Coastal collaboration helps improve resilience among remote seaside communities in West Africa

Living in isolated communities on islands and stretches of coastline brings a dependence on the plants and animals at and below the water’s edge. It’s a reality as much for people in West Africa’s vast river deltas as for those in Quebec’s maritime region.

Development programming supported by Global Affairs Canada is linking the 2 remote areas. Projects implemented by the Gaspésie et les Îles CEGEP are helping to improve lives and livelihoods in seaside communities in The Gambia, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau and Senegal through sustainable aquaculture, women’s economic empowerment and coastal ecosystem management there.

“There’s a lot that we can learn from each other,” says Line Bourdages, coordinator of operations in Dakar, Senegal, for the CEGEP. It leads development programming in West Africa alongside a number of local partners and its Quebec School of Fish and Aquaculture (ÉPAQ). While Bourdages notes that the 2 regions have different climates, species and conditions, “we have a lot of expertise in fisheries and shellfish that we’re trying to bring to these remote communities.” The 2 areas also have common problems, from coastal erosion related to sea-level rise to the over-exploitation of their fisheries, she says. “Collaboration is critical to finding solutions.”

Line Bourdages is the coordinator of operations in Dakar, Senegal, for Gaspésie et les Îles CEGEP.

Photo credit: Julie Lépine.

The projects include efforts to restore the mangroves along the region’s coastlines affected by climate change and to help people harvest, process and market the oysters and small ark clams found there. It is also working to strengthen value chains, enhance tourism, draw awareness to the circular economy, promote gender equality and the rights of vulnerable populations and encourage youth participation in economic activities.

A long history of international cooperation

The CEGEP, which has campuses in Carleton-sur-Mer, Gaspé and Grande-Rivière on the Gaspé Peninsula, as well as on the Magdalen Islands, started programming in West Africa in 1998. Its first projects focused on raising awareness of the distant region among people back home. Since then it has helped to construct shellfish processing facilities in remote communities on the coast of Senegal, as well as to encourage other activities, such as ecotourism and women’s entrepreneurship.

A current project called Women’s Governance and Innovation (GEFI) in 3 villages of Senegal’s Saloum Delta focuses on improving the economic, social and environmental development of those communities. Another, called Adaptation of Coastal Populations and Blue Economy (APOCEB), is scaling up the construction of shellfish processing units, with 26 of them being built in isolated communities in The Gambia, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau and Senegal.

A tray of cooked and dried ark clams is ready for packaging at one of the shellfish processing units.

CREDIT: Gaspésie et les Îles CEGEP

Bourdages says the programming depends on local participation, bringing together student researchers, senior academics and local authorities from the region. The projects also mobilize the expertise of teachers from ÉPAQ, who regularly collaborate with those teams on the ground. And in January 2023, a group of 10 natural sciences students from the CEGEP came to do short internships in Senegal to learn about the projects there and get hands-on experience in the field.

“It’s pretty eye-opening to be here,” says Bourdages, who comes from a small town called Maria on Chaleur Bay on the southern shore of the Gaspé. She notes that most of the college’s remote “intervention zones” in West Africa have no Internet, phones or other forms of communication. Some are islands as much as a 6-hour boat ride from the nearest large population centre.

As a physicist who has spent her career researching the advance of climate change, Bourdages today sees first-hand its impact on the coastal communities of West Africa. She also well understands the need for climate adaptation and the benefits of people becoming more resilient.

A critical focus on women

For example, with the decline in the fisheries many of the men have left to pursue employment elsewhere. Women remain behind to be the heads of households and support their families. “We really try to bring efficiency to their work,” Bourdages says. GEFI and APOCEB encourage the women to form groups—for example, so they can seek out financing for further economic opportunities, she explains. “We want these activities to go beyond the project; we don’t want everything to stop when we leave.”

A basket of freshly caught ark clams, ready for processing.

Credit: Gaspésie et les Îles CEGEP

Women are dependent on natural resources for income-generating activities that have been undermined by climate change. Bourdages says the CEGEP projects encourage them to selectively collect shellfish so that only those above a certain size are harvested, leaving the juveniles to grow and reproduce. They clean and prepare them in the shellfish processing units, buildings and open sheds with equipment that is safe and meets commercial standards. The women are given financial training so they can sell their products at a profit, and they are encouraged to diversify their money-making activities into endeavours such as beekeeping or raising chickens “so they do not rely only on a resource that’s in decline,” Bourdages says. And they use the units to process fruit during the “biological resting period”—several rainy months in the middle of the year when shellfish collection is forbidden.

