A career helping to chart Canada’s global path

Isabelle Bérard looks back on her career in international development punctuated by major events, including the 2010 earthquake in Haiti.

When she was asked to write about her career in international cooperation for a senior executive leadership program a few years ago, Isabelle Bérard called it a hike.

“I like endurance, not sprinting; the things that happen when you put in the effort and set a goal,” she explained, detailing stages of her position that involved deep exploration, demanding tasks and new horizons.

Having recently retired as assistant deputy minister for sub-Saharan Africa at Global Affairs Canada (GAC), Bérard, 55, reflects on the milestones of her journey, as well as the role she played in helping to chart Canada’s global path over the last 33 years.

Her early career goal had been not to venture far beyond her home of Montréal. Indeed, Bérard felt so attached to the city that she studied urban planning at the University of Quebec in Montréal, in the hope of working for the municipality or an architecture firm.

But then her route changed dramatically.

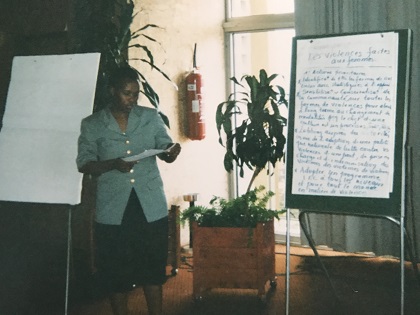

Isabelle Bérard, in the Democratic Republic of Congo, formerly the Republic of Zaire, in 1989.

“When I was doing my studies, all of a sudden I realized that there was a world out there,” she recalls. The next step was a 1-year graduate degree at the University of Ottawa in international cooperation. “It was just starting, this concept of allowing students to get more familiar with what’s going on in terms of cooperation elsewhere,” says Bérard, who found “lots of intersection” between the program and urban planning. “It was dealing with the same issues: communities, environment, how societies evolve, how you make sure people get sustainable livelihoods.”

Being in Ottawa deepened the experience. “It opened my eyes to a number of other things happening on the international front, not only cooperation but international relations and, of course, politics.” Through her studies, Bérard also got a “much better sense of inequalities around the world,” she says. “I knew that there were inequalities in Montréal. And I kind of figured that there were some elsewhere. But it was an eye-opener from that perspective.”

The realization that “there are people who are trying to work globally to address big, big issues” made her turn away from purely domestic matters completely. “I suddenly felt I could somehow be part of the solution.”

Now to get a job. Bérard had learned the importance of financial autonomy from her mother, who as 1 of 16 children had left after primary school to help at home and was frustrated that she couldn’t pursue a career and be financially independent.

When Bérard graduated in 1988, a natural place to look for employment was the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA). While there was a public-service hiring freeze, she brought an important skill to a summer internship there. She’d used computers as a student, and while “I’ve never been a geek…I had a bit of an edge on the technological front.”

At CIDA, “they still had typing pools,” but computers were being installed. “So that’s how I started, as a techie,” she says, helping staff get acquainted with the technology. “I would go from one officer to the next, explaining how a computer works, how to save your work…The idea of having different versions of a document was so remote. It took hours for people to understand the concept.”

Deep exploration

Isabelle Bérard on a business trip to Mozambique in 2020.

Each lesson presented an opportunity to promote her other abilities. “I would say, ‘You know, I haven’t studied IT; I’m not a computer specialist. I’ve studied urban planning and did my graduate degree in international cooperation.’” Bérard’s story piqued the interest of Raymond Drouin, a senior program officer in the Partnership Branch, who wanted to speak further “once the computer was set up,” she allows. He was interested in using computers to apply lessons learned in a series of projects being set up to provide financial assistance to women starting small businesses in 5 African countries. Bérard was brought in to help establish a system using Excel spreadsheets to gather, monitor and compare the project data.

She remained as a consultant at CIDA for 5 years before being hired and moving through a series of development officer positions. She preferred working at the country and community levels on issues such as health, education, environment, economic growth and governance, “which are very similar to what you’re doing when you’re an urban planner.” This brought her to more senior positions in the Africa Branch from 2000 to 2008. It was a formidable period, given Canada’s support for the African Action Plan at the 2002 G7 Summit in Kananaskis and the country’s commitment to double aid to Africa.

At the same time, the “international community was coalescing” around the Millennium Development Goals, “and we had come up with a road map to work better together” through the 2005 Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness, Bérard says. “There were lots of things happening and it was very, very exciting.”

Photo taken by Isabelle Bérard in Rwanda in 1998 as the country was recovering from the 1994 genocide.

One of her favourite parts of the job was being “on the ground and meeting mostly with African women.” For example, back in 1997 working in the Rwanda program right after the genocide in the country, “a number of things had to happen so women could actually have access to a bank account, own a house, be able to function,” Bérard recalls. “There were fewer men left, so all the laws had to be adjusted so women could survive. That was fascinating to look at women, be they Tutsi or Hutu, and what they could do together to get themselves out of poverty.”

While she travelled a good deal, visiting some 70 countries throughout her career, Bérard was never posted overseas, despite warnings that this would stop her from moving up through the ranks. She’d started a family in between positions as a consultant, she explains, and her husband Bruno Cadieux could not work remotely. “He was the backbone of our organization from a financial perspective.”

Bérard was also cautioned that she had too much fun on the job. “I like having a good laugh…I was very often told during my career, ‘Stop, you don’t look serious. Making jokes, that’s not good. You won’t go anywhere.’” There were elaborate costumes at Halloween, appearances in silly videos, and “even in very serious meetings, I would always make sure that either at the beginning or the end we’d find a way to make things a little bit lighter.”

Demanding tasks

Bérard organized parties after work every other Friday, even at the most challenging times, such as when she worked as director general of Haiti and the Dominican Republic. She recalls a colleague coming in with the news that a massive earthquake had struck just outside of Haiti’s capital of Port-au-Prince at 4:53 pm on January 12, 2010.

“Within minutes, we knew that something really bad had happened,” she says. “We were facing a huge catastrophe.” Bérard led a team of staff at headquarters and in the field through 3 years of intense work. “The first couple of days and months were really brutal on me, on the team, on Haitians. From a leadership perspective, it was certainly the most difficult experience I’ve gone through.”

Isabelle Bérard visits Haiti as director general of Haiti and the Dominican Republic.

There were stand-up meetings twice a day, part of a highly effective government crisis-management system. “When you want to be proud of being a public servant, you just have to observe what’s going on in the crisis cell that’s set up when there is a crisis to deal with,” she says.

Staff were not authorized to use Facebook at the time, but an exception was made so they could scour it “to figure out who was still alive and who wasn’t.” A major preoccupation for CIDA was its partners in some 80 projects on the ground, who had been killed or lost spouses and children, she says. “Every day was bringing a new twist to the entire story.” Bérard, who prides herself on being consultative before rapidly deciding on a course of action, “had to take decisions every 10 minutes. I didn’t have the luxury of mulling over whether I should do something or not.”

When she visited Haiti in early March of 2010, “everything was destroyed; it was apocalyptic,” she remembers. “Yet just having the opportunity to see those who had managed the crisis standing on their feet…it was very, very reassuring.” The Canadian recovery assistance, ably led by Gilles Rivard, Canada’s Ambassador to Haiti, included setting up huge bunkers to allow the country’s government to operate and helping clear tens of thousands of people from a sprawling camp on the Champ du Mars plaza, across from the destroyed presidential palace. “In the end, we helped each and every one in the camp to relocate, find work, et cetera,” Bérard says.

A decade later, she’s pleased with the job her team did, but is realistic about the hurdles the country faces. “The needs are so great in Haiti. It was a challenge before, it was a challenge then and clearly it remains a challenge. But we definitely made a difference.”

New horizons

There were many other turning points for Bérard and CIDA, such as the creation of GAC, which amalgamated foreign affairs, trade and development. From 2017 to 2019, she took a position at Environment and Climate Change Canada as assistant deputy minister for international affairs. It was an intensive time, given Canada’s activist environmental stance at the United Nations Conference of the Parties, as well as in the G20 and G7. There were negotiations on the environment chapter of the Canada-United States-Mexico Agreement and the country’s leadership position on the “plastic agenda”. She was valued for her familiarity with GAC and with the management of the international assistance envelope as the government implemented its $2.65-billion, 5-year commitment to climate change.

She returned to GAC in 2019 and her career came full circle as assistant deputy minister for sub-Saharan Africa, this time overseeing the political and trade as well as development aspects of the relationship. She helped organize the travel to Africa of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and 4 ministers, who visited 11 countries over 10 weeks. She also assisted with Canada’s campaign for a seat on the UN Security Council, which coincided with the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic and the massive effort to repatriate Canadians scattered through 48 countries of sub-Saharan Africa. “It was a crazy, crazy period. We were working night and day.”

As well as organizing the evacuations, staff looked through each project in the annual programming budget of $700 million for ways to help address COVID-19 issues there, she says. “We turned every rock and readjusted the portfolio.” After the pandemic, she sees “significant opportunities ahead” between Africa and Canada, extending beyond development to trade, for example in sectors like clean technology. “We need to seize that moment.”

Much has changed about the job throughout her career, no more so than with the progression of technology. “When I started, I was helping out with computers. Then fax arrived, which was a revolution,” she says. “And here we are today using Microsoft Teams and other platforms to meet virtually. It’s unbelievable.”

Looking back, Bérard is grateful that from her early days she had the opportunity to observe great leaders, and aspired to be one herself. “I knew I had some capacity to bring people together to achieve something,” she says. “Public service is a great place to be when you have the stamina to do this.”

Does she feel she’s made a difference? “In the big scheme of things, it’s the combination of everybody’s efforts that makes a difference,” Bérard says. “But I’ve certainly tried my best to contribute to finding solutions…I’ve observed projects where we’ve made a huge, huge change, and a sustainable one, in the lives of kids, the lives of women and the lives of communities.”

Bérard’s future plans include possibly getting involved in business or politics. For now, she enjoys long walks in the countryside around her home outside of Wakefield, Quebec. And she looks forward to hiking in countries farther afield once travel is possible.

- Date modified: