Evaluation of International Assistance Programming in Haiti

2016-17 to 2020-21

Evaluation Report

Prepared by the Evaluation Division (PRA)

Global Affairs Canada

June 2023

Acronyms and Abbreviations

- BINUH

- United Nations Integrated Office in Haiti

- CARICOM

- Caribbean Community and Common Market

- CDB

- Caribbean Development Bank

- CERF

- Central Emergency Response Fund

- CIDA

- Canadian International Development Agency

- CSO

- Civil society organization

- DAC

- Development Assistance Committee (OECD)

- DPI

- International Assistance Programming Process and Coordination Division

- ECOSOC-AHAG

- Ad Hoc Advisory Group on Haiti

- FIAP

- Canada’s Feminist International Assistance Policy

- FIPCA-PNH

- Initial Training and Professional Development for the Haitian National Police's Managerial Staff

- GAC

- Global Affairs Canada

- GBA Plus

- Gender-based Analysis Plus

- GE

- Gender equality

- IBRD

- International Bank for Reconstruction and Development

- IDB

- Inter-American Development Bank

- IFM

- International Security and Political Affairs Branch

- IOM

- International Organisation for Migration

- IMF

- International Monetary Fund

- KFM

- Partnerships for Development Innovation Branch

- MCFDF

- Ministry on the Status and Rights of Women in Haiti

- MENFP

- Ministry of National Education and Vocational Training

- MFM

- Global Issues and Development Branch

- MHD

- International Humanitarian Assistance

- MINUJUSTH

- United Nations Mission for Justice Support in Haiti

- MINUSTAH

- United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti

- MNCH

- Maternal, Newborn and Child Health

- NDH

- Haiti Division

- NAPWPS

- Canada's National Action Plan on Women, Peace and Security

- NGM

- Americas Branch

- NGO

- Non-governmental organization

- NPA

- National Police Academy

- NPO

- Non- profit organization

- OAS

- Organization of American States

- ODA

- Official development assistance

- OECD

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development

- OCHA

- United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs

- OIF

- International Organisation of La Francophonie

- PAHO

- Pan American Health Organization

- PAMREF

- Revenue Generation Support Project in Haiti

- PARGEP

- Public Sector Management Support Project

- PATH

- Field Support Services in Haiti Project

- PIRFH

- Computerization of the Land Registry in Haiti

- PNH

- Haitian National Police

- PRA

- Evaluation Division

- PRISMA II

- Integrated Management of Maternal and Child Health in Artibonite

- PSAT

- Field Support Services’ Project

- PSDH

- Haiti's Strategic Development Plan

- PSOP

- Peace and Stabilization Operations Program

- SGF

- Financial Management Grants and Contributions

- RBM

- Results-based management

- SYFAAH

- Agriculture Finance and Insurance System in Haiti Project

- UN

- United Nations

- UNDP

- United Nations Development Programme

- UNFPA

- United Nations Population Fund

- UNICEF

- United Nations Children's Fund

- USAID

- United States Agency for International Development

- WFP

- World Food Programme

- WHO

- World Health Organization

Executive Summary

Global Affairs Canada's Evaluation Division (PRA) conducted an evaluation of Canada's international assistance program in Haiti from 2016-17 to 2020-21 to assess the extent to which international assistance has been aligned with priorities and optimized for development objectives in a context of persistent fragility. The evaluation serves to support decision-making on the future direction for program improvement. Questions focused on relevance to country needs and to the FIAP priorities, efficiency in delivery, coherence across international assistance channels and among donors, and achievement of results.

The profile of Canadian international assistance showed a de facto alignment with the social and institutional priorities of Haiti’s Development Plan (Vision 2030), notably through significant funding to multilateral partners, in line with national priorities. However, challenged by the deteriorating political and security situation, the program was mostly reactive to Canadian departmental priorities and only developed a strategic plan at the end of the period. There was no comprehensive analysis to anchor cross-sectoral collaboration and systematically address multiple vulnerabilities, risks of conflict and disaster, and conditions that weaken governance structures. A strategic analysis of environmental issues in Canada’s development effort, given the country’s vulnerabilities, lacked as a framework for projects, and some important projects gave little consideration to these issues despite valuable initiatives that included elements of risk mitigation and prevention. The modalities for advancing gender equality (GE) could have considered better the links of humanitarian, security and development sectors in a cross-cutting manner (the triple nexus perspective). The program and project-based management approach, supporting relevant but short-lived initiatives, resulted in a uniform weakness in achieving or demonstrating results beyond outputs.

Since 2017, the program has invested heavily in advancing GE across all streams, in alignment with the FIAP. GAC has exercised significant leadership on the GE agenda in overall programming, including at sectoral tables and in multi-donor collaborations. This has amplified GAC's impact beyond Canadian projects but still had a moderate influence on GE agendas and modalities in multilateral partnerships. Results on GE are mixed, difficult to measure, and more practical (service provision, training, etc.) than transformative from a feminist perspective. However, GE is now a top priority on the global development agenda in Haiti and included in Haitian government policies in part because of these efforts.

Using a triple nexus approach in a country such as Haiti could maximize the coherence and impact of international assistance. Yet the various sectors had few incentives and mechanisms to work collaboratively and generally operated in silos, with no interlinked objectives. Tangible progress made through governance, sustainable agriculture, and health initiatives was tempered by short duration of projects (4,3 years on average) and lack end-of-project plans to consolidate gains in the context of growing instability and insecurity. The often ambitious objectives faced operational hurdles and monitoring deficiencies that have limited the achievement of results and cast doubt on sustainability. However, Canada’s program in the highly challenging context succeeded in attaining positive short-term results and outputs that could be leveraged through sustained support and a more focused, longer-term vision, including more systematic engagement with selected Haitian partners, as the situation permits.

Summary of recommendations

- NDH should focus the program in Haiti, targeting a limited number of intervention pillars and a longer-term programmatic approach that can maximize the impact of Canadian international assistance on structural strengthening, stability and governance, and sustainability.

- NDH should ensure continued and strengthened collaboration with Haitian stakeholders (credible and legitimate actors from the Haitian state, Haitian civil society, and local communities) in international assistance planning to foster project ownership, the use of endogenous solutions, and the sustainability of results from a localization of aid perspective.

- NDH should mobilize branches active in Haiti (IFM, KFM, MFM) to develop a collective analysis of the context of fragility and vulnerability to improve linkages between program streams in a triple nexus approach and programming effectiveness.

- NGM should develop a human resources strategy to equip HQ and mission with the required capacity and skills, for example, by identifying surge capacity to meet increased workloads and prioritizing the recruitment of staff with experience in managing development programs related to the triple nexus.

Program Background

Haiti Country Context

Figure 1:

Text version

Figure 1: Map of Haiti and its 10 departments.

Administrative Divisions in Haiti

Haiti is divided into 10 departments, each of which is subdivided into three levels: arrondissements (42), communes (145) and communal sections (571).

The communal section is the smallest administrative territorial entity. Each communal section is administered by an executive body, the Communal Section Administration Council (CASEC), and a deliberative body, the Communal Section Assembly (ASEC).

A country with limited economic resources, plagued by frequent natural disasters

Haiti, the poorest country in the Americas and one of the poorest in the world, has seen its fragile economy deteriorate in recent years, with a declining gross domestic product (GDP) since 2019 and a severely devalued currency (the Haitian gourde). Gross national income in 2021 was US$1,420 compared to a regional average of US$15,092. In 2021, an estimated 87% of the population was living in poverty. Remittances from the Haitian diaspora and the remuneration of international workers in Haiti represented 23.8% of GDP in 2020, illustrating the difficulty of generating resources through domestic economic activity.

Haiti is the 3rd country in the world most affected by extreme weather events between 2000 and 2019. Between 2016 and 2021, the country experienced 22 natural disasters or climatic events, the deadliest being Hurricane Matthew in October 2016 and the earthquake of August 14, 2021. Over 96% of the population is extremely vulnerable. The difficult economic situation coupled with these disasters have contributed to the steady decline since 2017 in the Human Development Index (HDI), where Haiti ranks 163rd out of 191 countries.

A deteriorating political and security situation

Politically, the last decade has seen postponements and cancellations of elections (postponement of senatorial elections from 2012 to 2014, cancellation of the 2015 elections, postponement of the 2019 general elections). The presidency of Jovenel Moïse, inaugurated in February 2017, was marked by the PetroCaribe scandal of misappropriation of oil revenues, subsequent protests paralyzing the country (Peyilock), the rise of control by armed gangs and the increase in criminal and political violence (La Saline massacre in 2018, 71 dead). Since the assassination of President Moïse on July 7, 2021, the multidimensional political, economic, humanitarian, and security crisis has continued to worsen: unlikely return to constitutional order, lack of elected governance at all levels of the state, deterioration of people’s security and living conditions, mass exodus abroad, resurgence of food insecurity and cholera, and growing control of strategic areas by criminal gangs.

A society disrupted by economic and gender inequality

A wealthy and highly influential urban Haitian elite represents 20% of the country's population but controlled over 64% of the total wealth in 2014. Haiti is the country with the highest gender inequalities in the Americas.Footnote 1 Although the principles of equality between men and women are enshrined in a policy and in the State's strategic plan, women are victims of exclusion from production and governance systems, suffer from violations of their rights and live in conditions of physical and economic vulnerability that permanently affect their lives. Maternal mortality rates increased from 2000 to 2017, and it is estimated that 26% of Haitian women experience domestic violence in their lifetimeFootnote 2. Women are more likely than men to be in insecure employment (81.3% vs. 65.6%) even though the gender gap in employment rates has narrowed over the past 20 years. While 35% of the Haitian population had internet access in 2020, only 7% of women and girls did, limiting their access to information and resources.Footnote 3

Context

Key Events and Milestones in Haiti

| Years | Key events | Milestones |

|---|---|---|

2016 | Hurricane Matthew |

|

2017 | Jovenel Moïse election |

|

UN deployments | ||

2018 | PetroCaribe scandal |

|

2019 | Peyilock |

|

End MINUJUSTH | ||

2020 | COVID-19 pandemic |

|

2021 | Jovenel Moïse assassination |

|

Earthquake |

Donor Relations

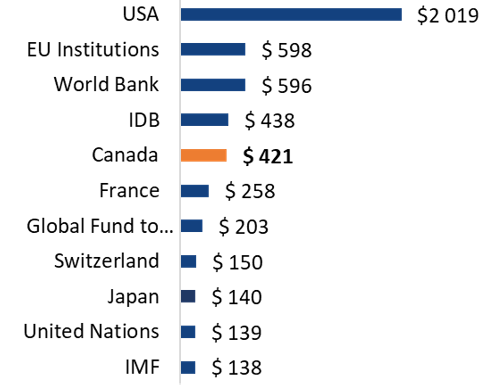

Canada was the 2nd largest bilateral donor after the United States, and the 5th largest donor in overall official development assistance (ODA) disbursed to Haiti from 2016 to 2021.

Net ODA received in Haiti fell from US$1.1 billion to US$947 million from 2016 to 2021. In 2019, it fell to its lowest level since 2007, at US$696 million.

Figure 2:

Text version

Figure 2:

| Official development assistance (ODA) | Disbursements ($US) |

|---|---|

USA | $2,019 |

EU Institutions | $598 |

World Bank | $596 |

IDB | $438 |

Canada | $421 |

France | $258 |

Global Fund | $203 |

Switzerland | $150 |

Japan | $140 |

United Nations | $139 |

IMF | $138 |

Source: Net ODA disbursements to countries and regions, OECD.Stat, in millions US, from 2016 to 2021.

Bilateral Relations

Canada has long-standing ties with Haiti, founded on a solidarity established by Quebec clergy and intellectuals in the early 20th century, which evolved into a formal diplomatic arrangement through the exchange of ambassadors in 1954. Cultural, academic and institutional collaborations have built the foundation for ongoing development support to Haiti. Initially shaped by the strong common influence of the Church and Francophone heritage, organic links have been facilitated by geographic proximity, the establishment of a large Haitian diaspora in Canada, especially following the Duvalier dictatorship, and the growing number of Canadian development and humanitarian organizations (NGOs) working in Haiti since the 1970s to support development efforts. At Haiti's request, Canada chairs the Group of Friends of Haiti at the Organization of American States (OAS).

Within the Americas region, Canada has invested the largest proportion of its international assistance funds in Haiti, with $88.4M disbursed in 2020 to 2021. International assistance is delivered through development projects led by implementing partners (multilateral, governmental, non-profit, institutional and private sector). Direct budget support to Haiti is non-existent.

Trade has remained modest since a first economic agreement in 2003. Canadian direct investment in Haiti is limited to the agri-food and textile sectors for import into Canada. The growth of trade links is hampered by the unstable situation, corruption and poor infrastructure.

Multilateral Relations

Canada and Haiti are both members of the OAS, the United Nations (UN), the Caribbean Community and Common Market (CARICOM), and the International Organisation of La Francophonie (OIF). Canada has positioned itself to support Haiti's needs within CARICOM, where Haiti is the only French-speaking country and the one with the largest population.

Since 1993, Canada has supported the various UN peacekeeping missions in Haiti, such as the United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH), the United Nations Mission for Justice Support in Haiti (MINUJUSTH), and since 2019, the United Nations Integrated Office in Haiti (BINUH). Canada also chairs the Economic and Social Council Ad Hoc Advisory Group on Haiti (ECOSOC-AHAG).

Canada actively participates in several donor coordination platforms in Haiti. It is a member of the CORE Group (including the Special Representative of the UN Secretary General, the Special Representative of the OAS and 7 ambassadors), created in 2004. Canada chaired the tax revenue mobilization table and co-chaired the Gender Equality Working Group with UN Women to better coordinate the work of international partners invested on gender equality (GE) in Haiti.

In 2020, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, Canada collaborated with the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) and the World Health Organization (WHO) to provide access to vaccines and deliver 180,000 doses through the COVAX mechanism.

Programming Profile

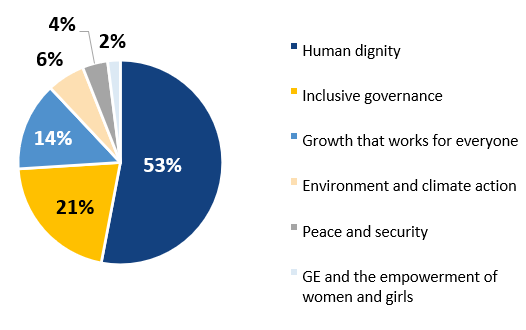

Figure 3:

Disbursements (%) by FIAP action areas, from FY 2016-17 to 2020-21

Text version

Figure 3:

- Human dignity: 53%

- Inclusive governance: 21%

- Growth that works for everyone:14%

- Environment and climate action: 6%

- Peace and security: 4%

- GE and the empowerment of women and girls: 2%

Source: CFO-Stats (2022-02-18), GAC.

Figure 4:

Disbursements (%) by type of implementing partner, from 2016-2017 to 2020-2021

Text version

Figure 4:

- Multilateral institutions: 50%

- Canadian NGOs: 33%

- International NGOs: 6%

- Private Sector: 5%

- Governmental and paragovernmental: 6%

Source: CFO-Stats (2022-02-18), GAC.

Program Disbursements

During the evaluation period, Haiti was the largest recipient of Canadian international assistance in the Americas, ranging from 4th to 13th in volume of Canadian ODA (9th in cumulative average disbursements), with a total disbursement of $436M. Four branches were involved: the Americas Branch (NGM) (66% of total disbursements), Partnerships for Development Innovation Branch (KFM) (17%), Global Issues and Development Branch (MFM) (9%), and the International Security and Political Affairs Branch (IFM) (8%). From FY 2016-17 to 2020-21, Canadian international assistance primarily funded health ($111.8M), state and civil society strengthening ($110.8M), education ($58.9M), humanitarian assistance ($46.2M) and agriculture ($26.6M).

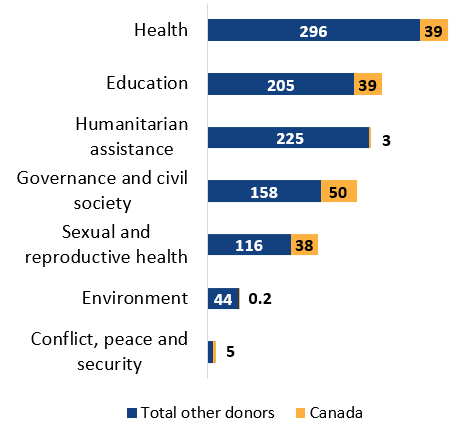

Figure 5:

Text version

Figure 5:

Banner representing the four GAC principal branches involved in Haiti’s assistance and their respective total disbursements:

- NGM: $289M

- KFM: $75M

- IFM: $33M

Americas Branch (NGM)

With average annual disbursements of $58M, NGM was invested primarily in state and civil society strengthening ($76.1M), health ($68.7M), and education ($51.9M). The most significant programmatic commitments of the bilateral program over the evaluation period were the World Food Programme's (WFP) School Feeding and Local Purchases in Haiti project for $24.7M, the United Nations Population Fund's (UNFPA) Improving Integrated Health Services for Women, Teenage Girls and Children in Haiti project for $19.6M, and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development's (IBRD) contribution to trust funds for the Improving Girls' Access to Secondary Education in Haiti.

Partnerships for Development Innovation Branch (KFM)

KFM invested primarily in health (57% of its disbursements) and agriculture (16%). The 45 projects were supported in response to multi-country calls for proposals and delivered by Canadian organizations (NGOs). KFM’s main partners in terms of financial volume were the Université de Montréal ($12M), Doctors of the World Canada ($8.8M) and Plan International Canada ($7.2M).

Global Issues and Development Branch (MFM)

This Branch primarily invested in humanitarian assistance in response to natural disasters and the resurgence of cholera, which accounted for 98% of disbursements by the sector. International assistance was deployed through support to the WFP ($18.9M), UNICEF, and Doctors of the World Canada ($5.1M each).

International Security and Political Affairs Branch (IFM)

93% of IFM disbursements were dedicated to state and civil society strengthening, primarily through the Peace and Stabilization Operations Program (PSOP), United Nations Development Program (UNDP) projects (3 projects - $8.1M), International Organization for Migration (IOM) (1 project - $6.2M), and Mercy Corps (1 project - $5.8M).

Evaluation Scope and Methodology

Evaluation Scope and Objectives

Evaluation scope

The evaluation covers Canadian international assistance programming in Haiti for the period 2016-17 to 2020-21, focusing on the latter years which were marked by significant budgetary fluctuations and structural changes. The COVID-19 pandemic at the end of the covered period, led to sudden necessary adjustments in management and programming modalities, which served to observe the program's adaptability following the evaluation. The last corporate evaluation of the Canadian program in Haiti (January 2015) covered the period from 2006 to 2013 and made 9 recommendations on programmatic direction and consolidation, sustainability, environmental sensitivity, support to state structures, and capacity to demonstrate results.

A sample of 42 projects implemented by 36 partners representative of the four program areas and diversity in partner typology served as the basis for the literature review. The evaluation did not cover humanitarian programming in depth, which has largely been implemented through multilateral agencies; nor the PSOP program in Haiti, which has been the subject of a recent in-depth case study.Footnote 4

The evaluation covers official development assistance (ODA) disbursed mostly through four branches of Global Affairs Canada (GAC) over the period: the Americas Branch (NGM), Partnerships for Development Innovation Branch (KFM), Global Issues and Development Branch (MFM) and International Security and Political Affairs Branch (IFM).

Objectives

The purpose of the evaluation is to determine the extent to which Canada's international assistance to Haiti has been adapted to the country's priorities and has used optimal intervention strategies and modalities to advance its objectives, given the context of persistent fragility during the period.

It serves a substantial formative evaluation, with findings and recommendations that could lead to better targeting of Canada's role in international cooperation in Haiti and to improved programming, management and coordination within and across GAC programming streams in the country.

Evaluation approach

The evaluation was conducted by the Evaluation Division (PRA), with the support of an external consultant to conduct two case studies. Initially scheduled for approval in 2020 as per the Five-Year Departmental Evaluation Plan from 2020-21 to 2024-25, the evaluation of Canada's international assistance program in Haiti was postponed for one year and then launched in February 2022. It was preceded by an evaluability analysis conducted from November 2021 to January 2022.

The evaluation focused on five of the OECD's Development Assistance Committee (DAC) criteria for evaluating development assistance: relevance, efficiency, internal and external coherence, and aspects of the impact of Canada's international assistance program in Haiti. It examines programmatic results with a view to support the implementation of Canada's new Haiti program strategy (FY 2021-22 to 2027-28).

Evaluation Questions

| Evaluation issue | Priority topics | Questions |

|---|---|---|

Relevance |

| Q1. To what extent was international assistance adapted to the priorities and context of fragility in Haiti? Were the causes and vulnerabilities that determine poverty adequately addressed? |

Efficiency |

| Q2. Have international assistance delivery mechanisms been optimal for achieving results? |

Coherence (internal) |

| Q3. What is the level of coordination and collaboration between GAC's development, security and humanitarian response programs in Haiti? |

Coherence (external) |

| Q4. What has been the impact of Canada's Feminist International Assistance Policy in relation to major donor priorities since 2015? |

Q5. What is the value of Canada's collaboration among donors in supporting humanitarian, peace and security, and development objectives and initiatives? | ||

Impact |

| Q6. In what ways do the lessons learned over time from the Haiti international assistance program inform the current program strategy? |

Methodology

The evaluation used a mixed-methods approach and data collected from diverse sources were triangulated using five methods:

Document Review:

Analysis of Global Affairs Canada internal documents:

- strategic, policy and operational planning documents;

- statistical data (CFO stats, partner portal, etc.);

- briefing notes and memos;

- evaluation report;

- annual reports;

- project documents.

Literature Review

Analysis of external documents:

- scholarly articles;

- research reports and technical notes; and

- other, such as media publications, websites and fact sheets.

Case studies:

- Governance: analysis of Canada's interventions in governance in Haiti (at various state, municipal and CSO levels) with a view to assess the success factors, impact, and challenges encountered.

- Meta-analysis of decentralized evaluations conducted during the period that covered a variety of sectoral initiatives, to highlight the cross-cutting findings and lessons learned informing programmatic results.

Focus Groups

Two focus groups were conducted with implementing partners selected on the basis of their initiatives in Haiti on governance and agriculture and rural development (N=11 partners in total).

Semi-structured Key Informant Interviews

Semi-structured individual interviews (N=57) with various internal Global Affairs Canada stakeholders and external stakeholders:

- NDH and NGM staff (N=10);

- Global Affairs Canada staff from other branches (IFM, KFM, MFM, DPD, SCM, BSD) (N=9);

- staff present and previously based at the mission (NCCP) (N=12);

- representatives of partner organizations (N=12);

- staff affiliated with the Government of Haiti (N=8);

- Canadian programming consultants and experts in Haiti (N=6).

Evaluation Limitations and Mitigation Measures

| Limitations | Mitigation Measures |

|---|---|

Availability of respondents The deteriorating political and security situation in Haiti has hampered the availability and willingness of many of the respondents in Haiti with whom the evaluation team had originally planned to hold discussions. |

|

Data availability Timely availability of program data from the Geographic Bureau was not optimal. Financial, human resources, and selection mechanism information could not be obtained, either because of shortcomings in information management, or because of workloads linked to the crisis in Haiti during the period. |

|

Inability to collect data in the field The precarious security situation in Haiti since 2021 prevented the evaluation team from visiting the country to observe, conduct individual interviews and facilitate face-to-face discussion groups. |

|

Relevance of findings to the current context The political, security, and development context in Haiti changed significantly as of 2021. As the evaluation covers the five-year period 2016-17 to 2020-21, most evaluation findings are based on GAC's programming prior to the crisis and the current context. The relevance of the findings can therefore not exhaustively reflect the development assistance issues brought about by the country's chaotic context since 2021. |

|

Findings: Relevance

Responding to Haiti's needs and priorities

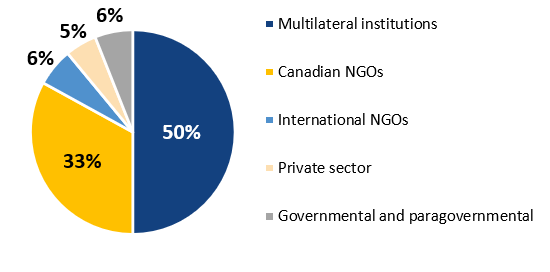

Figure 6:

Net ODA (grant) disbursements by sector of intervention in Haiti, in millions US dollars, from 2016 to 2020

Text version

Figure 6:

| Sector of Interventions | Total other donors (million $US) | Canada (million $US) |

|---|---|---|

Health | 296 | 39 |

Education | 205 | 39 |

Humanitarian assistance | 225 | 3 |

Governance and civil society | 158 | 50 |

Sexual and reproductive health | 116 | 38 |

Environment | 44 | 0.2 |

Conflict, peace and security | 7 | 5 |

Source: Aid Atlas, Stockholm Environment Institute (SEI), 2019.

The broad range of priorities in Haiti's Strategic Development Plan (PSDH) has allowed for a default alignment of Canadian international assistance.

In 2012, the Haitian government adopted the PSDH, which sets out a long-term vision for the development of the country, in the context of recovery from the 2010 earthquake, in four major areas (territorial, economic, social and institutional) and their 32 programs. The plan aims to achieve a more just and egalitarian society, where the needs of the population are met through economic development, the restructuring of state institutions and the leadership of a strong and responsible state. From 2016 to 2021, Canadian international assistance planning in Haiti has not been subject to a deliberate and systematic exercise of alignment with the PSDH. In a ministerial statement in 2018, the principles that would guide Canada's engagement in Haiti were set out: "Canada is accompanying Haiti on its path to economic emergence. Under Haitian leadership and with the increased participation of women, Canada is helping to strengthen governance and the rule of law and improve the quality of life of the poorest in ways that increase the confidence of the people, partners and investors." The profile of Canadian international assistance has demonstrated a de facto alignment with mostly social and institutional priorities due to the broad range of priorities of the PSDH rather than through strategic consultation with the Haitian state. The high level of Canadian funding to multilateral agencies and multi-donor initiatives has reinforced alignment in that these initiatives fit within the priorities identified with the Haitian state.

Canadian international assistance has been guided by departmental commitments and by Canada’s Feminist International Assistance Policy (FIAP) rather than by a country programming strategy.

A country strategy for the Haiti program was only developed at the end of the period, in 2021. During the five years covered by the evaluation, Canadian programming did not have an articulated long-term programmatic frameworkFootnote 5 and rather focused on responding to departmental commitments (Maternal and Child Health program from 2016 to 2021; "Her Voice Her Choice" from 2017 to 2020; "Women's Voice and Leadership" from 2017 to 2021). Programming remained largely in line with the historical continuity of Canadian international assistance, but with an even stronger focus on the health of women and children in particular. Within the FIAP's action areas, investments in the area of human dignity were characterized by a significant component of direct service delivery in health and education. The relevance of these investments was apparent, as only 4.7% of the Government of Haiti's budget was allocated to health between 2016 and 2020,Footnote 6 with Haiti listed last out of 34 countries for health investments in 2017.Footnote 7Increased investment in health initiatives resulted in a shift in funding, with decreasing funds allocated to environmental protection and climate change adaptation programming by 33% (compared to the 2011 to 2015 period). This shift signaled the dilemma of investing in long-term systemic change objectives in favor of shorter-term projects targeting vital service programming. This is a particularly persistent challenge in fragile states, where these difficult choices have to be made. The inclusive governance sector saw a modest increase of 4% over the previous period. The chaotic governance context and the instability during the period were reflected in the programmatic choices, with a tendency toward meeting basic needs.

Consideration of the causes of vulnerability

The Pressure and Release Disaster (PAR) model explains disaster as the interaction between social, economic and actual natural disaster factors (type, intensity, density).

Using the PAR model, Anthropologist Mark SchullerFootnote 8 analyzed the situation in Haiti as follows:

- fundamental causes (political and economic systems and structures of power and wealth distribution; economic exploitation, colonial legacy, foreign interference),

- dynamic pressures: consequences of poor social and economic functioning (overcrowding, poor and outdated infrastructure, deforestation, rural poverty and urban migration), and

- the dangerous conditions that constitute society's vulnerability (poorly constructed and localized buildings, waste and unsanitary conditions, poverty and despair installing violence).

"Building back better is not just a matter of changing the unsafe conditions (...) but things need to be changed on a deeper level as well. Change the unsafe conditions, reduce the dynamic pressure and attack the root causes.”Footnote 9

The results-based program framework allowed for flexibility in project implementation, but actions were decided in response to events rather than as part of a risk management strategy.

A thorough analysis of vulnerability issues and the causes of gender inequality was not done at the program level in support of the objectives of Canada's National Action Plan on Women, Peace and Security (NAPWPS). Analysis could have better targeted the integration and planning of gender equality (GE) work across all of GAC's spheres of action, including sectoral analyses, as the basis for a programmatic strategy on GE.

While GAC has indeed shown flexibility when conditions and events posed significant challenges to project implementation, the program as a whole has shown little evidence of a strategic approach to risk management and mitigation. This was evident in the case of environmental risks associated with the natural disasters that the country suffered recurrently over the past decades. While the environmental impact criterion was included in the project proposal modalities, the considerations were limited to the plausible impact and mitigation of the initiative itself: the Canadian program did not develop a strategic analysis on broader environmental issues impacting development efforts in Haiti, which could have identified trends, means and opportunities for Canada to address these challenges in a programmatic approach.

The absence of a strategic planning exercise at the country program level until late in the period and the low level of introspection of the lessons learned by GAC from events and projects were some of the factors inhibiting the consideration of the causes and risks of vulnerabilities from a broader perspective than on the basis of singular projects.

Nevertheless, at the activity level, several partner initiatives were designed with a strong climate change resilience objective. These projects included risk mitigation and prevention components (agricultural sector and adapted transformative technologies; agricultural insurance; production methods and inputs with high resistance to natural disasters, etc.), but the level of risk of natural disasters and their impacts would have justified both a programmatic vision and a longer-term commitment on the part of the Government of Canada to better ensure the preservation and longevity of development gains.

Findings: Efficiency

Partner Selection: Mechanisms and adaptation

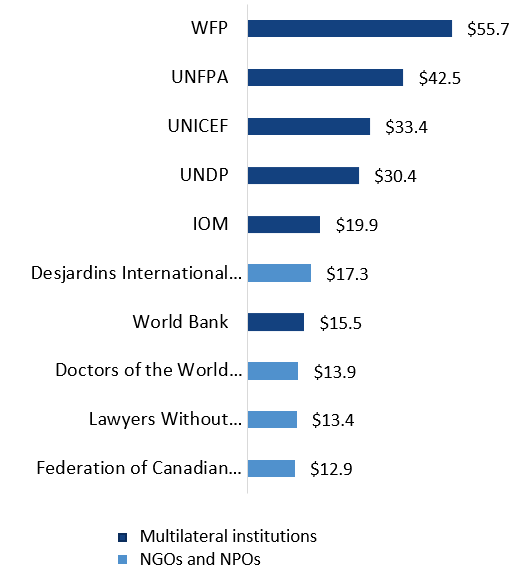

Figure 7:

Top partners of Canadian international assistance to Haiti, in millions of dollars, from FY 2016-17 to 2020-21

Text version

Figure 7:

Multilateral institutions:

- WFP: $55.7M

- UNFPA: $42.5M

- UNICEF: $33.4M

- UNDP: $30.4M

- IOM: $19.9M

- World Bank: $15.5M

NGOs and NPOs:

- Desjardins International Development: $17.3M

- Doctor of the World Canada: $15.5M

- Lawyers Without Borders Canada: $13.4M

- Federation of Canadian Municipalities: $12.9M

Source: CFO-Stats (2022-02-18), GAC.

The efficiency of partner selection was adapted to the context.

Canada delivered the program through 38 Canadian and 29 international non-profit organizations (NPOs), including 17 multilateral executing agencies. The latter received 50% of total disbursements and 59% of NGM disbursements. The 38 Canadian NPOs received 33% of the funding, including 29% of bilateral funds and 99% of KFM funds. The Canadian NPOs, the majority of which were long-established in Haiti, had a history of programming with the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) and GAC. Project report reviews and decentralized evaluations showed that these partners brought a solid knowledge of the country's issues and of their geographic areas of intervention, as well as an extensive network of local contacts through their direct work with Haitian communities and civil society organizations. According to several respondents, this enabled activities to be started up and resumed following interruptions efficiently, despite delays in approvals (at the level of GAC and/or the supervising state structures). Multilateral agencies, for their part, had a broader coverage both geographically and thematically, and a strong capacity for resilience in the context of multiple vulnerabilities, but less solid roots at community level, particularly for post-project ownership and continuity.

The department-initiated mechanism for project selection by the Haiti Division (NDH) has been largely adapted to the partnership with multilateral agencies, but the Feminist International Assistance Policy (FIAP) agenda was therein diffused.

The high number of projects carried out by multilateral agencies (comparable to disbursements in highly vulnerable countries) explains the predominance of the department-initiated selection mechanism (52% of projects and 13 department-initiated initiatives). From 2014 to 2021, there were 3 calls for proposals by NDH that generated few projects: Women as agents of change in the Americas in 2019 (3 proposals, no approvals), Improving Citizen Participation in Haiti’s Health Sector in 2018 (14 proposals, 2 approvals), and Strengthening Agri-food Value Chains and Adaptation to Climate Change in 2017 (24 proposals, 4 approvals). In this context, the department-initiated mechanism targeted more effectively and efficiently recognized development priorities in Haiti, but limited the level of prioritization and intensity of work on GE as multilateral partners framed their commitments around broad national priorities. While GAC benefited from multilateral project administration (rapid project start-up and efficiency in management), these partners and projects were not designed to provide GAC-specific results reporting aligned to the FIAP, making it difficult to measure the extent of those projects’ contribution to priorities of the Government of Canada.

Calls for proposals made by the Partnerships for Development Innovation Branch (KFM) generated projects that met departmental priorities but were sometimes slow in moving to implementation.

Eight calls for proposals were issued between 2014 and 2021 by KFM for multi-country programming, stemming from thematic ministerial commitments, especially in health. Twelve of the 18 projects selected from these calls started during the period: while the calls for proposals were effective in selecting the partners and projects best aligned with the themes, the processes were unpredictable in their duration and associated administrative complexity.

Partner Selection: Focus of the FIAP

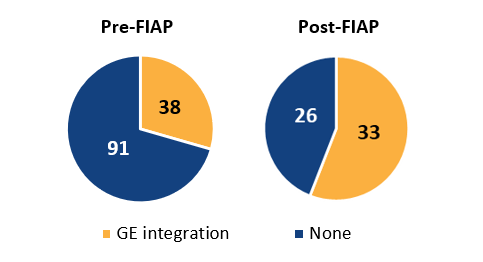

Figure 8:

Level of substantive GE integration (by number of projects), from FY 2016-2017 to 2020-2021

Text version

Figure 8:

Pre-FIAP

- GE integration: 38

- None: 91

Post-FIAP:

- GE integration: 33

- None: 26

Source: CFO-Stats (2022-02-18), GAC.

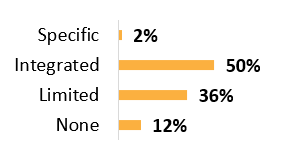

Figure 9:

NDH GE integration (FY 2016-17 – 2020-21)

Text version

Figure 9:

- Specific: 2%

- Integrated: 50%

- Limited: 36%

- None: 12%

Source: CFO-Stats (2022-02-18), GAC.

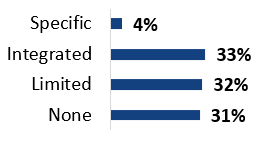

Figure 10:

Total GE integration (FY 2016-17 – 2020-21)

Text version

Figure 10:

- Specific: 4%

- Integrated: 33%

- Limited: 32%

- None: 31%

Source: CFO-Stats (2022-02-18), GAC.

Delays in closing the selection and contracting processes adversely affected project plans, management, and partnerships.

Rigorous selection processes ensured the selection of projects and implementing partners with good technical and fiduciary capabilities. However, the time lag between proposal submission and project start-up (1-4 years for 5 calls for proposals) created challenges for many partners in terms of planning, human resource retention, budgeting, and linkages with local communities and partners that hindered timely responsiveness to needs. The same is true for the extension of projects: long delays before confirmation affected the maintenance of management structures, ongoing links with beneficiaries and the stability or even feasibility of the project (e.g. PCM, Vivre ensemble, PRISMA). Decision-making delays hampered opportunities for additional funding or expansion (e.g. PCM, suite de PIRFH, PRISMA).

The adoption of the FIAP and its implementation in the Haitian context and program raised several types of challenges despite some observable gains.

The lack of a long-term perspective on GE work in Haiti, which would have focused on an analysis of GE issues specific to the context of prolonged crises, limited the strategic perspective in support of the FIAP. The Policy and its aims were inserted into the program in a reactive manner, resulting in little coherence and limited vision on priority and strategic issues that could help maximize results. The approach to GE was considered on the basis of singular projects.

The selection of projects from 2017 onwards was indeed made with specific attention to the integration of GE. Thus, the proportion of projects substantially integrating the GE increased from 29.5% before the adoption of the FIAP to 55.9% for projects after June 2017. Several partners aligned their projects more strongly with strengthening GE – which was an opportunity for some, and a more demanding adaptation for others. There was a very mixed reception of FIAP from several state partners as well as at community level where traditional roles and power dynamics manifested in resistance to prioritizing efforts toward GE. It should be noted that the rating system and coding by priority action area did not provide an accurate profile of GE work. Policy implementation was slow to translate into projects on the ground, interpreting a rating on existing projects was complicated, and projects with a significant GE dimension were categorized in different action areas.

Partners faced both existential and operational challenges, citing, for example, the difficulty of planning transformative systemic projects (rated EG-3) that were rightly or wrongly perceived as prioritized by GAC, in a social and institutional context with unfavorable traditions. Respondents complained about the late availability of resources to support the implementation of the FIAP, the varying interpretations of expectations provided by GAC and the coding system.

However, notable gains were identified. For instance, projects that did not specifically target gender mainstreaming still developed tools to measure their gender outcomes as a result of gender-based analysis (GBA Plus) (e.g. UNICEF; Equitas). The “positive masculinity” approach shared by 5 MNCH projects aimed at engaging men resulted in, among other things, increased support from men to women in their decision to use MNCH services, and increased recognition of women's rights in the project areas.

Structure and Human Resources

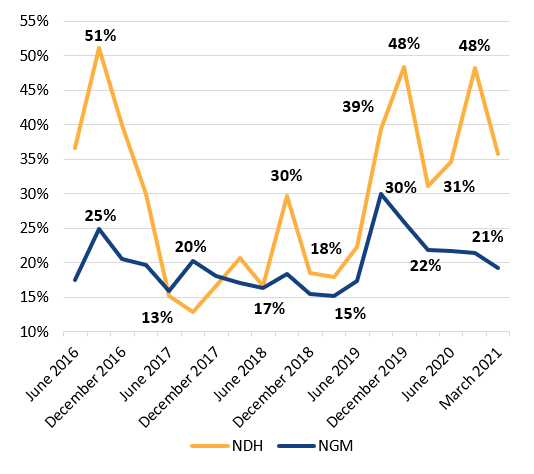

Figure 11:

Vacancy rate (%), quarterly change, from FY 2016-17 to 2020-21

Text version

Figure 11:

NDH

- September 2016: 51%

- September 2017: 13 %

- June 2018: 17%

- September 2018: 30%

- March 2019: 18 %

- September 2019: 39 %

- December 2019: 48 %

- March 2020: 31 %

- September 2020: 48 %

NGH

- September 2016: 25%

- September 2017: 20%

- March 2019: 15 %

- September 2019: 30 %

- March 2020: 22 %

- September 2020: 21 %

Source: HR Data from Power BI, GAC, February 2023.

The constant challenges of crisis management in a context of limited human resources prevented strategic planning until the last year of the period covered.

The first recommendation of the Evaluation of Canada-Haiti Cooperation 2006-2013 was the development of a country framework that takes into account the Haitian government's priorities and update the sectoral strategies. The Strategy for Canada in Haiti was developed and adopted in January 2021. In the absence of a medium- and long-term strategic vision, the program and its staff had to deal with crisis after crisis in reactive mode, a situation that affected the attractiveness of potential staff to the program. The consequences of crisis management on human resources were evident in the loss of institutional memory at the staff and bureau levels. All of these conditions were therefore not optimal for strategic management based on built knowledge and planning.

Significant human resource challenges (recruitment, retention, and expertise) disrupted the management of the Haiti program (NDH) at HQ and at mission.

The Haiti Geographic Bureau had, almost consistently over the period, problems with recruitment and retention of staff. This affected management and programming capacity due to the volume of work to be distributed over a limited staff contingent, especially taking into account program needs and disruptions. Frequent changes in senior decision-making positions, according to a majority of respondents, affected the stability of the management approach and the ability to develop strategic programming with a clear vision supported by all program stakeholders.

The quarterly vacancy rate within NDH from June 2016 to March 2021 showed significant fluctuations (between 13% and 51% with an average of 30%) and was the highest in the Branch (NGM average of 20%). Due to changes in budget allocations, the number of positions also dropped from 40 in 2016 to 25 in March 2021. This resulted in a loss of stability, gaps in expertise and experience level, and a disruptive situation of managing in crisis mode, while the number of projects to be managed over these years remained stable.

At the mission level, the number of positions were fairly stable for both Canadian and local positions. However, even at the mission, there were vacancy percentages ranging from 10% (2016) to 43% (2021). Security challenges and the difficulty of attracting qualified rotational staff have increased since 2015. Important decision-making positions were not always filled with staff with the appropriate expertise for the context and needs. Stable local staff played an important role in monitoring mission activities both during periods when several Canadian positions remained vacant and during crisis situations when evacuations were required.

The demand on management was thus exacerbated by the cumulative effects of three disruptive factors: the level of unfilled positions, the frequent staff turnover limiting the contribution of experience to a complex program, and the level of instability in Haiti increasing crisis management pressures, both at HQ and at the mission.

Operation and Program Monitoring

Opportunities to strengthen linkages between Canadian initiatives and to network with donors were missed.

From the point of view of several respondents, the mission, while providing ad hoc support, did not actively play a catalytic role between Canadian project partners and between partners and other donors. This could have leveraged Canadian programming, increased funding and extended strategic projects. Projects that had built strong networks between various sectors, such as the PIRFH project with its network of Canadian partners (Union of Quebec Municipalities, chambers of commerce, City of Montréal, etc.) and its extensive networking with donors such as the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), USAID, and the UN in the field, could have been accentuated and expanded by a commitment from the mission in support of these potential leverage effects.

Several respondents also pointed out that the roles and responsibilities between HQ and mission were not always applied in a way that maximized benefits to the program and the various partners. Decisions made at HQ sometimes clashed with the reality on the ground, lacked systematic and timely context analysis, and did not reflect a proactive role by GAC in creating spaces for regular collaboration among partners.

Modalities for monitoring and evaluating programming were uneven and insufficient to adequately extract lessons for program improvement.

Program monitors assigned to monitor certain projects, and the field monitoring by experts attached to the Field Support Services’ Project (PSAT), generated useful reports for the program. However, other factors hampered monitoring capacity, including the insecure context limiting visits to the regions, vacancies affecting staff capacity, and the high level of solicitation for external support that PSAT received. In contrast to the former Project Support Unit, PSAT offered experts who were often called upon by other donors or mobilized to provide information to headquarters, and therefore had limited availability. PSOP assigned a project officer at headquarters and a political attaché at the mission as a focal point officer, but the local officer had neither the mandate nor the expertise for PSOP technical monitoring and inter-donor coordination on peace and security in Haiti. The PSAT did not have a formal role in supporting PSOP, which limited Canada's engagement and visibility in the field.

In addition, the management summary reports (MSRs) prepared by project officers based on partner reports were poorly aligned with the department's key performance indicators, and were of little use in extracting meaningful lessons from experiences to improve programming. The limited availability of project officers to distill lessons learned and disseminate project learning meant that knowledge useful for future programmatic directions and decisions did not circulate as much as it could have and did not feed much into collective thinking on strategic directions.

Ability to adapt programming

Figure 12:

Text version

Figure 12:

Quote in a bubble: "Partners were creative and innovative in the face of limitations and continued insecurity. For example, WFP explored new ways to transport food by boat, as roads were constantly blocked by gang violence. Canada has also funded helicopter transportation. In Haiti, alternatives must be explored." - Mission staff member

Figure 13:

Text version

Figure 13:

Quote in a bubble: "The project was implemented effectively and efficiently. However, when it came time to get an extension, at GAC's own request, the bureaucratic machinery was too slow. Things had to move or we were ready to leave. As long as there is no signature, we cannot continue. We were in the process of packing up when the confirmation was finally made."- Partner NPO

Selection and contracting processes did not facilitate the need for rapid adaptation to the Haitian context, particularly given the differing standards between the mechanisms favored by various branches.

The selection process for development projects was lengthy and its bureaucratic complexity posed significant challenges for many partners in this stream. This was not the case for humanitarian projects, according to the testimonies of partners who received funding from both sources. Both the humanitarian sector and PSOP have had faster and more efficient selection and contracting processes. The ability to easily interweave a development project following, for example, the end of a humanitarian response, was limited by these separate standards. In the case of extended waiting periods reported by a number of partners, plans were eventually adapted, although the elapsed time sometimes resulted in several iterations of proposals and back-and-forth negotiations with program management at GAC, limiting efficiency and creating unduly idle periods between initiatives that should have smoothly followed one another.

GAC programming was able to draw on the experience of local partners and staff at mission to ensure continuity and adaptation during disruptions.

Partners with experience in Haiti and extensive experience working at the local and regional level had contingency planning practices in response to situations of fragility. These partnerships, along with the stability of local staff at mission, were factors that facilitated resilience and adaptation to crisis situations.

The results-based program framework was a factor in facilitating adjustments to projects when necessary.

The results-based programming framework allowed for adjustments to activities and timelines in ongoing projects, which was useful during natural disasters, the COVID-19 pandemic, and in the context of increasing insecurity. Several partners spoke of the impact of frequent contextual changes in Haiti on their ability to carry out their activities as planned, noting that, in addition to their knowledge of the terrain, GAC's flexibility in adapting projects helped them operate through constraints and achieve some results.

Measures taken by GAC at the time of the pandemic, both to adjust project activities and monitoring (reporting, delegated decision making, reallocation of funds, support for telework, etc.), were effective and appreciated, demonstrating that the flexibility then applied can simplify program operationalization. On the other hand, physical adaptations that would have facilitated the teleworking of local partners could not be implemented due to lack of budget and essential logistical conditions, with the result that program elements had to be interrupted or cancelled.

Findings: Internal Coherence

Triple nexus

Haiti is the most vulnerable country in the Americas. This context calls for an intentional triple nexus approach to maximize the coherence and impact of Canada's international assistance.

While some bridging initiatives demonstrated a willingness to connect more closely, to date the various sectors (development, humanitarian, peace and security) had few opportunities and mechanisms to work collaboratively and generally operated in silos, without a shared vision or aligned objectives.

There was no cross-functional planning process that would have gained the collective buy-in of the divisions involved in Canadian international assistance and fostered the organization of work across divisions, leverage between programs, and logical and timely transitions between initiatives.

In a context of fragility and protracted crisis such as in Haiti, a programming framework based on vulnerability and risk management would be a sound basis on which to design a unified plan that brings all sectors together under common objectives. It lacked corporate incentives and the management structure did not optimally lend itself to a true triple nexus approach.

Despite an observable convergence of interventions between the development program and PSOP, the program channels paid little attention to collaboration and complementarity that could have supported their efficiency.

As mentioned in the March 2020 PSOP monitoring report,Footnote 10 13 development program projects ($62M in disbursements) focused on themes common to PSOP (human rights, women's rights, justice, police, elections, transparency and local governance). There was also a convergence of partners or beneficiaries between the development program and PSOP: the projects Supporting and Reinforcing the Establishment of the Haitian National Border Police (PSOP), Assisting Vulnerable Children and Women in Haiti's Border Areas (NDH), and Relocation and Support Program for Displaced People in Haiti (NDH) all had IOM as an implementing partner, while the projects Improving the Integration of Women in the Haitian National Police (PSOP), and Initial Training and Professional Development for the Haitian National Police's Managerial Staff (NDH) both targeted the strengthening of the Haitian National Police (PNH). Despite these intersections, the development program appeared to be unfamiliar with PSOP activities and the Integrated Peace and Security Plan for Haiti (IPSP), to which NDH nevertheless contributed through consultations. The plan was seen singularly as the PSOP plan, despite the alignment of its objectives with the goals of GE programming.

The humanitarian-development nexus was often an operational challenge in coordinating emergency response and the resumption of development initiatives, but the alignment of partners helped coordination and transition.

Coordination between the humanitarian and bilateral programs was achieved primarily through the funding of complementary initiatives implemented by the same partner. The WFP received 49.7% of the humanitarian funding from Canada that implemented the School Feeding and Local Purchases in Haiti project on behalf of the development program. During Hurricane Matthew, discussions between the humanitarian program and the development program made it possible to make food stocks available in school canteens to meet the urgent needs of disaster victims. The humanitarian program's grant then replenished the school feeding project's stocks. The two programs also provided complementary funding to UNICEF: the fight against cholera and the Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) in the Artibonite and Centre Departments of Haiti. Doctors of the World Canada partnered with both a development project funded by KFM and a humanitarian response to Hurricane Matthew. However, despite the ability of some partners to carry out programming in multiple streams, continuity over time between the end of humanitarian interventions and the resumption of development projects was not assured. Some factors were longer approval times for bilateral projects than for humanitarian projects, for example, and the fact that the required interventions were not planned with a broader perspective than what each sector covered in its own modalities. This was also problematic following the recovery from Hurricane Matthew. Leveraging from one program to another was therefore not always maximized.

Findings: External Coherence

Canada’s role among donors

Figure 14:

Text version

Figure 14:

Picture of CARICOM Committee of Ambassador Meeting in May 2018.

Photo credit: CARICOM, May 2018

Donor coordination was more effective at the political level than at the operational level.

Canada played an active role in the group of major bilateral and multilateral donors in Haiti (the "CORE group") and worked continuously to build consensus among donors. In the context of the multi-dimensional crisis, donor coordination and consensus remained essential to streamline actions. Donor coordination at this level was aimed at collectively seeking solutions to restore a functioning democracy in Haiti. Canada has been increasingly active on the Group of Friends of Haiti at the OAS. Canada's voice at the diplomatic level became more important over the period.

At the operational level, a few mechanisms fostered some coordination between development interventions, notably thematic tables, but they were unevenly active and were used more for information sharing (Canada co-chaired the Gender Equality table and chaired the Tax Revenue table under the Public Finance group). There were examples of complementarity between Canadian and other donor interventions, such as the US funding of the Haitian National Police School and Canada's funding of the National Police Academy (NPA), both of which ensure a continuum of police training in Haiti. Joint funding also supported the strengthening of the border police, in collaboration with the IOM. Inter-donor coordination was also quite functional in humanitarian responses under the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs following natural disasters during the period. The broad interventions of co-funded multilateral partners were an asset for external coherence and were part of a negotiated strategy in the humanitarian and security context mainly.

However, the lack of dedicated mission resources to enhance Canada's engagement on the ground in various policy forums, as well as the reluctance of individual donors to share information on their interventions, limited the potential for inter-donor collaboration, particularly in the development stream. There were distinctions in the geographic areas of donor intervention, but even that complementarity remained unclear and informal.

Canada continued to play a leadership role as an international assistance partner in Haiti, in regional institutions and at the United Nations.

Canada supported several initiatives for Haiti within CARICOM, the Caribbean Development Bank (CDB) and the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) and advocated for stronger support for Haiti from these institutions. This translated into projects for access to basic education, including earthquake resistant infrastructure and access by Haiti to CCRIF SPC insurance payments (a CARICOM and IDB mechanism) through Canada's contribution to the multi-donor fund following Hurricane Matthew. Canada played an important role in the design and implementation of multi-donor funds, including the UN Common Security Fund and the Southern Reconstruction Fund, which allowed Canadian international assistance to have a broader impact than individual projects, thanks to the collective approach coordinated by the UN (OCHA and UNDP). Haiti relied on and recognized Canada's support at these regional tables.

Results: Gender Equality

Figure 15:

Text version

Figure 15: Picture of a workshop taking place in Les Palmes, Haiti.

Photo credit: Lucie Goulet, Les Palmes, Haiti, 2016.

Canada distinguished itself as a leader on gender equality (GE) among donors.

GAC staff raised the level of consideration of GE at sectoral working tables and influenced its inclusion in multilateral or co-financed interventions. The FIAP was adopted in 2017 and, as a result of implementation deadlines, most of the projects approved under the FIAP were approved towards the end of the period between 2019 to 2021. It was therefore premature to conclude on results over such a short period. However, GE was already a cross-cutting theme of CIDA's Gender Equality Policy (2013) and a priority in the period prior to the FIAP. From 2016-17 to 2020-21, GAC worked to strengthen the GE policy framework at the national level by supporting, through the PARGEP and PATH projects, the design of MCFDF's Gender Equality Policy (2015) and its Action Plan, and by co-chairing with UN-Women the Gender Equality Partners Working Group (2017).

The integration of GE was subject to various interpretations and uneven consideration in projects, but more importantly, was not strategically planned at the program level.

Some partners developed a GE strategy and conducted Gender-based Analysis Plus (GBA Plus), used to refine initiatives. For example, the FIPCA-PNH project focused on reducing biases that limit women's access to policing; human rights education projects also began with a gender-based analysis. However, most projects addressed gender equality issues on the surface in Haiti. Few solid preliminary analyses using GBA Plus were done, with partners planning at the outset strengthening and awareness-raising activities or service delivery to meet the practical needs of women and girls. As illustrated in reports, indicators were largely based on counts of activities and participants. The predominant approach to GE focused on increasing the number of women beneficiaries was scarcely strategic in view of transforming gender-based power relations. This finding illustrates the complexity of GE work in a context where cultural, social, and political barriers to empowerment were considerable, and stresses the limitation of a project approach to foster systemic change. The finding on GE outcomes compares to that of the previous evaluation of the Haiti program (2006-2013), where the "lack of an effective performance measurement system" makes it impossible to identify outcomes beyond outputs for almost all projects.

In targeted programming for Women's Voices and Leadership in Haiti, the "Pou Fanm Pi Djanm" project supported 30 women's rights organizations with rapid funds for training on women's rights. The Reducing Violence Against Women Politicians in Haiti project was able to train 272 potential women candidates for political leadership. However, at this stage, there is also a lack of data demonstrating results beyond outputs.

Overall, monitoring of results after a project began was weak. Three observations about the integration of GE emerged from the meta-analysis of decentralized project evaluations: some projects developed strategies on GE but did not implement them (PAMREF) or allocate funds to them (Support to the Electoral Process in Haiti), others collected baseline data on GE but did not use them (Support to Local Governance and Territorial Development and Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene), while others achieved some GE outcomes without planning a strategy to do so (empowerment of women farmers through the SYFAAH project).

Results: Health – Education

Figure 16 :

Text version

Figure 16: Picture of a Doctor of the World Canada with a family in Haiti.

Photo credit: Doctors of the World Canada.

Significant programming in maternal and child health reported positive output results but were structurally weak and of questionable sustainability.

Health programming in Haiti was dominated by five projects from KFM's call for proposals for the Partnership for Maternal, Newborn, and Child Health (PMNCH) for a total of $31.6M versus $24.7M invested by NGM. The interventions targeted at the Haitian government’s administrative department level carried out most of their activities and obtained positive outputs, but the results were difficult to measure due to the lack of baseline data and the weakness of maternal and child health indicators at the departmental level. According to the evaluation, positive results in strengthening the technical and material capacities of the supported health structures were observed to some extent, but the sustainability of these gains is questionable without continued support. The mixed performance was attributable to the uneven expertise of the partners in health governance and the moderate commitment of certain Directions of health departments. In addition, minimal engagement with authorities of the Ministry of Health (MSPP) at the central level further reduced potential of continuity and follow-up.

NDH managed significant health programming, but the potential for sustainability of interventions were equally limited.

GAC made a significant commitment with the Call to Action for Robust Canadian Cooperation for Haiti's Health System (2018), including its major partners working in health. This included two 5-year projects (SSIAF, Midwifery Support) among others. The PRISMA 2 project ($19.5M), was working with the Artibonite Departmental Health Directorate since 2017 to reduce the high maternal mortality rate and reported an increase in attendance at health facilities for deliveries, use of sexual and reproductive health services, and improved nutritional monitoring of children. The Directorate performed among the best in managing COVID-19, and integrated gender issues into its plans and reports.

NDH health programming targeted other health sub-sectors, including water, sanitation and hygiene. Results in this area were limited: the number of households and schools with safe water and sanitation facilities increased, but most ceased to be functional. There was no mechanism for ongoing maintenance of these water points, and the weak monitoring system did not allow for the raising of awareness and the mobilization necessary to organize for beneficiary takeover of the infrastructure.

Education initiatives effectively supported school feeding and facilitated girls' access to secondary education: reports showed positive results, but initiatives remained donor dependent.

There were 26 education projects totaling $58.9M (NDH: $51.9M; KFM: $4.9M). WFP's School Canteens and Local Procurement ($23.2M) and Support to School Canteens in Haiti ($4.5M) projects aimed to keep children in school and improve their nutrition, and to develop a National School Feeding Policy and Strategy with MENFP. Results remained largely dependent on continuity of funding. There was no possible assessment of results of the Improving Access to Secondary Education for Girls (IBRD) project, which was active at the end of the evaluation period.

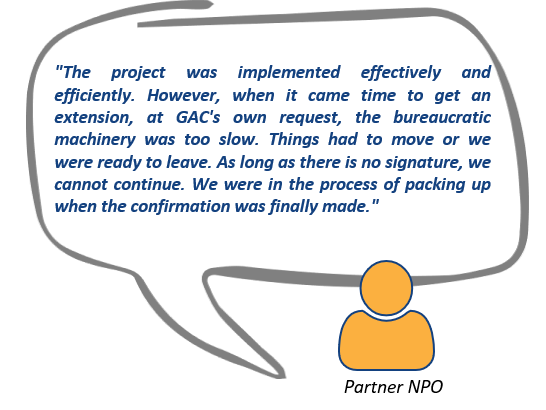

Results: Governance

GAC made significant contributions to the goal of improving governance, including projects to restore the rule of law, cross-cutting governance initiatives (strengthening central and decentralized state structures), and economic governance projects to increase revenue generation capacity at the state level. These 3 sectors disbursed $82.7M. Total governance disbursements for the period 2016-17 to 2020-21 were $90.3M.

Figure 17:

Disbursements by governance sub-sectors, in millions of dollars, from FY 2016-2017 to 2020-2021

Text version

Figure 17 :

- Democratic processes: $1.6M

- Human rights: $2.4M

- Support to civil society: $3,6M

- Economic governance: $14.3M

- Cross-sectional governance: $33.2M

- Rule of law: $35.2M

Source: CFO-Stats (2022-02-18), GAC.

Canadian investments in decentralized governance strengthened local management and governance structures and community participation.

The second phase of the Haiti-Canada Municipal Cooperation Program (2014-2020) strengthened the achievements of the first phase, notably the management bodies of Les Palmes region in the inter-municipal sharing of resources, the development of development plans and the implementation of local economic development projects. The project successfully supported citizen participation in the management of municipal affairs and tax duty, resulting in a 38% increase in voluntary payment of municipal taxes from 2017 to 2018. The projects in support of decentralized governance demonstrated the potential of grassroots (communal) power building in developing some level of local resilience in an environment where central government capacity was compromised.

Programming across several governance sectors produced appreciable results at some levels of the Haitian state apparatus, but results were mixed and at risk overall.

A UNDP program to which Canada contributed showed preliminary results in providing justice services, including mobilizing state institutions to provide legal international assistance to vulnerable populations, particularly women and children. A project by Lawyers Without Borders Canada (LWBC) also reported positive results in supporting the creation of a collective of lawyers specializing in human rights litigation and support for CSOs providing legal international assistance services.

In the area of economic governance, the Computerization of the Land Registry in Haiti (PIRFH) project was notable for its support to Haiti’s tax authority (Direction générale des Impôts, DGI) and exceeded its objectives in digitalizing the registry and incorporating gender-specific data on land ownership for the first time. The project ensured the operationalization of the registry in 3 important jurisdictions of the country. For the PAMREF project, while some output results were real (improvement of the management system, revision of the customs code, equipment, training, 17.4% increase in customs revenue during the project), results were mixed in terms of sustainability due to withdrawal of a targeted Haitian institution; the end of a contract before completion of the technical installations; and little progress or even a decline in tax pressureFootnote 11.

Several of these structural projects were too short-lived to anchor results, and some had potential for amplification through possible collaborations with other donors, but opportunities were not seized on time by GAC. Despite the inadequate relationship between project duration and expected results, important and relevant results were produced by the PARGEP project, including the creation of the National School of Public Administration (ENAP) in Haiti and the institutional strengthening of certain central government functions. The PATH project, on the other hand, did not achieve its initial objectives of strengthening government structures.

The promising results of some governance projects were seriously questioned as to their sustainability given both the insecurity situation that has strangled the functioning of the country and the erosion of governance at all levels that has blocked the capacity for state accountability.

Results: Agriculture and Environment

Figure 18:

Text version

Figure 18: Picture of an agricultural production in Haiti.

Canada's interventions to improve agriculture spanned several sectors and components with significant results reported.

GAC invested $26.6M in the agricultural sector in response to growing food security needs and the impact of recurring crises on agricultural production. Along with health, this area has long been a cornerstone of Canadian development assistance. Important projects, particularly in Grand-Anse region, varied in nature and type. They included agricultural productivity, support for resilient agriculture and adaptation to climate change, support for market expansion and local access to commodities, training and professional insertion. Mitigating the impacts of climate change and adapting to withstand natural disasters is vital for the country as a whole, where forest cover is rapidly degrading (estimated in 2021 to be between 4.5% to 20%), and where soil erosion threatens food production. According to reports and evaluations, the 23 projects during that period, most of which were implemented by NGOs, helped improve producers' incomes, adapt crops to the risks of disasters, diversify the food supply and increase the economic power of small producers. Training and support for entrepreneurship contributed to better consolidated skills, especially for women farmers. Partners reported that agreements with financial institutions facilitated access to credit and agricultural insurance. For example, the Increasing Food Security and Promoting Public Health project reduced the proportion of households with high food insecurity in its area of intervention from 7% to 4.2% and the proportion of children in acute malnutrition from 3.7% to 1%. The Adaptive and Innovative Solutions to Agri-Food Market Opportunities project produced 565.11 tons of corn from July 2020 to February 2021.

The integration of environmental considerations into overall programming were marginal and limited to the project level.

Projects with significant impact potential were implemented, for example, to develop cleaner energy tools for cookstoves, which have a significant impact on deforestation, and for waste recovery. Projects in the agricultural sector were well aligned with FIAP action areas and targets. However, integration of the environment into GAC's programming was limited to a group of projects, particularly in relation with the development of sustainable agricultural techniques and adaptations.

No structured approach for taking the environment into account on a programmatic scale could be identified. The scope and duration of projects limited the capacity to sustain improvements. Opportunities to consider climate change impact mitigation and disaster adaptation at a more strategic level were missed. Research consistently demonstrates the importance of taking a holistic approach to environmental and climate impact interventions. Considering the interdependence of various factors provides insights into the risks and opportunities that can otherwise be overlooked. Such an approach provides a solid foundation from which to make informed decisions and optimize projects. Several project evaluations pointed to a significant weakness in this area, even in areas of intervention where a better strategy on environmental issues would have been appropriate (Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) and Agriculture Finance and Insurance System in Haiti Project (SYFAAH)).

Results: Humanitarian assistance and post-disaster recovery

Figure 19:

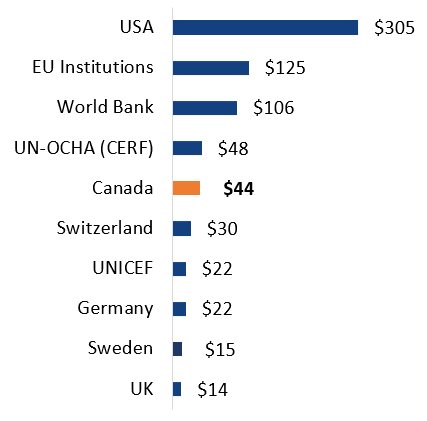

Top donors of humanitarian assistance to Haiti, in millions US, from 2016 to 2021

Text version

Figure 19 :

| Donors of humanitarian assistance | Millions ($US) |

|---|---|

USA | $305 |

EU Institutions | $125 |

World Bank | $106 |

UN – OCHA (CERF) | $48 |

Canada | $44 |

Switzerland | $30 |

UNICEF | $22 |

Germany | $22 |

Sweden | $15 |

UK | $14 |

Source: Aid disbursements (ODA) to countries and regions, OECD.Stat, from 2016 to 2021.

Canada provided a rapid and coherent humanitarian response to the natural disasters that affected Haiti.

Humanitarian assistance accounted for 10.6% of Canada's international assistance to Haiti ($46.23M). The El Niño drought, Hurricane Matthew, the cholera crisis, and the 2018 and 2021 earthquakes all resulted in a Canadian humanitarian response, delivered primarily by multilateral agencies (71.2% of MHD disbursements).