A Global Crisis Requires a Global Response – Report by Hon Bob Rae, Special Envoy of Prime Minister of Canada on Humanitarian and Refugee Issues

This report reflects my conclusions as Special Envoy of Prime Minister Trudeau on Humanitarian and Refugee Issues, an assignment which began in early 2020 and concludes at the end of July in the same year. I have been greatly assisted in this task by officials working for the government of Canada, numerous academics, aid officials, commentators, refugee leaders and experts worldwide. I have also had the opportunity to meet, both in this work and my earlier work reporting on the Rohingya crisis, refugees and citizens of host countries whose lived experiences have influenced me greatly in my thinking. I am grateful for their generosity in welcoming me into their homes and communities, and for sharing so freely the circumstances of their lives.

Table of contents

Why a global response?

The thrust of my report is stated in its title. The crisis the world is facing is truly global in its implications. The response to it must be at once local, national, and global. Anything less will be inadequate. I was asked to report to the Prime Minister of Canada on the rapidly growing number of displaced people in the world, the impact this was having on both host and donor countries, and its implications for Canada and Canadians. This invitation came before the impact of COVID-19 was fully apparent, and, needless to say, COVID-19 has had a deep impact on the depth and gravity of the crisis.

There are many arguments being made as to why responding to the COVID-19 crisis at the global level should be a lower priority for Canada and other countries. With the unprecedented level of unemployment, underemployment, personal and corporate bankruptcies, the financial crisis affecting every Canadian institution, and the understandable focus of Canadians on their own pocketbooks and circumstances, additional emergency response from Canada to every growing global need would be unwise. So goes the argument.

But it is in our interest to lead. I am suggesting in this report that a very different response is in fact required, and is in both Canada’s and the world’s interest. What cannot be in doubt is that we are now at a decision point. The pandemic is hitting the global economy hard and the response to it thus far, from the developed world, the United Nations (UN), the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank Group (WBG) and many other institutions, does not deal with the depths of the crisis.

Demonstrating the ability to promote collective and cooperative responses to crises such as the global pandemic is a moment to prove the value of multilateralism as a concept, and to prove the doubters wrong. At a time when many are claiming that the idea of a rules-based international order and collective action is a relic of history, demonstrating the ability of the international community to collaborate to resolve one of the greatest challenges of our time can serve to resuscitate the very notion of collective action over unilateralism.

International assistance until now

Coming out of World War II, Canada joined with the world in an effort to establish a new international architecture that included not only the UN, but a range of institutions whose purpose was to deal with the economic consequences of the War. The IMG, the WBG, regional/multilateral development banks (MDBs), the Marshall Plan and the growth of the European Common Market, the creation of ECOSOC, and then UNCTAD, the G-7 and then the G-20, the list goes on.

Lester Pearson, who played such a critical role in the formation of the UN itself, was asked by World Bank President Robert McNamara to chair a panel on why development was happening so slowly. His report, “Partners for Development”, was a clarion call for a shared commitment to a global prosperity that would be better shared and more sustainable. Mr. Pearson believed that the rich countries could be persuaded to do more on a multilateral basis, and to strengthen the post-war architecture that at that point had become frayed and was leaving a de-colonized world fragmented into the haves and have nots.

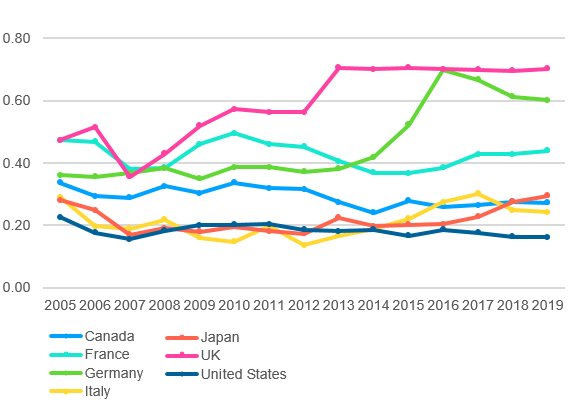

The Report called for wealthier countries to donate .7% of their Gross National Income (GNI) to Official Development Assistance, what is known as ODA.

Canada has never come close to that number, and if our rate this year looks slightly better than last year’s, it is only because the GNI number is stagnant, if not declining.

Official Development Assistance as % GNI

Text version

| Year | Canada | France | Germany | Italy | Japan | UK | United States |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 0.34 | 0.47 | 0.36 | 0.29 | 0.28 | 0.47 | 0.23 |

| 2006 | 0.29 | 0.47 | 0.36 | 0.20 | 0.25 | 0.51 | 0.18 |

| 2007 | 0.29 | 0.38 | 0.37 | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.36 | 0.16 |

| 2008 | 0.33 | 0.39 | 0.38 | 0.22 | 0.19 | 0.43 | 0.18 |

| 2009 | 0.30 | 0.46 | 0.35 | 0.16 | 0.18 | 0.52 | 0.20 |

| 2010 | 0.34 | 0.50 | 0.39 | 0.15 | 0.20 | 0.57 | 0.20 |

| 2011 | 0.32 | 0.46 | 0.39 | 0.20 | 0.18 | 0.56 | 0.20 |

| 2012 | 0.32 | 0.45 | 0.37 | 0.14 | 0.17 | 0.56 | 0.19 |

| 2013 | 0.27 | 0.41 | 0.38 | 0.17 | 0.22 | 0.70 | 0.18 |

| 2014 | 0.24 | 0.37 | 0.42 | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.70 | 0.19 |

| 2015 | 0.28 | 0.37 | 0.52 | 0.22 | 0.20 | 0.70 | 0.17 |

| 2016 | 0.26 | 0.38 | 0.70 | 0.27 | 0.20 | 0.70 | 0.19 |

| 2017 | 0.26 | 0.43 | 0.67 | 0.30 | 0.23 | 0.70 | 0.18 |

| 2018 | 0.28 | 0.43 | 0.61 | 0.25 | 0.28 | 0.70 | 0.16 |

| 2019 | 0.27 | 0.44 | 0.60 | 0.24 | 0.29 | 0.70 | 0.16 |

Despite this record, Canadians think of their country as generous, and deeply engaged on the international front. Canada is a member of both the G-7 and the G-20. We remain active on every continent, on the boards of a multitude of MDBs, and involved globally through both our humanitarian and development assistance. We are also actively engaged in multilateral organizations on migration and refugee issues. Canada has assumed a chair role for a multitude of fora, such as the Annual Tripartite Consultations on Resettlement, the Migration Five (M5), and has assumed a champion role for the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration.

Using any criterion - infant mortality, life expectancy, educational attainment, income, general well-being - prior to COVID-19 - the world was becoming a more prosperous place than it was in the 1960’s. Billions of people have been raised out of deep poverty. Countries that were profoundly underdeveloped in the 1960’s have achieved strong levels of growth and remarkable economic and social success.

However, in the past twenty years, the plight of the poorest and most vulnerable remains an international disgrace, despite the general improvement in economic circumstances. The financial crisis of 2008 was a body blow. Equally important, intractable conflicts in Afghanistan, Yemen, Iraq, Syria, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, South Sudan, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Burundi, northeast Nigeria, the countries of the Sahel, Cameroun, Venezuela, Central America, Myanmar, to name only some, have contributed dramatically to cycles of devastation and displacement.

The Impact of COVID-19

With the additional impact of COVID-19, which is at once a health crisis, an economic and social crisis, and a growing financial crisis, we are now seeing the reality of several countries facing famine, and many more face a plunge into deep poverty. A dramatic increase in conflict coupled with environmental degradation as the result of climate change - have now created a crisis affecting tens of millions, further exacerbating impacts on vulnerable populations. These numbers include refugees, particularly women and girls, including female-headed households, as well as internally displaced persons. These vulnerable people live in refugee camps, large urban settings, small towns, and in the countryside and are prone to facing marginalization due to their status, coupled with their intersecting identity factors including but not limited to, their gender and race. Malnourished and, in many cases, unable to work due to government restrictions, or working in informal jobs in risky and precarious conditions, they are now largely dependent on assistance in cash or food for survival.

UN agencies, including the World Food Program, UNICEF, UNHCR, OCHA, UNRWA, and the hundreds of organizations, both national and international that are responsible for dealing with this humanitarian crisis, have pointed out clearly in the last two months that the COVID-19 pandemic has made an intolerable and unmanageable situation even worse.

Haitian children washing their hands

Responding to these needs has been made more challenging by the restrictions faced by international actors, both UN agencies and international NGOs. They have faced limits on their movement and have had less access to the communities they are mandated to serve. Local partners and refugee-led organizations have mobilized to fill these critical gaps. They have demonstrated their ability to play a unique and essential role in collective action for refugees and the communities that host them, and need to be part of collective efforts to recover from the consequences of the pandemic.

At a time when solutions for those affected by humanitarian crises are so scarce, the closing of borders, limitations on travel, and curtailing of humanitarian activities have further eroded the trust between states that host the vast majority of the world’s refugees – who themselves face the enormous challenge of responding to the needs and priorities of their own citizens – and those countries that provide the majority of refugee funding, including Canada. Political dialogue and facilitation between these groups of countries, along with representatives from refugee communities, is needed now more than ever to develop responses and solutions that are not only gender-responsive, but also collaborative, cooperative and comprehensive.

While the immediate crisis will eventually pass, international financial institutions, like the WBG and IMF, also recognize that its aftermath requires a global strategy to respond to the plight of refugees and to rebuild for the long-term. In their June 2020 economic outlooks, both the IMF and the WBG reported a more negative impact on activity in the first half of 2020 than anticipated, projecting the recovery to be more gradual than previously forecast. The WBG has noted that the crisis highlights the need for urgent action to cushion the pandemic’s health and economic consequences, protect vulnerable populations, and set the stage for a lasting recovery. For developing countries, many of which face daunting vulnerabilities, it is critical to, not only strengthen public health systems but also implement reforms that will support strong, sustainable and inclusive growth.

This negative macro-economic picture is having a more dramatic impact on the developing world than anywhere else. It has drastically increased unemployment and the return of millions of workers to their home countries. Remittance flows have dropped off substantially, thus further lowering the standard of living of migrants’ families back home, and especially the families of female migrants, and also reducing the revenues of national governments. These countries are in no position to finance the kinds of support and liquidity mechanisms now common in the developed world.

As the gap between richer and poorer countries grows, this in turn creates the basis for more conflict, more difficulties and greater challenges.

Canadian COVID-19 Leadership: A new response from Canada

This raises the fundamental question for this year and going forward: should Canada’s financial support be limited to amounts budgeted well before the COVID-19 crisis, or should there be additional amounts? The answer is self-evident, and follows the logic of what every developed economy has done to respond to the domestic crises we have all been facing. We must do substantially more.

The steady march of COVID-19 virus across the world since January has been met by all governments, with varying degrees of success, with a commitment to saving lives by enforcing physical distancing, lockdown, and other public measures. As governments realized the dramatic impact this was having on economies, unprecedented measures were taken to support workers, families, and businesses affected. It is estimated that as much as $11 trillion has been spent by advanced economies, and more is coming. A fraction of this sum, $90 billion, could protect the world’s most vulnerable people from the effects of the current health crisis according to Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA).

The arguments in favour of this approach have not been couched in “generosity” or “charity”. Quite rightly, they have been justified as essential to national economies, and a reflection of lessons learned from the Great Depression, the war effort, and, more recently, the successful response to the financial crisis of 2008. The arguments for domestic recovery have been based on self-interest as well as solidarity.

Where the global effort has so far been lagging badly is the response to this very same crisis in the developing world. Thus far, the investments have nowhere near matched the need, and we are now at a genuine crisis point. What is required is the same logic that we have applied to our domestic issues be extended globally.

Both the health pandemic and the economic disaster are global in nature, and we shall only have a successful recovery if the pandemic ends and the world’s economy gets back on track. Neither can happen unless the developing world recovers. Canada’s recovery won ’t happen until there is a market for our products, and until we can be assured of a successful path to population health and global security. It is in our interest to do this, just as surely as it has been to extend support programs to Canadian citizens during the pandemic.

Just as Canadians’ health care more broadly has been impacted by the need to concentrate resources on the response to Covid-19, there are very serious health and social consequences for the developing countries beyond the pandemic itself. Food shortages are now growing to famine proportions, with people dying as a result. Sexual and gender-based violence is increasing exponentially as many women are in lockdown at home with their abusers. The inability financially and practically to sustain vaccination programs and other programs for a number of infectious diseases, particularly polio, measles, cholera, and malaria, alongside the interruption of other essential health services will mean a growth in deaths potentially worse than the direct impact of COVID-19.

And there is the equally critical question around the availability of a vaccine for COVID-19, when and if that much needed event happens. “Vaccine nationalism” is the next outbreak we shall have to deal with, because if it triumphs it will mean that billions will go without that critical protection and hence remain vulnerable to COVID-19. It will prolong the health and economic impact of the pandemic, as infections continue to increase and supply chains remain disrupted in low access areas. Without an effective global plan, resurgences around the world will mean that no one is truly safe. Prime Minister Trudeau’s outspoken commitment to equitable and affordable access for all and Canada’s interest in the development of the COVAX Facility and support to the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovation (CEPI) are important steps in the right direction.

Canada is also an early contributor to the COVAX Advanced Market Commitment (AMC). The COVAX AMC will use official development assistance funds to incentivize manufacturers through guarantees to ensure sufficient global capacity is in place before vaccines are licensed. It will then procure vaccines and assist in delivery in low income and lower middle-income countries. Combined, these countries account for nearly half of the world’s population.

Procuring enough vaccine to meet critical needs in low income and lower middle-income countries is only part of the equation however; delivering massive vaccination campaigns at community level will depend on local health care workers worldwide. We must facilitate their work and help their health systems to respond to COVID-19, while strengthening the global prevention and pandemic preparedness capacities that will enable the world to prevent, detect and respond more effectively to global health security threats in the future.

One further argument needs to be made. If we fail to act now, it is a certainty that a rapidly deteriorating condition facing a great many countries will become even worse, with catastrophic consequences in lives lost, hard-fought social progress deteriorating, and economies laid waste. At some point, the world will wake up to this, and then the costs of response will be even greater. This is not a guess or a prediction. It is a certainty.

This crisis requires a new response from Canada: building on what we have done so far, while recognizing that there is more to be done. It is partly about money and resources, but it is also about a clarity of vision and a willingness to put our shoulders to the wheel.

What is urgently required is more support for financial stability, more support for both development and humanitarian assistance, and a renewed commitment to face up to the crisis of forced displacement and refugees. Canada has also helped organize strong, rapid and coordinated action through the global architecture of the G20 and the IFIs to support the immediate financing needs of countries, including through debt service relief, in order to ensure that the global crisis does not exacerbate inequalities and reverse development gains for vulnerable countries. Canada should continue to play a leadership role in promoting the next phase of the global institutional responses so as to ensure the world recovers and takes the opportunity to build back better.

Canada has been working hard to add a critical third pillar to the agenda on development assistance, and that is the need for more innovative approaches to financial investment and assistance through direct equity investment, grants, and concessionary loans. This is even more urgent given the impact of COVID-19 and the growing need for recovery strategies that put the mitigation and adaptation demands of climate change.

Former UN Ambassador Blanchard was at the forefront of these efforts, and Canada has been co-chairing with Jamaica a major global effort to develop initiatives in the face of unprecedented challenges. Ministers of Finance will be meeting on Sept 8 to discuss options and Canada will need to ready to lead by example. The World Bank, the regional development banks and the IMF as well as the resources of the private sector will have to be mobilized if we are to make any progress on recovery and climate change

Forced displacement – the other crisis

There has been a crisis for the international refugee system long before COVID-19. While the COVID-19 outbreak prevented me from travelling to see the full impact of what is happening, I have been able to read and listen more. The evidence is tough to absorb, but we must be open to see and hear what is actually taking place. In considering my mandate and recognizing that there are many elements of humanitarian assistance, I will focus here on issues of forced displacement and what Canada can do in the face of this growing international crisis.

At the end of 2019, there were more forcibly displaced persons worldwide than at any time since the system was created at the end of World War Two – nearly 80 million by the count of the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR), including 26 million refugees and 45.7 internally displaced persons . For those who fled their own countries, the vast majority – 85% - did not go to Europe and North America, but sought asylum in states neighbouring their country of origin. Low- and middle-income countries facing their own development and economic challenges like Türkiye, Lebanon, Colombia, Pakistan and Uganda host the vast majority of the world’s refugees, not Canada.

Moreover, a system created to ensure protection for refugees and a way of resolving their plight is unable to do so on its own. The average duration of a refugee situation is now over 20 years. There are no apparent paths to security, dignity, and citizenship for refugees who cannot gain status in their host country and cannot safely return home. In 2019, only a tiny fraction of refugees (less than 0.5%) were able to be resettled to other countries like Canada, and resettlement needs keep growing while the number of resettlement spaces keeps falling. The result is growing frustration and impatience, from refugees and the states that host them.

The heart of the problem is political. What is urgently needed, especially in the context of COVID-19, is more sustained political leadership and dialogue that works to both address the underlying causes of humanitarian crises, while working to find lasting and rights-based solutions, with and for all refugees, migrants and internally displaced persons.

It took many years for the massive challenge of tragedy and displacement after 1945 to be resolved. The UN agencies created after that time focused on dealing with the enormous humanitarian task, and other discussions and negotiations were brought into play to address the underlying political issues. Humanitarian actors were not given the mandate nor the means to engage with political questions relating to refugees, nor to provide the robust investments in reconstruction needed to ensure durable peace. This is essentially the model that remains in place today, but without the sustained commitment to political dialogue and investing in reconstruction.

The UN agencies of UNHCR, UNRWA, and UNICEF have been joined by OCHA and IOM with a mission, to focus on addressing the needs and priorities of refugees, to co-ordinate key services, to assist in re-settlement where possible, and to negotiate with both donors and host countries on the myriad of issues that necessarily arise on a constant basis. They do this alongside thousands of NGOs, both national and international, local organizations and community-based responses by refugees themselves. However, they are not able to address the causes of displacement, and are thus not able, on their own, to find ways of resolving the issues that have led to these tragedies.

The use of the word “camp” itself is interesting, since it implies a place of dwelling that is both temporary and relatively small. Neither is true. Camps have become permanent living spaces, and the largest camp, in Cox’s Bazar in Bangladesh has a population of around a million people. In an earlier report for the government of Canada, “Tell Them We’re Human”, I documented my description of the Rohingya camp, and the conflicts that created it. Three years later we are no closer to a resolution of that conflict, and the humanitarian situation has been radically affected by COVID-19 and its impact.

View of Kutupalong refugee camp

The realities I described in that situation - the extent of the human trauma and devastation, the impact on women and girls, the lack of education, the lack of access to meaningful economic opportunities, the tensions between refugees and the host community, the security challenges, the intractability of the political conflict and the inability of the parties involved to be able to address these issues - have naturally affected my perspective on the refugee situation more broadly.

With COVID-19 facing communities around the world conditions are deteriorating rapidly, as international agencies have less access. At the same time, refugees are taking on the fight against their conditions, and have become the leaders on the ground. While OCHA recognizes that international actors are limited in their mobility and access to refugee communities due to the pandemic, refugees and refugee-led organizations, including those led by women, have responded with impressive innovation to fill critical gaps. They continue to demonstrate their ability to be front-line providers of social protection and assistance. This new reality will continue, and should lead to a greater respect for refugee voices and organizations, which in turn has implications for both funding and the need to include refugees in a meaningful way in discussions about how to resolve the crises at hand.

Canadian leadership in the refugee crisis

Why should Canada invest the time, resources and political capital to lead a global effort to respond to the challenge of displacement? Canada is currently a leader on the issue. Being the world leader in refugee resettlement for 2018 and 2019 in addition to our resettlement of Syrian refugees has increased our authority in the eyes of others. We have an ability to lead and broker the kinds of conversations between those countries that host the vast majority of the world’s refugees and those that provide the bulk of the funding for the international refugee system. And through our missions across the developing world, we have the tools, assets and expertise to make solutions for refugees a reality. We have done this before and we can do it again.

For decades, humanitarian assistance has been used as a substitute for addressing the political roots of the problem that forced refugees to flee and that prevents them from finding a place to call home and live safely. However, as the numbers of refugees and other forcibly displaced people hit record highs year after year, the levels of humanitarian funding internationally have plateaued. To help ensure that every humanitarian dollar spent by countries, including Canada, go as far as possible to meet these needs, the international community came together to create the Global Compact on Refugees (GCR) in 2018. The cornerstone of the Compact is an agreement that smarter, more strategic use of our international assistance is essential. This means ensuring that our humanitarian, development and peacebuilding efforts work in lockstep, each paving the way for and supporting the operations of the others. It means that new sources of funding – including from the IFIs, and the private sector – must be recruited to assist. Implementation of the Compact would also go some way to improve conditions for refugees and the communities that host them while they are in exile and to demonstrate greater responsibility sharing by third countries such as Canada.

Nonetheless, sustained political will is necessary to address the root causes of forced displacement internationally. Canada, with a strong record as an honest broker and bridge-builder internationally, can help.

Canada has been working across sectoral divides, uniting humanitarian, development and peacebuilding approaches in the Middle East to benefit refugees and the communities that generously host them. For instance, as part of our Middle East Strategy, Canada has improved access to quality education in Jordan by complementing our needs-based humanitarian assistance with longer-term development assistance to build resilient and quality education systems that benefit both Jordanian and refugee children. This is but one example of an approach to comprehensive responses, which the international community has endorsed in the GCR, and which Canada is well placed to expand on. We have done it in Jordan and we should be doing it in other refugee contexts.

Similarly, Canada is a strong voice for improved international cooperation in harnessing the benefits of migration. We firmly believe in the benefits of comprehensive, well-managed migration systems, and that the multilateral system and UN in particular can play a key role in a global approach to migration, which both protects the most vulnerable, and underscores migration as a driver for innovation, economic growth, social stability. Canada welcomed the 2018 adoption of the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration (GCM), which focuses on practical measures to protect and promote the human dignity of migrants and contribute to global prosperity. Canada has accepted the role of ‘champion’ for the Compact, which further enhances Canada’s profile as a global leader in migration, and strengthens our ability to support and influence international migration discussions, and GCM implementation in other countries.

The Government of Canada has made it clear that immigration will be integral to our COVID-19 economic recovery. Immigration will be a key economic driver, essential to our growth. Our ability to effectively and reliably manage and benefit from a large immigration program relies on a stable international system, well-funded and strong multilateral and international organizations, and the ability to manage migration effectively, including rights-based protection, gender-responsive approaches and solutions for refugees. Instability in one part of this system affects the system as a whole.

Canada has also led the way in refugee inclusion with policies, recommendations, and decision-making as well as in Canadian delegations to international conferences. Minister Mendicino has committed to working with other countries to ensure a similar approach. This in turn has clear implications for funding decisions for assistance delivery. Both NGOs and UN agencies need to show more support for localization and locally-based service providers. Canada should continue to press our UN and INGO partners on this issue and look for ways to deliver on our commitments to increased localization within our humanitarian and development assistance efforts.

Through its engagement on the GCR, Canada has committed to exploring complementary pathways that could supplement traditional resettlement, by addressing barriers that refugees face when accessing other immigration programs.

Learning centre in Kutupalong refugee camp

Canada has also committed to an increased focus on education among refugees. I saw first-hand in Cox’s Bazar the challenge facing the camps, and it took three years prior to COVID-19 outbreak to get some progress on the ground on this vital need for refugees inside and outside of camps. The pandemic has been a huge setback for education (as it has in every country in the world), and Canada needs to maintain a steady focus on this in the years ahead. According to UNESCO, school closures in response to the pandemic have affected over 90% of registered learners, interrupting their education, leaving them vulnerable to abuse and increasing food insecurity for the millions of children who rely on school meal programs. This includes millions of refugees who are in school, but who may already be vulnerable to significant barriers in accessing quality education. Moreover, over 3.7 million refugee children were out of school before the pandemic.

In this context, Ministries of Education around the world plan for the reopening of schools, when it is safe to do so, they must consider how to ensure that all previously enrolled children return to school, but also that those who were out of school – such as refugees – are also given access to quality education. The world’s most vulnerable and marginalized children and youth, including girls and adolescent girls, as well as refugees, will require additional support so that the devastating effects of the pandemic do not leave them further behind in accessing quality education.

Support to global education, including for the poorest and most vulnerable, is one of Canada’s top priorities. However, to ensure that no one is left-behind and that every child and youth benefits from inclusive, gender-sensitive quality education, targeted action needs to be directed at the most vulnerable. Canada has committed to ensure that all refugee and displaced children can get the education they need and deserve. I fully support this approach, but want to be clear that we also need to support international investment to provide hope for the refugee population around the world. At the same time, we need to support the ongoing effort to find rights-based, politically sensitive pathways to a resolution of underlying conflicts.

As important as education is, it alone is not enough. Education has to be part of a broader approach that includes opportunities to work, to find a pathway to personal security and dignity. Canada has made a point of seeking to eliminate child, early and forced marriage, a policy that is deeply rooted in our passion for human rights, gender equality, and the empowerment of women and girls. We know that gender inequality is a root cause of child, early and forced marriage. But we also need to understand the economic drivers that continue to make this a common practice, including in refugee camps. It is at least in part about families scrambling for economic security. We also quite understandably link strong education as a way of combatting radicalism and religious extremism. We need to appreciate, however, that unless education is linked to work, security, opportunity, and dignity, it will not alone be successful in the fight against extremism and criminal exploitation.

The regions closest to home are the also among the hardest hit – Latin America and the Caribbean is currently the global epicentre of the pandemic. This has resulted in a considerable deterioration of basic needs, exacerbating existing inequalities, while social and political issues, including violence against women, pervasive corruption, and organized crime, have persisted. Food security is quickly becoming among the top issues in the region due to interrupted global supply chains, loss of income, and climate change. The economies of our neighbours are buckling under the pressure of quarantine measures.

These compounding pressures are fueling the ongoing migration and displacement crises from Venezuela and within Central America as regional governments grapple with the impacts of the pandemic. Yet, these people have fewer and fewer options. Border closures have had an impact on thousands of migrants on the move, who find themselves stranded and unable to meet their basic needs.

Currently, the UNHCR estimates that there are more than 5.2 million Venezuelan refugees and migrants around the world, most in neighbouring countries. There are over 400,200 refugees and migrants from Central America worldwide, and over 318,000 internally displaced people in the Northern Triangle (El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras). People fleeing Central America take on enormous risks due to the high instances of violence, extortion, rape and sexual assault, murder, and disappearances along the irregular migration route. Despite border closures, deportations and forced returns from the United States and Mexico to the Northern Triangle have continued, including of COVID-positive individuals.

The pandemic is also having a significant impact on existing fragilities in Haiti, which continues to experience overlapping sociopolitical crises, high vulnerability to natural disasters, and rapidly deteriorating humanitarian and development indicators. People continue to leave Haiti in large numbers.

Since the pandemic started, Canada has been working to support partner countries in Latin America and the Caribbean to meet their longer-term development objectives, while also responding to the immediate needs of vulnerable populations affected by COVID-19, including refugees and migrants. More remains to be done to bridge the gap between the resources available and severity of the needs. The High Commissioner for Refugees has invited Canada to lead a group of countries to help do precisely this, supporting comprehensive and coordinated approaches in response to the displacement crisis in Central America. By accepting this opportunity, we can leverage our close ties with countries in the region to recover from the devastating effects of COVID-19 and achieve durable solutions for the hundreds of thousands of displaced persons who continue to struggle.

Solutions for refugees will not be found through any quick fixes. Special efforts to enhance refugees’ access to education, leverage economic opportunities for refugees, and address the incredible challenges faced by refugee women and girls are essential investments. Canada should continue to lead in these critical areas. But we also need to find political solutions to the issues that have given rise to the refugee crisis.

Canada should be a more ambitious champion of political dialogue with those who can unlock solutions, including states that host refugees, donor and resettlement countries and refugees themselves. Canada should encourage solutions by raising displacement issues in multilateral discussions that affect countries of origin and refugee-hosting states, including development, trade, finance and peacebuilding. Canada should also use its many tools to support the work of local partners and refugee-led organizations who are typically on the front-line of refugee responses and who will play a critical role in finding solutions.

The recommendations that follow should build upon what is rightly already a focus of Canada’s international assistance - continuing to prioritize the needs of the most vulnerable. Driven by a comprehensive approach to the political, development and humanitarian challenges that face the international community, Canada’s efforts will have the greatest impact. It is important to realize that leadership is not simply about having a vision, but about execution. In humanitarian and development assistance, we must do more, and better.

Recommendations

Securing Canada’s leadership during the COVID-19 crisis:

- The Government of Canada needs to allocate additional resources in support of the global COVID-19 response, as part of a broader effort by OECD economies to respond to the global financial, social, and economic crisis. More international assistance and humanitarian funding will be needed to support this response over the coming years. These funds should be additional to current commitments and estimated spending and support a balance of multilateral partners and local, national and international NGOs, all while continuing to prioritize the needs of women and girls and ensuring gender-responsiveness in their approaches. By targeting humanitarian needs, the health response and immediate socio-economic issues, Canada could significantly alleviate suffering and help build a bridge to recovery.

- As part of the development process, Canada must work to ensure global, universal, non-discriminatory approach to vaccine availability and distribution. This will require significant additional, ring-fenced funding to help procure and distribute doses internationally to the most vulnerable, complementing Canada’s vaccine diplomacy and domestic procurement.

- International Financial Institution (IFI) engagement will also be critical in the long term to support to respond to the financial impact of the crisis. Canada should work in cooperation with IFIs to facilitate their support. The leadership role that Canada is now playing in groundbreaking discussions between donor and host countries should continue, and be matched by our willingness to commit more funds.

Strengthening Canada’s leadership in humanitarian and refugee responses:

- At a global level, Canada should continue to lead in humanitarian discussions, while making solutions for those who are forcibly displaced a focus across our foreign policy, international assistance, and diplomatic action. This should involve strengthening our efforts to better integrate elements of humanitarian, development, peacebuilding to build comprehensive responses to forced displacement. We should promote solutions for refugees through our involvement in issue areas from development, peacebuilding, finance, trade and other aspects of the UN System. With every opportunity, Canada should be looking for ways that our convening power, history as a bridge-builder, and innovator in policy and practice can be brought to bear in resolving refugee situations.

- Canada should lead in finding the political solutions to the issues that have given rise to the refugee crisis. To do this, and given the non-political mandate of the international refugee system, Canada should create complementary mechanisms for dialogue between major refugee-hosting states, major donor and resettlement countries, and refugee leaders to support the political dialogue necessary to draft and realize solutions with and for refugees.

- Canada has a range of innovative diplomatic tools at its disposal, including international assistance, immigration and resettlement programs, trade agreements, support for refugee-led initiatives. These are resources that can be – and have been - used in national and regional contexts to unlock solutions for refugees. This is something Canada has done before. We can, and should, do it again. We can also use this engagement to promote successful Canadian initiatives such as private sponsorship of refugees, the inclusion of refugees on national delegations to conferences on refugee issues, and the consultation with refugee leaders of refugee related policies and issues like the newly created Refugee Advisory Network model in Canada supported by IRCC and GAC.

- In addition to enhanced and reliable funding for multilateral and international actors, Canada’s international assistance should include mechanisms, based at headquarters or in the field, to provide support for local partners, including national NGOs and refugee-led organizations with the capacity to manage funds and deliver services. As shown through the current crisis, local partners and refugee-led organizations add clear value to international responses and help fill critical gaps. They are also able to navigate local conditions and have deep connections with affected communities. They make invaluable contributions, and should be trusted partners in future responses.

- Notwithstanding the impact of COVID-19 on mobility around the world, Canadian leadership on resettlement remains important. We have learned from history the injustices that are compounded by shutting the door to those seeking safety and opportunity. This lesson should guide public policy as the risks of pandemic are better controlled. Our leadership on resettlement should continue, knowing that our example will have an important effect on the behaviour of others. This includes continued leadership in sharing Canada’s model of community sponsorship with other countries.

- While every part of the world is affected by COVID-19 and its broader implications, the impact of the crisis in the Americas is expected to result in a considerable deterioration of basic needs and inequalities with the increases being amongst the highest globally. UNHCR has proposed that Canada chair the regional support platform for displaced persons in Central America. We should accept that challenge. Nearby, Haiti continues to be a greatly fragile country, especially in this time of crisis. Canada cannot give up on Haiti and should continue to support and demonstrate leadership, including as chair of the ECOSOC Ad Hoc Advisory Group on Haiti at the UN. Canada should also continue its leadership on supporting Venezuelan migrants and refugees, facilitating efforts to bring about a political solution for a peaceful restoration of democracy, and increasing its international assistance inside Venezuela to respond to urgent needs and prepare for future recovery.

- Date modified: