Indigenous health and well being: Youth lead call for change

Women Indigenous dancers perform at the opening ceremony of the World Indigenous Suicide Prevention Conference.

“If you take away the accents, Indigenous youth in Canada and Australia are experiencing the same thing.”

Short life expectancy. Infant mortality. Malnutrition. Tuberculosis. Suicide.

These are just some of the harsh realities faced by Indigenous communities.

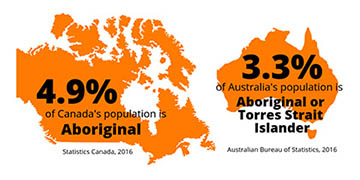

And sadly, Indigenous peoples around the world face these health challenges at alarmingly higher rates than non-Indigenous people.

But there is hope. Indigenous youth and leaders around the world are working together, calling for action and making positive change. The High Commission of Canada in Australia is proud to support them.

Shared past, shared challenges

Indigenous peoples in Canada and Australia both experienced a similar pattern of British colonization, including discriminatory policies and the systematic removal of Indigenous children from their families. In Canada, children were taken from their families through the Residential School system and forced into adoption or foster care. In Australia, the children who were separated from their families are called the “Stolen Generation.”

Because of this, Indigenous peoples in both countries share many commonalities.

This includes overrepresentation in the criminal justice system, higher rates of poverty, and record numbers of children in the child welfare system.

It also includes significant challenges to health and well-being.

Health is determined not only by physical factors, but also social, economic, cultural and political disparities, called the social determinants of health. This means that discrimination, marginalization and poverty directly affect health.

As Indigenous peoples continue to face social, economic, cultural and political discrimination, their health continues to suffer.

From Canada to Australia: Making connections

Indigenous communities in Canada and Australia are working together to share knowledge and find solutions.

The High Commission of Canada in Australia was proud to invite Dr. Nadine Caron to deliver the keynote speech at the National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organization Conference in Brisbane.

Dr. Caron has first-hand knowledge of the health crises facing Indigenous Canadians as Canada’s first general surgeon of First Nations descent and co-director of the Centre of Excellence for Indigenous Health at the University of British Columbia.

She explained the disparities in physical and social well-being between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples in British Columbia, which includes higher incidences of disease, higher suicide rates and lower life expectancies.

Dr. Caron emphasized the negative effect that colonization, residential schools and assimilation policies have had on health and well-being.

But there is also a corresponding positive effect of culture, ceremony, language, connection to land and self-determination on Indigenous health.

Dr. Caron says these social changes should be a key part of improving Indigenous health.

“It is not enough to simply try to close the gap. Indigenous peoples should strive to do better than the norm.”

Addressing the suicide crisis

Suicide is one of the darkest and saddest crises facing Indigenous peoples around the world today.

In both Canada and Australia, Aboriginal peoples commit suicide 2 to 3 times more often than non-Aboriginals. In Australia, that means over 25 per 100,000 Indigenous people committed suicide. In Canada, suicide and self-inflicted injuries are the leading causes of death for First Nations youth and adults up to 44 years old.

At the Second World Indigenous Suicide Prevention Conference (WISPC), the Whadjuk People of Noongar Nation near Perth, Australia, welcomed over 500 Indigenous peoples from around the globe to connect and find solutions to prevent Indigenous suicide.

Traditional song, dance and ceremony from nations around the world created an environment of peace and mutual respect for all cultures before addressing such a profound issue.

Twenty-six Indigenous Canadians, including 16 youth, travelled to the conference with the support of the Canadian High Commission to Australia.

Canadian youth lead call for change

Sixteen young leaders from the Nishnawabi Aski Nation (NAN) and Cree Nation travelled from Canada to the west coast of Australia to raise awareness of the alarming rates of Indigenous youth suicide.

Indigenous youth in Canada face even higher rates of suicide than Indigenous adults and Inuit youth have one of the highest rates in the world.

Unfortunately, the statistics are very similar for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders in Australia.

“We want our children to feel love, want to live and to choose life.”

Metis youth film director Madelyn Pilon presented her documentary, Feathers Falling, at the Conference. The film reveals the real lives behind the statistics and questions why these tragedies continue to happen.

NAN youth leader Samuel Kloestra spoke about the impact of poor educational facilities. 47% of First Nations communities in Canada need new schools and only 22% of First Nations have access to early childhood education.

Quality education can be a path out of poverty and contribute to positive health and well-being, while inadequate education contributes to negative social, economic and health outcomes in the future.

These inspiring Canadian Indigenous youth are fighting to ensure the unacceptably high rates of youth suicide are addressed and that no more lives are lost.

The work continues: Looking ahead to 2020

Community-driven approaches, like those discussed at these conferences, have proven effective in improving Indigenous health. But there is much more work to be done.

The collaboration will continue in 2020 when the 3rd World Indigenous Suicide Prevention Conference will be hosted on Treaty 1 territory in Manitoba, Canada.

The healing Mauri stone was presented to Ms. Leona Starr and Ms. Carla Cochran of the First Nations Health and Social Secretariat of Manitoba for safe keeping until then.

The High Commission of Canada in Australia was proud to support these conferences and remains dedicated to partnering and advocating for Indigenous health and well-being.

Canada is committed to improving Indigenous health and well-being in both Canada and around the world as part of reconciliation and a renewed, nation-to-nation relationship with Indigenous peoples.

If you're experiencing emotional distress and want to talk, call the First Nations and Inuit Hope for Wellness Help Line at 1-855-242-3310. It's toll-free and open 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

If you or someone you know is in immediate danger, call 911 or the number for emergency services in your community.

Related Links

External links

- Date modified: