Hope and math: Education programs promise opportunity for girls and women in Afghanistan

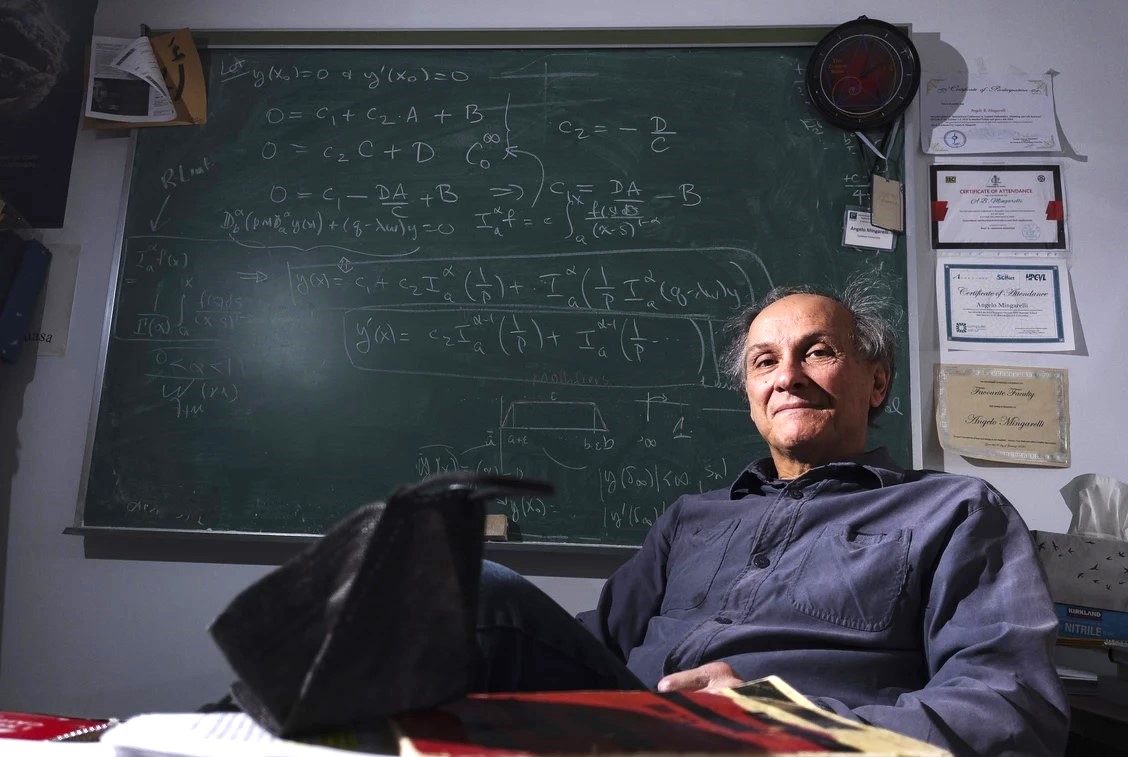

When the Taliban took control of Afghanistan in 2021, Angelo Mingarelli worried about the girls and women in the country who were suddenly unable to go to school.

Now the professor of mathematics at Carleton University in Ottawa is working with a Canadian organization to post his course materials on the web. Beginning this autumn, he will start teaching first-year calculus to those who want to pursue a career in engineering.

Credit: Courtesy of Angelo Mingarelli

“I want to ignite a passion for learning for women in Afghanistan,” says Mingarelli, who’s taught advanced math for more than 45 years and, as the father of 4 grown daughters, understands the importance of education for girls and women. When he found that Canadian Women for Women in Afghanistan (CW4WAfghan) provides a platform for Afghan women to learn remotely, he offered to give the group the Internet resources he had developed during the COVID-19 pandemic and to teach online as a pilot project. “I’m ready to go.”

Mingarelli’s course is one of many CW4WAfghan offerings that support Afghan girls and women—both those in the country and those displaced as refugees—in pursuing educational opportunities, says Murwarid Ziayee, its senior director, based in Calgary. The group began in 1998 to provide quality, gender-equitable education in Afghanistan, says Ziayee, who joined CW4WAfghan in Afghanistan in 2010 and came to Canada in 2018.

She has experienced first-hand the impact of Taliban rule on education for women. Ziayee was studying law and political science at Kabul University in 1996 when the Taliban initially took over, and she was banned from finishing her studies. When the Taliban left 5 years later, she returned to the classroom to complete her degree—although many did not, she notes. “I was lucky to be one of the women to graduate.”

Credit: CW4WAfghan

The country’s “gender apartheid” has economic, developmental and health consequences for women, notes Ziayee, and it could cut off the supply of educated professionals Afghanistan needs. “No country can advance when it holds back women and girls.”

CW4WAfghan offers virtual tools that provide access to education for Afghans in the country and region, called the Darakht-e Danesh Academi (“Knowledge Tree Classroom”). It partnered with Global Affairs Canada on a program called Gender Equality in Teacher Training (GETT) that provided free virtual training on topics such as trauma, digital literacy skills and gender-based analysis to more than 6,000 displaced Afghan educators in countries surrounding Afghanistan. Participants received certificates upon completion of the courses, including one from the University of British Columbia, which provided the trauma module that was adapted and translated for the GETT program.

My TOEFL House, an organization in Rawalpindi, Pakistan, benefited from GETT to deliver English-language, educational and business-studies courses to Afghan refugees, says Sayed Dawood Hussaini, a teacher and co-founder of the organization.

“Before students can take digital classes, we need to train them in areas such as, ‘what is software?’, ‘what is hardware?’, ‘what is an Internet browser?’ There are very basic needs,” he says. “These young people are trauma stricken, without any aim in life. We’ve created classes that offer hope that they can start again and pave the way for new achievements.”

Credit: My TOEFL House

Global Affairs Canada is now providing support to expand the capacity of CW4WAfghan’s online school, which Ziayee says will allow 1,000 girls from grades 7 to 12 to attend class virtually.

The organization also offers free online English-language courses for women and girls in Afghanistan in collaboration with Arizona State University, with more than 15,900 of them so far on the list to take the courses. Ziayee says CW4WAfghan is looking for partnerships with Canadian universities to support women students in Afghanistan and the surrounding region. This can mean accepting them as transfer students, enabling virtual enrollment, waiving application fees or offering financial assistance.

Mingarelli expects his first-year calculus class will have 50 to 100 students to start. “They’ll hear my voice; they’ll see me teach; they’ll take notes, and we’ll go on from there.” He’d like to add a second-year course and believes it would be possible to offer classes to even 10,000 students, “as long as the servers can handle it.”

He notes the pandemic “was an awful time in human history but actually led to a revolution in learning” through the development of digital teachings. His course materials will now benefit women in Afghanistan who are “stuck at home,” much like people were during the COVID-19 crisis. “We know what to do administratively; we know what to do educationally,” he says. In addition to posting his materials online, translated into Farsi, he says it’s critical “to interact with these women. They need to ask you questions live; they need to see your eyes move; they need to see your passion for the subject.”

He feels it’s important for women who complete his course and pass the exam to obtain “microcredits” that are recognized by Carleton University and other institutions. This could be complicated by the fact that the students will not technically be registered, paying tuition or taking classes on Carleton’s server. “There has to be a certain amount of trust from the university,” Mingarelli says. “In the worst-case scenario, I’ll write a certificate for every one of the women that passes my course.”

He’s concerned girls and women in Afghanistan will be dispirited by the lack of career opportunities there. He hopes those in his virtual class will “realize that they’re not alone. They will have their eyes open and say, ‘Okay, there’s a world out there that we can join at some point.’” Mingarelli would also like Carleton to offer some free scholarships for Afghan women to come to Canada and continue their education here.

- Date modified: