Archived information

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

Evaluation of Canada-Haiti Cooperation

2006-2013 - Synthesis Report

January 2015

Table of Contents

- List of Acronyms and Abbreviations

- Executive Summary

- 1.0 Introduction

- 2.0 Country Context and Information on the Cooperation Program

- 3.0 Key Findings

- 4.0 Development Results

- 5.0 Management Principles

- 5.1 Aid Coordination

- 5.2 Efficiency

- 5.3 Performance Management

- 6.0 Conclusions

- 7.0 Lessons

- 8.0 Recommendations

- Annex A: Summary of the Terms of Reference

- Annex B: Methodology

- Annex C: List of Projects Reviewed

- Annex D: List of Documents Reviewed

- Annex E: List of People Interviewed

- Annex F: Summary of Project Ratings by Programming Sector

- Annex G: Summary of Program and Project Ratings by CIDA Division

- Annex H: Summary of Ratings by Criterion and Sector

- Annex I: Humanitarian Assistance–Development Continuum

- Annex J: Follow-up Surveys of Fragile States – Haiti

- Annex K: Findings on Principles for Engagement in Fragile States

- Annex L: Guidelines for Classifying Findings in the Literature Review

- Annex M: Management Response

Annex H: Summary of Ratings by Criterion and Sector

Table 15: Relevance of all sample projects by sector

Efficiency/Economy of all sample projects by sector - Alternative Text

| Sector | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health | Education | Governance | Sustainable economic growth and food security | Reconstruction and development | Total | |||

| Q1_Relevance _mean_recode | Highly unsatisfactory | Count | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Unsatisfactory | Count | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Moderately satisfactory | Count | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Satisfactory | Count | 3 | 4 | 8 | 3 | 3 | 21 | |

| Highly satisfactory | Count | 8 | 5 | 3 | 8 | 0 | 24 | |

| Not documented | Count | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Total | Count | 12 | 9 | 11 | 12 | 3 | 47 | |

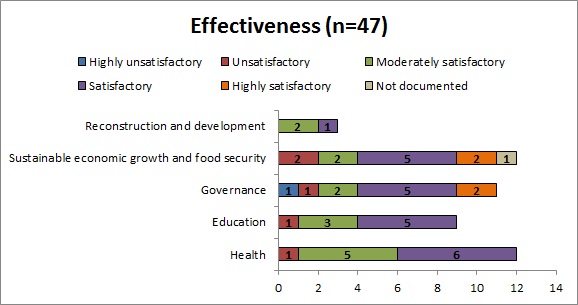

Table 16: Effectiveness of all sample projects by sector

Efficiency/Economy of all sample projects by sector - Alternative Text

| Sector | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health | Education | Governance | Sustainable economic growth and food security | Reconstruction and development | Total | |||

Q2_Effectiveness | Highly unsatisfactory | Count | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Unsatisfactory | Count | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 5 | |

| Moderately satisfactory | Count | 5 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 14 | |

| Satisfactory | Count | 6 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 22 | |

| Highly satisfactory | Count | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 4 | |

| Not documented | Count | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Total | Count | 12 | 9 | 11 | 12 | 3 | 47 | |

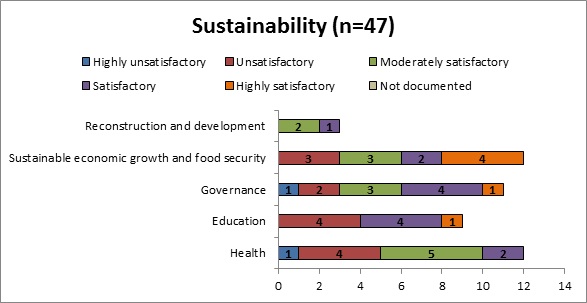

Table 17: Sustainability of all sample projects by sector

Efficiency/Economy of all sample projects by sector - Alternative Text

| Sector | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health | Education | Governance | Sustainable economic growth and food security | Reconstruction and development | Total | |||

| Q3_Sustainability _res_obt_mean_recode | Highly unsatisfactory | Count | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Unsatisfactory | Count | 4 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 13 | |

| Moderately satisfactory | Count | 5 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 13 | |

| Satisfactory | Count | 2 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 13 | |

| Highly satisfactory | Count | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 6 | |

| Not documented | Count | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total | Count | 12 | 9 | 11 | 12 | 3 | 47 | |

Table 18: Gender equality of all sample projects by sector

Gender equality of all sample projects by sector - Alternative Text

| Sector | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health | Education | Governance | Sustainable economic growth and food security | Reconstruction and development | Total | |||

| Q4_Effic_legal_homes _femm_mean_recode | Highly unsatisfactory | Count | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Unsatisfactory | Count | 4 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 13 | |

| Moderately satisfactory | Count | 5 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 13 | |

| Satisfactory | Count | 2 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 13 | |

| Highly satisfactory | Count | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 6 | |

| Not documented | Count | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total | Count | 12 | 9 | 11 | 12 | 3 | 47 | |

Table 19: Environmental sustainability of all sample projects by sector

Environmental sustainability of all sample projects by sector - Alternative Text

| Sector | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health | Education | Governance | Sustainable economic growth and food security | Reconstruction and development | Total | |||

| Q4_Effic_environ _mean_recode | Highly unsatisfactory | Count | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Unsatisfactory | Count | 4 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 6 | |

| Moderately satisfactory | Count | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 9 | |

| Satisfactory | Count | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 9 | |

| Highly satisfactory | Count | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 6 | |

| Not documented | Count | 3 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 14 | |

| Total | Count | 12 | 9 | 11 | 12 | 3 | 47 | |

Table 20: Coherence of all sample projects by sector

Coherence of all sample projects by sector - Alternative Text

| Sector | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health | Education | Governance | Sustainable economic growth and food security | Reconstruction and development | Total | |||

| Q5_Coherence _mean_recode | Highly unsatisfactory | Count | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Unsatisfactory | Count | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 5 | |

| Moderately satisfactory | Count | 4 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 16 | |

| Satisfactory | Count | 3 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 14 | |

| Highly satisfactory | Count | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | |

| Not documented | Count | 4 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 7 | |

| Total | Count | 12 | 9 | 11 | 12 | 3 | 47 | |

Table 21: Efficiency/Economy of all sample projects by sector

Efficiency/Economy of all sample projects by sector - Alternative Text

| Sector | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health | Education | Governance | Sustainable economic growth and food security | Reconstruction and development | Total | |||

| Q9_Efficience_mean_recode | Highly unsatisfactory | Count | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| Unsatisfactory | Count | 1 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 8 | |

| Moderately satisfactory | Count | 0 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 8 | |

| Satisfactory | Count | 6 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 17 | |

| Highly satisfactory | Count | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Not documented | Count | 2 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 9 | |

| Total | Count | 12 | 9 | 11 | 12 | 3 | 47 | |

Table 22: Aid effectiveness principles of all sample projects by sector

Aid effectiveness principles of all sample projects by sector - Alternative Text

| Sector | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health | Education | Governance | Sustainable economic growth and food security | Reconstruction and development | Total | |||

| Q6_Princ_effic _laide_mean_recode | Highly unsatisfactory | Count | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| Unsatisfactory | Count | 1 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 8 | |

| Moderately satisfactory | Count | 0 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 10 | |

| Satisfactory | Count | 6 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 17 | |

| Highly satisfactory | Count | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Not documented | Count | 2 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 7 | |

| Total | Count | 12 | 9 | 11 | 12 | 3 | 47 | |

Table 23: Performance management of all sample projects by sector

Performance management of all sample projects by sector - Alternative Text

| Sector | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health | Education | Governance | Sustainable economic growth and food security | Reconstruction and development | Total | |||

| Q7_Gest_rende _mean_recode | Highly unsatisfactory | Count | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Unsatisfactory | Count | 3 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 15 | |

| Moderately satisfactory | Count | 2 | 1 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 12 | |

| Satisfactory | Count | 5 | 5 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 13 | |

| Highly satisfactory | Count | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 5 | |

| Not documented | Count | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Total | Count | 12 | 9 | 11 | 12 | 3 | 47 | |

Table 24: Principles for International Engagement in Fragile States of all sample projects by sector

Principles for International Engagement in Fragile States of all sample projects by sector - Alternative Text

| Sector | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health | Education | Governance | Sustainable economic growth and food security | Reconstruction and development | Total | |||

| Q8_Princ_lengage _intern_mean_recode | Highly unsatisfactory | Count | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Unsatisfactory | Count | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3 | |

| Moderately satisfactory | Count | 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 14 | |

| Satisfactory | Count | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 19 | |

| Highly satisfactory | Count | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 8 | |

| Not documented | Count | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | |

| Total | Count | 12 | 9 | 11 | 12 | 3 | 47 | |

Table 25: Rating of all sample projects by criterion

Rating of all sample projects by criterion - Alternative Text

| Efficiency/Economy | Principles for Engagement in Fragile States | Performance Management | Aid Effectivenesse | Coherence | Environmental Sustainability | Gender Equality | Sustainability | Effectiveness | Relevance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Highly unsatisfactory | 3 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Unsatisfactory | 6 | 3 | 15 | 8 | 5 | 6 | 10 | 13 | 5 | 0 |

| Moderately satisfactory | 6 | 14 | 12 | 10 | 16 | 9 | 7 | 13 | 14 | 1 |

| Satisfactory | 17 | 19 | 13 | 17 | 14 | 9 | 18 | 13 | 22 | 21 |

| Highly satisfactory | 4 | 8 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 24 |

| Not documented | 11 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 7 | 14 | 7 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

Annex I: Humanitarian Assistance - Development ContinuumFootnote 42

Summary of Humanitarian Issues

In the aftermath of the earthquake, more than two million people required emergency food aid in the areas hardest hit, which included Port-au-Prince, Jacmel and Léogâne. Destroyed or damaged schools totalled 87% in Port-au-Prince, 88% in Jacmel and up to 96% in Léogâne. Support for the agricultural sector, activities involving food or cash for work, and education support were essential to support those affected in the three months that followed the earthquake.

After the earthquake, insecurity became a major concern. Infrastructure and police facilities were damaged or simply destroyed. In human terms, the police saw its members injured or killed by the earthquake, thus decreasing the workforce. Gang members and other violent criminals escaped from prison, heightening the insecurity. In this context, it was of vital importance to build the capacity of the Haitian National Police to maintain order and to ensure a visible and credible police presence. In many cases, however, the reality was that the police did not have the means to do their job.

In July 2010, 1.5 million displaced persons lived in camps. By the end of 2010, some 1.3 million people still lived at over 1,300 makeshift sites in Port-au-Prince, Jacmel and Léogâne, in the Department of Artibonite and with host families outside the capital.

Immediately after the earthquake, Canada’s response included the following:

- Some 56 specialists were deployed from DFAIT, CIDA, Citizenship and Immigration Canada (CIC), Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA), Correctional Service Canada (CSC) and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), including search and rescue technicians, medical and logistical staff, engineers, and experts in identifying victims of humanitarian emergencies and disasters.

- Canada deployed 19 humanitarian technical experts to support humanitarian agencies in the field, including 10 Canadian medical staff supporting the CIDA-funded Canada-Norwegian Red Cross joint field hospital.

- Canadian Forces (CF) members were deployed, including Disaster Assistance Response Team (DART) medical staff and field hospitals, personnel, warships and strategic air transportation. Some 2,046 CF members were deployed in Haiti as part of Operation Hestia.Footnote 43

- After the earthquake, Canada strengthened its cooperation with MINUSTAH by contributing twice the number of troops to Operation Hamlet, the CF mission underway to support MINUSTAH. Ten staff officers were deployed until March 2011.

Canada’s Whole-of-Government Approach

The Evaluation of CIDA’s Humanitarian Assistance (CIDA, 2012b) reviewed the working relationships among CIDA divisionsFootnote 44 and among the departments involved.

In the hours that followed the earthquake, DFAIT convened the Interdepartmental Task Force on Natural Disasters Abroad to coordinate Canada’s response to this catastrophic event. Steered by Foreign Affairs, the Task Force encompassed representatives from other key departments and agencies, including CIDA, the Department of National Defence (DND), the Privy Council Office (PCO) and Citizenship and Immigration Canada (CIC).

Internal and external stakeholders generally regarded Canada’s intervention after the 2010 earthquake as a conclusive example of whole-of-government coordination in Ottawa. This conclusion was confirmed by the post-intervention analysis commissioned by DFAIT in the months following the disaster (McGill, 2010). This analyses highlighted many positive aspects of the coordination of Canada’s intervention, including the role played by the Interdepartmental Task Force, the deployment of the Interdepartmental Strategic Support Team in Haiti, and the contribution of liaison officers responsible for political and humanitarian affairs.

The Task Force’s whole-of-government coordination was peer-evaluated as highly effective. The key was ongoing communication among the departments involved. Communication was ongoing, and objectives were clearly understood by all concerned. Moreover, a government-wide task force was established, and its members met twice daily for a long period during the critical phase of the intervention. This event demonstrated that it is possible to ensure cohesion and coordination within and among departments in Ottawa, by showing flexibility and maintaining dialogue. CIDA was deemed to be a credible, useful, and very supportive participant in the interdepartmental coordination process.

However, the analysis also highlighted areas for improvement. Thus, it noted the need for earlier determination of the marshalling of military resources to be used. Planning processes ought to have been synchronized among DFAIT, CIDA and DND. Joint training should have been organized on accepted best practices in humanitarian activities. According to the report, this would have contributed to a shared understanding of the respective corporate cultures, and greater efficiency and effectiveness.

The analysis also showed that standard operating procedures were not as well known in the departments as they could have been. These procedures should clearly state the importance of the whole-of-government approach in Canada’s framework for action, to ensure successful planning and implementation of response to natural disasters. These procedures should also state the Interdepartmental Task Force’s role in establishing the whole-of-government position and developing recommendations to Ministers. In situations that require the deployment of the Canadian Forces, standard operating procedures are a key tool in ensuring effective intervention and a degree of continuity.

Haitian and international partners praised Canada for its timely intervention, its effective response, and the clear impact of Canada’s contributions (financial resources and personnel deployed in Haiti). On June 14, 2010, the Interdepartmental Task Force received the Public Service Award of Excellence for its "Exemplary Contribution Under Extraordinary Circumstances” (TBS, 2010).

Through its humanitarian response to the earthquake that shook Haiti in January 2010, CIDA:

- Contributed to the provision of emergency food aid to 4.3 million Haitians; water and sanitation services to 1.3 million Haitians; emergency and temporary housing to 370,000 families.

- Constructed 3,200 transitional shelter units in Port-au-Prince, Léogâne and Jacmel (2010-2011).

- Vaccinated 60,000 children against common diseases (2010-2011).

- Enabled 85 percent of the affected population to have access to cholera treatment and/or cholera treatment centres (2010-2011) (CIDA, 2012b).

Transition from Emergency to Development Assistance

CIDA did not have a specific strategy to guide its activities in the transition from humanitarian (emergency) to development assistance. However, CIDA’s post-earthquake initiatives were based on plans developed by Haitian authorities and the international community, especially the Interim Haiti Recovery Commission (IHRC) and Haiti’s Action Plan for National Recovery and Development (PARDN).

At a UN International Donors’ Conference on March 31, 2010, Canada announced $400 million for recovery, rehabilitation, and reconstruction programs in Haiti. Haiti is one of the few countries that have benefited from such Canadian funding. However, the corporate Evaluation of CIDA’s Humanitarian Assistance concluded that the lack of corporate coordination and integration mechanisms limited opportunities for synergy and complementarity between humanitarian assistance and development programs. The current evaluation also found that a strategy would have helped define activities more effectively, especially in the area of reconstruction.

Rapid Recovery

IHA Directorate programming includes rapid recovery activities, to the extent that they directly relate to providing immediate relief. For example, Canada supported the UNDP-managed removal of debris in Haiti, making it easier to route humanitarian assistance, while contributing to the rapid recovery of those affected by the earthquake. CIDA also supported the relocation of internally displaced persons camped in Champ de Mars, in the heart of the Haitian government’s administrative area. Moreover, once the humanitarian crisis had passed, several development projects were reoriented to meet the immediate needs of communities. The various data sources, especially interviews with key respondents, showed that all parties were highly satisfied with the support provided, thanks to the flexibility shown in allocating funds and the timeliness of the decision-making process.

Reconstruction

The special reconstruction appeal, totalling nearly $30 million, managed by Partnerships with Canadians Branch (PWCB), was not designed for development purposes but for rapid recovery. Moreover, reconstruction initiatives were largely beyond the scope of PWCB and NGOs, apart from risk mitigation activities in which several NGOs had some experience. The chosen approach created numerous problems for all stakeholders.

Expected outcomes were achieved by both PWCB reconstruction and recovery projects reviewed as part of this evaluation. However, one of them was a development project (Desarmes vocational training school) While relevant to the community in which it was implemented, the project would not have been approved so fast if it had been subject to clear guidelines for what could be deemed a reconstruction project (in terms of the emergency assistance-development continuum).

Apart from the PWCB program, the bilateral program supported a number of reconstruction projects, some of which were underway at the time of the evaluation. As mentioned, the evaluation reviewed the Champ de Mars project. Phase I met expectations in terms of relevance, effectiveness and coherence. Phase II, which involved rebuilding a neighbourhood, was just getting started at the time of the evaluation, and it was too soon to judge its effectiveness. However, the selected partners – UNDP, UNOPS, and the ILO – have in-depth experience in this sector. According to the available data, the project had established sound foundations, so that conclusive results could be expected.

According to key respondents, government capacity building was part of the approach implemented under the leadership of theUnité de Construction de Logements et de Bâtiments Publics (UCLBP) [public housing and building construction unit]. All key respondents involved in this project felt that Canada had taken a risk, which could have cost its reputation dearly if it had failed. However, the success achieved had leverage and encouraged other technical and financial partners (TFPs) to follow suit.

Working Relationships Among Corporate Divisions

At CIDA (prior to the DFATD merger), humanitarian response quickly became a priority for the entire organization. Resources were mobilized from all sectors of CIDA to participate in an internal task force to respond to the emergency situation. The usual procedure and approval processes were followed, but directors general could consult directly with the President and the Minister, so that it was easier to make decisions. Program development resources were reallocated to fund rapid recovery and reconstruction priorities.

The Corporate Evaluation of CIDA’s Humanitarian Assistance found that, although field personnel had a mandate to represent all of CIDA’s corporate divisions abroad, they did not have a mandate that would allow them to participate in managing humanitarian assistance programs. They noted that they had not received any clear directive or instruction from Headquarters regarding humanitarian assistance and the extent to which they could and should contribute to humanitarian assistance programs.

The Corporate Evaluation of CIDA’s Humanitarian Assistance concluded that CIDA did not establish a consensus on how to manage the coordination and integration of humanitarian assistance and development, especially regarding programs in prolonged crisis situations. Other donor countries have humanitarian assistance policies and strategies calling for activities related to emergency planning, rapid recovery, and transition between humanitarian assistance programs and development programs.

The Corporate Evaluation of CIDA’s Humanitarian Assistance also recommended the development of a whole-of-government humanitarian assistance policy and a strategy based on an integrated approach, which would aim to support risk prevention and mitigation, as well as recovery and the transition to development. This would provide a framework for the integration of humanitarian assistance programs and development programs, with a view to developing a standard procedure for intervention in developing countries after a natural disaster.

This framework would also allow better definition of the roles and responsibilities of Headquarters and field personnel regarding the execution of humanitarian assistance programs and strategic commitments (that is, mandate, policy and support). It would serve as a foundation for a more stringent system of accountability and reporting. According to interviews with key respondents, a strategy has been prepared for study, but it has been put on hold owing to the CIDA-DFAIT merger.

Annex J: Follow-up Surveys of Fragile States – Haiti

Principles: Take context as the starting point.

Summary of Results - 2010: Consensus was reached on the overall vision, reflected in Haiti’s national growth and poverty reduction strategy paper (GPRSP). However, Haitian and international stakeholders have not yet been able to identify shared priorities. This may decrease coherence and thus the scope of international engagement. Moreover, the situation is seen in a relatively static manner, whereas the situation has greatly evolved since 2006.

Summary of Results - 2011: Few joint analyses have been done that can help to set international assistance priorities. The international community generally seems to be content to do more but not necessarily better.

Principles: Do no harm.

Summary of Results - 2010: It was noted that there was a risk of weakening the Government through overuse of parallel implementation mechanisms, and the aid concentration in certain geographic areas, which could reinforce what has been called the exclusion of the rural majority. Major differences in salary between local and international employees contribute to brain drain.

Summary of Results - 2011: There is a contradiction between institutional capacity building objectives and the reality of the international presence, which indirectly encourages brain drain and the marginalization of institutions.

Principles: Focus on state-building as the central objective.

Summary of Results - 2010: It was noted that the Haitian National Police had improved its operations. Overall, however, the Government still has a poor capacity to absorb aid and to provide services. Government capacity building support focuses on the executive branch of the central government, whereas it has been recognized that the “social contract is weak”, and the Government’s presence is limited in several regions.

Summary of Results - 2011: The Government’s role is not the focus of enough policy dialogue to achieve consensus between donors and the Government itself.

Principles: Prioritize prevention.

Summary of Results - 2010: The situation has improved, thanks to massive investment in prevention (especially MINUSTAH). However, little consideration is still given to the social and economic aspects of prevention. Consensus has been reached on the need to address this principle comprehensively (youth unemployment, education, and so on). Security sector reform has not yet produced results. (The reform of the justice system has been delayed.)

Summary of Results - 2011: Investment to make Haiti and its people less vulnerable is not equal to the challenge.

Principles: Recognize the links between political, security and development objectives.

Summary of Results - 2010: It was noted that there was a lack of interdepartmental and inter-sectoral approaches around clearly identified priorities. However, participants noted that support for Parliament remains just as strong, as do relations among the three branches of government.

Summary of Results - 2011: The approach to security is not suited to the reality of Haiti. The international community must promote constructive dialogue among the three branches of government.

Principles: Promote non-discrimination as a basis for inclusive and stable societies.

Summary of Results - 2010: Progress on gender issues has been applauded, but it was noted that the rural population, the unemployed, and youth were paid insufficient attention.

Summary of Results - 2011: A growing segment of the population is or feels excluded (youth, exploited minors or persons with disabilities).

Principles: Align with local priorities in different ways in different contexts.

Summary of Results - 2010: The Paris Declaration’s target was reached. However, there could be deeper textment, especially at the sectoral level and with priorities identified at the regional level.

Summary of Results - 2011: Implementation procedures are not being adequately discussed with the Government, whereas they play a key role in program sustainability. Budget support remains well below the Government’s needs.

Principles: Agree on practical coordination mechanisms between international actors.

Summary of Results - 2010: Coordination is good in some sectors and poor in others. The high number of sectoral groups poses an additional challenge.

Summary of Results - 2011: It is necessary to revitalize mechanisms that were starting to prove their utility before the earthquake, and would ensure better coordination of development partners under the Government’s leadership.

Principles: Act fast … but stay engaged long enough to give success a chance.

Summary of Results - 2010: Rapid response and risk mitigation capacity was deemed insufficient. Moreover, there is a lack of long-term commitment in some sectors.

Summary of Results - 2011: The sustainability and predictability of international support remains problematic. There has not been a planned, gradual transition from the emergency phase to a stabilization and development phase.

Principles: Avoid pockets of exclusion.

Summary of Results - 2010: Assistance is concentrated in the south of Haiti. This is partly justified but, over time, it may contribute to a deeper feeling among rural Haitians that they have been left out.

Summary of Results - 2011: The international community must continue to show willingness to deconcentrated government services and to decentralize Haiti. Otherwise, there may be increased pockets of exclusion and division between urban and rural areas.

Annex K: Findings on Principles for Engagement in Fragile States

The ten principles for international engagement in fragile states are as follows:

Principles for Engagement in Fragile States

- Take context as the starting point.

- Do no harm.

- Focus on state-building as the central objective.

- Prioritize prevention.

- Recognize the links between political, security and development objectives.

- Promote non-discrimination as a basis for inclusive and stable societies.

- Align with local priorities in different ways in different contexts.

- Agree on practical coordination mechanisms between international actors.

- Act fast … but stay engaged long enough to give success a chance.

- Avoid pockets of exclusion.

The evaluation reviewed the extent to which Canada adhered to these principles in its cooperation with Haiti. The evaluation looked at all of the principles for international engagement in fragile states, but more closely examined the extent to which Canadian cooperation considered Principle 1: Take context as the starting point; Principle 3: Focus on state-building as the central objective;and Principle 9: Act fast … but stay engaged long enough to give success a chance. To complement its analysis, the evaluation used the findings of monitoring surveys of the principles for good international engagement in fragile states.

Canada began implementing the OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC) Principles for Good International Engagement in Fragile States in Haiti in 2005-2006, and formally subscribed to them in April 2007 (DAC, 2007).

It is important to note that, except in 2007, annual reports during the review period did not mention the Principles for Engagement in Fragile States. The evaluation found no conclusive evidence in reports, strategies, third-party evaluations or interviews with key respondents that the Principles were considered. The first survey was produced in 2010, the year of the earthquake, and stakeholders undoubtedly had other concerns. However, CIDA might have been expected to mention the monitoring surveys in its annual reports for 2011 and 2012.

The Monitoring Surveys of the Principles of Engagement in Fragile States offer a mixed assessment of the international community’s performance and identified weaknesses for all of the Principles. The surveys indicated that there is still a long way to go. The findings of these surveys should provide food for thought for Canada’s future cooperation strategy with Haiti.

The monitoring surveys contain few specific data by donor country. Rather, they analyze the overall practices of countries and development agencies. However, the 2011 survey reports data gathered from technical and financial partners, focusing mainly on Principle 3, Focus on state-building as the central objective. In light of the evaluation’s findings, some observations can be made about Canada’s cooperation approach in relation to the conclusions of the 2010 and 2011 monitoring surveys.

Principle 1 – Take context as the starting point. The monitoring surveys concluded that Haiti’s national Growth and Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper (GPRSP) created and reflected a consensus in terms of overall vision, but Haitian and international stakeholders failed to identify shared priorities.

Canada played an active role in the coordination process, which aimed to adopt a more coordinated approach among international agencies, and which included the Government of Haiti in identifying priorities and making decisions. This was especially evident in the health sector and in establishing a joint framework for the reconstruction of Haiti following the earthquake. The project review and interviews with key respondents resulted favourable rating for this principle. Generally speaking, project relevance implies fairly specific knowledge of context.

Principle 2 – Do no harm.

The 2010 and 2011 monitoring surveys noted that overuse of parallel implementation mechanisms risked weakening the Government. Moreover, concentrating aid in certain geographic areas might reinforce what was called “the exclusion of the rural majority”. The surveys noted that significant differences in salary between local and international staff contributed to qualified staff leaving their jobs.

Canada cooperation contributed to these various problems. With regard to geographic concentration, for example, Canadian cooperation was mainly concentrated in southern Haiti and Artibonite. However, efforts were made to avoid duplication by analyzing the geographic distribution of programs by other donors and the United Nations.

Canada contributed to the use of parallel implementation mechanisms, which can both weaken the Government and raise salaries. One of the causes of the problem documented in this evaluation is the lack of confidence among TFPs in the Government of Haiti’s management systems, governance practices and lack of transparency. As a result, Canada and other TFPs were reluctant to go through government mechanisms or to provide budget support to the Government of Haiti.

This view is shared by many university researchers and members of the Haitian government. For example, in a speech given during a visit to Canada in 2008, a Haitian minister argued that, in his opinion, despite efforts made by the Haitian government to improve the management of resources from the international community, and despite principles set out in the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness, traditional donors have not invested sufficiently in the consolidation of the Haitian State, and this has jeopardized the sustainability of initiatives (Baranyi, 2010).

Principle 3 – Focus on state-building as the central objective. The project review and interviews with key respondents resulted in a quite favourable rating for Principle 3, based on the fact that, in general, capacity building of government and civil society lay at the heart of Canada’s cooperation strategy, to allow Haitians to exercise their fundamental rights. As highlighted in Section 3, Canada supported initiatives to strengthen public administration and governance, especially in the health and education sectors, and democratic institutions and processes, such as Parliament, the civil registry, and the conduct of elections.

The evaluation identified many examples of projects designed to strengthen, not only the central mechanisms of ministries, but also those of departments, municipalities and community-based organizations. Canada also played a key role in strengthening the Haitian National Police (HNP), by supporting the establishment of a police academy, and by providing training and direct support for the HNP, to improve its day-to-day practices and management. Poor management capacity, and inadequate human and financial resources, were frequently cited to explain difficulties or lack of progress in initiatives.

The 2011 survey noted that, based on a number of indicators, Canada had made some progress since 2007. For example, the percentage of technical cooperation coordinated with Haitian programs rose from 0% in 2007 to 21% in 2010. By comparison, countries such as the United States and Spain, the two other countries with the largest budgets for Haiti, achieved full coordination with Haitian programs in 2010. As for the percentage of missions coordinated between partners, Canada went from 7% in 2007 to 41% in 2010. The percentage was 11% for Spain and 100% for the United States. In terms of the program-based approach, Canada went from 0% in 2007 to 57% in 2010.

Principle 4 – Prioritize prevention. The surveys noted that the situation had improved, thanks to massive investment in prevention (especially by MINUSTAH), but little consideration continued to be given to the social and economic aspects of prevention. It was also noted that reform of the security sector had not yet yielded results (reform of the justice system had been delayed), and investment to make Haiti and its people less vulnerable had not met expectations.

The bulk of the MINUSTAH contingent came from Brazil. However, Canada provided political, financial, and logistical support for MINUSTAH throughout the period. Canada was, in fact, one of the main sponsors of the UN force to minimize violence after President Aristide left Haiti in 2004. Since 2004, the UN force has succeeded in stabilizing Haiti, reducing gang violence, and allowing the conduct of peaceful elections. However, the approach has its detractors, including large segments of the people of Haiti.

MINUSTAH’s objective of ensuring security is criticized by those who feel that it has heightened police presence, instead of addressing vast social and economic problems, and making efforts to combat the deterioration of infrastructure, unemployment and widespread poverty.Footnote 45 Moreover, MINUSTAH troops themselves were accused of engaging in sexual violence, among other things, and of causing the cholera epidemic in October 2010. Canada thus found itself in the midst of controversy.

Principle 5 – Recognize the links between political, security and development objectives. The surveys indicated that the security approach was not suited to the reality of Haiti, and that the international community should promote constructive dialogue among the three branches of government.

As mentioned earlier, Canadian cooperation has supported initiatives to strengthen Parliament and the justice system. The 2006-2007 annual reports mention direct support for the Prime Minister’s Office after elections were held. However, it does not seem that Canada has developed a comprehensive approach in this regard. As noted by the survey, moreover, a more concerted approach would be desirable between the Government of Haiti and the international community.

Principle 6 – Promote non-discrimination as a basis for inclusive and stable societies. The surveys noted that progress on gender issues was applauded, but highlighted a lack of attention to rural Haitians, the unemployed, and youth.

As this evaluation showed, where their contribution to gender equality was documented, two thirds of Canada-funded sample projects had a positive impact. Canadian NGOs achieved good results, owing to their extensive experience in this regard. Cooperation also targeted rural Haitians, thanks to agriculture and food security projects, as well as young women and men, through vocational training projects and the promotion of economic growth. However, the needs far exceeded the available amounts.

Principle 7 – Align with local priorities in different ways in different contexts. The surveys noted that implementation procedures were not adequately discussed with the Government, whereas they play a major role in program sustainability. Budget support remains far less than the Government’s needs.

Canadian cooperation did not go in the direction of budget support, and there remained no procurement using Haitian mechanisms. It is important to note that the vast majority of donors were reluctant to provide budget support to the Government of Haiti, because of fiduciary risks owing to a lack of transparency. According to key stakeholders, nothing ever came of discussions with Haitian authorities regarding the terms and conditions for such support. As a result of these factors, Canada mitigated risks by implementing major projects through United Nations agencies, such as the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), UNFPA, UNOPS, and UNICEF. The 2011 survey noted that Canada relied heavily on the United Nations system to implement its initiatives. Between 2007 and 2011, the number of coordination units paralleling UN projects increased from 16 to 38.

Principle 8 – Agree on practical coordination mechanisms between international actors. The monitoring surveys noted the need for better coordination among development partners, under the Government’s leadership, as initiated prior to the earthquake.

Canada participated in international coordination efforts by supporting the Ministry of Planning and Foreign Cooperation (MPCE), as well as strategies giving ministerial executives a central role in development initiatives, especially in the health and education sector. Although Canadian cooperation and the international community sought to include the Government of Haiti in making decisions about the humanitarian efforts and the recovery and reconstruction phases, the scope of the many international stakeholders’ human and financial resources greatly exceeded the capacities of the Government of Haiti, weakened by the enormous loss of human lives and the destruction of infrastructure.

For example, the United Nations Special Envoy for Haiti said that it was virtually impossible for the Government to lead the enormous task of making the transition to recovery after the earthquake, since more than 99 percent of relief funds had bypassed Haitian public institutions, and the Government of Haiti had received 15 percent to 21 percent of available funding for long-term reconstruction assistance.Footnote 46 To date, only the European Union and the World Bank have provided budget support to the Government of Haiti.

Principle 9 – Act fast… but stay engaged long enough to give success a chance. The monitoring surveys concluded that rapid response and risk mitigation capacity had been deemed insufficient. Moreover, there was a lack of long-term commitment in some sectors. It was also noted that the sustainability and predictability of international support remained problematic, and that there had not been a planned, gradual transition from the emergency phase to a stabilization and development phase.

It is clear that Canada has made a long-term commitment to Haiti, and has responded quickly and appropriately to natural disasters. As seen earlier in this report, Canada quintupled its pre-2006 annual contribution to a yearly average of about $100 million, and added $400 million to help Haiti to get back on its feet after the earthquake. However, the Government of Canada announced, in January 2013, that the allocation of funds for new projects in Haiti has been suspended.

The evaluation clearly showed that Canadian cooperation has contributed to progress in health, especially by decreasing maternal and child mortality, and in education by helping to increase access to primary education. Canadian cooperation has helped to stabilize food security. Timely and targeted governance support made it possible to hold acceptable elections twice, in 2006 and in 2011.

Despite investment by the international community, however, very little progress was made on human development indicators from 2006 to 2012. Much remains to be done to slow loss of qualified staff and capital flight, and to ensure enough political stability so social and economic development can finally begin. Canadian assistance should eventually take the form of budget support. In 2013, however, conditions had not yet been met to allow confident adoption of this approach.

Principle 10 – Avoid pockets of exclusion. The monitoring surveys noted that aid was concentrated in southern Haiti, and that this could eventually contribute to a deeper feeling among rural Haitians that they had been excluded. The monitoring surveys also noted that deconcentration efforts should continue. Canadian cooperation was fairly well balances in this regard by its support for decentralization efforts and strengthening the delivery of services close to the grassroots level in areas where it was active (such as poor neighbourhoods and rural areas). Investment by Canadian cooperation was also fairly well balanced in terms of support for central, regional, and local institutions.

New Deal for Engagement in Fragile States

On November 30th, 2011, Busan hosted the 4th High Level Forum on Aid Effectiveness. During this forum, the New Deal for Engagement in Fragile States was presented and endorsed. The New Deal was developed by the members of the International Dialogue for Peacebuilding and Statebuilding, comprised of of the g7+ group of 19 fragile and conflict-affected countries, development partners, and international organizations.

The New Deal proposes a framework for building peaceful states. It creates change by using the peacebuilding and statebuilding goals as a guide for working in fragile and conflict-affected states. It focuses on new ways of engaging and putting countries in the lead of their own pathways out of fragility, and building mutual trust and strong partnerships. As DFATD moves forward with new programming in Haiti, it will be important to consider criteria from the "New Deal for Engagement in Fragile States.”

Annex L: Guidelines for Classifying Findings in the Literature Review

1. Relevance

Criterion/Question: Q1. To what extent do the activity’s development objectives meet the requirements of target groups and the needs of the people of Haiti?

(1) Highly unsatisfactory: Key aspects of program or project activities and results did not meet the needs and priorities of the target group and the population at large.

(2) Unsatisfactory: There is clearly a gap between the project / initiative’s activities and results, and the target group’s needs and priorities.

(3) Moderately unsatisfactory: The project/initiative’s activities and results meet some of the target group’s needs and priorities.

(4) Satisfactory: The project/initiative’s activities and results meet 50% or more of target group requirements and the needs of the people of Haiti.

(5) Highly satisfactory: The project considers needs and is designed to meet needs and priorities (whether it is successful or not).

Criterion/Question: 1.1 Were projects/initiatives implemented by CIDA compatible with the needs identified by the Government and civil society in Haiti? (Indicators 1.1.1 and 1.1.2)

(1) Highly unsatisfactory: The project/initiative’s activities are not all in line with the priorities of the Government of Haiti or civil society, or with the Millennium Development Goals.

(2) Unsatisfactory: A large share (50% or more) of the CIDA-funded project is not in line with the priorities of the Government of Haiti or civil society, or the Millennium Development Goals, but there is no evidence that they are contrary to these priorities.

(3) Moderately unsatisfactory: 50% or more of the CIDA-funded project is in line with the priorities of the Government of Haiti or civil society, and the Millennium Development Goals.

(4) Satisfactory: Most (75%) CIDA-funded project activities are in line with the priorities of the Government of Haiti or civil society, and the Millennium Development Goals.

(5) Highly satisfactory: All or almost all CIDA-funded project activities are in line with the priorities of the Government of Haiti or civil society, and the Millennium Development Goals.

Criterion/Question: 1.2 Were the objectives and priorities of CIDA-funded initiatives compatible with the Government of Canada’s priorities and CIDA’s overall strategic priorities? (Indicator 1.2.1)

(1) Highly unsatisfactory: The objectives and priorities of CIDA-funded initiatives were not all compatible with the Government of Canada’s priorities and CIDA’s overall strategic priorities.

(2) Unsatisfactory: A large share (25% or more) of the objectives and priorities of CIDA-funded initiatives are not compatible with the Government of Canada’s priorities and CIDA’s overall strategic priorities.

(3) Moderately unsatisfactory: 50% or more of CIDA-funded initiatives are in line with the Government of Canada’s priorities.

(4) Satisfactory: Most of the objectives and priorities of CIDA-funded initiatives (75%) are in line with the Government of Canada’s priorities and CIDA’s overall strategic priorities.

(5) Highly satisfactory: All of the objectives and priorities of CIDA-funded initiatives are in line with the Government of Canada’s priorities and CIDA’s overall strategic priorities.

2. Effectiveness

Criterion/Question: Q2. To what extent did CIDA achieve expected outcomes in Haiti?

(1) Highly unsatisfactory: Fewer than 25% of expected outcomes were achieved, including one or more very key immediate or intermediate outcomes, for no obvious reason (such as natural disasters).

(2) Unsatisfactory: 50% or less of expected outcomes were achieved, including one or more very key immediate or intermediate outcomes, for no obvious reason (such as natural disasters).

(3) Moderately unsatisfactory: More than 50% of expected immediate or intermediate outcomes were achieved, including the most key outcomes.

(4) Satisfactory: About 65% or more of expected outcomes were achieved, including the most key outcomes.

(5) Highly satisfactory: All or almost all expected immediate or intermediate outcomes were achieved, including the most key outcomes (80% or more).

Criterion/Question: 2.1.a To what extent do women, men, and children have better access to basic health and/or sanitation services? (Indicators 2.1.1 -2.1.2)

(1) Highly unsatisfactory: No change in the rate of use of health or sanitation services (m/w/g/b) in target areas, or no activity targeting this objective.

(2) Unsatisfactory: Little increase in the rate of use of health or sanitation services (m/w/g/b), but no ordinary cyclical changes, not directly related to CIDA efforts, or little activity targeting this objective.

(3) Moderately unsatisfactory: Moderate increase in the rate of use of health or sanitation services (m/w/g/b), directly related to CIDA efforts, but no more than 50% of targets achieved.

(4) Satisfactory: Increase in the rate of use of health or sanitation services (m/w/g/b), directly related to CIDA efforts, but below planned targets.

(5) Highly satisfactory: Increase in the rate of use of health or sanitation services (m/w/g/b), directly related to CIDA efforts, meeting or exceeding planned targets.

Criterion/Question: 2.1.b To what extent has health capacity been built? (Indicator 2.1.3)

(1) Highly unsatisfactory: No change in the capacity of target groups with regard to health services.

(2) Unsatisfactory: Little improvement in the capacity of target groups with regard to health services.

(3) Moderately unsatisfactory: Moderate improvement in the capacity of target groups with regard to health services.

(4) Satisfactory: Significant improvement in the capacity of target groups with regard to health services, but below planned targets.

(5) Highly satisfactory: Significant improvement in the capacity of target groups with regard to health services, meeting or exceeding planned targets.

Criterion/Question: 2.1.c To what extent did the project’s activities result in better coordination of Haitian and international partners in the health sector? (Indicator 2.1.4)

(1) Highly unsatisfactory: No evidence of efforts to improve coordination of Haitian or international stakeholders in the health sector.

(2) Unsatisfactory: Very little improvement in Haitian or international coordination of the health sector.

(3) Moderately unsatisfactory: Moderate improvement in Haitian or international coordination of the health sector (such as exchange of information).

(4) Satisfactory: Visible progress in the coordination of Haitian or international stakeholders, such as systems in place so the Government can better manage stakeholders in the health sector, but below planned targets.

(5) Highly satisfactory: Significant progress in the coordination of Haitian or international stakeholders, such as systems in place so the Government can better manage stakeholders in the health sector, meeting or exceeding planned targets.

Criterion/Question: 2.2 Did girls and boys in target areas improve their school access, retention, and completion rate? (Indicator 2.2.1)

(1) Highly unsatisfactory: No change in school access, retention, and completion rate (g/b) in target areas.

(2) Unsatisfactory: Little increase in school access, retention, and completion rate (g/b), but no ordinary cyclical changes, indirectly related to CIDA efforts.

(3) Moderately unsatisfactory: Moderate increase in school access, retention, and completion rate (g/b), directly related to CIDA efforts, but not more than 50% of targets achieved.

(4) Satisfactory: Increase in school access, retention, and completion rate (g/b), directly related to CIDA efforts, but below targets.

(5) Highly satisfactory: Increase in school access, retention, and completion rate (g/b), directly related to CIDA efforts, that meets or exceeds planned targets.

Criterion/Question: 2.3 To what extent were basic education systems of better quality; able to secure the future of children and youth; and consistent with gender equality principles? (Indicators 2.3.1, 2.3.2, 2.3.3)

(1) Highly unsatisfactory: Insufficient effort and no change in the quality of education; no evidence that education offers a better future for youth, or that it integrates gender equality principles.

(2) Unsatisfactory: Little increase in the quality of education, little evidence that education offers a better future for youth, and little effort to integrate gender equality principles.

(3) Moderately unsatisfactory: Evidence that the quality of education has substantially improved or is improving in target institutions, and efforts have been made to integrate gender equality principles, but with mixed success.

(4) Satisfactory: The quality of education has tangibly improved (based on established measurements of performance), and gender equality principles are well integrated and have yielded concrete results for women, men, girls, and boys.

(5) Highly satisfactory: General evidence, clearly related to CIDA, that the quality of education has improved at target institutions, and gender equality principles are well integrated, leading to significant progress in school access, retention, and completion rates.

Criterion/Question: 2.4 Have community engagement/mobilization strategies, used by education projects, improved the management of educational institutions? (Indicator 2.4.1)

(1) Highly unsatisfactory: There are serious problems in the design or execution of community engagement / mobilization strategies used by education projects, and no noticeable improvement in management of educational institutions.

(2) Unsatisfactory: Engagement / mobilization strategies have been designed and put in place, but have been ineffective, with only minor impacts on school management.

(3) Moderately unsatisfactory: Engagement / mobilization strategies have achieved mixed success in managing educational institutions.

(4) Satisfactory: Participation/mobilization strategies have led to several positive changes in managing educational institutions.

(5) Highly satisfactory: Participation/mobilization strategies have led to significant positive changes in managing a very large number of educational institutions.

Criterion/Question: 2.5 Are government institutions more effective, accountable, transparent, and able to ensure economic stability, as well as respect for human rights and gender equality principles? (Indicator 2.5.1)

(1) Highly unsatisfactory: Insufficient effort and no change in government capacity to use internationally accepted management methods.

(2) Unsatisfactory: Capacity-building strategies have been designed and put in place involving internationally accepted management methods, but are ineffective and have produced only a small increase in institutional capacity.

(3) Moderately unsatisfactory: A few positive institutional changes have resulted from capacity-building strategies involving internationally accepted management methods.

(4) Satisfactory: Several major institutional changes have resulted from capacity-building strategies involving internationally accepted management methods.

(5) Highly satisfactory: Major institutional changes have resulted from capacity-building strategies involving internationally accepted management methods.

Criterion/Question: 2.6 To what extent has capacity been built in strategic planning and implementation of government priorities at the various levels of government? (Indicator 2.6.1)

(1) Highly unsatisfactory: Insufficient effort and no change in government capacity strategic planning and implementation of priorities.

(2) Unsatisfactory: Capacity-building strategies have been designed and put in place, but are ineffective and have produced only small increases in government capacity.

(3) Moderately unsatisfactory: Capacity-building strategies have resulted in a few positive changes in the capacity of several levels of government for strategic planning and implementation of government priorities.

(4) Satisfactory: Capacity-building strategies have resulted in several positive changes in the capacity of several levels of government for strategic planning and implementation of government priorities.

(5) Highly satisfactory: Capacity-building strategies have resulted in significant positive changes in the capacity of several levels of government for strategic planning and implementation of government priorities.

Criterion/Question: 2.7.a Are citizens and civil society in a better position to take part in elections and democratic life, including better knowledge of their rights? (Indicator 2.7.1)

(1) Highly unsatisfactory: Insufficient effort and no change in the capacity of citizens and civil society to take part in elections and democratic life.

(2) Unsatisfactory: Some efforts have been made, but there has been no significant change in the capacity of citizens and civil society to take part in elections and democratic life.

(3) Moderately unsatisfactory: Efforts made have achieved some positive changes in the capacity of citizens and civil society to take part in elections and democratic life.

(4) Satisfactory: There is a clear link between CIDA efforts and capacity building of citizens and civil society to take part in elections and democratic life.

(5) Highly satisfactory: CIDA-funded projects show a clear link between their activities and the achievement of all or most expected outcomes relating to participation by citizens and civil society in elections and democratic life.

Criterion/Question: 2.7.b To what extent have there been changes in knowledge of rights among target groups, such as women and youth? (Indicator 2.7.2)

(1) Highly unsatisfactory: Insufficient effort and no change in knowledge of rights among target groups.

(2) Unsatisfactory: Some efforts have been made, but there has been no significant change in knowledge of rights among target groups.

(3) Moderately unsatisfactory: Efforts made have achieved some positive changes in knowledge of rights among target groups.

(4) Satisfactory: There is a clear link between CIDA efforts and better knowledge of rights among target groups.

(5) Highly satisfactory: CIDA-funded projects show a clear link between their activities and the achievement of all or most expected outcomes relating to better knowledge of rights among target groups.

Criterion/Question: 2.8 To what extent is the agricultural sector more productive and better protected against natural disasters, and has food security improved? (Indicator 2.8.1)

(1) Highly unsatisfactory: Insufficient effort and no evidence of increased agricultural productivity, resistance to natural disasters, or food security.

(2) Unsatisfactory: Some efforts have been made, but only minor changes have been achieved in increasing agricultural productivity, resistance to natural disasters, or food security.

(3) Moderately unsatisfactory: There is a clear link between CIDA efforts and a few positive changes in increasing agricultural productivity, resistance to natural disasters, or food security.

(4) Satisfactory: There is a clear link between CIDA efforts and significant changes in increasing agricultural productivity, resistance to natural disasters, or food security.

(5) Highly satisfactory: CIDA-funded projects show a clear link between their activities and the achievement of all or most expected outcomes related to increasing agricultural productivity, resistance to natural disasters, or food security.

Criterion/Question: 2.9 Do women and men have better access to technical and vocational training, microcredit and financial infrastructures? (Indicators 2.9.1 and 2.9.2)

(1) Highly unsatisfactory: No apparent change among women and men targeted by projects involving access to technical and vocational training, microcredit and financial infrastructures.

(2) Unsatisfactory: Project plans and activities have been implemented, but there has been no significant change among targeted women and men in the level of access to technical and vocational training, microcredit and financial infrastructures.

(3) Moderately unsatisfactory: Project plans and activities have been implemented, resulting in positive changes among targeted women and men in the level of access to technical and vocational training, microcredit and financial infrastructures.

(4) Satisfactory: Project plans and activities have been implemented, resulting in significant changes among targeted women and men in the level of access to technical and vocational training, microcredit and financial infrastructures.

(5) Highly satisfactory: Access to technical and vocational training, microcredit, and financial infrastructure targets have been achieved or almost achieved.

Criterion/Question: 2.10 To what extent has capacity been built in terms of agricultural production and management of local problems? (Indicator 2.10.1)

(1) Highly unsatisfactory: Insufficient effort and no change in terms of agricultural production capacity and management of local problems.

(2) Unsatisfactory: Some efforts have been made but there is no significant change in terms of agricultural production capacity and management of local problems.

(3) Moderately unsatisfactory: There is a clear link between CIDA efforts and some capacity building in terms of agricultural production capacity and management of local problems.

(4) Satisfactory: There is a clear link between CIDA efforts and capacity building in terms of agricultural production and management of local problems for most target groups.

(5) Highly satisfactory: CIDA-funded projects show a clear link between their activities and the achievement of all or most expected outcomes in terms of agricultural production capacity and management of local problems.

Criterion/Question: 2.11 Is there greater availability of a variety of food products grown in conditions that promote environmental sustainability? (Indicators 2.11.1 and 2.11.2)

(1) Highly unsatisfactory: No measures have been put in place to encourage greater availability of a variety of food products grown in conditions that promote environmental sustainability.

(2) Unsatisfactory: Some efforts have been made or some measures have been put in place, but there has been no clear, tangible benefit.

(3) Moderately unsatisfactory: There is a clear link between CIDA efforts and greater but moderate availability of a wider range of food products and sustainable methods of cultivation, and only for some target groups.

(4) Satisfactory: There is a clear link between CIDA efforts and satisfactory availability of a wider range of food products and sustainable methods of cultivation for most target groups.

(5) Highly satisfactory: There is widespread evidence of satisfactory availability of a wider range of food products and sustainable methods of cultivation for most or all target groups.

Criterion/Question: 2.12 Has CIDA put effective means in place to ensure the transition from humanitarian assistance to development? (Indicator 2.12.1)

(1) Highly unsatisfactory: No measures have been put in place to ensure the transition from humanitarian assistance to development.

(2) Unsatisfactory: Some efforts have been made or some measures have been put in place, but there has been no clear, tangible benefit.

(3) Moderately unsatisfactory: Several measures have been put in place, and there is some evidence of conditions appropriate to the transition from humanitarian assistance to development.

(4) Satisfactory: All planned means and measures have been put in place, and there is evidence of conditions favouring the transition from humanitarian assistance to development.

(5) Highly satisfactory: -

Criterion/Question: 2.13 Has CIDA put in place effective and flexible internal coordination mechanisms to manage the transition from humanitarian assistance and development? (Indicator 2.13.1)

(1) Highly unsatisfactory: There is no evidence of internal (even informal) coordination efforts among the various divisions.

(2) Unsatisfactory: Some internal coordination efforts have been made, but without any notable improvement in Canada’s response to needs in the field, or the efficiency or effectiveness of initiatives to manage the transition from humanitarian assistance to development.

(3) Moderately unsatisfactory: Internal coordination efforts have been made, and there are indications that this has somewhat improved Canada’s response to needs in the field, or the efficiency or effectiveness of initiatives to manage the transition from humanitarian assistance to development.

(4) Satisfactory: Internal coordination efforts have been made, and there are indications that this has significantly improved Canada’s response to needs in the field, or the efficiency or effectiveness of initiatives to manage the transition from humanitarian assistance to development (at least half of initiatives).

(5) Highly satisfactory: Internal coordination efforts have been made, and there are indications that this has very significantly improved Canada’s response to needs in the field, or the efficiency or effectiveness of initiatives to manage the transition from humanitarian assistance to development (at least three quarters of initiatives).

3. Sustainability

Criterion/Question: Q3. To what extent are benefits and results achieved likely to be maintained over the years?

(1) Highly unsatisfactory: There is very little likelihood that planned outcomes for the target group will continue after the end of the project, or that Haitian partners will own project activities.

(2) Unsatisfactory: For rehabilitation and reconstruction projects (post-humanitarian assistance), there is little likelihood that les rehabilitation or reconstruction activities will lead to development. There is little likelihood that planned outcomes for the target group will continue after the end of the project, or that Haitian partners will own project activities. For rehabilitation and reconstruction projects (post-humanitarian assistance), insufficient efforts are made to link the relief phase to rehabilitation, reconstruction and, ultimately, development.

(3) Moderately unsatisfactory: Some achieved results will be maintained, as long as Haitian partners own some project activities. For rehabilitation and reconstruction projects (post- humanitarian assistance), insufficient efforts are made to link the relief phase to rehabilitation, reconstruction and, ultimately, development.

(4) Satisfactory: It is likely that planned outcomes for the target group will continue after the end of the project, or that Haitian partners will own project activities. For rehabilitation and reconstruction projects (post- humanitarian assistance), credible efforts are made to link the relief phase to rehabilitation, reconstruction and, ultimately, development.

(5) Highly satisfactory: It is highly likely that planned outcomes for the target group will continue after the end of the project, or that Haitian partners will own project activities. For rehabilitation and reconstruction projects (post-humanitarian assistance), it is highly likely that rehabilitation or reconstruction activities will lead to development.

Criterion/Question: 3.1 Have CIDA-funded projects achieved technical and financial capacity building of Haitian partners, so they can own activities, or so recipients can continue after the project ends? (Indicators 3.1.1 and 3.2.1)

(1) Highly unsatisfactory: There is no evidence of efforts aimed at technical and financial capacity building of Haitian partners.

(2) Unsatisfactory: An unstructured or ineffective technical and financial capacity building approach achieves little short-term success.

(3) Moderately unsatisfactory: There is evidence of some technical and financial capacity building appropriate for the long-term survival of Haitian partners.

(4) Satisfactory: There has been technical and financial capacity building of Haitian partners, allowing them to become more self-sufficient.

(5) Highly satisfactory: There has been technical and financial capacity building of Haitian partners, and they can now fully own activities after the project ends.

4. Cross-cutting Themes

Criterion/Question: Q4. To what extent have CIDA-funded activities effectively addressed the cross-cutting theme of gender equality? (Indicator 4.1.1)

(1) Highly unsatisfactory: CIDA-funded activities are unlikely to contribute to gender equality or may actually widen the gender gap.

(2) Unsatisfactory: CIDA-funded activities lack gender equality objectives, or achieve less than a quarter of stated gender equality objectives. (Note: If a program or an activity clearly focuses on gender equality (such as maternal health programs), achieving more than half of stated objectives warrants a satisfactory score.

(3) Moderately unsatisfactory: CIDA-funded programs and projects achieve some stated gender equality objectives (less than 50%).

(4) Satisfactory: CIDA-funded programs and projects achieve most stated gender equality objectives (more than 50%).

(5) Highly satisfactory: CIDA-funded programs and projects achieve all or almost all stated gender equality objectives.

Criterion/Question: 4.1 To what extent have CIDA-funded activities effectively addressed the cross-cutting theme of the environment? (Indicator 4.1.2)

(1) Highly unsatisfactory: CIDA-funded activities do not include planned activities or criteria designed to favour environmental sustainability. Moreover, CIDA-funded programs and projects result in changes not in harmony with the environment.

(2) Unsatisfactory: CIDA-funded activities do not include planned activities or criteria designed to favour environmental sustainability. However, there is no direct indication that project or program results are not in harmony with the environment. OR CIDA has funded programs and projects that include planned activities or criteria designed to favour sustainable development, but they have not produced results.

(3) Moderately unsatisfactory: CIDA-funded activities include some activities to ensure environmental sustainability. These activities are successfully implemented, and results are in harmony with the environment.

(4) Satisfactory: CIDA-funded activities include activities to ensure environmental sustainability.

(5) Highly satisfactory: These activities are successfully implemented, and have yielded positive results. CIDA-funded activities are designed specifically to be in harmony with the environment, and achieved results have had significant impacts on the environment in targeted areas.

5. Coherence

Criterion/Question: Q5. To what extent were activities in Haiti coordinated with efforts by other donors and CIDA’s various delivery mechanisms?

(1) Highly unsatisfactory: CIDA has significantly different priorities from its partners, and lacks a credible strategy or plan to bridge the gap and/or to strengthen partnership over time.

(2) Unsatisfactory: CIDA has had significant difficulty in developing an effective relationship with partners, and there has been a significant gap between the priorities of CIDA and its partners.

(3) Moderately unsatisfactory: CIDA has had some difficulty in developing an effective relationship with partners, and there has been a degree of success in coordinating priorities between partners.

(4) Satisfactory: CIDA has improved the effectiveness of its relations with partners over time during the evaluation period, and this partnership was in effect at the time of the evaluation or has clearly been improved.

(5) Highly satisfactory: CIDA has consistently achieved a high level of partnership during the evaluation period.

Criterion/Question: 5.1 Have effective mechanisms been put in place to ensure whole-of-government coordination of the projects concerned? (Indicator 5.1.1)

(1) Highly unsatisfactory: There is no evidence that mechanisms have been put in place to ensure whole-of-government coordination of the projects concerned.

(2) Unsatisfactory: Mechanisms have been put in place to ensure whole-of-government coordination of the projects concerned, but have not resulted in any significant progress.

(3) Moderately unsatisfactory: Whole-of-government coordination mechanisms and stakeholders show some capacity to work together.

(4) Satisfactory: Whole-of-government coordination mechanisms have been put in place, and stakeholders work together to coordinate their activities, with some tangible benefits in the field.

(5) Highly satisfactory: Whole-of-government coordination mechanisms have been put in place, and all stakeholders are satisfied that they have built the capacity to communicate and work together, and have shown tangible benefits in the field.

Criterion/Question: 5.2. Have mechanisms been put in place to coordinate the various CIDA divisions active in Haiti? (Indicator 5.2.1)

(1) Highly unsatisfactory: There has been no clear effort to coordinate the various CIDA divisions active in Haiti.

(2) Unsatisfactory: CIDA efforts to create mechanisms, and to coordinate the various CIDA divisions active in Haiti, have not resulted in any significant progress.

(3) Moderately unsatisfactory: Coordination mechanisms have been put in place, and CIDA divisions active in Haiti show some capacity to work together.

(4) Satisfactory: Coordination mechanisms have been put in place, and CIDA divisions active in Haiti work together to coordinate their activities.

(5) Highly satisfactory: Coordination mechanisms have been put in place, and CIDA divisions active in Haiti are all satisfied with capacity building to communicate and work together.

Criterion/Question: 5.3 Has the use of NGOs been an effective means to achieve the priorities of the Canadian cooperation Program with Haiti? (Indicator 5.3.1)

(1) Highly unsatisfactory: There is no evidence that the work of NGOs has contributed value or effectiveness to the Canadian cooperation Program.

(2) Unsatisfactory: NGOs have contributed some value and effectiveness, but by substituting for government responsibilities, without any coordination with government stakeholders, or any compliance with Haitian policies and regulations.

(3) Moderately unsatisfactory: NGOs have contributed limited value and effectiveness by substituting for government responsibilities, with few coordination efforts with government stakeholders, and limited efforts to comply with Haitian policies and regulations.

(4) Satisfactory: NGOs have contributed value and effectiveness by supporting government responsibilities involving a good level of coordination with government stakeholders, and compliance with Haitian policies and regulations.

(5) Highly satisfactory: NGOs have contributed clear value and effectiveness by supporting government responsibilities involving high levels of coordination with government stakeholders, and a high level of compliance with Haitian policies and regulations.

6. Aid Effectiveness

Criterion/Question: Q6. How has the Haiti program generally performed in relation to the principles of the Paris Declaration (that is, ownership, textment, and harmonization)?

(1) Highly unsatisfactory: The Haiti program made no effort to implement aid effectiveness principles.

(2) Unsatisfactory: The Haiti program made some efforts to implement aid effectiveness principles, but these efforts were not enough to achieve tangible results.

(3) Moderately unsatisfactory: The Haiti program made significant efforts to implement aid effectiveness principles, with some success in ownership, textment, and harmonization.

(4) Satisfactory: The Haiti program made significant efforts to implement aid effectiveness principles, leading to progress on one of the principles of the Paris Declaration (ownership, textment, or harmonization).

(5) Highly satisfactory: The Haiti program made considerable and sustained efforts to implement aid effectiveness principles, leading to a fundamental change in ownership, textment, and harmonization.

Criterion/Question: 6.1. What measures were put in place to enable the Government of Haiti to play its role in coordinating international cooperation? (Indicator 6.1.1)