Global Affairs Canada’s Office of the Well-being Ombud and Inspector General’s first annual Ombud Report 2023 to 2024

ISSN 2818-7954

A message from the Well-being Ombud

In my first message to you as Global Affairs Canada’s Well-being Ombud, I mentioned the words inscribed in the pavement at the entrance to the building in which I work: “Speak Up - Prenez la parole.” During my first year, the words “Speak Up” have served as a daily reminder to me of my role and the role of the experts and professionals in the Office of the Well-being Ombud and Inspector General as we work to support a healthy work environment at GAC’s offices, at home and abroad.

At its heart, our office is a safe place where you can speak without fear of judgment or reprisal. Our goal is that in speaking up you lighten your load, identify your options and define a pathway forward when you are facing what can feel like insurmountable—sometimes impossible—situations.

I have had unique opportunities to witness the complexities of GAC’s work and been given a special window into understanding some of the challenges you face. I have seen how you strive with pride to deliver a complex and challenging mandate on behalf of Canada around the world while confronting difficult situations both at work and because of your work.

When I first met with Deputy Minister David Morrison last year, he said that at the heart of my role was keeping a finger on the pulse of our organization. This report—which has been independently prepared by our office—represents what we have heard from you over the last fiscal year (April 1, 2023, to March 31, 2024). Generally, you call us when things are tough, and so the issues raised in this report largely relate to challenging situations of stress, crisis and interpersonal conflict. These issues are significant—not only because so many of you reached out to us about them but also because of the impacts these issues have on you, your families and your colleagues, both at work and at home.

We have heard about your expectation for more transparent, more respectful and more compassionate management practices. You have shared your experiences coming up against barriers to your active participation in work life, and spoken of painful experiences of disrespect, harassment and discrimination in the workplace. You have spoken of the impacts of geopolitical crises on your working relationships and on your mental health and well-being. And you and your families have shared with us the very specific challenges you face in advancing GAC’s mandate, whether you serve at home or abroad.

Some of you will read this report and see yourself in it. Some of you will be reading it expecting a call to action for the department. While you will not find recommendations in this, our first annual report, and you will not find every experience or conversation chronicled here, I hope you will see an honest reflection of the range of issues faced by our people at home and abroad. For anyone reading this who is struggling with work-related or personal issues, I hope that this report shows that you are not alone and that there is always someone you can turn to. I encourage you to reach out to us to let us know what you think of the report and its contents, including what surprised you and what we missed.

In building the Office of the Well-being Ombud and Inspector General, we are, I hope, helping our department develop a culture that fosters psychological safety, genuine trust in each other and mutual respect among each and every one of us. Our office is just over a year old. We are a work in progress, and the work to deliver on our mandate is very much a team effort. Thank you to my predecessor, Rob Sinclair, to my deputy ombud, Daniel Campeau, and to all those who have contributed to the development of the office and to this first annual report.

This report is your report—it reflects your experiences as shared with me and with our team. Thank you for the trust you have placed in us and for the courage you show every time you speak up.

Ayesha

Ayesha Rekhi

Well-being Ombud

About this report

The observations in this report are based on the experiences of people who have used the services of the ombud office. This report is meant to provide a window into some of the situations people working at GAC have experienced, but by no means does it speak to everyone’s experience in our organization. The people who have used the services of our office are often facing difficult and challenging situations. The information in this report reflects what they have shared with us. As a result, you may find the tone of this report to be more conversational and informal than what you might expect in a “traditional” annual report.

Our guiding principles

The Office of the Well-being Ombud and Inspector General helps GAC employees and managers support well-being and management effectiveness across the department, at home and abroad.

We are a companion to employees and managers, helping you better understand the issues and available options to address your concerns. When you find yourself in a challenging situation at work or in your personal life and decide to reach out to us, we will actively listen to what you have to say. We will reflect with you on the available options and discuss next steps and the range of actions you can take to resolve the situation.

We are a safe and confidential first port of call for many of you when you are not sure what to do about a situation. Our work is framed by 4 guiding principles: confidentiality, informality, impartiality and independence.

Confidentiality

You may be hesitant to come forward with your issues if you fear that your personal information will be shared with others without your permission. Confidentiality is key to our ability to provide support to you, build trust and maintain the integrity of our office. By assuring confidentiality, we create a safe space for you to voice your concerns and seek assistance without fear of reprisal or judgment.

When you speak to us, what you share is kept in strict confidence, unless you give us permission to raise the issue with the appropriate person. Before we would do so, we would carefully discuss the advantages and the potential risks with you. There are some important exceptions: if there is a risk of serious harm to you or someone else or if there is a serious allegation of criminal behaviour.

Informality

When you talk to us, the conversation is voluntary and off the record. By using our services, you have the chance to discuss different ways to solve your problem. You can choose an informal option to try to fix things or opt for a more formal route if that feels right for you. We are here to act as a sounding board so that you can figure out what is best for you. Being informal can be helpful when you are making decisions. If you tackle issues in a calm way, you might come up with some new ideas to address what you are experiencing.

The words we use are important. We call people who use our services “visitors” because they come to us by choice. The word “visitor” helps make it clear that we do not take sides. We do not refer to those who reach out to us as “clients” or “complainants” because the purpose of the process is to talk things through informally, not to make a formal complaint. Anyone who needs guidance or wants to solve a problem can come to us, whether they are Canada-based staff (CBS), locally engaged staff (LES), employees or managers, or even a family member.

Impartiality

We do not advocate in favour of the employer, nor do we advocate for your individual situation. This can be difficult for our visitors to accept, but being impartial allows us to help identify and explore a range of options to address a situation you may be facing with a focus on fairness and well-being. Impartiality also allows us to build trust with all parties involved in an issue and to maintain positive relationships and productive collaborations.

The words we use are important. We call people who use our services “visitors” because they come to us by choice. The word “visitor” helps make it clear that we do not take sides. We do not refer to those who reach out to us as “clients” or “complainants” because the purpose of the process is to talk things through informally, not to make a formal complaint. Anyone who needs guidance or wants to solve a problem can come to us, whether they are Canada-based staff (CBS), locally engaged staff (LES), employees or managers, or even a family member.

Looking for advice? The difference between advice and guidance

Our office provides guidance to employees and management to navigate situations and to explore options.

Providing advice

Advice:

- is a subjective and personal set of instructions or recommendations for a specific product or action

- offers recommendations on what you should do based on individual circumstances

Example: Seeking advice from your union representative on filing a grievance

Providing guidance

Guidance:

- is an unbiased service that helps individuals identify choices

- offers decision support: does not offer a specific choice but empowers you to make your own decisions

Example: Looking for tips or coaching on how to have a difficult conversation

If you are an employee represented by a union or collective bargaining agent, you can seek advice from your union or agent. If you are a manager, GAC’s Labour Relations Division (HWL) or HR Operations (LES) Division (HLDS) will provide you with advice.

Independence

The Well-being Ombud reported directly to the Associate Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs for the period covered in this report. Because the office stands alone as a special bureau and is not part of a larger branch, we are able to work with people across the department in a positive, constructive way. We are also able to raise concerns, patterns or issues that people have mentioned over time, and we can shine a light on these for senior management and for the department, including via this report.

What do we do when we hear about problematic patterns of behaviours or other serious concerns?

The role of an organizational ombud in raising red flags is crucial to ensuring transparency, accountability and fairness in an organization. We can help to identify and address potential issues before they escalate into more serious problems for individuals, teams and the organization as a whole. We can proactively bring issues to the attention of senior management, and because of our principles we can help to prevent further harm by protecting the identity of visitors who have trusted us with their information. This proactive approach can help to contribute to building a healthier work environment for our colleagues, maintain the integrity and reputation of our department and support efforts to ensure accountability.

In 2023-24, the ombud spoke regularly to senior management to raise issues of concern, shared trends data through bimonthly reports, and formally reported to GAC’s Executive Committee on April 11, 2024.

The ombud also helps to identify systemic issues at GAC. The ombud can pinpoint areas where policies, procedures or practices may need some attention to prevent similar issues from arising in the future. This proactive approach can help to strengthen the overall governance and operations of our organization, contributing to better outcomes for all.

Our services

Ombud services

When you reach out to us, we will help you to address your situation and navigate the system. Our services have been built around the long-standing services offered by GAC, including the Employee Assistance Program (EAP) and Informal Conflict Management Service (ICMS), and that now also include Ombud Services with an organizational mandate. When you have a confidential conversation with the ombud, deputy ombud or staff, including our dedicated adviser for LES issues, we:

- listen to understand issues from your point of view

- reframe them to develop potential options for resolution

- guide you in dealing directly with other people and improving your skills in addressing concerns, including referring you to other services if that is what you want

The ombud also identifies potential red flags for the organization and raises systemic issues with senior management. We talk to your employee networks, equity-seeking champions and representatives, unions and bargaining agents, and other stakeholders. We provide high-level recommendations, analyses and options on management best practices through regular conversations with senior management.

Values and ethics, advice and investigation functions

To respect our guiding principles, the functions of values and ethics, advice and investigations were transferred to other branches:

- HWP: Values and ethics advice and investigations (valuesandethics-valeursetethique@international.gc.ca)

- VBZ: Investigations under the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act (disclosure-wrongdoing.divulgation-acte-reprehensible@international.gc.ca) and

- Special investigations of financial fraud, malfeasance and losses of money and/or property to the Crown (SpecialInvestigations@international.gc.ca)

Centralized intake services

Our centralized intake service is often the first place to go to access our services. During Ottawa business hours, we aim for our intake officer to respond to your message within 24 hours. Our goal is that one of our counsellors or practitioners will then contact you within 48 hours to offer you an appointment within 2 weeks of your having contacted us. Help outside of regular Ottawa business hours is arranged between you and the member of our team with whom you are working. You can be assured that we take steps to be accessible to our missions, whatever the time zone.

A single easy email address to access our services

You can reach us at ombud@international.gc.ca to access any of our services, including:

- Ombud Services

- The Employee Assistance Program

- Informal Conflict Management Service

Please note: The email address solution@international.gc.ca is no longer active.

Employee Assistance Program

The Employee Assistance Program (EAP) is a voluntary and confidential service available to assist individuals facing personal and professional challenges. Our EAP counsellors are here to help you make sense of what you are going through in your personal life or at work, and they work with you to identify the appropriate help. We also give managers tips on how to deal with difficult situations between people at work. Plus, we create and run custom training for staff on various issues related to psychological health and staying resilient. Finally, we provide support to individuals and groups during and after a potentially traumatic event.

Psychological health: This refers to emotional, cognitive and social well-being. It includes how we think, feel and interact with others. A person with good psychological health can manage stress, maintain healthy relationships and cope effectively with life’s challenges.

Why is the Employee Assistance Program in the Office of the Well-being Ombud?

Ombuds help organizations to be fair and transparent, and they often work on issues that can be emotionally intense. By adding counselling services to the ombud office at GAC, we are meeting the special needs of our employees and their families, both in Canada and abroad. GAC works all over the world, with offices in 5 regions and in 182 international locations. Offering counselling within our office means that people can easily find help and information for dealing with tough situations while trusting the confidentiality of the services being provided. We provide easy access to professionals and experts who can assist with stress, worry and interpersonal problems that could lead to challenges at work.

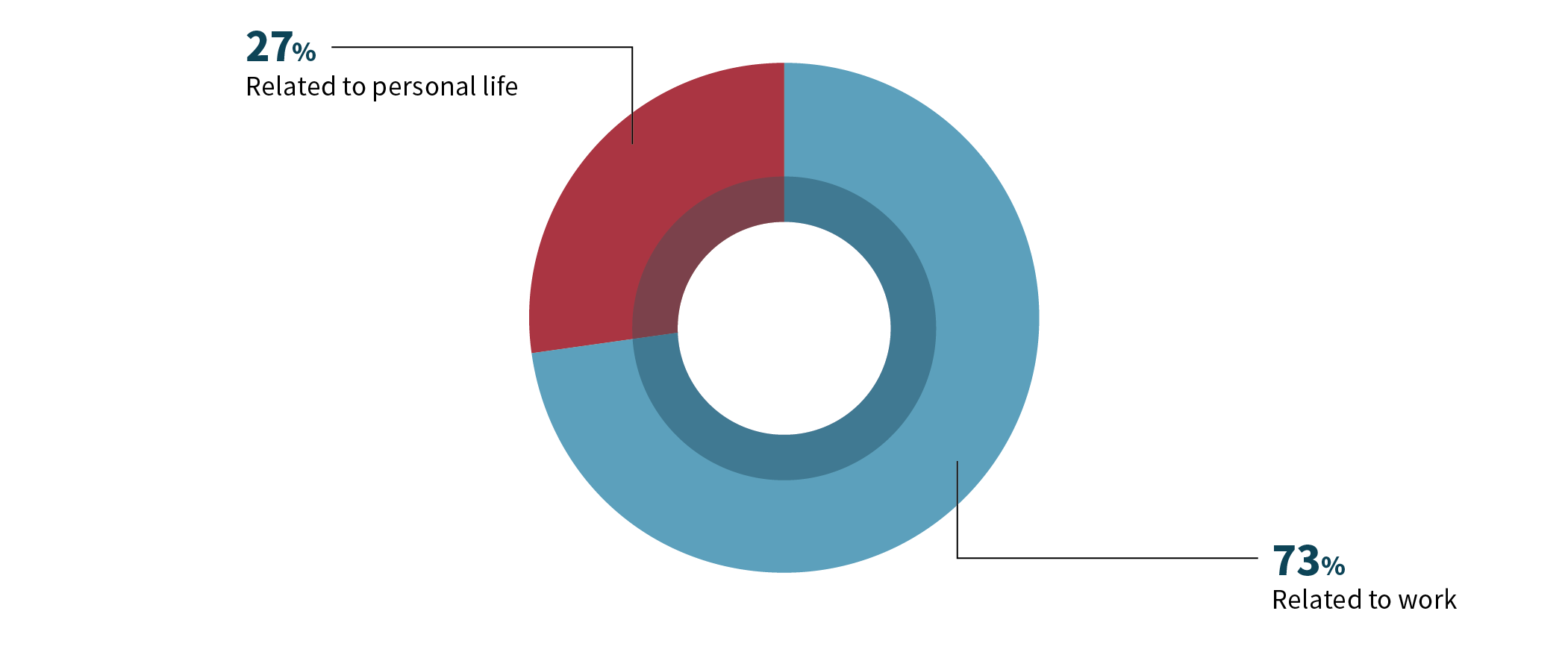

The chart below shows the split between work-life and personal-life issues that visitors raised with our EAP counsellors in the past year. Visitors reached out to us to get support related to their work at 48% and support for personal issues at 52%.

Text version

Employee Assistance Program: Work-life vs personal-life issues

Related to work: 48%

Related to personal life: 52%

Informal Conflict Management Service

The Informal Conflict Management Service (ICMS) is a voluntary, informal approach to help with workplace issues. ICMS offers different kinds of support like one-on-one coaching, helping people talk things out through facilitated conversations and mediation. Our goal is to improve communications, help teams work well together and create a positive, productive and healthier work environment.

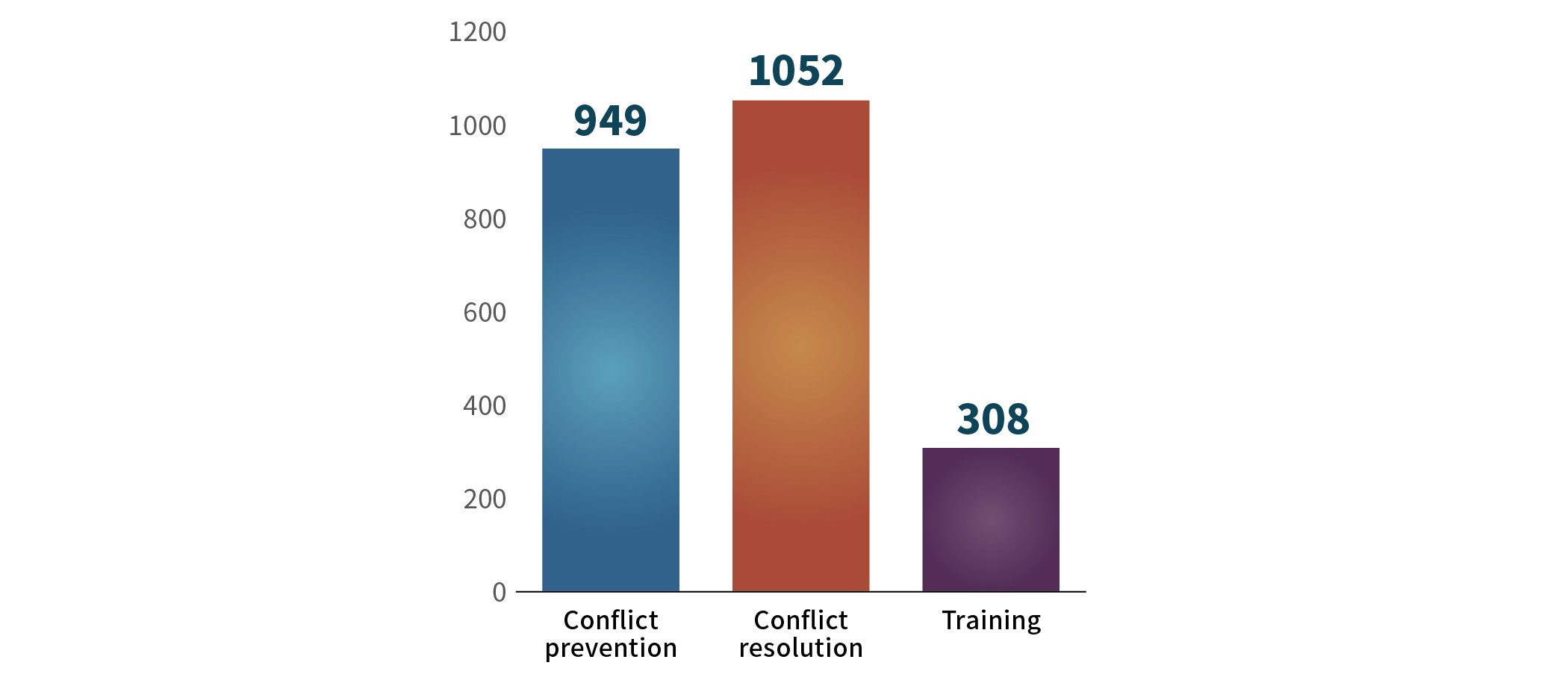

This graph details the number of interventions provided by our ICMS team in the past year. The team delivered a total of 2,309 sessions: 949 for conflict prevention; 1,052 for conflict resolution; and 308 for general training.

Text version

| Informal conflict-management services | Number of sessions |

|---|---|

Training | 308 |

Conflict resolution | 1,052 |

Conflict prevention | 949 |

Mission inspections

The well-being ombud is also GAC’s inspector general. While both roles are part of a continuum of support for GAC’s managers and employees, the roles are distinct but complementary in supporting positive organizational change. This is an ombud report and does not cover mission inspections. Inspections are a more formal but still independent process with a focus on leadership, management excellence, management effectiveness and well-being. Inspections, including e-inspections, look at what is working well at a mission, identify things to watch and spotlight areas for attention and action. Inspection results are shared with mission management and senior managers at Headquarters. The inspector general also discusses results with the deputy minister and the associate deputy minister. While still respecting privacy and confidentiality, heads of mission are expected to share inspection results with their teams. The main goal of inspections is to give constructive feedback to managers so that missions and our people at our missions can do their best work.

What happens when an employee raises serious concerns during an inspection?

If you tell an inspector about an issue affecting your well-being, they will keep it confidential. They might suggest you talk to the ombud office or, in the case of specific and serious issues, may ask your permission to talk about the situation with other parts of the department. Because any concerns you share through an e-inspection are anonymous, the inspector general will not be able to follow up with you directly.

Our reach: The numbers

In the previous section, we told you about the individual services that we offer to you. We also gather organizational data on the department’s overall psychological health and provide data and analysis to help senior management stay aware of important issues and trends. This work includes a bimonthly statistical report on issues that have most often been brought to our attention. We send this report to all heads of mission and to senior managers at headquarters. It also includes this annual report highlighting major issues raised with us from the past year.

Finding ways to respect and protect you while sharing our analysis of issues and trends with the department is key to supporting positive changes in behaviours and in our organizational culture. Confidentiality matters to us, and we know it matters to you. It is key to our ability to provide you with a safe space. When producing reports, we review them to ensure that no information could potentially lead readers to identify specific individuals. Even in our day-to-day work, we do not keep formal case files, and we work hard to exclude any details from our correspondence that might compromise the confidentiality of our exchanges. If you see yourself in this report, know that what we are sharing is not about your specific situation; rather, it reflects the fact that many of you shared a similar experience with us, and that’s why we chose to spotlight it here.

The following section is a representation of our interactions with you in numbers. We hope that by sharing our numbers we can facilitate reflections on key issues facing teams, spark conversations among yourselves, your teams and management, and encourage compassionate responses and effective actions that will enhance employee well-being.

Demand for our services

Our team has been actively engaging with many of you as you share your challenges, work through your options and manage your next steps. In 2023 to 2024, we engaged in 5,296 sessions that involved 9,809 people.

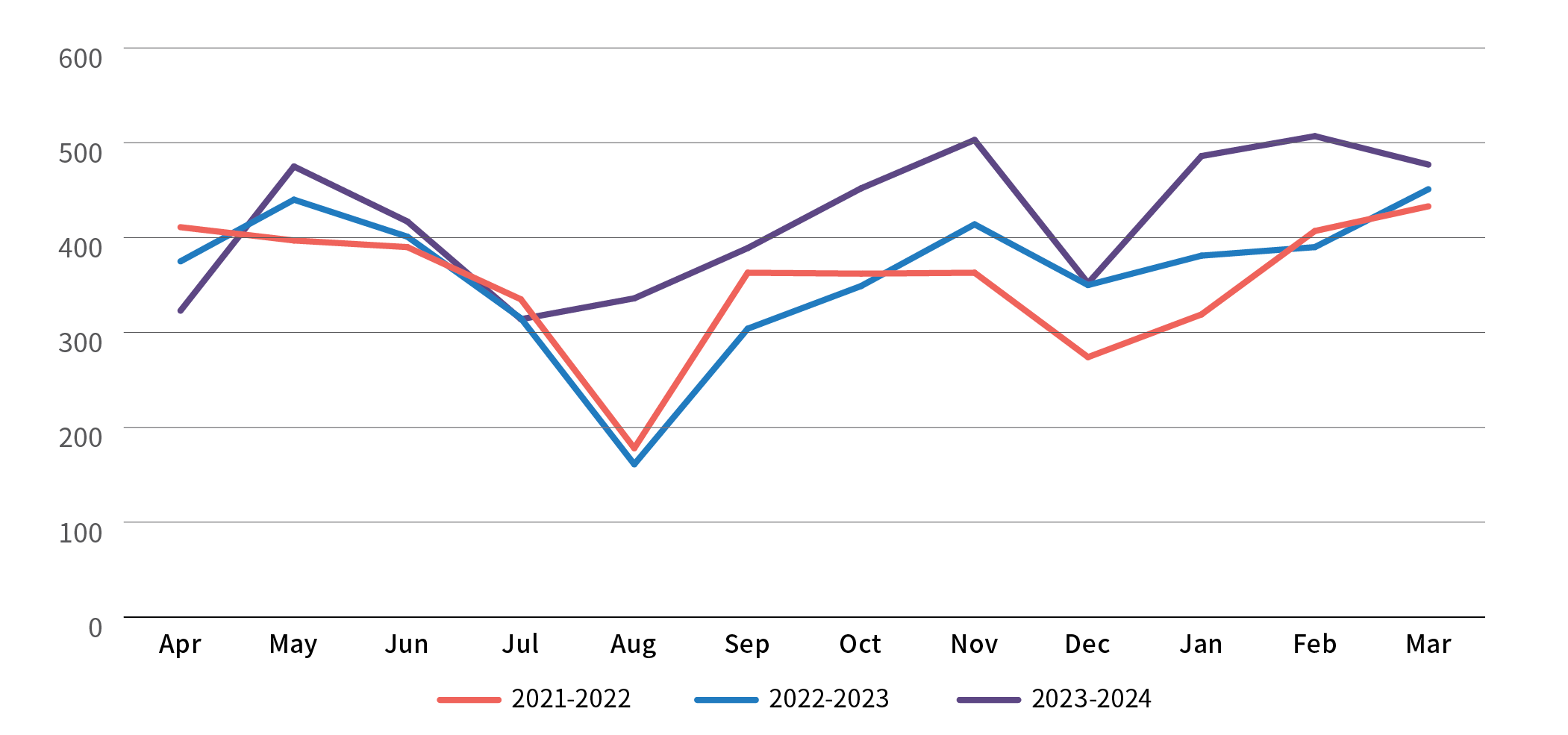

The following chart shows the number of sessions that were held each month in 2021 to 2022, 2022 to 2023 and 2023 to 2024. Sessions include everything from one-on-one visits to group interventions and trainings. The up-and-down trend line follows a typical pattern from year to year, and reflects the normal cyclical nature of our busyness, with things quieting down during the summer months when many employees are on holiday or involved in a rotation period. Requests for support tend to pick up each September, then slow down again around the winter holidays and then pick up again in the new year.

Text version

Number of sessions per month

| Month | 2021-2022 | 2022-2023 | 2023-2024 |

|---|---|---|---|

April | 411 | 375 | 323 |

May | 397 | 440 | 475 |

June | 390 | 401 | 417 |

July | 335 | 315 | 314 |

August | 178 | 161 | 336 |

September | 363 | 304 | 389 |

October | 362 | 349 | 452 |

November | 363 | 414 | 503 |

December | 274 | 350 | 352 |

January | 319 | 381 | 486 |

February | 407 | 390 | 507 |

March | 433 | 451 | 477 |

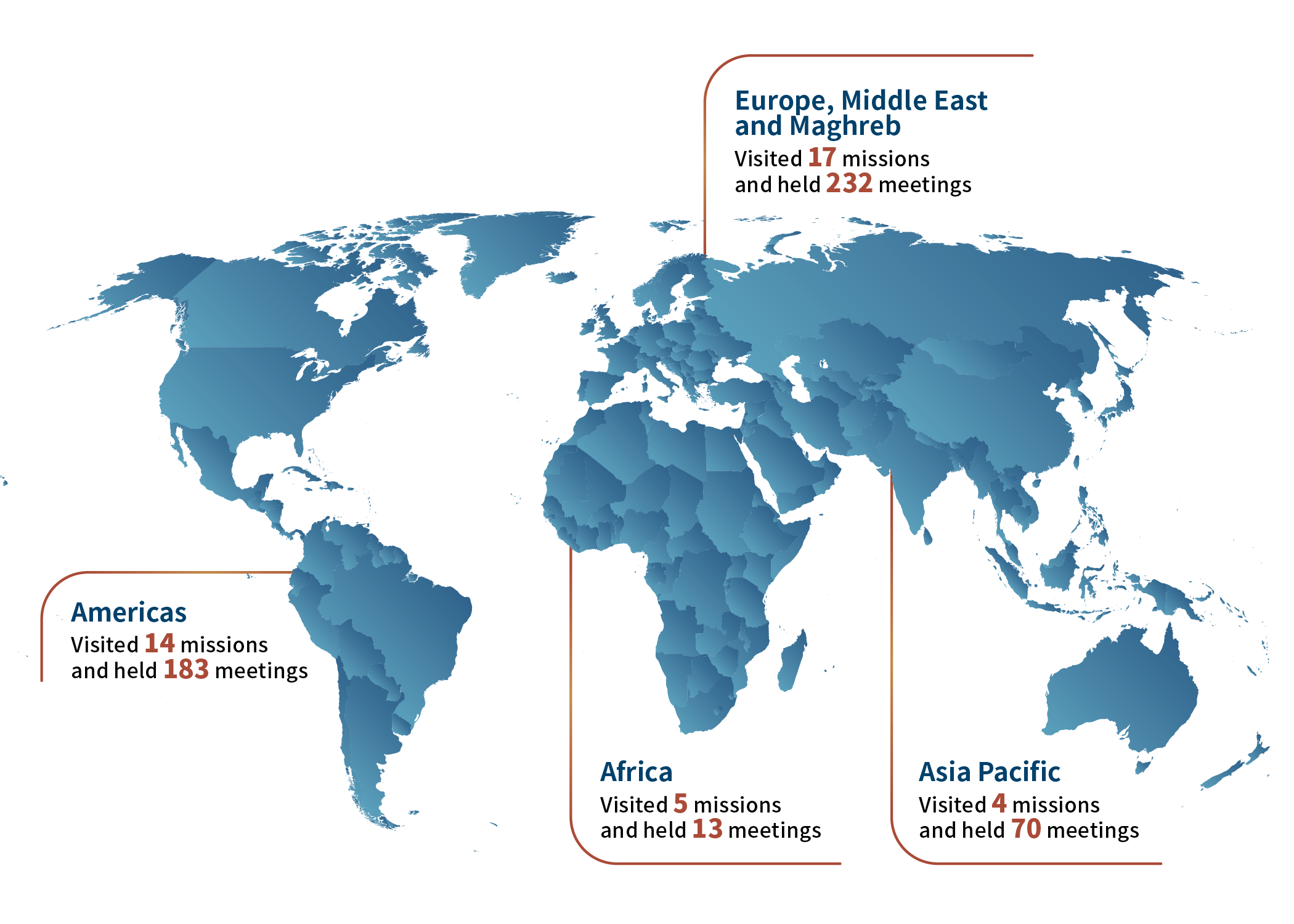

Sessions with visitors and teams also take place during visits to our missions. The Office of the Well-being Ombud only visits a mission when we are invited to do so. During the past fiscal year, our team members made:

- 14 visits to the Americas, where we met with you in 183 sessions

- 17 visits to Europe, Middle East (ME) and Maghreb, where we met with you in 232 sessions

- 4 visits to the Asia-Pacific region, where we met with you in 70 sessions

- 5 visits to Africa, where we met with you in 13 sessions

Text version

- 14 visits to the Americas, where we met with you in 183 sessions

- 17 visits to Europe, Middle East (ME) and Maghreb, where we met with you in 232 sessions

- 4 visits to the Asia-Pacific region, where we met with you in 70 sessions

- 5 visits to Africa, where we met with you in 13 sessions

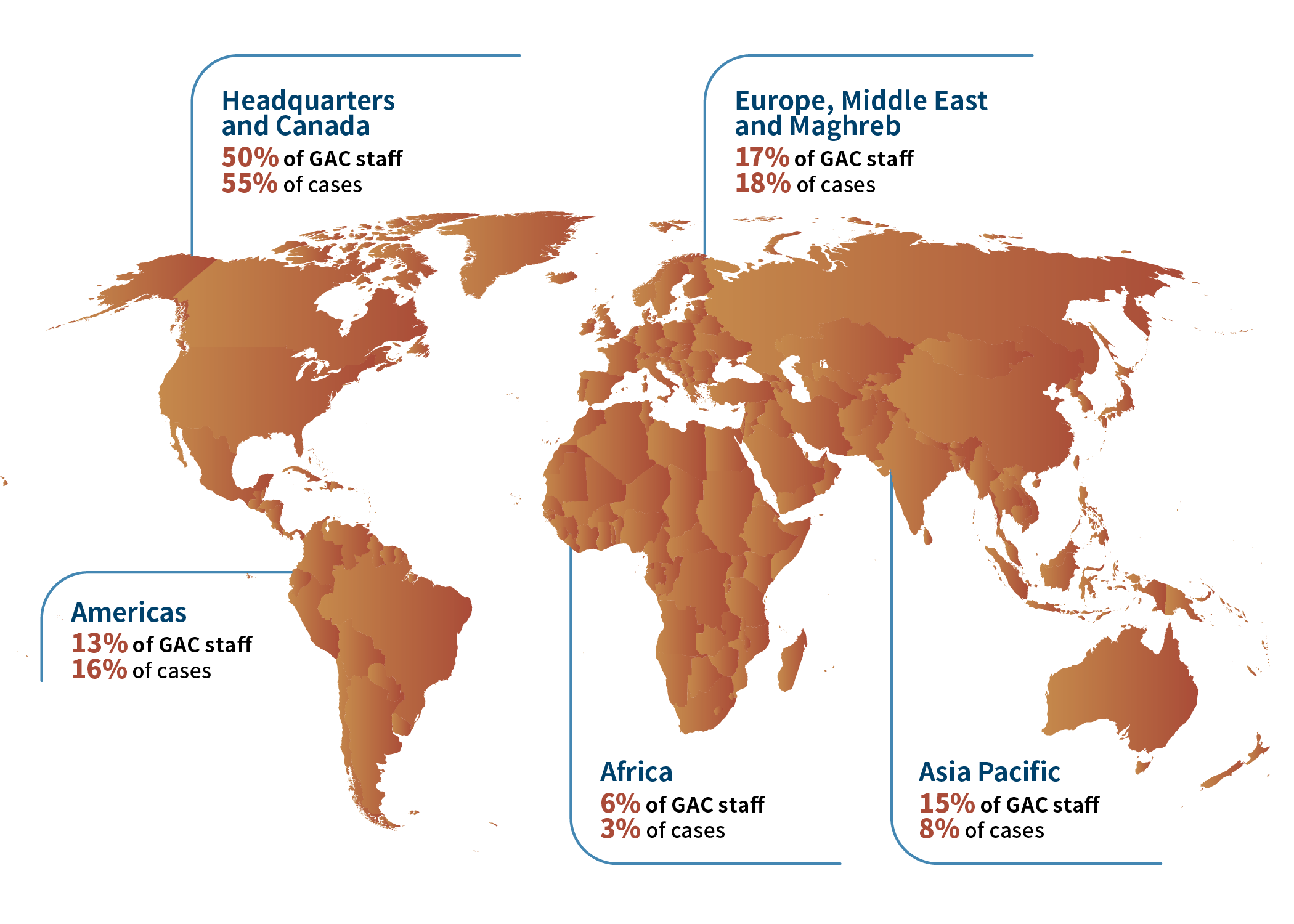

Our visitors: Where they work

Most of our interactions (55%) were with visitors at HQ and across Canada. The remaining 45% of our interactions were with our missions abroad: Americas (16%); Europe, Middle East (ME) and Maghreb (18%); Africa (3%); and Asia-Pacific (8%). These percentages closely correspond to the percentage of staff working in these regions, based on human resources demographics on the percentage of GAC employees in each region. For example, 13% of GAC’s employees work in the Americas and the Americas represented 16% of our cases in 2023 to 2024.

Text version

HQ + Canada

- 50% of GAC staff

- 55% of cases

Americas

- 13% of GAC staff

- 16% of cases

Europe, Middle East & Maghreb

- 17% of GAC staff

- 18% of cases

Africa

- 6% of GAC staff

- 3% of cases

Asia-Pacific

- 15% of GAC staff

- 8% of cases

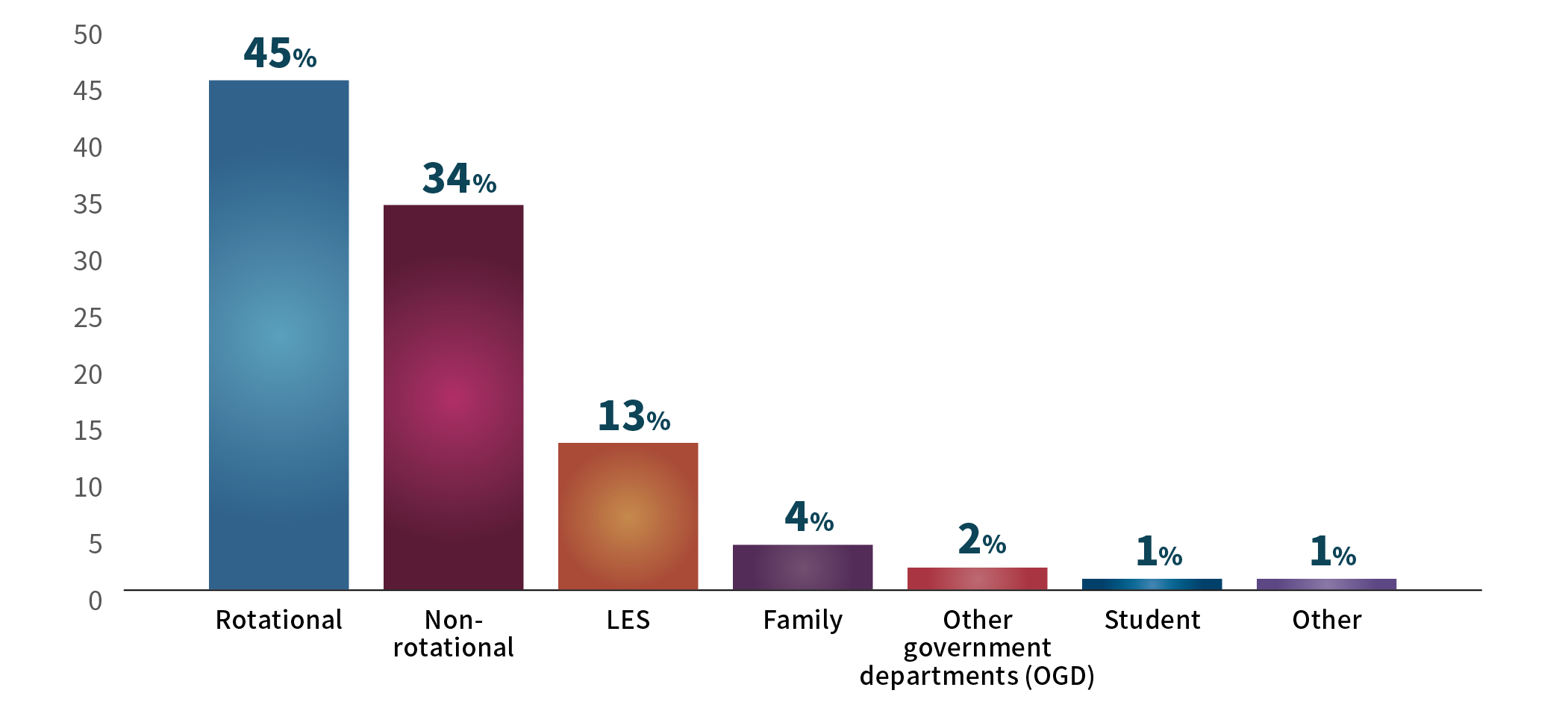

Our visitors: Who they are

Below you will find the general profile of our visitors. In the context of GAC’s human-resources demographics, LES, who are 40% of GAC employees, account for 13% of our cases, while CBS, who are 60% of GAC employees, account for 79% of our cases (45% + 34%). GAC is responsible for CBS and LES at Canadian missions around the world, and this duty of care also applies to Canadian staff from other government departments. Our services are available to all mission staff regardless of government department—even if your home department has its own ombud office.

Text version

Who are our visitors

Rotational: 45%

Non-rotational: 34%

LES: 13%

Family: 4%

Other government departments (OGD): 2%

Other: 1%

Student: 1%

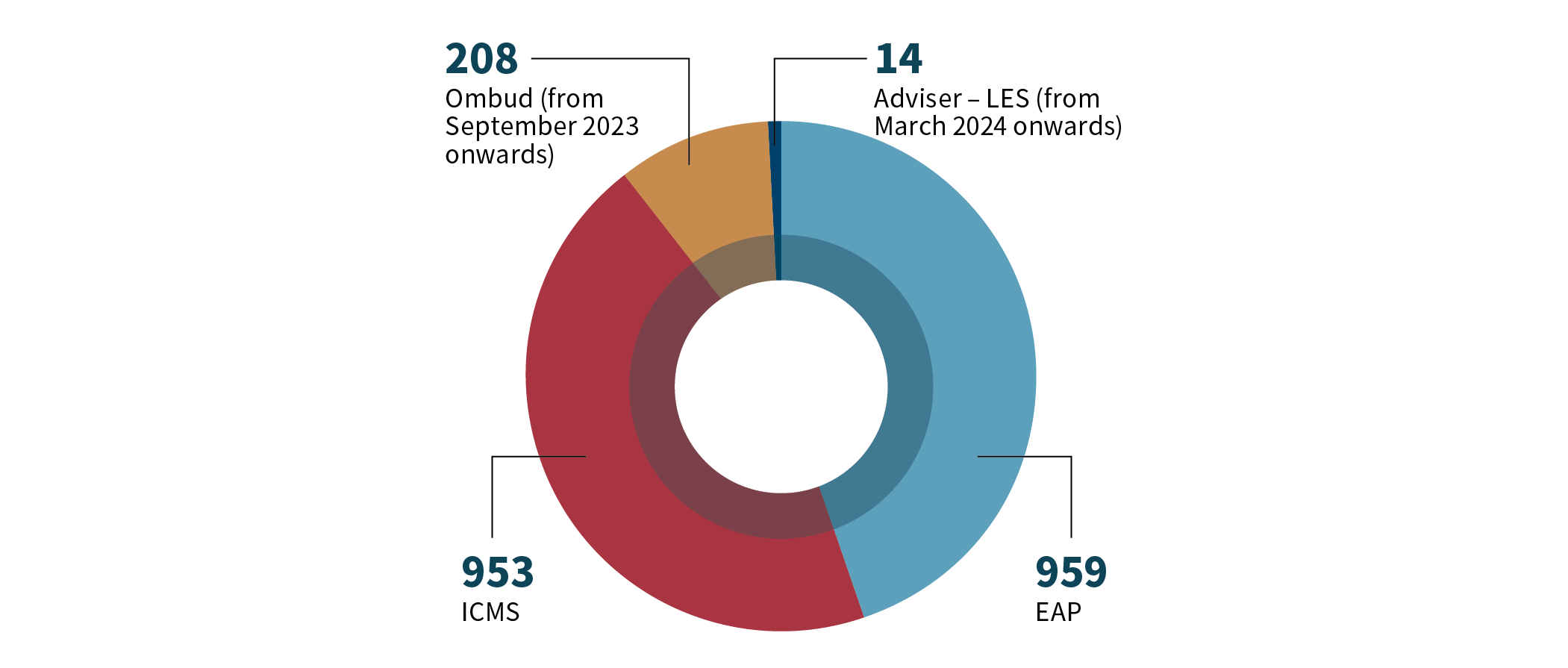

When a visitor reaches out to us to raise a specific issue, we count this as a “case.” A case may involve multiple people and multiple sessions or services. Some sessions may last an hour, while others will last several hours over several days or weeks. In the past year, our office worked on 2,134 cases, broken down by service provided as follows:

- EAP: 959 cases

- ICMS: 953 cases

- Ombud: 208 cases (from September 2023 onwards)

- Adviser - LES: 14 cases (from March 2024 onwards)

Text version

In the past year, our office worked on 2,134 cases, broken down by service provided as follows:

- EAP: 959 cases

- ICMS: 953 cases

- Ombud: 208 cases (from September 2023 onwards)

- Adviser - LES: 14 cases (from March 2024 onwards)

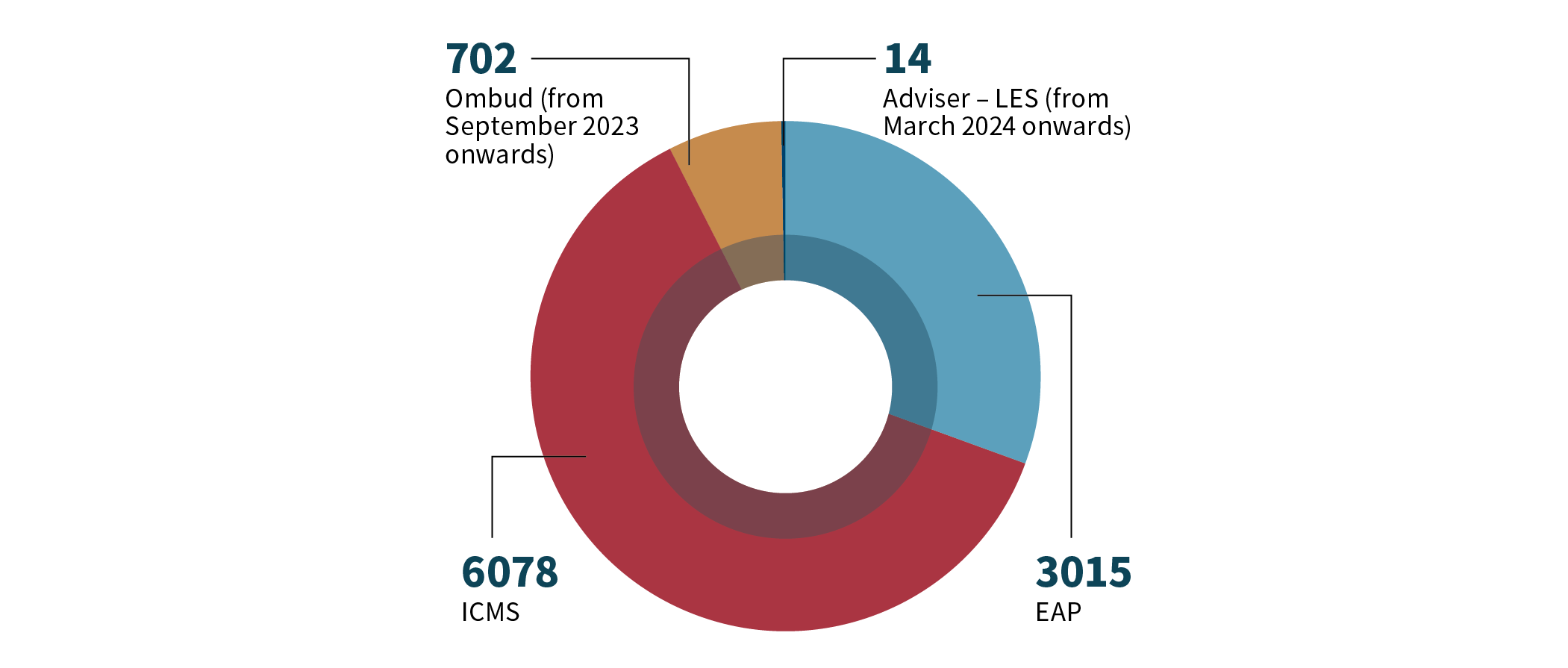

During these sessions, we met with the following total number of people:

- ICMS: 6,078

- EAP: 3,015

- Ombud: 702 (from September 2023 onwards)

- Adviser - LES: 14 (from March 2024 onwards)

Text version

During these sessions, we met with the following total number of people:

- ICMS: 6,078

- EAP: 3,015

- Ombud: 702 (from September 2023 onwards)

- Adviser - LES: 14 (from March 2024 onwards)

Our services: Types of sessions

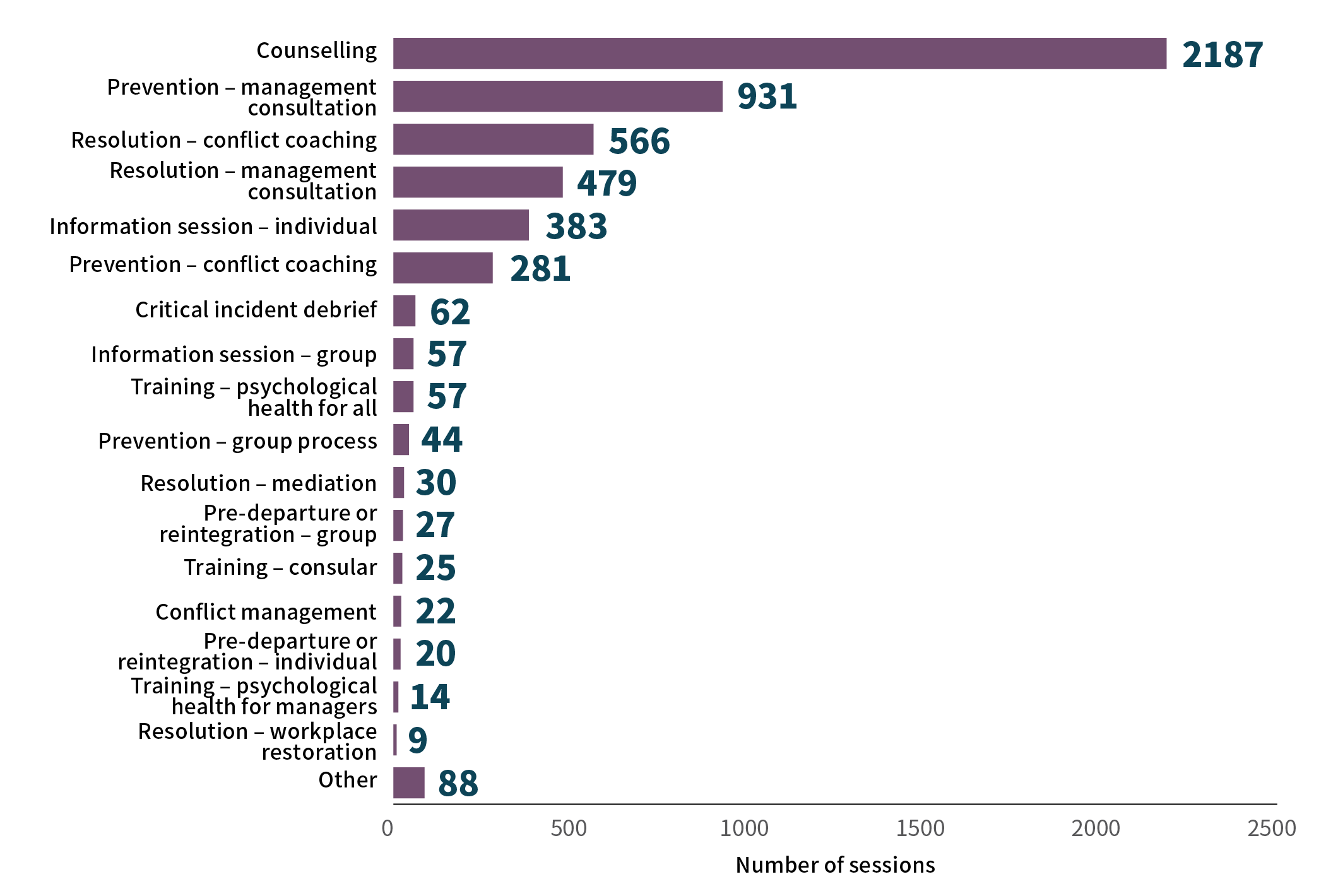

Breaking down the numbers further, the following chart shows the types of sessions that our office delivered. The most requested service by far was counselling (2,187), followed by management consultations focused on conflict prevention (931) and coaching focused on conflict resolution (566). In some sessions, we worked to raise awareness among managers about the impact of their management style on the psychological health and effectiveness of their employees and to help both managers and employees communicate issues respectfully to each other. Later in this report we discuss some of the most common issues affecting our visitors. Spoiler alert: management practices and psychological health were most frequently raised as the reasons for seeking counselling support.

Text version

Type of session

Other: 88

Resolution - workplace restoration: 9

Training - psychological health for managers: 14

Pre-departure or reintegration – individual: 20

Conflict management: 22

Training - consular: 25

Pre-departure or reintegration - group: 27

Resolution - mediation: 30

Prevention - group process: 44

Training - psychological health for all: 57

Information session - group: 57

Critical-incident debrief: 62

Prevention - conflict coaching: 281

Information session – individual: 383

Resolution - management consultation: 479

Resolution - conflict coaching : 566

Prevention - management consultation: 931

Counselling: 2,187

Your concerns

Your concerns 2023-2024

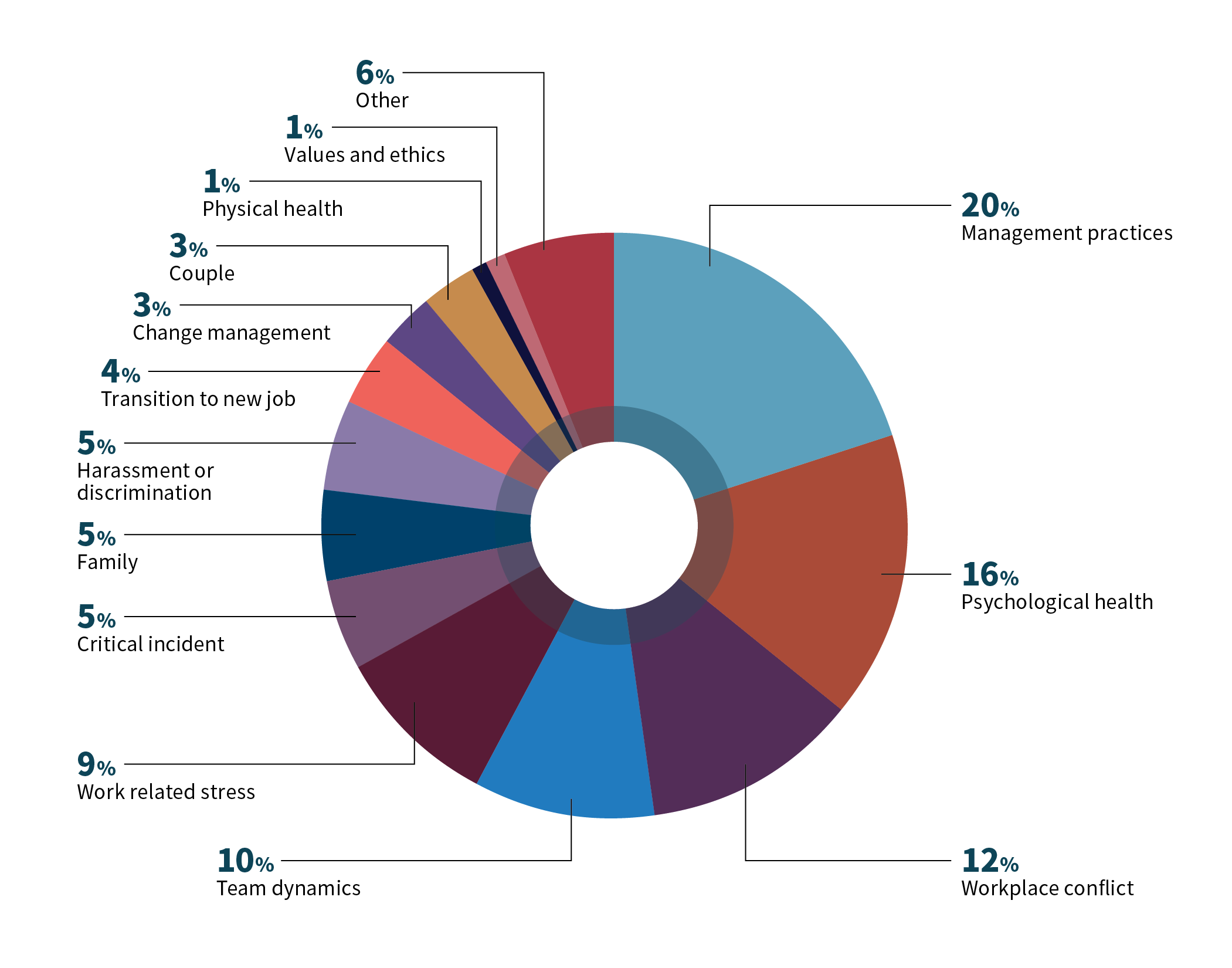

GAC is a complex organization with a complex mandate. This complexity has been linked to the need for culture change in our department. Importantly, our department has stated its commitment to a culture that focuses on its people. In this context, we have heard from employees about their changing expectations vis-à-vis management, especially when it comes to mental health, well-being and psychological safety at work. Over time we have also seen an increased focus on equity, diversity and inclusion—a focus that reflects societal changes and that has prompted questions about what respect and belonging in our workplaces looks like. In this part of the report, we talk about the issues and concerns that you have shared with us over the last year, as our department and our people navigated these complexities.

Some of the most common issues faced by our visitors this past year included:

- management practices such as uneven workload distribution and high expectations; performance management and feedback; the effects of physically returning to the office on manager-employee relationships and group dynamics

- psychological health problems ranging from anxiety and depression to bereavement and trauma

- conflicts in the workplace stemming from disputes among colleagues

- experiences of harassment or discrimination in the workplace

Importantly, you frequently raised with us the psychological consequences of crosscutting issues, including the impact the Middle East conflict has had on your well-being as well as your experiences confronting barriers to inclusion in the workplace.

Text version

The most common issues raised:

Management practices: 20%

Psychological health: 16%

Workplace conflict: 12%

Team dynamics: 10%

Work-related stress: 9%

Critical incident: 5%

Family: 5%

Harassment or discrimination: 5%

Transition to new job: 4%

Change management: 3%

Couple: 3%

Physical health: 1%

Values and ethics: 1%

Other: 6%

Management practices (20%)

Of all the visitors who came to us, 1 out of every 5 raised concerns about uneven workload distribution and high expectations, performance management and feedback loops, and telework and hybrid work arrangements.

- Uneven workload distribution and high expectations

One of the most common issues we heard about was a perceived incoherence and inequity in workload distribution. Employees described facing excessive tasks without the necessary resources or onboarding to navigate new assignments or new projects, which hindered their and their teams’ effectiveness. Employees regularly noted insufficient knowledge transfer or inadequate training, leading to performance problems that some said were made worse by the pressure of high-tempo environments. Managers described their own growing workloads, with some taking on additional responsibilities to support the work-life balance of their employees at the cost of their own well-being. Many employees stated that management expectations sometimes felt unreasonably high—leaving them discouraged. Some employees reported that setting boundaries on time spent working was perceived to be a risky move career-wise. Managers also reported feeling the heavier weight of expectations, describing more work with fewer resources, including the impacts of paying more attention to the psychological health of employees at a time when research tells us that several demographic groups are increasingly vulnerable to mental health issues.

- Performance management and feedback

Performance management discussions were described to us as a process fraught with worry and discomfort for both employees and managers. Employees regularly mentioned the stress associated with the public service performance management process and meetings with their supervisor. Further, employees consistently raised the absence of upward feedback mechanisms to flag concerns about their managers’ people management skills. At the same time, some managers told us about their attempts to engage in meaningful performance management that were resisted by employees. Whether the topic was a performance management process discussion or an upward feedback process, we heard how feedback about gaps in performance or behaviour felt threatening even when the intent was to provide a learning opportunity. What should have been an ongoing, constructive 2-way dialogue instead became a source of frustration for managers and employees. In some cases, these frustrations turned into conflicts—with some being resolved informally and others leading to formal complaints.

- Telework and hybrid work arrangements

The rise of telework and hybrid work arrangements presented both opportunities and challenges for individuals and for teams. Employees raised concerns about the potential inequities and inconsistencies in the application of these policies, including a lack of empathy for impacts on their health and their families. Managers also spoke to us of their increasing workloads, wherein office tasks, including administrative tasks and tasks requiring access to secure systems, were increasingly delegated upwards. We heard how these arrangements offer important flexibility. We also heard how they blur the boundaries between work and personal life, potentially affecting work-life balance, family dynamics and employee-manager relationships.

Psychological health (16%)

Psychological health is a big issue at work and the impact on our people cannot be overstated. You told us about the toll that psychological health issues take on your energy and productivity at work, and on your quality of life overall. The stigma surrounding psychological health challenges only served to exacerbate the problem. The fear of being judged by colleagues or managers prevented employees at all levels from opening up about their psychological health issues. Some visitors spoke of being too ashamed or too tired to ask for help. We also heard how psychological health issues in the workplace can create tension within teams and make it challenging for managers to foster a positive and supportive work culture.

- Challenges in addressing psychological health issues for managers

Managers are often on the front lines when it comes to dealing with psychological health issues in the workplace. They told us how they are expected to make sure that day-to-day operations run smoothly while also keeping an eye on their employees’ psychological health and well-being. This can be a daunting task, as managers do not always have the necessary tools to help people who are struggling. In some cases, they found themselves faced with situations requiring immediate intervention, such as suicidal thoughts or other mental-health crises. These can be overwhelming for even the most experienced manager. Managers told us that they don’t always have enough support to help with psychological health issues in the workplace and that programs like the EAP at GAC might not be enough.

In addition to the challenges of addressing psychological health in the workplace, managers must also navigate the ethical considerations that come with supporting their team members. Managers spoke of the delicate and difficult balance in working to ensure that they were respecting their employees’ privacy while also taking appropriate action to prioritize the well-being of their team members and the productivity of their teams.

Workplace conflicts (12%) and team dynamics (10%)

Interpersonal workplace conflicts can arise due to a range of reasons—from unclear expectations to differences in work styles, communication styles and personal values among team members. In your discussions with us you spoke about how these conflicts negatively affected team dynamics, productivity and the overall work environment. We continued to work with managers to help them to address conflicts promptly and to effectively support a psychologically healthy and productive work environment. At the same time, we worked with employees to identify strategies to manage challenging relationships and to raise difficult issues with their managers. We found that the following issues were recurring triggers of conflict: performance management, abuse of power, unrealistic expectations, unclear roles and responsibilities, and decisions following accommodation requests.

Team dynamics, whether at HQ or at missions, were strained for a number of reasons. We heard repeatedly how changes in management, whether in Canada or abroad, had an impact on teams, including complicating efforts to maintain cohesion and productivity. Some of you told us that changes, whether the arrival of new CBS at missions or the arrival of new team members at HQ, created an atmosphere of uncertainty, which led to misunderstandings over objectives, roles and responsibilities and to miscommunication and unclear work processes. Some employees felt that in planning for postings or promotions, their managers prioritized personal gains over team welfare, including by perpetuating a cycle of overwork that led to discontent and poor morale. At the same time, many of you spoke about rotationality as an opportunity for a refresh for individuals and for teams that may be stagnating or struggling.

Potentially traumatic event: Within the office we are increasingly referring to crises and critical incidents as “potentially traumatic events,” which focuses our attention on the impacts of these events on our people. A potentially traumatic event refers to an experience that can cause psychological harm to an individual. These events may overwhelm a person’s coping abilities and result in trauma symptoms like intrusive thoughts, nightmares, anxiety or avoidance behaviours. It’s important to note that not everyone exposed to such events will develop trauma; factors like resilience, social support and coping styles also influence an event’s impact on an individual. Providing adequate psychological preparation and resources for CBS and LES employees helps employees to heal and build resilience while minimizing disruptions to work.

Harassment or discrimination in the workplace (5%)

While a relatively small percentage of issues raised with us were primarily about harassment or discrimination, the impact of these experiences on you was serious. You described repercussions for your well-being, your sense of psychological safety and your ability to effectively contribute at work. You noted that the apparent absence of consequences for harmful behaviours seemed to tell everyone that it was fine to behave that way.

Some of you reached out to us when you were trying to decide what to do about harassment in the workplace. You spoke of a fear of reprisal that prevented you from reporting harassment and a concern about management inaction that could further perpetuate a culture of silence and complicity. Both complainants and respondents seeking a safe space in formal harassment investigations told us about feeling helpless, distressed and alone because of process-related delays and a lack of information on the steps and timelines related to formal processes and on where to go for advice and support.

Among the causes of harassment described to us were power dynamics within our organization. We heard how some individuals with authority, whether formal (based on their position) or informal (based on their identity or status) may feel tempted to mistreat other people, without fear of consequences. LES often reported feeling particularly vulnerable in this regard with respect to their CBS or LES supervisor or when societal power dynamics are mirrored at the mission. Harassment also happened in the context of bias and discrimination against certain identifiable groups, including women, people who are racialized, Indigenous people, people with disabilities and members of the LGBTQ2+ community. We heard from you about how these experiences made you feel unsafe and unwelcome at work.

Notably, over the course of the reporting period we heard from you that the department’s efforts to address harassment are producing positive change, including in the area of accountability. And more of you reached out to us in the hope that informal or formal resolutions to experiences of harassment were possible.

Harassment and discrimination do not happen in isolation. They are often intertwined with other issues, including the mental health struggles of some of those engaging in harassing behaviours. Visitors told us that experiencing harassment or discrimination had impacts on their psychological health or that their mistreatment was a symptom of a larger issue related to a conflict with a colleague. Considering the above, experiences of harassment or discrimination may fall under the broader categories of psychological health or workplace conflict, rather than being counted primarily under the narrower category of harassment or discrimination.

Crosscutting issues: Crisis and the consequences for employee well-being

The nature of GAC’s mandate means that our people are literally on the front lines of crises as they are unfolding. This year, we observed remarkable resilience in the face of extreme demands. We heard from employees and managers alike that they moved from crisis to crisis with little respite or reprieve. During the year you told us time and again that we as a department tend to lean on the same individuals to respond in an emergency, potentially leading to burnout and diminished well-being. We have seen that, for some, the aftermath of harrowing incidents becomes a potential trigger for symptoms of post-traumatic stress.

Crises not only increase workloads but also shape the realities of the workplace, adding a layer of unpredictability and urgency to daily operations and surfacing tensions and emotions that can lead to stress and conflict. Once the crisis passed, we observed lasting impacts on people that continued to affect their lives at work and at home. In 2023 to 2024 we saw once again how our global mandate makes tough demands on our people. We have seen how after such events employees may feel a strong need to discuss the event, struggle to focus on work, and worry about safety for themselves and their families. From conflict in Sudan to evacuations from Haiti, our employees around the world coped with the professional and personal impacts of global events. In autumn 2023 we saw a period of acute polycrisis, which included the reduction of our footprint in India and violence and conflict in the Middle East—all of which resulted in increased workloads and profound psychological impacts on employees.

The violence and conflict in the Middle East affected you deeply, in different ways. You told us about people you know who were injured or killed. You spoke to us of your personal grief but also struggles in the workplace, regardless of your community connections and regardless of whether you worked on these issues or not. For many employees, the present conflict brought to the forefront feelings ranging from discomfort to serious distress; for others, a clash between personal experiences, beliefs and values and the Departmental Values and Ethics Code. This led to anxiety, fear and frustration. Many of you sought out our help either individually or collectively to organize safe spaces where you could speak freely without worrying about judgments or career consequences. Many of you also spoke of wanting a department-wide dissent channel through which you could provide your policy advice, personal views and opinions without fear.

Leadership during crisis

In times of crisis, we heard from employees who felt sad, overwhelmed and stressed. We saw how managers, by putting in place proactive measures to support their teams, could help prevent burnout and ensure that employees were able to perform at their best even in the face of adversity. We saw important examples of compassion, but also situations where managers were unable or unwilling to create opportunities for open communication or offer flexibility in work arrangements to accommodate employee needs. In times of crisis, employees spoke of a lack of transparency in decision making, limited access to the tools and information they needed to effectively do their work, and a lack of responsiveness when the issue of workplace or personal stress was raised.

Crosscutting issues: Barriers to inclusion

We see a deep commitment by so many across GAC to diversity, inclusion and reconciliation. But many of you also described for us hurtful, hateful and unacceptable experiences at work because of who you are. You shared with us experiences of racism, homophobia, antisemitism, Islamophobia, ablism, harassment, discrimination and microaggressions. Some of you described “invisible disabilities” and dealing with challenges that others can’t always see or don’t always understand, which made you feel excluded. Many employees and managers are working hard to make inclusion a reality at GAC, but important gaps and barriers persist.

In particular, employees with disabilities described ongoing battles to access the workplace and access the tools they need to do their work. People in our department with invisible disabilities described hesitating to disclose their needs due to fear of stigma, potential career repercussions, or a perceived lack of understanding from colleagues and supervisors. We have heard from neurodivergent employees for whom their reality in the workplace included an often-daily struggle to advocate for themselves. The reluctance to disclose a disability prevented some individuals from accessing necessary accommodations and support services. Through our conversations we heard how asking for accommodations at work can be difficult. We’ve heard from employees who are afraid to ask for an accommodation because they don’t want to be treated differently or because they must deal with a lot of red tape. This can make a difficult job situation even more stressful for employees.

We heard about a persistent lack of belonging for some employees. Some described feeling looked down upon by peers who have a different professional or educational background. Others described experiences with persistent microaggressions in the workplace based on how they looked or assumptions about their background or identity. Indigenous employees spoke to us of the absence of respect in the workplace despite stated commitments to reconciliation. We heard from racialized and visible-minority employees of efforts at inclusion that stopped short of creating a sense of real belonging. The impact of gender dynamics on teams featured in some of our conversations. You told us of situations where diversity in representation was encouraged but diversity in thought was not.

Family life also made it hard for some people to feel like they were really part of the team at work. You described how situations like taking care of family or not having support from your family for your career choices affected how well you were able to do your job and whether you felt like you belonged.

We heard from newer members of the department who spoke of struggling to find their place within existing cliques that seemed impenetrable.

Language was described as a barrier to inclusion. Francophone employees told us that when key discussions happen only in English, they feel marginalized. Performance management discussions conducted solely in English created feelings of exclusion and hindered effective communication and career development opportunities.

These experiences affected your psychological health and contributed to feelings of exclusion and a lack of team cohesion.

Spotlight on locally engaged staff

Of our visitors this year, 13% were LES. We know that many LES hesitate to reach out to us. Some are unfamiliar with what an ombud does and may be wary of our ability to help, and they fear reprisal if confidentiality is broken. We hope that as LES get to know us, including through this report, more will feel comfortable speaking to us. We are encouraged by those LES who do reach out—some of whom are doing so on behalf of their colleagues—and the role they play in helping the LES community feel more comfortable in seeking support and in feeling safer to pursue action, whether formal or informal.

From LES we hear how they feel vulnerable to abuses of power—sometimes by CBS, sometimes by other LES, sometimes because of local cultural dynamics or because of more complex intercultural dynamics. There is a feeling that inappropriate behaviours can remain invisible to Headquarters because of geographic distance. Some LES spoke about a feeling of powerlessness because LES are unrepresented and subject to terms and conditions of employment that vary from country to country. We have heard from LES who cannot afford to lose their jobs and so decide to remain silent about their experiences because they fear repercussions for their employment. The fear of reprisal is particularly difficult to manage for an LES employee who wants to file a grievance about their head of mission (HOM) but is hesitant to do so because of grievance processes where their HOM is the final decision maker.

LES have openly asked us, “Do we matter?” We have heard how this feels most acute in international crisis situations when CBS are evacuated, leaving behind a perception among LES that they are being abandoned. We were told that the absence of meaningful inclusion and transparent communications created a culture of mistrust, particularly among those for whom English or French is not their first language. This has resulted in a lack of understanding of the policies and guidelines that affect their daily lives.

Spotlight on rotational families

The nature of GAC’s work presents unique challenges and extraordinary opportunities for our families. Navigating assignments abroad can be a tumultuous journey, not just for employees, but for our families too. When a posting happens, employees and family members adjust to new roles. For families separated during a posting—which might include a non-accompanying spouse, an adult child or aging parent, for example—the emotional stress of separation is felt by all, including employees. Accessing mental health support can be particularly challenging for CBS employees working abroad or returning home. At post CBS employees face unfamiliar health-care systems and language and cultural barriers, and may be prevented from accessing support in their home province due to provincial residency requirements. After an absence from Canada, CBS and their families returning to Canada may struggle to find family doctors or specialists.

We spoke with family members, including dependent children as young as 14, and they told us of the very real emotional and psychological challenges they face. Adjusting to new environments, schools and social dynamics—often leaving behind familiar settings and loved ones—is hard. Factors such as cultural adjustment, isolation from support networks and the demands of the assignment itself contributed to stress and strain on relationships. Accompanying spouses and partners are critical to the success of overseas assignments, yet they frequently told us of feeling undervalued and underappreciated. From pre-departure formalities to settling in at post, accompanying spouses are often excluded from these administrative processes, leading to heightened stress and conflict. Situations ranging from high interpersonal tension to domestic violence are often kept silent. For accompanying spouses and partners, the connection to Canada is often through the CBS employee and seeking support can feel more distant and daunting in times when they most need the support.

We have consistently heard how the challenges are especially acute in hardship postings, including unaccompanied posts where families may have to be divided, and posted employees function in high-stress and high-risk environments without their traditional sources of emotional support.

Returning home post-assignment brings its own set of challenges, sometimes leading to feelings of loneliness and displacement and the need to readjust to what used to be familiar surroundings.

The administration of foreign service directives (FSDs) was frequently raised with us as a source of stress for families. Many employees on posting expressed frustrations about what they perceive to be the inflexible application of certain FSDs, especially those in very high-risk missions or when there has been a mandatory evacuation of employees or family members. We have heard how the administrative burden of FSDs, including delays in processing claims, was a source of stress and, in some cases, financial hardship.

MSH International insurance

Because of gaps in coverage due to delays in approvals and claims processing by MSH International, CBS and their families were faced with a range of issues. These included problems related to general stress, well-being and their overall health, as well as significant financial hardship. We heard from CBS carrying tens of thousands of dollars of debt. At the same time, CBS told us that they were forgoing or postponing medical visits for fear of the financial costs and that they lived in constant fear of potential medical emergencies. While acknowledging GAC’s efforts to make no-interest loans available to cover costs, some of you told us that you would avoid postings until the situation was resolved, resulting in a loss of talent for GAC at our missions abroad.

Looking ahead

Our deputy ministers have referred to the Office of the Well-being Ombud and Inspector General as your first port of call when you are confronting a difficult situation. For many of you, we have been just that. During our discussions with you, we have attempted to provide sound guidance and a range of options that can make your situation a little bit better. We have continued to learn more about what you need. We are building the capacity of our office to better serve you and our department and to more meaningfully improve work environments across GAC.

In addition to providing individual and team support, the office this year offered input into systemic responses. These included backing for formal decompression programs for some of our most vulnerable posts and key training for employees facing specific psychological risks due to their work. This includes those working on complex consular cases. Our office continues to expand to meet the growing demand for our services, including by bringing on board new counsellors and conflict-management practitioners and introducing feedback loops on our own work so that we can continue to improve and learn.

Our team has deep experience in the field of intercultural understanding, including through work with our missions around the world. We take seriously the feedback we’ve received that some employees are not comfortable reaching out to us because, for example, we do not as a team reflect their lived experiences. We are continuing to build a more diverse team and expand our knowledge and skills to ensure our work is inclusive and fosters belonging. We are committed to doing better and will continue to identify resources to meet the diverse needs of GAC employees.

We are also building our data analytics capacity with a view to allowing us to provide better insight to support departmental well-being efforts and to get more feedback from you. With a new data tracking system, we will be able to protect confidentiality while enhancing our ability to capture in finer detail the issues that you face. In turn, we will be able to produce reports that contain more helpful data analysis. We are also working on future reports to spotlight specific issues.

In the coming year, we will continue to pay attention to crosscutting issues that you raise with us. These include new guidelines on in-office presence, the impacts of transformation and reorganization, the updates to the Values and Ethics Code for the Public Service, the Departmental Values and Ethics Code and the Code of Conduct for Canadian Representatives Abroad.

Looking ahead, GAC will continue to make important strides in its commitment to a more inclusive, transparent and accountable workplace a reality. Important milestones such as the Annual Report on Misconduct and Wrongdoing at Global Affairs Canada, the accessibility plan, the second iteration of the Deputy Ministers’ Sponsorship Program and a new initiative to introduce talent management for non-executives are key steps to building a healthier workplace for all. That said, there is much work to be done and the office remains committed to doing its part.

Contact us

If you need support from the Office of the Well-being Ombud and Inspector General, please send an email to ombud@international.gc.ca. Our services are offered to all Canada-based staff wherever they work, their dependents and locally engaged staff. We also offer certain services to employees of other government departments working at our missions abroad.

The team (2023-2024)

Ayesha Rekhi

Well-being Ombud and Inspector General

Daniel Campeau

Deputy Ombud

Tejumo Ogouma

Deputy Director, Informal Conflict Management

Alain Caron

Informal Conflict Resolution Practitioner

Mathieu ChampRoux

Informal Conflict Resolution Practitioner

Melanie Brousseau

Informal Conflict Resolution Practitioner

Noufoh Nadjombe

Informal Conflict Resolution Practitioner

Tanya Prévost

Informal Conflict Resolution Practitioner

Joanna Ignaszewska

Acting Deputy Director and Counsellor, Employee Assistance Program

Brigitte Cadieux

Employee Assistance Program Counsellor

Lyne Bouffard

Employee Assistance Program Counsellor

Martine Parent

Employee Assistance Program Counsellor

Jean Ducharme

Deputy Director, Analysis & Outreach

Irene Abou Hamad

Adviser (LES)

Pauline Seto

Analyst

Sabrina Abud-Lapierre

Intake and Outreach Officer

Caroline Audet

Senior Adviser and Acting Deputy Director

Birgit Copeland

Executive Assistant

Claude Lanthier

Administrative Assistant

Annex

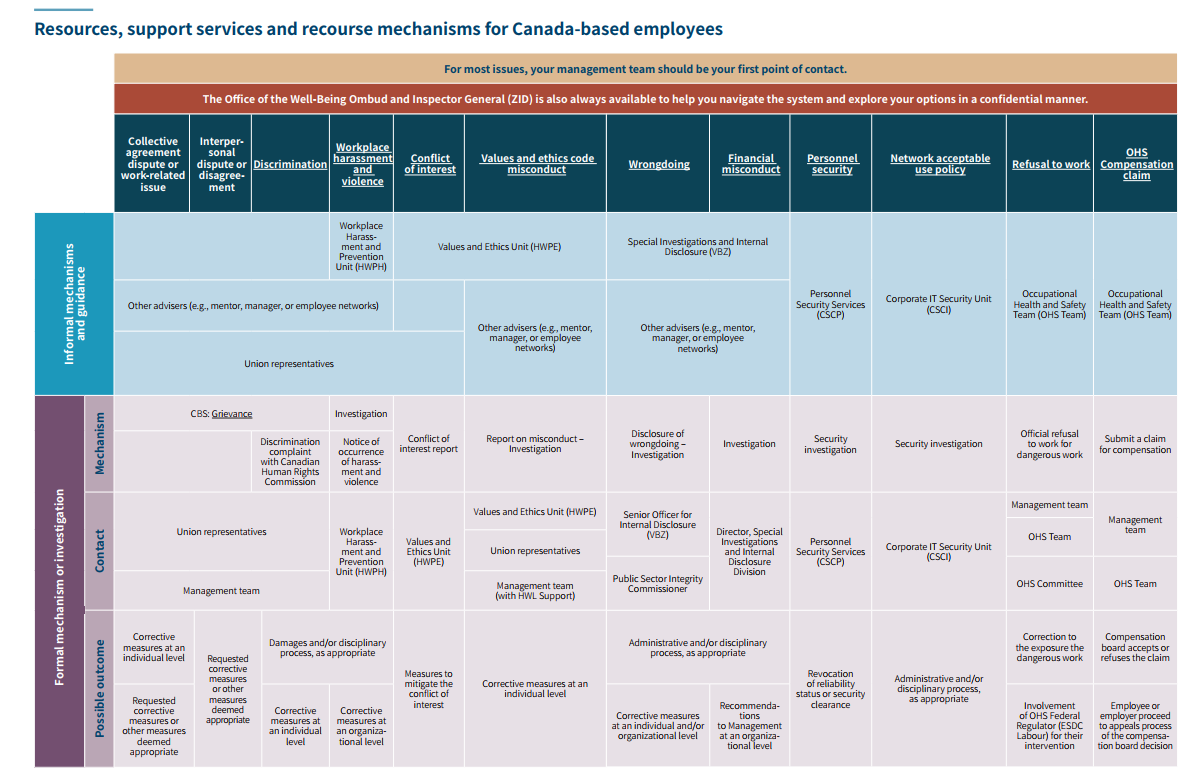

Resources, support services and recourse mechanisms for Canada-based employees

Text version

Resources, support services and recourse mechanisms for Canada-based employees

Many resources, support services, and recourse mechanisms that help maintain a respectful, healthy and inclusive work environment are available. The following table presents some of these resources to help employees navigate the system. We encourage employees to use the links and contacts below to find further information.

For most issues, your management team should be your first point of contact.

The Office of the Well-Being Ombud and Inspector General (ZID) is also always available to help you navigate the system and explore your options in a confidential manner.

Collective agreement dispute or work-related issue

Informal mechanisms and guidance

- Office of the Well-being Ombud and Inspector General

- Other advisers (e.g., mentor, manager, or employee networks)

- Union representatives

Formal mechanism or investigation

Mechanism

- CBS: Grievance

Contact

- Union representatives

- Management team

Possible outcome

- Corrective measures at an individual level

- Requested corrective measures or other measures deemed appropriate

Interpersonal dispute or disagreement

Informal mechanisms and guidance

- Office of the Well-being Ombud and Inspector General

- Other advisers (e.g., mentor, manager, or employee networks)

- Union representatives

Formal mechanism or investigation

Mechanism

- CBS: Grievance

Contact

- Union representatives

- Management team

Possible outcome

- Requested corrective measures or other measures deemed appropriate

Discrimination

Informal mechanisms and guidance

- Office of the Well-being Ombud and Inspector General

- Other advisers (e.g., mentor, manager, or employee networks)

- Union representatives

Formal mechanism or investigation

Mechanism

- CBS: Grievance

- Discrimination complaint with Canadian Human Rights Commission

Contact

- Union representatives

- Management team

Possible outcome

- Damages and/or disciplinary process, as appropriate

- Corrective measures at an individual level

Workplace harassment and violence

Informal mechanisms and guidance

- Office of the Well-being Ombud and Inspector General

- Workplace Harassment and Prevention Unit (HWPH)

- Other advisers (e.g., mentor, manager, or employee networks)

- Union representatives

Formal mechanism or investigation

Mechanism

- Investigation

- Notice of occurrence of harassment and violence

Contact

Workplace Harassment and Prevention Unit (HWPH)

Possible outcome

- Damages and/or disciplinary process, as appropriate

- Corrective measures at an organizational level

Conflict of interest

Informal mechanisms and guidance

- Office of the Well-being Ombud and Inspector General

- Values and Ethics Unit (HWPE)

- Union representatives

Formal mechanism or investigation

Mechanism

- Conflict of interest report

Contact

Values and Ethics Unit (HWPE)

Possible outcome

- Measures to mitigate the conflict of interest

Values and ethics code misconduct

Informal mechanisms and guidance

- Office of the Well-being Ombud and Inspector General

- Values and Ethics Unit (HWPE)

- Other advisers (e.g., mentor, manager, or employee networks)

Formal mechanism or investigation

Mechanism

- Report on misconduct - Investigation

Contact

Values and Ethics Unit (HWPE)

- Union representatives

- Management team (with HWL Support)

Possible outcome

- Corrective measures at an individual level

Wrongdoing

Informal mechanisms and guidance

- Office of the Well-being Ombud and Inspector General

- Special Investigations and Internal Disclosure (VBZ)

- Other advisers (e.g., mentor, manager, or employee networks)

Formal mechanism or investigation

Mechanism

- Disclosure of wrongdoing - Investigation

Contact

Senior Officer for Internal Disclosure (VBZ)

- Public Sector Integrity Commissioner

Possible outcome

- Administrative and/or disciplinary process, as appropriate

- Corrective measures at an individual and/or organizational level

Financial misconduct

Informal mechanisms and guidance

- Office of the Well-being Ombud and Inspector General

- Special Investigations and Internal Disclosure (VBZ)

- Other advisers (e.g., mentor, manager, or employee networks)

Formal mechanism or investigation

Mechanism

- Investigation

Contact

Director, Special Investigations and Internal Disclosure Division

Possible outcome

- Administrative and/or disciplinary process, as appropriate

- Recommendations to Management at an organizational level

Personnel security

Informal mechanisms and guidance

- Office of the Well-being Ombud and Inspector General

- Personnel Security Services (CSCP)

Formal mechanism or investigation

Mechanism

- Security investigation

Contact

Personnel Security Services (CSCP)

Possible outcome

- Revocation of reliability status or security clearance

Network acceptable use policy

Informal mechanisms and guidance

- Office of the Well-being Ombud and Inspector General

- Corporate IT Security Unit (CSCI)

Formal mechanism or investigation

Mechanism

- Security investigation

Contact

- Corporate IT Security Unit (CSCI)

Possible outcome

- Administrative and/or disciplinary process, as appropriate

Refusal to work

Informal mechanisms and guidance

- Office of the Well-being Ombud and Inspector General

- Occupational Health and Safety Team (OHS Team)

Formal mechanism or investigation

Mechanism

- Official refusal to work for dangerous work

Contact

- Management team

- OHS Team

- OHS Committee

Possible outcome

- Correction to the exposure to dangerous work

- Involvement of OHS Federal Regulator (ESDC Labour) for their intervention

OHS compensation claim

Informal mechanisms and guidance

- Office of the Well-being Ombud and Inspector General

- Occupational Health and Safety Team (OHS team)

Formal mechanism or investigation

Mechanism

- Submit a claim for compensation

Contact

- Management team

- OHS Team

Possible outcome

- Compensation board accepts or refuses the claim

- Employee or employer proceed to appeals process of the compensation board decision

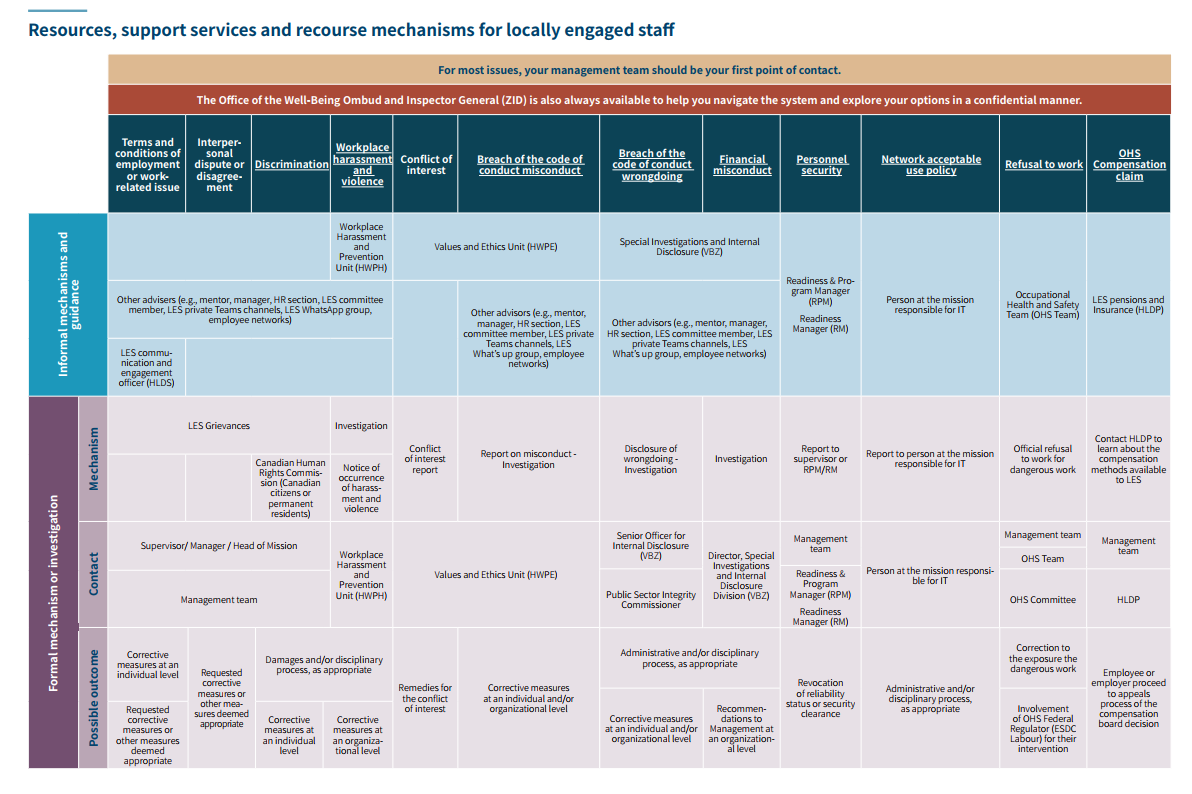

Resources, support services and recourse mechanisms for locally engaged staff

Text version

Resources, support services and recourse mechanisms for locally engaged staff

For most issues, your management team should be your first point of contact.

The Office of the Well-Being Ombud and Inspector General (ZID) is also always available to help you navigate the system and explore your options in a confidential manner.

Terms and conditions of employment or work-related issue

Informal mechanisms and guidance

- Office of the Well-being Ombud and Inspector General

- Other advisers (e.g., mentor, manager, HR section, LES committee member, LES private Teams channel, LES WhatsApp group, employee networks)

- LES communication and engagement officer (HLDS)

Formal mechanism or investigation

Mechanism

- LES Grievances

Contact

- Supervisor / Manager / Head of Mission

- Management team

Possible outcome

- Corrective measures at an individual level

- Requested corrective measures or other measures deemed appropriate

Interpersonal dispute or disagreement

Informal mechanisms and guidance

- Office of the Well-being Ombud and Inspector General

- Other advisers (e.g., mentor, manager, HR section, LES committee member, LES private Teams channel, LES WhatsApp group, employee networks)

Formal mechanism or investigation

Mechanism

- LES Grievances

Contact

- Supervisor / Manager / Head of Mission

- Management team

Possible outcome

- Requested corrective measures or other measures deemed appropriate

Discrimination

Informal mechanisms and guidance

- Office of the Well-being Ombud and Inspector General

- Other advisers (e.g., mentor, manager, HR section, LES committee member, LES private Teams channel, LES WhatsApp group, employee networks)

Formal mechanism or investigation

Mechanism

- LES Grievances

- Canadian Human Rights Commission (Canadian citizens or permanent residents)

Contact

- Supervisor / Manager / Head of Mission

- Management team

Possible outcome

- Damages and/or disciplinary process, as appropriate

- Corrective measures at an individual level

Workplace harassment and violence

Informal mechanisms and guidance

- Office of the Well-being Ombud and Inspector General

- Workplace Harassment and Prevention Unit (HWPH)

- Other advisers (e.g., mentor, manager, HR section, LES committee member, LES private Teams channel, LES WhatsApp group, employee networks)

Formal mechanism or investigation

Mechanism

- Investigation

- Notice of occurrence of harassment and violence

Contact

Workplace Harassment and Prevention Unit (HWPH)

Possible outcome

- Damages and/or disciplinary process, as appropriate

- Corrective measures at an organizational level

Conflict of interest

Informal mechanisms and guidance

- Office of the Well-being Ombud and Inspector General

- Values and Ethics Unit (HWPE)

Formal mechanism or investigation

Mechanism

- Conflict of interest report

Contact

Values and Ethics Unit (HWPE)

Possible outcome

- Remedies for the conflict of interest

Breach of the code of conduct misconduct

Informal mechanisms and guidance

- Office of the Well-being Ombud and Inspector General

- Values and Ethics Unit (HWPE)

- Other advisers (e.g., mentor, manager, HR section, LES committee member, LES private Teams channel, LES WhatsApp group, employee networks)

Formal mechanism or investigation

Mechanism

- Report on misconduct - Investigation

Contact

Values and Ethics Unit (HWPE)

Possible outcome

- Corrective measures at an individual and/or organizational level

Breach of the code of conduct wrongdoing

Informal mechanisms and guidance

- Office of the Well-being Ombud and Inspector General

- Special Investigations and Internal Disclosure (VBZ)

- Other advisers (e.g., mentor, manager, HR section, LES committee member, LES private Teams channel, LES WhatsApp group, employee networks)

Formal mechanism or investigation

Mechanism

- Disclosure of wrongdoing - Investigation

Contact

Senior Officer for Internal Disclosure (VBZ)

- Public Sector Integrity Commissioner

Possible outcome

- Administrative and/or disciplinary process, as appropriate

- Corrective measures at an individual and/or organizational level

Financial misconduct

Informal mechanisms and guidance

- Office of the Well-being Ombud and Inspector General

- Special Investigations and Internal Disclosure (VBZ)

- Other advisers (e.g., mentor, manager, HR section, LES committee member, LES private Teams channel, LES WhatsApp group, employee networks)

Formal mechanism or investigation

Mechanism

- Investigation

Contact

Director, Special Investigations and Internal Disclosure Division (VBZ)

Possible outcome

- Administrative and/or disciplinary process, as appropriate

- Recommendations to Management at an organizational level

Personnel security

Informal mechanisms and guidance

- Office of the Well-being Ombud and Inspector General

- Readiness & program manager (RPM)

- Readiness manager (RM)

Formal mechanism or investigation

Mechanism

- Report to supervisor or RPM/RM

Contact

Management team

- Readiness & program manager (RPM)

- Readiness manager (RM)

Possible outcome

- Administrative and/or disciplinary process, as appropriate

- Recommendations to Management at an organizational level

Network Acceptable Use Policy

Informal mechanisms and guidance

- Office of the Well-being Ombud and Inspector General

- Person at the mission responsible for IT

Formal mechanism or investigation

Mechanism

- Report to person at the mission responsible for IT

Contact

- Person at the mission responsible for IT

Possible outcome

- Revocation of reliability status or security clearance

- Administrative and/or disciplinary process, as appropriate

Refusal to work

Informal mechanisms and guidance

- Office of the Well-being Ombud and Inspector General

- Occupational Health and Safety Team (OHS Team)

Formal mechanism or investigation

Mechanism

- Official refusal to work for dangerous work

Contact

- Management team

- OHS Team

- OHS Committee

Possible outcome

- Correction to the exposure to dangerous work

- Involvement of OHS Federal Regulator (ESDC Labour) for their intervention

OHS Compensation claim

Informal mechanisms and guidance

- Office of the Well-being Ombud and Inspector General

- LES pensions and insurance (HLDP)

Formal mechanism or investigation

Mechanism

- Contact HLDP to learn about the compensation methods available to LES

Contact

- Management team

- HLDP

Possible outcome

- Employee or employer proceed to appeals process of the compensation board decision

- Date modified: