Refugee brings passion and poetry to the Rohingya cause

Arriving in Canada as a Rohingya refugee at the age of 19, Yasmin Ullah was determined to better her life through higher education. Her family had fled from persecution in northern Rakhine State in Myanmar when she was 3 years old. She then lived in neighbouring Thailand before settling in Surrey, British Columbia, with her father and brother in 2011.

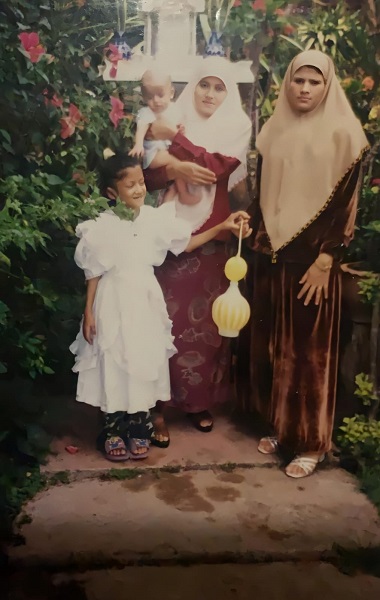

Yasmin Ullah (left) lived in Thailand after her family fled from persecution in Myanmar when she was 3 years old. In this 1998 photo she is pictured with her mother holding her infant brother, as well as her aunt.

Courtesy of Yasmin Ullah

Ullah entered university 2 years later with a goal to work in the medical field. But having grown up speaking Rohingya and Thai, she found that she lacked the skills to think critically in English. Struggling in her classes, she quit school and got a job as a receptionist and chair-side assistant in a dental office.

The gap in her studies not only helped Ullah get over her “language hurdles,” she recalls, “it really helped me to look deeper into myself to see what I really wanted to do in the future.” This became clearer in the summer of 2017, when hundreds of thousands of Rohingya were forced to flee mass atrocities in a military crackdown in Myanmar. Ullah turned to speaking out about the humanitarian crisis and promoting an online crowdfunding site that distributed donations to people devastated by the attacks.

Yasmin Ullah is a student, poet and social-justice activist.

Courtesy of Yasmin Ullah

Returning to the classroom the following year, Ullah changed the focus of her undergraduate degree to political science and sociology. Those were disciplines she felt would “push me forward in my path” of a career in the field of human rights. “They also helped me to better understand the state of the world and how I could help.”

Today Ullah, 30, calls herself a social-justice activist. She’s 1 of about 1,000 Rohingya refugees now living in Canada, according to the Rohingya Association of Canada. The group works to raise awareness about the plight of the Rohingya in Myanmar and those displaced in refugee camps beyond its borders.

As a consultant and advocate, Ullah speaks passionately about the 2017 attacks against the Rohingya, which Canada recognized as constituting genocide through a motion in the House of Commons in September 2018. She spreads the word about the difficulties faced by the Rohingya at conferences and shares her story with the media.

Yasmin Ullah spreads the word about the difficulties faced by the Rohingya at conferences and shares her story with the media.

Courtesy of Yasmin Ullah

She helped create a learning tool called Us vs. Them for the Montreal Holocaust Museum, to be used by teachers to help students learn about the origins of the genocide. Ullah was also an adviser to an exhibit held at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights in Winnipeg called Time to Act: Rohingya Voices. It profiled her story in an article about Rohingya women calling for justice.

She is past president of the Rohingya Human Rights Network, a non-profit group of Rohingya activists across Canada. And she’s on the steering committee of a project called Bridges MM, a “safe space” being created for young Myanmar activists and leaders to exchange views on humanitarian issues.

Yasmin Ullah says that if Canada can work with its allies to ensure safety, protection and sustainable solutions for the Rohingya, it "would be life-changing for people like myself who are still stuck in the camps or in Myanmar.”

UNICEF Bangladesh/2019/Modola

“We also invite experts in different fields of human rights to share their insights and wisdom on the current struggles and how best to deal with them,” explains Ullah, who feels it’s important to find solutions to ethnic oppression in Myanmar from within. “Connecting on a personal level helps us get closer to that goal.”

Ullah is also a poet, having found solace in poetry from a young age. “It got me inspired to try to express what it’s like to be a Rohingya, what it’s like to go through the journey of this whirlwind of separation and violence, and how we make art out of it,” she explains. She declares she’s “very much an amateur, but I feel that through poetry, I can definitely say more with fewer words.” Two of her works were published in I Am a Rohingya: Poetry from the Camps and Beyond, a 2019 anthology of poetry. She’s also authored an illustrated children’s book that will come out in the summer. Titled Hafsa and the Magical Ring, it explores the topic of displaced people turning organic materials into useful objects.

Ullah will soon finish her degree and hopes to go on to graduate studies, with a goal to become an international human rights lawyer and eventually a professor. She got her Canadian citizenship in 2016 and is thankful that her family “finally found a home” here. She’s also grateful for what this country has done for the Rohingya people, while she hopes it can do more.

“Canada is well positioned and well respected by the international community. What we say matters, and what the Canadian government offers as a solution or as guidance or as advice has a lot of weight,” she says. “Working with our allies to ensure safety, protection and sustainable solutions inside the camps and in Myanmar would be life-changing for people like myself who are still stuck in the camps or in Myanmar.”

Yasmin Ullah stands in front of the International Court of Justice in The Hague in early 2020.

Courtesy of EFE News

She feels the people of Canada can appreciate the difficulties of the Rohingya, the world’s largest stateless population. That’s because their story is one of struggle, “which everybody can relate to,” Ullah comments.

“I hope Canadians can see that the Rohingya people are not very different from Canadians, or anybody on this earth, really,” she says, adding that their ordeals to date should be seen as proof of their strength rather than their victimization. “We are a people existing, thriving, surviving, trying. In the end, we’re just all humans, trying to make the best of this life.”

- Date modified: