From child soldier to activist

Kidnapped by a gang of militia from the playground of his school in the Democratic Republic of Congo as a child, Michel Chikwanine was forced to do things unthinkable for a 5-year-old. He was recruited to become a child soldier through a process of intimidation and indoctrination in which he was drugged, blindfolded and made to shoot and kill his best friend.

While Chikwanine managed to escape from the rebels after a few weeks, the fear and anxiety he’d felt under their control remained. In the classroom of an Ottawa high school in 2004, those feelings rose to the surface and made his childhood experiences into a lesson for others.

As a newcomer to Canada, he was bullied for his accent and “looking a bit different,”

turning the 16-year-old “from being this happy new kid in school to being very quiet.”

The taunts came in particular from a girl who sat at the back of the class. He remembers she was using an assignment in which the students were asked to write an essay about an impactful moment in their lives to complain about the colour of the cellphone her parents had bought her.

For the same assignment, Chikwanine wrote about how “conflict minerals”

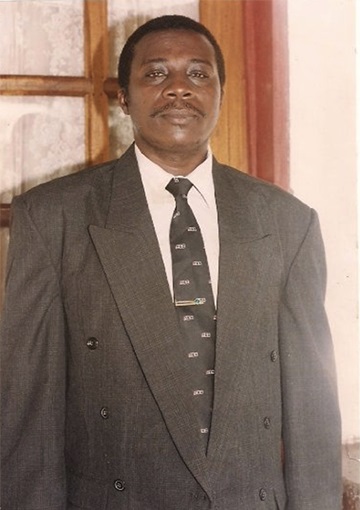

used in such everyday electronics fuel wars and human rights abuses in countries like the Democratic Republic of Congo. This resulted in the recruitment of child soldiers and the targeting of activists, such as his parents, he wrote. His family had been forced to flee the country after Chikwanine’s father had been abducted and released and his mother and 2 older sisters were raped before his eyes.

When he was asked by his teacher to read his essay aloud to his fellow students, Chikwanine remembers that he “gained back power and some normalcy in my life in high school, from being bullied.”

Today, he continues to share his experiences through his work as a motivational speaker and as co-author of a graphic novel called Child Soldier: When Boys and Girls Are Used in War. The book, published by Kids Can Press as part of its CitizenKid series, for readers aged 10 to 14, recounts Chikwanine’s harrowing capture and its devastating lifelong impact.

“This really was a psychological war and wound that still I have not recovered from fully,”

says Chikwanine, now 34 and living in Toronto. “It’s an awful thing to go through. The scars themselves last a lifetime.”

As the world marks the International Day against the Use of Child Soldiers, known as Red Hand Day, Chikwanine supports Canada’s efforts to draw attention to the problem and to help children affected by it. This includes promoting the Vancouver Principles on Peacekeeping and the Prevention of the Recruitment and Use of Child Soldiers.

“Taking a leadership role on this topic is so important for Canada,”

he says.

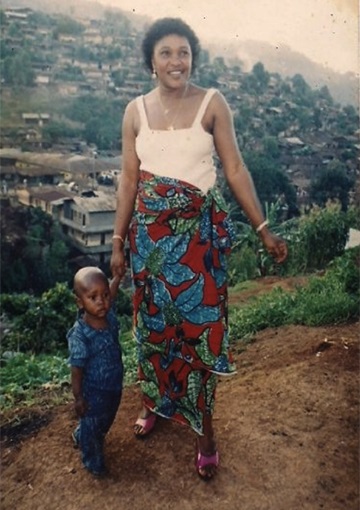

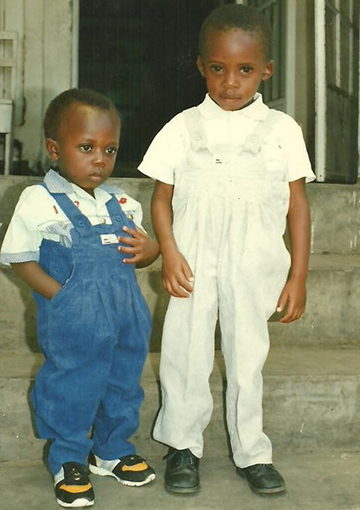

Chikwanine was born in the town of Beni, in the Democratic Republic of Congo’s eastern Rwenzori Mountains, near the border with Uganda. Until his abduction in 1994, his early life was untouched by violence. “The only time I had ever seen a gun was during movies, when I watched Rambo with Sylvester Stallone, or when we’d make AK-47s out of banana trees,”

he recalls.

As the country moved toward civil war, the region found itself “on the periphery of conflict,”

with rebel groups hiding in its dense jungles. His father Ramazani Chikwanine, a human-rights activist, and his mother Chibalonza Enungu Byamungu, an entrepreneur who helped women start businesses, were attacked and the family’s belongings were burned. In 1998, they all fled to Uganda, where his father was assassinated.

Canada has provided a welcome refuge to Chikwanine, his mother, 2 of his sisters and their children. According to Chikwanine, the country “has shaped me into the person that I am today… I might have been born in Congo, but I grew up in Canada.”

His new home has influenced “the way I have come to see the world. I love it here. I love every group, every friend that I’ve made, every opportunity that I’ve had.”

After high school, he spent several years travelling around North America as a public speaker and facilitator, which led to the publication of Child Soldier in 2015. Chikwanine is grateful to know how telling his story affects young people. For example, after he addressed an inner-city school in New York City, he was approached by a student whose brother had been killed by a gang and was planning to take revenge. “I was talking a lot about forgiveness, and how I forgive the people that killed my dad. It had such a huge impact on him,”

he remembers.

In 2018, Chikwanine graduated from the University of Toronto with a bachelor’s degree in African studies and minors in economics and international relations. He went on to a fellowship with the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights in Geneva, as part of the International Decade for People of African Descent. He has had positions in organizations such as the Dallaire Institute for Children, Peace and Security and he would like to have a job involving young people and refugees.

His work has included helping to develop training programs for peacekeepers who encounter child soldiers on the battlefield. Chikwanine is pleased that Canada is at the forefront of the issue of child soldiers, calling the Vancouver Principles “the right step.”

He’s frustrated that people focus on the problem only “where the cameras are.”

He feels it’s critical to deal with its root causes, including poverty and the glut of weapons around the world.

Chikwanine has returned to the Democratic Republic of Congo just once, and only to the capital of Kinshasa. “I still have not made it to the east of Congo, just out of fear, honestly,”

he says. The trip he took last summer was to marry his wife Jovany, whom he met through an aunt in the country. The couple is going through the process of applying for Jovany to immigrate to Canada, and they will welcome a son in March.

- Date modified: