Minister of International Development - Briefing book

2019-11

Table of contents

- A. Global Overview

- B. The Department

- C. First 100 Days

- D. Key Portfolio Responsibilities

- E. Top Issues

- F. Trade Investment Profile

- G. Geographic – Integrated Regional Overview

- H. Multilateral/Global Institutions

- The United Nations

- NATO

- Five Eyes Intelligence Partnership

- Canada and the G7

- Canada and the G20

- World Trade Organization

- International Financial Institutions

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

- Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation

- Inter-American Multilateralism

- La Francophonie

- Commonwealth

- The World Economic Forum

- Association of Southeast Asian Nations

- Canada and the African Union

- I. Glossary

A. Global Overview

Strategic Overview

Issue

- While the last three decades saw dramatic reductions in global poverty, not everyone has benefitted equally.

- Some 736 million people still live in extreme poverty, on less than $1.90/day, and 71 million people have been forcibly displaced by conflict, violence or human rights violations. Women and girls are disproportionally impacted.

- Poverty and inequality, violence and fragility matter for Canadian stability and prosperity. As such, Canada’s Official Development Assistance is an important part of Canada’s wider foreign policy toolkit for managing in a turbulent world.

Context

As Minister of International Development, you will have lead responsibility for delivering Canada’s international development priorities in a department that brings together Canada’s foreign policy, trade and international assistance capabilities in an integrated way to advance Canada’s interests in the world under the rubric of the government’s broader feminist foreign policy. You will be particularly focused on implementing the Feminist International Assistance Policy so that Canada’s international assistance fosters sustainable development and poverty reduction in developing countries. You are also accountable for Canada’s response to humanitarian crises in developing countries.

Canada’s international assistance programming includes initiatives to advance peace, security and governance that requires close collaboration with the Minister of Foreign Affairs. Canada’s aid also complements the work of the Minister of Trade, strengthening and stabilizing the economies of developing countries, creating opportunities for mutually beneficial trading partnerships and advancing Canada’s inclusive trade agenda.

[REDACTED]

To advance your portfolio, you are supported by the Deputy Minister of International Development, and a dedicated network of international assistance experts in Ottawa, and in Canadian embassies around the world.

The International Development Landscape

Your arrival at Global Affairs Canada comes as the international development landscape is shifting, development actors are diversifying, and development challenges are increasingly interconnected. There is an increasing competition of ideas and delivery models.

On the one hand, there are exciting opportunities to harness data, science and technology to support needed social and economic transformations. Moreover, the last three decades have seen unprecedented global development progress, with major gains made to reduce extreme poverty and improve outcomes in areas like health, nutrition, and education. On the other hand, not everyone has benefitted equally. Progress in advancing gender equality has been uneven, and gender and income inequalities persist in every part of the world. Furthermore, a number of other global challenges threaten to seriously roll back development progress, including climate change, protracted conflicts, and natural disasters.

Some 736 million people still live in extreme poverty. Most are in middle income countries. Close to half are children, and the girls among them are especially at risk for exploitation, violence and death (see note on Development Landscape and Challenges). At the same time, poverty is increasingly concentrated in those places least able to provide necessary supports without international help, such as fragile states.

In September 2015, UN member states endorsed the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, a landmark agreement that responds to these challenges. Its 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are intended to help guide international development efforts over a 15-year period. Gender equality is a stand-alone SDG and at the core of Canada’s support for efforts to implement the SDGs globally. Gains in advancing the empowerment of women and girls will contribute to realizing the other SDGs. This is a unique moment to do development differently and to rethink how the world works together to ensure that scarce allocations of resources are aligned and effective to build resilience and leave no one behind.

Traditionally, ODA has been the main tool for international donors like Canada to support poverty reduction and economic growth in developing countries. And while ODA continues to play an essential role for those in greatest need and vulnerable, especially in fragile states or least developed countries, it is not enough on its own, and is being used to help leverage other new sources of development financing that are needed to make gains. This includes working with private sector and philanthropic organizations (i.e. foundations). Private flows, including from remittances, now exceed ODA by a ratio of five-to-one. Beyond these actors, others are also engaging, making the development cooperation landscape increasingly dynamic. Countries such as China, Brazil and India are investing in development elsewhere, bringing their own perspectives to bear, although not all of them align with Canada’s views.

Canada's Contribution to Eradicating Global Poverty and Addressing Humanitarian Crises

Canada has a strong and proud tradition of working internationally to help eradicate global poverty. Canada has been an active and engaged international donor since the 1950s. It has earned a reputation for effective collaboration with developing-country partners in Asia, Africa, Europe, Latin America and the Caribbean.

In June 2017, Canada launched its Feminist International Assistance Policy, which outlines what, how, and where Canada will deliver its aid. The policy seeks to eradicate poverty and build a more peaceful, inclusive, and prosperous world. It emphasizes that promoting gender equality and empowering women and girls is the most effective approach to achieve this goal. Building on Canada’s strong leadership on gender equality since the 1980s, the Policy lays out some ambitious targets. For example, by 2020-21, at least 95 percent of Canada’s bilateral development assistance will either target or integrate gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls. Concretely, this has meant investments in actions that enhance women and girls’ participation in decision-making, advance their human rights and access to resources, and their ability to fully benefit from development. For instance, in 2018-19, Canadas assistance enabled 216,000 women and girls to access justice and public services; and reached more than 408,000 people through projects that help prevent, respond to, and end sexual violence.

In 2018-19, Canada supported womens economic empowerment projects that had a direct impact on 3.5 million people; provided over 2.8 million women and girls with sexual and reproductive health services; and supported some 5,000 civil-society organizations who advocate for human rights and inclusive governance.

Investments in health have been crucial to increasing life expectancy and to reducing infant, child and maternal mortality. Canada has been a global thought-leader and investor in health and nutrition for two decades. Following on two previous global health commitments, in June 2019, Canada committed to increase its funding for womens, childrens and adolescents health and nutrition around the world to $1.4 billion annually by 2023.

Through its international aid, Canada has also made sustained contributions to global efforts to improve education and skills training, including a $400 million commitment to women and girls education in fragile, conflict and crisis situations. Canadas international assistance also supports inclusive governance; promotes peace and security; improves food security; and addresses environmental issues - including aid to vulnerable communities to adapt to, and mitigate, the impacts of climate change. In all of these areas, Canada supports investments, partnerships, innovation and advocacy efforts with the greatest potential to close gender gaps, increase the participation of women in decision-making, and improve everyones chances for success.

Canadas investments have made an impact over the longer-term in countries where we work. For example, through Canadas $3.3 billion in aid to Afghanistan since 2001, significant achievements have been made in education and health. In 2001, there were fewer than 1 million children, mostly boys, enrolled in school; in 2017, there were 8.9 million students enrolled in Afghanistan, including 3.4 million girls and those who have been educated are entering the public service, private sector and Parliament. The under-five mortality rate declined from 137 deaths per 1,000 live births in 2002 to an estimated 70 in 2016.

In addition to its investments in long-term sustainable development, Canada has been a significant contributor to global humanitarian action. Canada currently allocates some $800 million annually for humanitarian action, ranked 6th among donor governments. Canada's humanitarian programming saves lives, maintains human dignity and alleviates suffering resulting from conflict situations, food insecurity and natural disasters in developing countries.

Canada has adopted a gender-responsive approach to humanitarian assistance and in April 2019, launched A Feminist Approach: Gender Equality in Humanitarian Action. In 2018-19, Canadas humanitarian assistance helped to save or improve the lives of over 135 million people in 62 countries, and responded to 22 natural disasters. Canada is also an active advocate diplomatically and a player in international efforts to improve the effectiveness of humanitarian assistance, for example by better meeting the needs of women and girls, and improving the flexibility and predictability of financing.

Canada delivers its international assistance in line with internationally agreed development effectiveness principles and promotes innovative approaches, using evidence and experimentation to find solutions to today’s complex development challenges. In the last several years, a number of new mechanisms have been created, including Canada’s development financing institution, FinDev Canada. During its G7 Presidency, Canada spearheaded the Whistler Principles to Accelerate Innovation for Development Impact.

Canada also works with a range of partners including governments, civil society organizations, international organizations and private sector entities. Your regular engagement with Canadian and international partners will provide opportunities both to shape the international development agenda and advance Canada’s international assistance priorities.

Global Trends

Issue

International relations have entered a period of heightened uncertainty and instability, with established institutions, alliances, and practices being challenged by a shifting balance of power, new economic and social forces, and renewed ideological competition.

Context

An historic shift of geopolitical and economic power from the Atlantic to the Pacific is underway, and as a multi-node world emerges, new and established powers, as well as non-state actors, are seeking to recast the international system to their benefit. Innovations and globalization over the past 25 years helped to bring millions of people out of poverty. But the optimism that accompanied these developments has been tempered more recently by growing inequality, a resurgence of ethno-nationalism, and a return to great power rivalries and proxy warfare.

The consequences of this dynamic evolution impose strategic choices on Canada’s foreign policy.

In promoting its interests abroad, Canada has contributed to developing and strengthening an evolving international system based on rules in which parameters for inter-state behaviour were largely collectively shaped and mutual accountability was expected. In this context, Canada has benefitted from U.S. support and Washington’s position as the world’s leading power, with its vast network of alliances and partners, including NATO and NORAD, which underpin Canada-U.S. security and defence cooperation. [REDACTED] International development and economics have also emerged as domains for geopolitical influence and competition. [REDACTED]

Not surprisingly, these shifting geopolitical realities are straining the existing system of international laws, norms, alliances and institutions. [REDACTED] and in cyberspace, which has become an active domain for geopolitical rivalry and the nefarious activities of non-state actors. [REDACTED]

This shift is increasingly apparent with regards to debt financing. The composition of public debt in Low Income developing Countries (LICs) continues to shift from traditional sources (largely the Paris Club, including Canada) towards non-traditional bilateral lenders [REDACTED] In 2007, 66 percent of public external debt in LICs was held by multilateral development banks or Paris Club members, with just 19 percent held by Non-Paris Club lenders. By 2016 fully 37 percent of public debt in LICs was held by Non-Paris Club, with combined MDB and Paris Club debt down to just 33 percent. Moreover, this presents an incomplete picture of the global debt shift since it only focusses on LICs, and does not account for other forms of financing, including non-governmental foreign direct investment, public funding through non-governmental organizations, or investments through state-owned enterprises with close links to the central government, [REDACTED]

On the security front, several pressures are apparent. Nuclear non-proliferation faces sustained challenges, particularly from Iran, North Korea, [REDACTED] Violent extremism, including in the form of pernicious terrorist groups (e.g. Daesh, Boko Haram, Al-Qaida), white supremacists, and anti-immigrant movements, threaten people around the world. And protracted crises, such as Syria, are extremely costly in terms of lives and livelihoods, and for their regional and international implications.

Change in Creditor Composition of LIDC's Public External Debt 2007 to 2016

Text version

Change in Creditor Composition of LIDCs' Public External Debt

| Creditor Composition | 2007 | 2016 |

|---|---|---|

| Multilateral | 46% | 27% |

| Paris Club | 20% | 6% |

| Plurilateral | 8% | 16% |

| Commercial | 7% | 15% |

| Non-Paris Club | 19% | 37% |

In parallel to these specific preoccupations, globalization continues to reshape economic and social life and has contributed to the shifting balance of power. Freer trade, technological innovation and transnational value chains have raised global standards of living. Between 2000 and 2017, emerging Asian countries (including China and India) increased their share of world GDP from approximately 7 percent to 22 percent and are projected to grow at a much faster rate than advanced economies – [REDACTED] Developing countries are also increasingly urbanized, and some face demographic “youth bulges” in their fast-growing populations – offering the potential for continued growth, especially if jobs can match success in extending life expectancy, but also threatening social stability if they cannot. This speaks to the urgent need to accelerate the achievement of the sustainable development goals.

While increased growth and interconnectedness have created a growing global middle class, the momentum to liberalize international trade has stalled, as evidenced by protracted disagreements over the WTO and rising protectionism. This stems partly from the recognition that the benefits of globalization have been unevenly shared. From 2005 to 2014, 65-70 percent of households in advanced economies, on average, were in income segments whose real market incomes were flat or falling (McKinsey).

International migration, regular and irregular, is expected to increase, with competition for jobs and resources in less-developed regions and labour shortages in developed economies.

Emerging markets, including countries where Canada currently invests significant development assistance, present new economic opportunities, although geopolitical, security and governance-related concerns can limit the scope for engagement in the very near term. These and other complex transnational challenges – including climate change and pandemic diseases – affect Canada directly, and Canada can most effectively protect its prosperity and stability by working alongside new and traditional allies and partners.

Canada faces an international environment of growing great power competition, rising trade protectionism, complex transnational challenges, traditional partners who are distracted or disengaged, and resurgent authoritarianism. Yet amid these challenges are opportunities to shape the evolving international system, embrace new markets and non-traditional partners, regroup with like-minded countries and leverage Canada’s deep people-to-people ties around the world. [REDACTED]

In the context of growing international volatility, Canada’s efforts will require close collaboration between Global Affairs Canada and other government departments and agencies to coordinate a whole-of-government approach. But Canada is equipped with an international policy toolkit to meet many of these challenges: its membership in key institutions such as the UN, G7, G20, NATO, NORAD, APEC, the OECD, the Commonwealth and La Francophonie offers comparative leverage; it sustains a positive global reputation for freedom, tolerance, diversity, gender equality, and good governance, including through our leadership of issue-based alliances; it has trade agreements with all G7 members and has solidified the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) with the EU, as well as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP); and Canada still possesses hard-won, though transient, credibility on issues of peace and security and international development. In this new era of international relations, Canada will need all the tools at its disposal to navigate difficult strategic terrain ahead.

State of the Global Economy / Trade

Issue

- Global growth is softening as geopolitical and trade tensions are disrupting supply chains and have led to a worsening of business sentiment.

- Despite rising concerns of the risk of recession, most projections call for global growth to rebound in 2020, due to stronger performance by emerging markets and developing economies.

- The Canadian economy is expected to grow by 1.5 percent in 2019 and 1.8 in 2020, but weak global trade is expected to moderate business investment and exports.

Context

Global growth is expected to be weak in 2019 in both advanced and emerging economies. Several factors have contributed to this slowdown:

(1) the ongoing trade and technology conflict between the world’s two largest economies (United States and China); (2) Brexit-related uncertainty; (3) rising geopolitical tensions; and (4) business conditions decelerating after years of steady expansion.

Chart 1: Real GDP Growth projections

[REDACTED due to copyright]

The global economy has experienced a long period of growth since the 2008 financial crisis, but this growth is decelerating in 2019. While the global services sector has held up, manufacturing activities have either contracted or decelerated in many major economies in the first half of 2019, as indicated by manufacturing industrial production.

Given the uncertain outlook, it appears that firms and households continue to hold back on long-range spending as shown by weak business spending (machinery and equipment) and consumer purchases of durable goods, such as cars and appliances. The IMF and OECD project global growth to rebound in 2020 due to stronger performances by emerging markets and developing economies, but these projections are for modest growth, and outlooks have been revised downward repeatedly over the last 18 months.

Trade Tensions

[REDACTED]

Global trade growth in volume terms has declined sharply in recent quarters. Escalating trade conflicts and related uncertainty have given rise to concerns about a potential recession, reflecting unease in the global economy.

Uncertain Growth

The U.S. economy is steady for the moment but is sending increasingly mixed signals. Europe is losing momentum as its largest economy, Germany, has contracted in two of the last four quarters. At the same time, China is showing its weakest growth since 1992, a situation that is set to worsen unless the United States and China resolve their trade conflict. There are also concerns about debt sustainability in developing economies, as growing debt burdens, particularly in Latin America and East Asia, have the potential to quickly become unsustainable.

In response to uncertain growth prospects, many central banks, including the United States Federal Reserve, have cut interest rates to provide economic support, but the lower interest rates can also foster financial vulnerabilities as financial markets move to riskier assets. For its part, the Bank of Canada has maintained its rate unchanged since October 2018 (1.75 percent) as core inflation remained around its 2 percent target, but it has flagged that it will continue to watch developments closely.

Regional Update

Canada

In 2018, Canada’s exports of goods and services increased 6.2 percent to $706 billion, while imports rose 5.4 percent. The total value of trade in goods and services reached a record high of $1.5 trillion. However, GDP growth for 2018 as a whole was 1.9 percent, down from three percent in 2017. The slower rate of growth in late 2018 and early 2019 has been attributed to weakness from the goods producing sectors, uncertainties generated by trade tensions between the United States and China and by American tariffs on steel and aluminum (lifted in May 2019). Despite a frail start in 2019 and ongoing weaknesses in the oil-producing sector and corresponding regions, economic growth rebounded to 3.7 percent in Q2 after growing only 0.5 percent in Q1, driven by strong performance in goods exports, although domestic demand was weak. Canada has seen a trade deficit since the global financial crisis. The IMF projects that Canada’s GDP growth will be at 1. 5 percent in 2019 and 1.8 percent in 2020 – both below the 2018 level.

Overall, the Canadian economy remains sound. The strong national labour market, with close to record low unemployment (5.5. percent in September), should bolster household income and support steady growth in household consumption.

Key factors that could affect the short-term outlook are global trade and geo-political tensions, persistent transportation and production constraints in the oil and gas sector, and an elevated level of household indebtedness. Given interconnectedness with the U.S. economy, economic trends in the United States will also impact the Canadian economy.

United States

The current U.S. economic expansion is the longest on record, though talk of a U.S. recession in the next 18 months has risen following the publication of a string of weak leading economic indicators over the summer.

In response, the United States Federal Reserve has cut its interest rate three times this year, the first cuts since the 2008 financial crisis. U.S. GDP is projected by the IMF to continue growing next year but growth is expected to fall from 2.9 percent in 2018 to 2.4 percent in 2019 and 2.1 percent in 2020, as the effects of past fiscal stimulus unwinds and the impacts of tariffs counter measures by other countries make their mark.

Europe

Euro area growth declined to 1.9 percent in 2018 and is projected to further decline to 1.2 percent in 2019, before rebounding to 1.4 percent in 2020. Export-reliant Germany, Europe’s largest economy, has contracted in two of the last four quarters. Growth in the Italian economy has been tepid since the recession that occurred last year, due to business and political uncertainty. In the second quarter of 2019, the U.K. economy contracted for the first time since 2012, as the U.K. ’s stockpiling for Brexit reached a peak and the car industry implemented shutdowns. Going forward, the IMF expects the U.K. economy to grow at 1.2 percent in 2019 and 1.4 percent in 2020. Uncertainties from Brexit continue to weigh on economic prospects in the United Kingdom and the Eurozone.

Emerging and developing Asia

GDP is expected to grow at 5.9 percent in 2019 and 6.0 percent in 2020, lower than previous forecasts, largely reflecting the impact of tariffs on trade and investment. Chinas growth (year over year) dipped to 6 percent in the third quarter of 2019, the lowest on record since 1992. Escalating tariffs have added downward pressure on an economy already in the process of a structural slowdown and regulatory tightening to rein in debt. Chinas slowing growth is expected to spill over to other emerging Asian economies that are integrated in its supply chains. Elsewhere, Indias economy is set to grow at 6.1 percent in 2019, due to weaker-than-expected domestic demand, and by 7 percent in 2020, as fiscal and monetary stimulus start to have an impact. Indias economy has decelerated in the past few quarters, fueling concerns of a structural slowdown. [REDACTED]

Other emerging markets and developing economies

As indicated in Chart 1, economic growth projections are higher for emerging markets and developing economies. For example, the IMF projects that Sub-Saharan Africa as a region will grow at 3.2 percent in 2019 and 3.6 percent in 2020. However, the regionwide numbers mask considerable differences in the growth performance and prospects of their constituent countries. Also, while growth rates can be high, it is often from a smaller base, which means that it will take some time for these countries to play a bigger role in the global economy and global trade.

In the meantime, there are opportunities to leverage Canada`s diplomatic and international assistance relationships to position us for the future, as other countries are already doing.

International Assistance Budget

Issue

- Canada’s international assistance is managed through a dedicated envelope set aside in the fiscal framework. There is $5.75 billion for fiscal year 2019-20.

- [REDACTED]

Context

Most of Canada’s international assistance resources are contained in the International Assistance Envelope (IAE), the Government of Canada’s dedicated pool of resources and main budget planning tool to support international assistance objectives.

[REDACTED]

[REDACTED]

Global Affairs Canada currently manages over 85 percent of the IAE, with the remainder allocated to Finance Canada, the International Development Research Centre, Public Safety, Environment and Climate Change Canada and the Canada Revenue Agency.

Structure

To enhance transparency, Budget 2018 introduced a new pool structure to organize the IAE, and provided the first public projection of the IAE for the 2018-19 fiscal year.

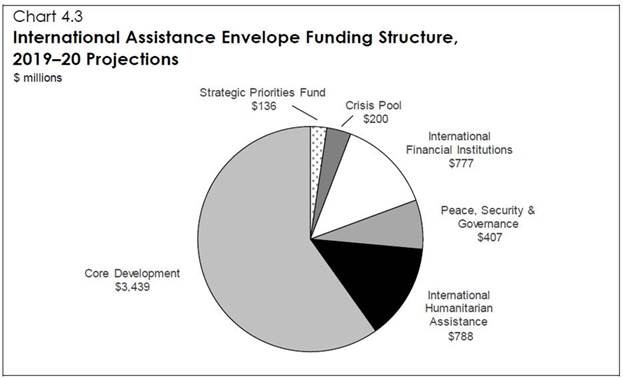

International Assistance Envelope Funding Structure, 2019-20 Projections

Source: © 2019 Department of Finance Canada. Figures include $761 million of funding related to other government departments.

The projected value of each of the six IAE pools (see chart above) is determined at the beginning of the fiscal year and funds are managed in accordance with the Government of Canada’s international assistance policy. The pools represent the range of funding categories available to the Government of Canada to meet its international assistance objectives. Each department is responsible for tracking their own programming across these pools.

[REDACTED].

The vast majority of Canada’s international assistance envelope resources qualify as Official Development Assistance (ODA). The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Development Assistance Committee (OECD-DAC) maintains a list of eligible ODA recipient countries, and in collaboration with member states, establishes the definition of what counts as ODA. Examples of ODA-eligible programming include support for girls’ education, or improving access to maternal and child health care. Some activities funded through the IAE are not eligible to be counted as ODA (ex. most counter-terrorism capacity building).

Beginning in March 2020, reporting on Canada's IAE (including ODA) will for the first time be consolidated in a single report to Parliament. It will be tabled at the same time annually.

Current Commitments and Flexibility

For FY 2019-20, the IAE is $5.75 billion, and has been targeted to meet international pledges and policy commitments. Many of these priorities require multi-year investment decisions. These include multiyear commitments to Global Health, Climate Change, Humanitarian Assistance, IFIs, and Peace and Security (which together will soon occupy nearly [REDACTED] percent of the Department's IAE budget).

The ODA/GNI ratio is currently projected to be [REDACTED] percent in calendar year 2019, which may change based on project disbursements.

Text version

ODA is official support administered with the promotion of the economic and development welfare of developing countries as its main objective.

There are areas of overlap between the IAE and ODA and some programs and/or activities that only fall under one or the other. International assistance comprises programming that is solely IAE-eligible, solely ODA-able and both IAE and ODA-eligible.

IAE only areas include:

- Enforcement aspects of Peace and Security

- Counter-terrorism capacity building

ODA only areas include:

- Debt relief

- Cost of refugees in Canada (1st year)

Examples of ODA elements of the IAE include:

- Humanitarian assistance

- Long-term development assistance

- Approximately 15 % of peacekeeping operations

Examples of current key commitments include:

[REDACTED]

In addition to the financial commitments, Global Affairs Canada is also currently fulfilling public programming targets, including directing 50 percent of bilateral international development assistance to Sub-Saharan Africa and ensuring that 95 percent of bilateral international development assistance investments target or integrate a gender equality perspective/outcome by 2021-2022.

In 2019/2020, there remains some [REDACTED] available in the Crisis Pool in the event of unexpected catastrophic events.

In the short-term, as Minister, you will provide important project-level direction and approvals in support of ongoing targets and commitments for Global Affairs Canada's international assistance resource allocations. For example, you will have discretion to approve specific investments that will go toward meeting Canada's global health commitments. [REDACTED]. You will also have the opportunity to drive global advocacy campaigns in areas of comparative Canadian strength or in greenfield areas should you wish to do so.

A Feminist Approach

On June 9, 2017, Canada launched its Feminist International Assistance Policy. This policy seeks to eradicate poverty and build a more peaceful, inclusive and prosperous world. The policy is premised on the notion that promoting gender equality and empowering women and girls is the most effective approach to achieving this goal. By taking a feminist approach, including in fragile and conflict-affected countries, Canada is supporting initiatives that enhance the protection and promotion of women’s and girl’s rights, their full and equal participation in decision making, and equitable access to resources.

Future Commitments and Flexibility

[REDACTED]. Taking into account existing commitments and priorities, each year the department develops comprehensive investment plans for the allocation of available resources for geographic programs, Canadian partners, multilateral and other international partners, humanitarian assistance, and peace and security programing. These allocations usually take place on a multi-year basis given the long-term nature of most international assistance programming.

[REDACTED]

Investment-level decision-making takes place throughout the year, in accordance with the delegation instrument, with input from investment review committees.

Periodic financial briefings will provide an overview of amounts currently committed and those remaining available against future commitments.

International Horizon Issues (November 2019 - March 2020)

North America

Relations with U.S.:

- CUSMA ratification (timelines TBD)

- [REDACTED]

- [REDACTED]

- [REDACTED]

- [REDACTED]

- [REDACTED]

Mexico:

- [REDACTED]

- Central American migration

Europe

Regional:

- [REDACTED] Middle East and African migration

- Developments [REDACTED]

EU/United Kingdom:

- Brexit negotiations (new bilateral trade agreement)

- CETA ratification by all EU member states

- Follow-up from 17th Canada-EU Summit (June 2019)

Ukraine:

- Military training mission (Op UNIFIER) and other security cooperation

- Ongoing political reforms

Russia:

- Crimea and Eastern Ukraine

- [REDACTED]

- [REDACTED]

- Intermediate-range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty

- [REDACTED]

- [REDACTED]

Romania:

- [REDACTED]

Latin America and the Caribbean

- Migration flows and impact [REDACTED]

- Venezuela: ongoing political crisis, LIMA group engagement/leadership

- Caribbean: managing hurricane season

- Latin America: [REDACTED]

Africa

- African Continental Free Trade Agreement and growth opportunities

- Political transitions [REDACTED]

- Security situation [REDACTED]

- Sahel: mitigate terrorism, [REDACTED] G7 and broader coordination of international efforts

- Piracy in the Gulf of Guinea and migration to Europe

Global themes/trends to watch

- [REDACTED]

- [REDACTED]

- [REDACTED]

- Democratic institutions, processes, and freedoms under threat

- [REDACTED] and violent extremism

- Peace, stability and climate change

- Scale and drivers of migration

- Diverging approaches to cyberspace, online platforms, new digital technologies and regulations

Multilateral

G7/G20:

- Signature initiatives from Canada's 2018 G7 Presidency – implementation & follow-up

- G7 transition from France to U.S.

- G20 transition from Japan to Saudi Arabia

UN:

- Canada's UN Security Council campaign (vote in June 2020), related events/interactions

- Secretary General Guterres' vision for UN Reform

- Implementation of Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development (Decade of Action 2020-2030)

- UN Framework Convention on Climate Change – (COP25, December 2019)

WTO:

- Appellate Body appointment stalemate (December 10 deadline)

- WTO reform initiatives (Ottawa Group: transparency, dispute settlement, rule-making)

- [REDACTED]

NATO:

- Foreign Ministers' Meeting (Nov. 2019) and Leaders Summit (Dec. 2019)

- [REDACTED]

- Contributions to NATO missions in Iraq and Latvia

- [REDACTED]

Plurilateral trade agreements:

- CPTPP (Canada ratified Dec 2018)

- [REDACTED]

- [REDACTED]

Treaty on the Non-proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT):

- 2020 Review Conference

Global Replenishments:

- Global Fund (October 2019)

- Green Climate Fund (October 2019)

International Development:

- Nairobi Summit (Nov 2019): 25th anniversary of Int'l Conference on Population and Development

- "Beijing 25+" (March 2020, New York): 25th anniversary of Fourth World Conference on Women

Legal/Regulatory

- [REDACTED]

- [REDACTED]

- [REDACTED]

High profile consular cases

- [REDACTED]

- [REDACTED]

- [REDACTED]

- [REDACTED]

Middle East

Turkey/Syria:

- [REDACTED]

- White Helmets (civilian volunteer group), government as gatekeeper of aid operations

Regional:

- Instability in the Strait of Hormuz

- Regional spillover [REDACTED]

- Global Coalition against Daesh

- Political transitions [REDACTED]

Israel/ Middle East Peace Process (MEPP):

- [REDACTED]

- [REDACTED]

- [REDACTED]

Gulf States:

- Bilateral relations with [REDACTED]

- [REDACTED] humanitarian situation, peace talks

- Human rights concerns [REDACTED]

- [REDACTED]

Iran:

- [REDACTED]

Libya:

- Escalating civil conflict, political and institutional backsliding

Asia

Regional:

- [REDACTED]

- [REDACTED]

China:

- [REDACTED]

- [REDACTED]

- [REDACTED]

- [REDACTED]

- [REDACTED]

- [REDACTED]

Northeast Asia:

- [REDACTED]

North Korea:

- Nuclear negotiations [REDACTED]

- Multilateral efforts [REDACTED]

- Human rights and humanitarian situation

South Asia:

- Situation [REDACTED]

- [REDACTED]

Afghanistan:

- [REDACTED]

- Peace process

Myanmar:

- Rohingya crisis [REDACTED]

- Reinforce democratic transition

B. The Department

The Department at a Glance

Issue

Global Affairs Canada is responsible for shaping and advancing Canada’s integrated foreign policy, international trade and international assistance objectives, and supporting Canadian consular and business interests. We have 10,707 employees working in Canada and in 178 missions in 110 countries around the world with a total budget of $6.7 billion.

Who We Are

Canada’s first foreign ministry was established in June 1909. Since then, the department has progressively transformed itself to reflect the changing international environment. The most significant transformations include its amalgamation with the Department of Trade and Commerce in 1982 and with the Canadian International Development Agency in 2013.

While the legal name of the department (pursuant to the Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Act of June 26, 2013) remains the Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development, its public designation under the Federal Identity Program is Global Affairs Canada.

What We Do

Global Affairs Canada manages Canada’s diplomatic and consular relations with foreign governments and international organizations, engaging and influencing international players to advance Canada’s security and prosperity in a dynamic global context.

The department develops and implements Canada’s political, trade and international assistance policy and programming priorities based on astute analysis, consultation and engagement with other government departments, Canadians and international stakeholders.

The department’s work is focused on five core responsibilities:

1) International Advocacy and Diplomacy:

Promote Canada’s interests and values through policy development, diplomacy, advocacy, and engagement with diverse stakeholders. This includes building and maintaining constructive relationships to Canada’s advantage, primarily through our network of missions; taking leadership on select global issues; and efforts to build strong international institutions and respect for international law.

2) Trade and Investment:

Support increased trade and investment to raise the standard of living for all Canadians. This includes building and safeguarding an open and inclusive rules-based global trading system; support for Canadian exporters and innovators in their international business development efforts; negotiation of bilateral, plurilateral and multilateral trade agreements; administration of export and import controls; management of international trade disputes; facilitation and expansion of foreign direct investment; and support to international innovation, science and technology.

3) Development, Humanitarian Assistance, Peace and Security Programming:

Contribute to reducing poverty and increasing opportunity for people around the world. This includes alleviating suffering in humanitarian crises; reinforcing opportunities for sustainable and equitable economic growth; promoting gender equality and women’s empowerment; improving health and education outcomes; and bolstering peace and security through programs that counter violent extremism and terrorism, support anti-crime capacity building, peace operations and conflict management.

4) Help for Canadians Abroad:

Provide timely and appropriate travel information and consular services for Canadians abroad, contributing to their safety and security. This includes visits to places of detention; deployment of staff to evacuate Canadians in crisis situations; and provision of emergency documentation.

5) Support for Canada's Presence Abroad:

Deliver resources, infrastructure and services to enable Canada’s whole-of-government presence abroad. This includes the management of our missions abroad and the implementation of a major Duty of Care initiative to ensure the protection of Government of Canada personnel, overseas infrastructure and information.

Legal Responsibilities

The Department is the principal source of advice on public international law for the Government of Canada, including international trade and investment law. Global Affairs Canada lawyers develop and manage policy and advice on international legal issues, provide for the interpretation and analysis of international agreements, and advocate on behalf of Canada in international negotiations and litigation. There are also a number of Department of Justice lawyers at the Department, who provide legal services under domestic law, including on litigation and regulations such as sanctions implementation.

Our Workforce

To deliver on its mandate, the Department relies on a workforce that is flexible, competent, diverse and mobile.

The department counts 10,707 active employees. The majority of them (6,875 – 64 percent) are Canada-Based Staff (CBS), serving either in Canada or at our missions abroad. The remaining 3,832 employees (36 percent of our workforce) are Locally Engaged Staff (LES), usually foreign citizens hired in their own countries to provide support services at our missions. Currently, 56 percent of Canada-based staff are women (compared to 54 percent of LES) and 60 percent have English as their first official language (40 percent French).

A distinctive human resources system allows the Department to meet its complex operational needs in a timely manner. Our staff work in some of the most difficult places on earth, including in active conflict zones. Among the various occupational groups and assignment types, a cadre of rotational employees supports delivery of the Department’s unique mandate through assignments typically ranging between two to four-year periods, alternating between missions abroad and headquarters. They are foreign service officers (in trade, political, economic, international assistance, and management and consular officer streams), administrative assistants, computer systems specialists and executives, including our Heads of Mission.

Heads of Mission serve the Minister further to a cabinet appointment. They develop deep expert knowledge of their countries of accreditation, establish wide networks, and provide advice and guidance on pressing matters of bilateral and international concern. The Head of Mission is responsible for Canada’s “whole of government” engagement in their countries of accreditation and for the supervision of all federal programs present in their mission.

Global Affairs Canada personnel work in Canada and abroad to advance Canadian interests through creative diplomacy ranging from formal negotiations and network building to stakeholder engagement and capacity building. Canadian officials take part in thousands of international meetings every year on a multitude of topics, advancing Canadian interests through formal and informal interactions with representatives from virtually every country on earth. These efforts are aligned carefully with the priorities of the department and are amplified through targeted public diplomacy, including on social media.

The department is also supported by a 24/7 Emergency Watch and Response Centre in Ottawa which is always on guard to assist Canadians in need of consular assistance abroad or to respond in real time to natural disasters and complex emergencies around the globe.

Our finances

The Departments total funding in the 2019-20 Main Estimates was $6.7 billion. This amount is broken down as follows:

- Vote 1 (Operating): $1,743.4 million

- Vote 5 (Capital): $103.1 million

- Vote 10 (Grants and Contributions): $4,192 million

- Vote 15 (LES pension, insurance, social security programs): $68.9 million

- Budget Implementation : $269.5 million

- Statutory items (e.g. direct payments to international financial institutions; contributions to employee benefit plans): $342. 8 million.

The budget distribution by core responsibility of the Department in the 2019-20 Main Estimates was reported as follows:

2019-20 Core Responsibilities and Planned Spending (in millions)

Text version

2019-20 Core Responsibilities and Planned Spending (in millions)

| Core Responsibilities | Planned Spending |

|---|---|

| International Advocacy and Diplomacy | 873.6 |

| Trade and Investment | 327.1 |

| Development, Peace and Security Programming | 3920.9 |

| Help for Canadians Abroad | 51.0 |

| Support for Canada's Presence Abroad | 1031.8 |

| Internal Services | 245.6 |

Our network

The departments extensive network abroad counts 178 missions in 110 countries (see attached placemat for an overview of the network). They range in type and status from large embassies, to small representative offices and consulates.

The departments network of missions abroad also supports the international work of 37 Canadian partner departments, agencies and co-locators (such as Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada; National Defence; Canada Border Services Agency; Public Safety; Royal Canadian Mounted Police; Export Development Canada; several provinces).

The departments headquarters offices are located in the Ottawa-Gatineau region. Most staff are located in the first three buildings:

- Lester B. Pearson Building (125 Sussex)

- John G. Diefenbaker Building(111 Sussex)

- Place du Centre (200 Promenade du Portage)

- Queensway Corporate Campus (4200 Labelle)

- Cooperative House (295 Bank)

- National Printing Bureau(45 Sacré-Coeur)

- Fontaine Building (200 Sacré-Coeur)

- Bisson Centre (the Canadian Foreign Service Institute Bisson Campus)

The department also has six Canadian regional offices to engage directly with Canadians, notably Canadian businesses:

- Vancouver

- Calgary

- Winnipeg

- Toronto

- Montréal

- Halifax

Senior leadership and corporate governance

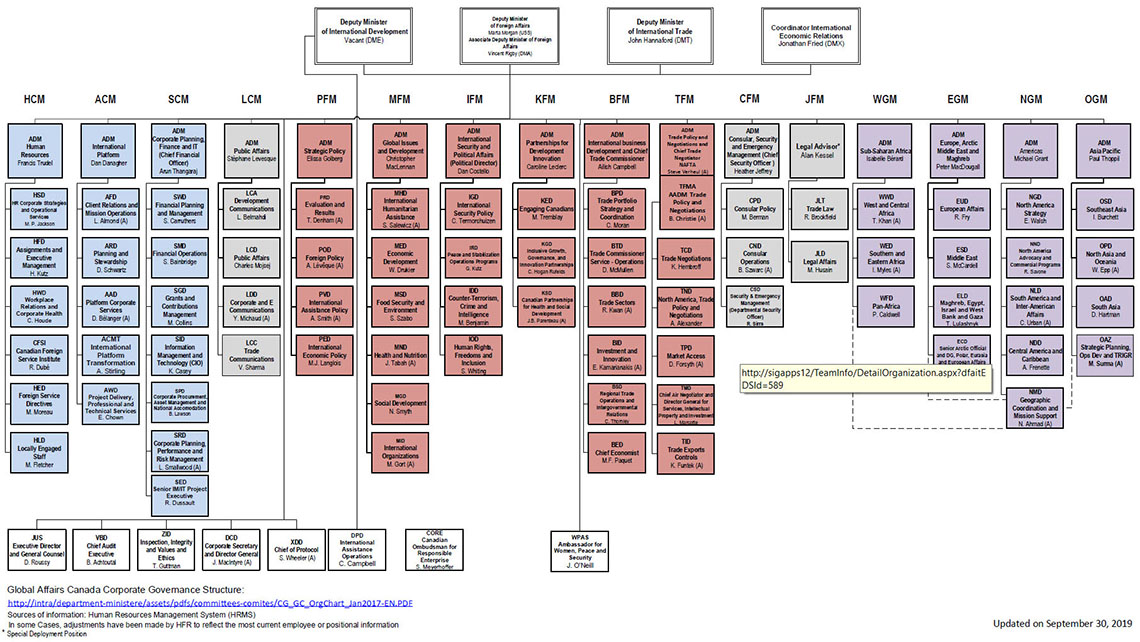

In support of Ministers, the department’s most senior officials are the Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs (USS); the Deputy Minister of International Trade (DMT); the Deputy Minister of International Development (DME); the Associate Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs (DMA); and the Coordinator for International Economic Relations (DMX). Sixteen Branches, headed by Assistant Deputy Ministers, report to the Deputy Ministers and are responsible for providing integrated advice across various portfolios, ranging from geographic regions to corporate and thematic issues. (See separate bios)

Canada’s Heads of mission abroad are responsible for the management and direction of mission activities, and the supervision of the official activities of the various departments and agencies of the Government of Canada in the country or at the international organization to which they are appointed.

The department has a robust corporate governance framework with specific committees for audit, evaluation, resource and corporate management, policy and programs.

Senior managers from headquarters and the mission network manage and integrate the department’s policies and resources in this context to maximize our assets, and ensure accountability for the delivery of departmental programs and results. The amalgamated approach in the Department results in more coherent and cohesive international engagement, supported by an integrated organizational structure.

2019-2020 Corporate Governance Committee Structure

Text version

Chart summarizing 2019-2020 Corporate governance structure

- External Committee: Departmental Audit Committee

- DM-chaired committees: Executive Committee and Performance Measurement and Evaluations Committee

- ADM-chaired Committees: Security Committee; Financial Operations and Management Committee; Corporate Management Committee; and Policy and Programs Committee. All four ADM-chaired committees report to the Executive Committee.

Planning and reporting

The department’s annual planning and reporting process is structured around its Departmental Results Framework.

A Departmental Plan establishes the Government’s foreign affairs, international trade and development agenda for the coming year. It provides a strategic overview of the policy priorities, planned results and associated resource requirements for the coming fiscal year. The document is approved by the Ministers and tabled in Parliament (usually in March-April). The Plan also presents the performance targets against which the department will report its final results at the end of the fiscal year through a Departmental Results Report, typically tabled in Parliament in late fall.

A Corporate Plan acts as a companion piece, and is the Department's operational plan, aligning the work of branches and missions with the strategic plans and priorities established by the Departmental Plan and financial and human resources. The Corporate Plan ensures the integration of key enabling functions, such as human resources, IM/IT, communications, business continuity and risk management, into one operational planning process. The Corporate Plan is finalized in time for the start of each fiscal year in April.

Annex

Global Affairs Canada Network Placemat

Global Affairs Canada Organizational Chart

Biographies of senior officials

Deputy Ministers

Marta Morgan, Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs

On April 18, 2019, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau appointed Marta Morgan to the position of Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs, effective May 6, 2019.

Prior to joining Global Affairs Canada, since June 2016, Ms. Morgan was deputy minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada. In that previous role, she led the development of immigration policies and programs to support Canada’s economic growth, developed strategies to manage the significant growth in asylum claims and improved client service.

Before that, Ms. Morgan acquired extensive leadership experience in a range of economic policy roles both at Industry Canada and the Department of Finance Canada. In those departments, as assistant deputy minister and associate deputy minister, she provided leadership in telecommunications policy, spectrum policy, aerospace and automobile sectoral policy, and in the development of two federal budgets.

Prior to her time at Industry Canada, Ms. Morgan held positions at the Forest Products Association of Canada, the Privy Council Office, and Human Resources Development Canada.

She has also been a member of the board of the Public Policy Forum since 2014.

Ms. Morgan has a Bachelor of Arts (Honours) in economics from McGill University and a Master in Public Policy from the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University.

John Hannaford, Deputy Minister of International Trade

On December 7, 2018, the Prime Minister appointed John Hannaford Deputy Minister of International Trade at Global Affairs Canada, effective January 7, 2019.

From January 2015 to January 2019, Mr. Hannaford was the foreign and defence policy adviser to the Prime Minister and Deputy Minister in the Privy Council Office of the Government of Canada. Until December 2014, Mr. Hannaford was the assistant secretary to the Cabinet for foreign and defence policy in the Privy Council Office. Prior to December 2011,

Mr. Hannaford was Canada’s ambassador to Norway. Before that, for two years, Mr. Hannaford was director general of the Legal Bureau of the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade. As a member of Canada’s foreign service, he had numerous assignments in Ottawa and at the Canadian embassy in Washington, D. C. , during the early years of his career.

Mr. Hannaford graduated from Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario, with a Bachelor of Arts in history. After earning a Master of Science in international relations at the London School of Economics, he completed a Bachelor of Laws at the University of Toronto and was called to the bar in Ontario in 1995.

In addition to his work as a public servant, Mr. Hannaford has been an adjunct professor in both the Faculty of Law and the Graduate School of Public and International Affairs at the University of Ottawa.

Vincent Rigby, Associate Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs

On July 31, 2019, the Prime Minister appointed Vincent Rigby as Associate Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs at Global Affairs Canada, effective August 12, 2019.

Prior to this appointment, Mr. Rigby was Associate Deputy Minister of Public Safety Canada from July 2017 until August 2019.

From 2013 to 2017, Mr. Rigby was Assistant Deputy Minister of Strategic Policy at Global Affairs Canada, where he was responsible for providing integrated strategic policy advice reflecting the foreign policy, international assistance and international trade streams of the Department. In this capacity, Mr. Rigby also served as the Personal Representative (Sherpa) to the Prime Minister on the G20, supporting three G20 Leaders’ Summits. Mr. Rigby carried out a number of additional roles as Assistant Deputy Minister, including as the Department’s Chief Results and Delivery Officer, G7 Sous-Sherpa, Chief Negotiator for the Post-2015 Development Agenda, and Chair of the Arctic Council’s Senior Arctic Officials.

Before the creation of Global Affairs Canada, Mr. Rigby was Vice-President of the Strategic Policy and Performance Branch of the former Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA). In this role, Mr. Rigby was responsible for developing and coordinating Canada’s international assistance policy as well as overseeing the performance management and evaluation of Canada’s development programme.

From 2008 to 2010, Mr. Rigby was the Executive Director of the International Assessment Secretariat (IAS) at the Privy Council Office (PCO). Mr. Rigby was also Afghanistan Intelligence Lead Official while at PCO, responsible for coordinating the Canadian intelligence community in support of Canada’s Afghanistan mission.

Before arriving at PCO, Mr. Rigby was Assistant Deputy Minister (Policy) at the Department of National Defence (DND) from 2006 to 2008. Over his 14 years at DND, Mr. Rigby held a number of other positions within the Policy Group, including Director General Policy Planning, Director of Policy Development and Director of Arms and Proliferation Control Policy. Prior to joining DND, he was a defence and foreign policy analyst at the Research Branch of the Library of Parliament, from 1991 to 1994.

Mr. Rigby holds an MA in diplomatic and military history from Carleton University in Ottawa.

Jonathan T. Fried, Coordinator, International Economic Relations

Mr. Fried is the Personal Representative of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau for the G20 and Coordinator for International Economic Relations at Global Affairs Canada, with a horizontal mandate to ensure coherent policy positions and government-wide strategic planning in international economic organizations and forums regarding, for example, Canada-Asia and other international trade and economic issues.

He served as Canada’s Ambassador and Permanent Representative to the WTO from 2012 to 2017, where he played a key role in multilateral trade negotiations, including as Chair of the WTO’s General Council in 2014 and chair of the Dispute Settlement Body in 2013. He was the co-Chair of the G20’s Trade and Investment Working Group with China in 2015, and the “Friend of the Chair” for Germany in 2016. Formerly Canada’s Ambassador to Japan; Executive Director for Canada, Ireland and the Caribbean at the International Monetary Fund; Senior Foreign Policy Advisor to the Prime Minister; Senior Assistant Deputy Minister for the Department of Finance and Canada's G7 and G20 Finance Deputy. Mr. Fried has also served as Associate Deputy Minister; Assistant Deputy Minister for Trade, Economic and Environmental Policy; Chief Negotiator on China’s WTO accession; Director General for Trade Policy; and chief counsel for NAFTA.

Mr. Fried is a member of the World Economic Forum’s Global Agenda Council on Trade and Investment and of the Steering Committee of the e15 initiative on Strengthening the Global Trading System. He serves on the advisory boards of the Columbia Center on Sustainable Investment, the World Trade Symposium and the Central and East European Law Institute. Mr. Fried was named in 2015 as the inaugural recipient of the Public Sector Lawyer Award by the Canadian Council on International Law to honour his service and contribution to public international law.

Global Affairs Canada Executive (EX) Organizational Structure

Text version

Level 1 – Deputy Ministers and Coordinator

Deputy Minister of International Development – Vacant (DME)

Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs – Marta Morgan (USS)

Associate Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs – Vincent Rigby (DMA)

Deputy Minister of International Trade – John Hannaford (DMT)

Coordinator International Economic Relations – Jonathan Fried (DMX)

Level 2 – Assistant Deputy Ministers and Directors General

Reports to the Deputy Minister of International Development

International Assistance Operations – C. Campbell

Reports to all Deputy Ministers and Coordinator

Assistant Deputy Minister Human Resources – Francis Trudel (HCM)

Assistant Deputy Minister International Platform – Dan Danagher (ACM)

Assistant Deputy Minister Corporate Planning, Finance and IT (Chief Financial Officer) – Arun Thangaraj (SCM)

Assistant Deputy Minister Public Affairs – Stéphane Levesque (LCM)

Assistant Deputy Minister Strategic Policy – Elissa Golberg (PFM)

Assistant Deputy Minister Global Issues and Development – Christopher MacLennan (MFM)

Assistant Deputy Minister International Security and Political Affairs (Political Director) – Dan Costello (IFM)

Assistant Deputy Minister Partnership for Development Innovation – Caroline Leclerc (KFM)

Assistant Deputy Minister International Business Development and Chief Trade Commissioner – Ailish Campbell (BFM)

Assistant Deputy Minister Trade Policy and Negotiations and Chief Trade Negotiator NAFTA – Steve Verheul (A) (TFM)

Assistant Deputy Minister Consular, Security and Emergency Management (Chief Security Officer) – Heather Jeffrey (CFM)

Legal Adviser – Alan Kessel (JFM) – Special Deployment Position

Assistant Deputy Minister Sub-Saharan Africa – Isabelle Bérard (WGM)

Assistant Deputy Minister Europe, Arctic, Middle East and Maghreb – Peter MacDougall (EGM)

Assistant Deputy Minister Americas – Michael Grant (NGM)

Assistant Deputy Minister Asia Pacific – Paul Thoppil (OGM)

Executive Director and General Counsel – D. Roussy (JUS)

Chief Audit Executive – B. Achtoutal (VBD)

Director General, Inspection, Integrity and Values and Ethics – T. Guttman (ZID)

Corporate Secretary and Director General – J. MacIntyre (A) (DCD)

Chief of Protocol – S. Wheeler (A) (XDD)

Ambassador for Women, Peace and Security – Jacqueline O’Neil (WPSA)

Level 3 – Directors General

Reports to the Assistant Deputy Minister Human Resources

HR Corporate Strategies and Operational Services – M. P. Jackson (HSD)

Assignments and Executive Management – H. Kutz (HFD)

Workplace Relations and Corporate Healthcare – C. Houde (HWD)

Canadian Foreign Service Institute – R. Dubé (CFSI)

Foreign Service Directives – M. Moreau (HED)

Locally Engaged Staff – M. Fletcher (HLD)

Reports to the Assistant Deputy Minister International Platform

Client Relations and Mission Operations – L. Almond (AFD)

Planning and Stewardship – D. Schwartz (ARD)

Platform Corporate Services – D. Bélanger (A) (AAD)

International Platform Transformation – A. Stirling (ACTM)

Project Delivery, Professional and Technical Services – E. Chown (AWD)

Reports to the Assistant Deputy Minister Corporate Planning, Finance and IT (Chief Financial Officer)

Financial Planning and Management – S. Carruthers (SWD)

Financial Operations – S. Bainbridge (SMD)

Grants and Contributions Management – M. Colins (SGD)

Information Management and Technology (CIO) – K. Casey (SID)

Director General, Corporate Procurement, Asset Management and National Accommodation – B. Lawson (SPD)

Corporate Planning, Performance and Risk Management – L. Smallwood (A) (SRD)

Senior IM/IT Project Executive – R. Dussault (SED)

Reports to the Assistant Deputy Minister Public Affairs

Development Communications – L. Belmahdi (LCA)

Public Affairs – Charles Mojsej (LCD)

Corporate and E Communications – Y. Michad (A) (LDD)

Trade Communications – V. Sharma (LCC)

Reports to the Assistant Deputy Minister Strategic Policy

Evaluation and Results – T. Denham (A) PRD)

Foreign Policy – A. Lévêque (A) (POD)

International Assistance Policy – A. Smith (A) (PVD)

International Economic Policy – M.J. Langlois (PED)

Reports to the Assistant Deputy Minister Global Issues and Development

International Humanitarian Assistance – S. Salewicz (A) (MHD)

Economic Development – W. Drukier (MED)

Food Security and Environment – S. Szabo (MSD)

Health and Nutrition – J. Tabah (A) (MND)

Social Development – N. Smyth (MGD)

International Organizations – M. Gort (A) (MID)

Reports to the Assistant Deputy Minister International Security and Political Affairs (Political Director)

International Security Policy – C. Termorshuizen (IGD)

Peace and Stabilization Operations Program – G. Kutz (IRD)

Counter-Terrorism, Crime and Intelligence – M. Benjamin (IDD)

Human Rights, Freedom and Inclusion – S. Whiting (IOD)

Reports to the Assistant Deputy Minister Partnership for Development Innovation

Engaging Canadians – M. Tremblay (KED)

Inclusive Growth, Governance and Innovation Partnerships – C. Hogan Rufelds (KGD)

Canadian Partnership for Health and Social Development – J.B. Parenteau (A) (KSD)

Reports to the Assistant Deputy Minister International Business Development and Chief Trade Commissioner

Trade Portfolio Strategy and Coordination – C. Moran (BPD)

Trade Commissioner Service - Operations – D. McMullen (BTD)

Trade Sectors – R. Kwan (A) (BBD)

Investment and Innovation – E. Kamarianakis (A) (BID)

Regional Trade Operations and Intergovernmental Relations – C. Thomley (BSD)

Chief Economist – M.F. Paquet (BED)

Reports to the Assistant Deputy Minister Trade Policy and Negotiations and Chief Trade Negotiator

Associate Assistant Deputy Minister, Trade Policy and Negotiations – B. Christie (A) (TFMA)

Reports to the Associate Assistant Deputy Minister, Trade Policy and Negotiations

Trade Negotiations – K. Hembroff (TCD)

North America, Trade Policy and Negotiations – A. Alexander (TND)

Market Access – D. Forsyth (A) (TPD)

Chief Air Negotiator and Director General for Services, Intellectual Property and Investment – L. Marcotte (TMD-ANA)

Trade and Exports Control – K. Funtek (A) (TID)

Reports to the Assistant Deputy Minister Consular, Security and Emergency Management

Consular Policy – M. Berman (CPD)

Consular Operations – B. Szwarc (A) CND)

Security and Emergency Management (Departmental Security Officer) – R. Sirrs (CSD)

Reports to the Legal Adviser

Trade Law – R. Brookfield (JLT)

Legal Affairs – M. Husain (JLD)

Reports to the Assistant Deputy Minister Sub-Saharan Africa

West and Central Africa – T. Khan (A) (WWD)

Southern and Eastern Africa – I. Myles (A) (WED)

Pan-Africa – P. Caldwell (WFD)

Reports to the Assistant Deputy Minister Europe, Arctic, Middle East and Maghreb

European Affairs – R. Fry (EUD)

Middle East - S. McCardell (ESD)

Maghreb, Egypt, Israel and West Bank and Gaza – T. Lulashnyk (ELD)

Senior Arctic Official and Director General, Polar, Eurasia and European Affairs - D. Sproule (A) (ECD)

Reports to the Assistant Deputy Minister Americas

North America Strategy – E. Walsh (NGD)

North America Advocacy and Commercial Programs – R. Savone (NND)

South America and Inter-American Affairs – C. Urban (A) (NLD)

Central America and Caribbean – A. Frenette (NDD)

Geographic Coordination and Mission Support – N. Ahmad (A) (NMD)

Reports to the Assistant Deputy Minister Asia Pacific

Southeast Asia – Ian Burchett (OSD)

North Asia and Oceania – W. Epp (A) (OPD)

South Asia – D. Hartman (OAD)

Strategic Planning, Ops Dev and TRIGR – M. Suma (A) (OAZ)

Level 4 – Outside of Main Organizational Structure

Canadian Ombudsperson for Responsible Enterprise – Sheri Meyerhoffer (CORE)

Source of information: Human resources Management System (HRMS)

In some cases, adjustments have been made by HFR to reflect the most current employee or positional information.

Link to Global Affairs Canada Corporate Governance Structure (http://intra/department-ministere/assets/pdfs/committees-comites/CG_GC_OrgChart_Jan2017-EN.PDF).

Updated on September 30, 2019

Mission Network

Text version

Summary of Missions / Points of Service

| Designation | Category 1 | Category 2 | Category 3 | Category 4 | Category 5 | Total by Category |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Embassies | 9 | 49 | 18 | 2 | 0 | 78 |

| High Commissions | 2 | 12 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 22 |

| Embassy/High Commission of Canada (Program) Offices | 0 | 0 | 1 | 10 | 0 | 11 |

| Offices of the Embassy / High Commission | 0 | 0 | 1 | 11 | 1 | 13 |

| Representative Offices | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Multilaterals or Permanent | 5 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 11 |

| Consulates General | 1 | 15 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 25 |

| Consulates | 0 | 0 | 3 | 7 | 0 | 10 |

| Consular Agencies | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| Regional Offices | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 17 | 81 | 33 | 46 | 1 | 178 |

| Designation | Europe & Middle East | Asia Pacific | Africa | Americas | Canada | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Embassies | 42 | 10 | 9 | 17 | 0 | 78 |

| High Commissions | 1 | 9 | 8 | 4 | 0 | 22 |

| Embassy/High Commission of Canada (Program) Offices | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 11 |

| Offices of the Embassy / High Commission | 2 | 6 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 13 |

| Representative Offices | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Multilaterals or Permanent | 8 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 11 |

| Consulates General | 2 | 9 | 0 | 15 | 0 | 26 |

| Consulates | 2 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 9 |

| Consular Agencies | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| Australian, CCC & Other Offices | 0 | 26 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 26 |

| Regional Offices in Canada | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 5 |

| Honorary Consulates | 37 | 15 | 17 | 32 | 0 | 101 |

| Total by Geographic Portfolio | 98 | 82 | 38 | 87 | 5 | 310 |

Points of Service excluding Australian, CCC & Other Offices, Regional Offices and Honorary Consulates: 178

Europe & Middle East

Embassies (E)

| Mission | Country | Designation / Title | Category |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abu Dhabi | United Arab Emirates | The Embassy of Canada to the United Arab Emirates | 2 |

| Algiers | Algeria | The Embassy of Canada to Algeria | 2 |

| Amman | Jordan | The Embassy of Canada to Jordan | 2 |

| Ankara | Turkey | The Embassy of Canada to Turkey | 2 |

| Astana | Kazakhstan | The Embassy of Canada to Kazakhstan | 3 |

| Athens | Greece | The Embassy of Canada to Greece | 2 |

| Baghdad | Iraq | The Embassy of Canada to Iraq | 3 |

| Beirut | Lebanon | The Embassy of Canada to Lebanon | 2 |

| Belgrade | Republic of Serbia | The Embassy of Canada to the Republic of Serbia | 2 |

| Berlin | Germany | The Embassy of Canada to Germany | 1 |

| Berne | Switzerland | The Embassy of Canada to Switzerland | 2 |

| Brussels | Belgium | The Embassy of Canada to Belgium | 2 |

| Bucharest | Romania | The Embassy of Canada to Romania | 2 |

| Budapest | Hungary | The Embassy of Canada to Hungary | 2 |

| Cairo | Egypt | The Embassy of Canada to Egypt | 2 |

| Copenhagen | Denmark | The Embassy of Canada, Copenhagen, Denmark | 2 |

| Damascus | Syria | The Embassy of Canada to Syria | 2 |

| Doha | Qatar | The Embassy of Canada to Qatar | 3 |

| Dublin | Ireland | The Embassy of Canada, Dublin, Ireland | 2 |

| Hague, The | Netherlands | The Embassy of Canada to the Netherlands | 2 |

| Helsinki | Finland | The Embassy of Canada to Finland | 2 |

| Kuwait City | Kuwait | The Embassy of Canada to Kuwait | 2 |

| Kyiv | Ukraine | The Embassy of Canada to Ukraine | 2 |

| Lisbon | Portugal | The Embassy of Canada to Portugal | 2 |

| Madrid | Spain | The Embassy of Canada to Spain | 2 |

| Moscow | Russian Federation | The Embassy of Canada to Russia | 1 |

| Oslo | Norway | The Embassy of Canada to Norway | 2 |

| Paris | France | The Embassy of Canada to France | 1 |

| Prague | Czech Republic | The Embassy of Canada to the Czech Republic | 2 |

| Rabat | Morocco | The Embassy of Canada to Morocco | 2 |

| Reykjavik | Iceland | The Embassy of Canada to Iceland | 3 |

| Riga | Latvia | The Embassy of Canada to Latvia | 3 |

| Riyadh | Saudi Arabia | The Embassy of Canada to Saudi Arabia | 2 |

| Rome | Italy | The Embassy of Canada to Italy | 1 |

| Stockholm | Sweden | The Embassy of Canada to Sweden | 2 |

| Tel Aviv | Israel | The Embassy of Canada to Israel | 2 |

| Tripoli | Libya | The Embassy of Canada to Libya | 3 |

| Tunis | Tunisia | The Embassy of Canada to Tunisia | 2 |

| Vatican City | Holy See | The Embassy of Canada to the Holy See | 2 |

| Vienna | Austria | The Embassy of Canada to Austria | 1 |

| Warsaw | Poland | The Embassy of Canada to Poland | 2 |

| Zagreb | Croatia | The Embassy of Canada to Croatia | 3 |

Total: 42

High Commissions (HC)

| Mission | Country | Designation / Title | Category Common (property) |

|---|---|---|---|

| London | United Kingdom | The High Commission of Canada to the United Kingdom | 1 |

Total: 1

Embassy / High Commission of Canada (Program) (PO)

| Mission | Country | Designation / Title | Category Common (property) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bratislava | Slovakia | The Office of the Embassy of Canada, Bratislava | 4 |

| Tallinn | Estonia | The Office of the Embassy of Canada, Tallinn | 4 |

| Vilnius | Lithuania | The Office of the Embassy of Canada, Vilnius | 4 |

Total: 3

Offices of the Embassy / High Commission (O)

| Mission | Country | Designation / Title | Category |

|---|---|---|---|

| Barcelona | Spain | The Consulate and Trade Office of Canada, Barcelona | 4 |

| Erbil | Iraqi Kurdistan | The Office of the Canadian Embassy, Erbil | 3 |

Total: 2

Representative Offices (RO)

| Mission | Country | Designation / Title | Category |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ramallah | West Bank & Gaza | Representative Office of Canada, Ramallah | 4 |

Total: 1

Australian (A), Canadian Commercial Corporation (CCC) & Other Offices (O)

| Mission | Country | Designation / Title | Category |

|---|---|---|---|

Total: 0

Multilaterals (M)

| Mission | Country | Designation / Title | Category |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brussels EU | Belgium | The Mission of Canada to the European Union | 1 |

| Brussels NATO | Belgium | Canadian Joint Delegation to the North Atlantic Council | 1 |

| Geneva PERM | Switzerland | The Permanent Mission of Canada to the Office of the United Nations and to the Conference on Disarmament | 1 |

| Geneva WTO | Switzerland | The Permanent Mission of Canada to the World Trade Organization | 1 |

| Paris OECD | France | The Permanent Delegation of Canada to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development | 2 |

| Paris UNESCO | France | The Permanent Delegation of Canada to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization | 2 |

| Vienna OSCE | Austria | Canadian delegation to the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe | 3 |

| Vienna PERM | Austria | The Permanent Mission of Canada to the International Organizations (IAEA, CBTBO, UNODC/UNOV) | 3 |

Total: 8

Consulates General (CG)

| Mission | Country | Designation / Title | Category |

|---|---|---|---|

| Istanbul | Turkey | The Consulate General of Canada, Istanbul | 4 |

| Dubai | United Arab Emirates | The Consulate General of Canada, United Arab Emirates | 3 |

Total: 2

Consulates (C)

| Mission | Country | Designation / Title | Category |

|---|---|---|---|

| Düsseldorf | Germany | The Consulate of Canada, Düsseldorf | 4 |

| Munich | Germany | The Consulate of Canada, Munich | 4 |

Total: 2

Consular Agencies (CA)

| Mission | Country | Designation / Title | Category |

|---|---|---|---|

Total: 0

Consulates headed by an Honorary Consul

| Point of Service | Country | Status |

|---|---|---|

| Belfast | United Kingdom | Active |

| Bishkek | Kyrgyz Republic | Active |

| Cardiff | United Kingdom | Active |

| Edinburgh | United Kingdom | Active |

| Faro | Portugal | Active |

| Flanders | Belgium | Active |

| Gothenburg | Sweden | Active |

| Jeddah | Saudi Arabia | Active |

| Liège | Belgium | Active |

| Ljubljana | Slovenia | Active |

| Luxembourg | Luxembourg | Active |

| Lviv | Ukraine | Active |

| Lyon | France | Active |

| Malaga | Spain | Active |

| Manama | Bahrain | Active |

| Milan | Italy | Active |

| Monaco | Monaco | Active |

| Muscat | Oman | Active |

| Nice | France | Active |

| Nicosia | Cyprus | Active |

| Nuuk | Greenland | Active |

| Ponta Delgada | Portugal | Active |

| Reykjavic | Iceland | Active |

| Sana'a | Yemen | Active |

| Skopje | Macedonia | Active |

| Sofia | Bulgaria | Active |

| Stavanger | Norway | Active |

| St. Pierre and Miquelon | France | Active |

| Stuttgart | Germany | Active |

| Tashkent | Uzbekistan | Active |

| Tbilisi | Georgia | Active |

| Thessaloniki | Greece | Active |

| Tirana | Albania | Active |

| Toulouse | France | Active |

| Valletta | Malta | Active |

| Vladivostok | Russia Federation | Active |

| Yerevan | Armenia | Active |

Total: 37

Total Europe & Middle East: 98

Asia Pacific

Embassies (E)

| Mission | Country | Designation / Title | Category |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bangkok | Thailand | The Embassy of Canada to Thailand | 2 |

| Beijing | China | The Embassy of Canada to China | 1 |

| Hanoi | Vietnam | The Embassy of Canada to Vietnam | 2 |

| Jakarta | Indonesia | The Embassy of Canada to Indonesia | 2 |

| Kabul | Afghanistan | The Embassy of Canada to Afghanistan | 3 |

| Manila | Philippines | The Embassy of Canada to the Philippines | 2 |

| Seoul | Korea, South | The Embassy of Canada to the Republic of Korea | 2 |

| Tokyo | Japan | The Embassy of Canada to Japan | 1 |

| Ulaanbaatar | Mongolia | The Embassy of Canada to Mongolia | 3 |

| Yangon | Burma | The Embassy of Canada to Burma | 4 |

Total: 10

High Commissions (HC)

| Mission | Country | Designation / Title | Category |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bandar Seri Begawan | Brunei | The High Commission of Canada to Brunei Darussalam | 4 |

| Canberra | Australia | The High Commission of Canada to Australia | 2 |

| Colombo | Sri Lanka | The High Commission of Canada to Sri Lanka | 3 |

| Dhaka | Bangladesh | The High Commission of Canada to Bangladesh | 2 |

| Islamabad | Pakistan | The High Commission of Canada to Pakistan | 2 |

| Kuala Lumpur | Malaysia | The High Commission of Canada to Malaysia | 2 |

| New Delhi | India | The High Commission of Canada to India | 1 |

| Singapore | Singapore | The High Commission of Canada to Singapore | 2 |

| Wellington | New Zealand | The High Commission of Canada to New Zealand | 2 |

Total: 9

Embassy / High Commission of Canada (Program) (PO)

| Mission | Country | Designation / Title | Category |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phnom Penh (1 Sept 2015) | Cambodia | The Office of the Embassy of Canada, Thailand | 4 |

| Vientiane (1 Sept 2015) | Laos | The Office of the Embassy of Canada, Thailand | 4 |

Total: 2