This is a past issue of the State of Trade. For the latest report, please visit Canada’s State of Trade reports.

State of Trade 2021 - A closer look at Foreign Direct Investment (FDI)

ISSN 2562-8321

Table of contents

- Message from Minister Ng

- Acronyms

- Executive Summary

- Chapter 1: 2020 in review

- Chapter 2: FDI as a driver of domestic growth

- Chapter 3: Why do companies invest abroad?

- Chapter 4: Attracting FDI— showcasing Canada's strengths

- Bibliography

- Data sources

Message from Minister Ng

This report captures the story of the incredible sacrifices made and resilience demonstrated by Canadians and businesses through an unparalleled chapter in our country's history, and charts a path forward as we step into our recovery from the COVID-19.

With the unprecedented restrictions and challenges of this pandemic, there is no doubt that 2020 was a difficult year for all Canadians—from workers and businesses to families and economy.

Waves of COVID-19, public health measures, and restricted travel around the world, brought economic challenges. Canadians stepped up to the challenges, working together to address this crisis with compassion and kindness.

Our government's COVID-19 Economic Response Plan represented the most significant investments to support Canadians from the Government of Canada since the second world war. It was instrumental in protecting millions of jobs, ensuring families didn't have to make impossible choices between paying their bills and putting food on the table, and supporting businesses to keep their lights on, cover costs, and keep employees on their payroll.

We have been focused on ensuring we addressed the significant social and economic impacts of the pandemic since day one – moving quickly to introduce crucial emergency business supports and working internationally to accelerate the production and equitable distribution of critical medical supplies, such as personal protective equipment and ventilators, and vaccines to protect Canadians and people around the world.

In addition to crucial emergency support programs, we have used every tool in our toolbox to bridge businesses through the pandemic and into recovery.

Whether it's been through virtual trade missions around the world or our fifteen free trade agreements giving businesses access to 1.5 billion customers around the world -- we haven't let COVID-19 stop us from trading. We have continued to create opportunities for businesses to trade—opportunities which will be crucial to growth and jobs and we work to recover as quickly as possible.

Canada's State of Trade makes two things clear: Canadians and businesses made significant sacrifices during COVID-19, and in our recovery, trade and investment will be critical to generating inclusive, sustainable growth, creating jobs, and building a stronger, more resilient future.

That is why in Budget 2021 we are investing in making historic, necessary investments of over $100 billion over three years for our economic recovery. Now is the time to restore business confidence, create jobs, ensure sustainable and inclusive growth that benefits all Canadians including women, Indigenous and racialized entrepreneurs, and keeps our global supply chains open and resilient.

With our strong, stable and resilient economy; welcoming business environment, high standards for labour, the environment, and inclusivity; and skilled, diverse and well-educated workforce; Canada is set up for success as we recover from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Moving forward, we will continue to work with our partners around the world to forge a path to a clear, strong, and equitable economic recovery. The best way for us to achieve this is by finishing this fight against COVID-19 and facing any challenges that may lay ahead of us, together, as one Team Canada.

Our commitment in giving Canadian businesses the stability they need to thrive and grow around the world is unwavering. It's time to build back better, and together we will succeed.

- The Honourable Mary Ng, Minister of Small Business, Export Promotion and International Trade

Acronyms

- $B

- Billion dollars

- $M

- Million dollars

- AAFC

- Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada

- AI

- Artificial intelligence

- BDC

- Business Development Bank of Canada

- Can$

- Canadian dollar

- CCCA

- Consider Canada City Alliance

- CDIA

- Canadian direct investment abroad

- CETA

- Canada-European Union Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement

- CGE

- Computable General Equilibrium model

- CMA

- Canadian mining assets

- CMNE

- Canadian multinational enterprise

- CN

- Canadian National Railway

- CKFTA

- Canada-Korea Free Trade Agreement

- CPTPP

- Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership

- CUSMA

- Canada-United States-Mexico Agreement

- EDC

- Export Development Canada

- EU

- European Union

- EV

- Electric vehicle

- FDI

- Foreign direct investment

- FTA

- Free trade agreement

- FMNE

- Foreign multinational enterprise

- GAC

- Global Affairs Canada

- GDP

- Gross domestic product

- GFC

- Global Financial Crisis

- HS

- Harmonized System

- ICA

- Investment Canada Act

- ICT

- Information and communication technologies

- IIC

- Immediate investing country

- IMF

- International Monetary Fund

- IPA

- Investment promotion agencies

- ISED

- Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada

- KPI

- Key performance indicator

- LNG

- Liquefied natural gas

- M&A

- Mergers and acquisitions

- M&E

- Machinery and equipment

- MNE

- Multinational enterprise

- NAFTA

- North American Free Trade Agreement

- NAICS

- North American Industry Classification System

- NRCan

- Natural Resources Canada

- OCE

- Office of the Chief Economist, Global Affairs Canada

- OECD

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

- OE

- Oxford Economics

- OLI

- Ownership, location, and internalization

- pp

- Percentage point

- PPE

- Personal protective equipment

- R&D

- Research and development

- SAAR

- Seasonally adjusted annual rate

- SIBS

- Survey of Innovation and Business Strategy

- SIF

- Strategic Innovation Fund

- SME

- Small and medium-sized enterprise

- SPE

- Special purpose entity

- SR&ED

- Scientific Research and Experimental Development

- STEM

- Science, technology, engineering, and mathematics

- TCS

- Trade Commissioner Service

- UHC

- Ultimate host country

- UIC

- Ultimate investor country

- U.K.

- United Kingdom

- UNCTAD

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development

- U.S.

- United States (used adjectivally)

- US$

- United States dollar

- VTM

- Virtual trade mission

- WEO

- World Economic Outlook

- WTO

- World Trade Organization

Executive summary

The year 2020 was one of the most tumultuous in modern history with the COVID-19 pandemic wreaking havoc worldwide, impacting every area of people's lives. Following 2019, a year marked by the slowest annual growth in world GDP since the 2008-2009 global financial crisis (GFC), 2020 began with an already elevated level of uncertainty due to trade disputes, geopolitical tensions, and social unrest. Not long into the year, a rapidly spreading viral disease had taken centre stage. By mid-March, this initially localized health crisis had been declared a pandemic, on its way to becoming one of the greatest global disasters in our lifetime.

The Canadian economy was hit hard, experiencing its largest quarterly declines since comparable data were available, contracting by 7.9% (annualized) in the first quarter of 2020 and another 38% in Q2 (annualized). As the first wave of the pandemic passed and restrictions were relaxed, a rapid recovery followed—the economy expanded by 42% in the third quarter (annualized), the fastest quarterly expansion on record. The rebound in Canada's economic activities slowed down to 9.3% (annualized) in the fourth quarter, as rising cases led to a second wave of lockdowns in affected regions.

The strong recovery in the second half of 2020 was not enough to offset the loss in the first half though, with many services-producing industries continuing to struggle by the end of the year. Overall, Canada's gross domestic product (GDP) contracted by 5.3% in 2020, its largest annual contraction on record. The pandemic also had a profound impact on the labour market. For the full year, Canadian employment declined by 5.2% or nearly 1 million jobs, leading to Canada's annual unemployment rate rising to 9.5%.

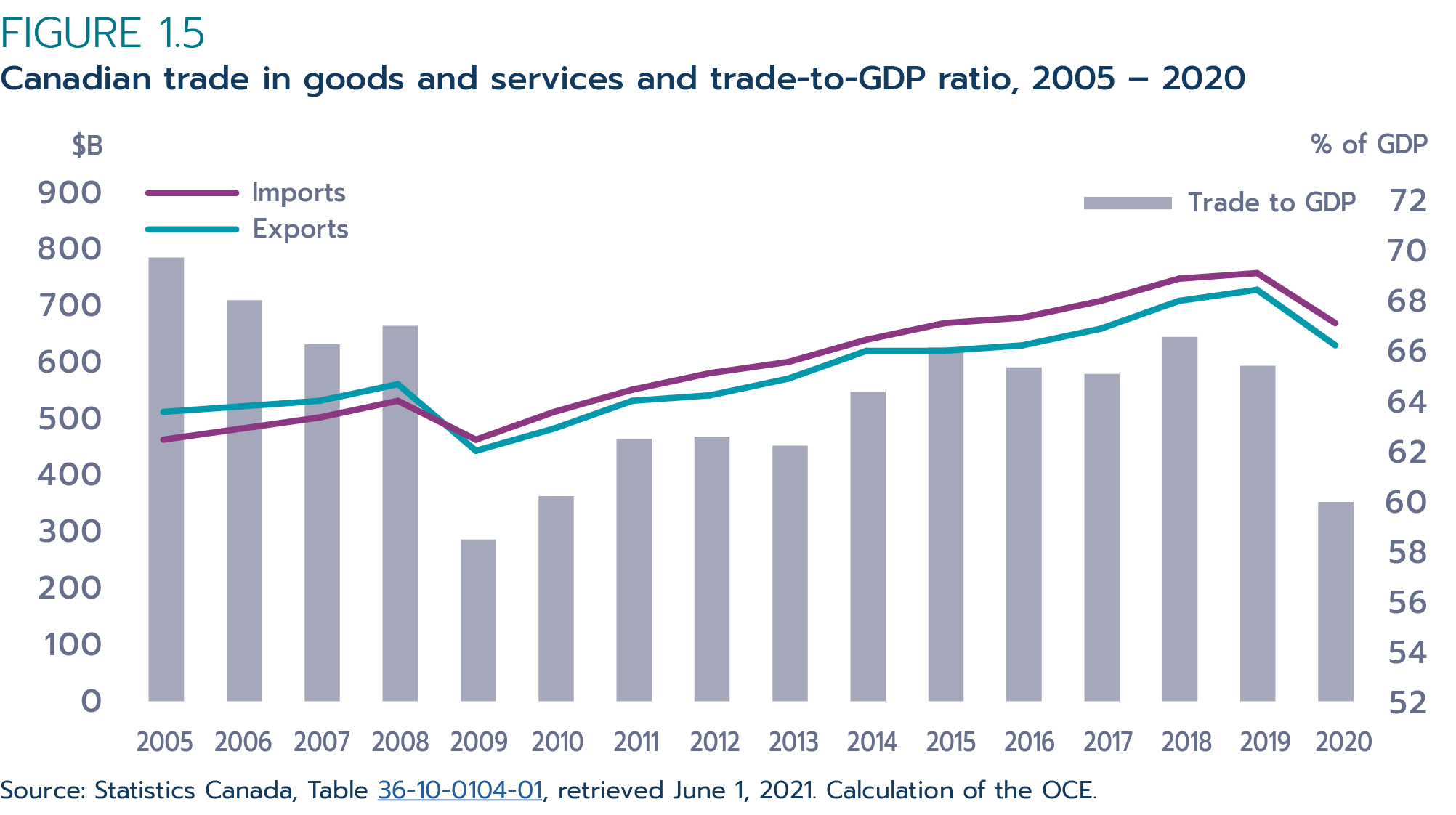

Year-over-year, Canada's total trade in goods and services fell by 13% to $1.3 trillion in value the second-fastest 1-year decline on record, after the 17% contraction following the GFC, from 2008 to 2009. Both exports and imports recorded double-digit declines, down 13% and 12%, respectively. This was mainly due to lower bilateral trade with the United States. Canada's trade-to-GDP ratio dropped from 65% in 2019 to 60% in 2020—also the lowest since 2009.

In 2020, overall Canadian trade in goods contracted by 10%. Goods exports were more affected, falling by 12% to $524 billion in value, compared to imports, which shrank 8.5% to $561 billion. The impact on services industries was especially dire, particularly on those that depend on face-to-face interactions, like the tourism and hospitality industries. For the full year, Canadian services trade fell by over a fifth in value to $237 billion, with services exports declining by 18% and services imports falling by 24%.

Canada's foreign investment performance was also severely impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, with both flows of inward foreign direct investment (FDI) and Canadian direct investment abroad (CDIA) registering large declines. For 2020 overall, Canadian FDI flows plummeted by 49% or $31 billion, and CDIA contracted 41% or $42 billion. While FDI flows are typically more volatile than trade or other economic measures, the magnitude of this 1-year decline is surpassed only by the 60% and 46% plunges in FDI and CDIA flows, respectively, in 2008-2009 due to the GFC. The decline in Canada's performance in attracting foreign direct investment in 2020 was roughly on par with that of the world.

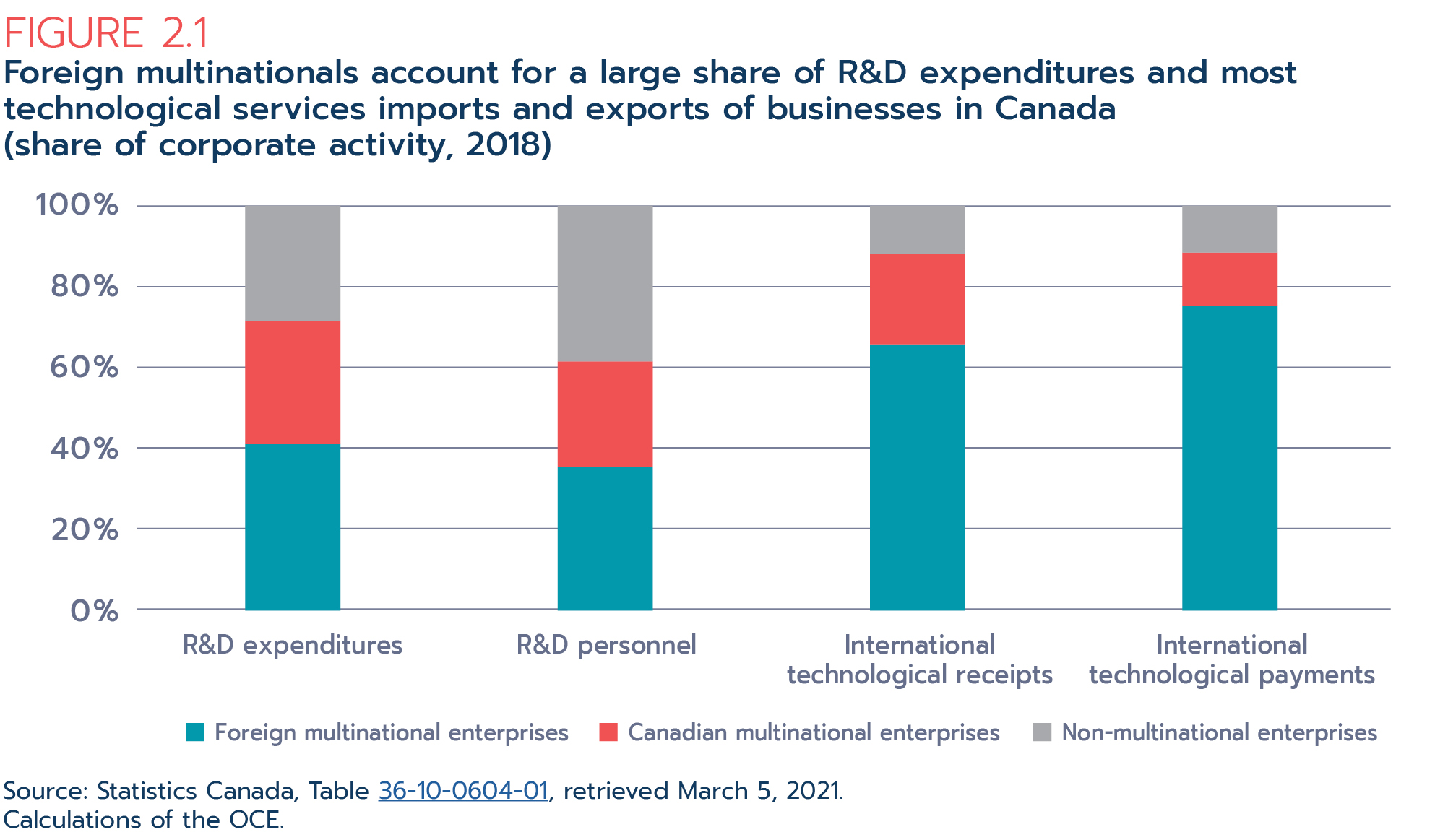

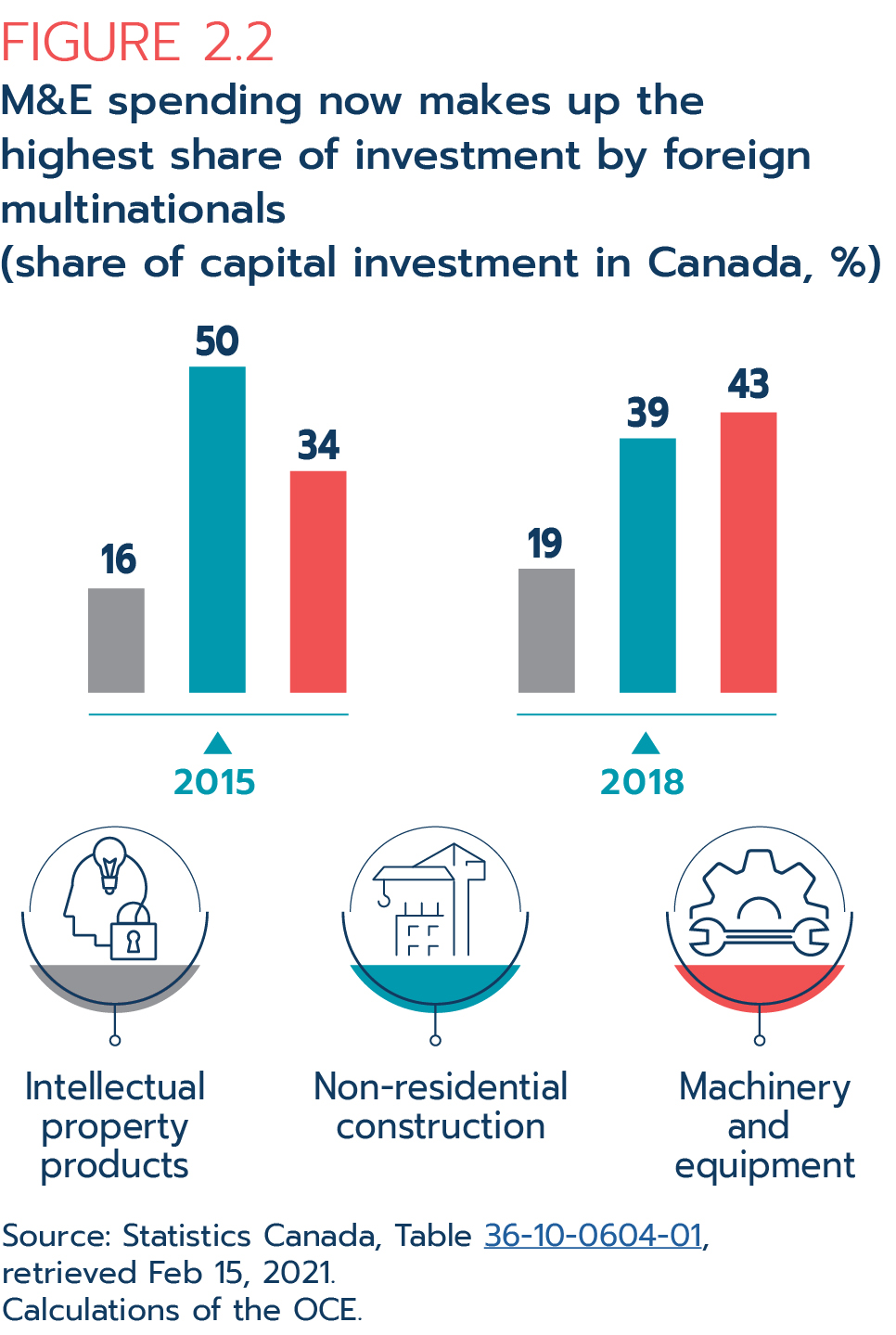

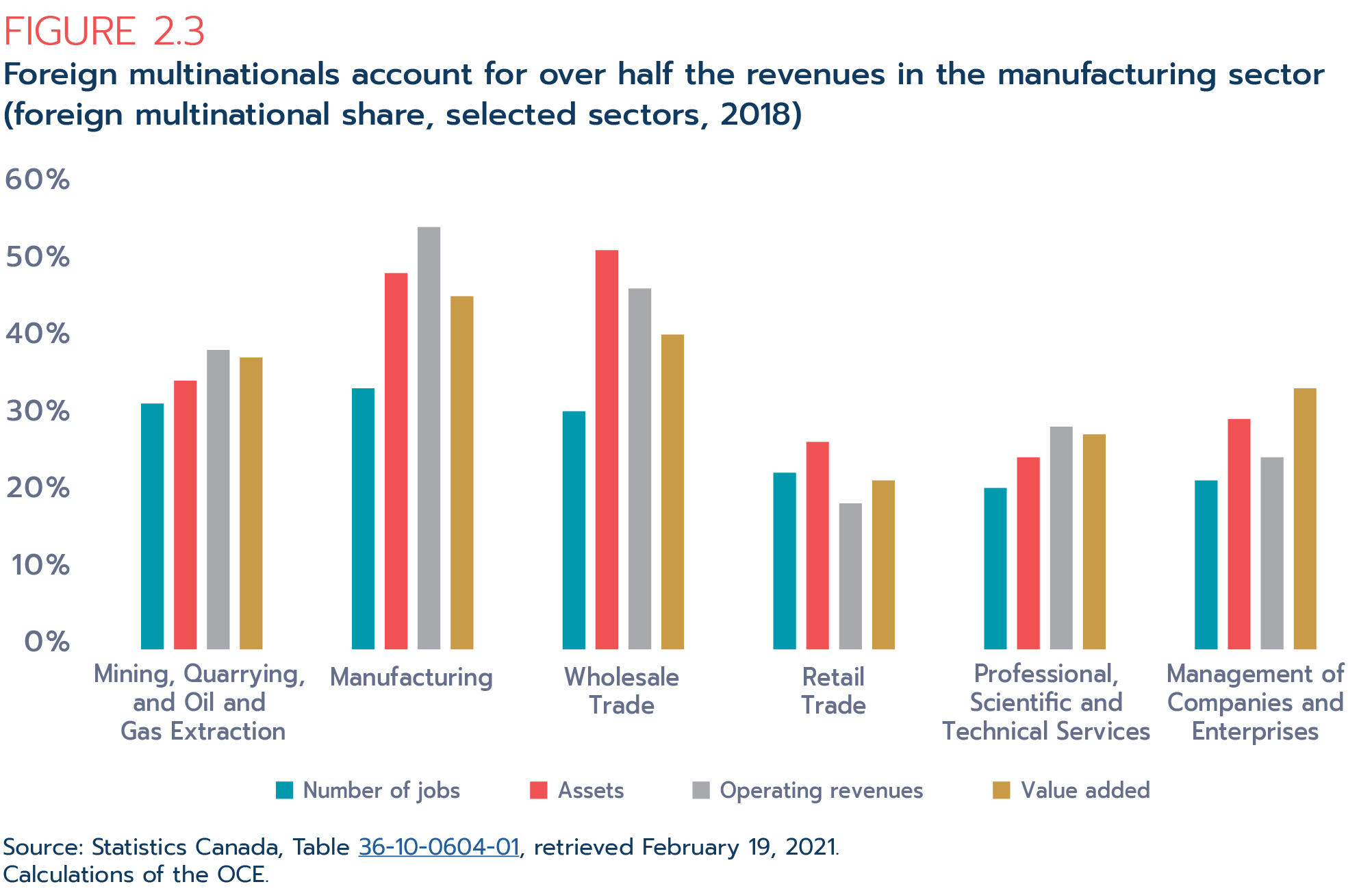

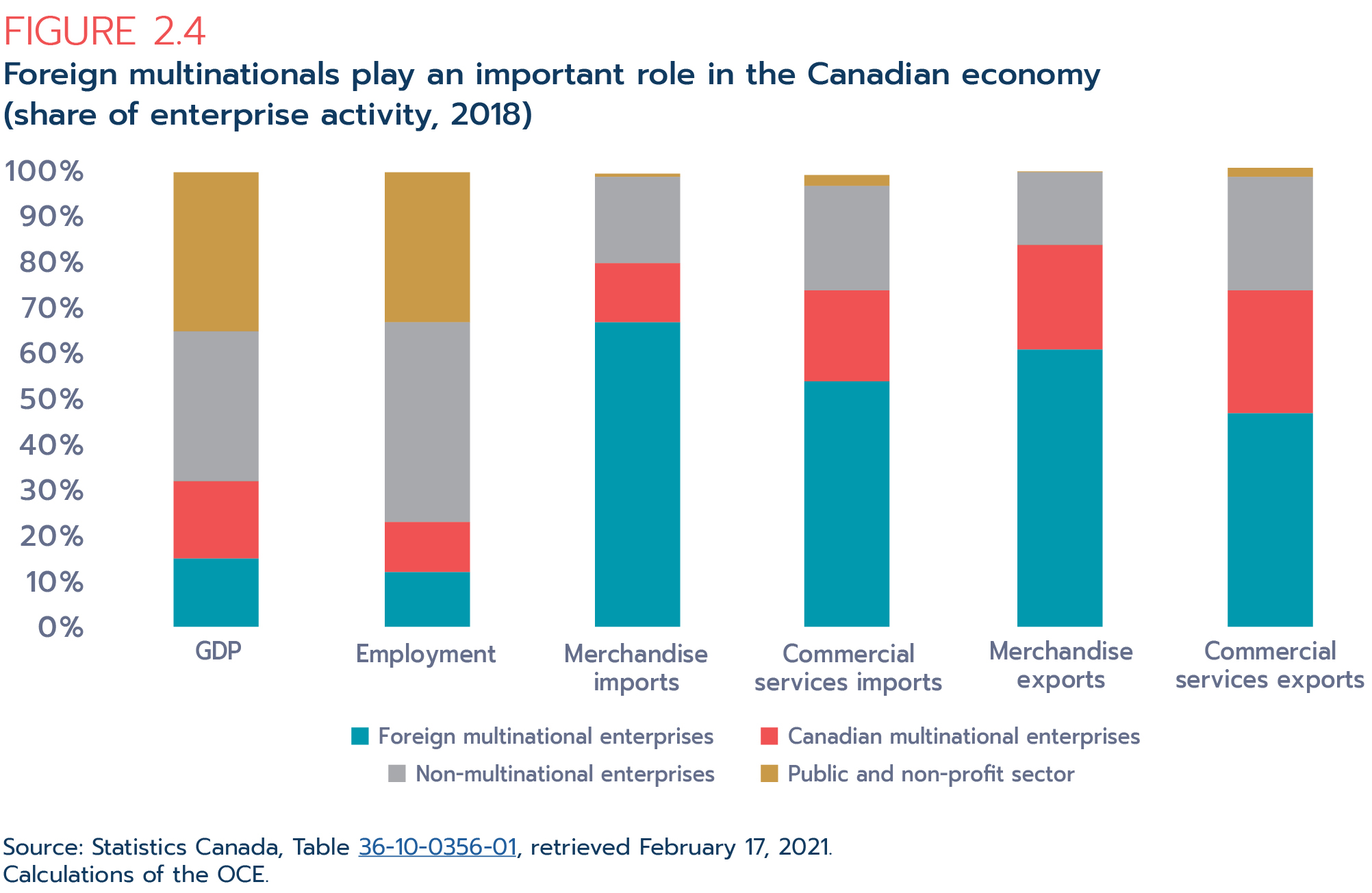

The devastation brought on by COVID-19 highlights the extent to which the world's economies are interconnected. It also serves as a reminder of the critical importance of trade and investment in sustaining economic growth and prosperity. Foreign multinationals (FMNEs) are essential to the Canadian economy. They represent less than 1% of companies in Canada yet account for 12% of all employment and 15% of GDP. Furthermore, FMNEs account for over 60% of trade in goods and services and hence contribute to Canada's integration to global supply chains and international trade. Foreign affiliates also foster competition among domestic companies, bring new technology and know-how, and contribute to skills upgrading in Canada's workforce.

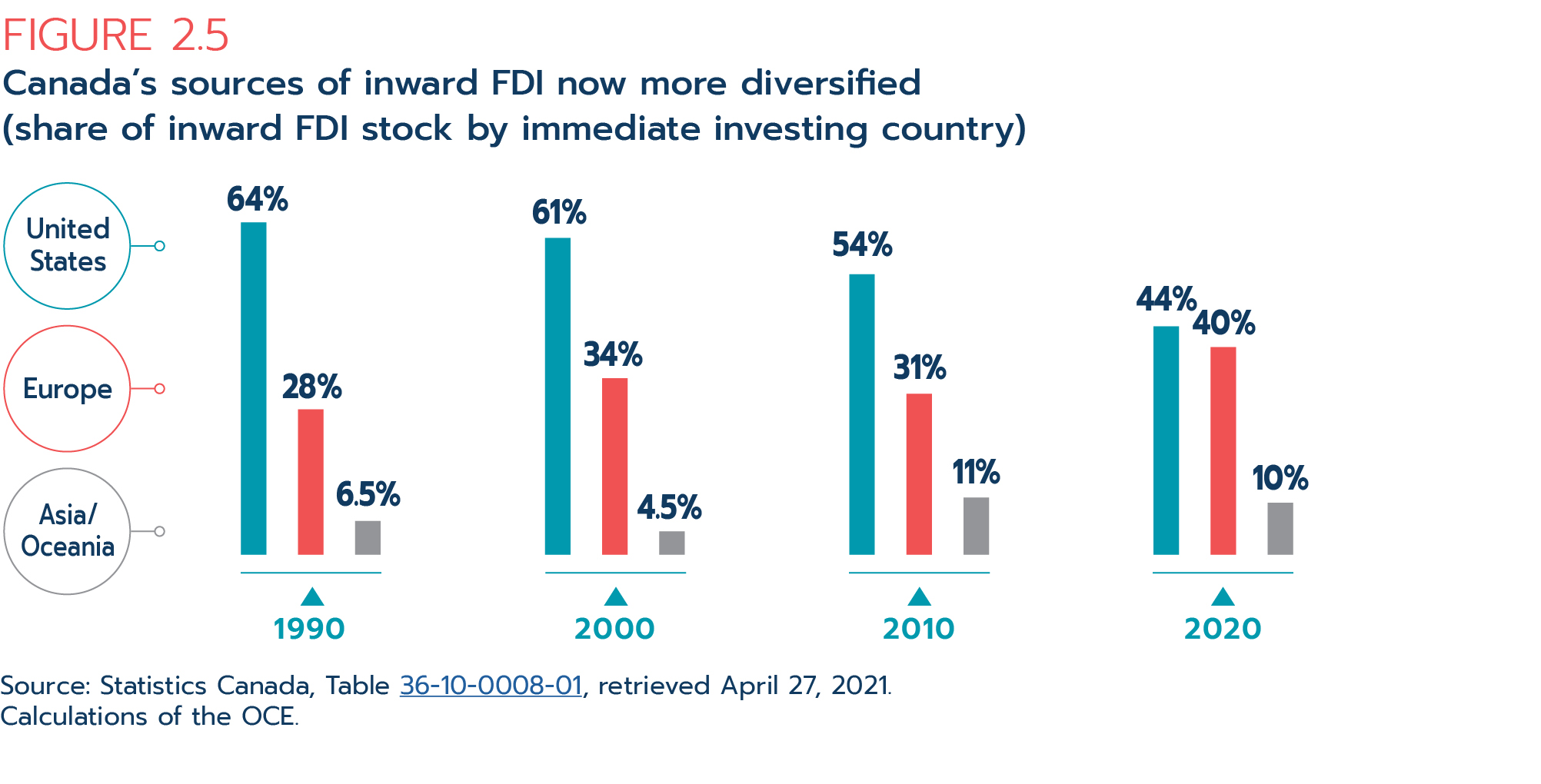

Just as trade diversification is vital in hedging risks from shocks, investment diversification is also key, helping to build connections worldwide and allowing Canadian businesses to take advantage of opportunities in fast-growing markets. Canada's inward FDI sources are now more geographically diverse, with Europe and Asia together accounting for the larger share of FDI stock. The U.S. now holds less than half of Canada's inward FDI stock. It is important to keep in mind, however, that among the top investing countries to Canada, the U.S., Japan and Germany ultimately invest more than traditional "immediate" investing country data suggest. A significant portion of their investments transit through intermediary countries before arriving in Canada. The investments are attributed to these intermediary countries in traditional FDI statistics, rather than to the original source countries.

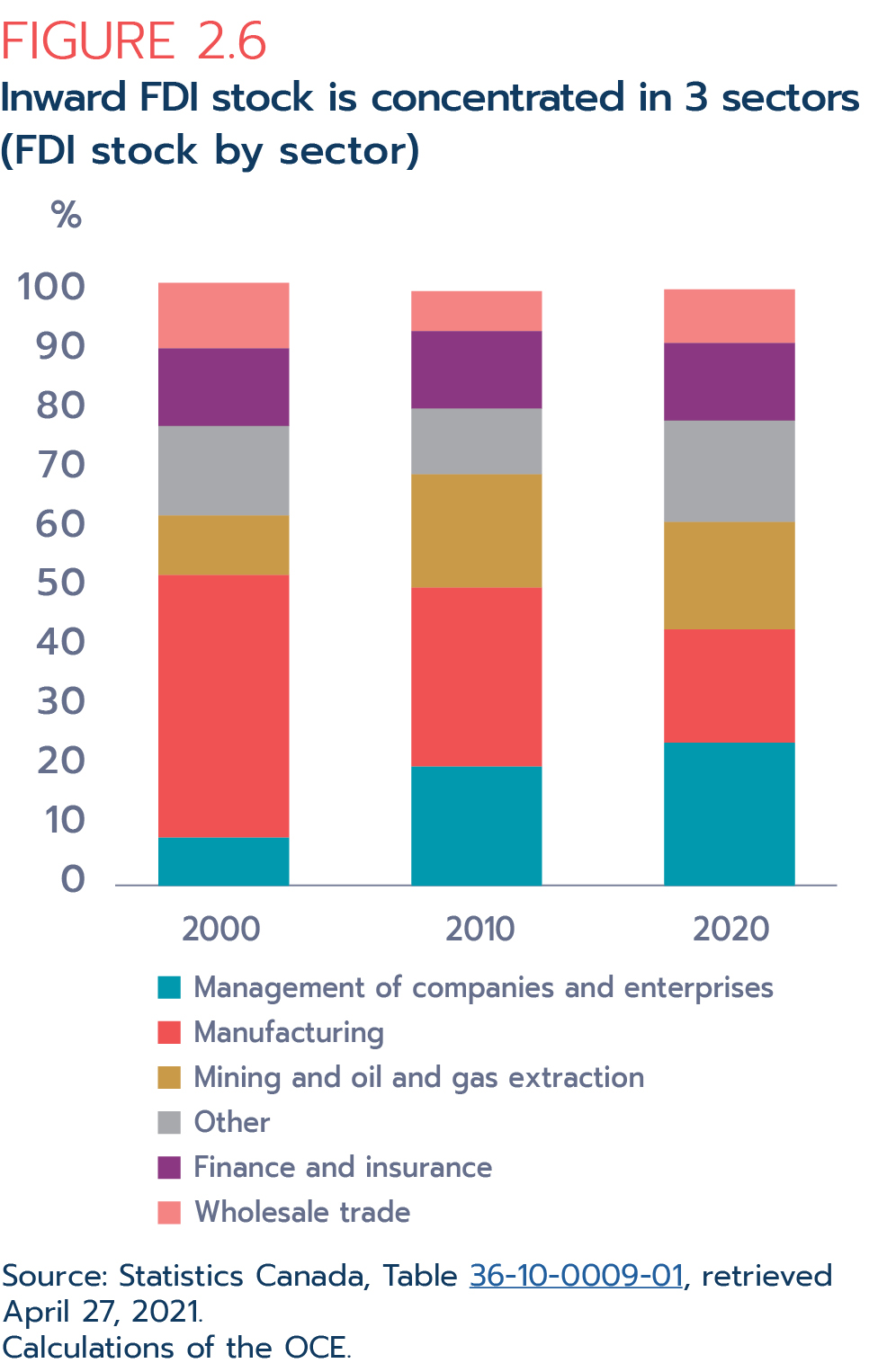

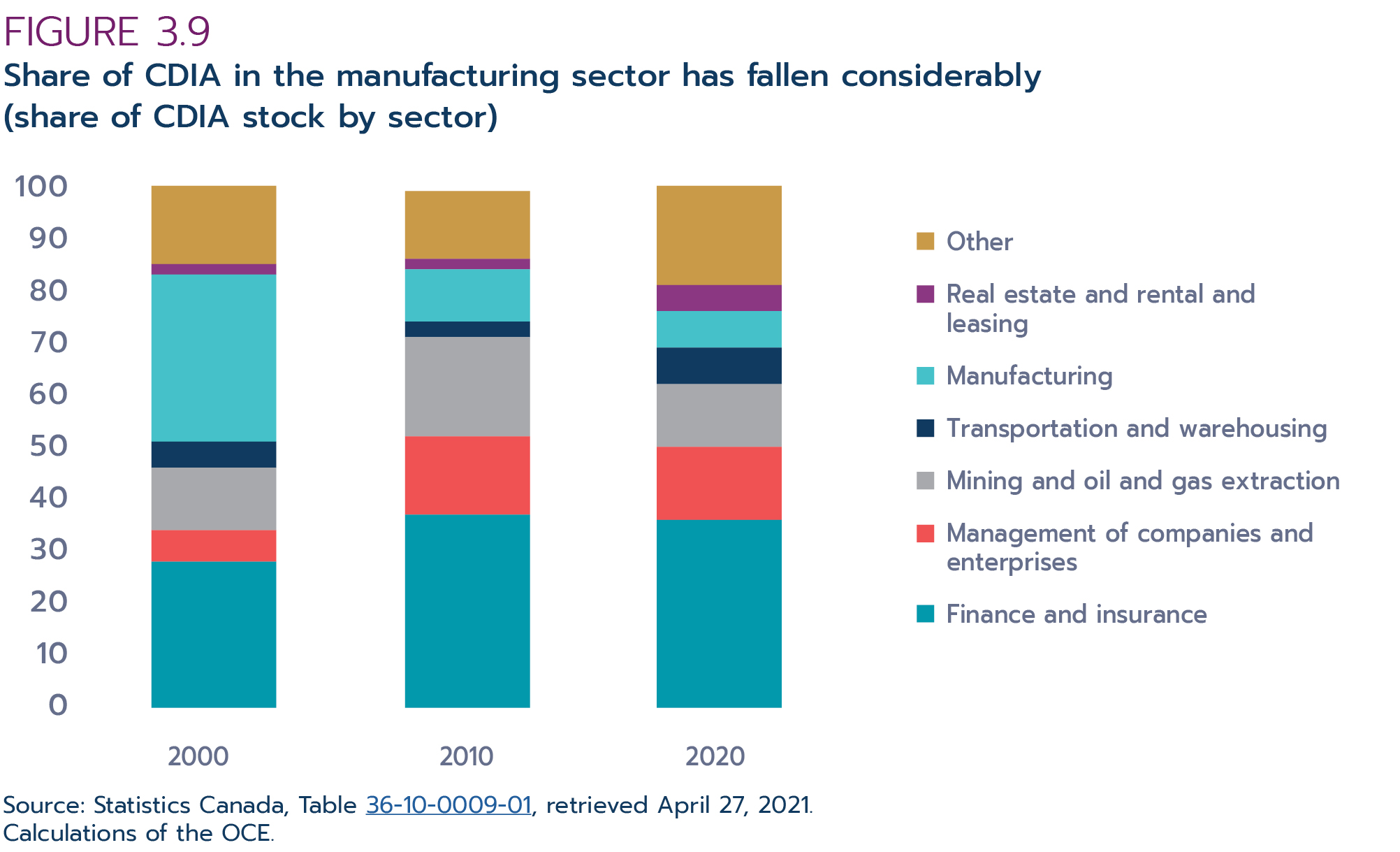

FDI data by industry reveal that most of the foreign capital in Canada is invested in 3 sectors: manufacturing; mining and oil and gas extraction; and management of companies and enterprises. The stock in Canada's manufacturing industry has fallen over the past 20 years. In 2000, the industry held close to 44% of FDI stock in Canada and in 2020 this share was 19%. Meanwhile, the total shares attributed to the mining and oil and gas extraction and management of companies and enterprises sectors have grown. In 2020, just under one quarter of FDI stock was in the management of companies and enterprises sector, while the mining and oil and gas extraction sector accounted for 18% of the total.

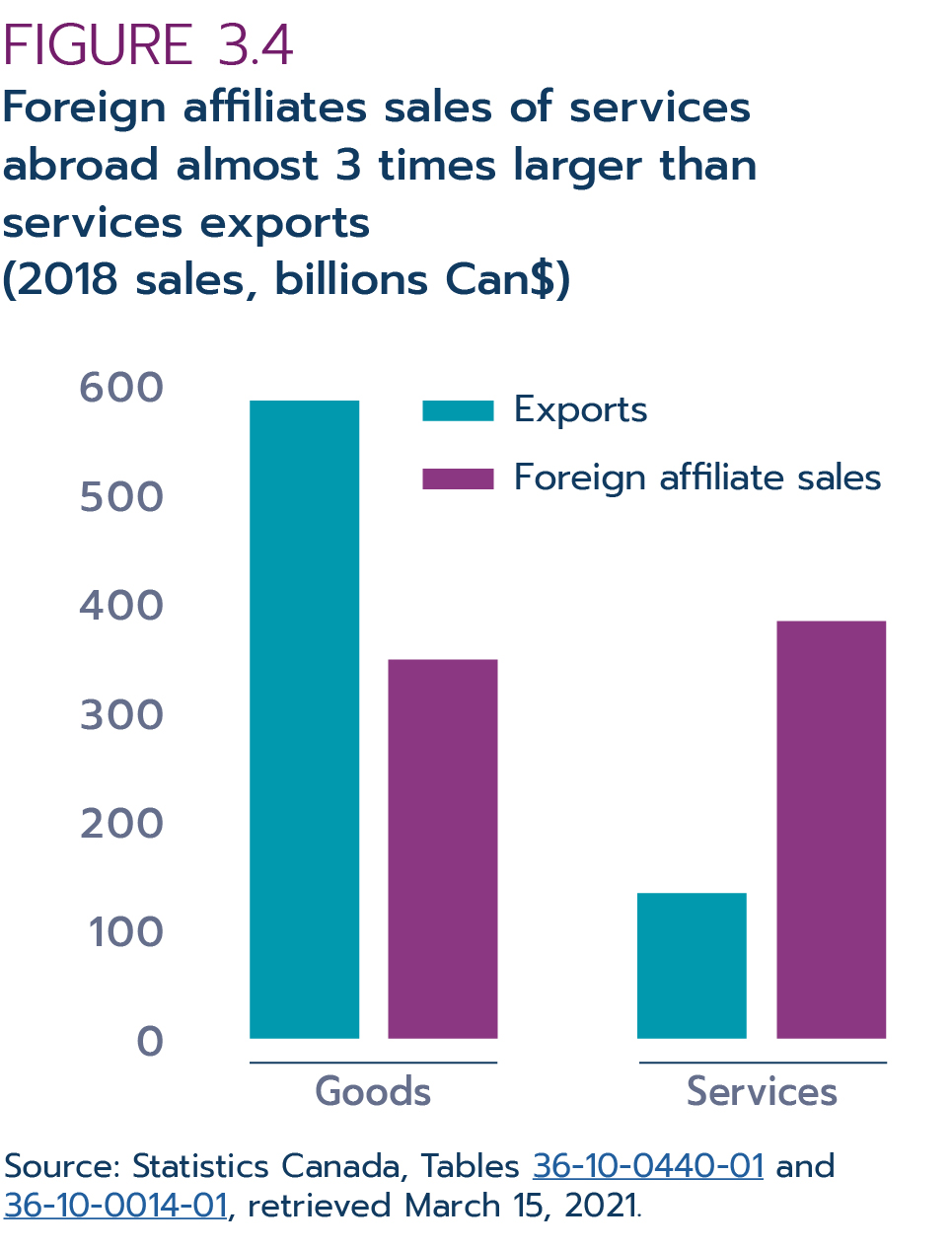

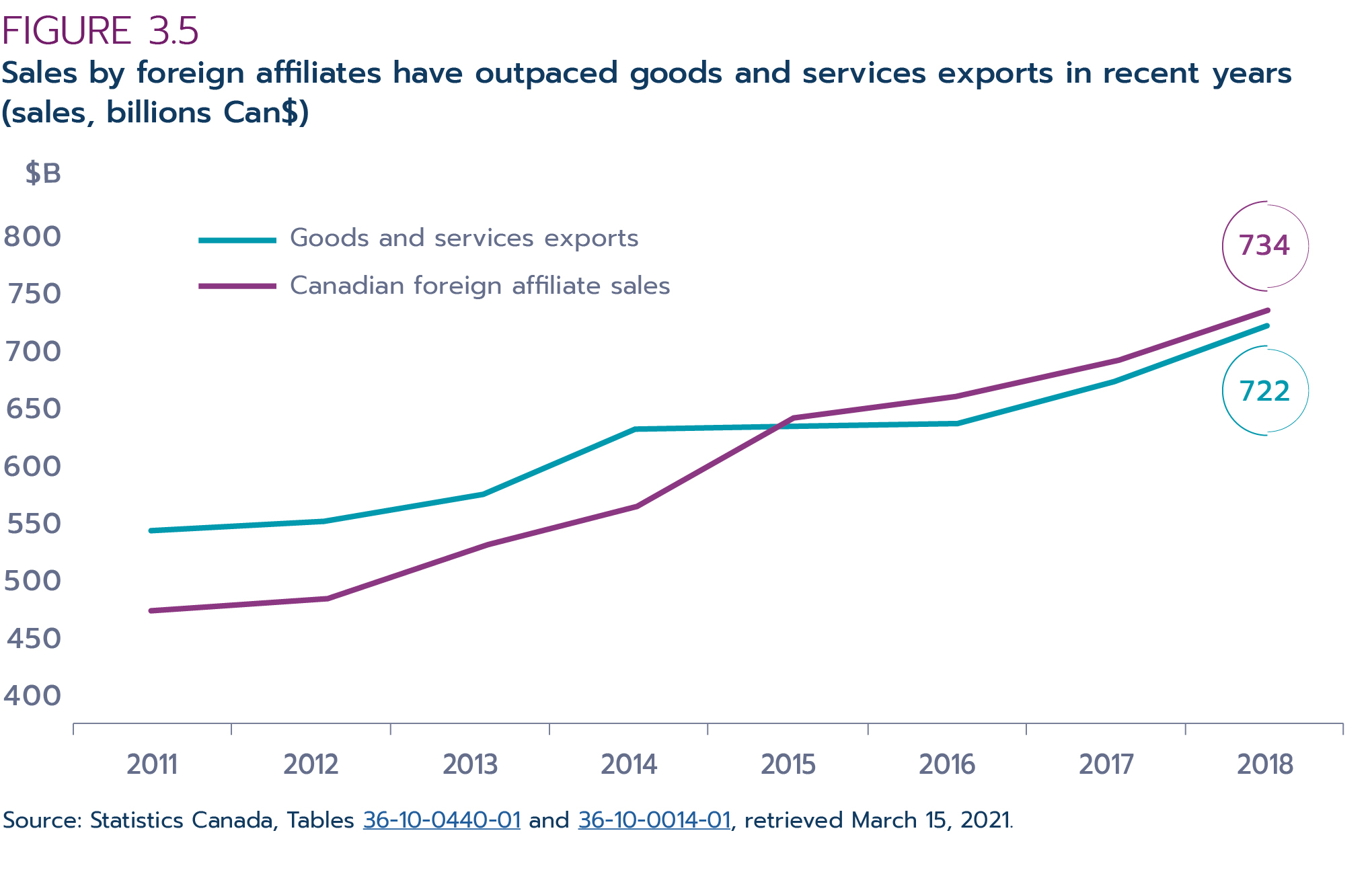

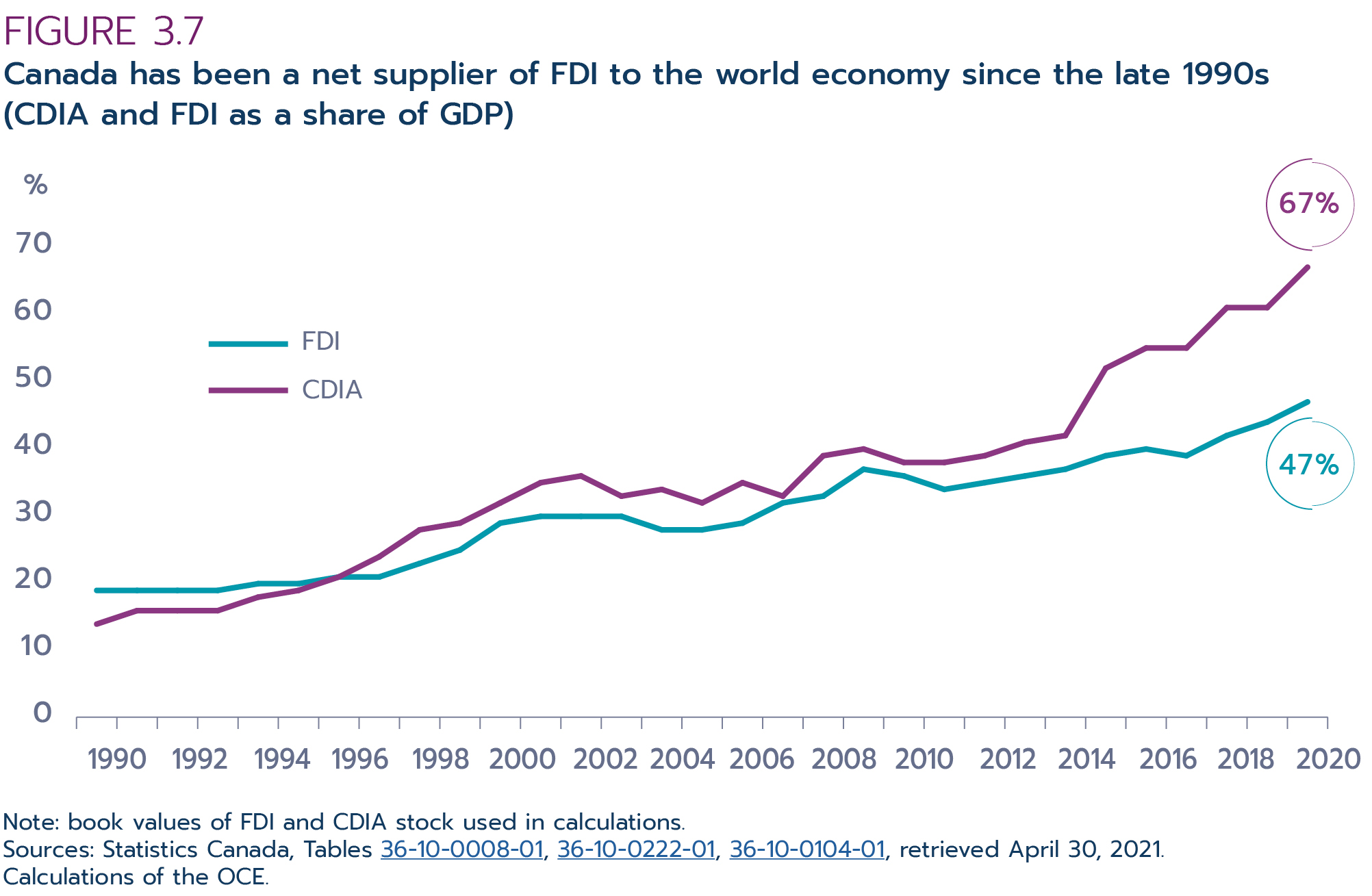

Outward FDI, or CDIA, has come to play an increasingly important role in the Canadian economy. A key reason for establishing foreign affiliates is to increase sales by accessing new markets and gaining proximity to key customers. Sales by foreign affiliates outpaced goods and services exports in recent years, and roughly three quarters of the growth in foreign affiliate sales between 2011 and 2018 came from service sector industries. The services sector now accounts for the majority of foreign affiliate sales. Furthermore, sales by foreign affiliates in the services sector far exceed exports in this sector. This underscores the fact that having a local presence is especially important for foreign sales of services.

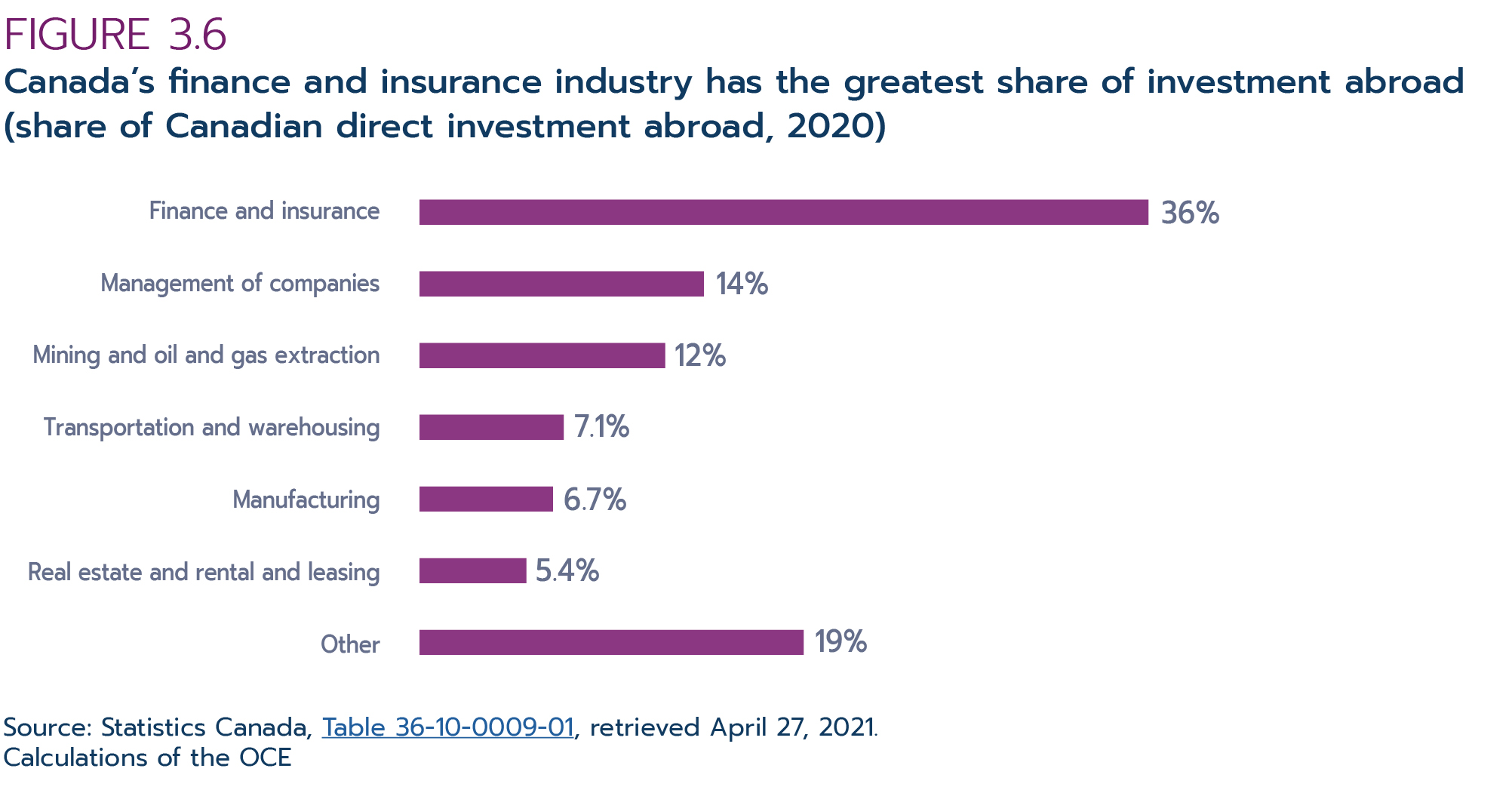

The finance and insurance services industry has accounted for the largest share of CDIA stock since the early 2000s. The industry now makes up over a third of Canada's total direct investment abroad. The management of companies and enterprises industry is the second largest, making up less than a sixth of the total, closely followed by mining and oil and gas extraction.

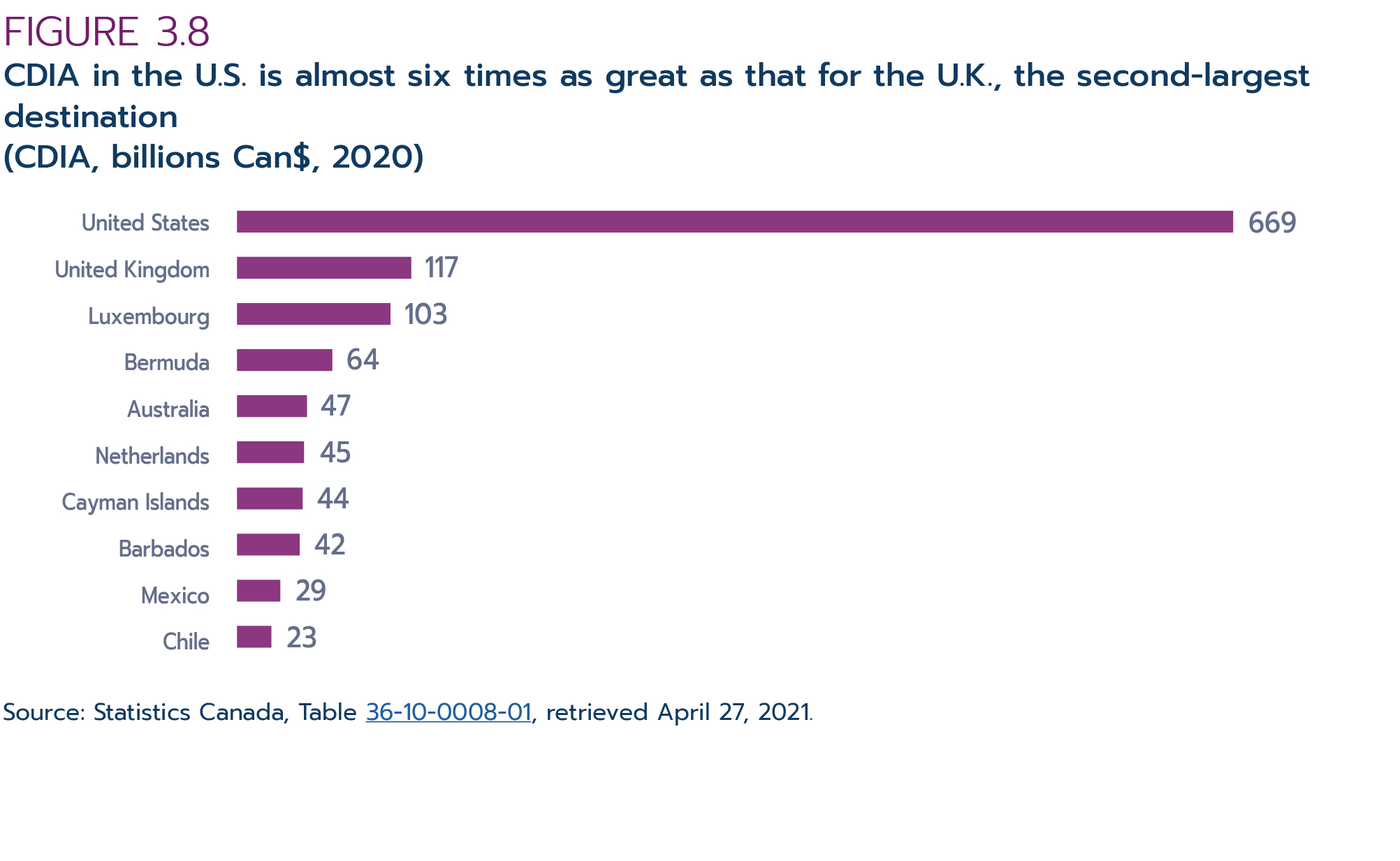

Not surprisingly, the top destination for CDIA is the United States. The U.S. has almost 6 times more CDIA stock than the second-largest destination, the United Kingdom. The U.K., Luxembourg and the Netherlands are the main European destinations. Interestingly, a number of Caribbean economies are among the top 10 destinations of CDIA: Bermuda, the Cayman Islands, and Barbados. Canadian investments in the Caribbean countries, and possibly to some extent in Luxembourg and the Netherlands, primarily transit through these offshore financial centres though they are typically destined to other countries.

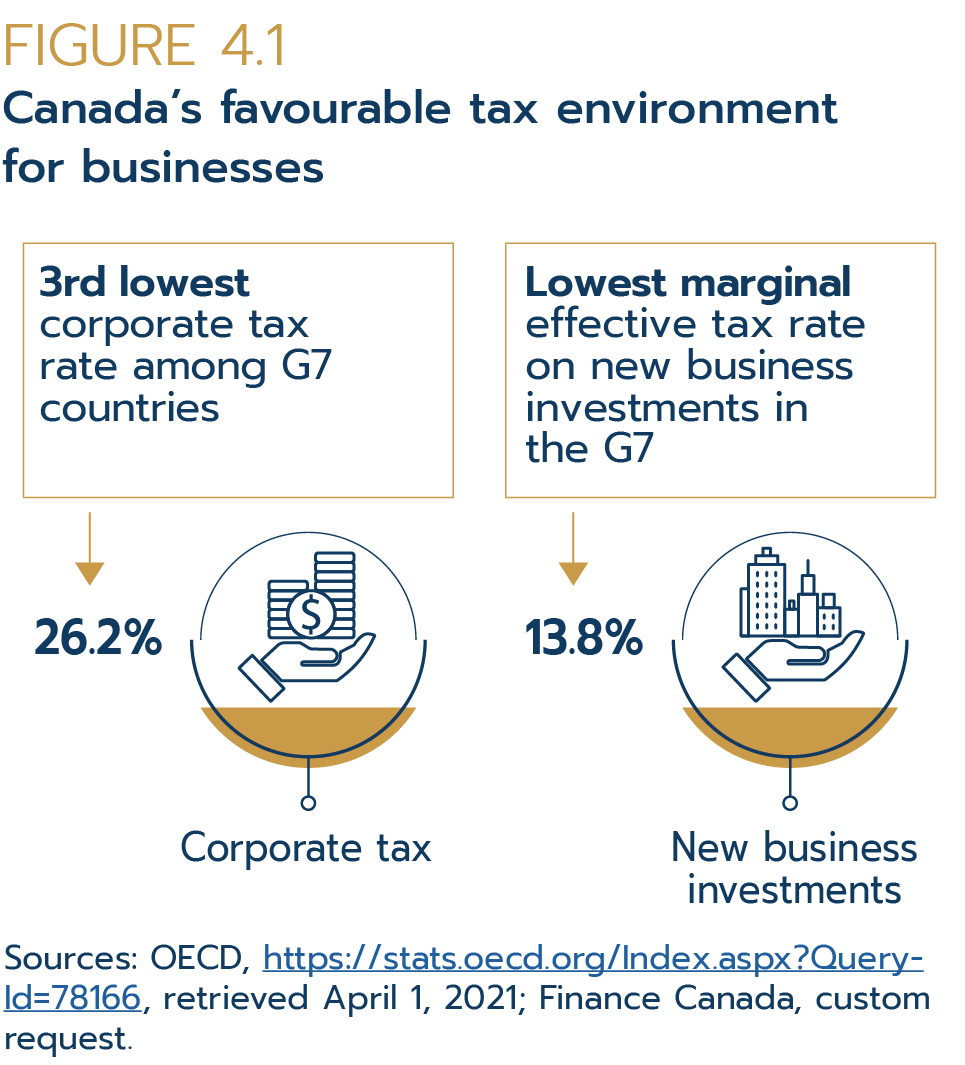

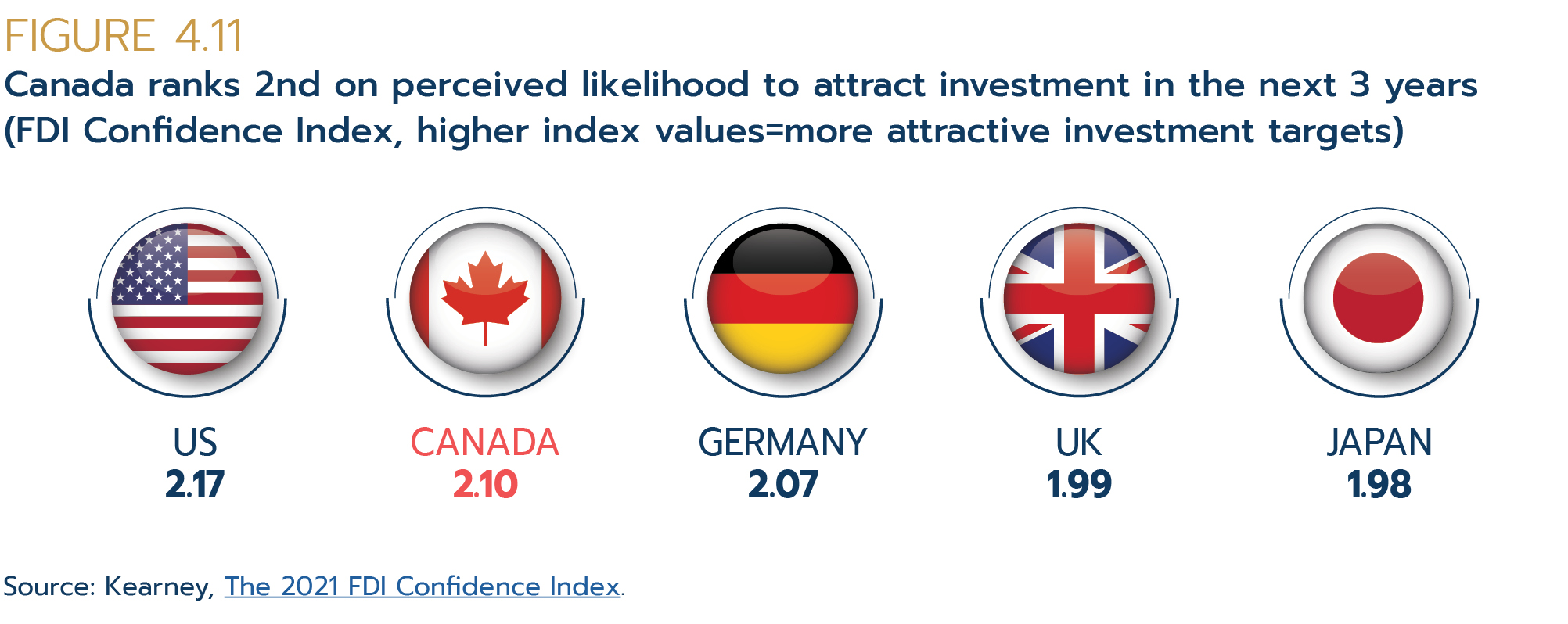

Attracting FDI is vital to the growth, prosperity and resilience of Canada's cities, provinces and industries and the overall Canadian economy. This rings especially true now and will continue to do so in the wake of the pandemic. FDI attraction involves competing on a global scale and promoting Canada's strengths as an investment destination. Key factors that make Canada an attractive place to invest include its strong, stable and resilient economy; welcoming business environment; highly educated, skilled and diverse labour force; well-developed innovation ecosystem; extensive market access; and overall high quality of life.

The promotion of FDI involves the coordination, commitment, and connections among many players across Canada in the FDI ecosystem. A number of stakeholders contribute to FDI promotion and facilitation in Canada at the federal, provincial, territorial and municipal levels. Investment promotion activities are critical to attracting FDI and to building and maintaining long-term relationships with investors.

Chapter 1: 2020 in review

1.1 Global economic performance

It's been over a decade since the 2008-2009 global financial crisis (GFC), and the global economy has once again suffered another recession, this time caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Since the onset of the pandemic, both advanced economies and emerging markets have struggled to balance virus containment measures against the negative impacts of such measures on their economies. In this first chapter of State of Trade 2021, we will look back at 2020 and the first 3 months of 2021 to examine how the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted the global economy.

Following 2019, a year marked by the slowest annual growth in world GDP since the GFC, the year 2020 began with an already elevated level of uncertainty due to trade disputes, geopolitical tensions, and social unrest. However, not long into the year, news of the spread of a viral disease became the centre of attention and added another layer of uncertainty. By the end of the first quarter, this initially localized health crisis had manifested into a global pandemic, becoming one of the greatest worldwide disasters in our lifetime.

While most countries did not implement COVID-19 restriction measures until mid-March 2020, COVID-19 had left a clear negative impact on most of the world's major economies by the end of the first quarter of 2020. Only one quarter into the year, world GDP had already declined by 12% (annualized)—the largest quarterly decline since comparable data was available. Besides mainland China suffering its first quarterly economic decline since 1992, all G7 economies recorded negative GDP growth over this period. The virus took a firm foothold in every corner of the world in the second quarter of 2020, forcing governments around the world to either extend or implement stricter COVID-19 containment measures. As a result, world GDP experienced a second contraction (‑ 24%, annualized). Fortunately, as the pandemic became more contained, and restrictions were gradually lifted, the global economy rebounded with historical growth in the third quarter of 2020 (+34%, annualized). Yet, recovery slowed down in Q4 to 6.6% (annualized) due to rising COVID-19 cases, prompting a second wave of lockdowns in many major economies. Moreover, despite 2 consecutive quarters of growth, global GDP in Q4 2020 remains 1.3% below the level recorded in the fourth quarter of the year prior.

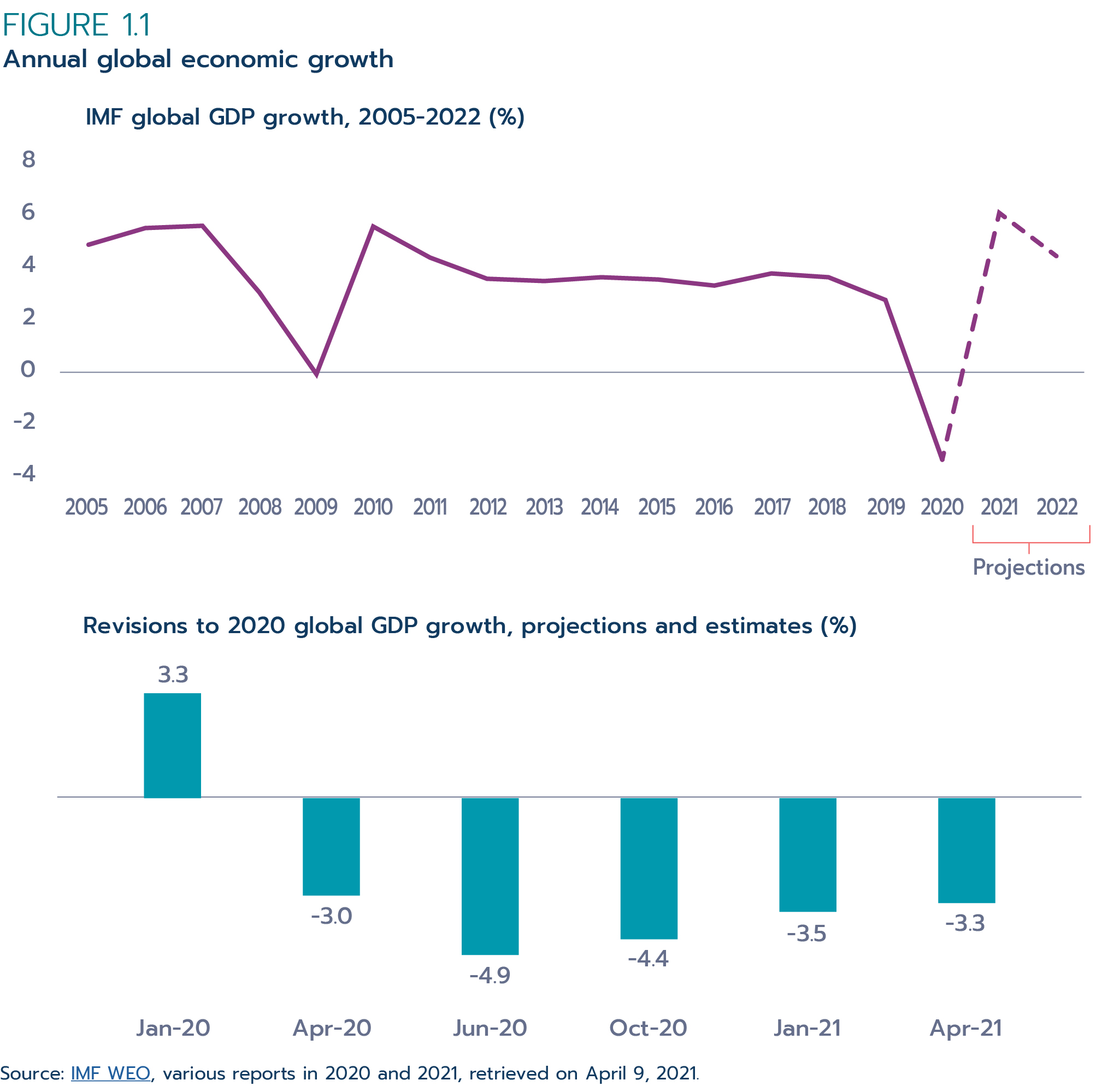

For the full year, bleak economic conditions and an unprecedented level of uncertainty were clearly visible in the economic data. For example, world GDP forecasts from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) were revised more often in 2020 and with more significant adjustments than in other years. Prior to the pandemic, the IMF forecasted in its January 2020 World Economic Outlook (WEO) that global GDP growth would accelerate in 2020, up 0.4 percentage points (pp) compared to 2019 to 3.3% (Figure 1.1). However, 3 months later in April, the pandemic had changed the world. Due to the costly but necessary government public health restrictions all around the world, the IMF significantly downgraded its 2020 forecast for world GDP growth to -3.0%. Since this forecast was made only a few months into the year, this baseline projection rested on many assumptions that were bound to change as the year unfolded. Indeed, 2 months later in June, the IMF once again drastically lowered its 2020 world GDP forecast, down 1.9 pp to ‑4.9%, mainly due to lengthier than expected lockdowns at the height of the pandemic. Estimates for 2020 then improved in the 2 subsequent releases, up 0.5 pp in October 2020 and another 0.9 pp in January 2021. In its April 2021 release, the IMF estimated world GDP to have contracted by 3.3% in 2020 and is forecasted to rebound by 6.0% in 2021 and 4.4% in 2022.

Text version

Figure 1.1 : Annual global economic growth

| 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021P | 2022P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4.9 | 5.4 | 5.5 | 3.0 | -0.1 | 5.4 | 4.3 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 3.6 | 3.5 | 3.3 | 3.8 | 3.6 | 2.8 | -3.3 | 6.0 | 4.4 |

Revisions to 2020 global GDP growth, projections and estimates (%)

| IMF WEO | 2020 |

|---|---|

| Jan-20 | -3.3 |

| Apr-20 | -3.0 |

| Jun-20 | -4.9 |

| Oct-20 | -4.4 |

| Jan-21 | -3.5 |

| Apr-21 | -3.3 |

Data source: IMF WEO, various reports in 2020 and 2021, retrieved on April 9, 2021.

A similar degree of uncertainty surrounded global trade. While a decline in international trade flows was inevitable due to COVID restrictions, the degree of deterioration depended on how governments balanced virus containment and lockdown with their economies. The adoption of various trade restrictive policies at the onset of the pandemic also contributed to the contraction in global trade. At the height of the first wave of the pandemic, due to the combined effect of widespread lockdowns, bans on international travel, and trade restrictions placed on critical supplies to combat the virus, the World Trade Organization (WTO) anticipated global merchandise trade volume would suffer a historical decline ranging from 13% to 32% for the full year (WTO, 2020a). But as the year unfolded with recovery in trade accelerating in the second half of the year, the WTO revised its forecast for 2020 upwards (WTO, 2021b). In its latest press release on March 31, 2021, the WTO indicated that global merchandise trade volume contracted by 5.3% in 2020—even better than the best-case scenario in its initial forecast back in April 2020 (WTO, 2021).

The global pandemic also introduced a multifaceted shock to global flows of foreign direct investment (FDI) leading to the largest annual decline in FDI on record. The immediate negative impacts are estimated to have dragged down global FDI flows by 42% in 2020 (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, 2020). But combined with its lingering effects, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) anticipates the COVID-19 pandemic to negatively impact the world's FDI flows in the long run far more than the GFC did. Moreover, the pandemic also had a varying degree of impact on FDI flows for different regions of the world. Developed countries were hit harder as their FDI flows fell by 69% in 2020, especially to Europe and the United States. In contrast, FDI flows to developing economies recorded a smaller decline of just 12%. Consequently, the share of global FDI in developing economies rose to 72% in 2020—the highest on record.

By the end of 2020, many countries had recovered, at least partially, from the pandemic. Collectively, we have avoided the worst-case scenario projected at the height of the pandemic, but the pace of recovery is still very much dictated by the direction in which the virus and its new variants are headed. Although the negative health and economic impacts from the pandemic are likely to remain in the medium term, as we gradually reach global herd immunity through vaccination, we can expect further cutbacks to restrictions and a return to our normal lives.

Box 1.1: The art of forecasting trade

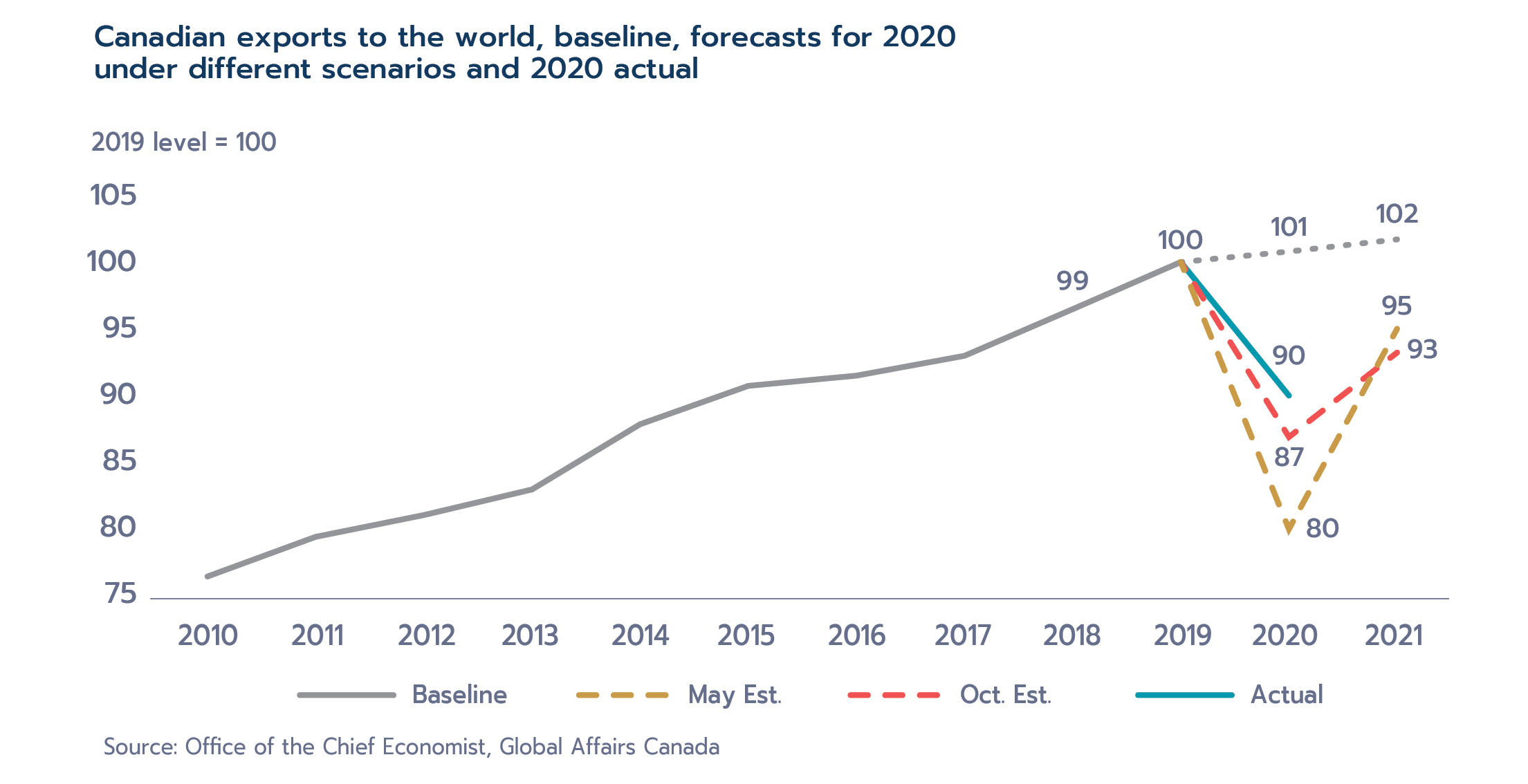

As COVID-19 rapidly spread and disrupted every aspect of our lives, many wanted to know how trade would be affected. To tackle this question, the Office of the Chief Economist (OCE) used an innovative approach to combine its Computable General Equilibrium (CGE) model with macroeconomic and sectoral growth projections from Oxford Economics (OE).

Instead of looking at the impact of a change in tariffs as a result of a free trade agreement, we examined the impact on Canadian trade of the adverse shocks on labour supply, the GDP shocks on the hardest-hit sectors (e.g. tourism, hospitality and air transport) due to social confinement, and the overall GDP shocks for all major economies. The forecast was first undertaken in May 2020 at the height of the first wave and then again in October 2020 to account for some of the recovery that was taking place.

In May 2020, OE expected that Canada's GDP would decline 11%, its labour supply would decrease 16%, and that the hardest-hit sectors would contract by 30-40%. Based on these shocks, the OCE's CGE model revealed that Canadian exports to the world would shrink by 20% in 2020 and grow by 17% in 2021. As the economy improved slightly, we reiterated the exercise in October 2020, with OE's revised GDP growth forecast of -5.3% in 2020, and 5.9% in 2021. Using these newest forecasts, OCE's CGE model indicated that Canada's exports to the world would decline by 13% in 2020, rather than by 20% as initially forecasted in May, followed by a recovery of 7.6% in 2021. The October forecast of -13% turned out to be 3 percentage points lower than the actual drop of 10% for 2020 as the economy continued to slowly recover in the last 3 months of 2020.

The CGE model also allows us to identify in which markets Canadian exports would decline the most. It suggests that exports to the U.K. (‑32%), the U.S. (‑13%), and Europe (‑13%) would be harder hit than to other countries due to the relatively more severe COVID-19 conditions in those regions, while our exports to China (‑5%) and South Korea (‑7%) would be the least affected.

Text version

Canadian exports to the world, baseline, forecasts for 2020 under different scenarios and 2020 actual

| 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 77 | 80 | 82 | 84 | 90 | 93 | 93 | 95 | 99 | 100 | 101 | 102 |

| May Est. | 100 | 80 | 95 | |||||||||

| Oct. Est. | 100 | 87 | 93 | |||||||||

| Actual | 100 | 90 |

Source: Office of the Chief Economist, Global Affairs Canada

1.2 Canadian economic performance

The recovery in Canada's economy mimicked the pattern for the global economy. Following implementation of COVID-19 restrictions in March 2020, the Canadian economy experienced some of its largest quarterly declines since comparable data were available in the first 2 quarters of the year, contracting by 7.9% in Q1 and another 38% in Q2 (annualized). However, as the first wave of the pandemic passed and restrictions were relaxed in Canada, a rapid recovery followed. The Canadian economy expanded by 42% in the third quarter (annualized), also the fastest quarterly expansion on record. The rebound in Canada's economic activities slowed down in the fourth quarter of 2020 to 9.3% (annualized), as rising cases led to a second phase of the outbreak prompting another wave of lockdowns targeted to regions affected.

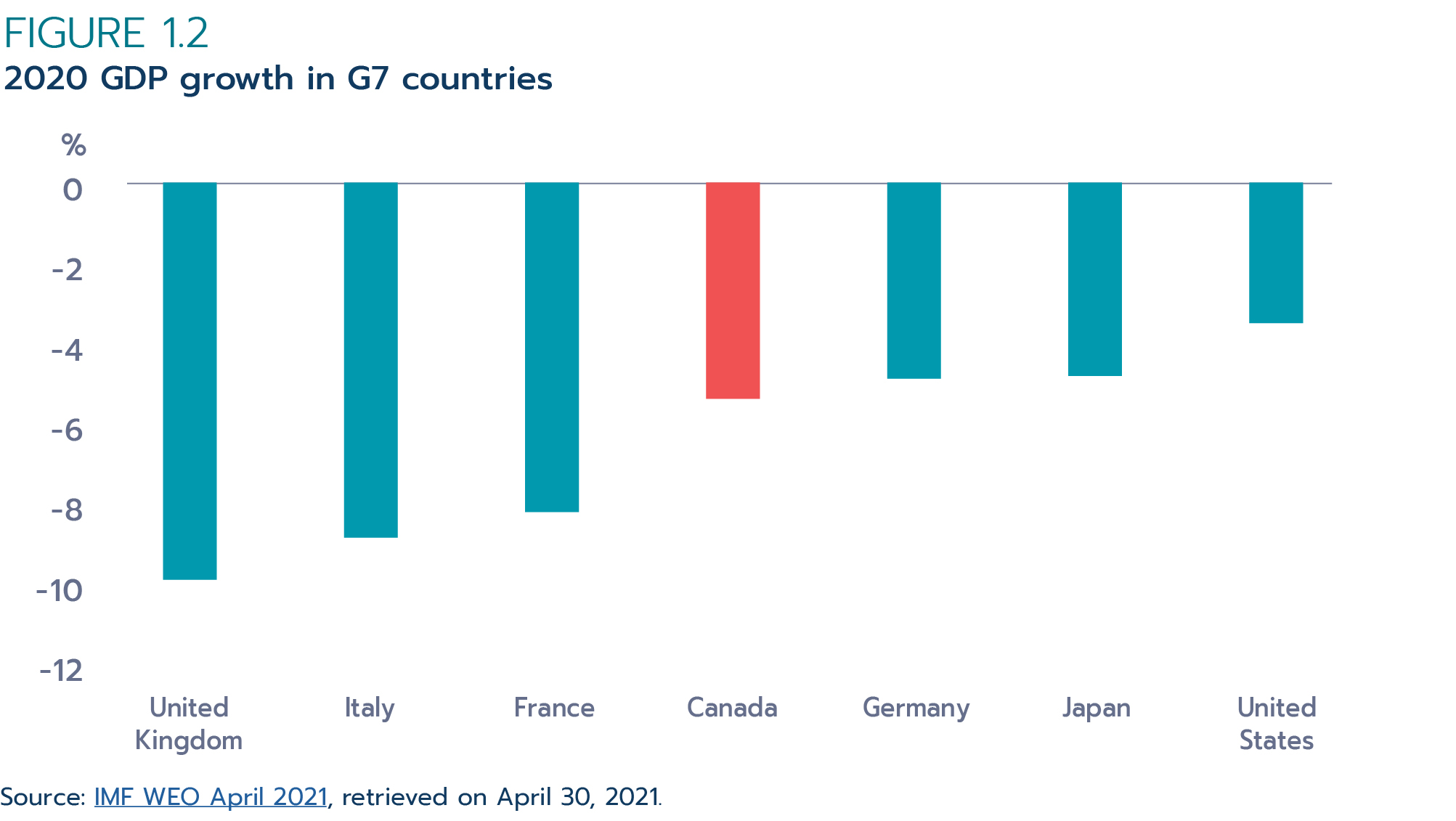

Overall, the Canadian economy contracted by 5.3% in 2020, the biggest contraction since comparable data were first recorded in 1961. Relative to other G7 countries, Canada stood in the middle of the pack in terms of decline in overall economic activities in 2020 (Figure 1.2).

Text version

Figure 1.2: 2020 GDP growth in G7 countries

| Country | 2020 |

|---|---|

| United Kingdom | -9.9% |

| Italy | -8.9% |

| France | -8.2% |

| Canada | -5.4% |

| Germany | -4.9% |

| Japan | -4.8% |

| United States | -3.5% |

Data source: IMF WEO April 2021, retrieved on April 30, 2021.

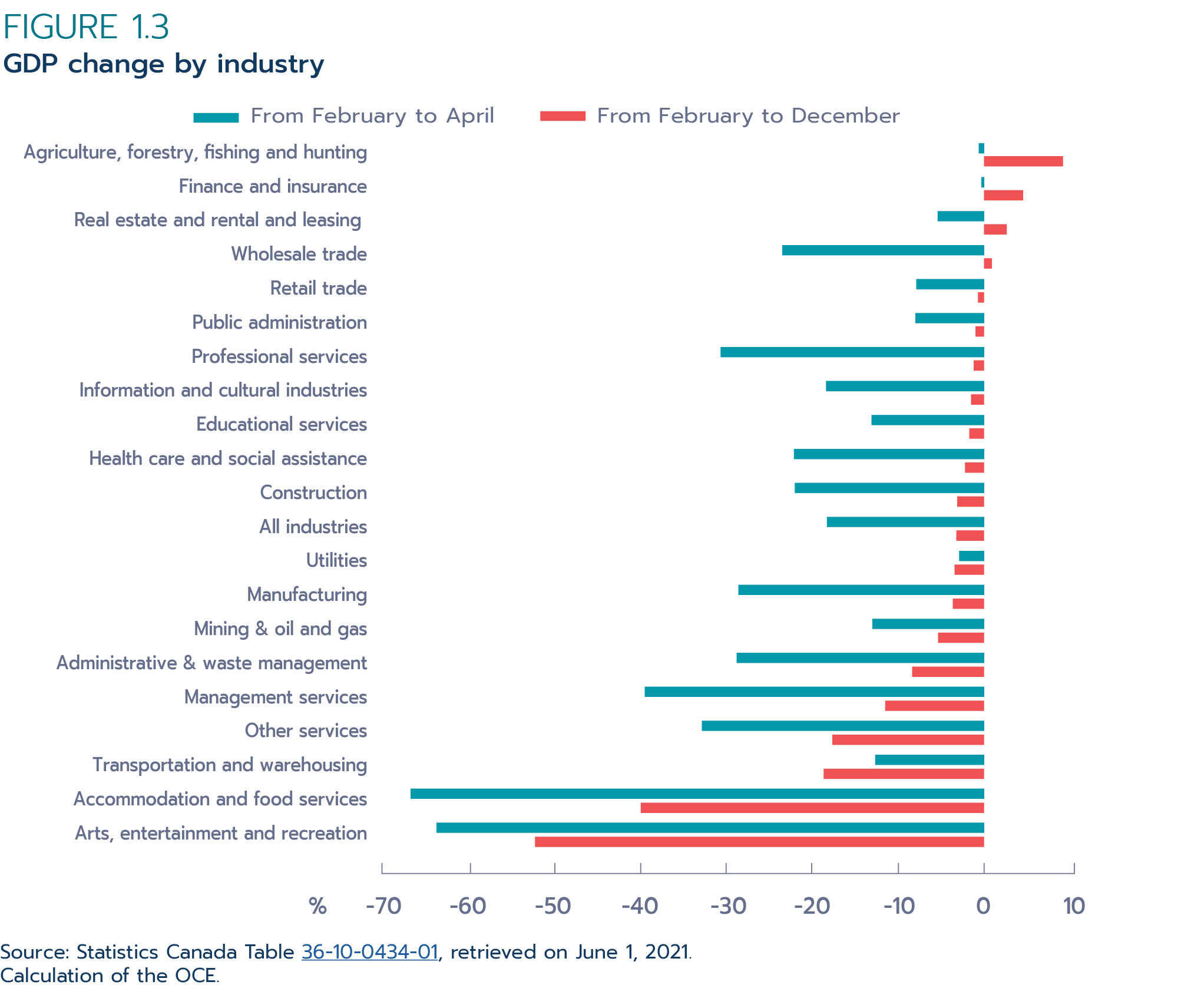

The pandemic had an uneven impact across sectors in Canada, resulting in a "K" shaped recovery that is characterized by certain sectors recovering early while others stagnate or continue to decline. After significant declines from factory closures and indoor gathering restrictions, the manufacturing sector was one of the first to bounce back as restrictions were lifted and consumers increased spending. Moreover, certain commercial services such as finance and insurance, and real estate and rental and leasing, showed exceptional resilience throughout the year. On the other hand, sectors that rely on social interactions were some of the most affected. Not only have sectors like accommodation and entertainment plummeted at the onset of the pandemic, but they continued to struggle as additional waves of lockdowns in high-risk zones led to further restrictions of their main business activities. It is unlikely that these sectors will fully recover before social distancing and containment measures are completely lifted. By the end of 2020, goods-producing sectors had recovered for the most part, while many services-producing sectors had yet to overcome pandemic challenges (Figure 1.3).

Text version

Figure 1.3: GDP change by industry

| Industry | From February to April (%) | From February to December (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Arts, entertainment and recreation | -61.3 | -51.8 |

| Accommodation and food services | -64.2 | -39.6 |

| Management services | -12.2 | -18.5 |

| Transportation and warehousing | -31.6 | -17.5 |

| Other services | -38.0 | -11.4 |

| Administrative & waste management | -27.7 | -8.3 |

| Mining & oil and gas | -12.5 | -5.3 |

| Manufacturing | -27.5 | -3.6 |

| Utilities | -2.8 | -3.4 |

| All industries | -17.6 | -3.2 |

| Construction | -21.2 | -3.1 |

| Health care and social assistance | -21.3 | -2.2 |

| Professional services | -12.6 | -1.7 |

| Educational services | -17.7 | -1.5 |

| Retail trade | -29.5 | -1.2 |

| Information and cultural industries | -7.7 | -1.0 |

| Public administration | -7.6 | -0.7 |

| Wholesale trade | -22.6 | 0.9 |

| Real estate and rental and leasing | -5.2 | 2.6 |

| Finance and insurance | -0.3 | 4.5 |

| Agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting | -0.6 | 9.1 |

Data source: Statistics Canada, Table 36-10-0104-01, retrieved June 1, 2021. Calculation of the OCE.

The pandemic also had a profound impact on the labour market. For the full year, overall Canadian employment declined by 5.2% or nearly 1 million jobs, leading to Canada's annual unemployment rate rising nearly 4 pp, from 5.7% in 2019 to 9.5% in 2020. The pandemic's immediate impact on the labour market far surpassed the one experienced during the aftermath of the 2008-2009 GFC. On a monthly basis, Canadian employment plummeted by nearly 16% in 2 months since losses started (February to April 2020). However, monthly employment figures rebounded strongly afterwards before plateauing in September 2020. By the end of the year (10 months after losses started), employment in Canada remained 3.4% below the level in February 2020. The brunt of the impact was again felt by high-contact service industries, especially accommodation and food services, which saw total industry employment decline by nearly 50% at the height of the pandemic and only half the lost jobs recovered by the end of the year.

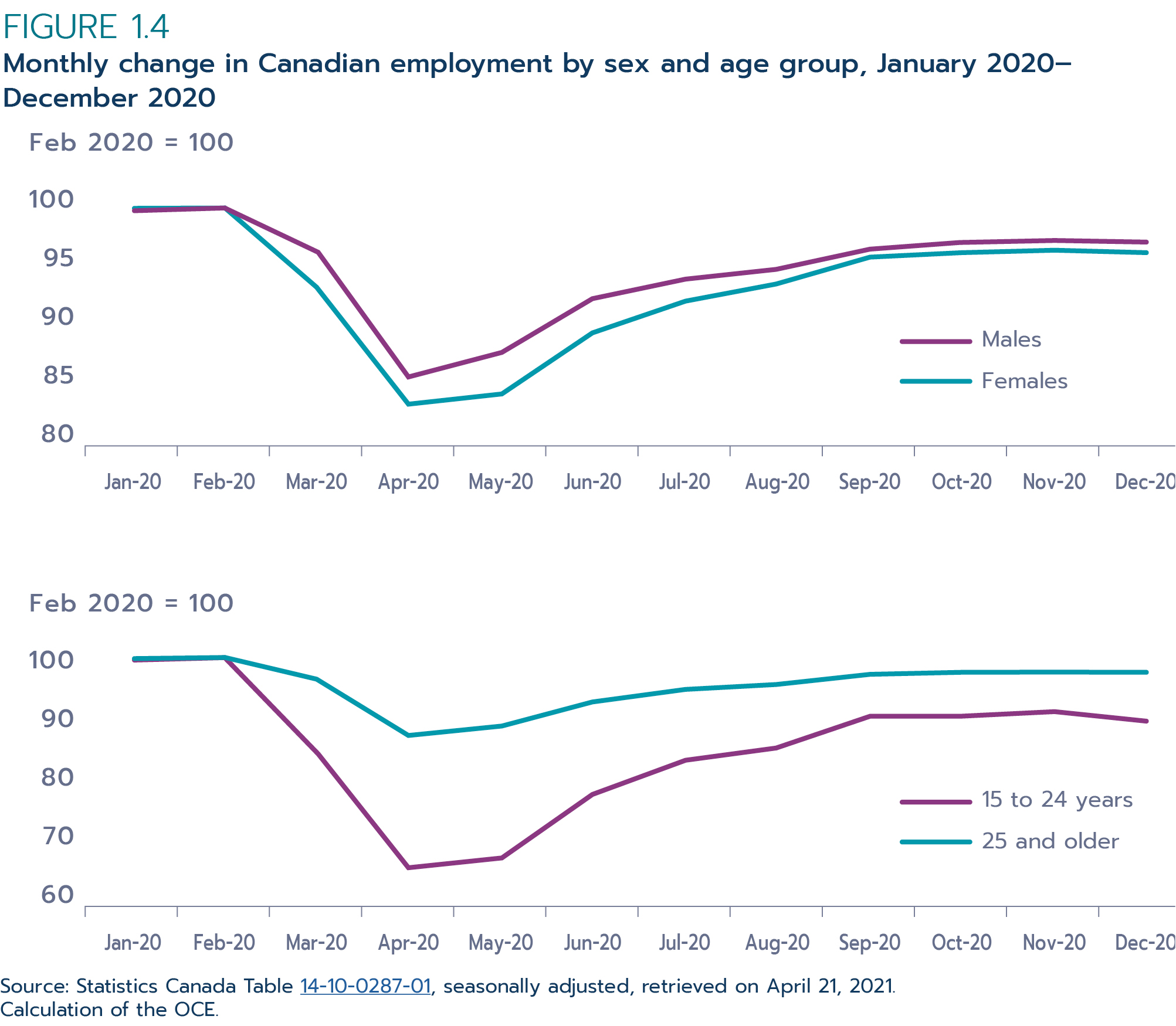

The gender and age gaps in employment were apparent early in the crisis. Female employment contracted by 17% compared to a 15% decline in male employment in the first 2 months since losses started. Similarly, employment in the 15-24 age group experienced a larger fall (-34%) than employment for all those aged 25 and older (‑13%). These gaps improved over the spring and summer, but have remained stable since.

Text version

Figure 1.4: Monthly change in Canadian employment by sex and age group, January 2020 ‑ December 2020

| Feb 2020 = 100 | Jan-20 | Feb-20 | Mar-20 | Apr-20 | May-20 | Jun-20 | Jul-20 | Aug-20 | Sep-20 | Oct-20 | Nov-20 | Dec-20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males | 99.8 | 100.0 | 96.3 | 85.4 | 87.6 | 92.3 | 94.0 | 94.7 | 96.4 | 97.0 | 97.3 | 97.1 |

| Females | 100.0 | 100.0 | 93.1 | 83.2 | 84.2 | 89.3 | 92.1 | 93.6 | 95.8 | 96.2 | 96.5 | 96.1 |

| Feb 2020 = 100 | Jan-20 | Feb-20 | Mar-20 | Apr-20 | May-20 | Jun-20 | Jul-20 | Aug-20 | Sep-20 | Oct-20 | Nov-20 | Dec-20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 to 24 years | 99.5 | 100.0 | 84.0 | 65.7 | 67.5 | 77.6 | 83.1 | 85.4 | 90.4 | 90.5 | 91.2 | 89.6 |

| 25 and older | 99.9 | 100.0 | 96.5 | 87.3 | 88.9 | 93.0 | 94.6 | 95.6 | 97.0 | 97.6 | 97.8 | 97.7 |

Data source: Statistics Canada Table 14-10-0287-01, seasonally adjusted, retrieved on April 21, 2021. Calculation of the OCE.

1.3 Canadian trade performanceFootnote 1

Like much of the world, Canada's international trade was affected by the global pandemic in 2020. Year-over-year, Canada's total trade in goods and services collapsed by 13% to $1.3 trillion in value. This was the second-fastest 1-year decline on record, after the 17% contraction observed from 2008 to 2009 from the GFC (Figure 1.5). Both Canadian exports and imports recorded double-digit declines, down 13% and 12%, respectively. As the decline in exports was greater than that of imports, Canada's trade deficit widened by $8.4billion in value to $45 billion. Moreover, as international trade was especially impacted by COVID restrictions, Canada's trade-to-GDP ratio plummeted more than 5 pp, from 65% in 2019 to 60% in 2020—also the lowest since 2009.

Text version

Figure 1.5: Canadian trade in goods and services and trade-to-GDP ratio, 2005 ‑ 2020

| Import ($M) | Export ($M) | Trade to GDP (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 467,732 | 523,945 | 70 |

| 2006 | 488,627 | 529,824 | 68 |

| 2007 | 505,701 | 540,026 | 66 |

| 2008 | 540,669 | 569,939 | 67 |

| 2009 | 470,749 | 448,079 | 58 |

| 2010 | 517,153 | 485,942 | 60 |

| 2011 | 564,513 | 544,254 | 62 |

| 2012 | 589,137 | 554,612 | 63 |

| 2013 | 606,801 | 576,989 | 62 |

| 2014 | 651,176 | 633,112 | 64 |

| 2015 | 683,019 | 633,955 | 66 |

| 2016 | 685,868 | 638,095 | 65 |

| 2017 | 720,254 | 673,326 | 65 |

| 2018 | 763,874 | 721,679 | 67 |

| 2019 | 774,372 | 737,500 | 65 |

| 2020 | 683,685 | 638,449 | 60 |

Data source: Statistics Canada, Table 36-10-0104-01, retrieved June 1, 2021. Calculation of the OCE.

Goods

In 2020, overall Canadian trade in goods contracted by 10% compared to 2019. Canadian goods exports were more affected than imports, falling by 12% to $524 billion in value, while goods imports only contracted by 8.5% to $561 billion. The sharp fall in goods exports was a result of a combination of both the price and the volume effect. Year-over-year, goods export volumes fell 6.6%, and export prices were down 6.1%. On the other hand, the contraction for Canadian goods imports was driven purely by volume, down 9.7%, while import prices rose 1.3% compared to the previous year.

Trade performance by product sector

The declines in exports were concentrated in the second quarter of the year, when pandemic-restriction measures were implemented at home and abroad, limiting social interactions and halting factory productions. Most export sectors posted declines during the first wave of the pandemic, with those producing durable goods and relying on international supply chains being the most affected. However, similar to global trade, export sectors in Canada rebounded in the second half of the year. By the end of December, the level of Canadian goods exports was only 0.6% lower when compared to the pre-COVID benchmark in February. For 2020 overall, 8 out 11 goods export sectors posted declines.

In 2020, the top 3 Canadian goods exports in terms of value were energy products, motor vehicles and parts, and consumer goods (Table 1.1), the same as it was in 2019. However, the 2 largest export sectors, energy and motor vehicles, registered historical declines and were responsible for most of the decline in total Canadian goods exports, while exports of consumer goods improved marginally. As a result, the top 3 sectors together only accounted for 42% of Canada's goods exports, down 5 pp from 47% in 2019.

Energy products remain the top export sector for Canada, accounting for 14% of Canada's total exports. Nonetheless, the sector posted its fastest 1-year decline in export value on record and the largest contraction in value out of all the sectors in 2020. Compared to 2019, the sector shrank by 37% or $43 billion to $74 billion, a decline mainly attributable to the $34-billion drop in exports of crude oil and crude bitumen. Additionally, other energy products such as refined petroleum and coal also recorded annual declines of over 40%. Partially mitigating these declines were higher exports of electricity (+2.1%) and nuclear fuel and other energy products (+15%). Exports in this sector have rebounded since the initial shock from the pandemic with overall energy exports in December 2020 only 3.4% below the level in February.

Motor vehicles and parts was Canada's second-largest export sector in 2020. Following strong growth in 2019, exports of motor vehicles and parts declined 20% in 2020, mainly due to lower exports of passenger cars and light trucks. Like energy products, the declines in exports of motor vehicles and parts were also concentrated during the initial wave of the pandemic, falling as much as 85% from February to April. However, while exports rebounded rapidly in the third quarter as restrictions were lifted, recovery plateaued in the fourth quarter of 2020. By the end of the year, exports of motor vehicles and parts stood at 8.8% below its pre-pandemic level.

In addition to energy and motor vehicles and parts, 6 other product sectors posted declines in export value in 2020. Four recorded double-digit declines: industrial machinery, equipment and parts; basic and industrial chemical, plastic and rubber products; electronic and electrical equipment and parts; and aircraft and other transportation equipment and parts. It should be noted that the annual results mask the important movement from month to month in exports in 2020. Exports declined dramatically in April and May due the spread of COVID-19 and slowly recovered in the following months. By late 2020, most export sectors had returned to pre-COVID levels.

On the import side, 7 out of 11 sectors posted declines for the full year. Consumer goods remain the top import sector, accounting for over one fifth of Canadian imports. The sector recorded a moderate expansion of 1.4%, primarily because of increased imports of medical supplies and personal protective equipment to combat the pandemic. The other 3 sectors that posted increases in imports were metal and non-metallic mineral products; metal ores and non-metallic minerals; and farm, fishing and intermediate food products. In contrast, large import sectors such as motor vehicles and parts and industrial machinery, equipment and parts recorded substantial declines.

Table 1.1: Value of Canadian goods trade in 2020 by product sector

Value | Change | Change | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exports | |||

| Aircraft and other transportation equipment and parts | 22 | -20 | -5.6 |

| Basic and industrial chemical, plastic and rubber products | 31 | -11 | -3.7 |

| Consumer goods | 71 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Electronic and electrical equipment and parts | 26 | -12 | -3.6 |

| Energy products | 74 | -37 | -43 |

| Farm, fishing and intermediate food products | 44 | 15 | 5.7 |

| Forestry products and building and packaging materials | 42 | -0.6 | -0.3 |

| Industrial machinery, equipment and parts | 35 | -15 | -6.0 |

| Metal and non-metallic mineral products | 67 | 2.5 | 1.6 |

| Metal ores and non-metallic minerals | 21 | -0.2 | 0.0 |

| Motor vehicles and parts | 74 | -20 | -19 |

| Total | 524 | -12 | -74 |

| Imports | |||

| Aircraft and other transportation equipment and parts | 19 | -27 | -7.0 |

| Basic and industrial chemical, plastic and rubber products | 41 | -8.3 | -3.8 |

| Consumer goods | 127 | 1.4 | 1.8 |

| Electronic and electrical equipment and parts | 68 | -5.8 | -4.2 |

| Energy products | 23 | -39 | -14 |

| Farm, fishing and intermediate food products | 21 | 0.8 | 0.2 |

| Forestry products and building and packaging materials | 26 | -3.3 | -0.9 |

| Industrial machinery, equipment and parts | 60 | -13 | -8.9 |

| Metal and non-metallic mineral products | 50 | 26 | 10 |

| Metal ores and non-metallic minerals | 16 | 16 | 2.3 |

| Motor vehicles and parts | 87 | -24 | -28 |

| Total | 561 | -8.5 | -52 |

Data source: Statistics Canada, Table 12-10-0122-01, retrieved May 31, 2021. Calculation of the OCE.

Box 1.2: Are immigrant-led SMEs more likely to export?

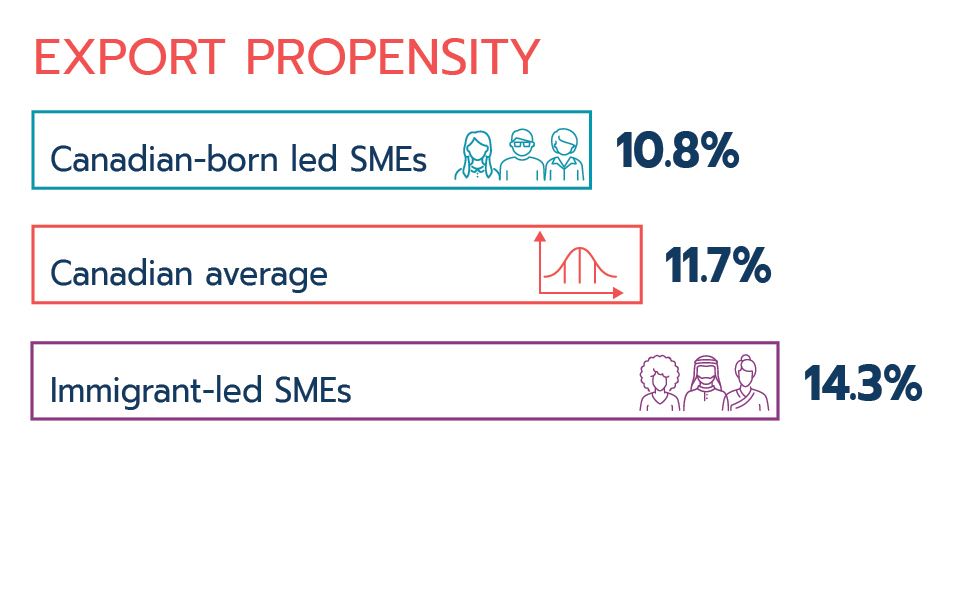

Canada has a large immigrant population: 1 in 5 Canadians are foreign born. New Canadians are typically highly educated: 34% have a bachelor's degree. As observed in many countries, immigrants are more likely to own or run a business than are native-born citizens. In Canada, immigrant-led small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs)* are more likely to export (14.3%), compared to both the Canadian average (11.7%) and SMEs with Canadian-born leaders (10.8%) (Blanchet, 2021).

Data source: Statistics Canada, Survey on financing and growth of small and medium enterprises, 2017.

Calculation of the OCE.

A number of factors may help explain this phenomenon. Immigrants continue to maintain relationships with, and have intrinsic knowledge of how to conduct business in, their countries of origin: this facilitates exporting to their home countries. It is also observed that immigrant-led SMEs are more likely to operate in export-intensive industries, such as accommodation and food services, or retail trade. In addition, between 2014 and 2017, the number of immigrant-led SMEs grew proportionally faster than the number of SMEs led by those born in Canada: immigrants in Canada currently lead 1 in 4 SMEs. Furthermore, the number of immigrant-led SMEs that export has grown almost twice as fast (+27%) as the number of exporting SMEs led by those born in Canada (+14%).

Considering women-owned SMEs in Canada, the export propensity of SMEs owned by immigrant women is almost twice that of those owned by Canadian-born women, at 17% and 9.0%, respectively. In short, the contribution of immigrants to Canada's economy and trade performance is undeniable.

* The immigrant-led SME category refers to SMEs where the primary decision maker self-identifies as being born outside of Canada.

Text version

Export propensity

| Export propensity (%) | |

|---|---|

| Canadian-born led SMEs | 10.8 |

| Canadian average | 11.7 |

| Immigrant-led SMEs | 14.3 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Survey on financing and growth of small and medium enterprises, 2017. Calculation of the OCE.

Goods import sources and export destinations

Canada's goods exports declined to most of its top trading partners in 2020. Although the United States remains Canada's top export destination by far, Canadian goods exports to the U.S. plummeted by 16% for the year. As this decline outpaced the overall decline in Canadian goods exports, the U.S. share of Canadian goods exports contracted to 72% in 2020—the lowest since 1982. At the same time, Canadian goods imports from the U.S. also registered a double-digit decline of 11%. Overall, lower 2-way trade with the U.S. accounted for most of the decline in Canada's goods trade in 2020.

In comparison, exports to the European Union (EU) and the United Kingdom (U.K.) have held up relatively well. Year-over-year, Canadian exports to the EU fell 2.0% and imports from the EU fell 12%. Moving into the third year of Canada-European Union Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA), Canadian exports to the EU remain strong despite the pandemic. Of the main EU partners, exports rose significantly to Italy and the Netherlands. Although the U.K. left the EU at the beginning of the year, the temporary measures put in place during this transitional period maintained the status quo and continue to facilitate 2-way trade between Canada and the U.K. For 2020 overall, both Canadian exports to and imports from the U.K. improved, advancing by 4.4% and 12%, respectively.

Trade with partners in Asia showed a mixed picture. Following the largest decline on record in 2019, Canadian goods exports to China advanced 7.4% in 2020, supported by farm, fishing and intermediate food products; metal ores and non-metallic minerals; and consumer goods. Meanwhile, Canadian goods imports from China climbed 5.7% on the back of increased shipments of consumer goods. Trade with other large Asian trading partners recorded different levels of declines. Exports to Japan held up relatively well (‑2.2%), but exports to South Korea, India, and Hong Kong all recorded historical declines.

Table 1.2: Value of Canadian goods trade in 2020 by partner

Value | Change | Change | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exports | |||

| United States | 376 | -16 | -70 |

| European Union | 29 | -2.0 | -0.6 |

| China | 26 | 7.4 | 1.8 |

| United Kingdom | 21 | 4.4 | 0.9 |

| Japan | 13 | -2.2 | -0.3 |

| Mexico | 7.0 | -16 | -1.4 |

| South Korea | 4.8 | -16 | -0.9 |

| India | 3.8 | -24 | -1.2 |

| Hong Kong | 1.9 | -53 | -2.2 |

| Other Countries | 41 | -0.1 | 0.0 |

| Total | 524 | -12 | -74 |

| Imports | |||

| United States | 349 | -11 | -43 |

| European Union | 51 | -12 | -6.9 |

| China | 50 | 5.7 | 2.7 |

| Mexico | 17 | -17 | -3.5 |

| Japan | 10 | -19 | -2.4 |

| United Kingdom | 9.4 | 12 | 1.0 |

| South Korea | 7.5 | -10 | -0.8 |

| Hong Kong | 4.2 | -0.7 | 0.0 |

| India | 3.9 | -5.9 | -0.2 |

| Other Countries | 60 | 1.1 | 0.6 |

| Total | 561 | -8.5 | -52 |

Data source: Statistics Canada, Table 36-10-0023-01, retrieved May 31, 2021. Calculation of the OCE.

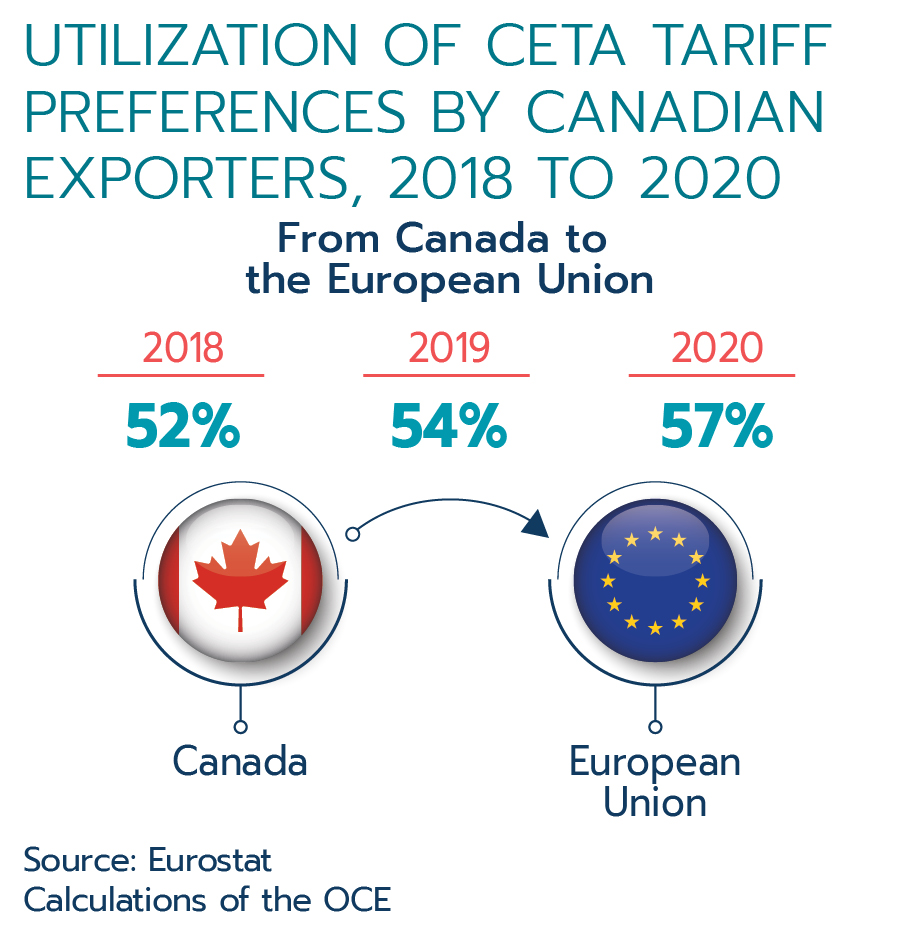

Box 1.3: Promoting FTAs: helping more Canadian exporters understand how to use them

Some Canadian exporters are still unaware of the benefits of free trade agreements (FTAs) and the resources at their disposal to make full use of them.* In the last few years, Global Affairs Canada (GAC) has taken an innovative approach to help as many exporters as possible understand and fully utilize such FTAs as the Canada-United States-Mexico Agreement (CUSMA), the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), and the Canada-European Union Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA).

To that end, GAC has been busy honing its innovative strategies, adding the following business intelligence tools to its toolkit:

- Canada Tariff Finder, which allows a potential exporter to search the tariffs applicable to its product (using harmonized system codes) in an FTA partner country

- Market Potential Finder, which enables trade commissioners to determine market opportunity leads for exporting businesses in CETA countries and in selected CPTPP economies based on intelligence developed from empirical trade data and exclusive qualitative input from the Trade Commissioner Service (TCS) network abroad

In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted international business conditions, which created additional challenges for businesses wanting to export. Once again, GAC innovated by transitioning from in-person training sessions to digital offerings. In the fall of 2020, GAC held the first virtual trade mission (VTM) to South Korea. Led by the Honourable Mary Ng, Minister of Small Business, Export Promotion and International Trade, the VTM highlighted the tools, programs, business leads and information the TCS and its partners can offer Canadian entrepreneurs and exporters looking to expand in South Korea. It also provided information about sectors of growth in South Korea, available export support and funding, as well as the benefits of FTAs such as the Canada-Korea Free Trade Agreement (CKFTA). The VTM was a huge success; it allowed micro-firms and underrepresented exporters that might otherwise have lacked the time or money to participate in a regular trade mission to join virtually. The benefits of using a hybrid virtual/in-person approach for future trade missions are clear.

Recent data on utilization of FTAs have shown GAC the importance of continuing its FTA promotion activities. After CUSMA replaced the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and entered into force on July 1, 2020, the agreement maintained a high utilization rate in the second half of 2020: 69% of Canadian exporters to the U.S. leveraged the trade benefits of the agreement. In contrast, CETA has only been in force for 3 years, and the FTA promotion activities have been crucial to increase awareness among exporters. The utilization of CETA among Canadian exporters to the EU-27 improved noticeably, from about 52% in 2018 to about 57% in 2020. Further work will be required to increase CETA utilization rates to levels comparable to those of CUSMA. The TCS is looking to engage businesses in more sector-specific activities and assist them in their strategic plans to diversify their export markets.

*Global Affairs Canada's survey (n=2,089) on "Canadian Attitudes towards International Trade" conducted in February 2020 suggests that while Canadians are generally supportive of free trade, they have limited knowledge of free trade agreements.

Text version

Utilization of CETA tariff preferences by Canadian exporters, 2018 to 2020

| Utilization rate (%) | |

|---|---|

| 2018 | 52 |

| 2019 | 54 |

| 2020 | 57 |

Source: Eurostat.

Calculation of the OCE.

Box 1.4: TCS leveraged its expertise to secure critical medical supplies for Canadians

In 2020, Canada dramatically increased its imports of medical supplies in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Overall Canadian imports of medical supplies grew by 30% year-over-year, led by 137% growth in personal protective equipment (PPE). The United States remained Canada's top source of imports. The U.S. in harnessing its advanced medical resources was Canada's main supplier of sophisticated medical products such as medical devices, diagnostic instruments, and medicaments. China followed closely in second place, supplying over 60% of Canada's PPE imports over the past year. Since the start of the pandemic, Canada was also able to import more medical goods from other trading partners in Europe, such as Switzerland and Sweden, and in Asia, most notably South Korea and Malaysia. However, monthly Canadian imports of medical goods (especially PPE) have trended down since peaking in June 2020, likely a result of the government's "Made in Canada" call to action, which supported building domestic PPE production capacity. By February 2021, imports were at their lowest monthly value since March 2020.

Since the start of the pandemic, the TCS has played a pivotal role in securing critical medical supplies. At the height of the pandemic when Canada faced an unprecedented demand for PPE and medical devices such as ventilators, the TCS leveraged its expertise to identify likely sellers of PPE and brokered the best deals on behalf of Canada. As medical goods shortages were eventually resolved, the TCS then worked tirelessly to ensure an adequate supply of COVID-19 vaccines reached Canadians. At the same time, despite pandemic challenges, the TCS continued to support Canadian exporters by connecting businesses to customers abroad.

Services

The global pandemic had an even larger impact on services trade, especially on sectors that depend on face-to-face interactions. For the full year, Canadian services trade fell by 21% to $237 billion in value, with services exports declining by 18% and services imports plummeting 24%.

Services trade by sector

As pandemic containment measures around the world restricted travel and kept a large portion of the global population housebound, travel and transportation became the 2 hardest-hit sectors. In 2020, Canadian travel exports plummeted 59%, and travel imports fell 66% compared to the year prior, mainly because countries imposed restrictions on entry into their territory and fewer individuals travelled. Similarly, Canadian exports of transportation services were down 27% over this period, and transportation imports fell 28%, with air transportation contributing the most to the declines since air transportation is more dependent on passenger travels. By the end of December 2020, on a seasonally adjusted basis, both travel and transportation exports were still well below their pre-pandemic levels in February 2020. Industry experts predict that levels would not return to normal in the short term.

In a sharp contrast to travel and transportation services, trade in commercial services has held steady throughout the year and even surpassed pre-COVID levels. On a year-over-year basis, Canadian exports of commercial services advanced 3.2% to $84 billion in value. This growth was mainly supported by increased exports of professional and management consulting services, and financial services. At the same time, Canadian imports of commercial services were up 2.5% to reach $81 billion, with increased imports of financial services partially offset by lower imports of maintenance and repair services.

Table 1.3: Value of Canadian services trade in 2020 by type

Value | Change | Change | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exports | |||

| Commercial | 84 | 3.2 | 2.6 |

| Travel | 15 | -59 | -22 |

| Transportation | 14 | -27 | -4.9 |

| Government | 1.4 | -17 | -0.3 |

| Total | 115 | -18 | -25 |

| Imports | |||

| Commercial | 81 | 2.5 | 1.9 |

| Transportation | 16 | -66 | -31 |

| Travel | 23 | -28 | -9.1 |

| Government | 1.4 | -8.0 | -0.1 |

| Total | 122 | -24 | -39 |

Data source: Statistics Canada, Table 36-10-0021-01, retrieved May 31, 2021. Calculation of the OCE.

Services import sources and export destinations

Canada posted double-digit declines in services trade with every one of its top trading partners in 2020. As the United States is Canada's largest services trading partner by far, it accounted for most of this contraction in terms of value. Year-over-year, Canadian services exports to the United States fell by 12% or $8.9 billion, almost entirely driven by the 85% decline in travel exports and 16% decline in transportation exports, while exports of commercial services were up 5.7%. At the same time, services imports from the U.S. contracted 22% or $19 billion, with travel and transportation imports declining by 69% and 37%, respectively.

Services trade with partners in Europe and Asia showed a similar decline. Although the EU remained Canada's second-largest services trading partner, 2-way trade in every type of service declined in 2020. For the full year, services exports to the EU fell by 28%, while services imports fell 30%. The United Kingdom, no longer part of the EU, stood as the third-largest services trading partner for Canada, followed by China and Hong Kong to round out the top 5. Services trade with all 3 partners deteriorated in 2020.

Table 1.4: Value of Canadian services trade in 2020 by trade partner

Value | Change | Change | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exports | |||

| United States | 66 | -12 | -8.9 |

| European Union | 11 | -28 | -4.5 |

| United Kingdom | 5.8 | -20 | -1.5 |

| China | 5.4 | -34 | -2.7 |

| India | 2.8 | -32 | -1.4 |

| Hong Kong | 1.4 | -26 | -0.5 |

| Japan | 1.3 | -33 | -0.6 |

| Mexico | 1.2 | -40 | -0.8 |

| South Korea | 0.8 | -38 | -0.5 |

| Other Countries | 19 | -15 | -3.4 |

| Total | 115 | -18 | -25 |

| Imports | |||

| United States | 68 | -22 | -19 |

| European Union | 14 | -30 | -6.2 |

| United Kingdom | 7.0 | -11 | -0.8 |

| Hong Kong | 4.5 | -16 | -0.8 |

| China | 2.4 | -29 | -1.0 |

| Mexico | 2.2 | -49 | -2.1 |

| Japan | 2.1 | -31 | -1.0 |

| India | 2.0 | -18 | -0.5 |

| South Korea | 0.4 | -20 | -0.1 |

| Other Countries | 19 | -27 | -7.1 |

| Total | 122 | -24 | -39 |

Data source: Statistics Canada, Table 36-10-0024-01, may 31, 2021 . Calculation of the OCE.

1.4 Canadian foreign direct investment performance

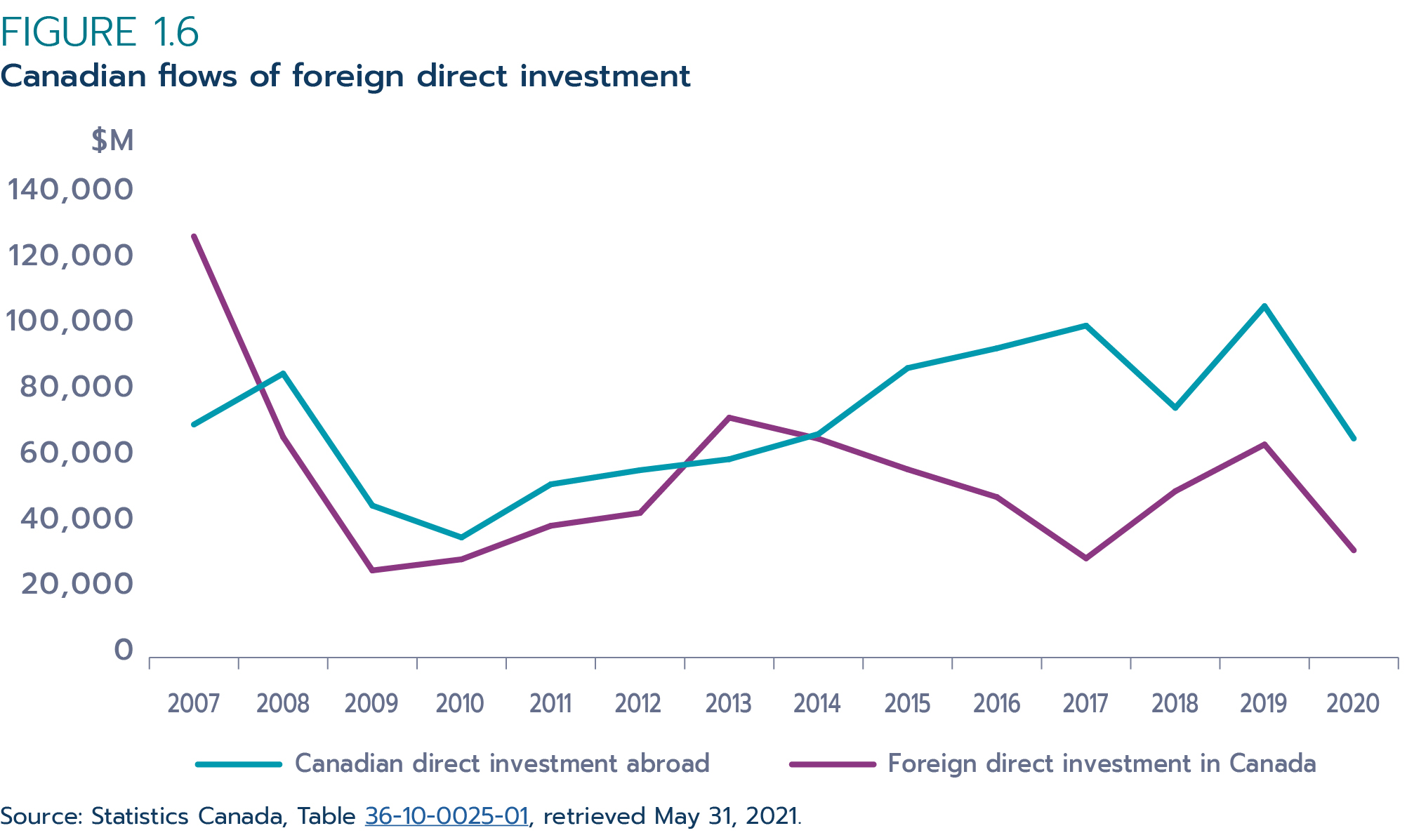

Like other aspects of the economy, Canada's foreign investment performanceFootnote 2 was severely impacted by the global pandemic, with both flows of inward foreign direct investment (FDI) and Canadian direct investment abroad (CDIA) registering large declines. For 2020 overall, Canadian FDI flows plummeted by 49% or $31 billion, and CDIA contracted 41% or $42 billion. While foreign direct investment flows have historically been more volatile than trade or other aspects of the economy, this level of 1‑year decline was only surpassed by the crashes in FDI and CDIA due to the GFC in 2008-2009 when they fell by 60% and 46%, respectively. Nevertheless, the decline in Canada's foreign direct investment performance was roughly on par with that of the world.

Text version

Figure 1.6: Canadian flows of foreign direct investment

$ Millions

| Canadian direct investment abroad | Foreign direct investment in Canada | |

|---|---|---|

| 2007 | 69,416 | 125,476 |

| 2008 | 84,592 | 65,679 |

| 2009 | 45,268 | 25,948 |

| 2010 | 35,770 | 29,257 |

| 2011 | 51,602 | 39,254 |

| 2012 | 55,819 | 43,076 |

| 2013 | 59,091 | 71,459 |

| 2014 | 66,584 | 65,186 |

| 2015 | 86,242 | 56,057 |

| 2016 | 92,140 | 47,796 |

| 2017 | 98,888 | 29,550 |

| 2018 | 74,402 | 49,552 |

| 2019 | 104,681 | 63,470 |

| 2020 | 62,276 | 32,321 |

Data source: Statistics Canada, Table 36-10-0025-01, retrieved May 31, 2021.

Box 1.5: Canada's FDI recovery following the GFC suggests post-COVID recovery

Contribution by Invest in Canada

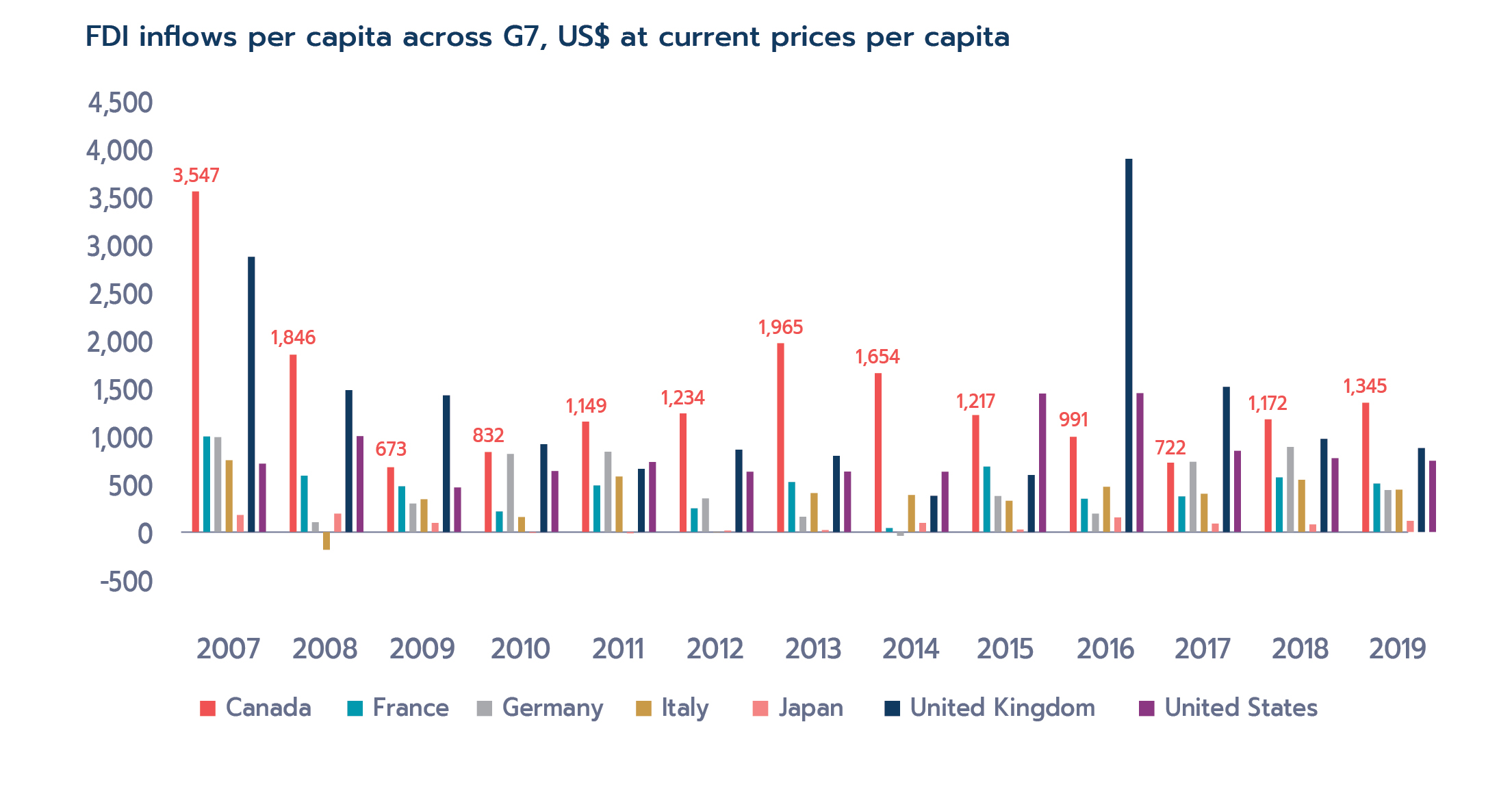

As seen in Figure 1.6, Canada's FDI flows took a hit in 2020. This 49% drop was relatively less severe than the decline caused by the GFC when FDI flows fell by over 60%, from $66 billion to $26 billion between 2008 and 2009 (Statistics Canada, Table 36-10-0025-01). Flows started recovering in 2010, but it took 4 years before they surpassed their 2008 pre-GFC level. While Canada's recovery may appear to be slow, Canada's FDI performance in past crises demonstrates Canada's resilience and stability in comparison to its G7 peers. Based on UNCTAD data, Canada was the only G7 country to demonstrate 9 years of consecutive growth in FDI inflows following the recession in the early 1990s and was also the only G7 country to demonstrate 4 years of consecutive growth in FDI inflows following the GFC. The later growth led to Canada increasing its 1.8% share of global FDI flows in 2009 to 4.8% by 2013, the largest gain in global FDI share than any other G7 country—ahead of the U.S. whose share increased 2.2 pp. During the same period, Canada also had the highest FDI flows per capita (US$1,965.3) among the G7 by 2013. Canada's past performance showed that, although it may take a few years, Canada's FDI flows do rebound from a large shock and hopefully they will likewise rebound from the COVID-19 pandemic in the not-too-distant future.

Text version

FDI inflows per capita across G7, US$ at current prices per capita

| 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canada | 3,547 | 1,846 | 673 | 832 | 1,149 | 1,234 | 1,965 | 1,654 | 1,217 | 991 | 722 | 1,172 | 1,345 |

| France | 993 | 585 | 476 | 214 | 484 | 244 | 519 | 40 | 681 | 345 | 370 | 568 | 504 |

| Germany | 987 | 100 | 294 | 812 | 835 | 348 | 157 | -39 | 373 | 190 | 730 | 885 | 435 |

| Italy | 746 | -184 | 340 | 155 | 576 | 2 | 404 | 385 | 324 | 469 | 396 | 542 | 439 |

| Japan | 175 | 190 | 93 | -10 | -14 | 13 | 18 | 94 | 23 | 152 | 86 | 77 | 115 |

| United Kingdom | 2,866 | 1,477 | 1,422 | 914 | 657 | 856 | 792 | 376 | 593 | 3,887 | 1,512 | 969 | 872 |

| United States | 710 | 997 | 463 | 633 | 729 | 627 | 629 | 626 | 1,442 | 1,445 | 844 | 768 | 741 |

Source: UNCTADStat, retrieved April 22, 2021.

FDI and CDIA sectoral composition

By sector, most of the $42-billion decrease in CDIA flows in 2020 can be attributed to the management of companies and enterprises sector (a notable $27-billion or 78% decrease following a spike in the year prior), trailed by energy and mining, and trade and transportation. In contrast, CDIA flows in the finance and insurance sector contracted marginally, and those in the manufacturing sectors and "Other industries" expanded .

On the other hand, energy and mining was the main driver of the decline in FDI flows. Following a $15‑billion increase in 2019 to over $20 billion in value, FDI in this sector posted a huge contraction in 2020, resulting in divestment of $7.3 billion. FDI flows into Canada's finance and insurance, management of companies and enterprises, and manufacturing sectors also recorded significant declines.

Table 1.5 Canada's CDIA and FDI flows by sector (2020)

Value | Change | Change | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CDIA | |||

| Energy and mining | 5.3 | -70 | -12 |

| Finance and insurance | 29 | -2.0 | -0.6 |

| Management of companies and enterprises | 7.4 | -78 | -27 |

| Manufacturing | 5.1 | 5.8 | 0.3 |

| Trade and transportation | 1.6 | -88 | -12 |

| Other industries | 14 | 162 | 8.7 |

| Total | 62 | -41 | -42 |

| FDI | |||

| Energy and mining | -7.3 | -136 | -28 |

| Finance and insurance | 5.1 | -33 | -2.4 |

| Management of companies and enterprises | 5.6 | -27 | -2.1 |

| Manufacturing | 6.4 | -66 | -13 |

| Trade and transportation | 9.6 | 3,453 | 9.4 |

| Other industries | 13 | 53 | 4.4 |

| Total | 32 | -49 | -31 |

Data source: Statistics Canada, Table 36-10-0026-01, May 31, 2021.

Calculation of the OCE.

FDI sources and CDIA destinations

The United States remains Canada's top investment partner. For 2020 overall, CDIA into the United States rose 7.9% to reach $37 billion in value, representing nearly 60% of the total CDIA for the year. However, FDI flows from the U.S. into Canada contracted over the past year, down 57% to $12 billion or 37% of the annual FDI flows into Canada.

CDIA flows into Hong Kong more than tripled in 2020. Consequently, Hong Kong became the second-largest CDIA destination for the year. Other significant CDIA destinations in 2020 include those in Latin America and the Caribbean, for example, Barbados and Mexico , as well as countries in Europe like the United Kingdom and Germany.

For inward FDI flows, the Netherlands was the second-largest investing country in Canada after the United States in 2020, up one spot from 2019 as FDI flows from Switzerland turned negative for the year. The United Kingdom trailed in third place. However, it is worth noting that since FDI flow figures capture the last country the investment was in before entering Canada, they may overstate the importance of certain intermediary investing countries such as the Netherlands and understate the size of investment from countries such as the United States, Brazil and China that hold larger stocks on an ultimate investing country basis. Chapter 2 provides a detailed explanation and discussion of FDI stock as measured on the basis of immediate or ultimate investing country.

Table 1.6 Canada's CDIA and FDI flows by destination and source (2020)

Value | Change | Change | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CDIA | |||

| United States | 37 | 7.9 | 2.7 |

| Hong Kong | 4.6 | 230 | 3.2 |

| Barbados | 4.4 | -40 | -2.9 |

| Mexico | 4.0 | 300 | 3.0 |

| United Kingdom | 3.0 | -63 | -5.0 |

| Germany | 1.8 | 11 | 0.2 |

| Australia | 1.5 | -198 | 3.1 |

| China | 1.2 | 100 | 0.6 |

| Netherlands | 0.9 | -58 | -1.3 |

| Japan | 0.3 | -312 | 0.4 |

| Cayman Islands | 0.3 | -91 | -2.7 |

| France | 0.2 | -70 | -0.5 |

| Brazil | 0.1 | -81 | -0.5 |

| Switzerland | 0.0 | -100 | -6.8 |

| Luxembourg | -0.9 | -113 | -7.5 |

| Other Countries | 3.6 | -89 | -28 |

| Total | 62 | -41 | -42 |

| FDI | |||

| United States | 12 | -57 | -16 |

| Netherlands | 3.8 | -46 | -3.3 |

| United Kingdom | 3.6 | 66 | 1.4 |

| France | 1.6 | -21 | -0.4 |

| Brazil | 1.6 | 1.7 | 0.0 |

| Cayman Islands | 0.9 | -77 | -3.1 |

| Germany | 0.8 | 76 | 0.4 |

| China | 0.4 | -60 | -0.7 |

| Barbados | 0.3 | 848 | 0.2 |

| Mexico | 0.2 | -1,446 | 0.2 |

| Japan | -0.3 | -213 | -0.5 |

| Luxembourg | -0.6 | -125 | -2.8 |

| Hong Kong | -0.9 | 54 | -0.3 |

| Australia | -1.8 | -177 | -4.2 |

| Switzerland | -4.2 | -154 | -12 |

| Other Countries | 15 | 186 | 9.7 |

| Total | 32 | -49 | -31 |

Data source: Statistics Canada, Table 36-10-0473-01, retrieved May 31, 2021.

Calculation of the OCE.

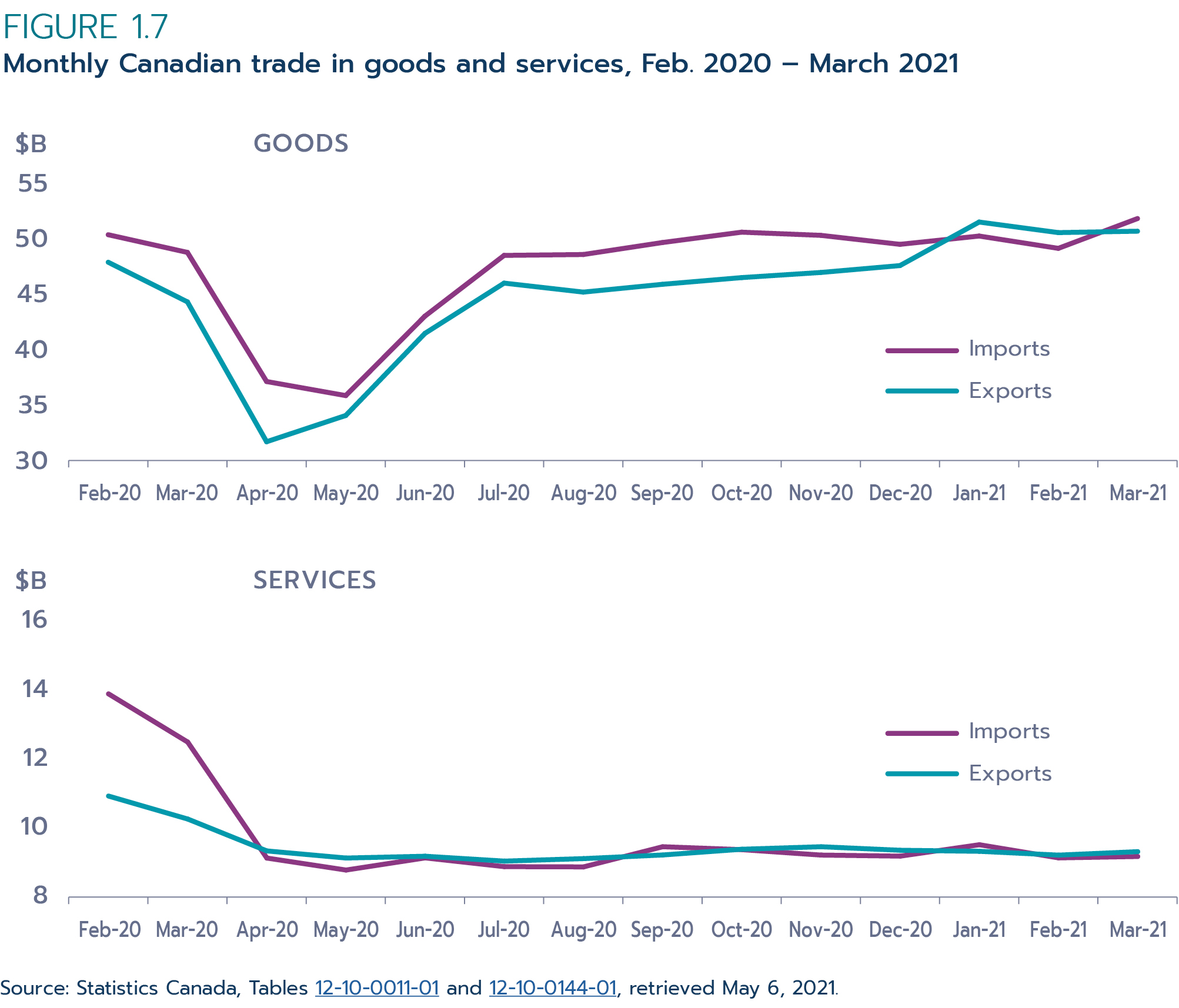

1.5 Q1 2021 trade update

Due in part to the spread of more contagious variants of the coronavirus, Canada experienced the peak of its second wave of the pandemic in the first quarter of 2021. Consequently, strict pandemic containment measures were re-implemented in hot zones, resulting in Canada's economic recovery decelerating to 5.6% in Q1 2021 (annualized). Further lockdowns represent another delay in recovery for many high-contact services industries, which have seen little improvements to economic activities since their initial crash in February.

Despite another slowdown in economic growth, both Canada's goods exports and imports have surpassed their respective pre-pandemic levels by the end of Q1 2021. In March 2021, Canadian goods exports were 5.9% above their level in February 2020. Among the sectors that registered strong export growth in the first quarter of the year, aircraft and other transportation equipment and parts, and energy products stood out, expanding by 44% and 31%, respectively. Furthermore, Canadian goods imports were 2.9% above their pre-pandemic level in March 2021, supported by strong growth in energy imports.

In contrast to goods trade, low levels of services trade persisted through the first quarter of 2021. As travel restrictions remained in place and the closure of the Canada-U.S. border continued to be extended, Canada's 2-way travel and transportation services trade remained far below pre-pandemic levels. By the end of Q1 2021, overall services exports and imports were 15% and 34% below their levels in February 2020.

Text version

Figure 1.7: Monthly Canadian trade in goods and services, Feb. 2020 ‑ March 2021

$ Millions

Goods

| Goods exports | Goods imports | |

|---|---|---|

| Feb-20 | 47.8 | 50.3 |

| Mar-20 | 44.2 | 48.7 |

| Apr-20 | 31.6 | 37.1 |

| May-20 | 34.0 | 35.8 |

| Jun-20 | 41.4 | 43.0 |

| Jul-20 | 45.9 | 48.4 |

| Aug-20 | 45.1 | 48.5 |

| Sep-20 | 45.8 | 49.6 |

| Oct-20 | 46.4 | 50.5 |

| Nov-20 | 46.9 | 50.2 |

| Dec-20 | 47.5 | 49.4 |

| Jan-21 | 51.4 | 50.2 |

| Feb-21 | 50.5 | 49.1 |

| Mar-21 | 50.6 | 51.8 |

Services

| Services exports | Services imports | |

|---|---|---|

| Feb-20 | 10.9 | 13.8 |

| Mar-20 | 10.2 | 12.5 |

| Apr-20 | 9.3 | 9.1 |

| May-20 | 9.1 | 8.8 |

| Jun-20 | 9.2 | 9.1 |

| Jul-20 | 9.0 | 8.9 |

| Aug-20 | 9.1 | 8.9 |

| Sep-20 | 9.2 | 9.4 |

| Oct-20 | 9.4 | 9.3 |

| Nov-20 | 9.4 | 9.2 |

| Dec-20 | 9.3 | 9.2 |

| Jan-21 | 9.3 | 9.5 |

| Feb-21 | 9.2 | 9.1 |

| Mar-21 | 9.3 | 9.1 |

Data source: Statistics Canada, Tables 12-10-0011-01 and 12-10-0144-01, retrieved May 6, 2021.

Take-home messages

- The year 2020 was marked by historical challenges to the global economy and trade due to the pandemic. Canada was not spared as it registered its largest annual economic contraction since comparable data were first recorded.

- While Canada's economy saw strong recovery in the second half of 2020, it was not enough to offset the loss in the first half, with many services-producing industries continuing to struggle by the end of the year.

- While the economy was harder hit by the pandemic than by the GFC, Canada's trade and FDI flows declined less because of the pandemic than they did from the GFC.

- International trade was one of the hardest-hit aspects of the Canadian economy. Due mainly to lower bilateral trade with the United States, both Canadian exports and imports suffered double-digit declines.

Chapter 2: FDI as a driver of domestic growth

Over the past 30 years, we have seen tremendous growth in global FDI. The world's economies are becoming increasingly interdependent through the cross-border flow of goods and services, investment, technology, information and people. Many of the largest firms around the world have significantly grown their global footprints with increased sales to foreign markets and investment in those markets through the establishment of foreign affiliates. For many of the world's largest companies, foreign markets account for the majority of their sales, assets and profits (UNCTAD, 2019).

As an open economy, Canada relies on foreign investment and international trade to drive its growth. In fact, the country's dependence on foreign capital and trade has been a characteristic of Canada's economy for most of its history, starting with British investment in the mid-19th century in the country's railways, canals and other public works. The early part of the 20th century saw the growth of investment from the United States in the resource and manufacturing sectors.

FDI in Canada has grown considerably since the 1980s. The stock of FDI was equivalent to 47% of Canada's GDP in 2020—almost 30 percentage points higher than in the late eightiesFootnote 3 (Box 2.1). This growth has led to debates about its impact on the Canadian economy and, more specifically, whether this investment is coming at the cost of jobs at home or, alternatively, helping to support Canadian firms' competitive position as they access new markets and resources. These are important questions, as determining the impact of FDI can have important implications for the design of investment and trade policies to promote economic growth.

Box 2.1: Understanding FDI

Foreign direct investment occurs when an investor in one economy obtains a "lasting interest" in an enterprise resident in another economy. The lasting interest implies that a long-term relationship exists between the investor and the enterprise and that the investor has a significant influence on the way the enterprise is managed. Such an interest is deemed to exist when a direct investor owns 10% or more of the voting power on the board of directors (for an incorporated enterprise) or the equivalent (for an unincorporated enterprise).

FDI statistics are presented as a financial flow (transaction) or stock (position). FDI flows represent activities of foreign investors over a period of time (e.g. in a given year). FDI flow data also include the return on equity and debt in the form of profits and interest income to the direct investor during a specific period of time. FDI flows can be quite volatile (McNaughton, 2021)—just one large deal in a given quarter or year can have a huge impact on the flow figures for that time period. FDI stocks represent the total foreign investment at a point in time—i.e. the cumulative value of investments. FDI stock includes equity and debt (loans between companies).

Total FDI flows, or investments, in a given year impact the total FDI stock or the FDI "position". Furthermore, flows can often be negative, as in the case of divestitures and repatriation of earnings when money flows back to the foreign parent company. Affiliate earnings that are reinvested in the affiliate rather than repatriated count toward FDI flows in a given year.

Text version

Total FDI flows, or investments, in a given year impact the total FDI stock or the FDI "position". Furthermore, flows can be negative, as in the case of divestments and repatriation of earnings. In both cases, money flows back out of Canada to the foreign parent company. Reinvested affiliate earnings in the affiliate rather than repatriated count toward FDI flows in a given year.

2.1. Benefits of inward FDI

Evidence from around the world suggests that there are many benefits for host economies that have the appropriate policies, infrastructure and skill base to take advantage of foreign investment.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) summarized the merits of inward FDI as follows:

"Given the appropriate host-country policies and a basic level of development, a preponderance of studies shows that FDI triggers technology spillovers, assists human capital formation, contributes to international trade integration, helps create a more competitive business environment and enhances enterprise development." (OECD, 2002)

In other words, foreign firms or affiliates:

- bring new technology and know-how

- contribute to skills upgrading of local workers

- boost supply chain integration and international trade

- foster competition among domestic firms

This, in turn, can lead to better quality and increased variety in goods and services. Innovation, technology adoption, a highly skilled workforce and increased competition among firms all drive productivity, the key determinant of income per capita, or standard of living, in the long term.

Furthermore, foreign investment provides capital to finance new investments and enhance existing businesses. Between 2007 and 2020, foreign companies injected an average of $53 billion a year into the Canadian economy both through new capital investments as well as through the reinvestment of profits made in Canada. Reinvested earnings, or earnings from foreign affiliates invested back in the Canadian economy rather than repatriated, account for one third of this amount.Footnote 4

The extent to which inward FDI affects a host economy depends on a number of factors including the sector in which the FDI occurs as well as the entry mode: a greenfield investment or a brownfield investment, such as a merger or acquisition (M&A) (Box 2.2). Technology spillovers may be more pronounced with M&As given that companies already have established supply-chain linkages. However, newly established affiliates, or greenfield investments, imply an expansion of the existing capital stock in an economy, thus additional economic activity related to job creation and investment in capital, such as machinery and equipment.

Box 2.2: FDI mode of entry: greenfield versus brownfield

When a company decides to establish new operations in another country or expand its international operations through FDI, this investment can be in the form of either new or existing facilities. These 2 types of investment are usually referred to as greenfield or brownfield investments.

In a greenfield investment, the parent company establishes a subsidiary in another country and constructs new facilities from the ground up. The new facilities may include a production plant, distribution or sale facilities, and office space, depending on the industry. Goods-producing industries require a production plant while service industries may only need office space. There are several reasons why a company may decide to build a new facility rather than purchase or lease an existing one. The primary reason is that a new facility offers design flexibility along with the efficiency to meet the project's needs. If the company wants to advertise its new operation or attract employees, new facilities also tend to be more favorable.

Brownfield investments occur when an enterprise purchases or leases an existing facility to begin new operations or expand existing operations. Companies may consider this approach if they do not want to incur the start-up costs typically associated with greenfield investment and/or their needs can be easily addressed by available vacant spaces. With this type of investment, a company will typically either invest in existing facilities and infrastructure through leasing or acquiring existing vacant facilities in a foreign country or a merger and acquisition (M&A) deal.

Some of the advantages of this type of investment may include:

- the ability to quickly gain access to a new foreign market

- lower start-up costs due to the facilities already having been established

- existing approvals and licences from governments or regulators

Greenfield investment is of particular interest to researchers and policy-makers, but at present the official statistics do not report this type of FDI separately. Currently, there are no internationally agreed upon definitions of greenfield FDI, and it is challenging to precisely distinguish greenfield investments from expansion investments, which extend the capacity of existing businesses (IMF, 2021). In Canada, official FDI data on greenfield investments are currently included in the "other flows" category in Statistics Canada's quarterly FDI series. However, the "other flows" category also includes debt transactions between parent companies and their subsidiaries as well as flows that may be related to financial restructuring of the greenfield.

In May 2021, Statistics Canada released a new data table, Table 36-10-0656-01, that provides direct investment flows on a gross and net basis. These data were made available in an effort to further define the nature of FDI in Canada. Data can be disaggregated according to 2 industry groupings (goods and services producing industries).

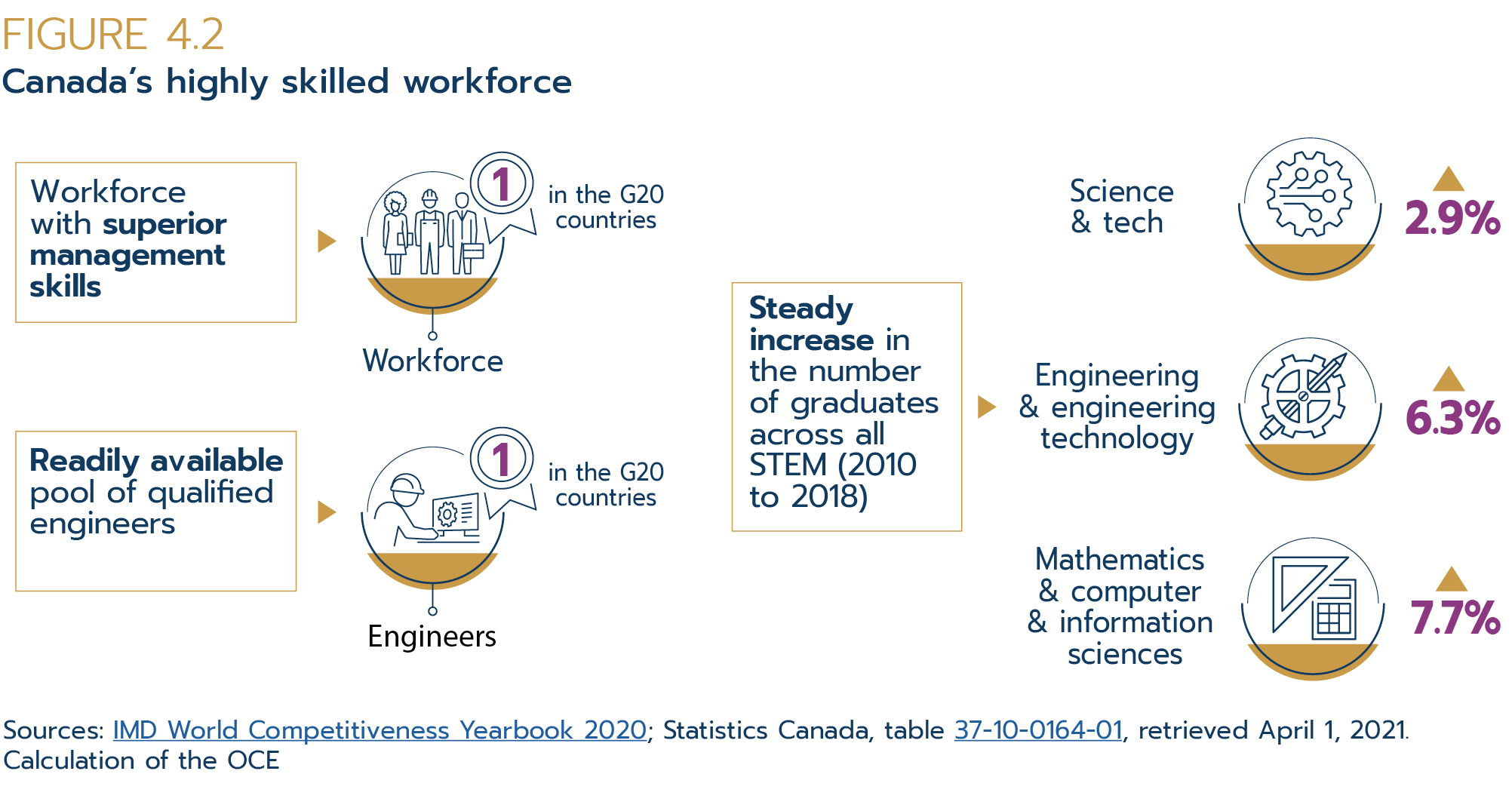

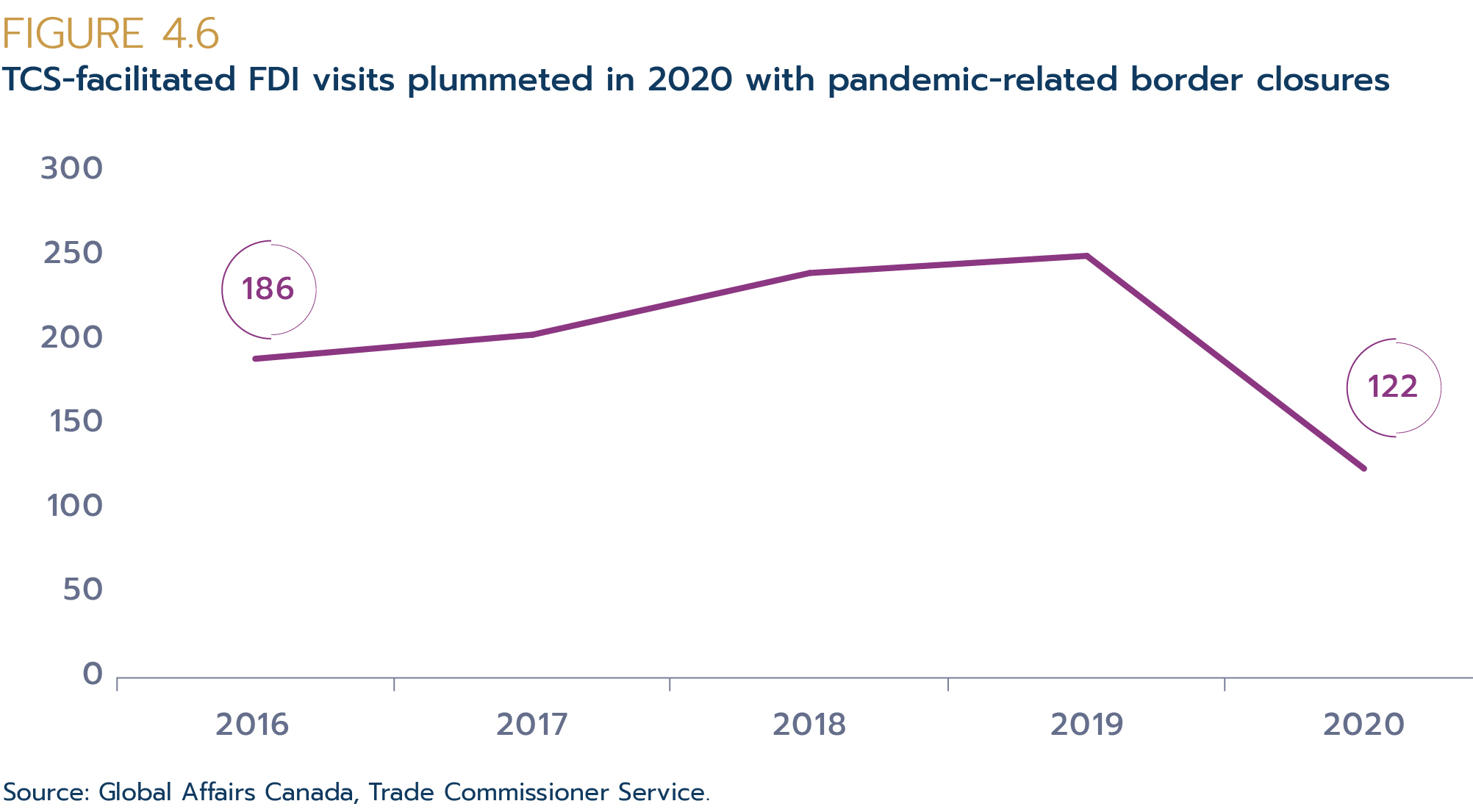

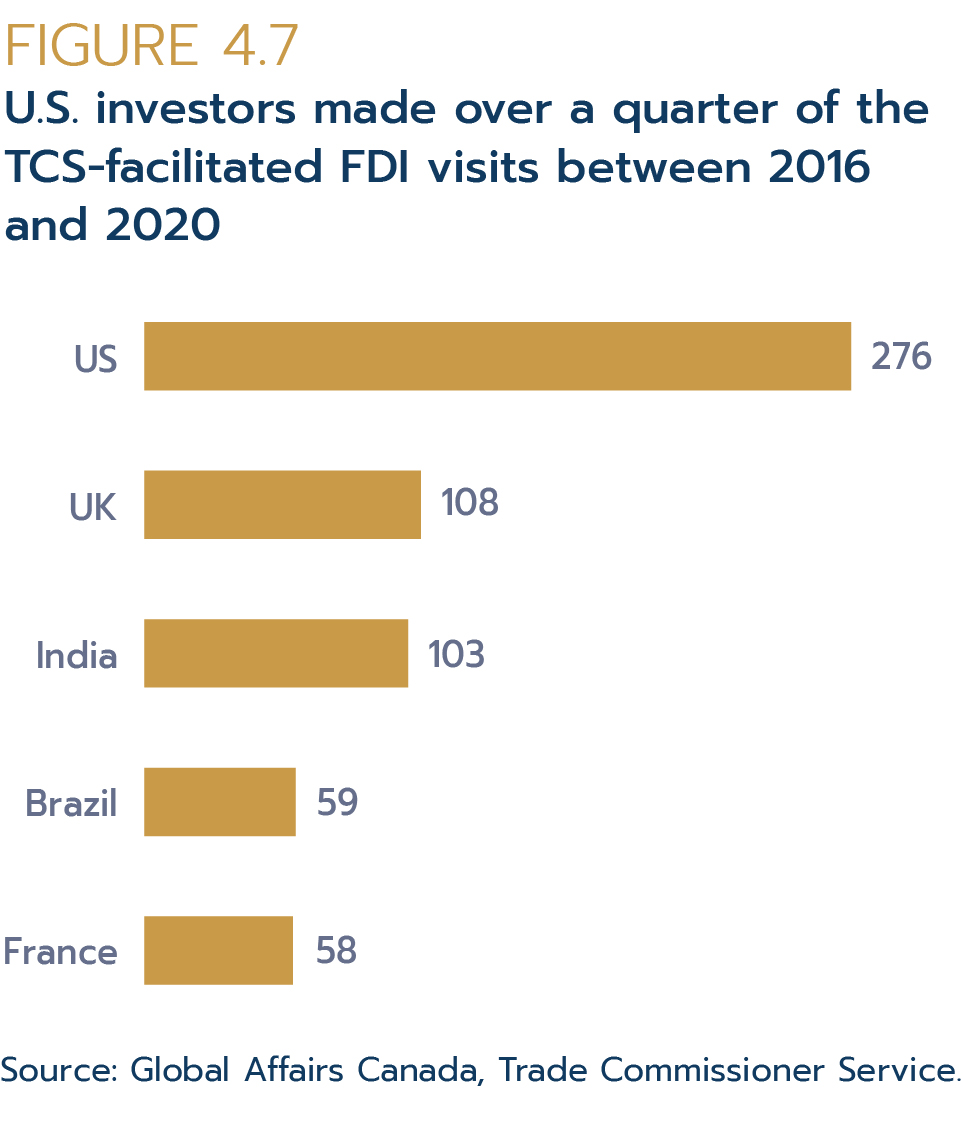

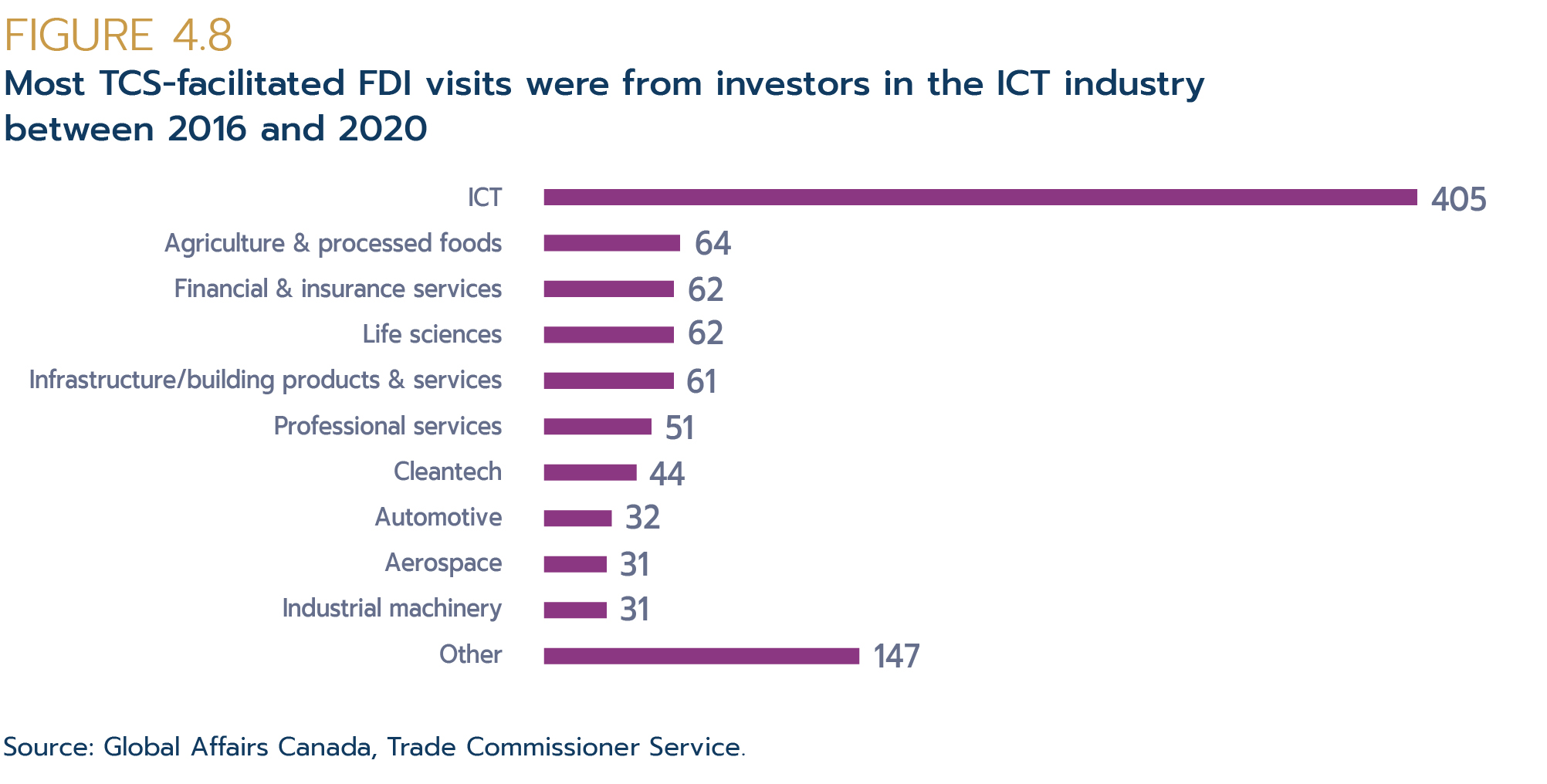

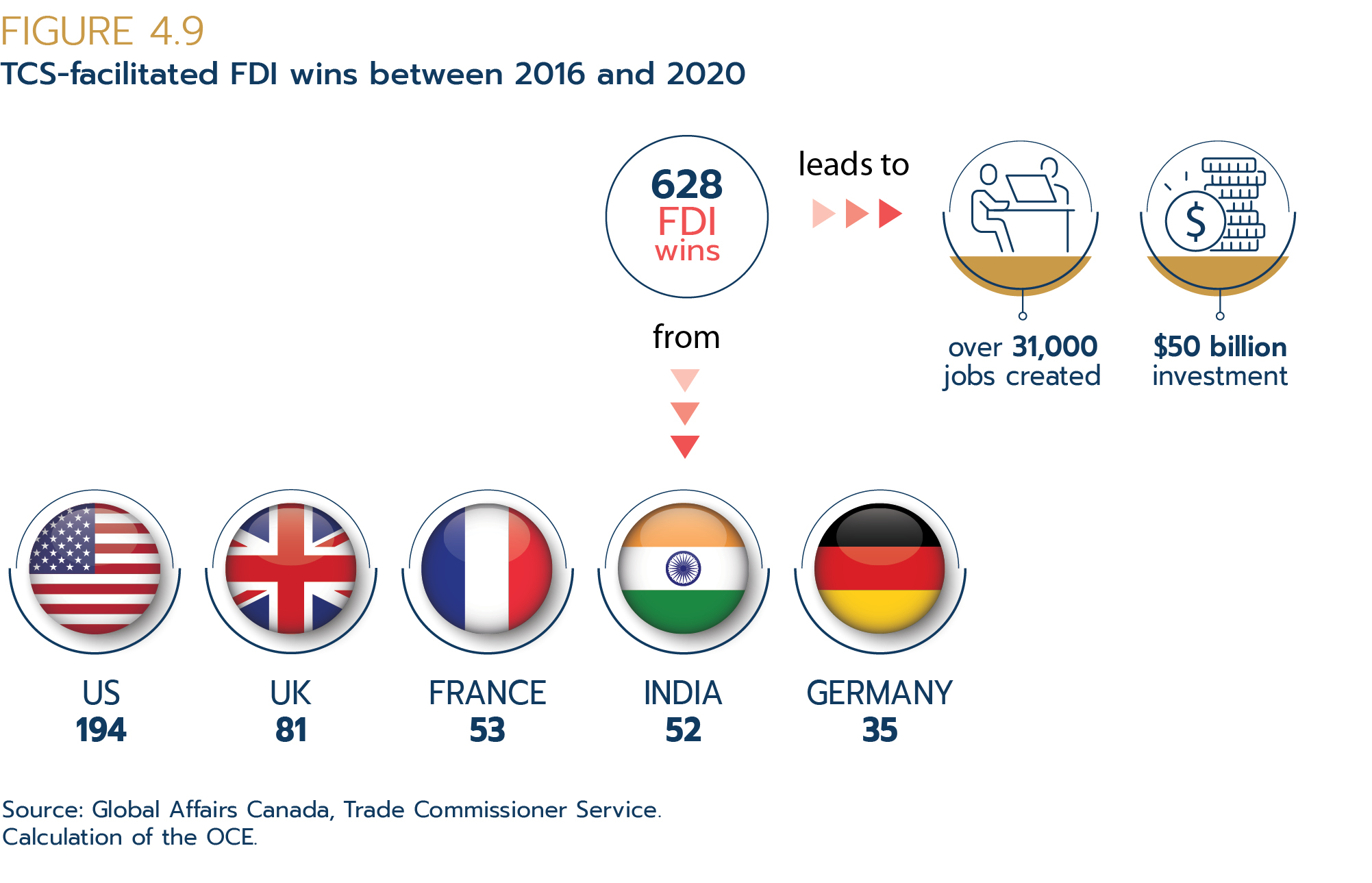

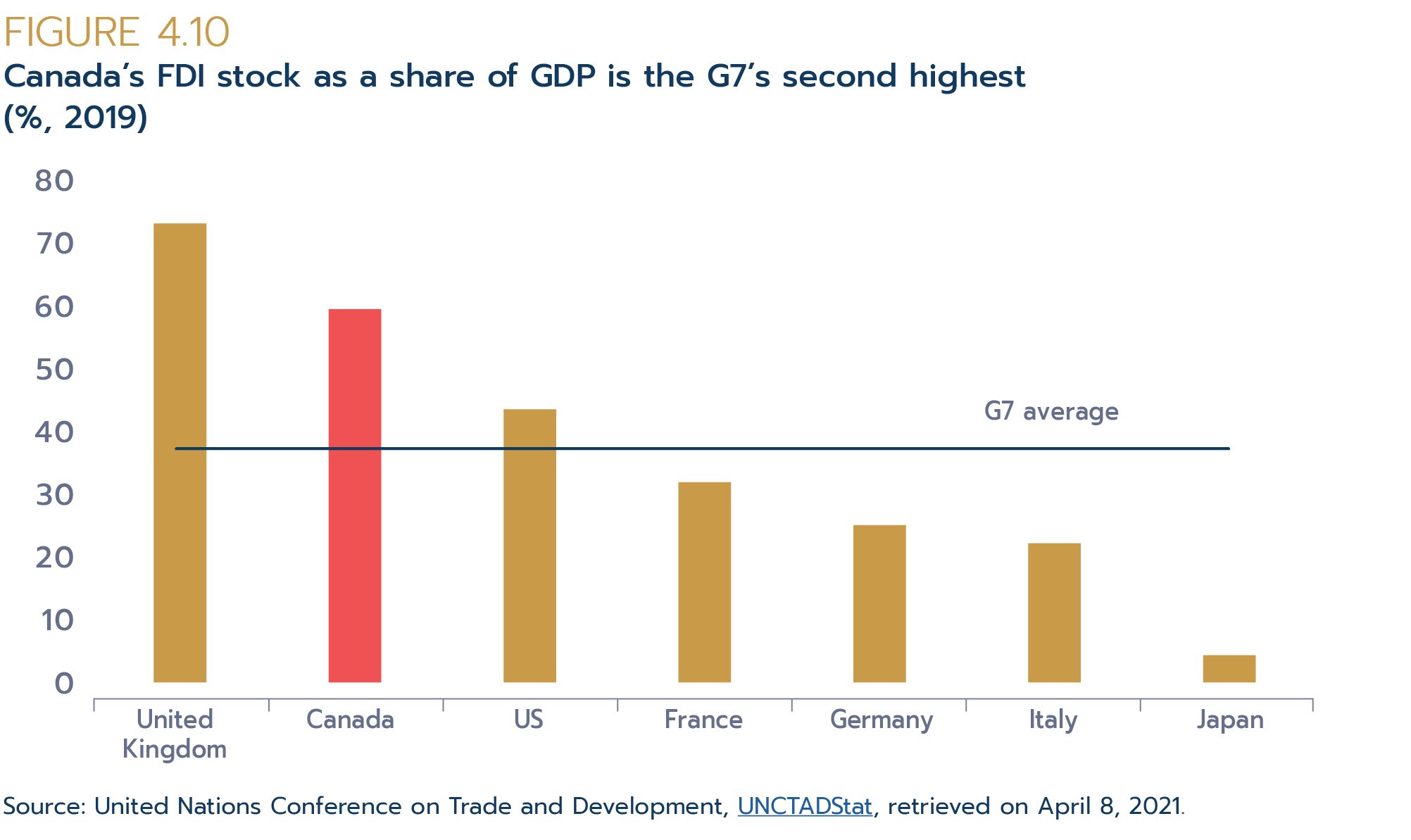

Studies of the impact of FDI in Canada demonstrate the positive relationship between foreign investment and productivity. Multinational firms are more productive than purely domestic firms (Rao and Tang, 2005; Baldwin and Gu, 2005; Tang and Wang, 2020). There is strong evidence for productivity spillovers from foreign plants to domestic ones as a result of increased competition and greater use of new technologies among the domestic firms. FDI has resulted in inter-industry productivity spillovers in Canadian manufacturing industries, via both upstream and downstream production linkages (Wang and Gu, 2006). One study (Baldwin and Gu, 2005) estimates that foreign firms accounted for over two thirds of labour productivity growth in Canada's manufacturing sector in the 1980s and 1990s.