On the island of Niodior, far out in Senegal’s Saloum Delta, the ability to better process the shellfish means the products can fetch a good price, with sales locally and internationally, says Fatou Ndong Sarr, president of a federation of local women’s groups. She explains that sorting and cleaning the shellfish by hand in the past took time; now the work is more efficient and hygienic, with rigorous quality control.

Fatou Ndong Sarr is president of a federation of local women’s groups on the island of Niodior in Senegal.

Credit: Aiza Ndoye

“Women are improving the management not only of the activity but the resource,” she says, which brings influence and power. They have quadrupled the rate they get for their products, “and we’re the ones who set the price,” Sarr points out. The women also better understand the importance of protecting the natural environment, and the processing unit has become an important core for the community. “It brings us together and helps us imagine other solutions,” she comments, adding that having such opportunities is also helping stem the exodus of young people to the city.

A big part of the CEGEP projects is scientific research, Bourdages says: learning about the impact of climate change, the over-exploitation of the fishery and the response of different shellfish to changing salinity, for example. “That’s really important if you want to make informed decisions in the future.”

Understanding the importance of the mangroves

One common denominator among all these communities is the mangrove, which offers important lessons in environmental adaptation. Complex mangrove ecosystems are unique to tidal zones in low coastal regions of tropical countries, developing where land meets sea. The vegetation and animals that live there have adapted to withstand constantly changing conditions, such as tides continually flooding them with sea water and then exposing them to the open air. It’s a fertile but sometimes hostile and fragile area that has been degraded by pollution, silt and an increase in water and land salinity.

Women plant and care for mangrove tree seedlings.

Credit: Gaspésie et les Îles CEGEP

“For all these reasons, the mangrove requires protection,” says Nicolas Mbengue, who is from Senegal and works for the CEGEP as an environmental expert on the APOCEB project.

Mbengue, who specializes in water and forest engineering, says mangroves provide essential habitat for fish, shellfish and other aquatic animals. The coastline of Africa stretching from Senegal to Sierra Leone, referred to as the Southern Rivers, is rich in them. However, they have been decimated by drought and the development of roads and dikes that block their connection with the sea, as well as by logging and clearing for development. This led to a decrease of almost 40% of the mangroves there from 1950 to 1995. Since then, a growing awareness of their ecological importance has led to mangrove protection and restoration programs in the region.

Mbengue says the trees are especially affected by decreased rainfall, which leads to hyper-salinization, and sea-level rise compromises their development. Meanwhile, mangroves can mitigate climate change, given their ability to absorb greenhouse gases and protect the land from salt incursion and coastal erosion, “which contributes to adaptation,” he notes. “The mangrove ecosystem is capital for the fight against climate change.”

A big part of the APOCEB programming is aimed at raising awareness of the importance of the mangroves to communities, he says. Women and youths are trained in reforestation techniques, helping to plant and monitor mangroves in degraded areas. It’s important for people to have the knowledge to continue to look after the mangroves once the CEGEP project is over, he adds. “Communities need to have autonomy.”

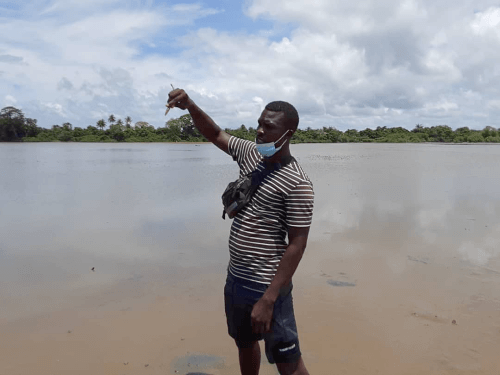

Nicolas Mbengue, who works for the CEGEP as an environmental expert, holds up a sprouted seed produced by the mangrove tree, called a propagule.

CREDIT: Séraphin Diatta

Bringing resilience to coastal populations

Bourdages says raising awareness about climate change and its impacts on coastal populations is a critical step toward improving their resilience. “You need to understand what’s threatening you to be able to resist it—and to overcome it,” she says. “If you don’t prepare for what’s coming or if you’re not aware of what is threatening you, be it coastal erosion or the salinization of the land, what do you have to fight against? You can’t find solutions.”

Yolaine Arseneau, director general of the CEGEP, says it is especially gratifying to see the new products that have been made by women in West Africa with the help of the programming. Some of these were presented last year at a forum on the circular economy on the island of Rubane in Guinea-Bissau’s Bijagós archipelago. It brought together 110 people from 28 villages in the 4 countries where the CEGEP has projects, and included a manifesto written by the women calling for their children to have opportunities for the future.

“I am proud that the CEGEP contributes to improving the quality of life of women, youths and families of this region,” Arseneau says. “We are living a beautiful moment here.”

- Date modified: