Building Back, Giving Back: Refugees Model Compassion

Building resiliency out of adversity has become a common theme of the pandemic, as Canadians overcome new stresses and untold hardships brought by the COVID-19 crisis. For the refugees among us, resilience is an everyday fact of life, requiring strength, determination and even ingenuity.

The stories of two refugees show how these qualities are helping them to succeed – and help others.

Returning the embrace

After arriving in Nova Scotia as a refugee, Tareq Hadhad was asked by a man why he was taking jobs away from Canadians. His response was simple.

“It was an emotional moment,” Hadhad recalls. “I told him, ‘We did not come to Canada to take jobs, we came here to create them.’”

Hadhad and his family of confectioners are perhaps the best known among the wave of Syrian refugees who arrived in Canada beginning in late 2015. They had lost their Damascus home and business – a chocolate factory with 500 employees and sales around the Middle East – to the war in Syria. Hadhad, 28, credits the success the family has had since arriving in Canada with a suggestion from an immigration counsellor as they waited in Lebanon that it would be better for their integration not to relocate to a large city.

“A small town would give us more attention, more care,” he explains. “There would be more people around us, there would be a really amazing sense of community and support for our family in the first few years of our lives here.”

The Hadhads were sponsored by a group in Antigonish, Nova Scotia, called Syria-Antigonish Families Embrace, or SAFE. And they quickly began returning the embrace. “Giving back to Canada was the bare minimum that we could do,” he comments. They started making chocolate and donated profits from early sales to relief efforts for the 2016 Fort McMurray wildfires.

“We also asked other newcomers in the country to help us, and they did,” Hadhad says. “We all knew what it means to lose your home in a blink of an eye.”

The campaign inspired their company name, Peace by Chocolate, and in 2018 the family started the Peace on Earth Society, which donates a percentage of revenues to peace-building projects around the world. It supports partnerships with local groups like the Paqtnkek Mi'kmaw Nation, an Indigenous community near Antigonish, and national organizations such as the Canadian Mental Health Association, Refugee Hub, which helps new refugees to resettle.

Tareq Hadhad wears a T-shirt displaying a peace sign that symbolizes his family’s Peace by Chocolate business and their giving back campaign. Photo: Applehead Studio

“The kindness in Canada is a circle,” Hadhad says. “You give and you get, you give and you get. It’s the law of reciprocity.”

The COVID-19 pandemic was difficult for the business, which shut down and laid off its entire staff for several months starting in March 2020. It began rebuilding last August, reopening the factory and adding new products.

Peace by Chocolate today has 55 employees, between full-time, part-time and seasonal staff. It has a shop in Antigonish, a new flagship store in Halifax, a growing wholesale business and export sales. Hadhad hopes it will completely recover from the impact of the pandemic by the end of this year. It has committed by 2022 to hire 50 refugees and support 10 businesses started by refugees, through marketing and other initiatives.

Nine members of Hadhad’s family and many other Syrian refugees now call Antigonish home.

“The last family came a few months ago, and to welcome them during their quarantine we did a car parade around their house, to let them know that we are with them,” he says. “The idea was to make sure that whoever's arriving during the pandemic is feeling the same sense of welcome that our family felt.”

Lessons of resilience

Relocating to Canada presents many challenges for refugees, from overcoming past uncertainties to the difficulties of starting a new life here. For Monyror Bior, it has also come with lessons, eye-opening experiences and an opportunity to help others.

Bior, 27, grew up in South Sudan. He fled the conflict there with his family in 2014 to live in a refugee camp in Uganda, where he became a teacher. He arrived in Canada in September 2019 as part of the Student Refugee Program run by World University Service of Canada (WUSC). The initiative launched in 1978 combines resettlement with opportunities for higher education. A cohort of 130 to 150 refugees from six countries of asylum in Africa and the Middle East come to study each year in Canada as permanent residents, sponsored by groups on campus for their first year of classes.

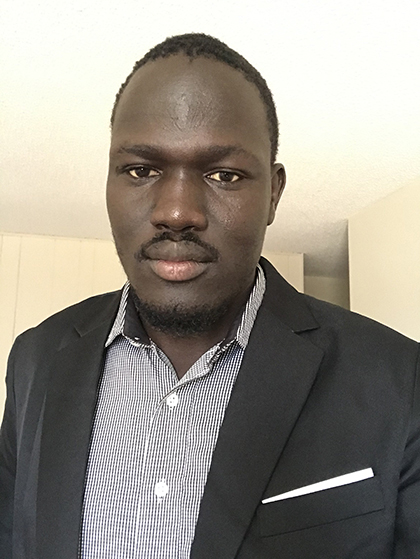

Monyror Bior fled the conflict in South Sudan in 2014 and arrived in Canada in 2019.

Bior, who is studying social work at the University of Regina, says that when the COVID-19 pandemic halted in-person classes in March 2020 and classes went online, “for me it was a setback.” He wasn’t used to working and especially doing exams on the computer. “I passed, but they were not my expected results,” allows Bior, who found the online classes in his second year somewhat better.

He’s now become a volunteer student leader in the WUSC network and co-chair of the local committee overseeing this year’s cohort of refugee students at the University of Regina. Because of the COVID-19 crisis, instead of arriving last autumn they landed the week before Christmas. Bior provides assistance to the 6 newcomers, from helping them apply for health cards and activate their bus passes to searching out favourite foods in local shops.

Bior has also volunteered in the after-school homework-help club of the Regina Open Door Society, a non-profit organization that provides settlement and integration services to refugees and immigrants. He feels that such students can excel, despite their many stresses. “There is no other option other than to adapt.”

Monyror Bior is spending this summer planting trees in remote British Columbia.

Last summer he worked as a grocery store cashier in the small aboriginal settlement of Île-à-la-Crosse in Northwestern Saskatchewan. He’s now spending four months planting trees in remote British Columbia. The work is taxing, sleeping in tents and sampling unfamiliar foods like preserved sandwich meats. “I end up eating only the bread,” he admits.

The jobs help him pay for his education and living costs, which became his responsibility after the 1-year WUSC sponsorship ended. He also wires money to Uganda to support his two stepmothers living in refugee camps there, one of whom has 5 children and the other with 6 children.

Canadians in remote parts of the country that Bior has visited are curious about his background. “I just tell them I'm from Africa, because sometimes I don't like using the word ‘refugee,’” he says. “There’s an assumption that somebody is supporting you. But many refugees are responsible for themselves.”

Bior hopes his third year of university this autumn will bring a return to the classroom. He would ultimately like to become a social worker or lawyer and help people in Canada who are living in vulnerable situations.

- Date modified: