and different from other Government of Canada and BAI program offerings.

All interviewee groups considered the CTA programs to be unique among other trade promotion and incentive programs. Potential participants in CTA were most often referred to the program through other Trade Commissioners, both in Canada and from abroad, as it was more sector specific.

The evaluation found that the CanExport SMEs programFootnote 3 could be complementary to the CTA. This program provides access to up to $50K in funding to support small- and medium-sized companies with international market development activities. These funds could be used to cover travel to attend a CTA program or to support initiatives that firms may undertake post-CTA program participation. CanExport representatives have been invited to present to CTA program cohorts about this funding program. However, mission interviewees explained that the timing of CanExport applications did not always align well with the timing of CTA program participant selections (meaning that not all CTA participants could leverage CanExport to fund their participation) or with the end of CTA programs (meaning that participants could be introduced to CanExport while the program was already closed for the year).

Compared to other BAI services and some government crown corporation programs, the non-requirement for an equity position and the free nature of the service were highlighted as key differentiators, along with the extensive built-up expertise, international in-market sector knowledge and networks; and tailored, high-touch, client-centric focus.

Equity, diversity and inclusion

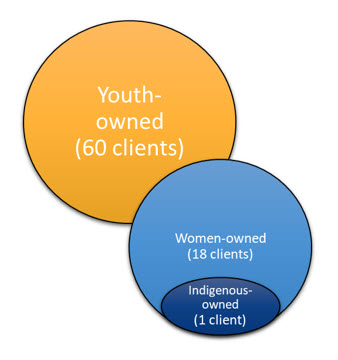

Figure 7: CTA participants by underrepresented group

Source: CTA database - EDI data for CTA firms (FY 2018-21)

“Youth” is defined as a person aged between 18 and 39, as documented by Diversity, FTA Promotion, Trade Missions and Outreach (BPE).

Text version

- Youth Owned (60 clients)

- Women Owned (18 clients)

- Indigenous Owned (1 clients)

- Women Owned (18 clients)

Source: CTA database - EDI data for CTA firms (FY 2018-21)

“Youth” is defined as a person aged between 18 and 39, as documented by Diversity, FTA Promotion, Trade Missions and Outreach (BPE).

The Program encouraged equity, diversity and inclusion (EDI) considerations. However, there was no formal GBA Plus strategy or analytical approach in place.

There was no specific GBA Plus strategy in place for the CTA Program. However, some GBA Plus considerations were built into program delivery, and the Program implemented some EDI-related initiatives during the evaluation period.

The Program website encouraged participation from companies led by members of underrepresented groups. The CTA Program SOP also included a commitment to supporting high-potential Canadian companies that were women-led or women-owned, or led by Black, Indigenous, People of Colour (BIPOC), youth and/or 2SLGBTQI+ entrepreneurs. TCs involved in CTA program delivery were encouraged to engage companies led by Canadians of all backgrounds and orientations to apply for a CTA program.

The SOP also encouraged CTA staff to consider creating programs exclusively for high-potential companies with leaders from a specific underrepresented group in a sub-sector. There have been seven CTA programs dedicated to women-owned firms between FY 2018-19 and 2021-22. However, interviewees from regional offices, missions and HQ indicated that, as CTA programs already aimed to recruit very specific clientele, narrowing the focus to a subset of potential participants based on GBA Plus considerations could have made recruitment more difficult as there would not have been a large enough pool of potential participants to draw from. Also, running such specific programs could have been difficult in some global locations where cultural differences added challenges.

Staff were also encouraged to develop programming adapted to participants and to ensure diversity, equity and inclusion in the selection process. However, there was no standardized approach and no guidelines as to how to evaluate applications with an EDI lens. The evaluation found that EDI and GBA Plus were approached differently across missions.

Since 2018, the Program has allowed participant companies to self-identify as either women-owned, youth-owned (18 to 39 years old) or Indigenous-owned. This data was available for 70 CTA firms in TRIO, representing approximately 10% of all program participants during the evaluation period. The available data showed the number of firms from underrepresented groups increasing over the last three years. However, it is unclear whether this was because more clients from underrepresented groups were participating in CTA programs or because more clients were choosing to self-identify. Some Strategia reports also indicated participation of underrepresented groups; for example, companies with women in leadership positions and BIPOC-led firms.

Efficiency

Internal governance and coordination

Figure 8

Text version

- Performance

- Vision

- Leadership

- Team

- Policies

- Integrity

- Knowledge

- Role

- Governance

- Strength

- Support

- Responsibilities

- Outcomes

- Development

- Partnership

- Governance

- Training

- Effective

- Team

- Duties

Governance was appropriate and roles and responsibilities were clarified, but more insight to capacity challenges was needed.

All GAC interviewees considered the CTA Program’s decision-making structure to be effective. Missions had the flexibility to decide and propose CTA programs appropriate to their context, while BBA made funding decisions and ensured basic consistency among CTA offerings. In addition, the new CTA standard operating procedures from FY 2020-21 had clarified roles and responsibilities across program delivery for HQ, regional offices and missions and at all stages of delivery. Although roles and responsibilities were clear to internal stakeholders, the majority of companies interviewed through case studies did not have a clear understanding of the distinctive roles of HQ, ROs and missions. However, this did not negatively impact their experience.

Trade commissioners’ roles were found through the case studies to be clear and meeting companies’ expectations. For instance, companies were satisfied with the tailored in-person support offered, the continued engagement post-CTA program, and TCs’ ability to identify opportunities and make connections.

Some areas for improvement remained. HQ interviewees noted that centralized governance at HQ tended to be slow, which could be an issue given the fast pace of business at missions and for SMEs. Some interviewees considered that insights from ROs could be better considered when designing CTA programs to ensure they are coherent with Canadian demand and interests. Some interviewees also pointed out that some TCs in missions and in ROs cumulated several responsibilities (for other programs or for a sector, for example) in addition to the CTA Program, which caused capacity challenges.

Coordination greatly improved. However, opportunities for increased cohesion remained.

Through the introduction of the SOP in FY 2020-21 and annual work planning meetings, coordination and communications improved significantly between missions, ROs and HQ. Staff had forums to brainstorm, share lessons learned and best practices, and discuss collaboration opportunities. Interviewees valued this joint planning process.

There was evidence that indicated activities could be further synchronized across missions, HQ and ROs—who worked, respectively, by cohorts, fiscal year or continuously—to build a cohesive calendar. Moreover, information sharing between missions and ROs could have used strengthening (e.g. company applications, successes and feedback to inform programming) as well as improvements to the “handover” of participants back to ROs after the CTA programs, i.e. to ensure follow-ups were done and the relationship was maintained between the Canadian regional TC and participating firms.

Recruitment was sound but presented challenges for some missions abroad.

All program stakeholders considered the recruitment of participants to be fair. At some missions, external stakeholders (mentors, partners and investors) were involved in selection, which added market validation and credibility to the process. Case study respondents appreciated the opportunity to demonstrate their readiness and interest through application interviews—i.e. to “earn their spot.”

However, a few GAC interviewees noted that high-performing companies in different regions could be of different sizes, and that some firms which generated lower revenues may not have had (or perceived that they did not have) high chances of being selected for CTA programs (e.g. a high-performing firm from the Maritimes may have had much lower revenues than a Toronto-based company in the same sector). Regarding transparency, CTA missions did not all provide the same level of information as to why some firms were not selected. This lack of feedback could become an issue for ROs managing the client relationship. Interviews and documentation also indicated that there could be inconsistency in how criteria (e.g. “potential to scale” or “coachability”) were understood or applied across missions and sectors.

According to interviews and documents, factors that supported recruitment included:

- the networks maintained by trade commissioners and regional offices, and the regional office–client relationships

- some existing relationships within TCS and with some OGDs and BAIs

- the positive testimonies of CTA program alumni

- a balanced use of virtual and in-person program activities

Also, coordinating CTA program delivery and recruitment between missions and with ROs remained paramount because of the potential overlap in outreach to the same pool of companies.

Some factors made recruitment more challenging, including that Canadian companies were known to have less interest in considering, or limited resources to consider, certain international markets (due to travel costs, different language, significant cultural differences, etc.).

Internal capacity challenges at ROs and missions, along with rushed timeframes and competition between accelerator programs writ large, may also have complicated recruitment. Identifying or attracting participants for a CTA program with very narrow criteria might also have proven to be challenging (e.g. specific sub-sectors, or firms owned by underrepresented groups in a given sector). Some interviewees argued that better communication around what the CTA Program is and what its value is could have improved recruitment, along with stronger connectivity with the SME accelerator and incubator ecosystem in Canada.

Performance measurement

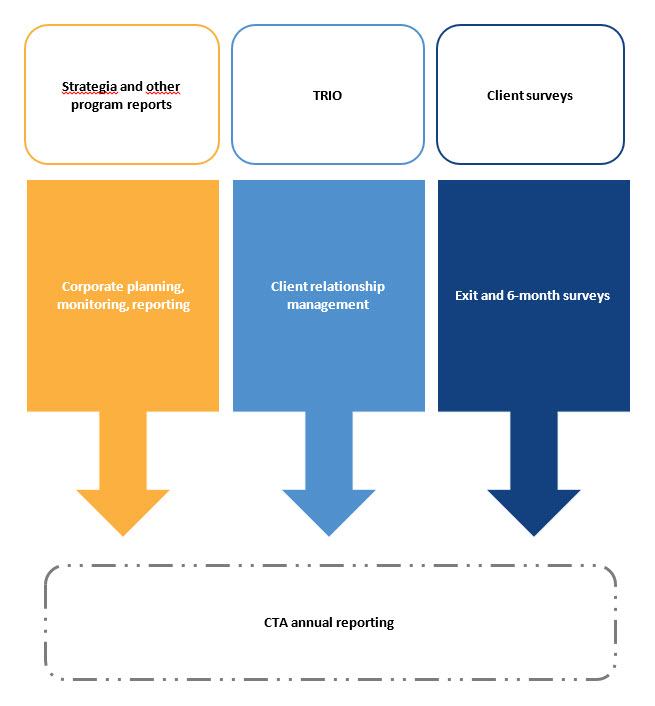

Figure 9

Text version

Organigramme outlining the different means of monitoring CTA program result for the annual reporting.

Performance monitoring was cumbersome and did not generate consistent, useful information.

CTA program results were captured in Strategia reports, end-of-program reports and in the TRIO database, along with responses to a 6-month post-CTA program survey administered to participants. KPIs tracked in TRIO included interactions, services delivered, and outcomes, based on guidelines and definitions available in program documentation. HQ synthesized and analyzed CTA programs’ data to produce an annual internal results and outcomes report.

Manual data entry and varying interpretations of definitions made it challenging to gather consistent information. Response rates to surveys were low—the average exit survey response rate for FY 2019-20 CTA programs was only 19%, with most programs seeing zero responses—and there was varying success with qualitative follow-ups. In addition, some outcomes took longer than six months to materialize, and certain important but more “intangible” benefits of CTA programs were not captured in KPIs (e.g. collaboration between firms or the impact of a firm avoiding ill-advised investments), indicating the Program’s theory of change may not have been accurate and complete. Successes were noted to also potentially vary by mission, market and company stage of development, and to be conceived differently by HQ, missions and participants (e.g. getting a company interested in a market could be seen as a success in itself for some missions).

“Economic outcome facilitated” (EOF) was another KPI used to capture CTA Program-related impacts. An EOF corresponded to “a measurable result achieved by a TCS client with a local business, such as a new commercial transaction or a significant commercial development, which directly contributes to Canadian economic prosperity” (TCS definition). This is an example of an area where the data did not offer a clear quantitative picture. No EOF was captured in TRIO data in FY 2016-17 or 2017-18, and eight EOFs were reported from FY 2018-19 through 2020-21, for all CTA programsFootnote 4 Comparatively, the review of a sample of Strategia reports indicated that there were EOFs beginning in FY 2016- 17, and 60 in total over the 5 years up to FY 2020-21.

The extent to which CTA programs have facilitated other economic outcomes was unclear.

Effectiveness

Achievement of short-term outcomes

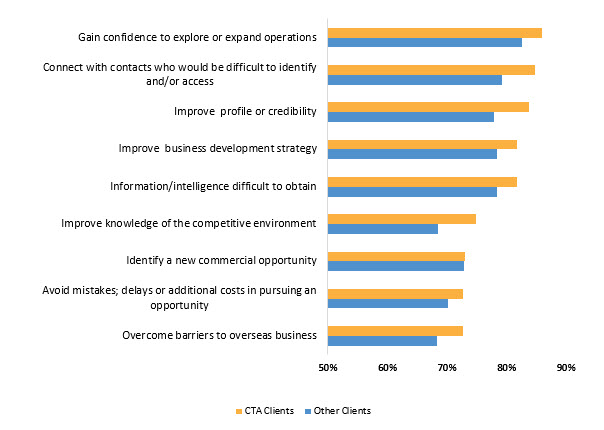

Figure 10

Text version

| Outcomes | CTA clients | Other clients |

|---|---|---|

| Gain confidence to explore or expand operations | 86 % | 82.6 % |

| Connect with contacts who would be difficult to identify and or access | 84.7 % | 79.3 % |

| Improve profile or credibility | 83.8 % | 77.9 % |

| Improve business development strategy | 81.8 % | 78.4 % |

| Information/intelligence difficult to obtain | 81.7 % | 78.4 % |

| Improve knowledge of competitive environment | 74.9 % | 68.5 % |

| Identify a new commercial opportunity | 73 % | 72.8 % |

| Avoid mistakes; delays or additional coasts in pursuing an opportunity | 72.7 % | 70.1 % |

| Overcome barriers to overseas business | 72.7 % | 68.4 % |

“[It was] a huge piece of learning for us in the different regions we were looking at. We were completely off the mark in how we were initially going to approach [that new market]. Now we are targeting things in a different way.”

- Case study respondent

The CTA programs were effective at increasing the client base of program participants.

The evaluation gathered evidence that the CTA programs contributed to increasing the client base of program participants. Among CTA program participants surveyed between FY 2017-18 and 2020-21, over 80% reported that the TCS helped them gain confidence to expand operations in a foreign market and connect with customers, partners or other contacts who would have been difficult to identify and/or access without TCS. This result was greater than the impact noted by other TCS clients. The case studies also illustrated this impact, which varied in scale depending on the firm. Case study companies reported, for example:

- a major increase in client base since participation in the CTA Program

- a gain of 10 to 15 new customers from participating in a Munich CTA program and 3 to 5 new clients identified through a California CTA program

- three new clients identified immediately following CTA program participation, which “wouldn’t have happened” without the program

The CTA programs had a positive impact on program participants’ business strategies and often prompted strategy pivots.

There was also credible evidence that CTA programs had a positive short-term impact on the business strategy of participants. Survey results indicated that the CTA programs helped participating firms:

- access information or intelligence that would be difficult to obtain without TCS assistance

- improve or pivot their business development strategy in foreign markets

- strengthen their fundraising strategy

- reduce risks and uncertainties in the new market

All case study firms reported a positive impact on their business strategy from a CTA program. For instance, the program allowed participants to re-evaluate the relevance of certain opportunities, learn of linkages to other industries, and prioritize certain markets over others.

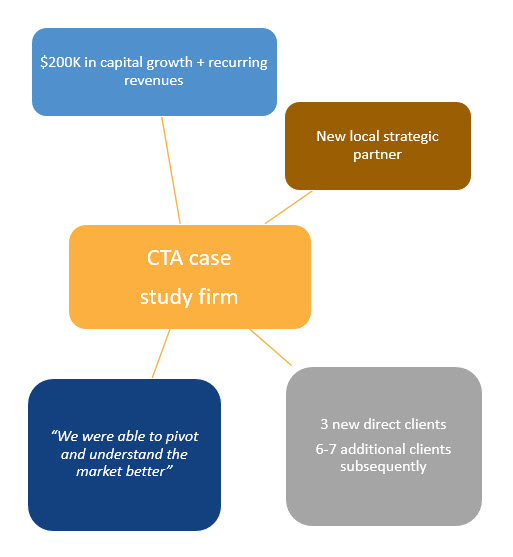

Figure 11

Text version

CTA case study firm:

- $200K in capital growth + recurring revenues

- New local strategic partner

- “We were able to pivot and understand the market better”

- 3 new direct clients 6-7 additional clients subsequently

The CTA programs can contribute to an increase in revenue for participating firms.

The evaluation found that CTA programs can contribute to revenue growth when participating firms gain direct access to new clients, improved their connections in the market and refined their business strategies.

From FY 2016-17 to 2019-20, about half of CTA companies that participated in follow-up surveys (N=148) reported growth in revenues following participation. The amount of increased revenue varied by year and declined overall since FY 2016-17 (but the response rate for the surveys had also declined).

Case studies showed that impact on revenue also varied on a case-by-case basis but could be significant. For instance, one company described a 300% growth in revenue post-CTA program participation and confirmed that the program had contributed to this growth. Another attributed $200,000 in capital raised and $50,000-$60,000 in licence-fee growth to CTA program-facilitated developments. In contrast, another case study interviewee noted a small impact on revenue growth, through gaining one international client.

The Program can have positive impacts on job growth for participating firms, but this was not a priority objective.

Based on qualitative evidence, the CTA programs can contribute to job growth where participating companies identify growth opportunities abroad and need to expand their capacity in Canada or abroad as a result. For instance, some CTA survey participants described a need to hire additional staff in a foreign market to help manage new partnerships or expand sales. The case studies also supported this: two companies reported job growth (new hires in R&D or administration, for instance) to respond to increased demand to which the CTA Program had contributed. However, the other case study companies did not see a link between job growth and their participation in the program. On the whole, CTA program participation may have indirectly contributed to job growth, but this was not a priority for participating firms, nor a central objective of the Program.

The Program can contribute to an increase in capital.

About 40% of CTA participant firms surveyed from FY 2016-17 to 2019-20 reported an increase in capital after taking part in a CTA program. CTA program mentorship helped some firms refine their pitch, build a better plan or get validation from key opinion leaders. Two case study respondents indicated the CTA program contributed to their firms raising capital: one raised $6M through an investment group, another indicated that the program’s impact on their fundraising activities allowed them to secure venture-backed capital. However, two others either already had capital prior to participating in the CTA program or raised capital after their participation but not as a result of the program. This illustrates that firms participated in CTA programs for different objectives; while some had interest in fundraising, business development was more important to others.

Figure 12

Text version

Bubble with the quote:

“[The CTA Program] has definitely increased our client base. We’re an early-stage commercial company, and we’re seeing phenomenal growth. Hundreds of percent increase. It helped open the market and make introductions to partners who have helped us increase our business.”

- Case study respondent

Matchmaking and connectivity were among the most valued aspects of the Program.

The ability of the TCs to introduced CTA program participants to potential clients and partners was perhaps the most important benefit of this Program. Connections made in the context of the CTA programs were the main vector of impact, leading to firms learning, improving their approach and achieving positive economic outcomes.

On average, two-thirds of annual survey respondents from FY 2016-17 to 2019-20 (N=148) reported a growth in strategic partnerships after their CTA program participation. Being in-market and engaging as part of a credible government-run program helped participants make meaningful connections. Firms also benefited from peer-to-peer learning to navigate relationships in the foreign market.

All internal interviewee groups engaged for the evaluation cited examples of success stories related to partnerships (e.g. partnerships with clients; meeting local partners for trials, pilots and demonstrations; identifying new providers; deals with distributors, etc.). Three case study respondents explicitly stated that the matchmaking component of the CTA Program had generated the most important long-term benefits for their companies (leading to more exposure, revenue growth and new clients) and the other two saw significant impact as well (recognition and connections).

However, it was difficult to report on this quantitatively because of data inconsistencies. TRIO data indicated that 18 strategic partnerships linked to CTA Program participation occurred from FY 2018-19 to 2019-20, but the BBA Results and Outcomes Report from FY 2019-20 showed a much larger number of 109 strategic partners identified during the period. The BBA report draws data from multiple sources.

The evaluation revealed no major unintended outcomes of the Program, whether positive or negative.

A few respondents mentioned that connections between participating firms within a CTA program cohort could lead to unexpected positive outcomes through collaborations (e.g. mergers). Less positively, a few HQ interviewees noted that, on occasion, CTA companies would be bought out by international interests once introduced to international markets, but this was not identified as a trend. Finally, the CTA program's move to virtual delivery in response to COVID-19 restrictions, while not an original program design element, led to unintended positive outcomes and a number of benefits for CTA program participants.

Lessons learned

| Design | Delivery | Process |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Conclusions

Responsiveness and Relevance

The CTA programs met the needs of Canadian SMEs.

The free, tailored, intensive support and valuable connections offered by the CTA programs uniquely responded to the interests and needs of SMEs. Program participant rates remained steady, with some firms participating in multiple programs and most firms interacting with multiple missions. CTA programs were often repeated to meet sustained demand and virtual delivery contributed to increased uptake. All of this indicates that the Program remained relevant and of value for firms.

Support for underrepresented groups was evident, but more development is needed.

The Program encouraged participation from companies led by members of historically underrepresented groups, and CTA staff at missions were encouraged to develop programs for specific clienteles. However, there was no formal GBA Plus strategy or analytical approach. While evidence confirmed participation of entrepreneurs from underrepresented groups, it cannot establish whether that participation increased or was appropriate (i.e. what good representation would look like) over the evaluation period and GBA Plus was not evenly considered across missions.

Efficiency

Management and administration became more efficient, with opportunities for ongoing continuous improvement.

Governance was appropriate and roles and responsibilities were clarified, but there was a need for more insight to capacity challenges at missions and ROs. Coordination has greatly improved over recent years, but more strengthening could be done – namely, to create a cohesive program calendar across posts and further leverage regional office expertise in the design of CTA programs.

Performance measurement is a burdensome process for clients and staff, and is not enabling efficient or effective reporting.

There are multiple platforms containing performance data that cannot be reconciled, multiple instruments used to collect and extract performance information, and inconsistent and/or non-use of the tools available to TCs and clients. It is not possible for the Program to provide reliable insight to outcomes achieved without the ability to have structured, consistent data. Additionally, performance indicators being used do not capture the right measures at the right times in a client journey. There are immediate outcomes being missed and data for longer-term outcomes is collected too early.

Achievement of Outcomes

Short-, medium- and long-term outcomes were being achieved.

The CTA programs enabled participating firms to find new clients, update their strategies, increase their revenue and raise capital. The ability of the TCs to introduce CTA participants to potential clients and partners was perhaps the most important benefit of this program. Connections made in the context of the CTA were the main vector of impact, leading to firms learning, improving their approach and achieving positive economic outcomes. However, performance monitoring was cumbersome and was not geared to generating clear evidence and congruent data.

Lessons learned were beneficial and can lead to sustained efficiencies.

The CTA programs demonstrated the effectiveness of a hybrid delivery model and the benefits of coordination and multi-mission programming. Stakeholders highlighted the importance of identifying well-prepared companies and collaborating for recruitment, while using the Program’s flexibility to address a growing interest in international business development. The program has also seen the benefits of CTA alumni engagement and of encouraging engagement between participants within cohorts.

Recommendations

- Management of the International Business Development, Investment and Innovation Branch (BFM) should improve its capacity to measure impact and collect evidence to assess and demonstrate how it fulfills market demands. This includes:

- a revisit of the Program’s theory of change in order to better recognize the diversity of intended outcomes for participating companies and identify those for which performance is not currently reported

- a review and redefinition as required of performance indicators for meaningful and feasible data collection by the Program, ensuring one data platform contains all reliable information

- identifying alternative means and sources to gather information on difficult to capture outcomes that would inform on the impact of the CTA Program

- addressing challenges of current reporting methods for CTA participants and staff to ease reporting processes

- Management of BFM Branch should fine-tune its outreach approach and assess its results in participant reach. This means:

- in view of increasing equity, diversity and inclusion, put in place proactive measures, according to distinct CTA program contexts, to increase outreach to diverse populations as potential participants (e.g., SMEs led or owned by underrepresented groups; SMEs in less populated areas; etc.)

- increase capacity of missions to use a GBA Plus lens in selection process and ensure consistency in the collection of EDI data and GBA Plus analysis

- gather consistent information on applicant firms and application evaluation results to enable meta-analysis of the client population

- develop a consistent approach to providing feedback to unsuccessful firms

- Management of BFM Branch should enhance program coherence by establishing a cohesive program calendar (including coordination of recruitment) and more even level of involvement of all regional offices (ROs).

Considerations

Continuous learning and improvement

GAC should look at how to better align its programs and horizontal connections among programs that can enhance or leverage advantages of trade enhancement opportunities for companies. It could also look at how to promote an increased focus on collaboration and the identification of synergies with other international business accelerators and incubators in the ecosystem (including other government programs) as a pipeline, or potential next step, for future trade accelerator program participants.

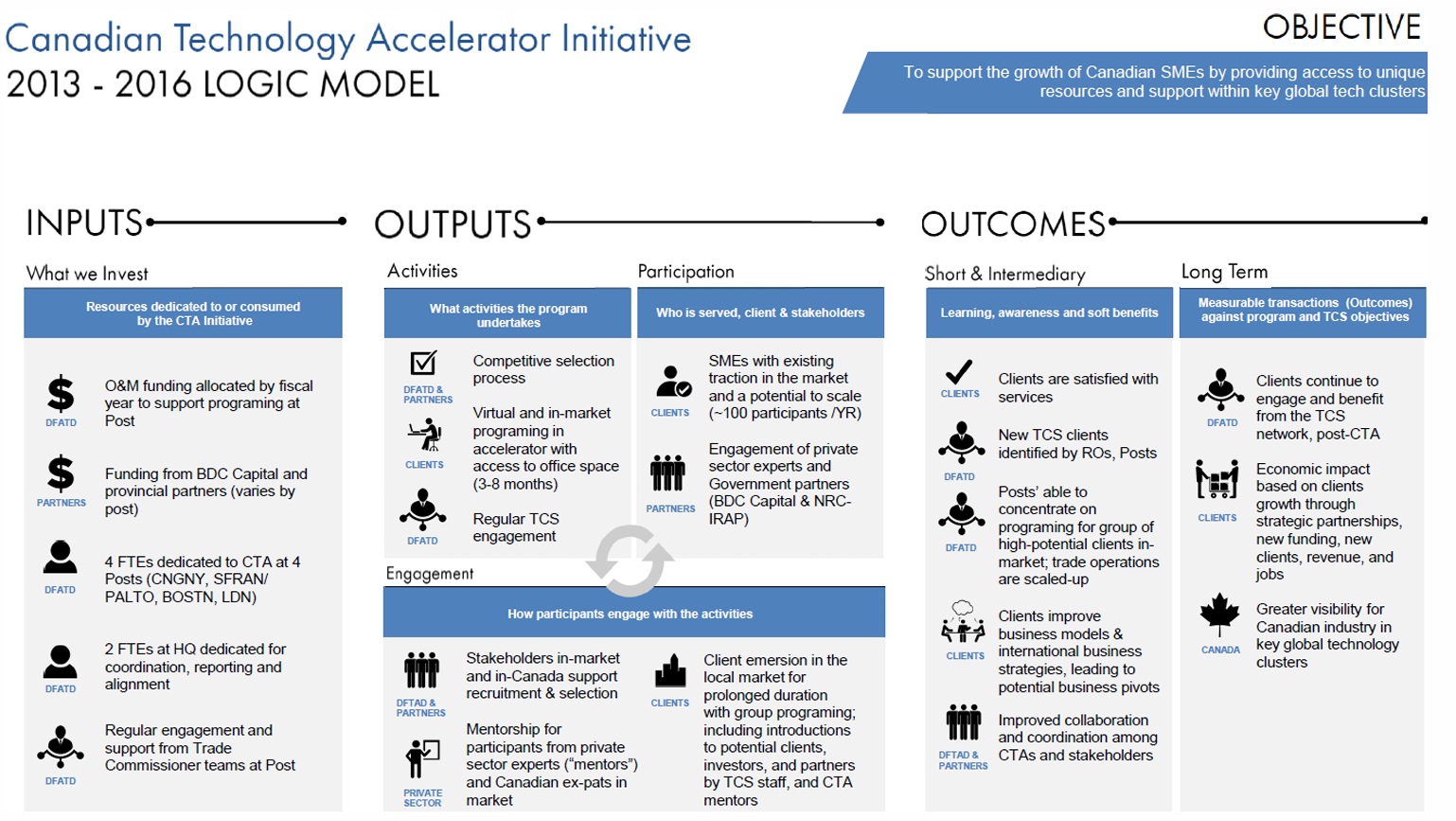

Annex: Logic model

While the CTA Program does not currently use this logic model, it is useful to help understand the intervention.

Figure 13

Text version

Canadian Technology Accelerator Initiative - 2013-2016 Logic model

Objective: To support the growth of Canadian SMEs by providing access to unique resources and support within key global tech clusters.

Inputs

What we Invest

Resources dedicated to or consumed by the CTA Initiative:

- DFATD: O&M funding allocated by fiscal year to support programing at Post

- PARTNERS: Funding from BDC Capital and provincial partners (varies by post)

- DTATD: 4 FTEs dedicated to CTA at 4 Posts (CNGNY, SFRAN/PALTO, BOSTIN, LDN)

- DTATD: 2 FTEs at HQ dedicated for coordination, reporting and alignment

- DTATD: Regular engagement and support Trade Commissioner teams at Post

Outputs

Activities

What activities the program undertakes:

- DFATD & PARTNERS: Competitive selection process

- CLIENTS: Virtual and in-market programing in accelerator with access to office space (3-8 months)

- DFATD: Regular TCS engagement

Participation

Who is served, client & stakeholders:

- CLIENTS: SMEs with existing traction in the market and a potential to scale (∿ 100 participants/YR)

- PARTNERS: Engagement of private sector experts and Government partners (BDC Capital & NRC-IRAP)

[ROTATING ARROWS]

Engagement

How participants engage with the activities:

- DFATD & PARTNERS: Stakeholders in-market and in-Canada support recruitment & selection

- PRIVATE SECTOR: Mentorship for participants from private sector experts (“mentors”) and Canadian ex-pats in market

- CLIENTS: Client emersion in the local market for prolonged duration with group programing; including introductions to potentials clients, investors, and partners by TCS staff, and CTA mentors

Outcomes

Shorts & Intermediary

Learning, awareness and soft benefits:

- CLIENTS: Clients are satisfied with services

- DFATD: New TCS clients identified by Ros, Posts

- DFATD: Posts’ able to concentrate on programing for group of high-potential clients in-market; trade operations are scaled-up

- CLIENTS: Clients improve business models & international business strategies, leading to potential business pivots

- DFTAD & PARTNERS: Improved collaboration and coordination among CTAs and stakeholders

Long Term

Measurable transactions (Outcomes) against program and TCS objectives:

- DFATD: Clients continue to engage and benefit from TCS network, post-CTA

- CLIENTS: Economic impact based on clients growth through strategic partnerships new funding, new clients, revenue, and jobs

- CANADA: Greater visibility for Canadian industry in key global technology clusters

- Date modified: